Emotional dysregulation is a hallmark feature of borderline personality disorder (BPD) and eating disorders (ED), which impacts the individuals’ well-being and functioning. Oxytocin dysregulation has been involved in social cognition deficits associated with these disorders.

MethodsWe conducted a study including a total 108 women categorized into 3 groups: 50 with eating disorders (ED), 35 with borderline personality disorder (BPD), and 23 healthy controls. Psychopathological profiles were assessed using the Bulimic Investigatory Test Edinburgh (BITE), the Eating Attitude Test 40 (EAT-40), the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11), and the Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire (RSQ). Plasma oxytocin levels and oxytocin receptor expression were measured as well.

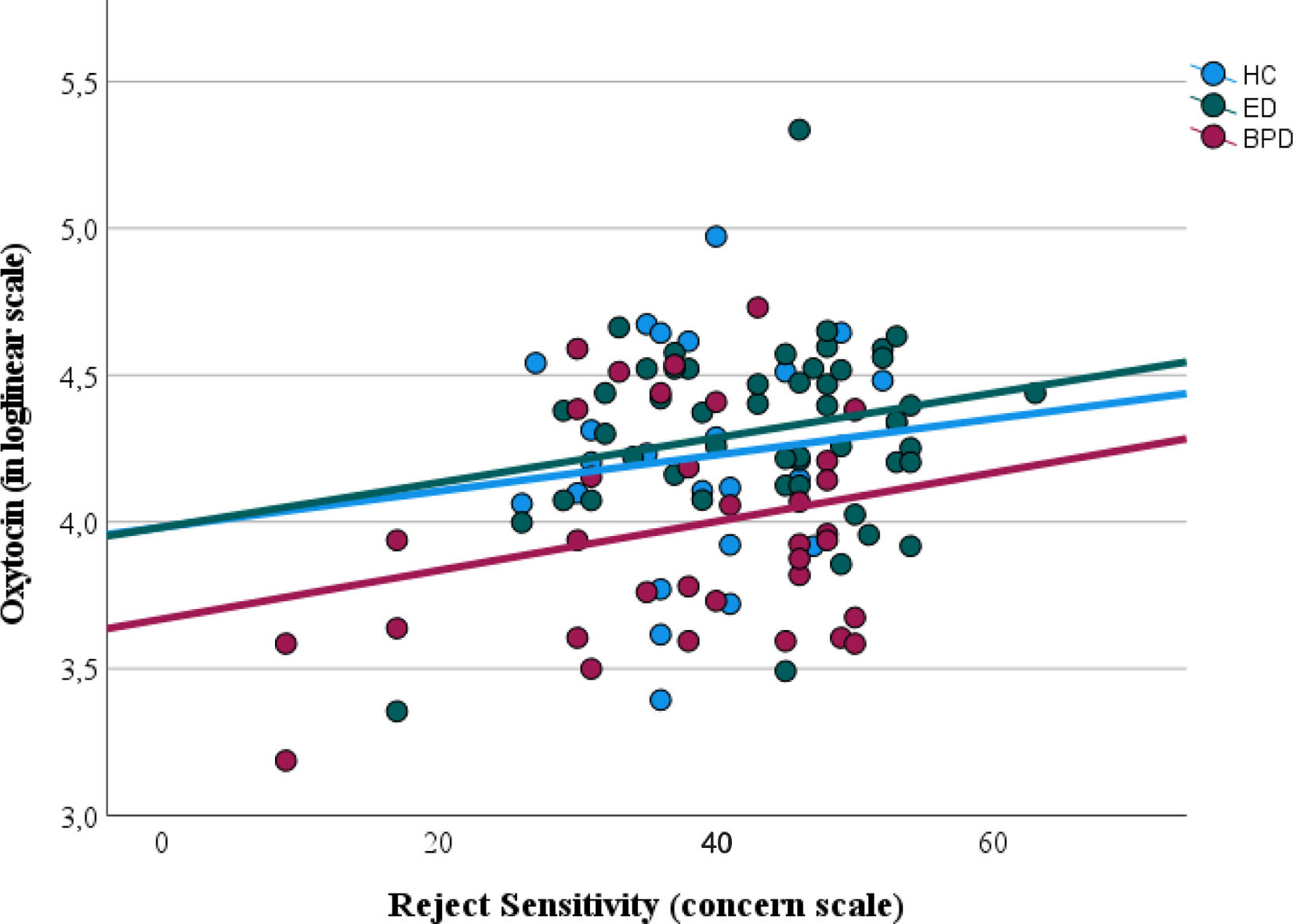

ResultsBPD patients exhibited significantly lower plasma oxytocin levels vs ED patients and healthy controls. However, oxytocin receptor expression did not differ significantly across the groups. Oxytocin levels were positively associated with rejection sensitivity, particularly in BPD patients.

ConclusionsOur findings suggest a potential role of oxytocin dysregulation in emotional dysregulation and rejection sensitivity, particularly in BPD. Higher oxytocin levels in ED patients may serve as a compensatory mechanism to mitigate challenges in interpersonal relationships. These results highlight the importance of personalized therapeutic interventions targeting oxytocin dysregulation in the management of ED and BPD.

Emotional dysregulation is a prevalent feature of various mental disorders, marked by intense mood swings including unstable relationships, heightened rejection sensitivity, impulsive behavior and challenges in emotional control. This condition carries serious health consequences and imposes a considerable economic burden due to its enduring impact and, in some cases, chronic nature.1

Emotional dysregulation characterizes borderline personality disorders (BPD) and eating disorders (ED) which may share some common pathophysiological underpinnings and syndromic features including negative affect, poor self-esteem, impulse dysregulation, interpersonal or rejection sensitivity, and social cognitive deficits.2–4 The lifetime prevalence rate of these disorders is moderately high in Europe with an estimated prevalence of 3% for BPD, <1–4% for anorexia nervosa (AN), <1–2 for bulimia nervosa (BN) and 1–4% for binge eating disorders (BED). Furthermore, these disorders may be associated with clinical management complexity and higher drop-out rates leading to poorer prognosis.5 Severity, a characteristic inherent to these disorders, impairs both quality of life and interpersonal relations, while also increasing the number of productive years lost to disability.6 Disability and long-term progression seem to be associated with higher interpersonal dysfunctions that remain even after impulsive behavior remission, leading to interpersonal rejection and empathy dysfunction.7

Rejection sensitivity (RS) has been associated with emotional dysregulation. A considerable amount of literature has been published on empathy and RS in BPD. RS is defined as ‘the disposition to anxiously expect, readily perceive and intensely react torejection’.8 There is empirical evidence stressing that RS has a great impact on interpersonal relationships (e.g., through a negative or hostile attitude toward the counterpart) and on intrapersonal functioning (e.g., greater difficulty detaching from distressing thoughts and emotions). Some studies have found high correlations between the RS and borderline-specific cognitions, such as effortful control and intolerance of ambiguity assuming that oversensitivity to social rejection is an important feature of BPD.9,10 It has been also demonstrated that RS significantly mediates the relationship between BPD symptoms and disordered eating.11 However, while little is known about the connection between RS and ED, a study by Cardi et al. from 2013 looked into social reward and RS in individuals with ED revealing a similar vigilance to rejection and avoidance of social reward.12 Furthermore, recent evidence suggests that RS may play a role in the maintenance or worsening of ED disease.13

Research examining the links between psychiatric signs and neurobiological profiles has proliferated over the past decade, which has led to a growing interest in oxytocin as a potential modulator of these disorders with emotional dysregulation.14 Oxytocin is a neuropeptide and hormone that plays a key role in inducing uterine contraction during parturition and milk let-down during lactation.15 Furthermore, it is commonly associated with interpersonal relationships and social cognition through its involvement in trust processes, positive social appraisal, pro-social behavior and anxiety.16 It is also a key regulator of energy balance through its effects on eating behavior and metabolism.17,18 Recently, there has been a growing interest in the role of intranasal oxytocin in social-emotional processing as it may acutely induce behavioral changes.19 The putative role of dysregulated oxytocin function may be a potential contributing factor to social cognition impairment and RS.20 Prior research findings on intranasal oxytocin administration suggest that hormone administration may increase accuracy in emotion recognition, and enhance the expression of positive emotions, social memory, adaptive emotion regulation and interpersonal trust.21 In ED, oxytocin secretion may be dysregulated. However, its possible connection to social cognition impairment or RS is not yet fully understood. Low basal serum levels of oxytocin have been reported in women with AN despite its known anorexigenic effect. However, these results seem to be associated with social–emotional dysfunction.22,23 Indeed, postprandial oxytocin concentrations are associated with ED psychopathology.24 Postprandial oxytocin levels were found to be elevated in women with AN, speculating that its anxiolytic effect may reduce the stress and anxiety associated with meal consumption.25 Anomalies in oxytocin functioning might also explain mechanisms underlying BN or BED due to its role in palatable food intake.26 On the other hand, BPD may also be related to dysregulations in the oxytocin system as it is a strong modulator of socio-emotional functioning (e.g., hypersensitivity for social threats, reduced trust, or hypermentalizing).27 Several studies investigating oxytocin have been conducted in BPD showing that not only oxytocin levels are lower28 but also the oxytocin receptor (OTR) expression.29 However, the effects of oxytocin on BPD patients’ social cognition and behavior may be strongly influenced by early life experiences, which are known to have profound and lasting effects on interpersonal security and attachment, possibly modulated by the oxytocinergic system.30 Indeed, some studies have indicated that lower levels of oxytocin are associated with a past medical history of childhood trauma, while others have suggested a connection between oxytocin and impulsivity. There is a dose-dependent inverse relationship between the severity of childhood trauma experiences and oxytocin concentration, with emotional abuse and neglect showing the strongest associations among them.31 These findings from various studies propose a link between oxytocin and impulsivity, with individuals exhibiting higher impulsivity scores having lower serum oxytocin levels.32

Furthermore, ED co-occurring with BPD is a relatively common finding. The presence of both disorders is a strong marker of severity and a flag for poor treatment adherence and prognosis.33 Additionally, this co-occurrence also confers transdiagnostic risk for self-harm and suicidal behavior.34 Therefore, there are strong transdiagnostic elements between BPD and ED including neurobiological aspects and syndromal components2 which may constitute an endophenotype of emotional dysregulation disorders.

The aim of the current study is to determine oxytocin plasma levels and the expression of the oxytocin receptor in a sample of patients with an ED and BPD. We expect that these patients would show an altered oxytocin function related to emotional dysregulation and RS vs healthy controls. Furthermore, we will focus on its potential association with clinical features including impulsivity or trauma history.

Materials and methodsSample and assessment toolsData for the present study were collected between 2017 and 2019. Participants were consecutively recruited from 3 participant hospitals in Spain (Hospital Universitario ClínicoSan Carlos, Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla and Hospital General de Ciudad Real).

The sample included a total of 108 women. Patients from 2 diagnostic groups were considered: 50 patients with an ED (m, 26.58 years; SD 6.32) 52% of whom were of the restrictive subtype (ED-R) and 48% of the binge-eating/purging subtype (ED-P); and 35 patients with BPD (m, 30.51; SD 10.00); and a control group including 23 healthy subjects (m, 23.35; SD 2.53). The diagnosis of both disorders was established using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV text revised (DSM-IV-TR).35 Moreover, a signed informed consent form was provided by each participant. The inclusion criteria for the study were being older than 18 years and having been diagnosed with either BPD or ED based on DSM-V as confirmed by a senior psychiatrist. Exclusion criteria for the case group included the co-occurrence of BPD and ED, comorbidity with schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder or other affective disorders, chronic organic diseases and intellectual disability. Control women were free from any mental disorder, as ascertained after the delivery of the clinical interview by a senior psychiatrist. All the protocols delivered in this study were approved by an Ethics Committee from each recruiting center.

The patients’ psychopathological profile was rated with the following instruments: the Bulimic Investigatory Test Edinburgh (BITE),36 the Eating Attitude Test 40 (EAT-40),37 the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11)38 and the Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire (RSQ).39 RSQ measures 2 dimensions: (1) degree of anxiety and concern on the outcome and (2) expectations of acceptance or rejection. Respondents are asked about their expectations of rejection in hypothetical situations in which it is possible that an important acquaintance or a significant other refuses their request for help, advice or companionship. People who are highly sensitive to rejection expect rejection and are also concerned about the outcome in various interpersonal situations.9 The Trauma Questionnaire (TQ) was used to evaluate trauma events and school bullying episodes.40

Blood sample, specimen collection and preparationA venous blood sample (10mL) was collected into heparinized tubes from each participant between 8:00 and 10:00h after fasting overnight. Plasma was obtained from a blood sample by centrifuging it at 1800rpm for 10min at 4̊C immediately after sample collection. The resultant plasma sample was stored at −80̊C. The rest of the sample was 1:2 diluted in a culture medium (RPMI 1640, Lonza, Verviers, Belgium) and a gradient with Ficoll-Paque® (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) was used to isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) by centrifugation (800g×40min, room temperature – RT–). The PBMC layer was aspired and suspended in RPMI and centrifuged (1116g×10min, RT). Supernatant was removed and mononuclear cell-enriched pellet stored at −80̊C.

Biochemical determination of oxytocin and oxytocin receptorOxytocin plasma levels were measured through a commercially competitive ELISA-based kit (ref. 500440, Cayman Chemical, Estonia) following the manufacturer's instructions for use. The intra- and inter-assay CV were 7.2% and 7.0%, respectively. To obtain valid assay results, plasma samples were previously purified using C18 Sep-Pak columns (Waters, United Kingdom) to remove any molecules that could interfere with the assay.41

The cytosolic fraction was extracted from PBMCs as described in previous publications.29 Oxytocin receptor (OTR) levels were determined in PBMC cytosolic extracts via Western blot. Protein concentration was quantified and adjusted using the Bradford method. A total of 15μg of cytosolic extracts were loaded onto an electrophoresis gel and separated by molecular weight. Proteins were then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Transfer Pack, Bio-Rad) using a semi-dry transfer system (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked with 5% BSA for 1.5h and subsequently incubated overnight at 4̊C with primary antibodies against OTR (1:750 in 0.5% BSA, sc-515809, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and β-actin (1:15000, A5441, Sigma–Aldrich). Following washes with TBS-Tween, membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 90min at room temperature. Immunoreactivity was visualized using an ECL kit (Amersham Ibérica, Spain) according to the manufacturer's instructions for use. Blots were imaged using an Odyssey Fc System (Li-COR Biosciences, Germany) and quantified densitometrically using NIH ImageJ software. β-Actin served as the loading control and experiments were performed in triplicate.

Statistical analysisData are expressed as mean±standard deviation for quantitative variables, and proportion of cases for categorical variables. Sociodemographic and clinical factors were compared across 3 study groups (ED, BPD and controls) by means of analysis of variance (ANOVA). Bonferroni or Tamhane test (in case of homocedasticity assumption being violated) were conducted for multiple comparisons. The η2partial was used as an effect size estimate. Multivariate linear regression analysis was then run to study the relationship between each dependent variable (oxytocin levels and OTR, under loglinear scale), and sociodemographic and clinical factors (BIS-11 total, TQ y RSQ-concern), controlling for the clinical group. The body mass index was used as a weighting variable due to its potential relationship with other covariates (e.g., reject sensitivity; r=−.24; p<.05). Therefore, an increasing covariate entry strategy was followed, firstly considering a model covering sociodemographic covariates (e.g., age and clinical group) and, then, adding clinical covariates (BIS-11 and TQ total scores, and RSQ-concern score). A model would significantly explain the outcome, when the related analysis of variance statistic was significant. The adjusted R2 was used as an effect size estimator. The odds ratio (OR) was used as an estimate of the size of the relationship with the outcome.

All analyses were conducted using the IBM SPSS v.25 and R software (packages paran, psych).

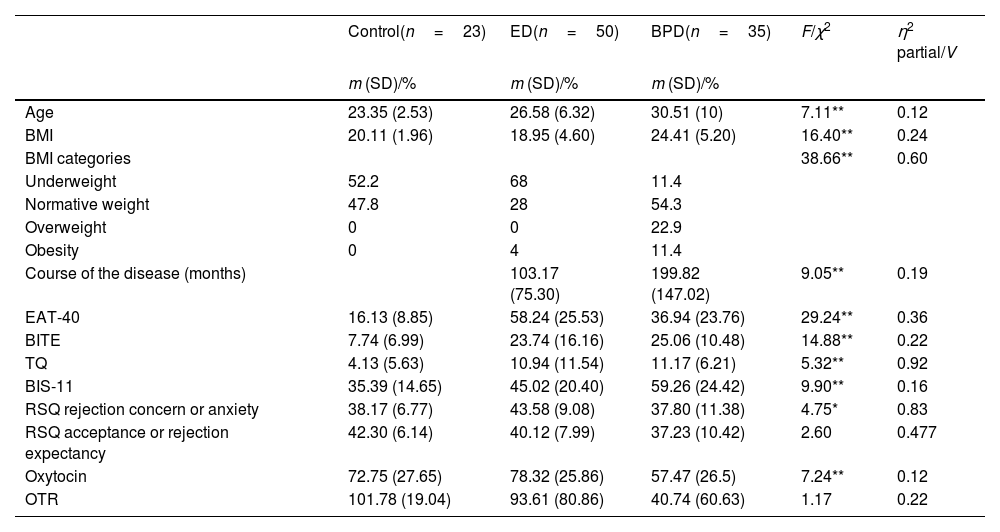

ResultsTable 1 illustrates the relevant characteristics of the sample and the clinical rating scales. Patients were older than controls and there was a significant difference in the BMI across the groups, being lower in the ED as expected (p<.05). Additionally, a higher proportion of BPD patients with overweight and obesity conditions were observed. The duration of illness was significantly different between the patient groups with a greater duration in BPD patients. In all the clinical rating scales, patients scored significantly higher than controls with the BPD group showing higher levels of eating-related symptoms vs controls in the EAT-40 and BITE scales but scoring lower than the ED group in the EAT40. In the BITE scale, BPD scored lower than the ED-P but higher than the ED-R. Regarding trauma experience, patients from the ED-P group showed the highest scores on the TQ followed by BPD and ED-R, however when comparing both the ED and BPD groups, the latter scored higher on the trauma scale. As expected by diagnostic criteria, BPD obtained a higher impulsivity score on the BIS-11 followed by ED-P and ED-R. In terms of the RSQ domains, we found that rejection concerns were similar in all subjects, with significantly higher scores in ED but lower scores in BPD.

Relevant characteristics of the study participants and clinical rating scales.

| Control(n=23) | ED(n=50) | BPD(n=35) | F/χ2 | η2 partial/V | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m (SD)/% | m (SD)/% | m (SD)/% | |||

| Age | 23.35 (2.53) | 26.58 (6.32) | 30.51 (10) | 7.11** | 0.12 |

| BMI | 20.11 (1.96) | 18.95 (4.60) | 24.41 (5.20) | 16.40** | 0.24 |

| BMI categories | 38.66** | 0.60 | |||

| Underweight | 52.2 | 68 | 11.4 | ||

| Normative weight | 47.8 | 28 | 54.3 | ||

| Overweight | 0 | 0 | 22.9 | ||

| Obesity | 0 | 4 | 11.4 | ||

| Course of the disease (months) | 103.17 (75.30) | 199.82 (147.02) | 9.05** | 0.19 | |

| EAT-40 | 16.13 (8.85) | 58.24 (25.53) | 36.94 (23.76) | 29.24** | 0.36 |

| BITE | 7.74 (6.99) | 23.74 (16.16) | 25.06 (10.48) | 14.88** | 0.22 |

| TQ | 4.13 (5.63) | 10.94 (11.54) | 11.17 (6.21) | 5.32** | 0.92 |

| BIS-11 | 35.39 (14.65) | 45.02 (20.40) | 59.26 (24.42) | 9.90** | 0.16 |

| RSQ rejection concern or anxiety | 38.17 (6.77) | 43.58 (9.08) | 37.80 (11.38) | 4.75* | 0.83 |

| RSQ acceptance or rejection expectancy | 42.30 (6.14) | 40.12 (7.99) | 37.23 (10.42) | 2.60 | 0.477 |

| Oxytocin | 72.75 (27.65) | 78.32 (25.86) | 57.47 (26.5) | 7.24** | 0.12 |

| OTR | 101.78 (19.04) | 93.61 (80.86) | 40.74 (60.63) | 1.17 | 0.22 |

Note. Mean and standard deviation were provided for continuous variables, as well as the F-based test statistic and η2 partial square as an effect size estimate.

Proportion of cases, Chi-square test statistic (with Fisher's exact test correction for the p value) and Cramer's V (effect size estimate) were provided for the BMI categories variable, due to its ordinal nature.

BMI: body mass index; EAT-40: Eating Attitude Test 40; BITE: Bulimic Investigatory Test Edinburgh; TQ: Trauma Questionnaire; BIS-11: Barratt Impulsiveness Scale 11; RSQ: Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire; OTR: oxytocin receptor.

Regarding oxytocin outcomes (e.g., circulation oxytocin levels, and OT receptor), women diagnosed with an BPD had significantly lower plasma levels of oxytocin vs healthy controls and ED patients (p<.05). However, there were no significant inter-group differences in the oxytocin receptor expression (see Table 1).

Finally, the multivariate regression model revealed that the model with all the covariates (sociodemographic and clinical) significantly explained the levels of oxytocin, F (5, 102)=4.07, p<.01. This model showed an adjusted R2=.13. We found 2 significant covariates within this model: the clinical group (OR, 0.89, 95%CI, 0.82, 0.97; t, −2.85, p<.05), as expected by results from the previous analysis; and the RS, concern scale (OR, 1.09, 95%CI, 1.02, 1.18; t, 2.46, p<.05). Fig. 1 illustrates the relationship between oxytocin levels (in loglinear scale) and the concern domain of the RS showing that circulating oxytocin increases with increasing RS concern. No other covariates were significant in this model. The model to explain oxytocin receptor expression was not significant, F (5, 102)=1.92, p=.10, which supports that none of the covariates in analysis was significantly associated with oxytocin receptor expression.

DiscussionFormer studies have provided evidence on the role of oxytocin in the pathophysiology of social cognition and empathy related to emotional dysregulation.16,42 ED and BPD are both particularly associated with RS and poor social cognition performance, probably due to negative experiences, such as trauma.9,12

When discussing the clinical results of RS in patients with ED and BPD and their relationship with impulsivity and trauma, several noteworthy findings emerge from this study. Firstly, patients with ED exhibited significantly higher RS vs those with BPD, particularly regarding rejection concerns, which suggests that individuals with ED may be more sensitive to rejection, potentially influencing their treatment approach and therapeutic interventions.

Moreover, regarding impulsivity, BPD patients demonstrated the highest impulsivity scores, followed by those with ED-P and ED-R, which is consistent with diagnostic criteria expectations, indicating the importance of addressing impulsivity in the treatment of BPD and certain subtypes of ED.43,2

Regarding trauma experience, although patients with ED-P displayed the highest scores on the trauma scale followed by BPD and ED-R, when comparing ED and BPD groups directly, BPD patients scored higher, which underscores the significance of trauma-informed care in the management of BPD and ED, highlighting the need for tailored therapeutic approaches to address trauma-related symptoms.44

In line with the relevant results reported in the literature, we sought to explore whether both disorders might exhibit a deviated oxytocin function and any potential association with clinical severity factors (e.g., trauma, RS, and impulsivity). Our study supports previous findings indicating a dysfunctional oxytocin system among patients with an ED or BPD,25,28,29 demonstrating decreased serum levels of oxytocin in BPD compared with the other groups. Nonetheless, OTR expression was not impaired. There was a tendency in the ED-R for oxytocin to exhibit higher plasma levels than the other groups, including the ED-P. These levels seem to be more closely aligned with those found in BPD, which could potentially explain the lack of appetite in these patients because of the anorexigenic effects of oxytocin.45

Contrary to expectations, another significant finding was that oxytocin secretion was positively associated with increased RS in terms of concern or anxiety. It is, indeed, known that oxytocin improves the positive effect of social support on stress reactions and, in these circumstances, exerts anxiolytic effects.17,25 Therefore, the presence of higher levels of oxytocin in patients with higher scores in RS could be an attempt to regulate the emotional or social dysfunction, reduce the degree of anxiety, and improve social attachment. Although oxytocin does not invariably facilitate prosocial behavior it may produce protective or even defensive–aggressive responses revealing its vulnerability to context dependent factors.46 The effects of oxytocin are highly context-dependent. In stressful or negative social contexts, oxytocin can increase social vigilance and promote avoidance behaviors, mediated by specific neural circuits, such as the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, which are activated in response to social stress.47,48 Additionally, oxytocin enhances the salience of both positive and negative social cues. As a result, in situations where social rejection is perceived, it may amplify emotional responses to negative cues, leading to increased RS,49,50 which is another factor influencing the effects of oxytocin is individual variability, particularly attachment style. For individuals with high attachment anxiety, oxytocin can exacerbate interpersonal insecurities and increase RS.51 This is so because oxytocin increases attention to social threats and negative social interactions, making these individuals more reactive in social situations.52 This argument is quite in line with novel therapies, such as temperament-based treatments that are associated with an updated mechanistic understanding of these disorders.53 This study underscores the importance of recognizing that addressing the challenges and interpersonal hypersensitivity experienced by patients with ED should be a primary focus of both psychotherapeutic interventions and pharmacological treatment.54

On the other hand, several limitations in this study need to be considered. First, this study follows a cross-sectional design. As a result, reverse causation hypothesis could not be tested in this study. Besides, the sample size is modest. Nonetheless, our study includes more patients than most of the articles published to date. We also acknowledge that the inclusion of only female participants limits the applicability of results to men or mixed-gender populations. Another limitation is that this study measures peripheral oxytocin levels, which may not represent oxytocin concentrations in relevant brain regions.24 Further, there was no quantification of other neuropeptides, such as vasopressin, which may synergistically work with oxytocin in social cognition processes.18 As a matter of fact, the possible influence of drugs for patients in the neurochemical results were not considered.

Considering that both ED and BPD share emotional dysregulation, our study provides evidence on its biological implications. First, regarding BPD, there is a lower of anxiety or concern about the outcome in terms of RS, likely connected with lower levels of oxytocin. Therefore, it could be proposed that individuals with BPD, conscious of their challenges in interpersonal relationships potentially linked to reduced oxytocin levels, exhibit lower RS vs those with EDs, given their limited exposure to intimate relationships and tendency toward impulsive and unstable bonds.55 As mentioned above, oxytocin may also have divergent effects (e.g., protective or defensive-aggressive responses) depending on contextual factors,56 as might be the case with RS.

On the other hand, in patients with ED, elevated oxytocin levels may contribute to the anorexigenic effects of food intake, while also potentially enabling them to mitigate their heightened RS (as indicated by scores on the RSQ) in interpersonal relationships, thereby facilitating delicate social interactions among these individuals.57

In this eating-related context, higher levels of oxytocin may be necessary to compensate for this stressful exposure through its known anxiolytic effects.16 It is, therefore, important to emphasize the transdiagnostic role of the RS, which is higher in patients with an ED and lower in those with BPD, and its association with oxytocin levels. Further research should be conducted to investigate comorbid ED and BPD patients to evaluate their oxytocin levels.

The evidence from this study suggests that oxytocin levels seem to be different among impulsive disorders, such as BPD and ED vs healthy controls. Oxytocin levels are lowered in patients with BPD and high in ED aligning with heightened RS, interpersonal relationship challenges, and emotional regulation of intake. However, further work needs to be done to establish this relationship. Currently, it seems that the main difference between both ED and BPD is the mechanism they use to regulate emotions, that is, by means of eating behaviors and dysfunctional bounding respectively. Moreover, this study has therapeutic implications for further personalizing oxytocin treatment based on diagnosis and context-dependent factors, such as RS.

FundingThis work was supported by the PI20/01471 and PI16/01949 projects, integrated in the Plan National de I + D + I, AES 20–23 and 16–19 respectively; funded by the ISCIII and co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). “A way to make Europe”.

None declared.

None declared.