Approximately 20–30% of patients with schizophrenia fail to respond to antipsychotic treatment and are considered treatment resistant (TR). Although clozapine is the treatment of choice in these patients, in real-world clinical settings, clinicians often delay clozapine initiation, especially in first-episode psychosis (FEP).

AimThe main aim of this study was to describe prescription patterns for clozapine in a sample of patients diagnosed with FEP and receiving specialized treatment at a university hospital. More specifically, we aimed to determine the following: (1) the proportion of patients who received clozapine within two years of disease onset, (2) baseline predictors of clozapine use, (3) time from starting the first antipsychotic to clozapine initiation, (4) concomitant medications, and (5) clozapine-related adverse effects.

MethodsAll patients admitted to a specialized FEP treatment unit at our hospital between April 2013 and July 2020 were included and followed for two years. The following variables were assessed: baseline sociodemographic characteristics; medications prescribed during follow-up; clozapine-related adverse effects; and baseline predictors of clozapine use. We classified the sample into three groups: clozapine users, clozapine-eligible, and non-treatment resistant (TR).

ResultsA total of 255 patients were consecutively included. Of these, 20 (7.8%) received clozapine, 57 (22.4%) were clozapine-eligible, and 178 (69.8%) were non-TR. The only significant variable associated with clozapine use at baseline was the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score (R2=0.09, B=−0.07; OR=0.94; 95% CI: 0.88–0.99; p=0.019). The median time to clozapine initiation was 55.0 (93.3) days. The most common side effect was sedation.

ConclusionsA significant proportion (30.2%) of patients in this cohort were treatment resistant and eligible for clozapine. However, only 7.8% of the sample received clozapine, indicating that this medication was underprescribed. A lower baseline GAF score was associated with clozapine use within two years, suggesting that it could be used to facilitate the early identification of patients who will need treatment with clozapine, which could in turn improve treatment outcomes.

Approximately half of all patients with first-episode psychosis (FEP) achieve symptomatic remission.1 However, a substantial proportion of these patients (20–30%) fail to respond to treatment and become treatment resistant,2 which has been defined by the Treatment Response and Resistance in Psychosis Group as the failure to respond to at least two different antipsychotic adequate trials, prescribed during an appropriate time and within a correct dose.3

In patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia (TRS), the treatment of choice is clozapine.4 This drug has been shown to achieve superior clinical outcomes in patients with schizophrenia and TRS.5 Clozapine has several advantages over other antipsychotics, including lower all-cause mortality,6,7 a lower suicide and self-harm rate, less re-hospitalization, a lower risk of relapse,8 and a decreased risk of substance abuse relapse.9 However, due to legal requirements and to potentially severe adverse effects, including agranulocytosis and myocarditis (both of which may be fatal), increased risk of metabolic syndrome, intestinal obstruction, diabetic ketoacidosis, and convulsions, among other effects, clozapine is generally not used as a first-line treatment. Nevertheless, most of these adverse effects can be successfully managed without discontinuing treatment.10 In addition, there is growing evidence of the possible benefit of early use of clozapine in some patients.11,12

Despite the well-documented benefits of clozapine in TRS, this drug remains underutilized in real-world clinical practice, although prescription rates vary highly depending on the specific country and/or region.13 The clozapine prescription rate in the United States (U.S.) is estimated to be around 2–3%.14 However, only a few U.S. states, reported prescription rates greater than 10%.15 In Europe, the prescription rate is also highly variable, with an estimated rate of 10.2% in Denmark, 13.7% in England and Wales, and 18.6% in some regions of Spain.16

In routine clinical practice, clinicians often delay initiation of clozapine, especially in FEP patients.17 In two studies performed to evaluate adherence to clinical guidelines in antipsychotic therapy,17,18 the estimated theoretical delay in clozapine initiation ranged from 19.3 weeks to 5.5 years. Those studies found that clinicians, rather than initiate clozapine, tended to increase the antipsychotic dose, prescribe additional medications (i.e., polypharmacy), or perform additional antipsychotic trials (from three to five different antipsychotics). In this regard, it is important to note that the available data show that delaying the switch to clozapine could worsen the clinical course of schizophrenia.19,20 According to current recommendations, patients should receive two different antipsychotics before switching to clozapine.12,20 Although some studies 21,22 have described predictors of non-response in first episode psychosis patients, more information enabling to predict which patients are most likely to develop treatment resistance at illness onset is still needed; the ability to do so would be highly beneficial, as it would allow us to improve clinical outcomes while also avoiding ineffective treatments during this critical period. Moreover, this information could be especially relevant in patients with poorer clinical outcomes such as patients with early onset schizophrenia.

Some studies have been performed to evaluate clozapine prescription patterns in FEP samples, including doses, side effects, prior antipsychotics, and adjunctive treatments.23–27 However, more detailed and comprehensive information is still needed, as previous studies presented non-exhaustive information regarding this topic. Furthermore, it is not rare to find hesitancies among professionals and patients when starting clozapine that can be explained—at least in part—by the lack of more detailed information. In this context, there is a clear need to better characterize real-world prescription patterns for clozapine in patients with FEP, which would provide clinicians with a better understanding of the risks and benefits of clozapine. This could potentially encourage clinicians to more closely adhere to clinical guidelines. In addition, a better understanding of the adverse effects associated with clozapine use could improve their clinical management.

In this context, the main aim of the present study was to describe prescription patterns for clozapine use in a real-world sample of FEP patients treated at our hospital.

More specifically, we sought to determine the following: (1) clozapine prescription rates in our sample; (2) time from the first antipsychotic to clozapine initiation; (3) type, number, and dose of antipsychotics prescribed before clozapine; (4) adverse events and reasons of clozapine discontinuation; (5) concomitant psychiatric treatments in clozapine users; (6) differences in clinical and sociodemographic factors at baseline between clozapine users, clozapine-eligible patients and non-TR patients; (7) clinical and sociodemographic factors at baseline associated with clozapine treatment at two years; (8) differences in functionality between clozapine users and clozapine-eligible patients at two years follow-up.

MethodsStudy populationThe study sample comprised patients diagnosed with FEP between April 2013 and July 2020. All participants were treated at the Study and Treatment Program for FEP (ETEP) at the Hospital del Mar in Barcelona, Spain. The ETEP program is a specialized early intervention service created in 2008 for young adults (age 18–35) diagnosed with FEP. The program consists of a multimodal intervention that includes a comprehensive clinical assessment and intensive medical and psychosocial treatment in accordance with national and international guidelines. A detailed description of the ETEP program is provided in the study by Toll et al.28

Inclusion/exclusion criteriaThe study inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) age 18–35; (b) first contact with the ETEP program; (c) DSM-V criteria for brief psychotic disorder, schizophreniform disorder, schizophrenia (<1 year of symptoms), schizoaffective disorder, or unspecified psychosis; (d) no previous history of a severe neurologic medical condition or severe traumatic brain injury; (e) presumed IQ (based on clinical records)>80; (f) no substance abuse or dependence disorder, except for cannabis or nicotine use.

Study designA comprehensive assessment was performed at baseline by two experienced psychiatrists (A.M. and D.B.). This assessment included the following: registration of sociodemographic variables (age, sex, living situation, marital status); and assessment of substance use, including tobacco (users vs. nonusers and percentage of heavy tobacco smoking) and cannabis use (joints per week after dichotomization into users/nonusers), and administration of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-V. We defined heavy smoking as tobacco use≥30 cigarettes per day. In addition, the following scales were administered: the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for symptoms related to psychosis29; the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) for functionality30; the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS) for depressive symptoms31; and the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) for mania symptoms.32 All patients were followed for two years after FEP onset.

Follow-up assessmentData on the main antipsychotics and other medications (mood stabilizers, adjuvant antipsychotics, antidepressants) received during the two-year follow-up were obtained from clinical records. In cases in which electroconvulsive therapy was performed, these data were also registered. The antipsychotic dose was converted into chlorpromazine equivalents to facilitate comparisons.33

All of the following variables were assessed at disease onset, at time of clozapine initiation and at the final follow-up (or upon discontinuation of clozapine treatment): body mass index (BMI), blood glucose, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and total cholesterol. Clozapine side effects obtained from clinical records were also recorded during follow-up. Blood analyses were performed under fasting conditions.

We used the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III)31 to define the threshold for metabolic side effects: fasting glucose superior to 100mg/dL, blood pressure superior to 130/85mmHg, serum triglycerides superior to 150mg/dL, serum high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol inferior to 40mg/dL in male and to 50mg/dL in female. Overweight was defined as BMI from 25 to 29.9kg/m2, obesity as BMI≥30kg/m2.

The cohort was stratified into three groups, as follows: (1) clozapine users, (2) patients eligible for clozapine and (3) non-treatment resistant patients. The first group included all patients who received clozapine within two-years of illness onset. The second group consisted of patients who were eligible for clozapine (i.e., who received more than two adequate trials in time and dose of different primary antipsychotics during the study period) but did not receive clozapine. The third group was comprised of non-TR patients (patients who received two or less primary antipsychotics during the study period). The purpose of using this classification system was to differentiate between treatment-resistant patients (clozapine users and clozapine-eligible patients) (3) and non-TR patients.

Clozapine prescription rates between treating clinicians were calculated; however, in the ETEP program, same protocols are followed for clinicians and cases are discussed regularly. Also, for clozapine-eligible patients, reasons for not receiving clozapine were retrieved from medical records when they were detailed.

At two years of follow-up, the GAF was administered to the clozapine users and the clozapine-eligible patients to assess functionality. The improvement in GAF scores was calculated by subtracting the baseline score from the score at the final follow-up.

Statistical analysesThe Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was performed to check for distribution normality. A descriptive analysis of the sample and the variables associated with clozapine use (adverse effects; time to clozapine initiation; previous antipsychotics; discontinuation rate and reasons for discontinuation) was performed.

Univariate analyses were performed to check for difference in sociodemographic and clinical variables at baseline between the patients who completed the full study (completers) and those who dropped out (non-completers). Univariate analyses were performed to compare the baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the three groups (clozapine users, clozapine-eligible patients, and non-TR patients) using the Chi-square or Kruskal–Wallis test, as appropriate. Post hoc tests were performed as appropriate. The U-Mann–Whitney test was performed to assess between-group differences in the improvement in GAF scores.

Univariate analyses were performed between the three groups to check differences in changes between disease onset and end of follow up in body mass index (BMI), blood glucose, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and total cholesterol and blood pressure. Post hoc analyses with Bonferroni correction were done.

To identify the baseline variables associated with clozapine use, a logistic regression model (step-wise method) was performed. Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was performed. The dependent variable was clozapine use (yes/no) and the independent variables included all variables that were significant (p<0.1) on the univariate analysis (baseline diagnosis, heavy smoking, PANSS total, PANSS positive, and GAF). Given that previous studies20,34,35 have shown that sex, age, BMI and duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) are predictors of TR, we also included those variables in the model.

The statistical analyses were performed with the IBM-SPSS Statistics for Windows, v. 20 (IBM Corp.; Armonk, NY, USA). p values≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical approvalThe study was approved by the local ethics committee at the Hospital del Mar approval code: 2022/10517). This study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and fully complied with all local laws governing patient confidentiality and data protection.

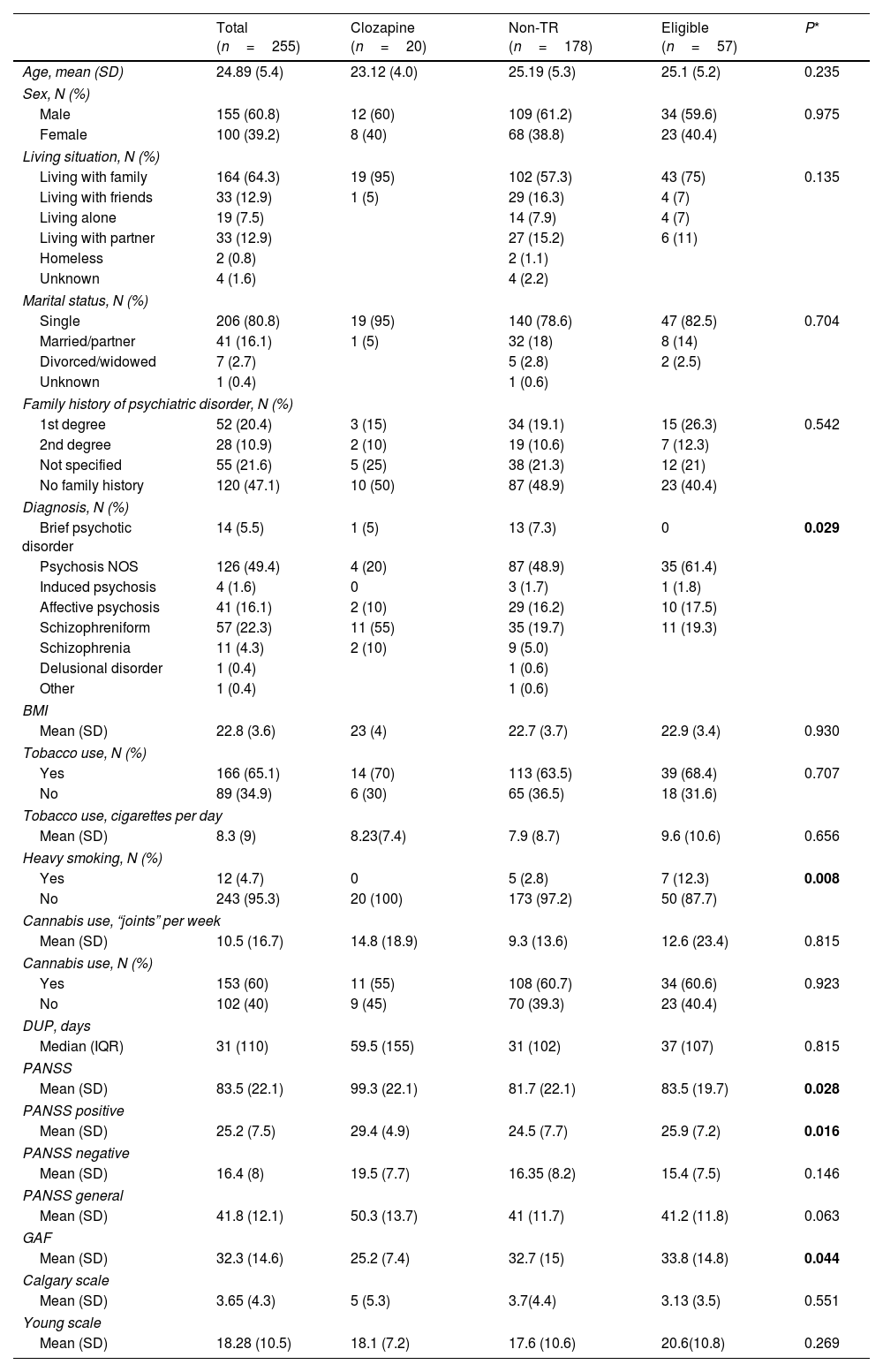

ResultsPatient characteristicsOf the 255 patients initially included in the study, 175 (68.6%) completed the full 2-year follow-up (completers) and 80 patients were lost to follow-up (non-completers). At the end of the follow-up, from 255 patients, 20 were classified as clozapine users, 57 to the clozapine-eligible group and 178 to the non-TR group. The mean (standard deviation [SD]) age of the full cohort (n=255) was 24.9 (5.4). Most of the patients (n=155, 60.8%) were males. Table 1 shows the baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the full sample and Table A.1 in supplementary material compares those characteristics in the completers and non-completers. As Table A.1 shows, the only significant difference between the groups was in living situation.

Baseline sociodemographic and clinical variables in the full sample of FEP patients (n=255) according to treatment group (clozapine users, clozapine-eligible patients, and non-TR patients).

| Total (n=255) | Clozapine (n=20) | Non-TR (n=178) | Eligible (n=57) | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 24.89 (5.4) | 23.12 (4.0) | 25.19 (5.3) | 25.1 (5.2) | 0.235 |

| Sex, N (%) | |||||

| Male | 155 (60.8) | 12 (60) | 109 (61.2) | 34 (59.6) | 0.975 |

| Female | 100 (39.2) | 8 (40) | 68 (38.8) | 23 (40.4) | |

| Living situation, N (%) | |||||

| Living with family | 164 (64.3) | 19 (95) | 102 (57.3) | 43 (75) | 0.135 |

| Living with friends | 33 (12.9) | 1 (5) | 29 (16.3) | 4 (7) | |

| Living alone | 19 (7.5) | 14 (7.9) | 4 (7) | ||

| Living with partner | 33 (12.9) | 27 (15.2) | 6 (11) | ||

| Homeless | 2 (0.8) | 2 (1.1) | |||

| Unknown | 4 (1.6) | 4 (2.2) | |||

| Marital status, N (%) | |||||

| Single | 206 (80.8) | 19 (95) | 140 (78.6) | 47 (82.5) | 0.704 |

| Married/partner | 41 (16.1) | 1 (5) | 32 (18) | 8 (14) | |

| Divorced/widowed | 7 (2.7) | 5 (2.8) | 2 (2.5) | ||

| Unknown | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) | |||

| Family history of psychiatric disorder, N (%) | |||||

| 1st degree | 52 (20.4) | 3 (15) | 34 (19.1) | 15 (26.3) | 0.542 |

| 2nd degree | 28 (10.9) | 2 (10) | 19 (10.6) | 7 (12.3) | |

| Not specified | 55 (21.6) | 5 (25) | 38 (21.3) | 12 (21) | |

| No family history | 120 (47.1) | 10 (50) | 87 (48.9) | 23 (40.4) | |

| Diagnosis, N (%) | |||||

| Brief psychotic disorder | 14 (5.5) | 1 (5) | 13 (7.3) | 0 | 0.029 |

| Psychosis NOS | 126 (49.4) | 4 (20) | 87 (48.9) | 35 (61.4) | |

| Induced psychosis | 4 (1.6) | 0 | 3 (1.7) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Affective psychosis | 41 (16.1) | 2 (10) | 29 (16.2) | 10 (17.5) | |

| Schizophreniform | 57 (22.3) | 11 (55) | 35 (19.7) | 11 (19.3) | |

| Schizophrenia | 11 (4.3) | 2 (10) | 9 (5.0) | ||

| Delusional disorder | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) | |||

| Other | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) | |||

| BMI | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 22.8 (3.6) | 23 (4) | 22.7 (3.7) | 22.9 (3.4) | 0.930 |

| Tobacco use, N (%) | |||||

| Yes | 166 (65.1) | 14 (70) | 113 (63.5) | 39 (68.4) | 0.707 |

| No | 89 (34.9) | 6 (30) | 65 (36.5) | 18 (31.6) | |

| Tobacco use, cigarettes per day | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 8.3 (9) | 8.23(7.4) | 7.9 (8.7) | 9.6 (10.6) | 0.656 |

| Heavy smoking, N (%) | |||||

| Yes | 12 (4.7) | 0 | 5 (2.8) | 7 (12.3) | 0.008 |

| No | 243 (95.3) | 20 (100) | 173 (97.2) | 50 (87.7) | |

| Cannabis use, “joints” per week | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 10.5 (16.7) | 14.8 (18.9) | 9.3 (13.6) | 12.6 (23.4) | 0.815 |

| Cannabis use, N (%) | |||||

| Yes | 153 (60) | 11 (55) | 108 (60.7) | 34 (60.6) | 0.923 |

| No | 102 (40) | 9 (45) | 70 (39.3) | 23 (40.4) | |

| DUP, days | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 31 (110) | 59.5 (155) | 31 (102) | 37 (107) | 0.815 |

| PANSS | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 83.5 (22.1) | 99.3 (22.1) | 81.7 (22.1) | 83.5 (19.7) | 0.028 |

| PANSS positive | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 25.2 (7.5) | 29.4 (4.9) | 24.5 (7.7) | 25.9 (7.2) | 0.016 |

| PANSS negative | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 16.4 (8) | 19.5 (7.7) | 16.35 (8.2) | 15.4 (7.5) | 0.146 |

| PANSS general | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 41.8 (12.1) | 50.3 (13.7) | 41 (11.7) | 41.2 (11.8) | 0.063 |

| GAF | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 32.3 (14.6) | 25.2 (7.4) | 32.7 (15) | 33.8 (14.8) | 0.044 |

| Calgary scale | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.65 (4.3) | 5 (5.3) | 3.7(4.4) | 3.13 (3.5) | 0.551 |

| Young scale | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 18.28 (10.5) | 18.1 (7.2) | 17.6 (10.6) | 20.6(10.8) | 0.269 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; FEP, first episode psychosis; IQR, interquartile range; DUP, duration of untreated psychosis; GAF, global assessment of functioning; N, sample size; non-TR, non-treatment resistant; PANSS, positive and negative symptom scale; SD, standard deviation.

Post hoc analyses: diagnosis (non-TR vs. clozapine p=0.038; non-TR vs. eligible p=0.250; eligible vs. clozapine p=0.001); heavy smoking (non-TR vs clozapine p=0.448; non-TR vs eligible p=0.005; eligible vs clozapine p=0.1); total PANSS (non-TR vs. clozapine p=0.008; non-TR vs. eligible p=0.772; eligible vs. clozapine p=0.027), PANSS positive (Non-TR vs. clozapine p=0.007; non-TR vs. eligible p=0.522; eligible vs. clozapine p=0.112), and GAF (non-TR vs. clozapine p=0.017; non-TR vs. eligible p=0.737; eligible vs. clozapine p=0.019).

Of the total sample (n=255), 77 (30.2%) underwent more than two trials of antipsychotics during the follow-up period. Of these 77 patients, 20 (20/255, 7.8%) received clozapine while 57 (57/255, 22.4%) did not. The rest of the sample (n=178, 69.8%) received 2 or less trials of primary antipsychotic.

Clozapine usersThe median (interquartile range [IQR]) time to clozapine initiation was 55.0 (93.3) days. During follow-up, the mean (SD) dose of clozapine was 296.3 (77.9)mg, and the mean (SD) blood concentration was 372.8 (165.2)ng/ml.

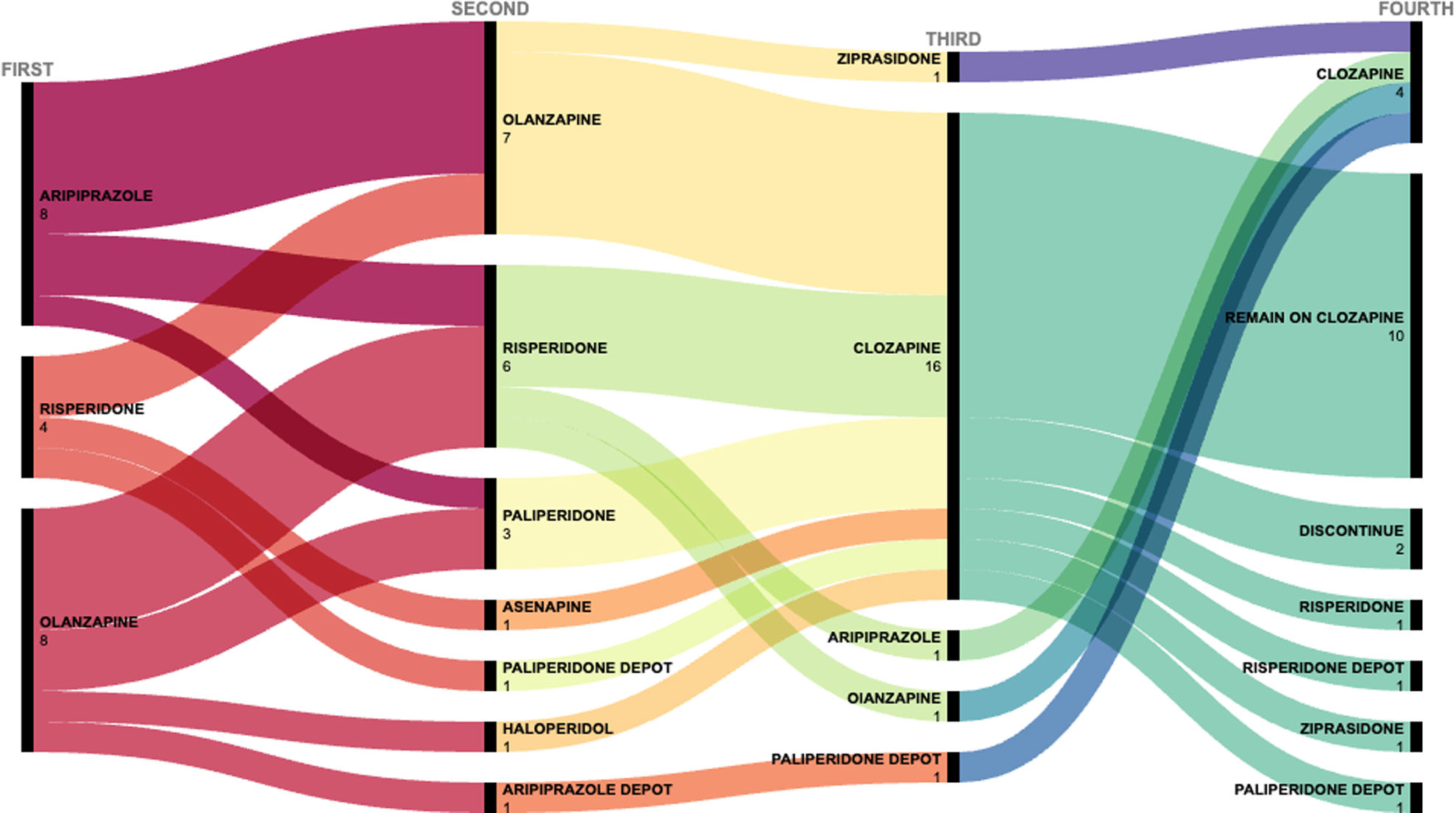

Clozapine was prescribed after two trials of other antipsychotics in 16 of the 20 cases and after three trials in the remaining four cases. The antipsychotic trials performed in the clozapine users are shown in Fig. 1 and Table A.2 in Supplementary Material.

Seven of the 20 patients (35%) who received clozapine discontinued treatment. In two cases, treatment was discontinued by clinician decision due to adverse events (persistent tachycardia and urinary incontinence in one patient and sialorrhea, sedation, obsessive symptoms and relative neutropenia in the other). In the other five patients, four failed to adhere to treatment and one received clozapine as the fourth antipsychotic but requested a switch to a different medication.

The reported adverse effects in the clozapine group are described in Table 2. The most common adverse effect was sedation (75%) followed by hypersalivation (35%). Metabolic side effects were observed in more than half (55%, n=11) of these patients. At the end of follow-up, 30% of patients met criteria for obesity and 25% for overweight. Changes in weight, blood pressure, and biochemical parameters for clozapine users and the other two groups are shown in Table 3. Differences in changes between groups were found for BMI (p=0.001) and triglycerides (p<0.001). After post hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction: BMI (clozapine vs eligible p<0.001; clozapine vs non-TR p=0.004; eligible vs non-TR p=1.00); triglycerides (clozapine vs eligible p=0.007; clozapine vs non-TR p<0.001; eligible vs non-TR p=0.675). Concomitant drug treatments are shown in Table A.3 in Supplementary Material.

Clozapine side effects in clozapine users (n=20) during the 2-year follow-up period.

| Side effect | N | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sedation | 15 | 75 |

| Hypersalivation | 7 | 35 |

| Obesity | 6 | 30 |

| Overweight | 5 | 25 |

| Serum triglycerides>150mg/dL | 5 | 25 |

| HDL cholesterol<40mg/dL in male and <50mg/dL in female | 5 | 25 |

| Fasting glucose>100mg/dL | 4 | 20 |

| Tachycardia | 3 | 15 |

| Postural hypotension | 2 | 10 |

| Blood pressure>130/85mmHg | 2 | 10 |

| Enuresis | 2 | 10 |

| Obsessive symptoms | 2 | 10 |

| Relative neutropenia | 1 | 5 |

Changes in BMI, blood pressure and biochemical parameters during follow-up for clozapine users, clozapine-eligible patients, and non-TR patients.

| Clozapine users | Clozapine-eligible patients | Non-TR patients | P* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease onset | Clozapine initiation | End of follow-up | Disease onset | End of follow-up | Disease onset | End of follow-up | ||

| BMI | 23 (4) | 26.2 (7) | 30.1 (7) | 22.9 (3.4) | 25.5 (4.7) | 22.7 (3.6) | 25.8 (5.3) | 0.001 |

| Fasting blood glucose, mg/dL | 92 (16) | 86 (9) | 95.7 (11) | 87.3 (11.6) | 87.4 (11) | 85.7 (8.1) | 86.7 (14) | 0.105 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dL | 148 (29) | 170 (39) | 188 (27) | 149 (32) | 172 (42) | 145 (28) | 161 (34.4) | 0.105 |

| HDL, mg/dL | 55 (14) | 51 (14) | 41 (11) | 52.2 (16.7) | 53.8 (16.6) | 49.9 (14) | 53 (17) | 0.223 |

| LDL, mg/dL | 76 (30) | 97 (35) | 125 (24) | 89.1 (28) | 108.3 (39.2) | 82.1 (22.3) | 98.7 (27.8) | 0.120 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 72 (29) | 83 (45) | 165 (74) | 76.5 (46) | 110 (62) | 84 (48) | 96.2 (64) | <0.001 |

| Blood pressure, mmHg | ||||||||

| Systolic | 119 (10) | 123 (9) | 131 (13) | 118 (13) | 120 (9) | 116 (12) | 118 (12) | 0.103 |

| Diastolic | 79 (12) | 77 (10) | 79 (10) | 71 (8) | 70.8 (9.6) | 72 (11) | 73 (10) | 0.865 |

Note: All values are presented as means with standard deviation (SD).

Of the 77 patients who received more than two antipsychotic trials (i.e., clozapine users and clozapine-eligible patients), 43 had as main prescriber A.M. who prescribed clozapine in 12 out of 43 (28%) patients and 34 had another main prescriber (D.B.) who prescribed clozapine in 8 out of 34 (24%) patients.

Of the 57 patients eligible for clozapine, in 13 cases, patients clearly refused initiating clozapine when indicated by their clinicians. For the remaining cases, the reasons why patients did not receive clozapine was not due to a single cause but to the confluence of multiple factors including patient and family preferences, clinician's decision and psychosocial conditions.

Comparison of baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics between clozapine users, clozapine-eligible patients, and non-TR patientsThe univariate analysis revealed statistically significant differences between the three groups in the following baseline variables: diagnosis (χ2=25.628; p=0.029); heavy smoking (χ2=9.709; p=0.008); total PANSS (k=7.152; p=0.028); PANSS positive (k=8.251; p=0.016); and GAF (k=6.250; p=0.044). Post hoc analyses appear as a footnote in Table 1. After adjusting for multiple comparison (0.05/20=0.0025), none of the variables remained significant.

Predictors of clozapine useOn the multivariate analysis (R2=0.09), the only variable that was significant over the two-year follow-up was baseline GAF score (B=−0.07; OR=0.94; 95% CI: 0.88–0.99; p=0.019). Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was performed (χ2=16.13; p=0.061).

Functionality at two yearsAt two-years of follow-up, the mean (SD) GAF score in clozapine users was 67.5 (12.3) versus 70.1 (10.7) for clozapine-eligible patients.

GAF scores improved from baseline to the final follow-up by a mean (SD) of 42.9 (13.5) points in the clozapine users and by 36.8 (16.8) in clozapine-eligible patients. These differences were not statistically significant (U=227.00, p=0.111).

DiscussionThe present study was performed to better characterize clozapine prescription patterns in a real-world setting of FEP patients under treatment at a specialized program at a university hospital. Clozapine was prescribed in 20 of the 255 patients (7.8%) during the 2-year follow-up. We found that lower baseline GAF score was associated with clozapine use within two years. As these findings show, only 26% (20/77) of patients who were candidates for clozapine actually received it.

None of the patients who were prescribed clozapine received it as a first or second trial, even if some studies suggest possible benefit from early use of clozapine in some patients.11,12 This could be explained by the legal requirements for clozapine prescription in our country. Furthermore, the relative low number of long-acting injectable antipsychotics used before clozapine prescription in our sample could be explained in part by the requirements (including the existence of limitations and specific criteria for prescription) that were present at that time in our hospital.

Although the proportion of patients who received clozapine (7.8%) in this sample was consistent or higher than some studies,23,27 it was lower than reported in many others.20,24,35,36 Several factors could account for this lower prescription rate, most importantly the relatively short follow-up period (2 years) versus several other studies23,24,27,35,36 that had a follow-up period of 10 years or more. The prescription rate in our sample does not include any of the patients in whom clozapine was prescribed after the end of the follow-up period.20 Furthermore, due to the short follow-up, we may have failed to identify patients in whom the treating clinician decided to delay initiation of clozapine17,23 or in cases in which the patient (or family) initially refused early treatment but later agreed to receive clozapine. In addition, differences between the studies in terms of inclusion/exclusion criteria could have affected the results. For example, we included patients diagnosed with brief psychotic disorder or affective psychosis—who are more likely to have better outcomes than patients diagnosed with schizophrenia (and thus less likely to need clozapine)—whereas other studies have excluded these patients.36,37 Nevertheless, clozapine prescription rate in our sample is in line with reported prescriptions rates in multicenter studies with similar designs in the same environment.38

In our sample, clozapine was prescribed as either the third or fourth antipsychotic in 16 (80%) and four (20%) patients. This prescription pattern more closely adheres to the recommendations of clinical guidelines than some other studies,23,24 which would explain the shorter median time to clozapine initiation in our study compared with the delays in clozapine initiation found previous in the literature ranging from 19.3 weeks to 5.5 years or 47.7 months.17,18,27

The most common adverse effects in the clozapine users were sedation, hypersalivation, and metabolic alterations, which is consistent with previous reports.24,25 Moreover, clozapine users had significant changes in BMI and triglycerides over two years compared to the other two groups (Table 3). Like most early intervention programs, our program (ETEP) promotes a healthy diet and active lifestyle through a multidisciplinary care approach. Despite these interventions, metabolic alterations appeared frequently in FEP patients treated with clozapine; thus, more intensive multidisciplinary, including pharmacological approaches, should also be considered.39,40

Antipsychotic polypharmacy before clozapine initiation was frequent for clozapine users in our sample (A.3 in Supplementary Material). However, most of these drugs—mainly antipsychotics with high sedative effects such as olanzapine or haloperidol—were prescribed during hospitalization, probably to reduce or prevent agitation.

On the univariate analysis, significant between-group differences were observed in five variables at baseline: diagnosis, heavy smoking, PANSS total score, PANSS positive score, and GAF score, but none of these comparisons survived Bonferroni correction. On the multivariate analysis, the only variable that was a significantly associated with clozapine use was the GAF score, with lower scores at baseline in the clozapine group (Table 1).

We found trend differences regarding baseline diagnosis between groups, showing a higher proportion of schizophreniform diagnosis for clozapine users. Two studies—one by Rowntree et al. and another by Doyle et al.24,25—sought to determine whether there were differences between clozapine and non-clozapine users in baseline diagnosis. Both studies showed a tendency with a higher proportion of schizophrenia diagnosis at baseline in clozapine users but neither of them found any statistically significant difference. However, the study by Crespo-Facorro et al.41 found that a schizophrenia diagnosis at baseline was associated with a lack of response to treatment. Similarly, Demjaha et al.35 found that schizophrenia was a predictor of TR.

In our study, the PANSS total score at baseline was significantly higher in clozapine users than in the clozapine-eligible group and the non-TR group, although these differences did not survive Bonferroni correction (Table 1). Studies that have assessed the value of baseline psychotic symptom severity as a predictor of treatment resistance have reported inconclusive results.2,42 A systematic review by Bozzatello et al.34 found that higher negative symptoms at baseline was a better predictor of TR in patients with FEP than higher severity of positive or total symptoms.

On the multivariate analysis, the only variable significantly associated with a higher likelihood of clozapine use was the baseline GAF score. However, with the present study, we were not able to establish causation or the direction of the association. Despite that, this finding is in line with the results of the study by Horsdal et al., who found that lower (worse) GAF scores at first diagnosis of schizophrenia were associated with the development of treatment resistance within two years of diagnosis.43

In our sample, the clozapine users had lower baseline GAF scores—indicating worse functionality—than in clozapine-eligible patients. During follow-up, the GAF scores in clozapine users increased more than the scores in clozapine-eligible patients, a finding that suggests clozapine use could improve functionality compared to other antipsychotics in TR FEP patients. That said, no definitive conclusions can be drawn given that these differences were not statistically significant, perhaps due to the limited number of clozapine users. Clozapine users had lower GAF scores and higher psychotic symptomatology at baseline, which could explain why clinicians were more likely to prescribe clozapine in those patients than in clozapine-eligible patients, whose baseline symptoms were less severe.

Strengths and limitationsThis study has several limitations. First, the observational design does not allow us to establish causation. Second, the small number of clozapine users (n=20) limits the power of the study. Third, since we limited follow-up to a maximum of two years, we may not have identified patients who were prescribed clozapine after the study period. Fourth, we did not use any standardized scale to measure clozapine side effects. However, as part of our protocol, a complete assessment of side effects was performed regularly. By contrast, the main strength of the study is the naturalistic real-world design and comprehensive assessment of the characteristics of clozapine use in a FEP sample.

ConclusionAlthough clozapine is considered the treatment of choice for treatment resistant schizophrenia, it remains underutilized in FEP patients. In this study, baseline functionality (GAF score) was associated with clozapine use. More studies are needed to identify other clinical and neurobiological factors that could predict treatment resistance and clozapine use. Given the potentially severe adverse effects of clozapine in patients with FEP, targeted multidisciplinary interventions are needed to prevent or ameliorate these negative side effects in this young patient population.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestDr. Mané and Dr. Bergé have both received financial support to attend meetings, travel support, and served as speakers for Otsuka, Angelini and Janssen Cilag. The other authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to report.

We would like to thank all the patients and their families who made this study possible. We also thank Bradley Londres for professional English-language editing.