Processing speed (PS) deficits represent a fundamental aspect of cognitive impairment, evident not only in schizophrenia but also in individuals undergoing their first episode of psychosis (FEP) and their unaffected first-degree relatives. Heterogeneity in tests assessing PS reflects the participation of motor and cognitive subcomponents to varying degrees. We aim to explore differences in performance of the subcomponents of PS in FEP patients, parents, siblings, and controls.

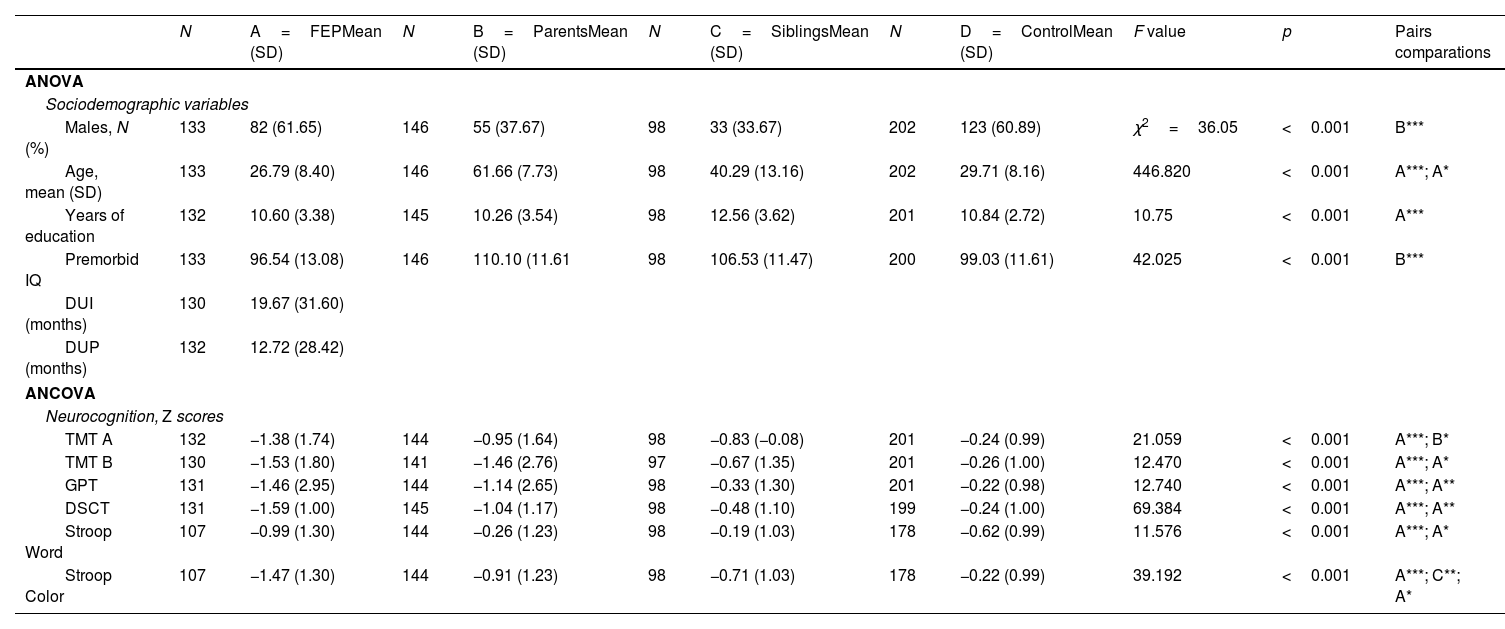

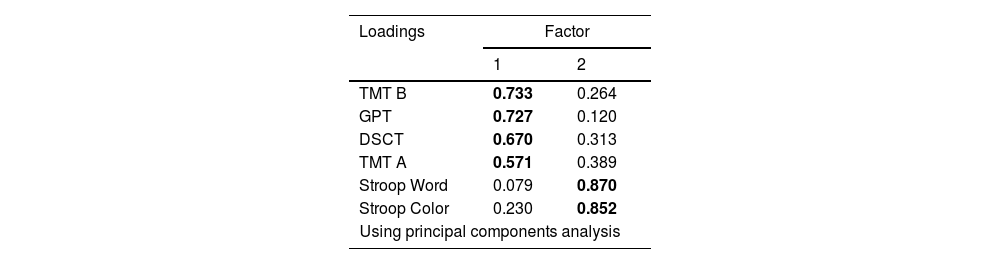

Materials and methodsResults from tests, including Trail Making Test part A and part B, Digit Symbol Coding Test, Grooved Pegboard Test, and Stroop Word and Stroop Color subtests, were obtained from 133 FEP patients, 146 parents, and 202 controls. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was employed in controls to establish the structure, followed by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to verify if the other groups share this structure.

ResultsEFA revealed a two-factor model: Factor 1 for the motor subcomponent and Factor 2 for the cognitive subcomponent. Subsequently, CFA indicated a good fit for the remaining groups with differences in the relationship between the factors.

ConclusionsDifferences in the relationships of factors within a common structure suggest the involvement of different compensatory strategies among groups, providing insights into the underlying mechanisms of PS deficits in patients and relatives.

Article

(Sociedad Española de Psiquiatría y Salud Mental)

Diríjase al área de socios de la web de la SEPSM, (https://sepsm.org/revista/) y autentifíquese.