Managing patient with suicidal thoughts and behaviours presents significant challenges due to the scarcity of robust evidence and clear guidance. This study sought to develop a comprehensive set of practical guidelines for the assessment and management of suicidal crises.

Materials and methodsUtilizing the Delphi methodology, 80 suicide clinician and research experts agreed on a series of recommendations. The process involved two iterative rounds of surveys to assess agreement with drafted recommendations, inviting panellists to comment and vote, culminating in 43 consensus recommendations approved with at least 67% agreement. These consensus recommendations fall into three main categories: clinical assessment, immediate care, and long-term approaches.

ResultsThe panel formulated 43 recommendations spanning suicidal crisis recognition to continuous long-term care. These guidelines underscore systematic proactive suicide risk screening, in-depth medical and toxicological assessment, and suicide risk appraisal considering personal, clinical factors and collateral information from family. The immediate care directives emphasize a secure environment, continuous risk surveillance, collaborative decision-making, including potential hospitalization, sensible pharmacological management, safety planning, and lethal means restriction counselling. Every discharge should be accompanied by prompt follow-up care incorporating proactive case management and multi-modal approach involving crisis lines, brief contact, and psychotherapeutic and pharmacological interventions.

ConclusionsThis study generated comprehensive guidelines addressing care for individuals in suicidal crises, covering pre- to post-discharge care. These practical recommendations can guide clinicians in managing patients with suicidal thoughts and behaviours, improve patient safety, and ultimately contribute to the prevention of future suicidal crises.

Suicidal thoughts and behaviours (STB) are responsible for around one-third of psychiatric Emergency Department (ED) visits, making them among the most frequently seen mental health-related situations in the ED.1 The other way round, the ED is often the first point of contact with the healthcare system for suicide attempters and individuals in suicidal crisis.2 Notably, up to half of individuals that died by suicide had an interaction with the healthcare system within one month prior to their suicide, which frequently was an ED visit.3 ED is, therefore, well-positioned to play a vital part in successfully identifying individuals with STB, managing the current crisis, and preventing future STBs.4

However, a suicidal crisis can be challenging not only for the individual experiencing it but also for the staff that have to grapple with decisions regarding appropriate care, with implications for patient safety and recovery.5 Studies have noted that STB elicit mostly negative feelings among staff members, contrary to other psychiatric diagnoses.6 Indeed, clinicians taking care of individuals at imminent risk of suicide are more overwhelmed and distressed by their patients compared to clinicians taking care of non-suicidal patients.7 Part of these feelings stems from the high level of responsibility and uncertainty associated with STB. Indeed, clinically, we remain largely unable to accurately identify individuals who will (re-)attempt or die by suicide, as the predictive value of even the best clinical risk factors is poor to non-existent.8 Given the organizational and ethical challenges in conducting research with this population, the evidence on many current clinical practices is lacking.

Having a clear, intentional plan of steps in case of suicidal crisis helps patients make better decisions.9 In this logic, guidelines for clinicians caring for such patients could help resolve clinician's uncertainty associated to such situation. The most recent European guidance on suicide treatment and prevention dates back more than ten years ago,10 and therefore lack several new interventions that have gained substantial scientific and clinical support in the last decade, such as safety planning, counselling on access to lethal means, and ketamine and esketamine use in crisis.9,11 To fill this gap, we conducted a modified Delphi method seeking opinions from clinician experts in the suicidology field to create broad European recommendations, addressing the steps from clinical evaluation, immediate risk management, and connection to long-term care. We aimed to create pragmatic recommendations for clinicians on the assessment and management of patients presenting with acute suicidal ideation or a recent suicide attempt.

Materials and methodsGeneral approach and generation of the initial draft consensus recommendationsUsing a modified Delphi technique (the process is summarized in Fig. 1), we sought expert recommendations for managing suicidal crises. This method was chosen since concrete data in some areas is unavailable.12 Our team of eight STB experts (core group) discussed the method online, then grouped into four groups of two to work on the following domains: assessment, immediate care, long-term interventions, and post-care. Members reviewed practices, guidelines, and literature until March 2022 (based on Pubmed/Medline search) to draft initial recommendations for each domain. The broad scope prevented a formal systematic review. The core group then met in-person and finalized 46 initial recommendations in three areas (assessment, immediate care, and interventions with long-term approach (two areas were merged due to a substantial overlap)).

Delphi panel generation and data collection. Study methodology, including sample and data collection. Expert panel was selected from the members of the European Psychiatry Association Suicidology Section and complimented with clinicians that are prominent in suicidology research from around the Europe. After the initial statement draft, the first round of online survey (R1) was carried out, and it included text boxes for panellists to provide comments and suggest edits. Then, the core group met again to discuss the statements, comments, and draft the final recommendations that were sent for the second round of online survey (R2). In this round, the panel could comment, but the statements were no longer modified given the substantial level of agreement reached by this stage. The final core group meeting evaluated the final set of recommendations and provided feedback for recommendations. RR: response rate.

The core group members identified 148 experts in the suicide field who met the following inclusion criteria: being a specialist psychiatrist in Europe, a fluent English speaker, and actively consulting and/or conducting research on individuals with STB. The invited participants were either members of the European Psychiatry Association Suicidology section or first or senior authors of at least three published articles relating to STB. We used the Survey Monkey platform to distribute the surveys to the panellists, with three automatic reminders for each round. The answers were anonymous, as recommended for Delphi surveys.13 At the beginning of the survey, the study was described to the invitees, the key definitions were provided (Supplementary file 1), and the panellists were instructed to take part only if they considered their expertise applicable to the subject matter. Informed consent was obtained from each panellist before each round of the survey. The panellists voted on recommendations on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, no opinion, disagree, strongly disagree) and were invited to comment on each recommendation. We decided a priori to use a supermajority (that is, ≥67% combined agreement with either “strongly agree” or “agree”, or “strongly disagree” or “disagree”) minimum cut-off for consensus. Panellists also provided their sociodemographic and work data.

Generation of final consensus recommendationsAfter obtaining the panellists’ feedback on the initial recommendations, the core group met again to revise the initial recommendations based on the panellists’ comments and the level of agreement. A new set of recommendations was then generated by modifying the recommendations with low-to-moderate agreement and adding two new recommendations that emerged in the panellists’ comments. These recommendations were then sent to the panellists that took part in the first round for a second round (R2), inviting the panellists to vote. They also had an opportunity to comment, but no modifications were made after this survey round, given a substantial level of consensus obtained. The core group then met again in-person to discuss the final set of recommendations.

Data analysisWe ran frequencies of all recommendations and calculated the levels of agreement/for each recommendation. The core team also analyzed the qualitative data (open-ended comments: n=344 comments in R1 and n=58 comments in R2). The comments were first reviewed individually by at least three core group members and then discussed within the core group after each survey round. After the first round, comment suggestions were incorporated into revised recommendations. The final quantitative analysis involved assigning each recommendation a grade to indicate the level of combined agreement, using a system that has been used in other recent Delphi studies,14 in which ‘U’ denotes unanimous (100%) agreement; ‘A’ denotes 90–99% agreement; ‘B’ denotes 78–89% agreement; and ‘C’ denotes 67–77% agreement.

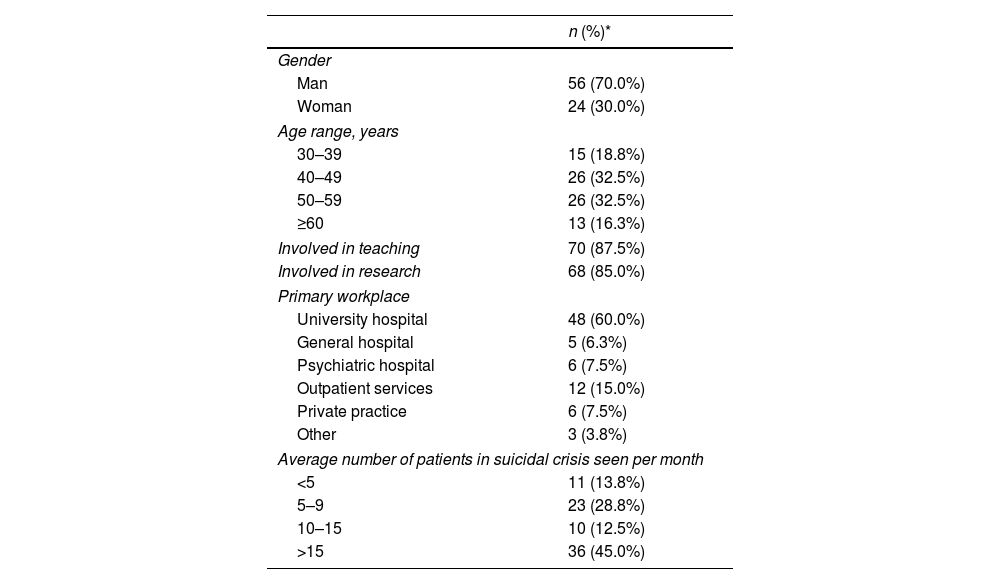

ResultsOverviewOut of 148 invitees, 80 participants (54.1%) from 19 countries responded to the first round of surveying. Among respondents, 70% identified as men, and 65% were between the ages 40 and 59 years. The majority of panellists work in university hospitals, interact with at least ten patients in suicidal crisis per month, and are involved in teaching or research (see Table 1). Following three core group discussions and two online surveys, 28 recommendations gained sufficient consensus in round 1, four were excluded as lacking consensus, 14 revised and one new recommendation were proposed for the second round, where they all reached consensus, yielding 43 final consensus recommendations (≥67% overall agreement).

Characteristics of panel.

| n (%)* | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Man | 56 (70.0%) |

| Woman | 24 (30.0%) |

| Age range, years | |

| 30–39 | 15 (18.8%) |

| 40–49 | 26 (32.5%) |

| 50–59 | 26 (32.5%) |

| ≥60 | 13 (16.3%) |

| Involved in teaching | 70 (87.5%) |

| Involved in research | 68 (85.0%) |

| Primary workplace | |

| University hospital | 48 (60.0%) |

| General hospital | 5 (6.3%) |

| Psychiatric hospital | 6 (7.5%) |

| Outpatient services | 12 (15.0%) |

| Private practice | 6 (7.5%) |

| Other | 3 (3.8%) |

| Average number of patients in suicidal crisis seen per month | |

| <5 | 11 (13.8%) |

| 5–9 | 23 (28.8%) |

| 10–15 | 10 (12.5%) |

| >15 | 36 (45.0%) |

Five recommendations reached the unanimous agreement: actively questioning patients about their suicidal ideation, intent, and preparation (REC 1.4), incorporating comprehensive patient history in suicide risk assessment (REC 1.7), intensive monitoring of inpatients at very high suicide risk (REC 2.5), systematically proposing safety planning before discharge (REC 2.13); and ensuring that patients receive follow-up care information, necessary prescriptions, and crisis service contact information (REC 3.1) (Tables 2–4).

Consensus statements on the assessment of an individual in suicidal crisis.

| Recommendation | Grade | Agreement | |

|---|---|---|---|

| REC 1.1 | Psychiatrists should systematically evaluate suicide risk in all patients they see in a consultation. | B | 88.7% |

| REC 1.2 | A patient with a past-year history of suicide attempt should be referred to a mental health professional if there has not been a psychiatric evaluation since the attempt. | B | 82.7% |

| REC 1.3 | In most cases, a well-performed clinical assessment allows individuals at high risk of suicidal behaviour to be detected. | B | 88.6% |

| REC 1.4 | All patients with a suicidal crisis should be actively questioned regarding their current suicidal ideation, intent and preparation. | U | 100% |

| REC 1.5 | When assessing suicidal ideation, clinicians should consider the possibility of ambivalence and denial. | A | 94.9% |

| REC 1.6 | Using a validated scale, such as the MINI Suicide Risk Assessment Scale or Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale, can be helpful, but is not a substitute for a clinical evaluation when assessing suicide risk. | A | 92.3% |

| REC 1.7 | The suicide risk assessment should include psychiatric, somatic, psychological and social history, as well as number, severity and violence of previous suicide attempts. | U | 100% |

| REC 1.8 | When assessing suicidal ideation, clinicians should consider the risk of the influence of psychoactive substances, especially following benzodiazepine and alcohol intoxication. | A | 93.7% |

| REC 1.9 | After a suicide attempt, individuals should undergo a focused medical and toxicological assessment, including at least a measurement of blood alcohol concentration, before the psychiatric evaluation. | B | 88.5% |

| REC 1.10 | If the patient is currently intoxicated, especially with benzodiazepines and alcohol, medical decision-making should be postponed. | B | 86.5% |

| REC 1.11 | During the clinical assessment, the psychiatrist ideally should systematically seek additional information from the patient's family members or other people of trust. | A | 94.4% |

| REC 1.12 | In case of a high suspected risk of suicidal behaviour, the psychiatrist may contact the family members against the will of the patient. | C | 74.7% |

Presented in temporal order of care rather than the percentage of agreement. Grades are based on the percentage of combined agreement (agree+somewhat agree). U, unanimous (100%) agreement; A, 90–99% agreement; B, 78–89% agreement; C, 67–77% agreement. Agreement is the highest final agreement in the second round, except from the cases when agreement was higher in the first round, and initial statement was kept instead.

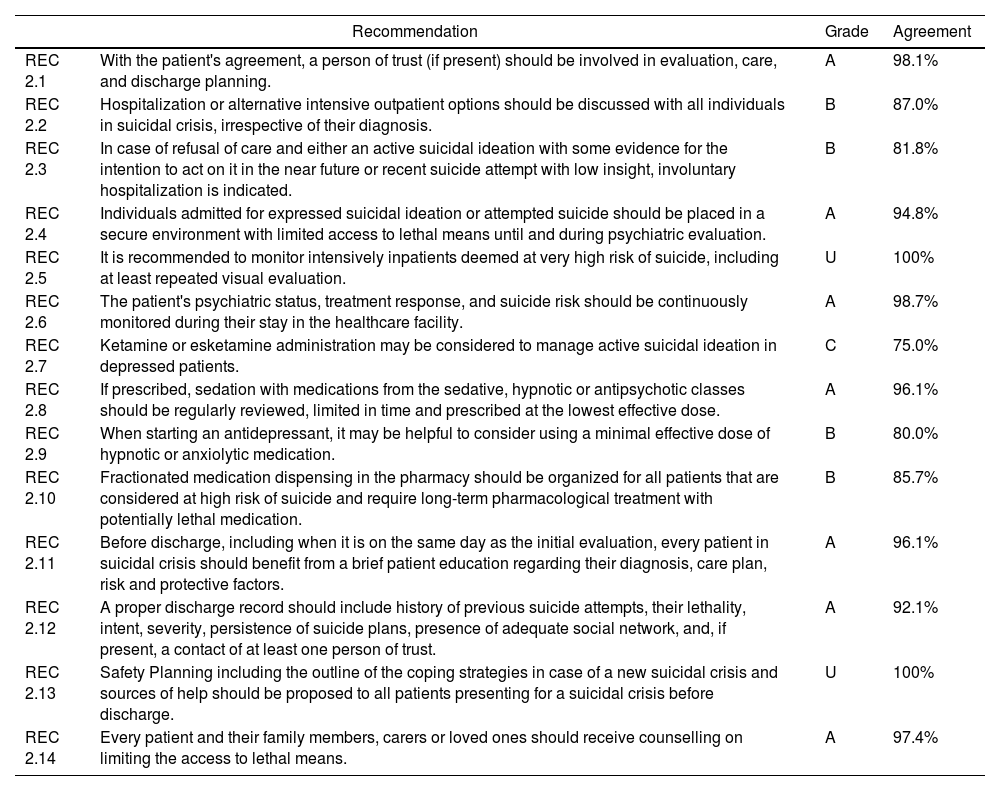

Consensus recommendations on the immediate care of an individual in suicidal crisis.

| Recommendation | Grade | Agreement | |

|---|---|---|---|

| REC 2.1 | With the patient's agreement, a person of trust (if present) should be involved in evaluation, care, and discharge planning. | A | 98.1% |

| REC 2.2 | Hospitalization or alternative intensive outpatient options should be discussed with all individuals in suicidal crisis, irrespective of their diagnosis. | B | 87.0% |

| REC 2.3 | In case of refusal of care and either an active suicidal ideation with some evidence for the intention to act on it in the near future or recent suicide attempt with low insight, involuntary hospitalization is indicated. | B | 81.8% |

| REC 2.4 | Individuals admitted for expressed suicidal ideation or attempted suicide should be placed in a secure environment with limited access to lethal means until and during psychiatric evaluation. | A | 94.8% |

| REC 2.5 | It is recommended to monitor intensively inpatients deemed at very high risk of suicide, including at least repeated visual evaluation. | U | 100% |

| REC 2.6 | The patient's psychiatric status, treatment response, and suicide risk should be continuously monitored during their stay in the healthcare facility. | A | 98.7% |

| REC 2.7 | Ketamine or esketamine administration may be considered to manage active suicidal ideation in depressed patients. | C | 75.0% |

| REC 2.8 | If prescribed, sedation with medications from the sedative, hypnotic or antipsychotic classes should be regularly reviewed, limited in time and prescribed at the lowest effective dose. | A | 96.1% |

| REC 2.9 | When starting an antidepressant, it may be helpful to consider using a minimal effective dose of hypnotic or anxiolytic medication. | B | 80.0% |

| REC 2.10 | Fractionated medication dispensing in the pharmacy should be organized for all patients that are considered at high risk of suicide and require long-term pharmacological treatment with potentially lethal medication. | B | 85.7% |

| REC 2.11 | Before discharge, including when it is on the same day as the initial evaluation, every patient in suicidal crisis should benefit from a brief patient education regarding their diagnosis, care plan, risk and protective factors. | A | 96.1% |

| REC 2.12 | A proper discharge record should include history of previous suicide attempts, their lethality, intent, severity, persistence of suicide plans, presence of adequate social network, and, if present, a contact of at least one person of trust. | A | 92.1% |

| REC 2.13 | Safety Planning including the outline of the coping strategies in case of a new suicidal crisis and sources of help should be proposed to all patients presenting for a suicidal crisis before discharge. | U | 100% |

| REC 2.14 | Every patient and their family members, carers or loved ones should receive counselling on limiting the access to lethal means. | A | 97.4% |

Presented in temporal order of care rather than the percentage of agreement. Grades are based on the percentage of combined agreement (agree+somewhat agree). U, unanimous (100%) agreement; A, 90–99% agreement; B, 78–89% agreement; C, 67–77% agreement. Agreement is the highest final agreement in the second round, except from the cases when agreement was higher in the first round, and initial statement was kept instead.

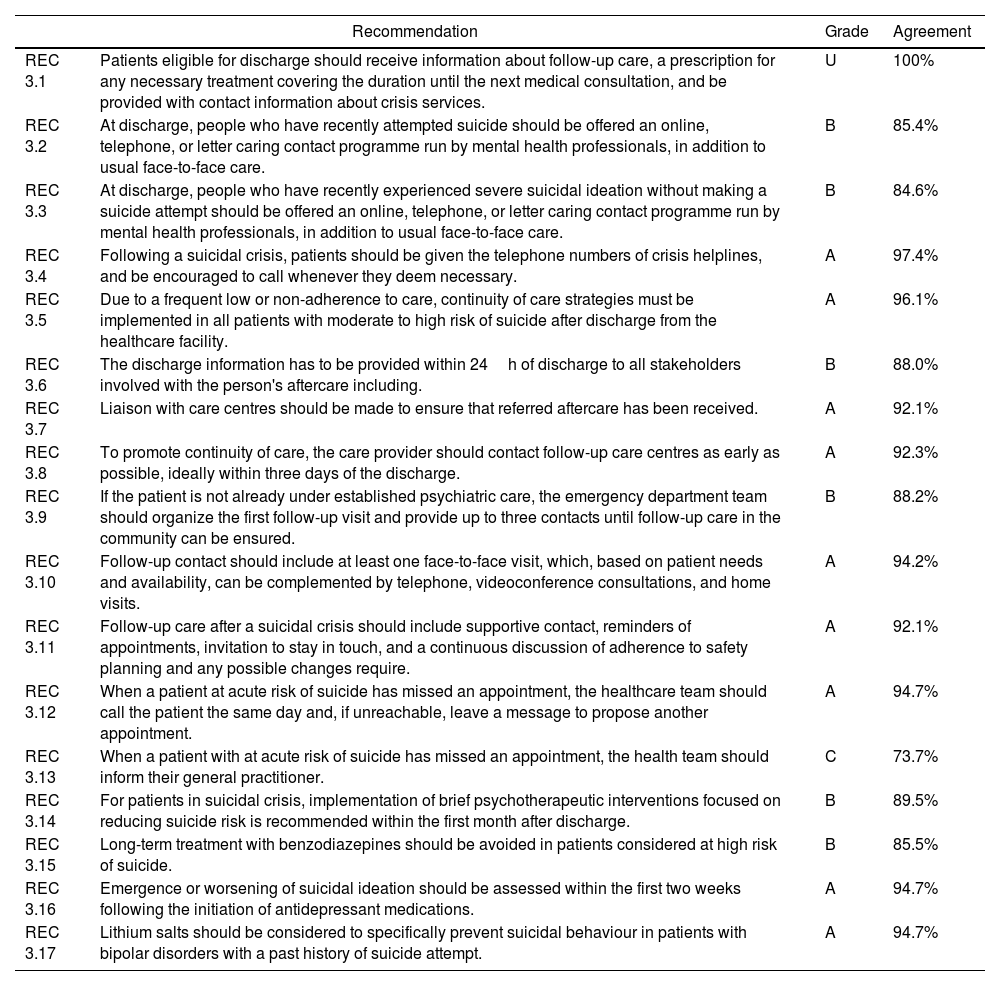

Consensus statements on the interventions with long-term approach.

| Recommendation | Grade | Agreement | |

|---|---|---|---|

| REC 3.1 | Patients eligible for discharge should receive information about follow-up care, a prescription for any necessary treatment covering the duration until the next medical consultation, and be provided with contact information about crisis services. | U | 100% |

| REC 3.2 | At discharge, people who have recently attempted suicide should be offered an online, telephone, or letter caring contact programme run by mental health professionals, in addition to usual face-to-face care. | B | 85.4% |

| REC 3.3 | At discharge, people who have recently experienced severe suicidal ideation without making a suicide attempt should be offered an online, telephone, or letter caring contact programme run by mental health professionals, in addition to usual face-to-face care. | B | 84.6% |

| REC 3.4 | Following a suicidal crisis, patients should be given the telephone numbers of crisis helplines, and be encouraged to call whenever they deem necessary. | A | 97.4% |

| REC 3.5 | Due to a frequent low or non-adherence to care, continuity of care strategies must be implemented in all patients with moderate to high risk of suicide after discharge from the healthcare facility. | A | 96.1% |

| REC 3.6 | The discharge information has to be provided within 24h of discharge to all stakeholders involved with the person's aftercare including. | B | 88.0% |

| REC 3.7 | Liaison with care centres should be made to ensure that referred aftercare has been received. | A | 92.1% |

| REC 3.8 | To promote continuity of care, the care provider should contact follow-up care centres as early as possible, ideally within three days of the discharge. | A | 92.3% |

| REC 3.9 | If the patient is not already under established psychiatric care, the emergency department team should organize the first follow-up visit and provide up to three contacts until follow-up care in the community can be ensured. | B | 88.2% |

| REC 3.10 | Follow-up contact should include at least one face-to-face visit, which, based on patient needs and availability, can be complemented by telephone, videoconference consultations, and home visits. | A | 94.2% |

| REC 3.11 | Follow-up care after a suicidal crisis should include supportive contact, reminders of appointments, invitation to stay in touch, and a continuous discussion of adherence to safety planning and any possible changes require. | A | 92.1% |

| REC 3.12 | When a patient at acute risk of suicide has missed an appointment, the healthcare team should call the patient the same day and, if unreachable, leave a message to propose another appointment. | A | 94.7% |

| REC 3.13 | When a patient with at acute risk of suicide has missed an appointment, the health team should inform their general practitioner. | C | 73.7% |

| REC 3.14 | For patients in suicidal crisis, implementation of brief psychotherapeutic interventions focused on reducing suicide risk is recommended within the first month after discharge. | B | 89.5% |

| REC 3.15 | Long-term treatment with benzodiazepines should be avoided in patients considered at high risk of suicide. | B | 85.5% |

| REC 3.16 | Emergence or worsening of suicidal ideation should be assessed within the first two weeks following the initiation of antidepressant medications. | A | 94.7% |

| REC 3.17 | Lithium salts should be considered to specifically prevent suicidal behaviour in patients with bipolar disorders with a past history of suicide attempt. | A | 94.7% |

Presented in temporal order of care rather than the percentage of agreement. Grades are based on the percentage of combined agreement (agree+somewhat agree). U, unanimous (100%) agreement; A, 90–99% agreement; B, 78–89% agreement; C, 67–77% agreement. Agreement is the highest final agreement in the second round, except from the cases when agreement was higher in the first round, and initial statement was kept instead.

While consensus was generally strong, panellists were divided on the capacity of clinical assessment to predict individual suicide behaviour (SB), aligning with existing research indicating the limitations of current tools for SB prediction.8 Pharmacological approaches were another contentious area, with a lack of consensus on the use of lithium salts in mood disorders to prevent SB (while it was retained for bipolar disorder), clozapine use as a first-line treatment of patients with schizophrenia at high risk of suicide, and use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in patients with a suicidal crisis.

Key recommendationsThe following domains summarize the main areas of agreement. The complete recommendations formulations and quantitative results on the agreement for each recommendation are reflected in Tables 2–4.

Throughout clinical assessment of individuals at risk of and during the suicidal crisisTwelve recommendations regarding the patient assessment reached a consensus (Table 2). Psychiatrists are recommended to assess suicide risk systematically (REC 1.1). We also call for referral to a mental health professional for patients with a history of a suicide attempt in the past year (REC 1.2). Emphasizing comprehensive clinical assessment (REC 1.3), the panellists unanimously agreed that it should encapsulate not just the present suicidal ideation, intent, and preparation (REC 1.4) but also consider the patient's psychiatric, somatic, psychological, and social history (REC 1.7). The panellists also agreed that validated scales could assist clinical judgement but not substitute it and that we should be mindful of potential patient ambivalence or denial (REC 1.5 and 1.6). Prior to decision-making regarding discharge or further psychiatric care, a thorough medical and toxicological assessment should be made (REC 1.8, 1.9, and 1.10). Finally, there was a strong consensus for the involvement of family members or trusted individuals in the assessment process (REC 1.11), with a moderate consensus supporting this engagement even against the patient's will in high-risk scenarios (REC 1.12).

Immediate careFourteen recommendations regarding immediate management achieved substantial consensus (Table 3). The panellists agreed on the importance of involving a trusted person in all patient care phases (REC 2.1) and the need for a comprehensive discussion about hospitalization or intensive outpatient care options (REC 2.2). If the patient has active suicidal ideation or a recent suicide attempt with low insight, involuntary hospitalization can be considered (REC 2.3). It is important to ensure a secure environment and continuously track the patient's psychiatric status and treatment response (REC 2.4, 2.5, and 2.6). Regarding pharmacological interventions, using ketamine or esketamine in depressed patients with active suicidal ideation (REC 2.7) and the concurrent temporary use of a low-dose hypnotic or anxiolytic with antidepressants could be beneficial (REC 2.9). Finally, prior to discharge, it is recommended to provide patients and their trusted individuals with detailed information about their condition and care plan, counsel on limiting the access to lethal means (including fractioned medication dispensing), implement collaborative safety planning (REC 2.11, 2.13, and 2.14), and ensure that the discharge record is comprehensive and includes suicidal history and at least one contact from their social network (REC 2.12).

Long-term approachesWe propose 17 recommendations aimed at improving discharge and post-discharge protocols. We recommend that patients receive proper information regarding follow-up care, necessary prescriptions, and have the contacts of the crisis services and helplines (REC 3.1 and 3.4). Digital and remote caring contact programmes, run by mental health professionals, are encouraged to complement traditional face-to-face care (REC 3.2 and 3.3). We emphasize the continuity of care strategies to overcome non-adherence issues, necessitating timely communication with all relevant stakeholders and ensuring that the patient has received the referred aftercare (REC 3.5–3.8). The ED should arrange the first follow-up visit for patients not under existing psychiatric care, while ensuring the continuation in the community (REC 3.9). These visits should ideally be in-person but can incorporate remote options (REC 3.10). Patients should be consistently encouraged to maintain contact, adhere to safety planning, and promptly reschedule missed appointments, with a proactive reach out to the patient and his or her general practitioner if the patient has missed an appointment (REC 3.11–3.13). Finally, the consensus was reached regarding the need to implement brief psychotherapeutic interventions (REC 3.14) and establish careful pharmacological management, including the use of lithium salts for bipolar disorder patients, avoiding protracted use of benzodiazepines, and regular assessment of patients’ status, especially when starting antidepressants (REC 3.15–3.17).

DiscussionAttending to individuals in suicidal crisis necessitates continuous effort, from evaluation and collaboration with the patient and their social circle to interdisciplinary participation and care continuity. Here, we discuss key recommendations for the assessment and management of individuals in suicidal crisis, from pre- to post-care.

The recommendations that suicide risk assessment should be an integral part of every consultation and that patients with past-year SA history should be referred to mental health specialists align with the principle “prevention is the best intervention”. Indeed, the majority of individuals that died by suicide did it during their first attempt, and those who did not die remained at elevated risk.15 In addition, while suicidal ideation often fluctuates,16 it has been proposed that STB exist in the severity continuum, and suicide prevention might be more successful earlier on. Indeed, when patients are not evaluated, they are more likely to repeat visits for SB.17 Our recommendations also reaffirm that a throughout medical and toxicological assessment should precede psychiatric decisions. While the link between substance use with STB is well established,18,19 individuals presenting to the ED with acute intoxication are less likely to receive a thorough risk evaluation,20 which should not be the case.

Despite our current inability to predict which particular individual will die by suicide,8 the throughout clinical assessment allows us to detect the majority of individuals at high risk, of whom only a small part would eventually die by suicide. Such oversampling can be considered a “wide-net” approach, resulting in interventions for many individuals at elevated risk rather than trying to guess which one of them is the most likely to die by suicide. In the future, a better understanding of the pathophysiology underlying the SB and advancement in data collection, processing and interpretation might help to improve the estimations of STB risk.21,22 For now, there are suicide risk assessment tools, but these should have a supportive rather than substitutive role in the clinical assessment,23 which is grounded in the integration of diagnostic expertise and awareness of risk factors and warning signs.

A complete clinical assessment considers such nuances as ambivalence and denial that can significantly impact interpretation and intervention strategies.24,25 Indeed, around half of the suicide decedents denied SI when questioned in the month before the suicide.25 The difficulty in capturing the SI in clinical interviews is also reflected by the findings that individuals report less SI to clinicians than in self-rated scales and ecologic momentary self-assessments.26,27 Systematically contacting the individual's social circle to collect collateral information is therefore highly recommended.28 The importance of gathering such information is further supported by the consensus regarding the possibility to seek information (but not provide it) from family members, even against the patient's will in high-risk situations. Such a recommendation supports the notion that patient safety might outbalance concerns regarding autonomy and confidentiality in high-risk situations. Ultimately, preventing suicide protects from medical liability when done right,29 but the balance should be carefully weighted within the existing legal framework30 and carefully documented.

The need to balance the individual's autonomy and safety is also crucial during immediate care, with the strong consensus for the need for a secure environment, continuous surveillance, and the possibility of hospitalization, in some cases against the patient's will. STB are linked to impaired decision-making capacity,31 and an individual in crisis might be unable to make fully considered decisions.32 Meanwhile, while SI is the primary clinical factor associated with being hospitalized after seeking help at the ED,33 the utility of hospitalization in suicidal individuals is still debated.34 Notably, suicide rates are elevated during psychiatric hospitalization35 and peak within a week to a month following it.36 However, there is a strong confounding by indication,37 and suicide risk tends to decrease during more extended hospitalizations.38

Appreciation of impaired decision-making during the suicidal crisis has also translated into two interventions with probably the most robust evidence base for their effectiveness: safety planning and counselling on restricting access to lethal means.9,11 They are ideally implemented shortly after the suicidal crisis, with the understanding that the current return to control does not preclude future difficulties. While these interventions are under-implemented,11 EDs that systemically implemented broad screening and safety planning have seen a marked reduction in suicide rates of their patients.39 Notably, since suicide risk remains elevated after a crisis,36 such interventions should be a part of a larger comprehensive and systemic preparation for post-discharge care, also including patient and family psychoeducation on the diagnosis, care plan, warning signs and available resources, which has shown initial promise in aiding to reduce suicide-related symptomatology,40 as well as a plan of the initial pharmacological management (including fractioned dispensing, a pharmacological equivalent to restriction to lethal means, to prevent self-poisoning deaths), and careful documentation, allowing a smooth transition to the long-term care.

Contrary to safety planning, pharmacological approaches emerged as a contentious area, reflecting a general scepticism towards pharmacological treatments in the context of suicidal crisis.41 First, while many individuals with STB suffer from a major depressive disorder42 and may be prescribed antidepressants that reduce suicide risk in the long term,43 suicidal patients tend to respond less well to classic antidepressants in the short-term, and some younger patients might initially have an activation syndrome and even an increased risk of STB.44 To address it, we recommend monitoring suicidal ideation when initiating antidepressants and considering a temporal prescription of low doses of hypnotics or sedatives in young suicidal patients. However, we also call for caution regarding excessive or prolonged use of sedative/hypnotic medications that may increase the risk of STB.45,46

Meanwhile, there is increasing evidence for the rapid antisuicidal effects of ketamine and esketamine.47,48 Notably, the recommendation for using ketamine or esketamine in suicidal crisis only reached consensus after it was amended to consider rather than directly recommend their use, with many experts justifying their reservation by the lack of experience. Given the limited armoire of specific suicide-targeted interventions with immediate effects,41 we propose that they should be considered a bridge for long-term care that frequently needs active patient engagement to be successfully implemented.

A cornerstone of comprehensive care for a patient at risk for suicide is the continuity of care. As mentioned above, the immediate period post-discharge is the highest-risk period.15,36 Poor participation of suicidal individuals in continuing treatment remains troubling,49 and many patients engage in SB shortly after their previous visits to the ED.3 Prompt implementation of follow-up care is associated with improved medication adherence, decreased suicide reattempt risk, and increased healthcare engagement.50 We recommend that the ED team ensures the care while the care in the community is organized, with an assertive, proactive case management approach.51 In addition to the coordinated continuum of traditional care, we also urge for a multi-modal approach that implements other evidence-based interventions, namely the access to suicide crisis lines,52 brief contact interventions that proactively contact the patient via phone, email or letters,51,53 brief psychotherapeutic interventions,54 and sensible pharmacological management, including the use of lithium in individuals with bipolar disorder,55 and limited use of benzodiazepines.56

A graphic representation of key recommendations is in Fig. 2.

How to use and comparison with other guidelinesThe current clinical guidelines are intended to be used by clinicians caring for individuals in suicidal crises. They are not intended for a political or societal-level approach, and numerous effective suicide prevention interventions, such as school-based interventions,57 are out of scope. However, suicide prevention is most likely to be effective if evidenced-based individual and population strategies are combined. The current guidelines are more up-to-date than the previous European guidelines that did not include such relatively new interventions as safety planning.10 They partly overlap but are substantially more comprehensive than previous Dutch Delphi guidelines that proposed eleven quality indicators for suicide prevention.58 Our guidelines also partly overlap with the detailed 420-item Australian guidelines that addressed staffing and training issues but did not consider pharmacological approaches, safety planning and lethal means counselling.59 Finally, possibly the most corresponding American guidelines focused more on the assessment,60 while the current guidelines provide an A-to-Z approach focusing on interventions.

Strengths and limitationsOne of the strengths of this study is its use of the Delphi methodology. By demonstrating an increased degree of consensus, this method enabled us to add recommendations and determine whether our incorporation of feedback was successful in refining the recommendations. The limitations include the possible lack of representation from some countries, possibly due to differences in the participation in the European Psychiatry Association Suicidology section or suicide research. The survey was also conducted in English only. The scope of expertise and experience of the panel might influence the findings. To ensure panel homogeneity and the clinical applicability of the recommendations, only psychiatrists were consulted, which may introduce a degree of bias. It would be advantageous for future research to incorporate perspectives from a broader spectrum of stakeholders engaged in the detection, evaluation, and care of individuals with STB, including, but not be limited to, ED personnel, social workers, psychologists, healthcare managers, and caregivers. Additionally, patient experiences and perspectives are not directly represented. Given that the survey was conducted online – a format typically associated with lower response rates among experts – we oversampled to compensate, expecting a 50% response rate in the initial round and a 20% dropout rate in the subsequent round of consensus development. These expectations were based on previous online Delphi Surveys and guidance from the NIHR Health Technology Assessment.61–63 Although we achieved a final sample of 80 participants in the first round and 56 in the second, the attrition rate between rounds was slightly higher than anticipated, which could be attributed to the survey's relatively large number of items. An additional limitation of this study is the lack of tailored guidelines for patient populations with specialized needs, including children, the elderly, and individuals with severe mental health or substance use conditions. Subsequent initiatives should focus on delineating the specific needs groups, identifying their needs and creating appropriately modified guidelines.

ConclusionsTo conclude, through a Delphi process, a panel of experts formulated 43 recommendations for the assessment, management, and post-discharge care of individuals in suicidal crisis, emphasizing thorough clinical assessments, patient safety, engagement, and continuity of care. Sustained large-scale concurrent implementation of multiple recommendations is crucial to reach tangible results,39 and we call for further efforts focusing on the implementation, feasibility, personnel training, and continuous evaluation of their effectiveness in diverse settings.

FundingThe study was partly supported by an open research grant from Janssen Cilag, which had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interestIn the past five years, PhC, EO and AL have received consulting and travel grants from Jansen Cilag. Other authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

Authors thank all of the panellists who completed the surveys, including their helpful comments. We further thank Anne Pradoura (Foxymed, Paris) for technical support, and for the help with data collection and extraction. We also thank Janssen Cilag for their unconditional research grant that helped support this research.

Abad Iciar, Acciavatti Tiziano, Amad Ali, Apter Alan, Baca Garcia Enrique, Bazals Judith, Baran Anna, Barrigon Maria Luisa, Blasco Fontesilla Hilario, Carballo Juanjo, Cardoner Narcis, Carli Vladimir, Conejero Ismael, Consol Cristiana, Corbo Mariangela, De la Vega Diego, Debien Christophe, Deisenhammer Ebenhard, Delicato Claudia, Fanelli Giuseppe, Fontoulakis Konstantinos, Giner Danier, Giner Lucas, Gmirtowicz Agnieszka, Gohar Sherif, Gramaglia Carla, Grandgenevre Pierre, Guija Jiulio Antonio, Gusmao Ricardo, Herta Dana-Cristina, Hoertel Nicolas, Iglesias Pablo, Igumnov Sergej, Irigoyen-Otinano Maria, Isometsa Erkki, Jesus Catarina, Jimenez-Trevino Luis, Lewin Jona, Lewitzka Ute, Lopez Nacho, Lopez Castroman Jorge, Lupi Matteo, Mamikonyan Aram, Martinez Cortez Mireia, Mendes Coelho Joao, Michaud Laurent, Micheilsen Philip, Mieze Krista, Millan Manolo, Moreno Paula, Nakov Vladimir, Navickas Alvydas, Negaj Nikolaj, Olea Quintela Rebeca, Orsolini Laura, Ovejero Garcia Santiago, Palao Vidal Diego, Perez Moreno Rosario, Plaza Estrade Anna, Pompili Maurizio, Porras-Segovia Alejandro, Purebl Gyorgy, Racetovic Goran, Rancans Elmars, Ruiz Veguilla Miguel, Rutz Wolfgang, Saenz Herrero Margarita, Saiz Lola, Sanz-Aranguez Belen, Sarchiapone Marco, Schneider Barbara, Serafini Giancula, Serretti Alessandro, Soares Anthony, Vaiva Guillaume, Van der Feltz-Cornelis Christina, Voinescu Bogdan, Volpe Umberto, Voros Victor, Zalsman Gil, Zambrano Salvador, Zeppengo Patricia.

Please see a list of the members of the Expert Panel from the EPA Section of Suicidology in Appendix A.