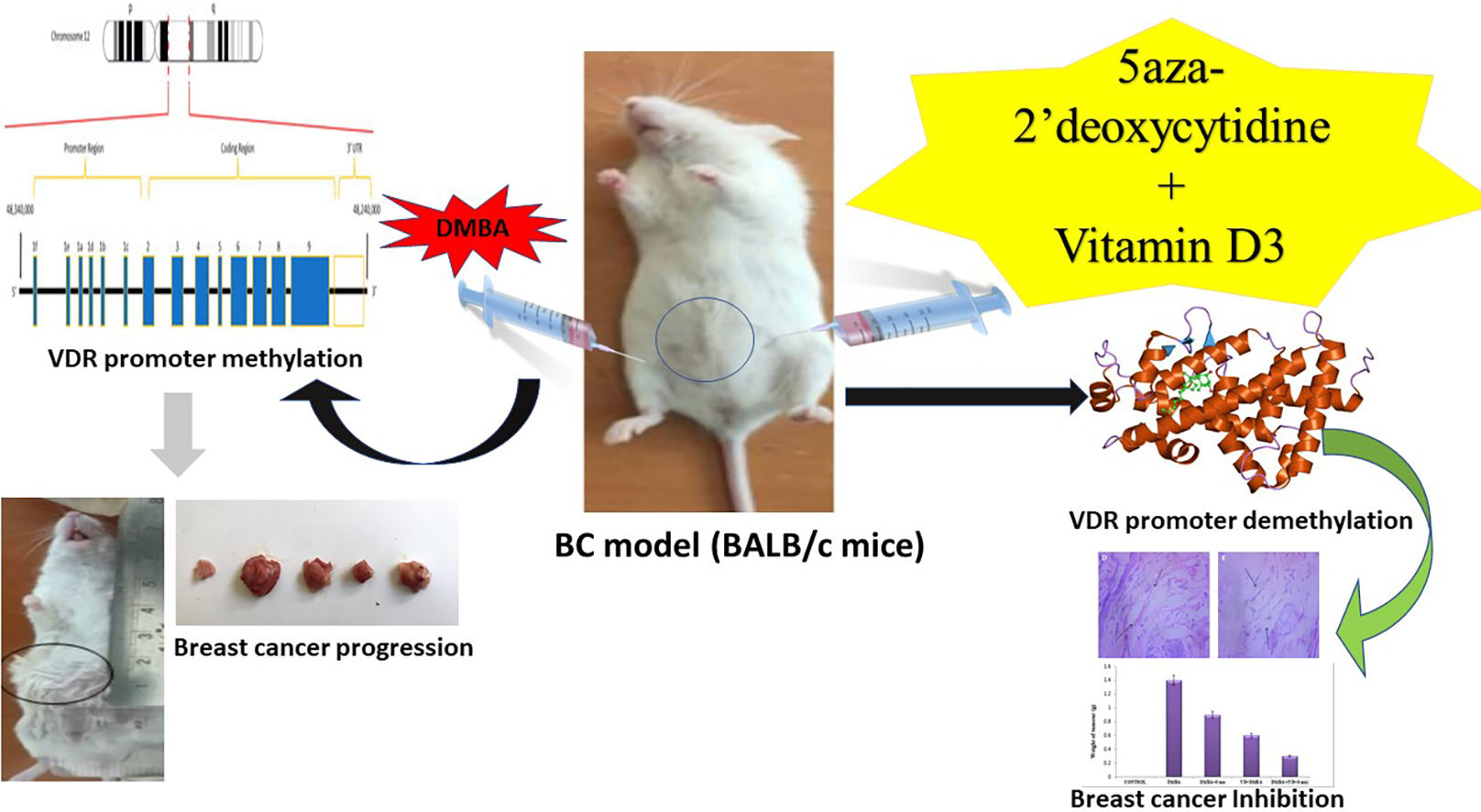

El cáncer de mama (BC) es una enfermedad altamente agresiva, con opciones terapéuticas limitadas. El calcitriol, la forma activa de la vitamina D3, ejerce efectos anticancerígenos a través del receptor de la vitamina D (VDR), aunque a veces su eficacia se ve reducida por la hipermetilación del promotor del VDR. Este estudio investiga el rol de la hipermetilación del promotor del VDR en el cáncer de mama, y evalúa el potencial de 5-Aza-2dC y vitamina D3 para restaurar la función del VDR y mejorar la eficacia terapéutica.

MétodosSe trataron ratones BALB/c con DMBA para inducir la hipermetilación del promotor del VDR. Se analizaron los efectos de 5-Aza-2dC y vitamina D3 en la expresión del VDR, CYP27B1 y CYP24A1, para evaluar su impacto en la señalización de calcitriol y la proliferación del BC.

ResultadosLos ratones tratados con DMBA exhibieron hipermetilación del VDR, incremento de CYP24A1 y reducción de la expresión de VDR y CYP27B1, con crecimiento tumoral significativamente realzado. El tratamiento con 5-Aza-2dC revirtió la hipermetilación del VDR, restauró la expresión del VDR y CYP27B1, y suprimió CYP24A1, causando una reducción del tamaño tumoral y unos niveles más elevados de vitamina D3. El tratamiento previo con vitamina D3 preservó la expresión del VDR y CYP27B1, la reducción de CYP24A1 y la protección frente a la metilación del VDR, reduciendo la proliferación tumoral. El tratamiento combinado con 5-Aza-2dC y vitamina D3 mejoró sinérgicamente la desmetilación del VDR, redujo los niveles de CYP24A1 y vitamina D3, e inhibió significativamente la proliferación del BC, reduciendo el tamaño tumoral.

ConclusiónRevertir la hipermetilación del VDR con 5-Aza-2dC y vitamina D3 ofrece una estrategia prometedora para superar la resistencia al calcitriol y mejorar los resultados terapéuticos en el BC. Esta combinación puede mejorar la eficacia de las terapias basadas en la vitamina D3 en el tratamiento contra el BC.

Breast cancer (BC), the most prevalent and second-leading cause of cancer deaths in women worldwide, constitutes one-fourth of all female cancers.1 Every year, more than 2.3 million new cases are diagnosed.2 In India, BC ranks highest among women, accounting for 28.2% of all malignancies.1 Notably, 95.6% of BC cases are linked to vitamin D deficiency, highlighting the critical role of adequate vitamin D levels in BC.3 Vitamin D3 (1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3), the biologically active form of vitamin D, plays crucial roles in bone metabolism and immune regulation, obtained through sunlight exposure, dietary sources (fatty fish, fortified foods), and supplementation. However, its bioavailability is significantly influenced by multiple factors including age, skin pigmentation, geographic location, and individual absorption capacity.4 As a potent endocrine regulator, vitamin D3 exerts its effects primarily through binding to the VDR, a ligand-activated transcription factor. The activated VDR complex plays a crucial role in regulating cell proliferation and apoptosis, while also promoting cellular differentiation and suppressing inflammation. It further inhibits angiogenesis and metastasis, modulates epigenetic changes, and interacts with key signaling pathways such as Wnt/β-catenin, PI3K/Akt, and NF-κB.5,6 This multifaceted regulatory capacity highlights the critical importance of vitamin D3/VDR signaling in maintaining cellular homeostasis and its potential implications in disease prevention and treatment.7

In BC cells, the VDR gene promoter is extensively methylated at CpG islands, where cytosine is followed by guanine in a linear base sequence from 5′ to 3’direction.8 Essentially, it is an epigenetic mechanism wherein methyl groups are added to cytosine at the C5 position, forming 5-methylcytosine. This alteration is facilitated by the overexpression of DNA methyltransferase (DNMT), specifically DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B. Notably, hypermethylation of the VDR gene promoter hampers its functionality, inhibiting vitamin D3 from binding to VDR. This molecular alteration is associated with the development of a spectrum of diseases including various types of cancer such as BC, adrenocortical carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and colorectal cancer, autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, infectious diseases like tuberculosis and HIV.9

The use of demethylating agents to mitigate the VDR promoter hypermethylation will facilitate the restoration of VDR gene expression. This process not only restores normal gene function but also offers a potential therapeutic pathway for managing various diseases including BC.10 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-Aza-2dC) is a nucleoside-based DNA methyltransferase inhibitor that promotes DNA demethylation.11 5-Aza-2dC irreversibly inhibits DNA methyltransferases, depleting them and causing passive DNA demethylation, which can reactivate silenced genes.12 This study investigates DMBA-induced VDR promoter hypermethylation in BALB/c mice and explores 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine-mediated demethylation in BC. We examine the role of vitamin D3/VDR in mammary cell growth and differentiation, along with the combined effects of vitamin D3 and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine on BC proliferation. Our findings aim to clarify the link between VDR methylation status and therapeutic responses in BC progression.

Materials and methodsChemicals and reagentsThe chemicals 7, 12-Dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA), 5-aza 2’deoxycytidine, Ketamine hydrochloride, Xylazine hydrochloride, Isoflurane, and Corn oil were obtained from Sigma Aldrich. Ethylene Diamine Tetra Acetic acid (EDTA), Sodium hydroxide (NaOH), Isopropyl alcohol (IPA), Phosphate buffered saline (PBS), hematoxylin, eosin, and Glycerine were purchased from HiMedia. Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) was acquired from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd.

Experimental designA total of 30 female BALB/c mice (6 weeks old, 18–22 g) were housed in groups of six under controlled conditions (23 ± 2 °C, 12-h light–dark cycle) with ad libitum access to standard pellets and autoclaved RO water (average intake: 8–10 g food and 6 mL water/day). Mice were randomly divided into five groups (n = 6): Group 1 (healthy control) received 0.4 mL saline for 20 weeks; Group 2 received intraperitoneal DMBA (1 mg/mouse/week) for 20 weeks to induce breast cancer; Group 3 received DMBA for 12 weeks, followed by 5-aza-2dC (0.2 mg/kg, IP) for 8 weeks; Group 4 received oral vitamin D3 (5 μg/kg) for 8 weeks, then DMBA for 12 weeks; Group 5 received DMBA for 12 weeks followed by combined vitamin D3 and 5-aza-2dC treatment for 8 weeks. Dosages and treatment schedules were based on established protocols from prior studies,13–16

Animal body weight and tumor assessmentInitial body weights of all mice were recorded using an electronic balance (Supplementary Fig. 1) and used to calculate treatment dosages. Weights were monitored weekly throughout the study. On day 150, post-euthanasia, tumors were excised, and their dimensions were measured using a ruler (Supplementary Fig. 2). Tumor volume was calculated using the formula: Volume = Length × (Width)2 × 0.52.17 Tumor weights were then recorded in milligrams using an electronic balance (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Histological evaluationFor histological evaluation, mice were sedated with 2.5% isoflurane and euthanized by decapitation. Breast tissue was collected post-euthanasia, washed with 1X PBS, and fixed in 10% formalin. The tissue was dehydrated in graded isopropanol (70–100%), cleared in xylene, and infiltrated with paraffin wax at 55 °C before embedding. Sections (5 μm) were cut using a rotary microtome, floated on 60 °C water, and mounted on egg albumin-glycerin-coated slides. Slides were dewaxed, treated with xylene and IPA, and stained with hematoxylin followed by acid alcohol differentiation, rinsed, and counterstained with eosin. After dehydration and clearing, slides were mounted with DPX and examined under a bright-field microscope to assess cellular morphology and tissue architecture.

Methylation-specific PCRTo assess VDR promoter methylation in control and treated breast tissues of BALB/c mice, genomic DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) and quantified via NanoDrop spectrophotometry. Two micrograms of DNA were bisulfite-converted using the Epitect Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen) to distinguish between methylated and unmethylated cytosines. Methylation-specific PCR (MSP) was performed using primers targeting CpG sites in the VDR promoter, designed with MethPrimer. Each 25 μL reaction contained 20 ng of bisulfite-converted DNA, 10 Ll of PCR Master Mix, and 0.5 μM of each primer (supplementary Table 1). PCR conditions included initial denaturation at 95 °C (10 min), followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C (30 s), 58–60 °C (30 s), and 72 °C (45 s), with a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. PCR products were resolved on a 2% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized under UV to determine VDR promoter methylation status.

Real-time PCR analysisTotal RNA was extracted from 100 mg of breast tissue using TRIzol reagent, followed by phase separation with chloroform and RNA precipitation with isopropyl alcohol. The RNA pellet was washed with 75% ethanol, air-dried, and resuspended in RNase-free water. cDNA was synthesized using a mix of template RNA, Oligo dT, random primers, dNTPs, RNase inhibitor, and PrimeScript RT enzyme, with reverse transcription at 25 °C (10 min), 50 °C (60 min), and 70 °C (10 min). Quantitative PCR was performed in 20 μL reactions using SYBR Green I Master Mix, 2 μL cDNA, and 0.5 μM gene-specific primers (CYP27B1, CYP24A1, and β-actin). Thermocycling involved 40 cycles of 95 °C (15 s), 58–60 °C (30 s), and 72 °C (30 s). Gene expression was quantified using the 2(−ΔΔCt) method with β-actin as the internal control, and fold changes were calculated relative to the control group.

Serum vitamin D3 analysis in miceVitamin D3 levels were measured using the Trust Well Vitamin D ELISA kit. Serum samples from BALB/c mice (10 μL), along with calibrators and controls, were added to designated microplate wells, followed by 100 μL of enzyme solution. After mixing and sealing, plates were incubated at room temperature (22–28 °C) for 45 min. Wells were washed twice with 350 μL of working wash buffer. Then, 100 μL of TMB substrate was added and incubated in the dark for 15 min. The reaction was stopped with 50 μL of stop solution, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader, with 620–690 nm as a reference wavelength for result optimization.

Statistical analysisData were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (v8.0) and expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Paired t-tests were used for within-group comparisons, while unpaired t-tests or one-way ANOVA were applied for between-group analyses. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ResultsImpact of DMBA, 5-Aza-2dC, and vitamin D3 on body weight and tumor development in BALB/c miceOver the 150-day study, body weight and tumor development were monitored across five treatment groups (Fig. 1). Control mice showed steady weight gain, while DMBA-induced groups experienced weight loss due to tumor burden. However, treatment with 5-Aza-2dC or vitamin D3 partially restored body weight, with the combined treatment yielding the most significant weight gain, suggesting a protective, synergistic effect.

Tumors appeared as visible mammary lumps in DMBA-treated mice. On day 150, tumor size, volume, and weight were assessed (Fig. 2a–c). The DMBA control group exhibited the largest tumors (2363 ± 6.4 mm3; 1.4 ± 0.08 g). 5-Aza-2dC treatment reduced tumor volume and weight (1788 ± 6.8 mm3; 0.9 ± 0.05 g), while vitamin D3 pre-treatment showed further reduction (1289 ± 7.8 mm3; 0.6 ± 0.04 g). Notably, the combined treatment group had the smallest tumors (489 ± 7.8 mm3; 0.3 ± 0.07 g), indicating strong anti-tumor effects, likely via VDR demethylation and reactivation.

(a) Image of DMBA-induced breast tumor in control and treated BC groups shows size variations in tumor. (A) Control, (B) DMBA control, (C) DMBA + 5-Aza-2dC, (D) DMBA + Vitamin D3 + 5-Aza-2dC, (E) vitamin D3 + DMBA. (b) Graphical representation of the average of tumor volume measurement between five groups at the end of the study with P value <0.05 (ANOVA) indicates a highly significant difference among the means of the groups. This suggests that there is a substantial variation in tumor volume across the different groups bearing BC. (c) Tumor weight of BALB/c mice. Data represent the mean of five groups with ±SEM. The calculated P value <0.05 (ANOVA) indicates the significant changes in the tumor volume suggesting the effective treatment of vitamin D and 5 Aza 2,dc in BMBA-induced BC.

Histological analysis of breast tissues at the end of the study revealed distinct morphological changes across groups (Fig. 3a–e). The healthy control group showed normal ductal and acinar architecture with intact nipple and areola regions. In contrast, the DMBA-induced group exhibited neoplastic ductal epithelial cells with hyperchromasia, high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, and pleomorphism, indicative of well-differentiated breast cancer. Treatment with 5-Aza-2dC significantly reduced tumor cell presence, showing the absence of glandular structures and prominent fibrosis, supporting VDR gene demethylation. In the vitamin D3 pretreated group, inflammatory granulation tissue replaced normal architecture, with no ducts or acini observed. Notably, the combined treatment group (DMBA + 5-Aza-2dC + vitamin D3) showed restoration of near-normal tissue with non-neoplastic acini surrounded by fibrous tissue, and normal-appearing nipple and areola, with no residual tumor detected.

(A) Normal breast tissue. (B) BC induced by DMBA the ductal structures containing neoplastic ductal epithelial, hyperchromasia, nuclear cytoplasmic ratio. (C) Significant reduction in tumor cell, fibrosis was evident. (D) Reduced BC marked areas of inflammatory granulation. (E) Single-layered non-neoplastic cells with nipple and areola area appeared normal.

Methylation-specific PCR revealed hypermethylation of the VDR promoter in breast tissues of DMBA-treated BALB/c mice. Treatment with 5-Aza-2dC significantly reduced this methylation, and the combined use of 5-Aza-2dC and vitamin D3 further enhanced demethylation (Fig. 4a). Pretreatment with vitamin D3 alone also attenuated DMBA-induced methylation, indicating its protective role. Correspondingly, gene expression analysis via real-time PCR revealed that DMBA increased the expression of CYP24A1 (which inactivates vitamin D) by 1.5-fold (p < 0.001) and decreased VDR and CYP27B1 (which activates vitamin D) expression to 0.3-fold relative to healthy controls (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4b). Treatment with 5-Aza-2dC lowered CYP24A1 expression to 0.5-fold and elevated VDR and CYP27B1 expression to 1.2-fold compared to the DMBA group (p < 0.001). Vitamin D3 pretreatment maintained VDR and CYP27B1 expression near control levels and reduced CYP24A1 expression by 40% (p < 0.001). The combined treatment further enhanced this effect, increasing VDR and CYP27B1 expression by 1.8-fold and reducing CYP24A1 expression to 0.3-fold compared to the DMBA group (p < 0.001). These findings highlight the therapeutic potential of VDR demethylation in restoring the vitamin D signaling pathway and inhibiting breast cancer development, particularly through a synergistic effect of 5-Aza-2dC and vitamin D3.

(a) Gel electrophoresis images depict the methylated VDR, and unmethylated VDR genes obtained from methylation-specific PCR analysis. (b) Gene expression analysis was conducted using Real-Time PCR to measure the mRNA levels of VDR, CYP27B1, and CYP24A1. P value <0.05 indicates significant differences.

The variation in serum vitamin D3 levels among the experimental groups at the end of the study is summarized in Fig. 5. The control group (Group I) showed an average level of 15.7 ± 0.2 ng/ml (p = 0.05). In contrast, the DMBA-only group (Group II) exhibited a significant reduction to 13.7 ± 0.1 ng/ml (p < 0.05), likely due to breast cancer development. Group III, treated with DMBA and 5-Aza-2dC, showed a moderate increase to 14.6 ± 0.5 ng/ml (p = 0.05), attributed to the demethylating action of 5-Aza-2dC on the VDR promoter. Group IV, which received vitamin D3 supplementation with DMBA, recorded a higher level of 15.9 ± 0.8 ng/ml (p = 0.05). The highest vitamin D3 concentration was observed in Group V (DMBA + 5-Aza-2dC + vitamin D3), reaching 16.8 ± 0.1 ng/ml (p < 0.05), indicating a synergistic effect of the combined treatment.

Vitamin D3 concentration between 5 treatment groups showing an elevated level of vitamin D3 in group V. A p-value of <0.05 (ANOVA) indicates a highly significant difference in Vitamin D3 levels among the five groups, suggesting that the treatment has a substantial impact on the Vitamin D3 levels.

Advancements in the Human Genome Project have highlighted epigenetics' crucial role in gene regulation, disease development, and biological behavior. Epigenetic mechanisms like DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA influence gene expression without changing the DNA sequence.18 DNA methylation, in particular, is key in tumorigenesis and cancer diagnosis. In several cancers, including breast cancer (BC), increased VDR methylation silences the VDR gene, impairing its antiproliferative function.19–22 In BC, VDR promoter hypermethylation is significantly higher (65%) compared to normal breast tissue (15%),10 leading to vitamin D3 insensitivity.

This study evaluated the role of vitamin D3 in mammary gland differentiation and its anticancer potential via calcitriol. Following 12 weeks of DMBA induction and 8 weeks of treatment, variations in body weight, tumor volume, and tumor weight reflected treatment efficacy and the influence of VDR methylation. The DMBA-only group exhibited the largest tumors (2363 mm3, 1.4 g), while the combination group (5-Aza-2dC + vitamin D3) showed a significant reduction (489 mm3, 0.3 g). Treated groups also demonstrated improved weight gain, suggesting reduced DMBA toxicity. These results are consistent with prior findings—tumor volume of 1800 mm3 using 4T1 cells,23 and 430 mm3 using DMBA in Charles Foster rats.24 Overall, this supports the therapeutic potential of combining 5-Aza-2dC and vitamin D3 to reduce tumor burden and overcome resistance in DMBA-induced BC.

Histopathological evaluation supported the therapeutic potential of the treatments. DMBA-induced breast cancer led to pronounced neoplastic alterations, while 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine treatment reduced tumor presence and promoted tissue remodeling, likely through VDR gene demethylation and restored vitamin D/VDR signaling.25 The inflammatory changes in the vitamin D3 pretreated group suggest early tumor development with enhanced resistance to DMBA toxicity. Notably, the combined treatment group displayed nearly normal tissue structure, indicating superior efficacy in reversing DMBA-induced malignancy. These findings underscore the role of VDR demethylation, enhanced by vitamin D3, in mitigating tumor progression.

The combination of vitamin D3 and 5-Aza-2dC offers a promising therapeutic strategy for BC by targeting key molecular mechanisms involved in tumor progression. VDR methylation and downregulation of CYP27B1 reduce the activation of vitamin D3, impairing its tumor-suppressive effects. 5-Aza-2dC, a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor, restores VDR expression by demethylating the VDR promoter, reactivating the vitamin D3 signaling pathway.9 Moreover, 5-Aza-2dC downregulates CYP24A1, preventing the inactivation of calcitriol and enhancing its anticancer properties, such as inhibiting cell proliferation, inducing apoptosis, and reducing metastasis.

Vitamin D3 not only restores VDR expression but also stabilizes the demethylated state of the VDR promoter, ensuring sustained transcriptional activation of VDR and other downstream tumor-suppressive genes.26 This creates a positive feedback loop, enhancing the therapeutic effects and preventing re-methylation of the VDR promoter. By simultaneously targeting both epigenetic silencing and vitamin D3 signaling, this combination therapy effectively overcomes common resistance mechanisms in cancer cells.

Additionally, the synergy between 5-Aza-2dC and vitamin D3 offers a multi-faceted approach to tumor control. Beyond reactivating VDR expression, this treatment may enhance the immune response, regulate cell cycle progression, and inhibit angiogenesis, all of which contribute to more effective tumor suppression.27,28 The synergistic effect of 5-Aza-2dC and vitamin D3 supports clinical trials in neoadjuvant or metastatic settings. Given that 5-Aza-2dC (decitabine) is FDA-approved for myelodysplastic syndromes,29 it’s repurposing for BC is feasible. Future research should focus on optimizing dosing and exploring non-invasive monitoring through circulating tumor DNA or PET imaging to track treatment response.

ConclusionIn conclusion, our study highlights the therapeutic potential of combining vitamin D3 and 5-Aza-2dC in counteracting DMBA-induced breast cancer in BALB/c mice. The combined treatment demonstrated promising outcomes, including significant inhibition of tumor growth and reversal of VDR promoter hypermethylation. The demethylating agent 5-Aza-2dC, known to inhibit DNA methyltransferases, played a key role in inducing passive demethylation and reactivating the silenced VDR gene. Vitamin D3 enhanced the therapeutic outcome by activating the re-expressed VDR and promoting downstream vitamin D3/VDR-mediated anti-tumor signaling. Overall, this study provides valuable insights into the epigenetic regulation of breast cancer progression and suggests that the combination of 5-Aza-2dC and vitamin D3 holds promise as a targeted therapeutic strategy. Future research should focus on optimizing this combination and validating its efficacy in clinical settings to support its potential in breast cancer management.

Informed consentInformed consent was not required as the study did not involve any individual personal data or identifiable images.

Ethical approvalThe animal experiments were ethically sanctioned by the Institutional Animal Ethical Committee of Bharathiar University, Coimbatore 641 046, with approval reference BU/BT/IAEC/2022/2-10. The Applied Research Ethics National Association guidelines were followed to ensure the welfare of animals in the study.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

The authors would like to thank Bharathiar University, Department of Biochemistry, for providing facilities to carry out the research.