This study aims to determine the guiding principles for the implementation of peer support programmes in Portugal.

Materials and methodsThe study was divided in two phases. In the first phase a systematic review of 112 papers indexed in ISI and EBSCO databases (2001–2012) was conducted. In the second phase clinicians, researchers, and people with psychiatric disabilities were invited to take part in a two-round online survey based on the Delphi process to rate the importance of statements generated from the systematic review. Data were analysed with NVIVO 9 and SPSS 19.

ResultsDuring the Delphi round 72 experts were contacted, 44 participated in the second round. A consensus was achieved on major statements, with 84% of the sentences obtaining a consensus and eight key recommendations covering goals of peer support, selection of peer supporters, training and accreditation, role of mental health professionals, role of peer supporters, access to peer supporters, looking after peer supporters, and programme evaluation were based on these statements.

ConclusionsUse of peer support for mental heath problems is still underexplored and surrounded by some controversy and ambiguity. However, its organisation and proper monitoring appears to enhance the quality of life and social inclusion of people with mental illness. This highlights the importance of conducting studies that increase our knowledge of these programmes and determining guidelines for their implementation. This national consensus may be used as a starting point for the design and implementation of peer support programmes in mental health organisations.

Este estudio tiene como objetivo determinar los principios orientadores para la implementación de programas de apoyo entre personas con problemas de salud mental en Portugal.

Material y métodosEste estudio ha sido dividido en dos fases. El primer paso se realizó una revisión sistemática de 112 artículos indexados en las bases de datos del ISI y EBSCO (2001–2012). En la segunda fase, se llevó a cabo un panel Delphi en dos rondas formado por profesionales, investigadores y personas con problemas de salud mental, con el objetivo de analizar las afirmaciones generadas por la revisión sistemática previa. Los datos fueron analizados con NVIVO’9 y SPSS’19.

ResultadosDurante la ronda Delphi participaron inicialmente 72 expertos, de los cuales 44 participaron en la segunda ronda. Se alcanzó un consenso del 84% sobre las principales afirmaciones. A partir de estos resultados, se destacan ocho ámbitos principales que cubren las siguientes áreas: objetivos de apoyo de los pares, selección de los proveedores de apoyo, capacitación y acreditación, papel de los profesionales de salud mental, papel de los proveedores de apoyo, acceso a los proveedores de apoyo, cuidado de los proveedores de apoyo, y programa de evaluación.

ConclusionesEl apoyo entre pares aplicado a la enfermedad mental esta todavía poco explorado y rodeado de una cierta controversia y ambigüedad. Sin embargo, su organización y un control adecuado parece mejorar la calidad de vida y la inclusión social de las personas con enfermedad mental. Este hecho demuestra la importancia de realizar estudios para aumentar nuestro conocimiento acerca de estos programas y determinar las directrices para su aplicación. Este consenso nacional se puede utilizar como punto de partida para el diseño e implementación de programas de apoyo entre pares en las organizaciones de salud mental.

The movement to change to the mental health care system, often referred to as the deinstitutionalisation movement, was started in the mid-1970s by people with mental health problems.1,2 This movement led to the emergence of a new intervention paradigm, mainly focused on the functionality and social integration of people who experience mental health problems and also aimed to demystify mental health problems and widespread myths about sufferers and improve understanding of the nature of chronic mental health problems.1,2

Countries like the United States of America (USA), Australia, Canada, and various countries in Europe have developed new interventions and employed peer workers in different settings.3–5 Portugal and Spain lag behind these countries in terms of this practice, but the issue is beginning to be discussed. In Portugal, a document produced by the Advisory Commission for Users and Career Participation (CCPUC; Comissão Consultiva para a Participação de Utentes e Cuidadores) highlighted the need for peer support groups based on the benefits such groups have for people recovering from mental health problems, including, the providers of the service, for professionals and for the mental health care system.6 In Spain, the need to integrate people with mental health problems into society and respond appropriately and efficiently to their needs has been recognised. One of the measures proposed to support the integration of people with mental health problems is the development of mutual-help and self-help groups.7 The National Mental Health Plan of Portugal and Spain also highlighted the need to integrate people who experience mental health problems by providing supported employment, education, housing, social participation, etc. The National Plans suggested that the focus should be users of mental health services and on reducing the stigma attached to mental health problems. The importance of developing and implementing evidence-based practice that contributes to the promotion of mental health and prevention of mental health problems was also emphasised; it was suggested that this might reduce the stigma of mental health problems and reduce discrimination against mental health service users. One of the most important measures referred to was the promotion of self-help groups, social support and community networks.8,9 It is therefore important to develop guidelines for peer support, which will facilitate the creation of peer support groups for people with mental health problems and demystify mental health problems. There have been several studies in the field of mental health on guidelines for peer support. Creamer and colleagues10 researched guidelines for peer support in high-risk organisations in Australia. Repper5 reviewed publications relating to peer support and analysed the basic concepts underlying this practice. The International Association of Peer Supporters (iNAPS) created national guidelines for the use of peer support in the USA.11 Campos et al.12 conducted the first study about guidelines for this practice in a Portuguese context. To date there has been no published research on guidelines for peer support for mental health problems in a Spanish population.

The spread of studies about peer support led to the belief that people with mental health problems can play a significant role in society. It is assumed that due to their personal experiences, mental health service users will empathise with individuals experiencing mental health problems and be able to help them understand mental health problems and develop new ways of managing them.2,13 Peer supporters or peer specialists have an empathetic understanding and can draw on shared experience when working with peers.14 In 1990 the World Health Organisation emphasised the importance of actively involving mental health service users in their care.15

Over the years peer support has become an important component of mental health services.16 Gartner and Riessman17 defined peer support as social and emotional support offered to each other or arranged for people with mental health problems by other people with similar health conditions in order to obtain a desired personal and social change. Mead et al.18 considered peer support “a system of giving and receiving help founded on key principles of respect, shared responsibility, and mutual agreement of what is helpful” (p135). Peer support reinforces a culture of health, capacity, functionality and the positive aspects of the individual, rather than the disease, symptoms and problems.18,19 Peer support can be part of a model of mental health treatment that promotes wellness and recovery19–21 and it can play a decisive role in the recovery of individuals, because the support provided is based on personal experience, rather than professional knowledge.19 The concept of recovery has been defined in several ways over the past 15 years and the core elements include: rediscovery of hope and meaning; overcoming the stigma associated with mental health problems and regaining control over one's life.22 In the past decade, several epidemiological studies showed that improvement in symptoms and social behaviour is possible for a substantial proportion of people with experience of mental health problems.23

The available evidence suggests that services should be organised around the concept of recovery; services, including peer support services, should reflect the four core values of recovery. These core values include person orientation, person involvement, self-determination and potential for growth.22

A review of the literature suggests that there are three broad categories of peer-delivered intervention: naturally occurring mutual support, participation in peer-run programmes and the use of mental health service users as providers of services and support.1,16,19,24

Natural mutual support is the most basic form of peer support. It is a voluntary support process, which aims to solve common problems or shared concerns. In peer-run programmes service users manage the organisation and decide how support is provided. Peer-run support programmes were created with the aim of becoming an alternative to the formal mental health system and providing activities as supplement or in addition to the peer support.1,2,19 In both these forms of peer support, the relationship is mutual, both parties give and receive support, and the emphasis is on sharing experience and mutual understanding.1,2,19

In peer support programmes where service users are also providers, peers are trained and employed by the traditional mental health services. In this third form of peer support, the relationship is more asymmetric, involving at least one service provider or supporter and a user who receives this support. The fact that peer providers are employed by mental health services and are at a more advanced stage of recovery, can affect the reciprocity of interactions, emphasising the asymmetric, unequal nature of this type of peer support.1,2,19

Generally interventions for people experiencing mental health problems focus on improving quality of life and well-being, encouraging social participation and helping the individual to regain autonomy.25 Recent studies in several countries have found evidence that peer support is as an effective intervention26 that promotes empowerment and improves of quality of life and social participation for both users and providers.16 Several studies in countries including Canada, Scotland and Australia have reported positive results including reductions in admissions and readmissions to hospital, reductions in the use of emergency services, lower costs and high levels of satisfaction.4 In a broader sense published evidence suggests that peer support has widespread benefits for peer supporters, for users who receive this support and for the organisations where providers of peer support work.5,21,27,28

In recent years there has been an evolution and a large expansion of peer support services focused on the recovery of individuals with mental health problems.29,30 This reflects a recognition that the experience of recovery of people with similar conditions can be an important source of support and knowledge for others facing similar mental health problems.23

Despite these promising results, use of peer support in mental health is still unusual, and there is some ambiguity and heterogeneity in models of the organisation and delivery. The available evidence suggests that formal peer support programmes should have: a defined role for peer supporters; access to proper training, support and supervision for peer supporters; training and support for staff to ensure that peer supporters are fully integrated into the team and can function effectively.21 In Portugal and some other countries of South Europe, peer support is an almost nonexistent practice; but it is beginning to be implemented. Given the emphasis on developing good practice guidelines in different domains of healthcare31 it is important that we develop appropriate guidelines for the implementation of peer support programmes. This study aimed to develop a set of guidelines for implementing peer support programmes in the Portuguese psychiatry and mental health system.

Materials and methodsLiterature reviewThe ISI (Web of Science) and EBSCO (Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection; Medline) electronic databases were searched using the exact phrase “mental illness” or “mental health” or “psychiatric disability” and “peer support” or “mutual support” or “self-help groups” or “consumer as providers” or “peer-run services” or “peer-run programmes”. In Medline following Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were used: “mental disorders” or “mental health” or “mental health services” and “self-help groups” or “social support” or “peer support”. The terms were searched as “topics” in ISI, and in “all the fields” in EBSCO. The searches began in May 2012 and were updated regularly until January 2014.

The computerised database search revealed 1189 articles. Inclusion criteria for the studies were: English-language research articles (published between 2001 and December 2013); full text articles; studies of adult populations with psychiatric conditions. Studies of peer support in drug abuse, peer support related to physical illness or to family or caregivers and repeated articles were all excluded.

Titles and abstracts were reviewed by two of the authors to exclude irrelevant or ineligible papers. Each reviewer then analysed the full text of the remaining articles to decide their eligibility. A third reviewer resolved discrepancies during a consensus discussion. A final group of one hundred and twelve documents was obtained and analysed using NVIVO 9.

Delphi expert consensus processA two-round online survey based on Delphi methodology and on a study conducted by the Australian Centre of Posttraumatic Mental Health32 was conducted in addition to the systematic review. Questions were grouped into four main categories: the goals, definition and principles of peer support; training and supervision of providers; models and services provided and the evaluation and effectiveness of peer support. The panel was recruited by the Advisory Commission for Users and Career Participation (CCPUC – Comissão Consultiva para a Participação de Utentes e Cuidadores) of the National Programme for Mental Health.

An email was sent to 20 Portuguese psychosocial rehabilitation organisations, a representative sample of the organisations working in Portugal. Each organisation was asked to invite at least two employees (mental health professionals, researchers and others) and two individuals with experience of mental health problems to answer the questionnaire. Ninety-six individuals were contacted and invited to participate by answering an online questionnaire. The questionnaire asked participants to rate their agreement with various statements using a nine-point Likert scale (1=completely disagree; 5=neutral; 9=completely agree). Participants were also given the opportunity to provide comments on each statement. A score of less than 3 was considered as disagreement with the relevant statement, a score between 4 and 6 inclusive was considered neutral and a score greater than 6 constituted agreement. A statement was considered to have achieved consensus when the frequency of agreement or disagreement exceeded 70%.32,33 The second round of the survey included only the statements that failed to achieve consensus during first round.

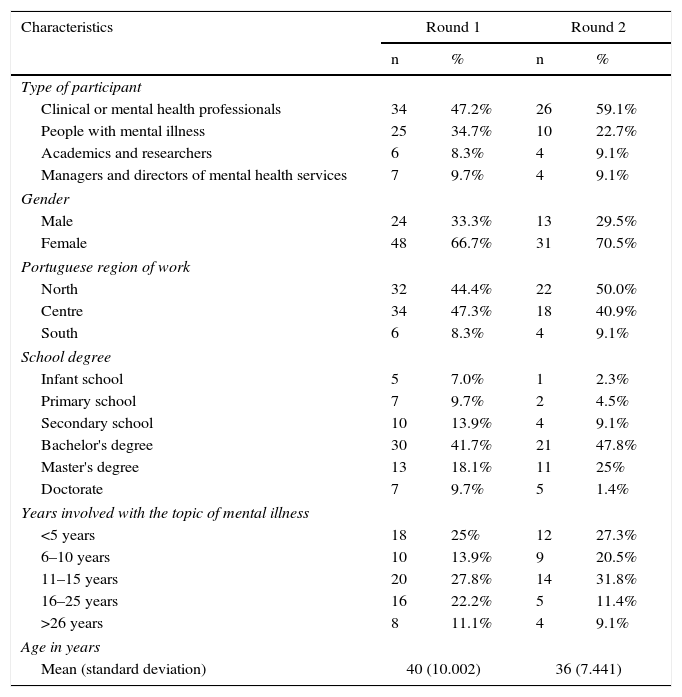

The first round sample consisted of 72 participants and the second round of 44 participants (clinicians, researchers and people with psychiatric conditions). Details of the sample are given in Table 1. Statistical data analysis was performed using SPSS 19.

Characteristics of the sample.

| Characteristics | Round 1 | Round 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Type of participant | ||||

| Clinical or mental health professionals | 34 | 47.2% | 26 | 59.1% |

| People with mental illness | 25 | 34.7% | 10 | 22.7% |

| Academics and researchers | 6 | 8.3% | 4 | 9.1% |

| Managers and directors of mental health services | 7 | 9.7% | 4 | 9.1% |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 24 | 33.3% | 13 | 29.5% |

| Female | 48 | 66.7% | 31 | 70.5% |

| Portuguese region of work | ||||

| North | 32 | 44.4% | 22 | 50.0% |

| Centre | 34 | 47.3% | 18 | 40.9% |

| South | 6 | 8.3% | 4 | 9.1% |

| School degree | ||||

| Infant school | 5 | 7.0% | 1 | 2.3% |

| Primary school | 7 | 9.7% | 2 | 4.5% |

| Secondary school | 10 | 13.9% | 4 | 9.1% |

| Bachelor's degree | 30 | 41.7% | 21 | 47.8% |

| Master's degree | 13 | 18.1% | 11 | 25% |

| Doctorate | 7 | 9.7% | 5 | 1.4% |

| Years involved with the topic of mental illness | ||||

| <5 years | 18 | 25% | 12 | 27.3% |

| 6–10 years | 10 | 13.9% | 9 | 20.5% |

| 11–15 years | 20 | 27.8% | 14 | 31.8% |

| 16–25 years | 16 | 22.2% | 5 | 11.4% |

| >26 years | 8 | 11.1% | 4 | 9.1% |

| Age in years | ||||

| Mean (standard deviation) | 40 (10.002) | 36 (7.441) | ||

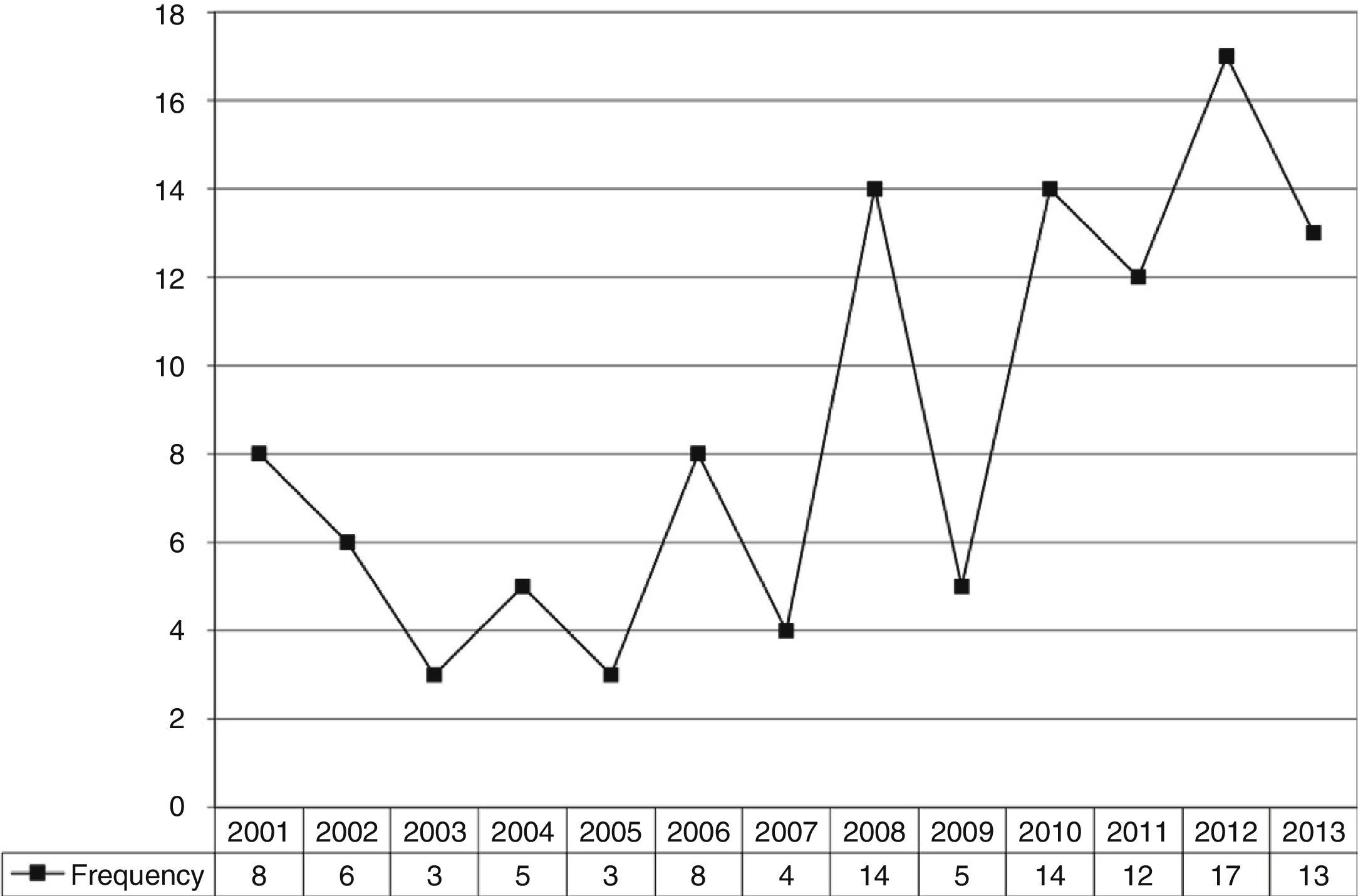

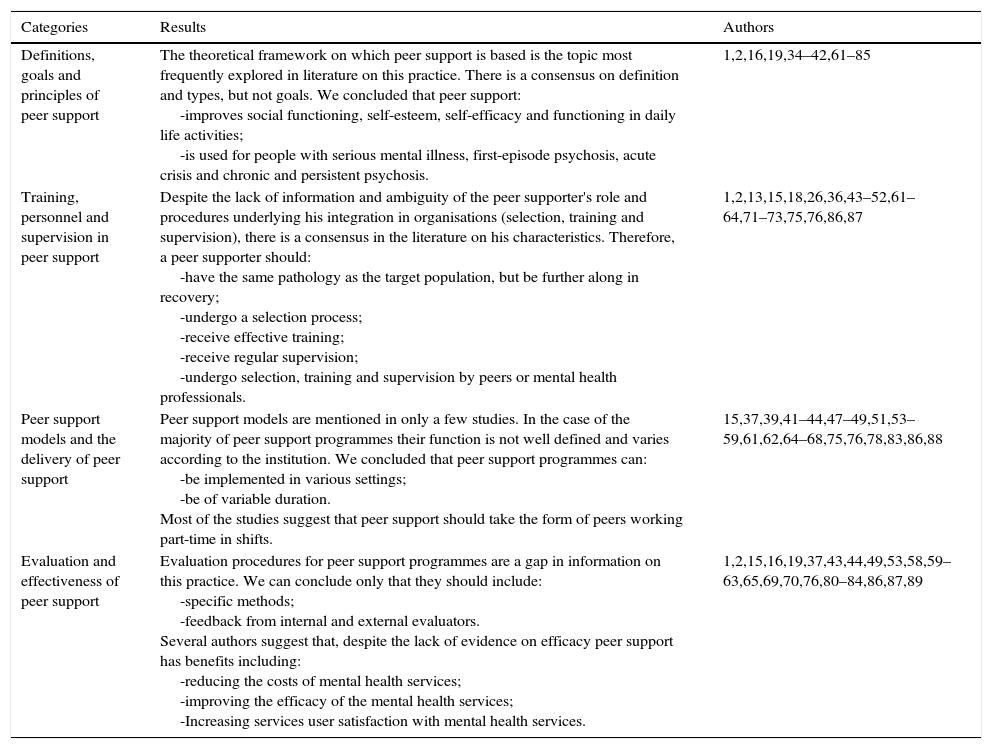

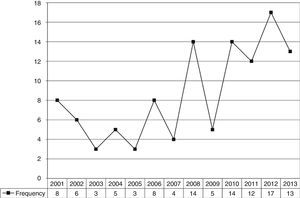

Nuclear primary and secondary order categories related to peer support should be highlighted: characterisation (definition, types, objectives and target population); peer supporter (characteristics, selection process, training and supervision); practices (models, local, contact phase and programmes); and efficacy (empirical and theoretical studies). These dimensions emerged from the literature analysed. The categories listed in Table 2 were developed from the major themes highlighted in the questionnaire. We observed that the number of publications on this subject has increased over the last 10 years (Fig. 1). The main results of the literature review with reference to these categories are highlighted in Table 2.

Results of the literature review.

| Categories | Results | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| Definitions, goals and principles of peer support | The theoretical framework on which peer support is based is the topic most frequently explored in literature on this practice. There is a consensus on definition and types, but not goals. We concluded that peer support: -improves social functioning, self-esteem, self-efficacy and functioning in daily life activities; -is used for people with serious mental illness, first-episode psychosis, acute crisis and chronic and persistent psychosis. | 1,2,16,19,34–42,61–85 |

| Training, personnel and supervision in peer support | Despite the lack of information and ambiguity of the peer supporter's role and procedures underlying his integration in organisations (selection, training and supervision), there is a consensus in the literature on his characteristics. Therefore, a peer supporter should: -have the same pathology as the target population, but be further along in recovery; -undergo a selection process; -receive effective training; -receive regular supervision; -undergo selection, training and supervision by peers or mental health professionals. | 1,2,13,15,18,26,36,43–52,61–64,71–73,75,76,86,87 |

| Peer support models and the delivery of peer support | Peer support models are mentioned in only a few studies. In the case of the majority of peer support programmes their function is not well defined and varies according to the institution. We concluded that peer support programmes can: -be implemented in various settings; -be of variable duration. Most of the studies suggest that peer support should take the form of peers working part-time in shifts. | 15,37,39,41–44,47–49,51,53–59,61,62,64–68,75,76,78,83,86,88 |

| Evaluation and effectiveness of peer support | Evaluation procedures for peer support programmes are a gap in information on this practice. We can conclude only that they should include: -specific methods; -feedback from internal and external evaluators. Several authors suggest that, despite the lack of evidence on efficacy peer support has benefits including: -reducing the costs of mental health services; -improving the efficacy of the mental health services; -Increasing services user satisfaction with mental health services. | 1,2,15,16,19,37,43,44,49,53,58,59–63,65,69,70,76,80–84,86,87,89 |

The survey included 77 statements based on a systematic review and on an Australian study survey.10,32 Fifty-two of the 77 statements (67.5%) achieved consensus in Round 1. In the Round 2 raters were asked to evaluate the remaining 25 statements and of these, thirteen statements (52%) achieved consensus. Altogether, 65 of 77 statements (84.4%) achieved a consensus. The areas of consensus are listed and summarised at Appendix 1.

Based on these results, key recommendations were developed in the following eight areas: (a) goals and principles of peer support; (b) selection of peer supporters; (c) training and accreditation of peer supporters; (d) role of mental health professionals; (e) role of peer supporters; (f) access to peer supporters; (g) looking after peer supporters and (h) programme evaluation. These recommendations should be implemented according to the specific context of the programme.

On the basis of the consensus results from the online survey, eight guiding principles of peer support can be proposed. According to the expert panel, the goals of peer support (a) are: to provide an empathetic listening ear; to provide low level psychological intervention; to advocate for peers in disputes with management and colleagues; to identify peers who may be at risk to themselves or others; to facilitate access to professional help; to encourage compliance with treatment; to improve the functioning of individuals in the contexts in which they choose to live, learn, work and socialise; to reduce the likelihood of relapse and hospitalisation and to promote physical and mental health and well-being in the broader sense. Peer support does not pretend to be a treatment for psychiatric disorders. In addition to these goals, the importance of spontaneous or informal peer support during a day's work and the availability of peer support programmes for people with a long history of mental health problems were recognised.

With respect to the selection of peer supporters (b), it was unanimously recommended that the peer supporters should undergo an application and selection process before being appointed. The experts suggested that the selection process should include approval of a potential peer supporter by members of the target user group as well as a panel of experts, including mental health professionals and people with mental health problems. The consensus was that a peer supporter must be a member of the target population, someone with considerable experience of mental health problems who is respected by his or her peers.

The panel agreed that training (c) based on simple psychological techniques and information about other support services and psychological treatment should be provided to the peer supporters. This is consistent with the consensus disagreement with the statement that ‘peer supporters do not require training to fulfil their role’. It was also agreed that peer supporters should meet specific standards before they took up the role and that performance might be assessed through role plays, interviews or written tests. Participation in regular supervisions, updating of their training and the maintenance of accreditation was recommended, more specifically it was recommended that peer supporters should undergo a regular evaluation with either a senior peer supporter or a mental health professional.

In terms of the role of mental health professionals (d), the panel was of the opinion that they should participate in training and supervision of peer supporters and that an appropriately qualified mental health professional should be responsible for all peer support programmes.

There was agreement that the role of peer supporters (e) should be to provide continuing support to users for as long as it is beneficial. Every case should be discussed with a mental health professional and confidentiality should be maintained throughout the peer support process, with the exception of clinical supervision within the peer support programme or when the peer support user poses a risk to him- or herself or others.

In terms of access to peer supporters (f) the consensus was that peer supporters working with mental health professionals should act as the initial point of contact with the service user. There was also a consensus that users should be able to select a peer supporter from a pool. The panel also agreed that peer supporters should be available on-call in a defined schedule i.e. a roster system should be used so that peer supporters are not on duty all the time and there is some flexibility to deal with specific situations and emergencies.

In view of the requirements and responsibilities associated with the role of peer supporter participants suggested that peer supporters should be able to obtain guidance and advice easily from an appropriately trained mental health professional when necessary (g); this could implemented through the organisation of both regular peer supervision and regular supervision by either a senior peer supporter or a mental health professional. It was also recommended that peer supporters be offered support.

The panel agreed that the peer support programmes should be integrated with other rehabilitation programmes and should: have the capability to make a direct referral to a mental health professional; be tailored to the needs of the target group; have full organisational support and acceptance; establish the duration and frequency of the programme before implementation; establish clear goals linked to specific outcomes before implementation; (h) be evaluated by an external, independent evaluator in consultation with the peer support team. Participants also agreed that an evaluation must include qualitative and quantitative feedback from users and objective indicators such as absenteeism, sick leave, staff turnover. It was recommended that measures such as simple checklists to monitor progress be administered regularly where possible. Success indicators for peer support programmes might include: an increase in appropriate referrals for professional assistance; increased work performance; an improvement in overall staff satisfaction within the organisation; a reduction in the stigma associated with mental health problems; reduced sick leave and staff turnover (see Appendix 1).

DiscussionDespite the increasing rate of publication on the subject (Fig. 1), there is a lack of information about the use of peer support for mental health problems, particularly in terms of the evaluation and efficacy of peer support programmes, and the role of the peer supporter in mental health services. Lack of information and evidence about peer support means that the practice attracts controversy and guidelines for implantation are ambiguous; this has a negative impact on the implementation of peer support services as part of mental health services.

This is the first study in Portugal which has attempted to generate a consensus among a group of mental health service users and professionals, in order to create guidelines that will help mental health service providers implement peer support. To date there has been no consensus on best practice and peer-support models vary widely across organisations.10

The Delphi process is a valuable way of achieving consensus10 before a body of rigorous research on which to base guidelines is available. To improve acceptance of the consensus by the wider community, we used a group of independent individuals that was heterogeneous in terms of gender, age, connection to mental health services (clinical and mental health professionals, people with mental health problems, academics and researchers and service managers and directors) and length of involvement with mental health services. The fact that 12 statements did not achieve consensus indicates that the panel did not simply agree with preconceived ideas. The high retention of raters across the two rounds was a major positive feature of this study.

This study has some limitations. First of all, in Portugal information about peer support programmes targeted at rehabilitation of mental health problems is very limited. In addition although many statements achieved a consensus higher than 90% of raters, for some statements the consensus was only slightly above the required 70%, suggesting significant differences of opinion. In-depth analysis of those items and the statements that did not achieve consensus, generally reflected differences in connections with mental health services i.e. differences of opinion between mental health service users and professionals. It is therefore important to view these recommendations as guidelines rather than rigid rules; programmes should make exceptions wherever an alternative approach would meet the needs of the target population better.15 Despite these limitations, this study has the advantage of using an easily reproducible method, and contributes to the growing body of studies of peer support in Portugal and other countries.

The guidelines presented in this study are the result of a literature review and a survey carried out among mental health professionals and service users. Additional research on the role of peer support in the treatment of mental health problems is required to demonstrate the effectiveness of this practice and provide additional evidence on which to base guidelines for practice. This national consensus may be used as a starting point for the design and implementation of future peer support programmes in mental health organisations, and for future research. However, it is important that future research in this field concentrates on establishing robust, strong evidence on the effectiveness of peer support in mental health services in Portugal, with an emphasis on use of randomised, controlled trials. Peer support is increasingly important in the field of psychosocial rehabilitation of people with mental health problems, and this study provided valuable evidence on which to base the dissemination of this intervention in Portuguese mental health institutions. This study reflects the limited development of peer support in Portugal; according to the scientific databases research into peer support in Portugal is almost non-existent, suggesting that further studies are required.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

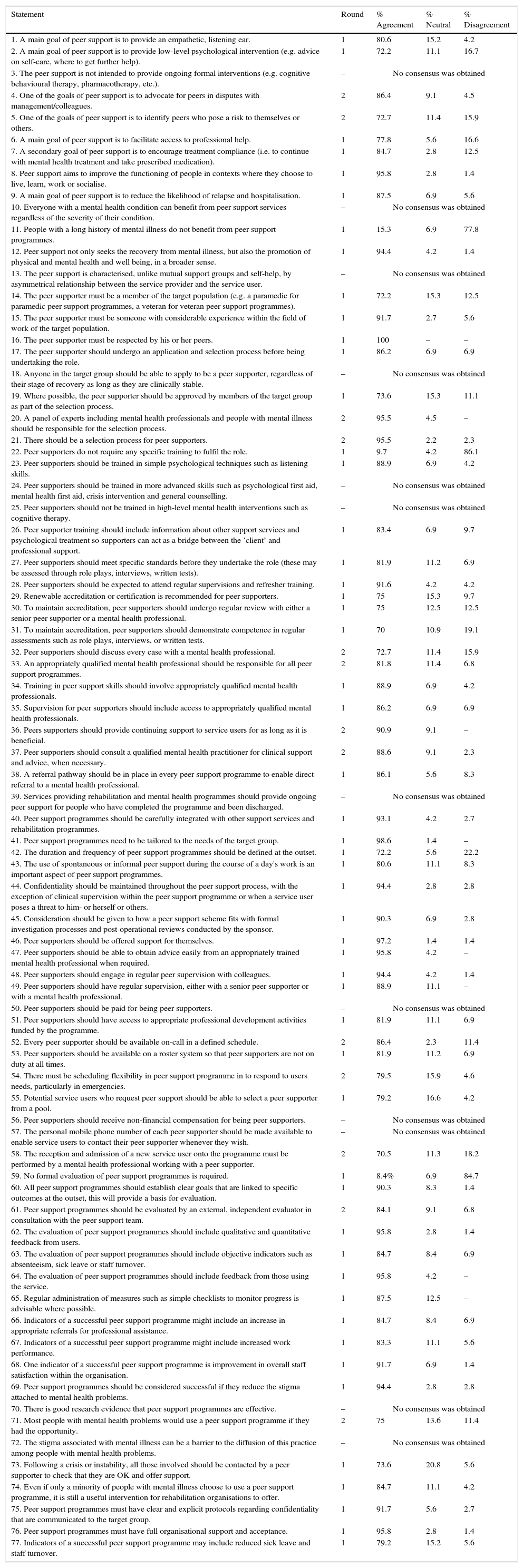

| Statement | Round | % Agreement | % Neutral | % Disagreement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. A main goal of peer support is to provide an empathetic, listening ear. | 1 | 80.6 | 15.2 | 4.2 |

| 2. A main goal of peer support is to provide low-level psychological intervention (e.g. advice on self-care, where to get further help). | 1 | 72.2 | 11.1 | 16.7 |

| 3. The peer support is not intended to provide ongoing formal interventions (e.g. cognitive behavioural therapy, pharmacotherapy, etc.). | – | No consensus was obtained | ||

| 4. One of the goals of peer support is to advocate for peers in disputes with management/colleagues. | 2 | 86.4 | 9.1 | 4.5 |

| 5. One of the goals of peer support is to identify peers who pose a risk to themselves or others. | 2 | 72.7 | 11.4 | 15.9 |

| 6. A main goal of peer support is to facilitate access to professional help. | 1 | 77.8 | 5.6 | 16.6 |

| 7. A secondary goal of peer support is to encourage treatment compliance (i.e. to continue with mental health treatment and take prescribed medication). | 1 | 84.7 | 2.8 | 12.5 |

| 8. Peer support aims to improve the functioning of people in contexts where they choose to live, learn, work or socialise. | 1 | 95.8 | 2.8 | 1.4 |

| 9. A main goal of peer support is to reduce the likelihood of relapse and hospitalisation. | 1 | 87.5 | 6.9 | 5.6 |

| 10. Everyone with a mental health condition can benefit from peer support services regardless of the severity of their condition. | – | No consensus was obtained | ||

| 11. People with a long history of mental illness do not benefit from peer support programmes. | 1 | 15.3 | 6.9 | 77.8 |

| 12. Peer support not only seeks the recovery from mental illness, but also the promotion of physical and mental health and well being, in a broader sense. | 1 | 94.4 | 4.2 | 1.4 |

| 13. The peer support is characterised, unlike mutual support groups and self-help, by asymmetrical relationship between the service provider and the service user. | – | No consensus was obtained | ||

| 14. The peer supporter must be a member of the target population (e.g. a paramedic for paramedic peer support programmes, a veteran for veteran peer support programmes). | 1 | 72.2 | 15.3 | 12.5 |

| 15. The peer supporter must be someone with considerable experience within the field of work of the target population. | 1 | 91.7 | 2.7 | 5.6 |

| 16. The peer supporter must be respected by his or her peers. | 1 | 100 | – | – |

| 17. The peer supporter should undergo an application and selection process before being undertaking the role. | 1 | 86.2 | 6.9 | 6.9 |

| 18. Anyone in the target group should be able to apply to be a peer supporter, regardless of their stage of recovery as long as they are clinically stable. | – | No consensus was obtained | ||

| 19. Where possible, the peer supporter should be approved by members of the target group as part of the selection process. | 1 | 73.6 | 15.3 | 11.1 |

| 20. A panel of experts including mental health professionals and people with mental illness should be responsible for the selection process. | 2 | 95.5 | 4.5 | – |

| 21. There should be a selection process for peer supporters. | 2 | 95.5 | 2.2 | 2.3 |

| 22. Peer supporters do not require any specific training to fulfil the role. | 1 | 9.7 | 4.2 | 86.1 |

| 23. Peer supporters should be trained in simple psychological techniques such as listening skills. | 1 | 88.9 | 6.9 | 4.2 |

| 24. Peer supporters should be trained in more advanced skills such as psychological first aid, mental health first aid, crisis intervention and general counselling. | – | No consensus was obtained | ||

| 25. Peer supporters should not be trained in high-level mental health interventions such as cognitive therapy. | – | No consensus was obtained | ||

| 26. Peer supporter training should include information about other support services and psychological treatment so supporters can act as a bridge between the ‘client’ and professional support. | 1 | 83.4 | 6.9 | 9.7 |

| 27. Peer supporters should meet specific standards before they undertake the role (these may be assessed through role plays, interviews, written tests). | 1 | 81.9 | 11.2 | 6.9 |

| 28. Peer supporters should be expected to attend regular supervisions and refresher training. | 1 | 91.6 | 4.2 | 4.2 |

| 29. Renewable accreditation or certification is recommended for peer supporters. | 1 | 75 | 15.3 | 9.7 |

| 30. To maintain accreditation, peer supporters should undergo regular review with either a senior peer supporter or a mental health professional. | 1 | 75 | 12.5 | 12.5 |

| 31. To maintain accreditation, peer supporters should demonstrate competence in regular assessments such as role plays, interviews, or written tests. | 1 | 70 | 10.9 | 19.1 |

| 32. Peer supporters should discuss every case with a mental health professional. | 2 | 72.7 | 11.4 | 15.9 |

| 33. An appropriately qualified mental health professional should be responsible for all peer support programmes. | 2 | 81.8 | 11.4 | 6.8 |

| 34. Training in peer support skills should involve appropriately qualified mental health professionals. | 1 | 88.9 | 6.9 | 4.2 |

| 35. Supervision for peer supporters should include access to appropriately qualified mental health professionals. | 1 | 86.2 | 6.9 | 6.9 |

| 36. Peers supporters should provide continuing support to service users for as long as it is beneficial. | 2 | 90.9 | 9.1 | – |

| 37. Peer supporters should consult a qualified mental health practitioner for clinical support and advice, when necessary. | 2 | 88.6 | 9.1 | 2.3 |

| 38. A referral pathway should be in place in every peer support programme to enable direct referral to a mental health professional. | 1 | 86.1 | 5.6 | 8.3 |

| 39. Services providing rehabilitation and mental health programmes should provide ongoing peer support for people who have completed the programme and been discharged. | – | No consensus was obtained | ||

| 40. Peer support programmes should be carefully integrated with other support services and rehabilitation programmes. | 1 | 93.1 | 4.2 | 2.7 |

| 41. Peer support programmes need to be tailored to the needs of the target group. | 1 | 98.6 | 1.4 | – |

| 42. The duration and frequency of peer support programmes should be defined at the outset. | 1 | 72.2 | 5.6 | 22.2 |

| 43. The use of spontaneous or informal peer support during the course of a day's work is an important aspect of peer support programmes. | 1 | 80.6 | 11.1 | 8.3 |

| 44. Confidentiality should be maintained throughout the peer support process, with the exception of clinical supervision within the peer support programme or when a service user poses a threat to him- or herself or others. | 1 | 94.4 | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| 45. Consideration should be given to how a peer support scheme fits with formal investigation processes and post-operational reviews conducted by the sponsor. | 1 | 90.3 | 6.9 | 2.8 |

| 46. Peer supporters should be offered support for themselves. | 1 | 97.2 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| 47. Peer supporters should be able to obtain advice easily from an appropriately trained mental health professional when required. | 1 | 95.8 | 4.2 | – |

| 48. Peer supporters should engage in regular peer supervision with colleagues. | 1 | 94.4 | 4.2 | 1.4 |

| 49. Peer supporters should have regular supervision, either with a senior peer supporter or with a mental health professional. | 1 | 88.9 | 11.1 | – |

| 50. Peer supporters should be paid for being peer supporters. | – | No consensus was obtained | ||

| 51. Peer supporters should have access to appropriate professional development activities funded by the programme. | 1 | 81.9 | 11.1 | 6.9 |

| 52. Every peer supporter should be available on-call in a defined schedule. | 2 | 86.4 | 2.3 | 11.4 |

| 53. Peer supporters should be available on a roster system so that peer supporters are not on duty at all times. | 1 | 81.9 | 11.2 | 6.9 |

| 54. There must be scheduling flexibility in peer support programme in to respond to users needs, particularly in emergencies. | 2 | 79.5 | 15.9 | 4.6 |

| 55. Potential service users who request peer support should be able to select a peer supporter from a pool. | 1 | 79.2 | 16.6 | 4.2 |

| 56. Peer supporters should receive non-financial compensation for being peer supporters. | – | No consensus was obtained | ||

| 57. The personal mobile phone number of each peer supporter should be made available to enable service users to contact their peer supporter whenever they wish. | – | No consensus was obtained | ||

| 58. The reception and admission of a new service user onto the programme must be performed by a mental health professional working with a peer supporter. | 2 | 70.5 | 11.3 | 18.2 |

| 59. No formal evaluation of peer support programmes is required. | 1 | 8.4% | 6.9 | 84.7 |

| 60. All peer support programmes should establish clear goals that are linked to specific outcomes at the outset, this will provide a basis for evaluation. | 1 | 90.3 | 8.3 | 1.4 |

| 61. Peer support programmes should be evaluated by an external, independent evaluator in consultation with the peer support team. | 2 | 84.1 | 9.1 | 6.8 |

| 62. The evaluation of peer support programmes should include qualitative and quantitative feedback from users. | 1 | 95.8 | 2.8 | 1.4 |

| 63. The evaluation of peer support programmes should include objective indicators such as absenteeism, sick leave or staff turnover. | 1 | 84.7 | 8.4 | 6.9 |

| 64. The evaluation of peer support programmes should include feedback from those using the service. | 1 | 95.8 | 4.2 | – |

| 65. Regular administration of measures such as simple checklists to monitor progress is advisable where possible. | 1 | 87.5 | 12.5 | – |

| 66. Indicators of a successful peer support programme might include an increase in appropriate referrals for professional assistance. | 1 | 84.7 | 8.4 | 6.9 |

| 67. Indicators of a successful peer support programme might include increased work performance. | 1 | 83.3 | 11.1 | 5.6 |

| 68. One indicator of a successful peer support programme is improvement in overall staff satisfaction within the organisation. | 1 | 91.7 | 6.9 | 1.4 |

| 69. Peer support programmes should be considered successful if they reduce the stigma attached to mental health problems. | 1 | 94.4 | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| 70. There is good research evidence that peer support programmes are effective. | – | No consensus was obtained | ||

| 71. Most people with mental health problems would use a peer support programme if they had the opportunity. | 2 | 75 | 13.6 | 11.4 |

| 72. The stigma associated with mental illness can be a barrier to the diffusion of this practice among people with mental health problems. | – | No consensus was obtained | ||

| 73. Following a crisis or instability, all those involved should be contacted by a peer supporter to check that they are OK and offer support. | 1 | 73.6 | 20.8 | 5.6 |

| 74. Even if only a minority of people with mental illness choose to use a peer support programme, it is still a useful intervention for rehabilitation organisations to offer. | 1 | 84.7 | 11.1 | 4.2 |

| 75. Peer support programmes must have clear and explicit protocols regarding confidentiality that are communicated to the target group. | 1 | 91.7 | 5.6 | 2.7 |

| 76. Peer support programmes must have full organisational support and acceptance. | 1 | 95.8 | 2.8 | 1.4 |

| 77. Indicators of a successful peer support programme may include reduced sick leave and staff turnover. | 1 | 79.2 | 15.2 | 5.6 |

Please cite this article as: Campos F, Sousa A, Rodrigues V, Marques A, Queirós C, Dores A. Directrices prácticas para programas de apoyo entre personas con enfermedad mental. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2016;9:97–110.