Lithium is one of the first therapeutic options for bipolar disorder, which is characterised by recurrent mood swings that strongly reduce quality of life. Our purpose was to achieve professional consensus criteria to define the contents of an information sheet for patients with bipolar disorder that are starting treatment with lithium.

Materials and methodsA modified Delphi method in two rounds was used. The Scientific Committee—made up by nine psychiatrists—created a 20-item questionnaire about the information that must be given to the patient treated with lithium and selected a panel of ambulatory and hospital psychiatric experts to agree on this information. Panelists scored each item based on a Likert scale of 9 points and could add comments in a confidential manner. It was considered consensus in agreement when median scores were within the range of [7–9] and in disagreement within the range of [1–3].

ResultsA high level of consensus was reached. In the first round, there was agreement on 17 out of 20 items and, after the second round, there was disagreement on just one item containing information about the discovery of lithium. Finally, said item was modified in the Patient's Information Sheet based on the comments suggested by the panelists.

ConclusionsThis study allowed to create an information sheet for patients with bipolar disorder under treatment with lithium, with information agreed upon by a group of experts from different health care settings.

El litio constituye una de las primeras opciones terapéuticas del trastorno bipolar, el cual se caracteriza por cambios recurrentes en el estado de ánimo que reducen fuertemente la calidad de vida. Nuestro objetivo fue alcanzar un consenso de criterio profesional para definir los contenidos de una hoja de información al paciente con trastorno bipolar que inicia tratamiento con litio.

Material y MétodosSe empleó el método Delphi modificado en dos rondas. El Comité Científico —constituido por nueve psiquiatras— elaboró un cuestionario con 20 ítems sobre la información que debe comunicarse al paciente tratado con litio y seleccionó un panel de expertos psiquiatras del ámbito ambulatorio y hospitalario para consensuar esta información. Los panelistas puntuaron cada ítem según una escala Likert de 9 puntos y podían añadir comentarios de manera confidencial. Se consideró consenso en el acuerdo cuando la mediana de las puntuaciones se encontró en el rango [7–9], y en desacuerdo en el rango [1–3].

ResultadosSe alcanzó un alto nivel de consenso. En la primera ronda, se alcanzó acuerdo en 17 de los 20 ítems, y tras la segunda ronda, solo quedó un ítem en desacuerdo, el cual contenía información sobre el descubrimiento del litio. Finalmente, dicho ítem fue modificado en la hoja de información del paciente siguiendo los comentarios sugeridos por los panelistas.

ConclusionesEste trabajo permitió elaborar una hoja de información para el paciente con trastorno bipolar en tratamiento con litio, con información consensuada por un grupo de expertos de distintos ámbitos de la asistencia sanitaria.

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a chronic recurrent disorder characterised by changes in mood and energy, often resulting in functional and cognitive impairment that severely reduces quality of life.1,2 It also affects the general health of the subject, presenting other associated comorbidities such as diabetes, obesity or cardiovascular problems.1 It is a common disorder in the population and one of the main causes of disability among young people.1,3 According to a large cross-sectional survey with more than 60,000 participants conducted in 11 countries, the prevalence of bipolar disorder is 2.4% — including BD type I, type II, and disorders with subthreshold symptoms or with bipolar features that do not meet the criteria for any specific type of BD.4 However, there is great variability between countries,4,5 ranging from .1% in India to 4.4% in the United States.4 The exact reason for this variability is not known, although it has been suggested that factors such as ethnicity, cultural factors and variations in diagnostic criteria and study methodology may play a role.5 According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), BD generates the second most days out of role, since it mainly affects the working population, at great cost to society.3,6,7 BD has a high mortality rate, with suicide being one of the main causes. In fact, the incidence of suicide in the BD population is 20 times higher than in the rest of the population, especially if untreated.8,9

For more than 40 years, lithium has been the treatment of choice as a mood stabiliser in BD and to prevent the risk of relapse or recurrence.1,10–13 Other drugs such as antiepileptics and antipsychotics are now also recommended and used in clinical practice. However, lithium, both in monotherapy and in combination, is one of the first therapeutic options in BD due to its high effectiveness in the prevention of manic and depressive episodes, and its good results in the prevention of suicide.10,11,13–18 However, lithium may also be associated with some adverse events mainly related to the endocrine system (thyroid function),19 especially in women under 60 years of age, who are at the highest risk of developing these thyroid disorders.19 In the very long term, and after prolonged periods of treatment (more than 20 years), renal problems may occur in a subgroup of patients.20 In addition, lithium has a narrow therapeutic range and patients need to be closely monitored to avoid sub- or supratherapeutic doses, and monitor health status and onset of side effects.12,19

Fear of adverse effects is one of the main reasons that patients abandon treatment, which has direct consequences on the control of their disease.21,22 Although it may seem obvious, a treatment cannot be effective if the patient does not take the medication or takes it at a sub-therapeutic dose.21 Non-adherence to treatment is one of the main challenges in the management of mental illness.21,22 According to several studies, the adherence rate in BD is no more than 35%.21,23 Some authors have suggested gradual dose titration at the start of treatment, because if a patient’s experience is poor after first exposure to the drug it may make them believe that they do not tolerate it well, which could have implications for long-term adherence. There is even the risk of developing nocebo phenomena in sensitised individuals.17 In addition to adverse events, other common reasons given by patients for discontinuing treatment include denial of the disease and not considering medication necessary.22 To address these issues, patient education and improved patient-physician communication have been shown to help improve adherence.21,24 Therefore, it is important to provide the patient – or legal guardian – with rigorous and accessible information about the treatment they are about to start. However, clinicians often find it difficult to select the main messages to communicate.

The primary aim of this paper was to reach a consensus of professional judgement using Delphi methodology to define the contents of a patient information sheet on the treatment of BD with lithium salts.

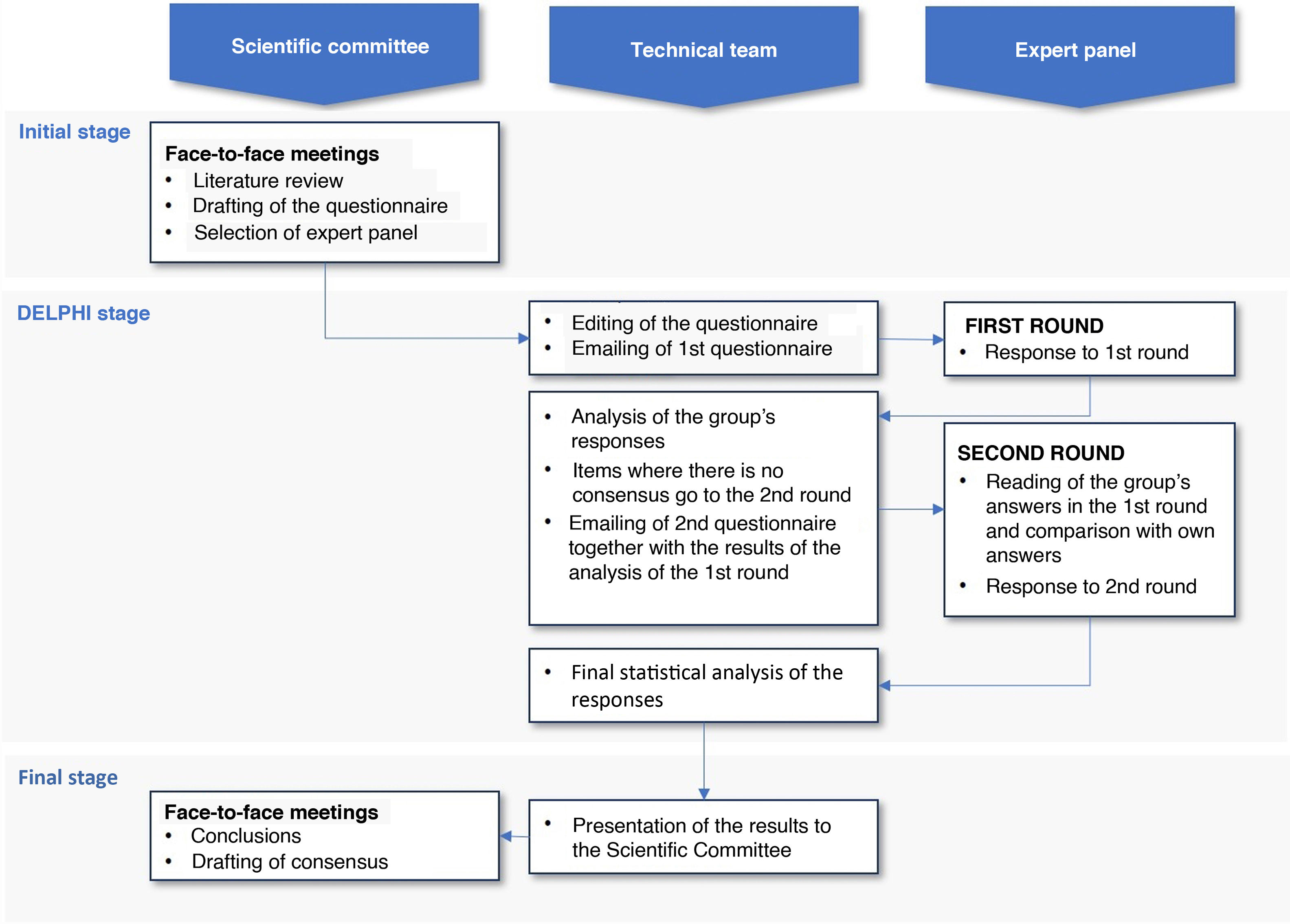

Material and methodsStudy designThe modified Delphi method25 was used to define the contents of the patient information sheet for BD patients treated with lithium salts, a structured, reliable, and remote professional consensus technique widely used in the healthcare field. This technique makes it possible to explore and pool the opinions of a professional group on the subject of interest without the difficulties and disadvantages inherent to consensus methods with face-to-face discussion (having to travel, influence bias, non-confidential interaction, etc.). Its main advantages are: (a) anonymity in defending individual opinions; (b) controlled interaction between the members of the expert panel; (c) the opportunity to reflect and reconsider an opinion between the first and second round without losing anonymity; and (d) statistical validation of the consensus achieved.

Two successive rounds were conducted in which the individual and anonymous opinion of each panellist was solicited by means of an email survey. Between the two rounds, the panellists received the group results of the first questionnaire so that they could confidentially contrast their opinions with those of the other participants and take the opportunity to reconsider their opinion.

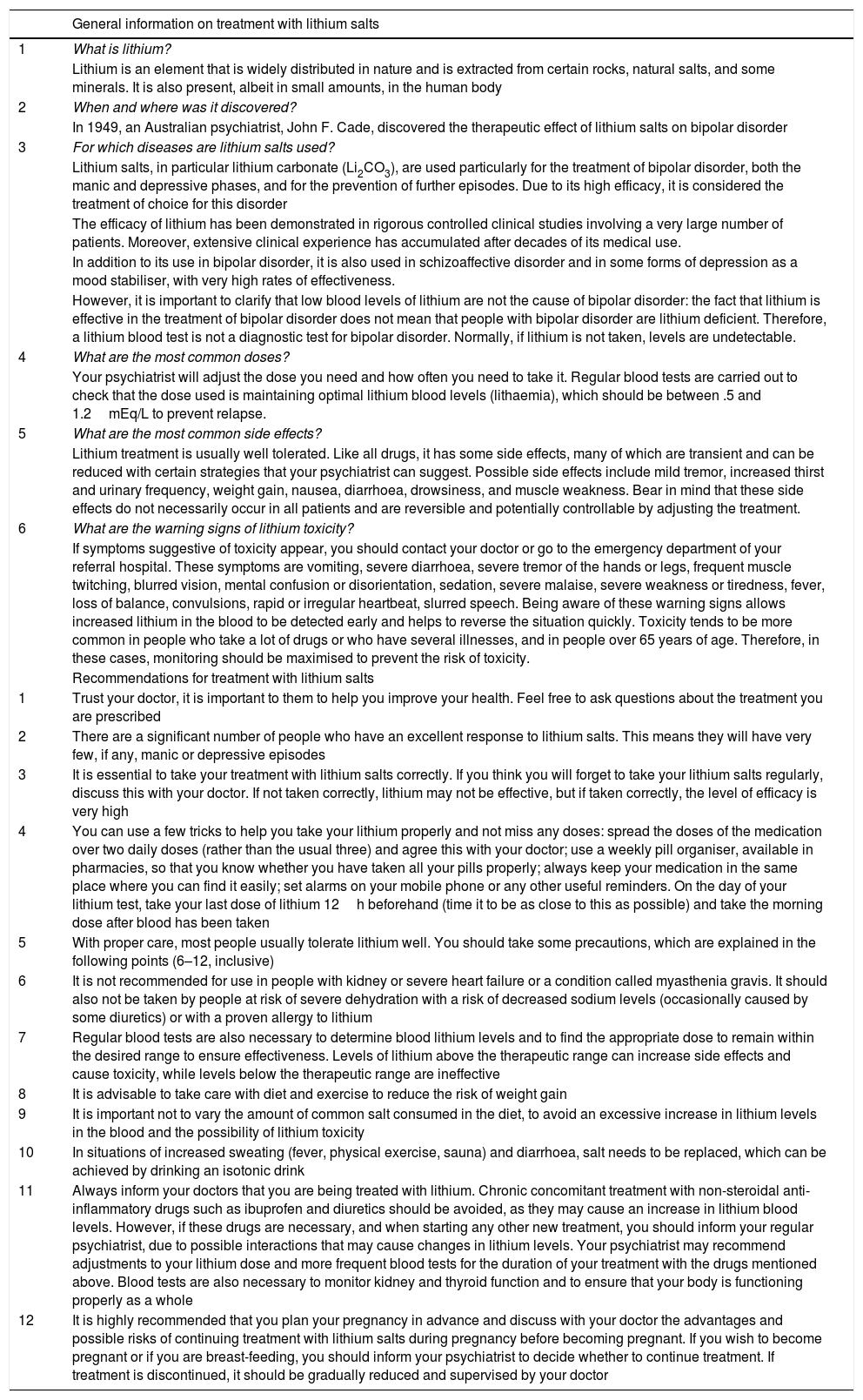

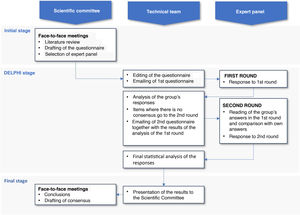

This study was conducted in 3 phases (Fig. 1): (a) initial phase, in which the scientific committee met to select the panel and develop the questionnaire; (b) Delphi phase, in which 2 successive rounds – separated by intermediate processing – were applied to expert panellists; (c) final phase, in which after the compilation and analysis of the results by the technical team, the results were presented to the scientific committee in a face-to-face session and the conclusions were discussed for the final draft of the patient information sheet.

ParticipantsThe scientific committee, comprising 9 psychiatrists from different Spanish hospitals and research centres, oversaw drafting the questionnaire and selecting the panel of experts. All members of the scientific committee had extensive clinical experience in the treatment of BD and in the use of lithium salts and were endorsed as reference researchers by the Spanish Society of Biological Psychiatry (SEPB) (www.sepb.es). A snowballing strategy was used to recruit the panellists, based on the professional contacts of the committee members, who in turn proposed new candidates from their professional backgrounds who were experts in the field. The panellists were psychiatrists from ambulatory and hospital settings, by necessity experienced in the use of lithium salts and with impactful publications on BD. Geographical distribution and distribution by type of care setting were considered in the selection of the panellists.

The technical team managed and supervised the process, overseeing implementation of the method, statistical analysis, and interpretation of results.

Drafting the questionnaireThe scientific committee defined the contents of the Delphi questionnaire after grouping and synthesising all the information obtained from the literature review and the committee's working meetings.

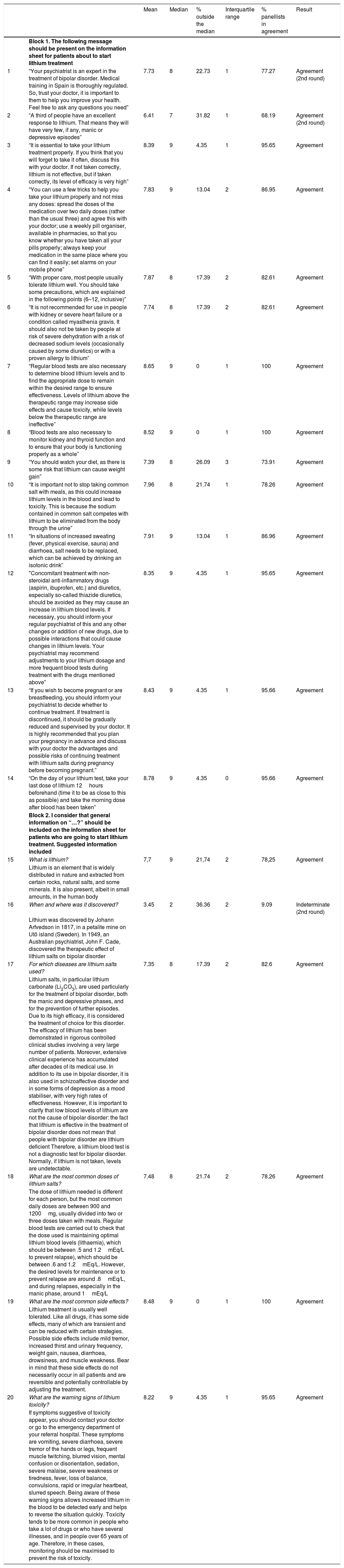

The final version of the questionnaire was divided into 2 blocks (Table 1). The first block included 14 items on aspects that should be made known to the person starting lithium treatment (items 1–14); and the second block included 6 items dealing with general information on lithium (items 15–20).

Results of the level of consensus reached by all the experts on each item after 2 rating rounds.

| Mean | Median | % outside the median | Interquartile range | % panellists in agreement | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1. The following message should be present on the information sheet for patients about to start lithium treatment | |||||||

| 1 | “Your psychiatrist is an expert in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Medical training in Spain is thoroughly regulated. So, trust your doctor, it is important to them to help you improve your health. Feel free to ask any questions you need” | 7.73 | 8 | 22.73 | 1 | 77.27 | Agreement (2nd round) |

| 2 | “A third of people have an excellent response to lithium. That means they will have very few, if any, manic or depressive episodes” | 6.41 | 7 | 31.82 | 1 | 68.19 | Agreement (2nd round) |

| 3 | “It is essential to take your lithium treatment properly. If you think that you will forget to take it often, discuss this with your doctor. If not taken correctly, lithium is not effective, but if taken correctly, its level of efficacy is very high” | 8.39 | 9 | 4.35 | 1 | 95.65 | Agreement |

| 4 | “You can use a few tricks to help you take your lithium properly and not miss any doses: spread the doses of the medication over two daily doses (rather than the usual three) and agree this with your doctor; use a weekly pill organiser, available in pharmacies, so that you know whether you have taken all your pills properly; always keep your medication in the same place where you can find it easily; set alarms on your mobile phone” | 7.83 | 9 | 13.04 | 2 | 86.95 | Agreement |

| 5 | “With proper care, most people usually tolerate lithium well. You should take some precautions, which are explained in the following points (6–12, inclusive)” | 7.87 | 8 | 17.39 | 2 | 82.61 | Agreement |

| 6 | “It is not recommended for use in people with kidney or severe heart failure or a condition called myasthenia gravis. It should also not be taken by people at risk of severe dehydration with a risk of decreased sodium levels (occasionally caused by some diuretics) or with a proven allergy to lithium” | 7.74 | 8 | 17.39 | 2 | 82.61 | Agreement |

| 7 | “Regular blood tests are also necessary to determine blood lithium levels and to find the appropriate dose to remain within the desired range to ensure effectiveness. Levels of lithium above the therapeutic range may increase side effects and cause toxicity, while levels below the therapeutic range are ineffective” | 8.65 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 100 | Agreement |

| 8 | “Blood tests are also necessary to monitor kidney and thyroid function and to ensure that your body is functioning properly as a whole” | 8.52 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 100 | Agreement |

| 9 | “You should watch your diet, as there is some risk that lithium can cause weight gain” | 7.39 | 8 | 26.09 | 3 | 73.91 | Agreement |

| 10 | “It is important not to stop taking common salt with meals, as this could increase lithium levels in the blood and lead to toxicity. This is because the sodium contained in common salt competes with lithium to be eliminated from the body through the urine” | 7.96 | 8 | 21.74 | 1 | 78.26 | Agreement |

| 11 | “In situations of increased sweating (fever, physical exercise, sauna) and diarrhoea, salt needs to be replaced, which can be achieved by drinking an isotonic drink” | 7.91 | 9 | 13.04 | 1 | 86.96 | Agreement |

| 12 | "Concomitant treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (aspirin, ibuprofen, etc.) and diuretics, especially so-called thiazide diuretics, should be avoided as they may cause an increase in lithium blood levels. If necessary, you should inform your regular psychiatrist of this and any other changes or addition of new drugs, due to possible interactions that could cause changes in lithium levels. Your psychiatrist may recommend adjustments to your lithium dosage and more frequent blood tests during treatment with the drugs mentioned above” | 8.35 | 9 | 4.35 | 1 | 95.65 | Agreement |

| 13 | “If you wish to become pregnant or are breastfeeding, you should inform your psychiatrist to decide whether to continue treatment. If treatment is discontinued, it should be gradually reduced and supervised by your doctor. It is highly recommended that you plan your pregnancy in advance and discuss with your doctor the advantages and possible risks of continuing treatment with lithium salts during pregnancy before becoming pregnant.” | 8.43 | 9 | 4.35 | 1 | 95.66 | Agreement |

| 14 | “On the day of your lithium test, take your last dose of lithium 12hours beforehand (time it to be as close to this as possible) and take the morning dose after blood has been taken” | 8.78 | 9 | 4.35 | 0 | 95.66 | Agreement |

| Block 2. I consider that general information on “…?” should be included on the information sheet for patients who are going to start lithium treatment. Suggested information included | |||||||

| 15 | What is lithium? | 7,7 | 9 | 21,74 | 2 | 78,25 | Agreement |

| Lithium is an element that is widely distributed in nature and extracted from certain rocks, natural salts, and some minerals. It is also present, albeit in small amounts, in the human body | |||||||

| 16 | When and where was it discovered? | 3.45 | 2 | 36.36 | 2 | 9.09 | Indeterminate (2nd round) |

| Lithium was discovered by Johann Arfvedson in 1817, in a petalite mine on Utö island (Sweden). In 1949, an Australian psychiatrist, John F. Cade, discovered the therapeutic effect of lithium salts on bipolar disorder | |||||||

| 17 | For which diseases are lithium salts used? | 7.35 | 8 | 17.39 | 2 | 82.6 | Agreement |

| Lithium salts, in particular lithium carbonate (Li2CO3), are used particularly for the treatment of bipolar disorder, both the manic and depressive phases, and for the prevention of further episodes. Due to its high efficacy, it is considered the treatment of choice for this disorder. The efficacy of lithium has been demonstrated in rigorous controlled clinical studies involving a very large number of patients. Moreover, extensive clinical experience has accumulated after decades of its medical use. In addition to its use in bipolar disorder, it is also used in schizoaffective disorder and in some forms of depression as a mood stabiliser, with very high rates of effectiveness. However, it is important to clarify that low blood levels of lithium are not the cause of bipolar disorder: the fact that lithium is effective in the treatment of bipolar disorder does not mean that people with bipolar disorder are lithium deficient Therefore, a lithium blood test is not a diagnostic test for bipolar disorder. Normally, if lithium is not taken, levels are undetectable. | |||||||

| 18 | What are the most common doses of lithium salts? | 7.48 | 8 | 21.74 | 2 | 78.26 | Agreement |

| The dose of lithium needed is different for each person, but the most common daily doses are between 900 and 1200mg, usually divided into two or three doses taken with meals. Regular blood tests are carried out to check that the dose used is maintaining optimal lithium blood levels (lithaemia), which should be between .5 and 1.2mEq/L to prevent relapse), which should be between .6 and 1.2mEq/L. However, the desired levels for maintenance or to prevent relapse are around .8mEq/L, and during relapses, especially in the manic phase, around 1mEq/L | |||||||

| 19 | What are the most common side effects? | 8.48 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 100 | Agreement |

| Lithium treatment is usually well tolerated. Like all drugs, it has some side effects, many of which are transient and can be reduced with certain strategies. Possible side effects include mild tremor, increased thirst and urinary frequency, weight gain, nausea, diarrhoea, drowsiness, and muscle weakness. Bear in mind that these side effects do not necessarily occur in all patients and are reversible and potentially controllable by adjusting the treatment. | |||||||

| 20 | What are the warning signs of lithium toxicity? | 8.22 | 9 | 4.35 | 1 | 95.65 | Agreement |

| If symptoms suggestive of toxicity appear, you should contact your doctor or go to the emergency department of your referral hospital. These symptoms are vomiting, severe diarrhoea, severe tremor of the hands or legs, frequent muscle twitching, blurred vision, mental confusion or disorientation, sedation, severe malaise, severe weakness or tiredness, fever, loss of balance, convulsions, rapid or irregular heartbeat, slurred speech. Being aware of these warning signs allows increased lithium in the blood to be detected early and helps to reverse the situation quickly. Toxicity tends to be more common in people who take a lot of drugs or who have several illnesses, and in people over 65 years of age. Therefore, in these cases, monitoring should be maximised to prevent the risk of toxicity. |

The rating scale used for all questions was a 9-point Likert-type ordinal scale (minimum 1, strongly disagree; maximum 9, strongly agree), like the conventional format developed at UCLA-Rand Corporation for the method of assessing appropriate use of health technology.26 The response categories were described by linguistic qualifiers in 3 regions ([1–3], disagree; [4–6], neither agree nor disagree; [7–9], agree). The survey also allowed the possibility of adding free comments to each item confidentially.

Statistical analysis and interpretation of resultsTo analyse group opinion and the type of consensus reached on each question, we used the median position of the group scores and the level of agreement reached by the respondents, according to the following criteria:27 (a) There was considered to be consensus on an item when there was "agreement" of opinion in the panel, i.e., when more than two-thirds of the panellists scored the item in the same 3-point region in which the median was located, either in the region of disagree [1–3], neither agree nor disagree [4–6], or in the region of agree [7–9]. In this case, the median value determined the group consensus reached: the majority "disagree" with the item if the median was ≤3, or the majority "agree" with the item if the median was ≥7. Cases where the median was in the region [4–6] were considered "borderline" items for a representative majority of the group. b) There was considered to be no consensus on an item when there was "discordance" in the panel’s judgement, i.e., when the scores of a third or more of the panellists were in the region [1–3] and another third or more were in the region [7–9]. Those remaining items where neither concordance nor discordance was observed were considered to have an “indeterminate” level of consensus.

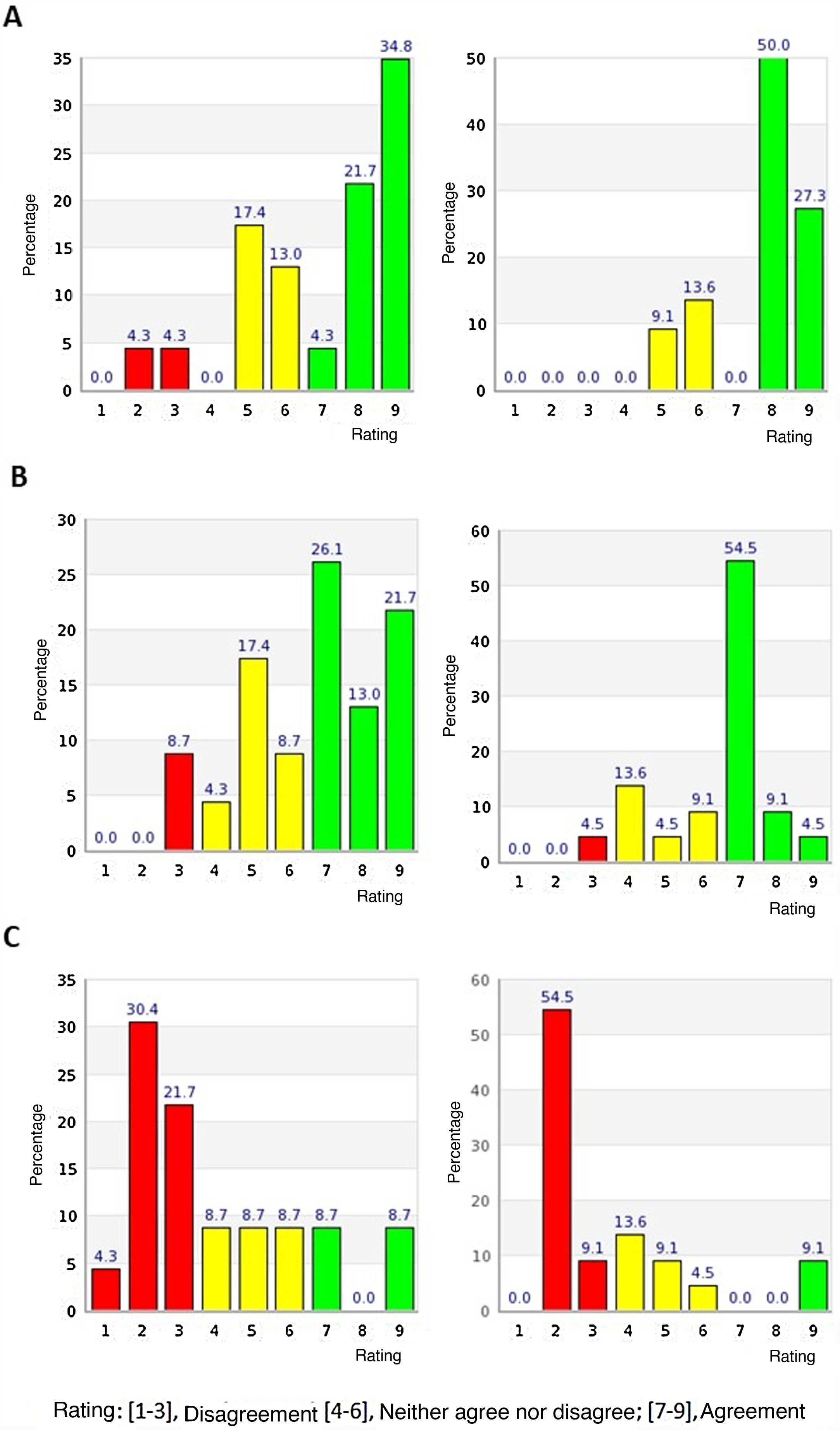

Items that were "borderline" or on which there was no consensus in the first round (including both items in “discordance” and items with an “indeterminate” level of consensus) were carried forward to the second Delphi round. Items with an interquartile range ≥4 points (range of scores contained between values p25 and p75 of the distribution) were also re-evaluated. Before moving on to the second round, the panellists were provided with the results of the first round in bar charts, together with comments and clarifications provided anonymously by each participant. They were then asked to make a second assessment of those items not agreed in the first round. In this second round, the items that were definitively agreed were identified following the same criteria as in the first round.

To compare between items, the mean score of the panellists on each question was calculated with its 95% confidence interval. The more extreme the mean score for an item, the clearer the consensus on the proposition expressed by each item was considered to be, either in agreement (mean closer to 9) or disagreement (mean closer to 1). The smaller width of the confidence interval was interpreted as an expression of greater unanimity of opinion in the group.

Items where consensus was not reached after completing the entire process were analysed descriptively to distinguish whether the lack of consensus was due to persistent disagreement of opinion among the panellists, or to the majority positioning of the panel in the borderline region regarding the item, i.e., the majority in the group said they neither agreed nor disagreed (score in the region [4–6]).

ResultsThe expert panel consisted of 22 psychiatrists (59% men and 41% women) from the Community of Madrid, Catalonia, Valencia, Andalusia, Castilla y León and the Basque Country.

All the panellists completed the 2 rounds of evaluation. In the first round, 12 of the 14 items in the first block and 5 of the 6 items in the second block were agreed according to the pre-established evaluation criteria; all of them in terms of agreement with the proposed statements on lithium treatment. The remaining items on which there was no consensus (items 1 and 2 of the first block and item 16 of the second block) were reconsidered in the second round. Table 1 shows the results obtained for each of the items in either the first or the second round, indicating the median, mean, interquartile range, percentage outside the median and percentage of panellists agreeing with each item. Fig. 2 shows the distribution of scores given by the panellists to the items on which no consensus was reached in the first round. The distribution of the experts' scores in the first round on all items is detailed in Appendix B Fig. S1 of the Supplementary material.

Distribution of the experts’ opinions on items where consensus was not reached in the first round (left panel) and distribution of opinions on the same items after the second round (right panel). Rating: [1–3], disagree; [4–6], neither agree nor disagree; [7–9], agree. (A) The message “Your psychiatrist is an expert in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Medical training in Spain is thoroughly regulated. Therefore trust your doctor, it is important to them to help you improve your health. Feel free to ask any questions you need” should be present on the information sheet for patients who are about to start treatment with lithium. (B) The message “A third of people have an excellent response to lithium. That means they will have very few, if any, manic or depressive episodes” should be present on the information sheet for the patient who is going to start lithium treatment. (C) I consider that general information regarding “When and where was it discovered?” should be present on the information sheet for the patient who is going to start treatment with lithium. Suggested information: “Lithium was discovered by Johann Arfvedson in 1817, in a petalite mine located on Utö Island (Sweden). In 1949, an Australian psychiatrist, John F. Cade, discovered the therapeutic effect of lithium salts in bipolar disorder”.

After the second round there was only one item, item 16, which remained indeterminate, neither agree nor disagree. This item, belonging to the second block, the panellists were asked whether they considered that general information regarding “When and where was lithium discovered?” should be present on the information sheet for patients starting lithium treatment. The information proposed in response to this question was: "Lithium was discovered by Johann Arfvedson in 1817, in a petalite mine located on Utö Island (Sweden). In 1949, an Australian psychiatrist, John F. Cade, discovered the therapeutic effect of lithium salts in bipolar disorder". In the second round, the median score for this item was 2 and the mean score 3.45, with the percentage of responses outside the 3-point region including the median being 36.36% and the interquartile range 2. Although in the majority the panellists disagreed with this item (63.6%), up to 27.2% of the experts considered this item borderline and only 9.1% agreed.

It is worth noting that in 8 of the 20 items there was consensus in the agreement of more than 95% of the panellists. Six in the first block (items 3, 7, 8, 12, 13 and 14) and the remaining two in the second block (items 19 and 20). The items in the first block addressed the importance of following lithium treatment correctly for it to be effective (item 3), the need for blood tests to measure lithaemia (items 7 and 8), guidelines on how to take lithium when bloods are taken (item 14), the need to consult a doctor, both in case of concomitant treatment with other drugs (item 12) and in case of pregnancy and breastfeeding (item 13). The 2 items in the second block contained information on the side effects of lithium (item 19), and warning signs of lithium toxicity (item 20) (Table 1).

The information sheet for BD patients starting treatment with lithium salts was drafted when the results were analysed, taking the comments of the panellists into account (Table 2). The scientific committee approved the inclusion in the patient information sheet of item 16, which had been left indeterminate, but amended it with the comments suggested by the panellists (Tables 1 and 2).

Patient information sheet for consent to treatment with lithium salts.

| General information on treatment with lithium salts | |

|---|---|

| 1 | What is lithium? |

| Lithium is an element that is widely distributed in nature and is extracted from certain rocks, natural salts, and some minerals. It is also present, albeit in small amounts, in the human body | |

| 2 | When and where was it discovered? |

| In 1949, an Australian psychiatrist, John F. Cade, discovered the therapeutic effect of lithium salts on bipolar disorder | |

| 3 | For which diseases are lithium salts used? |

| Lithium salts, in particular lithium carbonate (Li2CO3), are used particularly for the treatment of bipolar disorder, both the manic and depressive phases, and for the prevention of further episodes. Due to its high efficacy, it is considered the treatment of choice for this disorder | |

| The efficacy of lithium has been demonstrated in rigorous controlled clinical studies involving a very large number of patients. Moreover, extensive clinical experience has accumulated after decades of its medical use. | |

| In addition to its use in bipolar disorder, it is also used in schizoaffective disorder and in some forms of depression as a mood stabiliser, with very high rates of effectiveness. | |

| However, it is important to clarify that low blood levels of lithium are not the cause of bipolar disorder: the fact that lithium is effective in the treatment of bipolar disorder does not mean that people with bipolar disorder are lithium deficient. Therefore, a lithium blood test is not a diagnostic test for bipolar disorder. Normally, if lithium is not taken, levels are undetectable. | |

| 4 | What are the most common doses? |

| Your psychiatrist will adjust the dose you need and how often you need to take it. Regular blood tests are carried out to check that the dose used is maintaining optimal lithium blood levels (lithaemia), which should be between .5 and 1.2mEq/L to prevent relapse. | |

| 5 | What are the most common side effects? |

| Lithium treatment is usually well tolerated. Like all drugs, it has some side effects, many of which are transient and can be reduced with certain strategies that your psychiatrist can suggest. Possible side effects include mild tremor, increased thirst and urinary frequency, weight gain, nausea, diarrhoea, drowsiness, and muscle weakness. Bear in mind that these side effects do not necessarily occur in all patients and are reversible and potentially controllable by adjusting the treatment. | |

| 6 | What are the warning signs of lithium toxicity? |

| If symptoms suggestive of toxicity appear, you should contact your doctor or go to the emergency department of your referral hospital. These symptoms are vomiting, severe diarrhoea, severe tremor of the hands or legs, frequent muscle twitching, blurred vision, mental confusion or disorientation, sedation, severe malaise, severe weakness or tiredness, fever, loss of balance, convulsions, rapid or irregular heartbeat, slurred speech. Being aware of these warning signs allows increased lithium in the blood to be detected early and helps to reverse the situation quickly. Toxicity tends to be more common in people who take a lot of drugs or who have several illnesses, and in people over 65 years of age. Therefore, in these cases, monitoring should be maximised to prevent the risk of toxicity. | |

| Recommendations for treatment with lithium salts | |

| 1 | Trust your doctor, it is important to them to help you improve your health. Feel free to ask questions about the treatment you are prescribed |

| 2 | There are a significant number of people who have an excellent response to lithium salts. This means they will have very few, if any, manic or depressive episodes |

| 3 | It is essential to take your treatment with lithium salts correctly. If you think you will forget to take your lithium salts regularly, discuss this with your doctor. If not taken correctly, lithium may not be effective, but if taken correctly, the level of efficacy is very high |

| 4 | You can use a few tricks to help you take your lithium properly and not miss any doses: spread the doses of the medication over two daily doses (rather than the usual three) and agree this with your doctor; use a weekly pill organiser, available in pharmacies, so that you know whether you have taken all your pills properly; always keep your medication in the same place where you can find it easily; set alarms on your mobile phone or any other useful reminders. On the day of your lithium test, take your last dose of lithium 12h beforehand (time it to be as close to this as possible) and take the morning dose after blood has been taken |

| 5 | With proper care, most people usually tolerate lithium well. You should take some precautions, which are explained in the following points (6–12, inclusive) |

| 6 | It is not recommended for use in people with kidney or severe heart failure or a condition called myasthenia gravis. It should also not be taken by people at risk of severe dehydration with a risk of decreased sodium levels (occasionally caused by some diuretics) or with a proven allergy to lithium |

| 7 | Regular blood tests are also necessary to determine blood lithium levels and to find the appropriate dose to remain within the desired range to ensure effectiveness. Levels of lithium above the therapeutic range can increase side effects and cause toxicity, while levels below the therapeutic range are ineffective |

| 8 | It is advisable to take care with diet and exercise to reduce the risk of weight gain |

| 9 | It is important not to vary the amount of common salt consumed in the diet, to avoid an excessive increase in lithium levels in the blood and the possibility of lithium toxicity |

| 10 | In situations of increased sweating (fever, physical exercise, sauna) and diarrhoea, salt needs to be replaced, which can be achieved by drinking an isotonic drink |

| 11 | Always inform your doctors that you are being treated with lithium. Chronic concomitant treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen and diuretics should be avoided, as they may cause an increase in lithium blood levels. However, if these drugs are necessary, and when starting any other new treatment, you should inform your regular psychiatrist, due to possible interactions that may cause changes in lithium levels. Your psychiatrist may recommend adjustments to your lithium dose and more frequent blood tests for the duration of your treatment with the drugs mentioned above. Blood tests are also necessary to monitor kidney and thyroid function and to ensure that your body is functioning properly as a whole |

| 12 | It is highly recommended that you plan your pregnancy in advance and discuss with your doctor the advantages and possible risks of continuing treatment with lithium salts during pregnancy before becoming pregnant. If you wish to become pregnant or if you are breast-feeding, you should inform your psychiatrist to decide whether to continue treatment. If treatment is discontinued, it should be gradually reduced and supervised by your doctor |

Overall, a high level of consensus was reached on the contents to be included in the information sheet for BD patients starting lithium treatment. In the first round, there was consensus agreement on 17 of the 20 items presented to the panellists (86%). Of the remaining 3 items, 2 were agreed in the second round, leaving only one item indeterminate, therefore the final consensus reached was 95%.

In general, the items on which there were most differences (although there was also consensus in agreement) were those that gave more general information about lithium and were not specific recommendations for the patient under treatment with lithium salts. This is the case with item 16, which dealt with the discovery of lithium and was the only item that remained indeterminate. Some of the panellists’ comments on this item highlighted its lack of relevance for the patient. Finally, it was decided to follow the recommendations from the panellists’ comments and include this question in the patient information sheet, but in a shorter form. For the final draft of the information sheet, not only the comments on the above-mentioned item were considered, but also the comments of the panellists on other items on which agreement was reached, but which helped improve the clarity of the information and its accessibility for the patient.

The questions where agreement was highest – more than 95% of panellists scored in the region of agreement [7–9] – were those related to informing the patient on correct intake and follow-up of treatment and the complications they might experience. A clear understanding by the patient of the risks and benefits of their treatment – knowing the main side effects and warning signs – how to take lithium for maximum efficacy, their necessary follow-up and monitoring, and when to consult their doctor (e.g. planning a pregnancy or taking concomitant medications), are key factors in improving adherence to treatment and thus achieving greater efficacy.14,21,22,24 Therefore, it is important to provide patients with adequate information about their disease and treatment. In fact, in the case of lithium, several studies have highlighted the relationship between adherence to treatment and the patient’s knowledge of the drug.24,28

While there are clinical guidelines and consensuses aimed at professionals on the management of BD patients treated with lithium,29–35 there are no published recommendations for patients that have been developed using Delphi methodology. When searching for recommendations on the Internet, patients find information on which there may be little professional consensus, or that might even be harmful to them.29–35 While it is true that there are some hospital or autonomous community guidelines with information for patients, this is the first study to apply the Delphi methodology to develop a validated patient information sheet for lithium treatment, with the collective opinion of a group of experts from all over Spain, from different rather than individual healthcare fields. The Delphi methodology is an important tool widely used to decide the contents of questionnaires and information sheets provided to patients on various health-related issues, such as, for example, the instructions they should follow after surgery.36–38 In fact, this methodology has been used by the International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) itself to develop a guideline on the use of lithium in the management of older adult patients with bipolar disorder.39 However, this is directed at clinicians, not patients.39 In addition, in our work, the fact that the panellists were able to make comments on each item anonymously not only helped to reach a consensus in the second round, but also to improve the final wording of the patient information sheet.

A limitations of this work is that not all autonomous communities were represented, although we attempted to have a broad geographical representation of the panellists. Moreover, although experts from both hospital and ambulatory settings participated, experts from other areas such as pharmacists were not included. As this was a patient-focused sheet, it would have been valuable to have the opinion of some representatives of patients' associations to check that the patient was indeed able to understand and comprehend all the information provided.

Once the patient information sheet agreed upon in this study has been disseminated through the SEPB and implemented in routine clinical practice, it would be interesting to analyse patient satisfaction with this information and compare it with that prior to the use of the information sheet developed in this study. On the other hand, once its use is widespread, it would also be interesting to assess whether its implementation has had an impact on the patient in terms of improved adherence to lithium and even a reduction in the number of lithium toxicities.

ConclusionThrough this work, we drafted an information sheet for the TB patient on lithium treatment, with information agreed by a group of experts from different healthcare settings. Providing the patient with clear and concise information is essential at the start of treatment. It will improve adherence, improve the monitoring of adverse events, and avoid risks due to toxicity, help improve the drug’s efficacy and gain better control of the disease, and thus improve clinical evolution and prognosis.

FundingThis work received funding from the Spanish Society of Biological Psychiatry (SEPB). None of the authors or participants in the expert panel received honoraria.

AuthorshipAll the authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the paper and to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. All the authors contributed to the critical review of the draft article submitted and its final approval.

Conflict of interestsAG-P has received grants and been a consultant, advisor, or CME speaker for the following entities: Almirall, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmith-Kline, Janssen-Cilag, Ferrer, Johnson & Johnson, Lundbeck, Merck, Otsuka, Pfizer, SanofiAventis, Servier, Shering-Plough, Solvay, Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (CIBERSAM), Ministerio de Ciencia (Instituto Carlos III), Basque Government, the Stanley Medical Research Institute, and Wyeth. ABH has given lectures for Janssen, Lundbeck, Otzuka. ALMG has been a consultant or has received honoraria or research funding in the last 5 years from Forum Pharmaceuticals, Rovi, Servier, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Janssen Cilag, Pfizer and Roche, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Junta de Castilla y León and Osakidetxa. LG-R has been a consultant or has been on the panel of speakers for AstraZeneca, Janssen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Lundbeck, Pfizer, Otsuka Servier and Rovi. JMM has been a consultant or on the panel of speakers for AstraZeneca, Janssen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Lundbeck, Ferrer, Otsuka Servier and Rovi; he has received grants from the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Instituto de Salud Carlos III and CIBERSAM. VPS has been a consultant or received honoraria or funding from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Servier, Medtronic and Exeltis. JMC has been a consultant or received honoraria or funding from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka and Sanofi. He has received funding or grants for research projects from the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (Cibersam), Instituto de Salud Carlos III and Idibell. AGP has no conflict of interests to declare. CDP has been a consultant or on the panel of speakers for Janssen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Lundbeck, and Otsuka Servier; she has received grants from Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Instituto de Salud Carlos III and IDIPAZ. VBM has been a consultant or on the panel of speakers of Angelini España, Angelini Portugal, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Ferrer, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Nutrición Médica and Otsuka in the last 5 years; he has received research funding from Instituto de Salud Carlos III.

The authors would like to thank the panellists surveyed for their participation in the Delphi survey (Marta Alonso, Enric Álvarez, Purificación López, José Luis Perez de Heredia, Jerónimo Saiz, Gustavo Vázquez, Marcela Waisman, Iñaki Zorrilla, Josefina Perez Blanco, Beatriz Plasencia, Samuel Leopoldo Romero, Francisco Gotor, José Ángel Alcalá, Pilar Sierra San Miguel, Paz García Portilla, Jesús Valle, Ignacio Millán, Eduardo Jiménez, Mike Urretavizcaya Sarachag, Nuria Custal, Elena Ezquiaga, Aurelio García). We would like to thank Luzan 5 Health Consulting for methodological support and help in drafting the manuscript, Paloma Goñi Oliver in particular.

Please cite this article as: González-Pinto A, Balanzá-Martínez V, Benaberre Hernández A, Gutiérrez-Rojas L, Montes JM, Perrino CD, et al. Consenso de expertos sobre propuestas de información al paciente en tratamiento con sales de litio. Rev Psiquiatr SaludMent (Barc.). 2021;14:27–39.

![Distribution of the experts’ opinions on items where consensus was not reached in the first round (left panel) and distribution of opinions on the same items after the second round (right panel). Rating: [1–3], disagree; [4–6], neither agree nor disagree; [7–9], agree. (A) The message “Your psychiatrist is an expert in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Medical training in Spain is thoroughly regulated. Therefore trust your doctor, it is important to them to help you improve your health. Feel free to ask any questions you need” should be present on the information sheet for patients who are about to start treatment with lithium. (B) The message “A third of people have an excellent response to lithium. That means they will have very few, if any, manic or depressive episodes” should be present on the information sheet for the patient who is going to start lithium treatment. (C) I consider that general information regarding “When and where was it discovered?” should be present on the information sheet for the patient who is going to start treatment with lithium. Suggested information: “Lithium was discovered by Johann Arfvedson in 1817, in a petalite mine located on Utö Island (Sweden). In 1949, an Australian psychiatrist, John F. Cade, discovered the therapeutic effect of lithium salts in bipolar disorder”. Distribution of the experts’ opinions on items where consensus was not reached in the first round (left panel) and distribution of opinions on the same items after the second round (right panel). Rating: [1–3], disagree; [4–6], neither agree nor disagree; [7–9], agree. (A) The message “Your psychiatrist is an expert in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Medical training in Spain is thoroughly regulated. Therefore trust your doctor, it is important to them to help you improve your health. Feel free to ask any questions you need” should be present on the information sheet for patients who are about to start treatment with lithium. (B) The message “A third of people have an excellent response to lithium. That means they will have very few, if any, manic or depressive episodes” should be present on the information sheet for the patient who is going to start lithium treatment. (C) I consider that general information regarding “When and where was it discovered?” should be present on the information sheet for the patient who is going to start treatment with lithium. Suggested information: “Lithium was discovered by Johann Arfvedson in 1817, in a petalite mine located on Utö Island (Sweden). In 1949, an Australian psychiatrist, John F. Cade, discovered the therapeutic effect of lithium salts in bipolar disorder”.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/21735050/0000001400000001/v1_202103310822/S2173505021000121/v1_202103310822/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr2.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)