Psycho-COVID: Long-term effects of COVID19 pandemic on brain and mental health

Más datosCOVID-19 pandemic has affected the mental health of the general population, and in particular of health professionals. Primary care personnel are at greater risk due to being highly exposed to the disease and working regularly in direct contact with patients suffering COVID-19. However, there is not sufficient evidence on the long-term psychological impact these professionals may suffer. We aimed to explore the long-term psychological impact of COVID-19 on primary care professionals.

MethodsWe applied a two-phase design; a self-reported psychopathology screening (PHQ-9, GAD-7, ISI and IES-R) in phase-1, and a specialised psychiatric evaluation (MINI, HDRS and STAI) in phase-2 to confirm phase-1 results. Evaluations were carried at the beginning of the pandemic (May–June 2020) (n=410) and one year later (n=339). Chi-square, ANOVA and logistic regression tests were used for statistical analyses.

ResultsPrimary care professionals presented high rates of depression, anxiety and psychological distress, measured by PHQ-9, GAD-7 and IES-R respectively, during the pandemic. Depressive symptoms’ severity (PHQ-9: 7.5 vs 8.4, p=0.013) increased after one year of COVID-19 pandemic. After one year nearly 40% of subjects presented depression. Being women, having suffered COVID-19 or a relative with COVID-19, and being a front-line professional were risk factors for presenting depression and anxiety.

ConclusionPrimary Care professionals in Cantabria present a poor mental health during COVID-19 pandemic, which has even worsened at long-term, presenting a greater psychopathology severity one year after. Thus, it is critical implementing prevention and early-treatment programmes to help these essential professionals to cope with the pandemic.

La pandemia de COVID-19 ha afectado la salud mental de la población general, y en particular de los sanitarios. El personal de atención primaria tiene mayor riesgo por estar más expuesto a la enfermedad y trabajar regularmente en contacto directo con pacientes que padecen COVID-19. Sin embargo, no existe suficiente evidencia sobre el impacto psicológico a largo plazo que pueden sufrir estos profesionales. Nuestro objetivo fue explorar el impacto psicológico a largo plazo de COVID-19 en los profesionales de atención primaria.

MétodosSe aplicó un diseño en dos fases; un cribado de psicopatología a través de cuestionarios autoaplicados (PHQ-9, GAD-7, ISI e IES-R) en la fase 1, y una evaluación psiquiátrica especializada (MINI, HDRS y STAI) en la fase 2 para confirmar los resultados de la fase 1. Las evaluaciones se realizaron al inicio de la pandemia (mayo-junio de 2020) (n = 410) y un año después (n = 339). Se utilizaron pruebas de X2, ANOVA y regresión logística para los análisis estadísticos.

ResultadosLos profesionales de atención primaria presentaron índices elevados de depresión, ansiedad y malestar psicológico, medidos por PHQ-9, GAD-7 e IES-R, respectivamente, durante la pandemia. La severidad de los síntomas depresivos (PHQ-9: 7,5 vs 8,4; p = 0,013) aumentó tras un año de pandemia COVID-19. Después de un año, casi 40% de los sujetos presentaron depresión. El sexo femenino, haber padecido COVID-19 o tener un familiar con COVID-19 y ser profesional de primera línea fueron factores de riesgo para presentar depresión y ansiedad.

ConclusionesLos profesionales de Atención Primaria en Cantabria presentaron una mala salud mental durante la pandemia de COVID-19, la cual además empeoró a largo plazo, presentando una mayor gravedad los síntomas un año después. Por lo tanto, es fundamental implementar programas de prevención y tratamiento temprano para ayudar a estos profesionales esenciales a hacer frente a la pandemia.

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by SARS-CoV-2 virus, has rapidly spread world-wide since the pandemic was declared in the early months of 2020. Given the highly contagious capacity of this new SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, WHO recommended limiting human-to-human transmission by reducing secondary infections among close contacts and healthcare workers, preventing transmission amplification events, and preventing further international spread.1 The SARS-CoV-2 virus is producing a serious impact on physical health and it entails a significant risk for life with an observed excess mortality.2 Apart from the serious threats to people's physical health and lives that is being caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the fears, uncertainties and strict measures of quarantine and home-confinement (leading to people isolation) can have a detrimental impact on mental health and would be contributing to an increasing incidence of mental health problems. Several studies have shown from the early phases of the pandemic a wide psychological impact in the general population3–5 in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic. In Spain high rates of depressive and anxiety symptoms were also reported at the beginning of the pandemic,6 having even increased among general population during the pandemic.7

Health professionals are at particular high risk of suffering a psychological effect from the pandemic.8 For instance, a recent study reported that among 994 medical staff working in Wuhan, the majority experienced psychological impact measured by the PHQ-9 scale.9 In the same line, Lai and colleagues10 in their cross-sectional, survey-based study on 1257 healthcare workers, observed that a substantial proportion of participants reported symptoms of depression (50.4%), anxiety (44.6%), insomnia (34.0%), and distress (71.5%). Similarly, in Spain, healthcare staff reported symptoms of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).11 However, despite being one of the most affected countries by the pandemic, Spain seemed to have a lower rate of medical staff with psychological problems, according to a survey-based study with healthcare workers of eight different European countries.12

Several risk factors for presenting more severe psychological symptoms have been identified in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic, such as gender (women) and working at the healthcare frontline and in high-exposure units.9,10,13,14 The gender differences are in line with those observed in the general population where female citizens reported higher degrees of the psychological impact of the outbreak, stress, anxiety, and depression.5 Similarly in Spain it has been described an association between being women or working at the front-line, with an increased risk of having a greater psychological impact.11 Age was also described as a risk factor, where younger professionals were the most affected by these symptoms.15

The main objective of this study was to evaluate the psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic in public health care workers in Primary Care in Cantabria. Secondly, we aimed to explore if there are specific risk factors for a greater psychological impact from COVID-19 exposure. Taking into account the previously described scientific evidence, we hypothesised that primary care health professionals will present psychological symptoms, such as anxiety, depression, insomnia or post-traumatic symptoms, in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, gender (women), age (younger) and being first-line health professionals will convey a greater risk of presenting a psychological impact.

Material and methodsThis work has been carried out in Cantabria (northern Spain), between May 2020 and June 2021.

DesignWe designed a prospective longitudinal two-phase study.16,17 The phase 1 consisted in a wide (regional level) screening (self-applied scales) of psychological symptoms among Primary Care professionals. This screening was carried out at baseline, between May and June 2020, and one year later, between May and June 2021. The phase 2 consisted in a more detailed and specialised mental health evaluation of a sub-sample of the study population at baseline.

Study population and survey processThe study was focused on health professionals working at Primary Care in Cantabria (Servicio Cántabro de Salud). After getting institutional approval, the survey was sent to Primary Care personnel through email. A specifically short and quick survey was designed to facilitate completing it. Data from completed surveys were exported to the study database and stored at the IDIVAL centre. After completing the phase-1 survey (screening) subjects were invited to participate in the phase-2 of the study, a specialised mental health examination through personal interviews with trained psychiatrists. Finally, and in order to explore the long-term psychological impact of the pandemic, the Phase 1 (screening survey) was again repeated one year later; subjects who have respond to baseline surveys was invited to participate 1 year later.

All subjects gave written informed consent before participating in the study (for both phases of the study). The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Cantabria (CEIm of Cantabria). Subjects’ data was managed confidentially following national and international regulations.

Clinical evaluationPhase 1: screening through self-reported surveyThe phase 1 of the study consisted in a self-reported survey that included a mental health evaluation and an ad-hoc designed questionnaire on socio-demographic and occupational characteristics, a COVID-19 exposure and self-perceived health-related quality of life, on a Likert-type scale (between 1 – minimum- and 7 – highest-scores).

Mental health status was assessed through a set of validated self-rated scales. The 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to evaluate severity of depressive symptoms: minimal/no depression (0–4), mild depression (5–9), moderate depression (10–14), moderately severe depression (15–19) or severe depression (20–27).18 “Probable depression” was defined as a score of 10 or greater on the PHQ-9.19 The 7-item Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) to evaluate anxiety severity: minimal/no anxiety (0–4), mild anxiety (5–9), moderate anxiety (10–14), or severe anxiety (15–21).20 “Probable anxiety” was defined as a score of 10 or greater on the GAD-7.21 The 7-item Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) measures insomnia severity: normal (0–7), subthreshold (8–14), moderate insomnia (15–21), or severe insomnia (22–28).22 And the 22-item Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) evaluates psychological distress to a specific stressful life event (the occurrence of COVID-19 in this case): subclinical (0–8), mild distress (9–25), moderate distress (26–43), and severe distress (44–88).23 In this study scoring over 33 was considered as a cut off for a “probable PTSD case or psychological distress”.24

Suicidality was assessed through the item 9 of the PHQ-9 scale, which evaluates passive thoughts of death or self-injury within the last two weeks, and is often used to screen depressed patients for suicide risk.25

Phase 2 – Specialised mental health evaluationThe second phase of the study consisted in a specialised mental health evaluation carried out by experienced psychiatrists. This mental health assessment included the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview26 Spanish version 5.0.0; the MINI is a brief structured diagnostic interview that explores the main psychiatric disorders (from DSM-IV and CIE-10) allowing its identification and diagnostic orientation, while presenting good psychometric properties (inter-observer reliability-kappa value 0.75, test–retest reliability 0.75).

To evaluate depression severity we used the 17-item version of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS).27 Each item is rated between 0 and 2 points in some cases, and between 0 and 4 in others, ranging the total score between 0 and 52 points. Different specific indices have been defined: (a) Melancholy index, made up of items 1 (depressed mood), 2 (feeling of guilt), 7 (work and activities), 8 (inhibition), 10 (psychic anxiety) and 13 (general somatic symptoms); (b) Anxiety index, made up of items 9 (agitation), 10 (psychic anxiety) and 11 (somatic anxiety); and (c) Sleep disturbance index, formed by the three items referring to insomnia (i.e.: 4, 5, 6). The HDRS has good psychometric properties, with good internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha between 0.76 and 0.92), intra-class correlation coefficient of 0.92, and inter-observer reliability between 0.65 and 0.9.

Finally, we used the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) to assess anxiety.28 The STAI assess anxiety as a state (momentary, transitory) and anxiety as a trait (as a more stable condition). It is made up of 40 items divided into 2 subscales: trait and state, with Likert-type responses from 0 to 3.

Previous personal psychiatric history and prescription of psychiatric treatments, and substance use (tobacco and alcohol) were explored specifically during this clinical interview.

StatisticsChi-square and ANOVA analyses were performed to compare qualitative and quantitative variables between the two groups. Binary logistic regression was run to determine the effect of gender (women), age, being first-line health worker, and COVID-19 direct exposure (having had COVID-19 and/or having had a relative with COVID-19) on presenting a probable depression (PHQ-9≥10) or anxiety (GAD-7≥10). The Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analyses. All statistical tests were two-tailed and significance was determined at the 0.05 level.

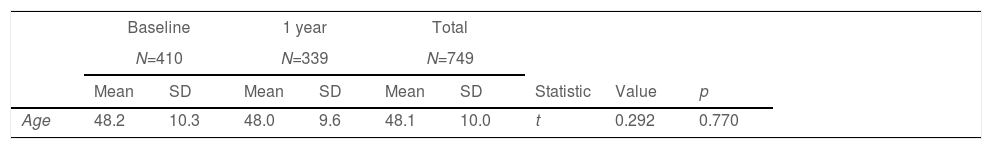

ResultsEnrolment and sample descriptionA total of 410 healthcare workers participated in this survey at baseline, and 339 one year after (Table 1), almost reaching the 20% of the target population. At both time-points, a majority of participants were women (72.9 and 71.9%, respectively). Most of the subjects were Medical doctors (43.6 and 47.5%) or nurses (27.9% and 27.1%) and they majorly work in primary care teams (57.1% and 47.2%) while 33.6% work in primary care emergency walk-in teams. The mean age of the study sample was 48 years at both time-points. As shown in Table 1 we found no significant differences in the sociodemographic and occupational characteristics between both time-points.

Socio-demographic and occupational characteristics of the study samples.

| Baseline | 1 year | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=410 | N=339 | N=749 | |||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Statistic | Value | p | |

| Age | 48.2 | 10.3 | 48.0 | 9.6 | 48.1 | 10.0 | t | 0.292 | 0.770 |

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (women) | 299 | 72.9 | 244 | 71.9 | 543 | 72.5 | X2 | 0.062 | 0.803 |

| Civil status | Fisher | 3.719 | 0.289 | ||||||

| Single | 75 | 18.4 | 45 | 13.3 | 120 | 16.1 | |||

| Married or couple | 296 | 72.5 | 264 | 77.9 | 560 | 75.0 | |||

| Divorced or widowed | 37 | 10 | 30 | 8.9 | 67 | 9 | |||

| Educational level | X2 | 1.702 | 0.427 | ||||||

| Secondary education or lower | 45 | 11 | 31 | 9.2 | 76 | 10.2 | |||

| University education | 363 | 89.0 | 308 | 90.9 | 671 | 89.8 | |||

| Occupation | X2 | 8.540 | 0.481 | ||||||

| Doctor | 178 | 43.6 | 161 | 47.5 | 339 | 45.4 | |||

| Nurse | 114 | 27.9 | 92 | 27.1 | 206 | 27.6 | |||

| Administrative | 35 | 8.6 | 29 | 8.6 | 64 | 8.5 | |||

| Emergency sanitary technician | 27 | 6.6 | 28 | 8.3 | 55 | 7.4 | |||

| Physiotherapist | 16 | 3.9 | 14 | 4.1 | 30 | 4.0 | |||

| Midwife | 17 | 4.1 | 8 | 2.4 | 25 | 3.4 | |||

| Social worker | 12 | 2.9 | 5 | 1.5 | 17 | 2.3 | |||

| Cleaning service | 9 | 2.2 | 2 | 0.6 | 11 | 1.5 | |||

| Place of work | X2 | 7.760 | 0.051 | ||||||

| Primary care team | 233 | 57.1 | 160 | 47.2 | 393 | 52.6 | |||

| Primary care emergency team | 125 | 30.6 | 122 | 36.0 | 247 | 33.1 | |||

| 061 Ambulance service team | 26 | 6.4 | 29 | 8.6 | 55 | 7.4 | |||

| Other | 24 | 5.9 | 28 | 8.3 | 52 | 7.0 | |||

| Residential area | X2 | 1.414 | 0.814 | ||||||

| Urban area (>10,000 inhabitants) | 212 | 52.0 | 177 | 52.2 | 389 | 52.1 | |||

| Small urban area (2,000–10,000) | 131 | 32.1 | 104 | 30.7 | 235 | 31.5 | |||

| Rural area (<2,000 inh.) | 65 | 15.9 | 58 | 17.1 | 123 | 16.4 | |||

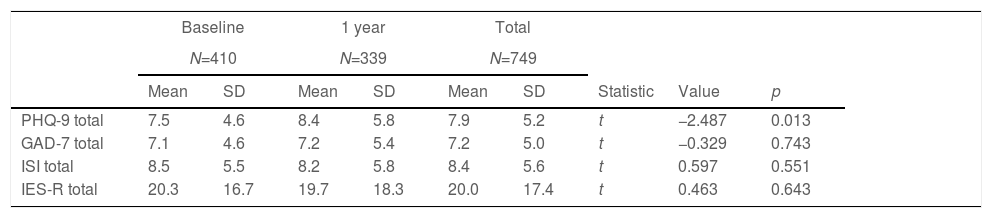

Participants reported important depressive symptomatology, with 30% of them reporting a score of probable depression at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 2). This rate significantly increased after 1 year, reaching up to 39% of the participants. This change was in parallel with a significant increase in the mean PHQ-9, from 7.5 to 8.4 (p=0.013). We observed no significant changes in the mean GAD-7 or in the proportion of subjects reaching a score suggestive of “probable anxiety disorder”, which remained around 30% of the study population. Insomnia, as reported through the ISI, was very common among primary care health workers, although we found no significant differences after 1 year of COVID-19 pandemic. Mean IES-R score did not differ at 1 year compared to baseline self-evaluation. Despite this, it is noteworthy to highlight that around 20% of primary care professionals reached a scoring suggestive of “probable PTSD” at both time-points.

Long-term differences in self-reported psychological symptoms among primary care health professionals in Cantabria.

| Baseline | 1 year | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=410 | N=339 | N=749 | |||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Statistic | Value | p | |

| PHQ-9 total | 7.5 | 4.6 | 8.4 | 5.8 | 7.9 | 5.2 | t | −2.487 | 0.013 |

| GAD-7 total | 7.1 | 4.6 | 7.2 | 5.4 | 7.2 | 5.0 | t | −0.329 | 0.743 |

| ISI total | 8.5 | 5.5 | 8.2 | 5.8 | 8.4 | 5.6 | t | 0.597 | 0.551 |

| IES-R total | 20.3 | 16.7 | 19.7 | 18.3 | 20.0 | 17.4 | t | 0.463 | 0.643 |

| N | % | N | % | N | % | Statistic | Value | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 | X2 | 17.930 | 0.003 | ||||||

| No depression – minimal | 123 | 30.1 | 105 | 30.9 | 228 | 30.5 | |||

| Mild depression | 161 | 39.5 | 102 | 30.1 | 263 | 35.2 | |||

| Moderate depression | 88 | 21.6 | 77 | 22.7 | 165 | 22.1 | |||

| Moderately severe depression | 32 | 7.8 | 38 | 11.2 | 70 | 9.4 | |||

| Severe depression | 4 | 1.0 | 17 | 5.0 | 21 | 2.8 | |||

| Probable depression (PHQ-9≥10) | 124 | 30.4 | 132 | 38.9 | 256 | 34.3 | X2 | 6.003 | 0.014 |

| Probable anxiety (GAD-7≥10) | 124 | 30.4 | 112 | 33.0 | 236 | 31.6 | X2 | 0.600 | 0.439 |

| ISI | X2 | 2.595 | 0.458 | ||||||

| No insomnia | 194 | 47.5 | 162 | 47.8 | 356 | 47.7 | |||

| Insomnia, subclinical | 145 | 35.5 | 122 | 36.0 | 267 | 35.7 | |||

| Insomnia, moderate severity | 64 | 15.7 | 46 | 13.6 | 110 | 14.7 | |||

| Insomnia, severe | 5 | 1.2 | 9 | 2.7 | 14 | 1.9 | |||

| IES-R | X2 | 2.198 | 0.532 | ||||||

| Absence | 257 | 63.0 | 225 | 66.4 | 482 | 64.5 | |||

| Clinical issue | 65 | 15.9 | 44 | 13.0 | 109 | 14.6 | |||

| Probable PTSD | 14 | 3.4 | 8 | 2.4 | 22 | 2.9 | |||

| Severe problem | 72 | 17.6 | 62 | 18.3 | 134 | 17.9 | |||

| Probable PTSD case or psychological distress (IES-R>33) | 81 | 19.9 | 68 | 20.1 | 149 | 19.9 | X2 | 0.005 | 1.000 |

Abbreviations: PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnair-9; GAD-7: Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7; ISI: Insomnia Severity Index; IES-R: Impact of Event Scale-Revised; PTSD: posttraumatic stress disorder.

Regarding suicidality, the proportion of subjects having passive suicidal thoughts increased from baseline to 1-year follow-up (7.1% vs 11.2%, x2=3.815, p=0.051). At baseline, 27 participants (7.1%) reported having had thoughts of death or self-injury in the previous 2 weeks “several days” (5.4%), “more than half the days” (1.5%), or “nearly every day” (0.2%). While at 1-year follow-up 38 subjects (11.2%) informed having passive suicidal thoughts in the last 2 weeks “several days” (8.0%), “more than half the days” (1.5%), or “nearly every day” (1.7%).

Risk factors for self-reported psychological impact during COVID-19Associations analyses showed a significant relation between presenting a PHQ-9 of probable depression (10 or above) with gender (39% of women vs 21.8% of men; X2=19.496, p<0.001), being first-line health worker (35.4% versus 25.3 of non-first line professionals; X2=3.335, p=0.085) and having suffered COVID-19 (52.6% vs 32.8%; X2=9.236, p=0.003). Age was not significantly associated with presenting depression (p>0.05). Similarly, we observed a significant association between reporting a probable anxiety disorder (GAD-7 of 10 or above) and gender (34.9% of women vs 22.8% of men; X2=10.140, p=0.001), being first-line health worker (32.8% versus 21.7% of non-first line professionals; X2=4.240, p=0.045), having suffered COVID-19 (45.6% vs 30.4%; X2=5.613, p=0.025) and having a close relative who had suffered COVID-19 (43.8% vs 30.5%; X2=4.787, p=0.035). We observed a tendency towards statistical significance when exploring the associations between age and anxiety (F=3.815; p=0.051); those subjects with anxiety (GAD-7≥10) were younger (mean age 47 years) than those without anxiety (mean age 48.6 years).

Logistic regression analyses showed gender (women) (b=0.914, z=4.686, p<0.001), having suffered COVID-19 (b=0.895, z=0.019, p=0.005) and being first-line professionals (b=0.672, z=2.432, p=0.015) as predictive factors for “probable depression”. Similarly, the results showed that gender (women) (b=0.914, z=4.686, p<0.001), age (b=−0.017, z=−2.115, p=0.034) and being first-line professionals (b=0.788, z=2.713, p<0.007) were predictive factors for “probable anxiety”. However, both models showed a small R2 Nagelkerke (0.065 and 0.053 respectively), not allowing a full explanation of the variability.

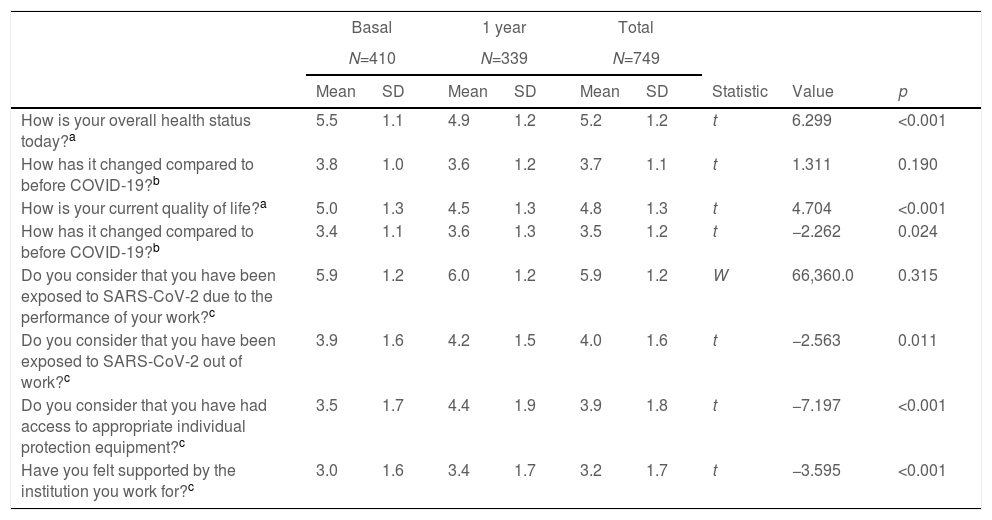

Health workers’ perceived quality of life and other self-perceived reports related to the COVID-19 pandemicAs shown in Table 3, the mean self-perceived quality of life and health status were good (above 4=“normal”). However, these items were scored significantly lower after 1 year of the pandemic, reflecting a statistically significant decrease in the self-perceived health status and quality of life of health workers in the study. In line with this, primary care professionals perceived that their health status and quality of life had worsened compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants also reported a perception of having been clearly exposed to SARS-CoV-2 at their work. Participants perceived not having had access to the appropriate individual protection equipment and having received poor institutional support during the pandemic. However, these perceptions significantly improved 1 year after. It is noteworthy the significant increase of primary care professionals having suffered from COVID-19 after 1 year of the pandemic breakout.

Long-term differences in quality of life and other self-reported experiences related to COVID-19 pandemic in primary care professionals in Cantabria.

| Basal | 1 year | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=410 | N=339 | N=749 | |||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Statistic | Value | p | |

| How is your overall health status today?a | 5.5 | 1.1 | 4.9 | 1.2 | 5.2 | 1.2 | t | 6.299 | <0.001 |

| How has it changed compared to before COVID-19?b | 3.8 | 1.0 | 3.6 | 1.2 | 3.7 | 1.1 | t | 1.311 | 0.190 |

| How is your current quality of life?a | 5.0 | 1.3 | 4.5 | 1.3 | 4.8 | 1.3 | t | 4.704 | <0.001 |

| How has it changed compared to before COVID-19?b | 3.4 | 1.1 | 3.6 | 1.3 | 3.5 | 1.2 | t | −2.262 | 0.024 |

| Do you consider that you have been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 due to the performance of your work?c | 5.9 | 1.2 | 6.0 | 1.2 | 5.9 | 1.2 | W | 66,360.0 | 0.315 |

| Do you consider that you have been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 out of work?c | 3.9 | 1.6 | 4.2 | 1.5 | 4.0 | 1.6 | t | −2.563 | 0.011 |

| Do you consider that you have had access to appropriate individual protection equipment?c | 3.5 | 1.7 | 4.4 | 1.9 | 3.9 | 1.8 | t | −7.197 | <0.001 |

| Have you felt supported by the institution you work for?c | 3.0 | 1.6 | 3.4 | 1.7 | 3.2 | 1.7 | t | −3.595 | <0.001 |

| N | % | N | % | N | % | Statistic | Value | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you been sick from COVID-19? (Yes) | 15 | 3.7 | 42 | 12.4 | 57 | 7.6 | X2 | 19.943 | <0.001 |

| Have you lived with COVID-19 patients? (Yes) | 13 | 3.2 | 51 | 15.0 | 64 | 8.6 | X2 | 33.235 | <0.001 |

We observed a significant association between presenting depression or anxiety and most of quality of life and self-perceived experiences’ variables. Thus, those subjects reporting depression or anxiety, presented a significantly poorer health-related quality of life than those without depression or anxiety (see Supplementary material 1). Moreover, depression and anxiety were significantly associated with a perception of poorer institutional support and poorer access to appropriate individual protection equipment.

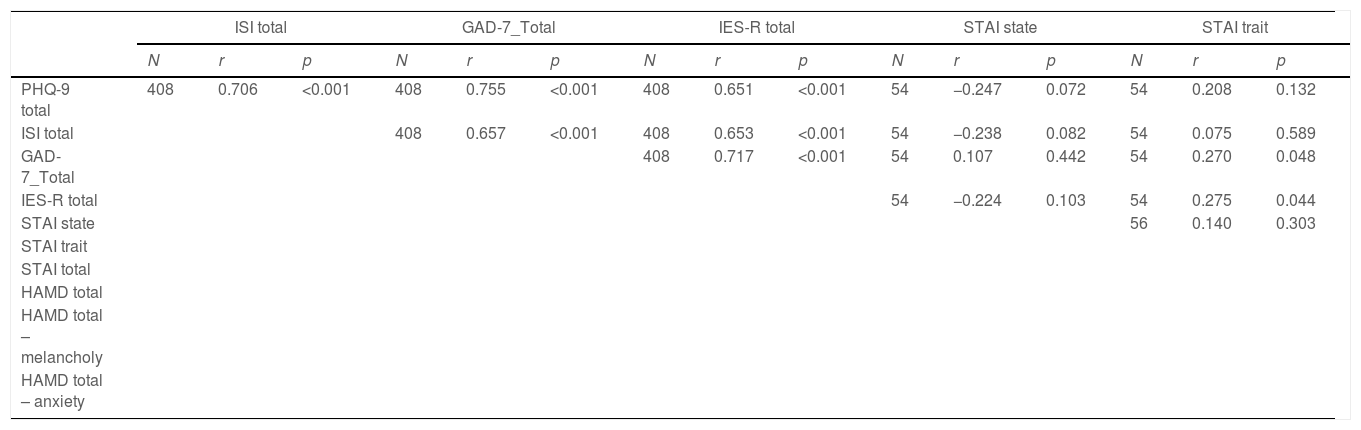

Phase-2 results and correlations between phase 1 and phase 2 evaluationsPhase-2 of the study was carried out at baseline, on a representative subgroup of 57 subjects (Supplementary material 2). We observed moderate correlations between the specialised psychopathological evaluations from phase-2 and the self-reported psychological symptoms from phase-1 (Table 4). Seventeen (29.8%) participants in the phase-2 reported having a past history of psychiatric issues. Based on the MINI structured interview 25% of subjects presented at baseline (phase 2) a diagnosis of depression and/or anxiety disorder, whereas only 8.8% (n=5) admitted having sought help in the previous weeks. 28.1% (n=16) were on psychopharmacological treatment (4 on antidepressants, 3 on anxiolytics and 9 on hypnotic medications) and 3 (5.3%) on psychological treatment. Regarding substance use, 17.5% of participants reported smoking tobacco and 49.1% having consumed alcohol in the previous year. In comparison to pre-pandemic use, 50% had increased during the COVID-19 pandemic the amount of tobacco smoked, and 28.1% reported having increased the alcohol used.

Correlation analyses between phase 1 and phase 2 evaluations (self-reported versus psychiatrists evaluations) of Primary Care professionals in Cantabria during the COVID-19 pandemic.

| ISI total | GAD-7_Total | IES-R total | STAI state | STAI trait | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | r | p | N | r | p | N | r | p | N | r | p | N | r | p | |

| PHQ-9 total | 408 | 0.706 | <0.001 | 408 | 0.755 | <0.001 | 408 | 0.651 | <0.001 | 54 | −0.247 | 0.072 | 54 | 0.208 | 0.132 |

| ISI total | 408 | 0.657 | <0.001 | 408 | 0.653 | <0.001 | 54 | −0.238 | 0.082 | 54 | 0.075 | 0.589 | |||

| GAD-7_Total | 408 | 0.717 | <0.001 | 54 | 0.107 | 0.442 | 54 | 0.270 | 0.048 | ||||||

| IES-R total | 54 | −0.224 | 0.103 | 54 | 0.275 | 0.044 | |||||||||

| STAI state | 56 | 0.140 | 0.303 | ||||||||||||

| STAI trait | |||||||||||||||

| STAI total | |||||||||||||||

| HAMD total | |||||||||||||||

| HAMD total – melancholy | |||||||||||||||

| HAMD total – anxiety | |||||||||||||||

| STAI total | HAMD total | HAMD total – melancholy | HAMD total – anxiety | HAMD total – insomnia | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | r | p | N | r | p | N | r | p | N | r | p | N | r | p | |

| PHQ-9 total | 54 | 0.006 | 0.965 | 55 | 0.517 | <0.001 | 55 | 0.484 | <0.001 | 55 | 0.450 | 0.001 | 55 | 0.326 | 0.015 |

| ISI total | 54 | −0.087 | 0.530 | 55 | 0.441 | <0.001 | 55 | 0.369 | 0.006 | 55 | 0.238 | 0.081 | 55 | 0.469 | <0.001 |

| GAD-7_Total | 54 | 0.265 | 0.053 | 55 | 0.477 | <0.001 | 55 | 0.411 | 0.002 | 55 | 0.457 | <0.001 | 55 | 0.263 | 0.052 |

| IES-R total | 54 | 0.070 | 0.615 | 55 | 0.339 | 0.011 | 55 | 0.378 | 0.004 | 55 | 0.402 | 0.002 | 55 | 0.161 | 0.241 |

| STAI state | 56 | 0.681 | <0.001 | 56 | −0.075 | 0.581 | 56 | −0.160 | 0.240 | 56 | 0.036 | 0.790 | 56 | −0.004 | 0.974 |

| STAI trait | 56 | 0.820 | <0.001 | 56 | 0.099 | 0.468 | 56 | 0.288 | 0.032 | 56 | 0.309 | 0.020 | 56 | −0.054 | 0.690 |

| STAI total | 56 | 0.030 | 0.828 | 56 | 0.121 | 0.376 | 56 | 0.250 | 0.063 | 56 | −0.043 | 0.754 | |||

| HAMD total | 57 | 0.835 | <0.001 | 57 | 0.711 | <0.001 | 57 | 0.629 | <0.001 | ||||||

| HAMD total – melancholy | 57 | 0.640 | <0.001 | 57 | 0.277 | 0.037 | |||||||||

| HAMD total – anxiety | 57 | 0.234 | 0.080 | ||||||||||||

Abbreviations: PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index; GAD, General Anxiety Disorder; IESR, Impact of Event Scale-Revised; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale.

Our study shows high rates of depression, anxiety, insomnia and psychological distress, measured by PHQ-9, GAD-7, ISI and IES-R respectively, during the first months of the pandemic, in primary care professionals. This self-reported psychopathology correlated with a specialised clinical evaluation carried out in a representative subsample of participants. One year later, we observed a significant increase in the mean score in the depression scale PHQ-9 together with a significant increase in the percentage of subjects with a PHQ-9 score suggestive of depression, reaching up to 40% of the participants. The scoring in all the other scales increased, although the differences did not reach statistical significance.

These results are in line with previous evidence showing that health care professionals have experienced during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic, a clinically relevant psychological impact, measured by self-applied scales.9,10 These results have been also seen in Spain where healthcare staff reported symptoms of PTSD, stress, anxiety or depression.11,12 Similarly, previous stressful epidemics, such as the SARS-CoV in 2003, the Ebola (2014) or the MERS-CoV outbreak in 2015, already highlighted that healthcare professionals where specially at high risk of developing psychological symptoms and mental health disorders such as anxiety, depression and PTSD.13,29–31

It is important to acknowledge that the psychological impact produced by previous community crises precipitated new psychiatric symptoms in people without mental illness and also aggravated the condition of those with pre-existing mental illness.32 Thus, the psychological impact has been reflected in the incidence of psychiatric morbidities varying from depression, anxiety and PTSD symptoms, to delirium, psychosis and even suicidality.32 This is also important since common mental health disorders, such as anxiety and depression, are known to have detrimental effects on other (physical) health measures.33

As a result of these effects, it has been suggested that in the forthcoming months, the health system will suffer a shortage of health professionals due to mental exhaustion.34 Moreover, these mental health problems among health professionals could also affect their clinical performance and decision making ability, jeopardising the health system capacity of fighting the COVID-19 pandemic.35 Ultimately, psychological exhaustion seemed to directly affect the professionals’ quality of life, their level of satisfaction and their working performance while working.11 In our study, participants reported having mean scores in self-perceived health status and quality of life just above “normal” (4 in a 1–7 Likert-type scale) at both time points, but with a significantly decrease in both perceptions after 1 year follow-up. Moreover, participants reported that their health status and quality of life had become worse compared to how it was before the COVID-19 pandemic. This poor self-perceived health status and quality of life were associated with a poorer mental health, with more severe anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Several individual risk factors for a greater psychological impact have been identified; gender (women), younger age and working at the frontline or in high-exposure units.9,10,13,14 Although healthcare workers from none-high exposure units may also present psychological distress during the pandemic,36 probably through vicarious traumatisation.37 Similar results have been found in Spain, where being women, younger or working at the front-line, were associated with a greater psychological impact.11,15 Our results are partially in line with these previous evidences; in our sample, being women and working in front-line position were risk factors for presenting depression and anxiety. However, and contrary to what we expected, younger age presented only a weak association with anxiety. Interestingly, we did find significant associations between a greater psychological impact (depression or anxiety) and having suffered COVID-19 or having a family member with COVID-19.

Isolation and the lack of social support could be determining factors in coping with this traumatic event.13,38 The high pressure, including overwork, frustration, discrimination, a high risk of infection, but also the fear of being infected and infecting others, were underlying factors of a greater risk or presenting stress, anxiety and depressive symptoms in healthcare professionals.30,35,39 Other factors influencing the psychological distress are those related to the efficacy of the health system during the pandemic, such as the availability of local medical resources, efficiency of the regional public health system, and prevention and control measures taken against the epidemic situation.4 One of the main complaints raised by health professionals in this respect is the lack of appropriate training for providing mental health care in this context.40 On the contrary, the perception of an effective coordination and access to safe environment and individual protection equipment has been identified as protective factors; inadequate protection from contamination has been related to mental health problems such as stress, anxiety, depressive symptoms, and insomnia,35 while professionals who had access to well-equipped and structured environment showed a better psychological adaptation to previous epidemics.13 In this sense, we observed that those primary care professionals with greater severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms significantly perceived a poorer institutional support and deficient access to individual protection equipment during the pandemic; although a causative relation between these factors cannot be established from our data, and there may be a bidirectional effect.

Several limitations must be highlighted in our study. The main limitation is that since we lack a psychological evaluation from a pre-pandemic period, we cannot infer a causal relation between the COVID-19 pandemic and the observed psychological symptoms among the participants. However, we cannot obviate the significant impact the COVID-19 pandemic has entailed, with a clear effect on mortality, global health, health systems’ workload, and social changes including isolation and loneliness, all of them risk factors for presenting a worse mental health. Therefore, we could assume that the poor mental health observed among primary care health workers in Cantabria in this study, during the first stages of COVID-19 pandemic, was at least partially, related to the pandemic itself.

At 1-year follow-up, we sent the electronic survey to the same group of primary care health workers subjects, asking them to respond to it only if having done so at baseline, in an attempt to evaluate the same individuals at both time-point. However, since the electronic surveys were anonymous, we cannot assure that we evaluated the same sample of individuals at both time-points. Despite of this, both samples were similar in all the socio-demographic and occupational characteristics. Other limitations are that the study followed a non-probabilistic “snowball sampling” and the limited sample size. However, it is noteworthy that the study sample was almost the 20% of the target population. Finally, suicidality was measured by means of the PHQ-9 item 9, which evaluates passive thoughts of suicide. Although this is a way of evaluating risk of suicide, it would be recommended using a more specific and complete tool for suicide risk (e.g.: the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale). Similarly, a better description and analysis of substance use would be desirable. Further studies should look into other relevant aspects in the evaluation of the psychological impact of health workers, not included in the present study, such as burnout syndrome. On the other hand, the study has some strengths. The main strength is its two-phase design which provides an empirical validation of the self-reported symptoms (phase 1); previous studies have been exclusively survey-based, and although the self-reported scales they used have been previously validated, they could have missed some clinical information. Therefore, we provide a “clinical validation” of our self-reported evaluation (phase-1) through specialist evaluations carried out by psychiatrists in the phase-2 of the study. We included in the study all the professions working at primary care in Cantabria, and not only doctors and nurses as in other studies. Thus, the data is more representative of the study population. Finally the study includes a subject-centred approach, with measures of self-perceived quality of life, exposure to SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 and other self-perceived experiences related to the pandemic, that have not been extensively explored in previous studies.

The study contributes to the evidence of an association between the COVID-19 pandemic and mental health on primary care health professionals, and sheds light on the possible risk factors associated with a greater psychological repercussion of the pandemic. Thus, it improves the knowledge for the development and implementation of prevention and early intervention programmes to alleviate the psychological distress of these at-risk essential workers.41 In this sense, a wide range of psychological interventions have been implemented and made available to health professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic,42 although only a few have shown some efficacy in reducing the psychological distress and psychopathology associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.43

ConclusionsWe observed a temporal relation between COVID-19 pandemic and a significantly poor mental health among primary care professionals in Cantabria, which has even significantly worsened at long-term, presenting a greater symptoms’ severity one year after. These findings are clinically relevant since they provide further evidence on the possible long-term psychopathological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on primary care health professionals. It also sheds light on the possible risk factors that might be associated with a greater psychological repercussion of the pandemic.

Funding disclosuresThe present study was carried out at the Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla, University of Cantabria, Santander, Spain, under the following grant support: Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria ValdecillaPRIMVAL20/08, INT/A21/10 and INT/A20/04.

Conflict of interestThe authors report no conflicts of interest in producing this manuscript.

The authors wish to thank all the colleagues from Primary Care network in Cantabria (Servicio Cántabro de Salud) for their participation in the study, the Primary Care Directorate for supporting the study, and the Colegio Oficial de Médicos de Cantabria for helping to disseminate the surveys.