Cognitive reserve (CR) has recently been considered a key factor in the onset of a first episode of psychosis (FEP). However, the differences in CR in FEP patients according to sex have not yet been investigated.

Material and methodsCR was estimated among 443 FEP patients (246 men and 197 women) and 156 healthy controls (96 men and 60 women) by using the proxies premorbid IQ, years of education and employment status. A neuropsychological battery was administrated to measure neurocognitive specific domains. Analyses of variance were used to make comparisons between groups.

ResultsFEP women had greater CR than FEP men. This circumstance was not observed in healthy controls. Among the group of patients with low CR, FEP women outperformed FEP men in the cognitive domains verbal memory and processing speed. Meanwhile, among the FEP patients with high CR, men showed better performance in attention than women.

ConclusionsDifferences in CR observed between FEP men and women could be related to a number of specific factors, such as, age at illness onset, education level, and variability in performance in verbal memory, processing speed, and attention domains. These results provide background information about CR in FEP patients that will be useful in the design of sex specific cognitive remediation interventions.

The concept of cognitive reserve (CR) was defined as the ability of the brain to cope with deficits produced by pathologies.1 It entails the use of alternating networks, in a manner both flexible and efficient, that allow patients to increase their abilities and face their cognitive limitations through compensation.2

At first, CR was studied in neurodegenerative conditions with a particular focus on Alzheimer's disease. In this context, participants with high previous educational levels had advantages over the cognitive deficits of the disease,3 while previous functionality, intelligence, and physical activity acted as protective factors in terms of the onset of the disease.4 Subsequently, the study of CR was extended to other psychopathologies. What resulted was the discovery that CR influenced the pathology of a disorder, such that participants’ expressions of symptoms and functionality were strong predictors of its emergence and trajectory. In short, participants with lower levels of CR showed greater vulnerability for the development of a disorder.5

In the field of schizophrenia, the literature has shown that CR is relevant to the cognitive domains, specifically when considering sex. Low levels of intelligence have been shown to be a risk factor for the development of the disorder.5,6 CR has shown predictive capacity in both working memory7 and attention domains,8–10 but not in verbal memory or flexibility.11 Compared to women, men have shown earlier disease onsets, lower educational and socioeconomic levels, along with worse prognoses of the disease; but, they have also shown higher performance in the domains of visual memory, reaction times and executive functions.12 Women, in contrast, have shown preserved IQs and higher educational levels,13 along with better performance in verbal memory12 and better baseline and longitudinal functioning.14 This could support the fact that women presented higher levels of CR at illness onset.

Research on CR in schizophrenia has also found indications of its relevance to the emergence and subsequent trajectory of the disease. For instance, it was predictive of subsequent functioning15 and use of social skills after the emergence of schizophrenia.16 Specifically, investigations of First Episode of Psychosis (FEP) have indicated that CR can be considered a key factor at illness onset and a protective factor against cognitive deterioration.17 For these reasons, it is worth considering CR during the development of psychosis prior to illness onset, particularly for the establishment of interventions that prevent neurocognitive disorders. Likewise, CR should be considered in treatments for individuals over the duration of their illness.

Understanding the relationship between CR and the cognitive domains is of vital importance in establishing adequate treatments; for instance through the use of preventive interventions, such as the Cognitive Reserve EnhAncement ThErapy (CREATE),18 in at-risk populations. Furthermore, there is a lack of evidence on the diversity of the performance of cognitive tasks between women and men in the research of FEP, because no research has been found that directly relates CR and the differences in cognitive domains according to sex in FEP patients.

For this reason, the present research aims to find differences in the estimation of CR according to sex and specifically the differences in cognitive domains based on sex and the estimated CR. We hypothesized that: (1) FEP women would have a higher CR than FEP men; (2) FEP women with higher CR would present better performance in the domain of verbal memory. Finding these results would be important in establishing treatments that are more personalized, particularly because they would provide an a priori probability of the cognitive domains to be most affected for either men or women.

Material and methodsParticipantsThe study sample comes from a large epidemiological, longitudinal intervention program on first-episode psychosis (PAFIP) at the Marqués de Valdecilla University Hospital (Santander, Spain). Ethical approval was obtained from the local Ethics Committee. A more detailed description of PAFIP has been previously given.19,20

The patient group consisted of 443 medication-naive participants included in PAFIP recruited between February 2001 and February 2011. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after a complete description of the study. The patients met the following criteria: (1) 15–60 years of age; (2) lived within the catchment area; (3) were experiencing a first episode of psychosis; (4) had no prior treatment with antipsychotic medication or, if previously treated, a total life-time of antipsychotic treatment of ≤6 weeks; and (5) met the DSM-IV criteria for brief psychotic disorder, schizophreniform disorder, schizophrenia or not otherwise specified (NOS) psychosis. The diagnoses were confirmed through the use of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I),21 conducted by an experienced psychiatrist within six months from the baseline visit.

A group of 156 healthy volunteers were recruited from the community through advertisements. They had no current or past history of psychiatric, neurological or general medical illnesses, including substance abuse and significant loss of consciousness. The abbreviated version of the Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (CASH)22 was completed by a trained interviewer.

Estimation of CR and definition of subgroups by CRTo estimate CR, proxies indicated by the literature were used7,11,14,23 that include: premorbid IQ, education and occupation.

In this work, premorbid IQ was obtained using the WAIS-III vocabulary subtest,24 as was similarly done in previous research.7,14,17,25–30 The use of vocabulary as a proxy measure for premorbid intelligence is based on it being a measure of crystallized intelligence. It is associated with the knowledge base of the subjects, entailing lexical, phonological and semantic information of their dominant language. It has been used to generate an estimate of premorbid IQ in FEP patients and an estimate of IQ in controls.14 The WAIS Vocabulary subtest was validated and normed for most nations, enabling cross-cultural comparisons. Previous research that studied how to measure premorbid IQ in patients with schizophrenia, has shown that the vocabulary test, as a measure of premorbid IQ, is consistent if administered in the subject's dominant language,31 bringing greater reliability than the scores produced by the NART test.32

Education was collected through the educational years of the participants. Occupation was obtained through information on the employment situation of the participants.

The participants, both cases and controls, were assigned to groups according to the result of the estimation of the CR; based on previous literature that uses the mean of the participants as a cut-off point to divide the participants into high or low CR groups.9,25,27,28 The summation of proxies was divided by 3. Considering the arithmetic mean (score 7), two groups were formed: the low CR group with a score less than or equal to 7; the high CR group with a score greater than 7.

Sociodemographic and clinical variablesPremorbid and sociodemographic information was recorded from interviews with patients, their relatives and from medical records at admission. Sex, age, age of psychosis onset (defined as the age when the emergence of the first continuous psychotic symptom occurred), and duration of untreated psychosis (DUP, defined as the time from the first continuous psychotic symptom to initiation of adequate antipsychotic drug treatment) were assessed. Premorbid social adjustment was measured by the Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS).33

Both FEP patients and HC were screened for the following sociodemographic characteristics: sex, age, ethnicity (“Caucasian” vs. “others”), years of education, education level (“only elementary education” vs. “other”), socioeconomic status derived from the parents’ occupation (“low qualification worker” vs. “other”), living area (“urban” vs. “rural”, defined urban as at least 10,000 inhabitants), relationship status (“married/cohabiting” vs. “single/divorced/separate or widowed”), living status (“alone” vs. “other”), employment status (“employed” vs. “unemployed”), and first degree family history of psychosis, which was based on the participants and family reports (“yes” vs. “no”).

Clinical symptoms of psychosis were assessed by means of the Scale for the Assessment of Negative symptoms (SANS)34 and the Scale for the Assessment of Positive symptoms (SAPS).35 The SANS and SAPS scores were used in generating dimensions of positive (scores for hallucinations and delusions), disorganized (scores for formal thought disorder, bizarre behavior and inappropriate affect) and negative (scores for alogia, affective fattening, apathy and anhedonia) symptoms.36 General psychopathology was assessed with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS),37 and depressive symptoms were assessed using the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS).38 Functional assessment was conducted with The Disability Assessment Scale (DAS) Spanish version.39 Antipsychotic treatment, as mean chlorpromazine equivalent dosage was also considered.

Neuropsychological assessmentTrained neuropsychologists carried out the neuropsychological assessments. In order to maximize cooperation, assessments occurred when the patients’ clinical status permitted, which resulted in an average of 10.5 weeks after admission. A detailed description has been reported elsewhere.40 This evaluation included tests of (1) verbal memory (Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, RAVLT)41 to estimate Premorbid IQ, (2) visual memory (Rey Complex Figure, RCF)42 (delayed recall), (3) working memory (WAIS-III, digits forward and backward subtests)24 (standard total score), (4) executive function (Trail Making Test, TMT)43 (trail B-A score), (5) processing speed (WAIS-III, digit symbol subtest)24 (standard total score), (6) motor dexterity (Grooved Pegboard Test)44 (time to complete with dominant hand), and (7) attention (Continuous Performance Test, CPT)45 (correct responses). Raw scores were transformed into Z scores, using a sample of 187 healthy volunteers described in previous studies.29 In order to obtain a measure of global cognitive functioning (GCF), prior to standardization, raw cognitive scores were reversed when appropriate so they were all in the same direction.

Statistical analysisStatistical analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for Social Science version 22.0.46 Comparisons were made between 4 groups: men low CR, men high CR, women low CR and women high CR, independently in FEP patients and in healthy controls. For dichotomous qualitative variables, chi-square tests were performed.

The quantitative sociodemographic, clinical and functional variables, as well as the neurocognitive variables, were subjected to univariate analyses of variance (ANOVA) including the age of onset in the PAFIP program as a covariate.

Paired comparisons were subsequently made and corrected by Bonferroni. All statistics had two tails and significance was set at p<0.05.

ResultsIn patients, 239 participants (54%) have a low CR, being 148 (63%) men and 91 (37%) women; in the control group, 68 participants (44%) had low CR, being 47 (69%) men and 21 (31%) women. On the other hand, in the subgroup with high CR there are 204 FEP patients (46%), of which 98 (48%) are men and 106 (52%) women; the 88 control participants with high CR (56%), 49 (57%) were men and 39 (43%) were women.

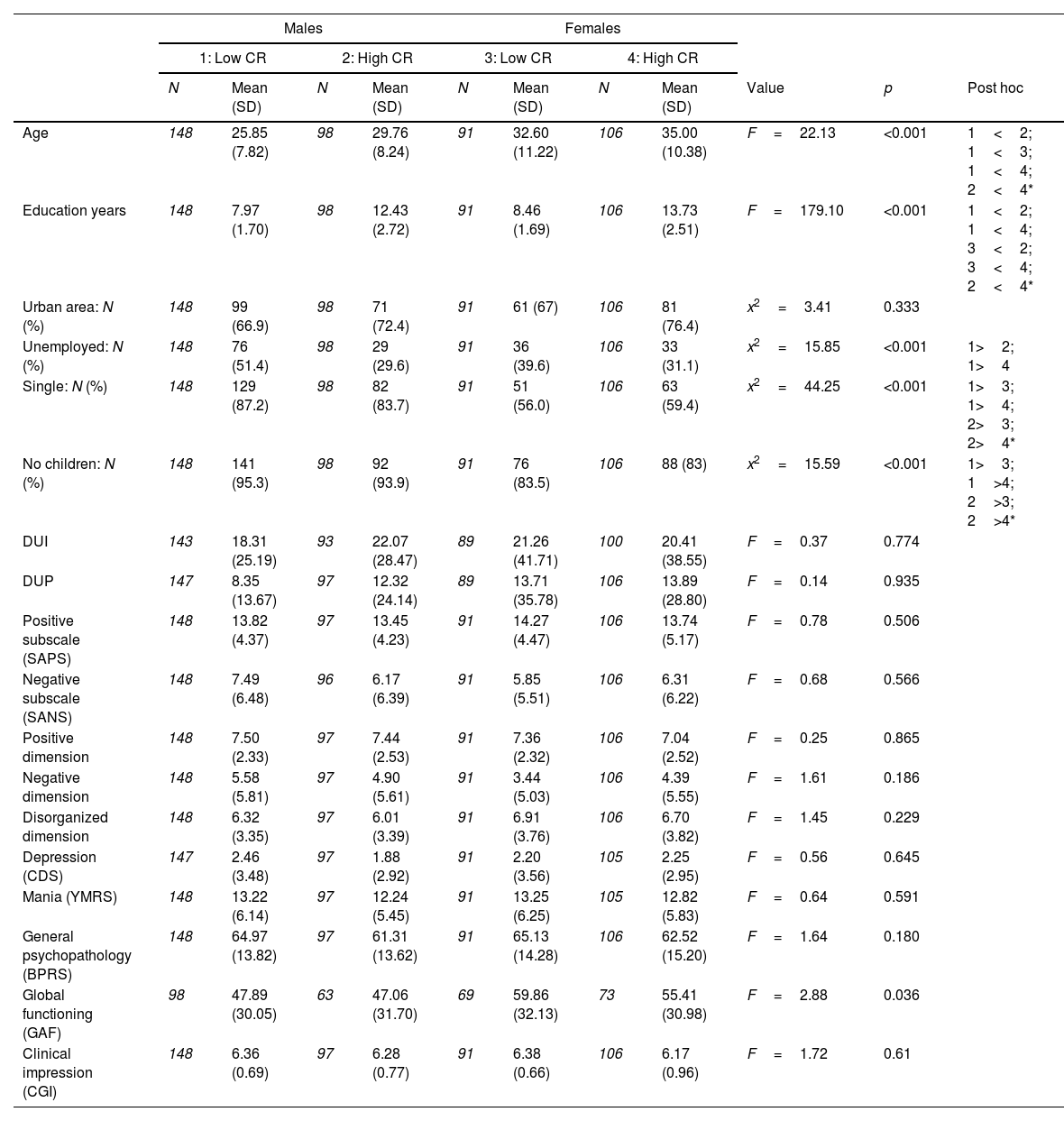

CR subgroup comparisons in FEP patientsTable 1 shows the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample comparing the subgroups of low CR vs. high CR in FEP patients, as well as between sex.

Sociodemographic and clinical comparisons in CR subgroups of FEP patients.

| Males | Females | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Low CR | 2: High CR | 3: Low CR | 4: High CR | ||||||||

| N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | Value | p | Post hoc | |

| Age | 148 | 25.85 (7.82) | 98 | 29.76 (8.24) | 91 | 32.60 (11.22) | 106 | 35.00 (10.38) | F=22.13 | <0.001 | 1<2; 1<3; 1<4; 2<4* |

| Education years | 148 | 7.97 (1.70) | 98 | 12.43 (2.72) | 91 | 8.46 (1.69) | 106 | 13.73 (2.51) | F=179.10 | <0.001 | 1<2; 1<4; 3<2; 3<4; 2<4* |

| Urban area: N (%) | 148 | 99 (66.9) | 98 | 71 (72.4) | 91 | 61 (67) | 106 | 81 (76.4) | x2=3.41 | 0.333 | |

| Unemployed: N (%) | 148 | 76 (51.4) | 98 | 29 (29.6) | 91 | 36 (39.6) | 106 | 33 (31.1) | x2=15.85 | <0.001 | 1>2; 1>4 |

| Single: N (%) | 148 | 129 (87.2) | 98 | 82 (83.7) | 91 | 51 (56.0) | 106 | 63 (59.4) | x2=44.25 | <0.001 | 1>3; 1>4; 2>3; 2>4* |

| No children: N (%) | 148 | 141 (95.3) | 98 | 92 (93.9) | 91 | 76 (83.5) | 106 | 88 (83) | x2=15.59 | <0.001 | 1>3; 1>4; 2>3; 2>4* |

| DUI | 143 | 18.31 (25.19) | 93 | 22.07 (28.47) | 89 | 21.26 (41.71) | 100 | 20.41 (38.55) | F=0.37 | 0.774 | |

| DUP | 147 | 8.35 (13.67) | 97 | 12.32 (24.14) | 89 | 13.71 (35.78) | 106 | 13.89 (28.80) | F=0.14 | 0.935 | |

| Positive subscale (SAPS) | 148 | 13.82 (4.37) | 97 | 13.45 (4.23) | 91 | 14.27 (4.47) | 106 | 13.74 (5.17) | F=0.78 | 0.506 | |

| Negative subscale (SANS) | 148 | 7.49 (6.48) | 96 | 6.17 (6.39) | 91 | 5.85 (5.51) | 106 | 6.31 (6.22) | F=0.68 | 0.566 | |

| Positive dimension | 148 | 7.50 (2.33) | 97 | 7.44 (2.53) | 91 | 7.36 (2.32) | 106 | 7.04 (2.52) | F=0.25 | 0.865 | |

| Negative dimension | 148 | 5.58 (5.81) | 97 | 4.90 (5.61) | 91 | 3.44 (5.03) | 106 | 4.39 (5.55) | F=1.61 | 0.186 | |

| Disorganized dimension | 148 | 6.32 (3.35) | 97 | 6.01 (3.39) | 91 | 6.91 (3.76) | 106 | 6.70 (3.82) | F=1.45 | 0.229 | |

| Depression (CDS) | 147 | 2.46 (3.48) | 97 | 1.88 (2.92) | 91 | 2.20 (3.56) | 105 | 2.25 (2.95) | F=0.56 | 0.645 | |

| Mania (YMRS) | 148 | 13.22 (6.14) | 97 | 12.24 (5.45) | 91 | 13.25 (6.25) | 105 | 12.82 (5.83) | F=0.64 | 0.591 | |

| General psychopathology (BPRS) | 148 | 64.97 (13.82) | 97 | 61.31 (13.62) | 91 | 65.13 (14.28) | 106 | 62.52 (15.20) | F=1.64 | 0.180 | |

| Global functioning (GAF) | 98 | 47.89 (30.05) | 63 | 47.06 (31.70) | 69 | 59.86 (32.13) | 73 | 55.41 (30.98) | F=2.88 | 0.036 | |

| Clinical impression (CGI) | 148 | 6.36 (0.69) | 97 | 6.28 (0.77) | 91 | 6.38 (0.66) | 106 | 6.17 (0.96) | F=1.72 | 0.61 | |

The group of FEP patients with low CR was made up of more men than women, contrary to what occurs in the high CR group where women predominate versus men.

Regarding the age of onset of psychosis, FEP men with low CR debut significantly earlier, with a mean age of 25.85 years, compared to the rest of the subgroups. Furthermore, these men with low CR are more frequently unemployed than the group with high CR, both men and women. We also found a significant difference in the high CR subgroup where men debut younger than women.

On the other hand, in the high CR group, both men and women have more years of education than the low CR group. While within this high CR group, men have fewer years of education than women.

Another significant difference is found in the single and childless variables. Men show a tendency to be more frequently single and not having children compared to women.

Finally, no significant differences were found between the groups in clinical variables.

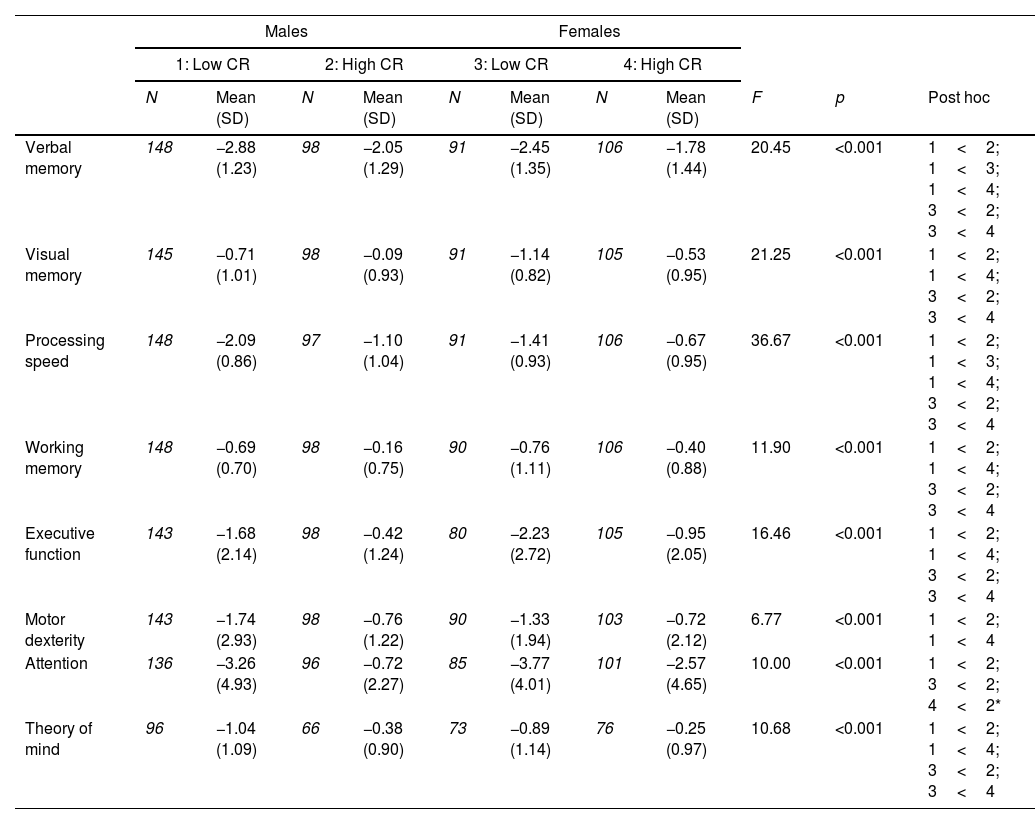

Neuropsychological resultsAmong FEP patients there are numerous significant differences in cognitive domains, as can be seen in Table 2.

Comparisons of cognitive domains in CR subgroups of FEP patients.

| Males | Females | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Low CR | 2: High CR | 3: Low CR | 4: High CR | ||||||||

| N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | F | p | Post hoc | |

| Verbal memory | 148 | −2.88 (1.23) | 98 | −2.05 (1.29) | 91 | −2.45 (1.35) | 106 | −1.78 (1.44) | 20.45 | <0.001 | 1<2; 1<3; 1<4; 3<2; 3<4 |

| Visual memory | 145 | −0.71 (1.01) | 98 | −0.09 (0.93) | 91 | −1.14 (0.82) | 105 | −0.53 (0.95) | 21.25 | <0.001 | 1<2; 1<4; 3<2; 3<4 |

| Processing speed | 148 | −2.09 (0.86) | 97 | −1.10 (1.04) | 91 | −1.41 (0.93) | 106 | −0.67 (0.95) | 36.67 | <0.001 | 1<2; 1<3; 1<4; 3<2; 3<4 |

| Working memory | 148 | −0.69 (0.70) | 98 | −0.16 (0.75) | 90 | −0.76 (1.11) | 106 | −0.40 (0.88) | 11.90 | <0.001 | 1<2; 1<4; 3<2; 3<4 |

| Executive function | 143 | −1.68 (2.14) | 98 | −0.42 (1.24) | 80 | −2.23 (2.72) | 105 | −0.95 (2.05) | 16.46 | <0.001 | 1<2; 1<4; 3<2; 3<4 |

| Motor dexterity | 143 | −1.74 (2.93) | 98 | −0.76 (1.22) | 90 | −1.33 (1.94) | 103 | −0.72 (2.12) | 6.77 | <0.001 | 1<2; 1<4 |

| Attention | 136 | −3.26 (4.93) | 96 | −0.72 (2.27) | 85 | −3.77 (4.01) | 101 | −2.57 (4.65) | 10.00 | <0.001 | 1<2; 3<2; 4<2* |

| Theory of mind | 96 | −1.04 (1.09) | 66 | −0.38 (0.90) | 73 | −0.89 (1.14) | 76 | −0.25 (0.97) | 10.68 | <0.001 | 1<2; 1<4; 3<2; 3<4 |

Significant results were shown with the same direction in the cognitive domains of verbal memory and processing speed: the high CR group outperforms the low CR group. In both cognitive domains, men with low CR score significantly lower than men with high CR and then women with low and high CR. In turn, both high CR men and women significantly outperform low CR women in the domains of verbal memory and processing speed.

A secondary analysis, in the form of a regression model, was conducted in order to test the hypothesis of verbal memory domain as a predictor of CR in FEP women. This model was statistically significant (X2(1)=10.994, p≤0.001)) and accounted for 7.3% of the variance (Nagelkerke R2=0.073). Verbal memory predicted CR with 60.9% accuracy, correctly classifying 45.1% of FEP women with low CR and 74.5% of FEP women with high CR.

In the visual memory, working memory, executive functions and theory of mind domains, the high CR group shows significantly better performance compared to the low CR group. Low CR women present worse results than high CR women and men in these domains. The high CR group also outperforms the low CR men in these domains. The same effect is observed in the motor skill domain, the high CR group has better performance than men with low.

The cognitive domain of attention shows significant differences between the men with high CR and low CR group. Men with high CR perform better in attention domain than men and women with low CR. In turn, men with high CR obtained better results in the attention domain than women with high CR.

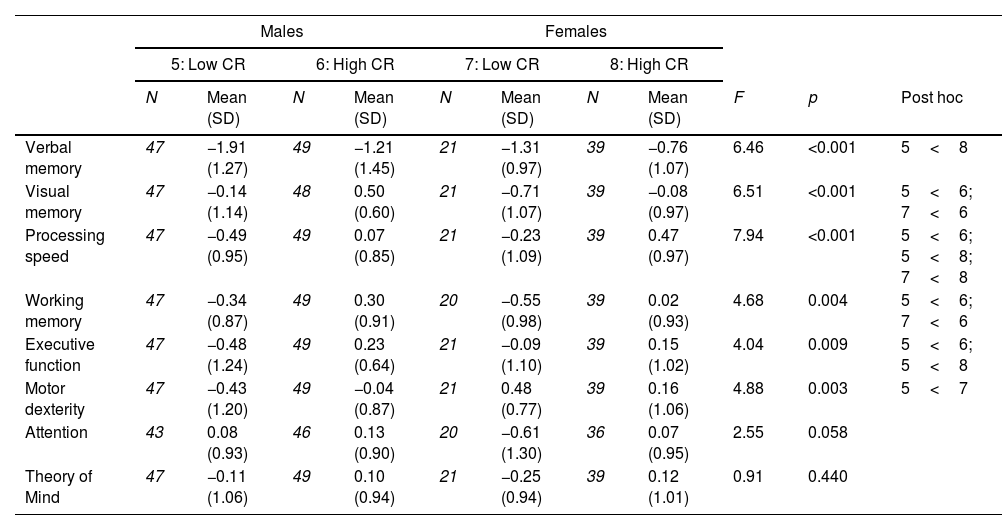

Neuropsychological comparisons between CR subgroups in control groupCognitive performance differences are found in the control group, as seen in Table 3.

Comparisons of cognitive domains in control group.*

| Males | Females | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5: Low CR | 6: High CR | 7: Low CR | 8: High CR | ||||||||

| N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | F | p | Post hoc | |

| Verbal memory | 47 | −1.91 (1.27) | 49 | −1.21 (1.45) | 21 | −1.31 (0.97) | 39 | −0.76 (1.07) | 6.46 | <0.001 | 5<8 |

| Visual memory | 47 | −0.14 (1.14) | 48 | 0.50 (0.60) | 21 | −0.71 (1.07) | 39 | −0.08 (0.97) | 6.51 | <0.001 | 5<6; 7<6 |

| Processing speed | 47 | −0.49 (0.95) | 49 | 0.07 (0.85) | 21 | −0.23 (1.09) | 39 | 0.47 (0.97) | 7.94 | <0.001 | 5<6; 5<8; 7<8 |

| Working memory | 47 | −0.34 (0.87) | 49 | 0.30 (0.91) | 20 | −0.55 (0.98) | 39 | 0.02 (0.93) | 4.68 | 0.004 | 5<6; 7<6 |

| Executive function | 47 | −0.48 (1.24) | 49 | 0.23 (0.64) | 21 | −0.09 (1.10) | 39 | 0.15 (1.02) | 4.04 | 0.009 | 5<6; 5<8 |

| Motor dexterity | 47 | −0.43 (1.20) | 49 | −0.04 (0.87) | 21 | 0.48 (0.77) | 39 | 0.16 (1.06) | 4.88 | 0.003 | 5<7 |

| Attention | 43 | 0.08 (0.93) | 46 | 0.13 (0.90) | 20 | −0.61 (1.30) | 36 | 0.07 (0.95) | 2.55 | 0.058 | |

| Theory of Mind | 47 | −0.11 (1.06) | 49 | 0.10 (0.94) | 21 | −0.25 (0.94) | 39 | 0.12 (1.01) | 0.91 | 0.440 | |

In the verbal memory domain, women with high CR had significantly higher performance than men with low CR. While in the motor dexterity domain, women with low CR were those with significantly higher scores than men with low CR. The domains visual memory and working memory had the same relationship. Men with high CR show better performance than men and women with low CR. Finally, the processing speed domain presents significantly lower scores in the low CR group. Men with low CR had a lower performance in this cognitive domain than the group with high CR, while women with low CR had a lower performance only than women with high CR. This same direction occurs in the executive function's domain, men with low CR perform significantly less than the group with high CR.

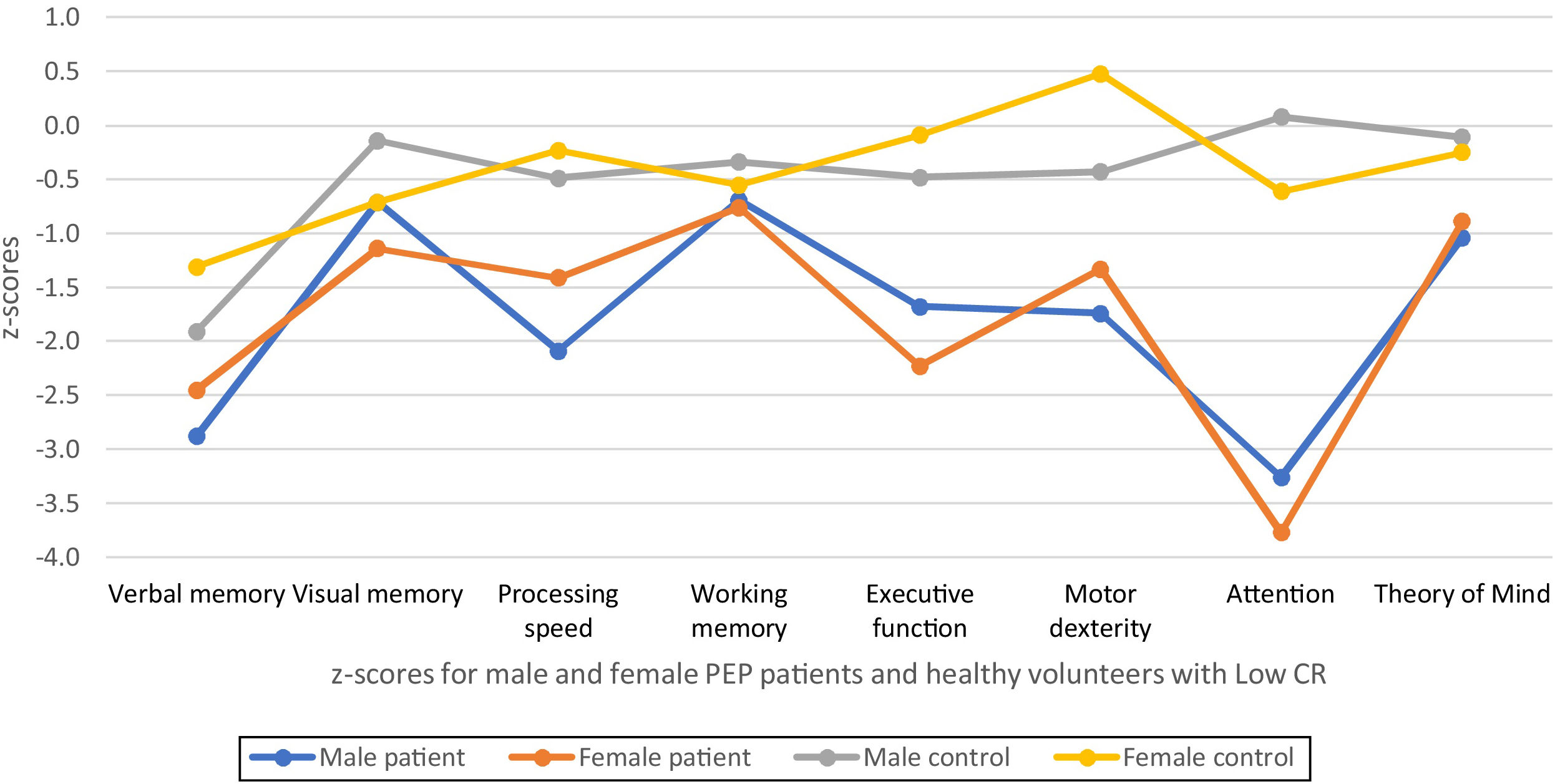

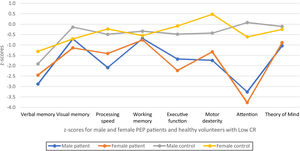

Comparisons between groups and sexes in neuropsychological testsMaking comparisons between sexes within the low CR group in both groups, we can see variations in the cognitive domains as seen in Fig. 1. Significant differences appear in the domains of verbal memory and processing speed with FEP women presenting higher performance than FEP men. While motor dexterity presents significant differences in the control group, women also had higher performance than men. As can be seen in Fig. 1, in FEP patients we found serious alterations in the domains of attention and verbal memory, as well as executive functions in women and processing speed in men. It was striking to observe that the low CR controls present alterations in verbal memory.

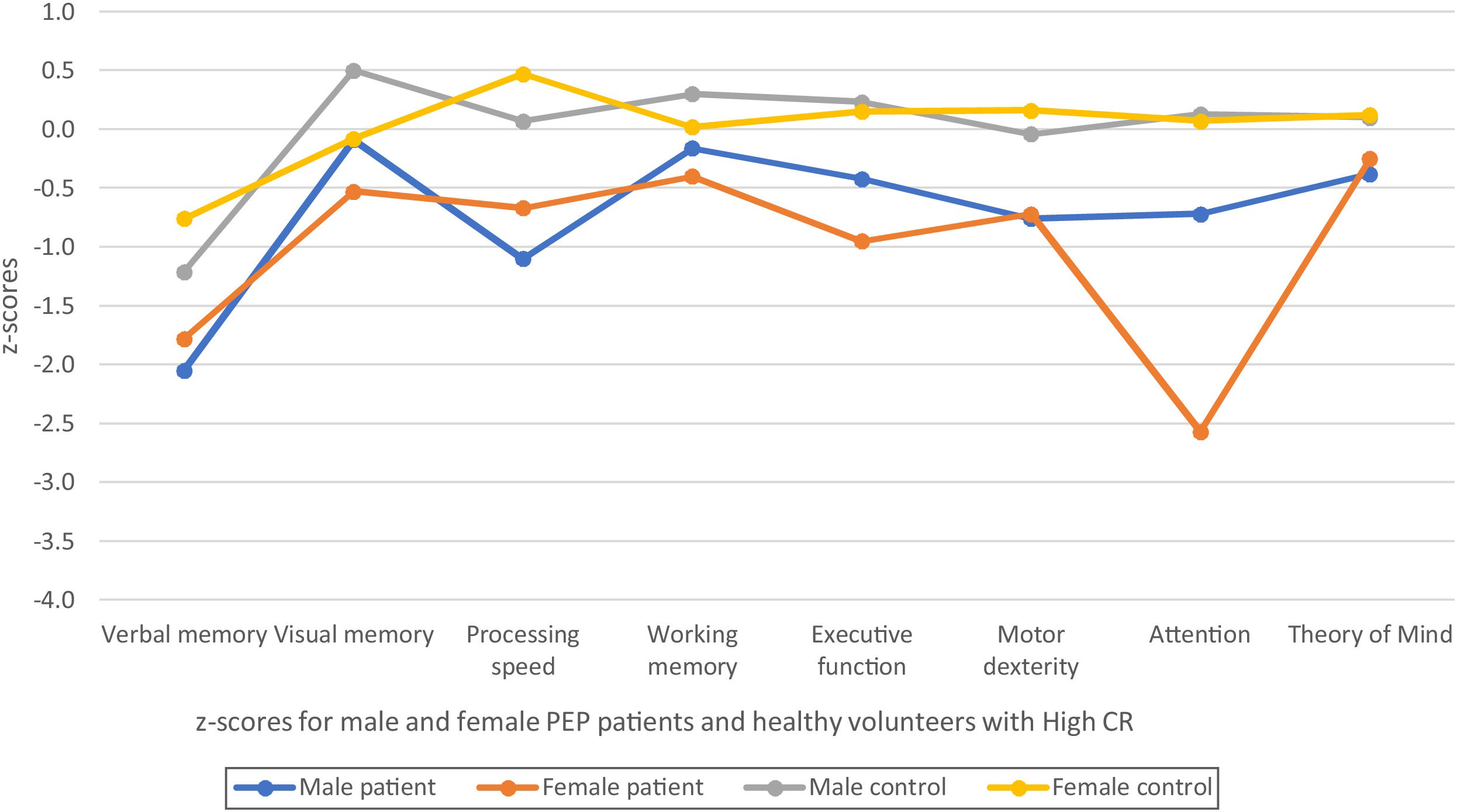

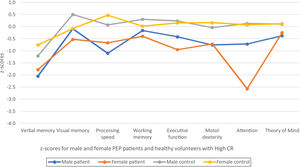

On the other hand, comparisons between the high CR group only show significant differences between FEP patients, as shown in Fig. 2. Men show better performance than women in the domain of attention, the severe alteration being very striking presented by FEP women with high CR in this domain. Also, in this group, the result obtained in the verbal memory domain was striking, being moderate-severe alteration in the FEP group and mild alteration in controls. It was very curious that the women with high CR controls did not obtain positive scores in the verbal memory domain.

DiscussionThe present study confirmed that FEP women had higher CR, showing even those with low CR better performed in the domains verbal memory and processing speed. This could be explained attending specific differences observed between FEP men and women at illness onset.

Consistent with the literature, FEP men showed an earlier onset of the disorder5,47 and higher unemployment rates,12,14 especially those who had low CR.9,14,17 This result could indicate that people with high CR better tolerate the effects of psychosis, as occurs with Alzheimer's disease.13 In addition, the results coincide with the theory of Barnett and colleagues which reported that the onset of the disorder was delayed in a patient with high CR: the lower the CR, the greater the vulnerability to develop the disorder,5 responding to a greater capacity reasoning out strange perception.2 In this work, we can say that the theory proposed by Barnett and colleagues was confirmed, given the circumstance that FEP women had higher CR, which in turn could influence that the later onset of the disease than in FEP men.5 Another way to explain this late onset in women would be that by having higher CR they have been able to count on alternative and therefore more flexible neural networks that have allowed them to enhance their abilities and compensate for limitations.14,48 It was also observed that men were single and childless more frequently than women,9 variables that act as protective factors and good prognosis in mental disorder.

In addition, coinciding with previous studies, the high CR group had completed more years of education.9 Specifically, coinciding with previous research, the results of this study showed that women had a higher average number of years of education.1,11,23,47,49 This result was reflected when it came to seeing which sex had the highest CR, since years of education was a variable added as a proxy to the CR estimate.9 Therefore, the strong association between the participant's education, their CR and the age of onset of the disorder was appreciated. If the women in our study are the ones with the most educational years, it makes sense that they are the ones who later develop the disorder because they have a greater capacity to use alternative neural networks to compensate for deficits1 and because cognitive processes mediate the way of perceiving strange experiences causing subjects with high cognitive ability to delay the onset of the disorder.5 It is possible that since years of education are one of the proxies used to estimate CR, presenting more educational years and therefore higher CR, it can be considered a protective factor for the development of psychosis. According to previous research that found that the more years of education in FEP patients, the higher the premorbid IQ and the higher the performance in the cognitive domains.47 In addition, the literature indicates that 10 years later, those FEP patients with high and medium education presented global functioning similar to the control group and performance in the cognitive domains within normal limits.47 This fact reaffirms the need to include educational achievements in psychosis preventive programs.

It is interesting that the present work did not show significant differences between the CR groups of FEP patients with respect to the severity of the symptoms. This follows the line of previous studies that did not show differences between premorbid IQ and clinical symptoms.16 On the other hand, previous studies relate having a high CR with a better prognosis of the disease, stating that at 2 years of follow-up, patients with fewer psychotic symptoms had better premorbid adjustment, less severity of the disease, greater functioning and more intellectual-cultural orientation.50

In reference to the association between CR and cognitive domains, coinciding with the previous literature, it was observed that CR and the age of onset of the disorder predict cognitive decline.51 Thus, a FEP patient with an early onset of the disorder will have low CR and greater impairment in cognitive domains.

The present study shows that in the domains of verbal memory and processing speed, the high CR group shows better scores than the low CR group. Coinciding with previous works, the present study finds a relationship between CR and the verbal memory domain.8,17,25,30 In addition, it has been proven that a better verbal memory could be a predictor of high CR in FEP women. However, these results disagree with studies that show no association with the verbal memory domain in the evaluation at 10 years.17 The present study shows that in the domains of verbal memory and processing speed, the high CR group shows better scores than the low CR group. In addition, within the low CR group, we see that women perform better in these domains than men. On the one hand, these results coincide with the literature in that they show us that lower cognitive functioning indicates a greater deterioration in processing speed.14 But on the other hand, previous research showed that FEP women with high cognitive functioning presented better performance in the verbal memory domain than men with both high and low cognitive functioning12 and not only with the men with low CR as indicated by the results of this work.

Regarding performance in the visual memory, working memory, executive functions and theory of mind domains, our results in patients showed that the high CR group showed better performance than the low CR group. These results are consistent with previous research which indicated that the lower the cognitive functioning, the greater the overall cognitive deterioration, especially in the executive functions domain.14 This was consistent with previous studies on CR were associated with the working memory domain.7–10

The executive functions domain shows discrepancies throughout the literature. Although the association between CR and the executive functions domain was strong both in this work and in previous research,7–10 there are differences as to which executive function specifically, it was part of the association. On the one hand, a greater association with the planning domain26,52 and on the other hand, no association with the flexibility domain,11 therefore we suggest that this aspect should be further studied. Regarding the differences according to sex, as previously mentioned, both men and women with high CR have better performance than both sexes in the low CR group on the domains of visual memory, working memory, executive functions and ToM. The present study did not find significant differences in the same sex with different CR, while previous research showed that FEP men had higher performance than FEP women on the domains of visual memory, executive functions and reaction time.12

The results in the domain ToM showed that the higher the CR, the higher the ToM in FEP patients, as shown in other studies.52 Some previous literature showed that it was social cognition and not CR that predicted the patient's functionality and that was associated with the processing speed and verbal memory domains, and it was not clear whether it was the premorbid functioning of social cognition that influences the evolution of the disease10 or if, on the contrary, it was CR that influences the social cognition and functioning of the patient as occurs in this work and previous studies.52 Following this question, research on interpersonal thinking informs us that those patients with a high level of dichotomous interpersonal thinking had a lower CR than patients with flexible interpersonal thinking, in addition to a deterioration in the executive functions domain, supporting the theory that low interpersonal thinking influences an earlier onset of the disorder and a low estimate of CR.53

There is incongruity regarding the results of the literature regarding in attention domain since in certain studies of premorbid IQ they found no relationship with this domain, but research on CR did find an association with the attention domain.8,17 Perhaps in previous research the difference was since only the association with premorbid IQ or with CR was studied where more variables come into play for its estimation. Our results showed that in FEP patients, men with high CR performed better than both sexes with low CR. Even our data showed differences in FEP patients within the high CR group in the care domain, with men being better than women.

LimitationsThe main limitation was to estimate the CR and specifically calculate the premorbid IQ, which was measured using the WAIS-III vocabulary test, which, although it has been previously tested to measure crystallized intelligence,14 intelligence could have been impaired in the premorbid period. Another limitation was not having considered the socioeconomic variable collected according to the occupation of the parents of the participants. It may be a limitation because previous research has shown that the socioeconomic variable shows differences where FEP patients with low cognitive functioning show lower socioeconomic levels than those with high cognitive functioning.7,14,25,47 The last limitation to mention was not having considered other CR proxies proposed in other investigations7,11,23 such as leisure activities, physical activity or the educational level of parents who can influence CR.

ConclusionsIn general FEP women presented higher CR than FEP men. However, the variability in performance observed on verbal memory, processing speed and attention domains is closely linked to sex differences in CR. This information could be relevant to design sex specific cognitive remediation interventions in FEP patients.

Role of fundingThis work was supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI14/00639 and PI14/00918). Dr. Ayesa-Arriola is funded by a Miguel Servet contract from the Carlos III Health Institute (CP18/00003), carried out on Fundación Instituto de Investigación Marqués de Valdecilla. No pharmaceutical company has financially supported the study.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

The authors wish to thank the PAFIP research team and all patients and family members who participated in the study.