Opportunistic infections are an increasingly common problem in hospitals, and the yeast Candida parapsilosis has emerged as an important nosocomial pathogen, especially in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) where it has been responsible for outbreak cases. Risk factors for C. parapsilosis infection in neonates include prematurity, very low birth weight, prolonged hospitalization, indwelling central venous catheters, hyperalimentation, intravenous fatty emulsions and broad spectrum antibiotic therapy. Molecular methods are widely used to elucidate these hospital outbreaks, establishing genetic variations among strains of yeast.

AimsThe aim of this study was to detect an outbreak of C. parapsilosis in an NICU at the “Hospital das Clinicas”, Faculty of Medicine of Botucatu, a tertiary hospital located in São Paulo, Brazil, using the molecular genotyping by the microsatellite markers analysis.

MethodsA total of 11 cases of fungemia caused by C. parapsilosis were identified during a period of 43 days in the NICU. To confirm the outbreak all strains were molecularly typed using the technique of microsatellites.

ResultsOut of the 11 yeast samples studied, nine showed the same genotypic profile using the technique of microsatellites.

ConclusionsOur study shows that the technique of microsatellites can be useful for these purposes. In conclusion, we detected the presence of an outbreak of C. parapsilosis in the NICU of the hospital analyzed, emphasizing the importance of using molecular tools, for the early detection of hospital outbreaks, and for the introduction of effective preventive measures, especially in NICUs.

Las infecciones oportunistas son un problema cada vez más frecuente en los hospitales, y Candida parapsilosis se está convirtiendo en un importante patógeno nosocomial, sobre todo en las unidades de cuidados intensivos neonatales (UCIN) donde ha sido responsable de brotes de candidiasis invasoras. En recién nacidos, los factores de riesgo de infección por C. parapsilosis incluyen la prematuridad, bajo peso al nacer, la hospitalización prolongada, los catéteres venosos centrales permanentes, alimentación parenteral, las emulsiones grasas por vía intravenosa y la administración de antibióticos de amplio espectro. Para esclarecer el origen y evolución de estos brotes hospitalarios, pueden utilizarse métodos moleculares, que permiten estudiar las variaciones genéticas entre los aislamientos clínicos.

ObjetivosEl objetivo del presente estudio fue estudiar un brote de C. parapsilosis en la UCIN del Hospital das Clinicas, Facultad de Medicina de Botucatu, un hospital de asistencia terciaria de São Paulo, Brasil, usando una técnica de genotipificación molecular basada en el estudio de microsatélites.

MétodosDurante un período de 43 días en la UCIN, se diagnosticaron un total de 11 casos de fungemia por C. parapsilosis. Para confirmar el brote, todas las cepas se sometieron a análisis de tipificación molecular utilizando la técnica de microsatélites.

ResultadosSe observó el mismo genotipo en 9 de las 11 cepas estudiadas, lo que permitió confirmar la presencia de un brote de C. parapsilosis en la UCIN del hospital.

ConclusionesEl presente estudio revela que el análisis de marcadores de microsatélites puede ser de utilidad para los objetivos ya mencionados. Es de destacar la importancia de usar técnicas moleculares para la detección precoz de brotes hospitalarios y la introducción eficaz de medidas preventivas, en especial en las UCIN.

Until the 1970s, systemic yeast infections were considered rare, and fungi were not among the most isolated etiologic agents in hospitals. From that time on, there was a significant increase in the incidence and frequency of nosocomial mycoses.17Candida species are responsible for up to 78% of the cases of nosocomial fungal infections, and represent the major cause of bloodstream infections.21

Although Candida albicans remains as the most isolated yeast in bloodstream infections, there has been in recent years an increase in the number of candidemia cases casues by other Candida species.6 Some studies have reported that the latter candidemia cases are around 40-50%.18,19,24Candida parapsilosis is one of the most frequent species causing bloodstream infections in hospitalized patients, accounting for 10–25% of the episodes of candidemia in the world, particularly in neonates,1,23,30 where this species is responsible for 17–50% of cases when compared with adult patients admitted to ICU (2.5–12%).14 It is the second most isolated yeast species from bloodstream infections in outbreaks in neonatal ICUs.23

Unlike other Candida species, C. parapsilosis causes nosocomial candidemia without prior colonization of other sites, suggesting that this yeast can gain access to the bloodstream directly from exogenous locations.13 Infections are associated with the use of central venous catheters, the use of parenteral nutrition and the transmission by the hands of the health professionals.21 However, the epidemiology of nosocomial C. parapsilosis is not completely defined and may involve other sources such as endogenous microbiota and the hospital environment itself.15 All these factors may occasionally be related to outbreaks.2,5

The molecular methods are widely used in epidemiological investigations, clarifying hospital outbreaks.20 Several molecular typing methods have been used to differentiate yeast isolates, since there is no “gold standard”. Among these, RFLP (Restriction Fragment Length’ Polymorphisms), analysis of randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD), the karyotyping by PFGE (pulsed-field gel Electrophoresis) and, more recently, the technique of microsatellites, a tool with high discriminatory power are included.31

The short tandems repetition (STRs) or microsatellites have assumed an important role as molecular markers of eukaryotic genomes in several areas, such as oncogenetic, population genetics and the characterization, identification and typing of isolates, including C. parapsilosis25,31 as well as the elucidation of outbreaks, by this species in NICUs.10,29

Therefore, the objectives of this paper were to confirm an outbreak of C. parapsilosis in NICU patients, using the technique of microsatellites.

Materials and methodsPatientsA total of 11 cases of fungemia by C. parapsilosis (from 11 patients) were identified during a period of 43 days in the NICU at the “Hospital das Clínicas”, Faculty of Medicine of Botucatu, a tertiary hospital with about 467 beds, located in the State of São Paulo, Brazil. The neonatal patients with ages ranging from 7 to 60 days, with 8 males and 3 females, were considered for the study. To check for a possible outbreak in this unit, molecular investigations were initiated. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethical Committee of the University of São Paulo and in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975.

Identification of yeastsAll the clinical isolates (n=11) of C. parapsilosis were studied as to their macroscopic, microscopic, reproductive and physiological characteristics, in accordance with the methods recommended by Kurtzman and Fell11, and by their sugars’ assimilation profiles using the ID32C commercial kit (bioMérieux Vitek, Inc., Hazelwood, MO) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The strains are maintained in the fungal collection of the Laboratory of Yeast ICBII the USP-São Paulo and in the Mycology Laboratory of the IB-UNESP Botucatu, SP.

DNA extraction and microsatellite analysisThe extraction of the genomic DNA samples was performed according to the method described by Scherer and Steven.27 All isolates of C. parapsilosis were molecularly typed through the technique of microsatellites, whereas the repetitive nucleotide sequences of these microsatellites and the primers used for the PCR reaction were based on prior publication of Lasker et al.12 Therefore, the microsatellite locus A and B were analyzed. Each PCR primer pair was synthesized and the anti-sense primer of each pair was fluorescently labeled by FAM. For the amplification of the locus of C. parapsilosis, the PCR was performed separately in 25μl reactions containing Mg+1× buffer (Biotools, Brazil), 0.2μM of each primer (Invitrogen, Brazil), 0.2μM of dNTP (Biotools, Brazil), 2.5U of Taq polymerase (Biotools, Brazil) and 1μl of DNA extracted from each sample. The parameters for amplification were: denaturation at 95°C for 3min, 30 cycles for denaturation for 30s at 95°C, annealing at 58°C for 30s and extension at 72°C for 1min, and a final extension at 72°C for 5min. The amplification reactions were carried out using a thermal cycler (MJ Research PTC-100). The PCR product was analyzed in an automated sequencer device MegaBACE 1000 (GE-Amersham Biosciences) by capillary electrophoresis system, using the software Genetic Profiler and with the use of MegaBACE ET-550R as a standard marker, with fragments ranging from 60 to 550bp. The differentiation among the isolates was reached by comparing the length of base pairs obtained from the PCR product of each isolate, according to Botterel et al.3 To ensure reproducibility of the method, the strain ATCC 22019 of C. parapsilosis was used.

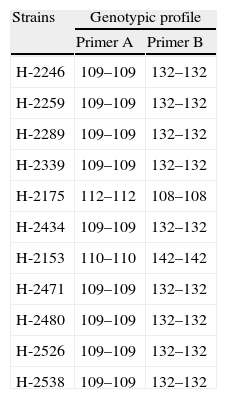

ResultsAs noted in Table 1, with the exception of two samples, all the others showed the same microsatellite genotype. The genotypic profile for the nine isolates was 109–109bp and 132–132bp, for the primers used in the study. These results suggest that the isolates from the nine patients were derived from the same strain.

The length of base pairs for the microsatellite analysis of 11 isolates of C. parapsilosis from the NICU of the “Hospital das Clinicas”, Faculty of Medicine of Botucatu, São Paulo, Brazil, using the primers A and B.

| Strains | Genotypic profile | |

| Primer A | Primer B | |

| H-2246 | 109–109 | 132–132 |

| H-2259 | 109–109 | 132–132 |

| H-2289 | 109–109 | 132–132 |

| H-2339 | 109–109 | 132–132 |

| H-2175 | 112–112 | 108–108 |

| H-2434 | 109–109 | 132–132 |

| H-2153 | 110–110 | 142–142 |

| H-2471 | 109–109 | 132–132 |

| H-2480 | 109–109 | 132–132 |

| H-2526 | 109–109 | 132–132 |

| H-2538 | 109–109 | 132–132 |

Multiple risk factors for acquisition of fungemia by C. parapsilosis in neonatal intensive care units have been identified. These include prematurity, low birth weight, prolonged hospitalization, use of central venous catheters, hyperalimentation, the use of intralipid, parenteral nutrition and the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, particularly third-generation cephalosporins.16

In our study we demonstrated with the help of molecular biology the presence of an outbreak of C. parapsilosis in the NICU. The data presented in this study show that from the 11 samples of C. parapsilosis isolates in the NICU, nine had the same genotypic profile, i.e. a single strain was the causative agent of nine cases of fungemia in a short period of time, in different patients and in the same unit hospital. Previous studies have shown that C. parapsilosis is a common cause of “clusters” and a common source of outbreaks in neonatal intensive care units.4,7,8,26

The molecular analysis of phenotypically identical isolates is crucial to establish the presence of an outbreak. Several methods based on genotypic markers have been employed to investigate the presence of hospital outbreaks, such as RAPD and RFLP.29

In our study for the detection of the outbreak, we used the technique of microsatellites, which has been widely used as an epidemiological marker.9 The microsatellites are considered stable markers, easy to analyze, and adaptable to large-scale series with high discriminatory power. They are used as a typing system to investigate clinical problems such as nosocomial transmission of C. parapsilosis.12,31

Once the outbreak is confirmed the presence of a common element must be established, so that with its removal the epidemiological chain is interrupted. The sources of the outbreaks can be the use of parenteral nutrition, the use of catheters, or more often the contaminated hands of the medical staff.28 The transmission from one patient to another can occur in short periods, under a month; however, Candida isolates may remain for a prolonged time (10 months) in the unit.22

In cases of outbreaks of C. parapsilosis, it is not always viable to identify the possible source and route of transmission of the infection, taking into account that the epidemiology of this yeast infection is not fully known.29 In our study the source of infection was not revealed, since we only studied the yeast samples isolated from blood of patients, and the environment and other fomites were not investigated. We note that the patient whose isolated sample was identified as H-2153 was the first to acquire fungemia by C. parapsilosis.

Outbreaks, as reported in this study, show the importance of C. parapsilosis as a pathogen often found causing fungemia in neonatal ICUs, which is related to high mortality. We also emphasize that the use of molecular methods has been shown to be relevant in cases of outbreaks, as it makes it possible to distinguish specific isolates within a given organism, important in terms of rapid and effective detection of hospital outbreaks for the adoption of rational preventive measures, especially in hospitals at higher risk such as neonatal ICUs. Our study shows that the technique of microsatellites can be very useful for these purposes.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

The authors express their thanks to PhD Marina Korte for her revision of the English text, and to São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) for their financial support.