Malassezia pachydermatis is a yeast of importance in both veterinary and human medicine.

AimsTo know if M. pachydermatis grow on micological media with high concentrations of gentamycin.

MethodsTwenty M. pachydermatis strains were streaked on Sabouraud Dextrose Agar plates with different concentrations of gentamycin.

ResultsAll isolates were inhibited when high concentrations of gentamycin were added.

ConclusionsThe use of plates with high concentrations of gentamycin can lead to some important misdiagnoses: firstly, false-negative cultures, and secondly, an erroneous classification of M. pachydermatis as a lipid-dependent species. Morever, all of this could be useful in two therapeutic fields: i) in animals, topical gentamycin could be an efficacious treatment for a disease such as external otitis in dogs; ii) in humans, we hypothesize that gentamycin could be regarded as a possible therapy (“antibiotic-lock”) for catheter-associated Malassezia spp. infections.

Malassezia pachydermatis es una levadura de gran interés tanto en medicina humana como en veterinaria.

ObjetivosConocer si la adición de gentamicina a los medios micologicos más comunes era capaz de inhibir el crecimiento de M. pachydermatis.

MétodosSe estudiaron 20 cepas de M. pachydermatis en medios micológicos con gentamicina a diferentes concentraciones.

ResultadosTodos los aislamientos se inhibieron con altas concentraciones de gentamicina.

ConclusionesEl uso de placas con altas concentraciones de gentamicina puede llevar a resultados falsamente negativos en cultivo y a una errónea clasificación de M. pachydermatis como especie lípido-dependiente. Estas observaciones podrían llegar a tener dos aplicaciones hipotéticas: i) en veterinaria, la gentamicina tópica podría ser eficaz en procesos como la dermatitis o la otitis externa, y ii) en humanos, podría ser una terapia (“antibiotic-lock”) para las infecciones por Malassezia relacionadas con el uso de catéteres.

Malassezia pachydermatis is a lipophilic yeast of importance in both veterinary and human medicine.7M. pachydermatis has been rarely associated with systemic infections of humans, although fungemia has been reported in patients receiving parenteral nutrition.4,2 However, infections associated with M. pachydermatis in animals are frequent and include mainly dermatitis and otitis in dogs.7

Canine external otitis (OE) is a disease of multifactorial aetiology, and the microorganism most frequently isolated is M. pachydermatis, often in combination with Staphylococcus intermedius bacteria.8 Additionally, Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the organism most frequently isolated from dogs with suppurative EO.8 External otitis related to M. pachydermatis is usually secondary to underlying problems.7 Although the evidence for a pathogenic role for the yeast remains circumstantial, the best therapeutic response is achieved when both M. pachydermatis and bacteria are removed by topical therapy.7 Concerning bacteria, both S. intermedius and P. aeruginosa show good susceptibility to gentamycin.8

In order to examine the ear exudate in dogs with ceruminous or exudative EO, rolling of exudate in a thin layer on glass slides with a cotton-tipped swab may be the preferred method.9 However, culture may be useful to study the yeast, either on normal skin and mucosae or on the otitis or dermatitis skin. Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) with a 27–35°C incubation temperature allows the isolation of most fungal species responsible for cutaneous diseases in mammals (Microsporum canis and other dermatophytes, M. pachydermatis and Candida spp.) However, specific media with lipid supplements, such as Leeming and Notman medium or modified Dixon's medium6, may be appropriate to isolate all Malassezia species. Some key characteristics of the different species of Malassezia to routinely facilitate their identification have been reported. These characteristics include growth on SDA, tolerance to high temperatures, catalase activity and growth in Tween as the sole lipid supplement in a regular medium.5 The first step in this identification scheme of Malassezia yeasts is making a new culture on SDA (at 32°C). If growth on SDA is observed, the organism is the non-lipid-dependent strains of M. pachydermatis.5

During a survey of the appearance of strains of M. pachydermatis, we observed a systematic absence of growth on several media, mainly on commercialized Sabouraud medium (Sabouraud Gentamycin chloramphenicol, BioMérieux, Marcy l’Étoile, France).1 To assess in detail these culture characteristics and the probable existence of an inhibitor substance in the composition of some of these media we performed this study.

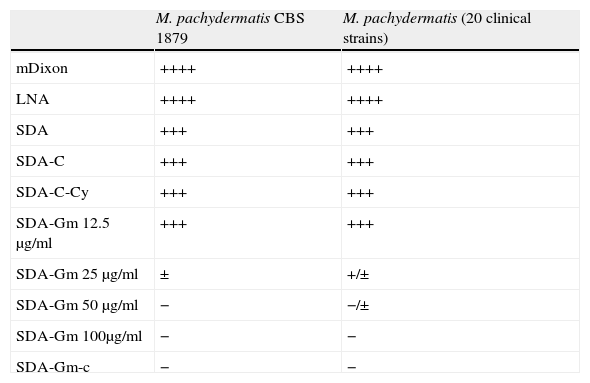

Twenty M. pachydermatis strains obtained by swabbing the external ear canals of dogs and CBS 1879 M. pachydermatis as the control strain were used for the study. A suspension of yeasts adjusted to about 105cells/ml was cultured on lipidic medium (modified Dixon) and on non-lipidic media containing Sabouraud agar with other ingredients and antimicrobial agents (Table 1). Plates were read after 5 days of incubation at 35°C. The cultures were examined every 24h for 7 days when the results were obtained.

Growth of M. pachydermatis on different mycological media (5 days, 35°C).

| M. pachydermatis CBS 1879 | M. pachydermatis (20 clinical strains) | |

| mDixon | ++++ | ++++ |

| LNA | ++++ | ++++ |

| SDA | +++ | +++ |

| SDA-C | +++ | +++ |

| SDA-C-Cy | +++ | +++ |

| SDA-Gm 12.5μg/ml | +++ | +++ |

| SDA-Gm 25μg/ml | ± | +/± |

| SDA-Gm 50μg/ml | − | −/± |

| SDA-Gm 100μg/ml | − | − |

| SDA-Gm-c | − | − |

mDixon: modified Dixon. LNA: Leeming and Notman medium [Leeming JP, Notman FH. Improved methods for isolation and enumeration of Malassezia furfur from human skin. J Clin Microbiol 1987; 25: 2017–9]. SDA: Sabouraud dextrose agar (Bio-Mérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). SDA-C: SDA-chloramphenicol (Bio-Mérieux). SDA-C-Cy: SDA with cycloheximide and chloramphenicol commercialized medium/gelose (Bio-Mérieux). SDA-Gm: SDA supplemented with gentamycin. SDA-Gm-c: Sabouraud commercialized plates (Sabouraud glucose agar with gentamycin, Bio-Mérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). ++++ Growth >50CFU, large colonies, >2mm. +++ Growth >30CFU, large colonies. +/± Sparse growth ≤30CFU, ≤2mm. ±/− No growth or sparse colonies (<5) and very small (<=1mm). − No growth.

Results are summarized in Table 1. Colonies consistent with M. pachydermatis were visible at 48 h on modified Dixon and at 72h on SDA and SDA-C-Cy plates. No colonies or quite small colonies were observed on SDA-Gm. Gentamycin at a concentration of 100mg/L inhibited all strains tested on SDA.

Gentamycin at high concentrations used in commercialized media (100mg/ml) effectively inhibits the growth of M. pachydermatis on SDA. Growth is also inhibited at other concentrations used in the market (40mg/L). This fact can lead to some important misdiagnoses if commercialized plates with gentamycin are employed: firstly, false-negative cultures, and secondly an erroneous classification of M. pachydermatis as a lipid-dependent species. According to our findings, high concentrations of gentamycin (>25mg/L) have a deleterious effect against M. pachydermatis and other species of Malassezia (personal observation). These findings could be useful in two therapeutic fields: (i) in animals, topical gentamycin could be an efficacious treatment for disease related to M. pachydermatis, and this can be especially convenient in infections where this yeast appears together with bacteria (such as EO in dogs); (ii) in humans, we hypothesize that gentamycin could be regarded as a possible therapy (“antibiotic-lock” or “antifungal-lock”) for catheter-associated Malassezia spp. infections.1,3,10 For the latter, gentamycin has important advantages, namely its wide action spectrum; its reputation and acceptance as one of the more well-known antimicrobial agent in this type of therapy, and finally its low cost.

We would like to thank Nick Thompson for his assistance in translating this manuscript into English.

Author's disclosure

Authors have nothing to declare.