Obesity in children and adolescents

The global burden of childhood and adolescent obesity is enormous, and currently 1 child in 10 is overweight or obese worldwide1. The International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) and the World Health Organization (WHO) have raised awareness of the magnitude of obesity and its impact on morbidity and mortality, quality of life, and cost of healthcare2.

In Europe, the highest estimates of overweight and obesity in older children aged 14-17 years, are highest in Cyprus, Spain, and the United Kingdom2. Data from Spain3 reveal an alarming increase in the prevalence of obesity in children and youth, with 14% of individuals classified as obese as defined by the 97th percentile4,5. This progressive boost has been shown in both overweight and obesity rates, in children and adolescents, since 1984 when PAIDOS study was carried out6. Results from the enKid study (1998-2000)3 already indicated a prevalence of 24.4% in overweight and 6.3% in obesity, meanwhile the AVENA study (2000-2002), indicated that 25.7% of male adolescents and 19.1% of female adolescents presented overweight or obesity7,8. It is of great concern that although it is clear that pediatric and adolescent weight problems exist, a large percentage of overweight and obese patients remain undiagnosed9.

Obesity is the consequence of an imbalance between energy expenditure, energy consumption, and energy storage in the body. It is a chronic disease characterized by an increase in body weight as a consequence of an increment in body fat7.

The etiology of obesity is multi-factorial since many genetic and environmental factors, and the interaction of both, are involved10. Obesity in adolescence is considered a complex syndrome with demonstrated physical, behavioral and social alterations. A link has been established between overweight and obesity to a lower quality of life, poor school performance, unhealthy practices such as smoking and alcohol consumption, physical inactivity and inappropriate dieting practices11-14.

Overweight and obese children and adolescents are at risk for significant health problems. They are likely to develop risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease, such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and T2DM (type 2 diabetes mellitus) and other related conditions associated with increased weight such as asthma, hepatic steatosis and sleep apnea15-17. Overweight and obesity places a long term higher risk for chronic conditions such as stroke, breast, colon, and kidney cancers, musculoskeletal disorders, and gall bladder disease16. It significantly increases the risk for adult obesity and for greater severity of obesity in adulthood17,18.

Management of childhood and adolescent obesity

Treatment for children and adolescents with overweight or obesity seems easy, that is, just advice children and their families to eat less and to exercise more19. In practice, however, treatment of childhood obesity is time-consuming, frustrating, difficult, and expensive19. This is especially true for primary care providers, who have limited resources to offer interventions within their offices or programs and few providers to whom they can refer patients20.

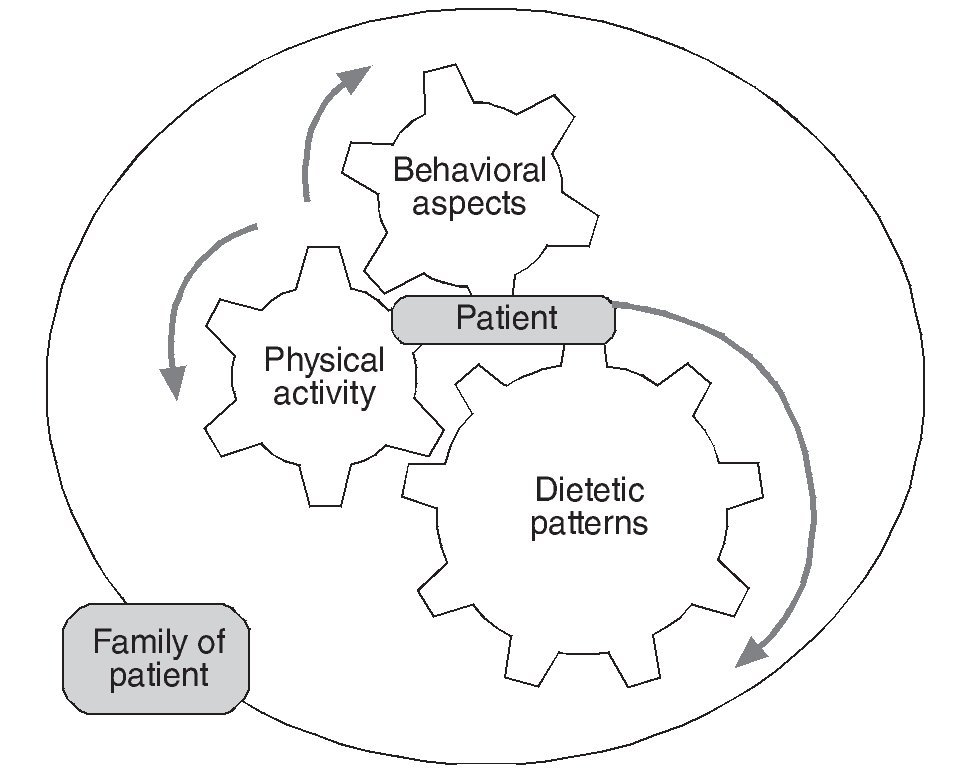

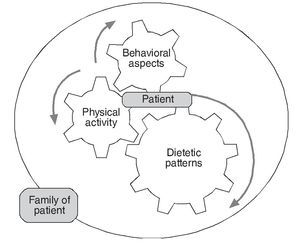

Numerous factors contribute to the development of adolescent obesity, including: genetics and environment, and others such as metabolic, biochemical, psychological and physiological aspects21,22. It is unlikely that one single-side intervention can be targeted to all these multi-causal agents; therefore, it must be a multi-disciplinary approach, where the patients as well as the family are both targets for the intervention, as illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1. Factors to be considered as part of an integral lifestyle intervention to be targeted in both patients and family.

So far, no trial has been able to clearly determine if specific dietetic interventions (without behavior interference or increased physical activity) are effective in the reduction of overweight and obesity. Interventions that include behavior therapy with dietetic and physical activity changes are widely used, and appear to be the most successful in improving long-term weight and health status23,24. Ultimately, children and adolescents (and adults, for that matter) become overweight or obese because of an imbalance between energy intake and expenditure. Dietary patterns, television viewing and other sedentary activities, and an overall lack of physical activity play key roles in creating this imbalance and therefore represent opportunities for intervention20.

Lifestyle influences

The long term impact of obesity treatments on the health of children and adolescents remains unclear21. This is the reason why more trials that evaluate promising interventions during more extended periods of time are urgently needed25. Although good quality pediatric and adolescent data are scarce, there is enough evidence that intensive lifestyle modification programs, like in adults, can be a useful tool to control weight gain in this group26.

Successful weight management, through lifestyle interventions, confers important intermediate-term health benefits to adults such as reducing the incidence of T2DM and improving cardiovascular fitness27. Weight loss should be encouraged in patients with severe obesity and significant comorbidites; body mass index (BMI) will decline as linear growth proceeds, and a reduction of fat mass, increase in lean body mass, and improvement in cardiovascular fitness has been demonstrated. One of the main goals of children and adolescent overweight and obesity treatment is the reduction or prevention of obesity associated comorbidities in future ages.

Dietary aspects and food-related factors involved in the onset of overweight and obesity

Food groups

Fruit and vegetables

Fruits and vegetables are low-energy-dense foods that contribute to satiety and satiation; they may also displace other high-energy-dense foods from the diet such as salty snacks or baked goods. Preparation of fruit and vegetables, which contributes to variation in energy intake, energy density, and macronutrient composition, modifies their effect in weight1.

Actual evidence indicates that greater fruit and vegetable intake may provide modest protection against increased adiposity20,28,29. Research indicates that children are least likely to consume adequate amounts of food from the fruit and vegetable groups compared with other food groups28. The Endocrine Society recommends increasing fiber, fruit and vegetable intake30. The Spanish Pediatric Association suggests an augment in fruit and non-fat dairy products in the morning and afternoon snacks31.

Fruit juice

Intake of 100% fruit juice does not seem to be related to childhood and adolescent obesity unless it is consumed in large quantities. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that fruit juice be limited to 120 to 150 g/day for children 1 to 6 years of age and 240 to 360 g/day for children 7 to 18 years of age29. Still, the important contribution to nutrient intake of 100% fruit juices has been stressed, considering it advantageous in adequate amounts in healthy children (taking into account the sugar content).

Sweetened beverages

Intake of soft drinks and sweetened fruit drinks has increased dramatically in recent years32-34. Although there is no clear evidence that consumption of sugar per se affects food intake and weight gain, there is evidence to suggest that "liquid sweets", or energy consumed as a liquid, may be less well regulated by the body than energy consumed in a solid form20.

Consuming excessive quantities of low-nutrient, energy-dense foods such as sugar-sweetened beverages are a risk factor for obesity22. Reducing intake of sugared beverages may be one of the easiest and most-effective ways to reduce ingested energy levels32.

Alcohol intake should be taken into account due to its high energetic density (7 kcal/kg). This fact is frequently ignored by adolescents. It is advised to use only water as main beverage, increasing its intake31.

Dairy foods and calcium

As early as 1984, it was reported that dietary calcium intake was related inversely to BMI in adults35. Recently, new publications have been published relating low dietary calcium intake to human adiposity19,36.

A potential role for calcium and dairy foods in the development of overweight and the potential for preventing weight gain by improving the dairy intake of youths has been suggested. The relative importance of calcium and dairy foods, in comparison with each other factors involved in the development of overweight remains to be established20.

Dietary fiber

Fiber is often a marker of a healthy diet37 and an inadequate consumption may contribute to excessive weight gain38. Dietary fiber may be related to body weight regulation through plausible physiologic mechanisms39 that include a slower rate of gastric emptying, reduced postprandial glycemic and insulinemic effects, and metabolism of short-chain fatty acids in the gut, that can reduce energy intake within and between meals17. There is considerable reason to conclude that fiber-rich diets containing non-starchy vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, and nuts may be effective in the prevention and treatment of obesity in children and adolescents. In children, an "age + 5" rule for dietary fiber intake has been recommended40. This means that a 5-year old child should consume at least 10 g of fiber per day and fiber intake should approach adult levels (20-25 g per day) by 15 years of age. Still, future research might separately consider different types of fibers to better understand the associations1.

Grains and ready-to-eat (RTE) breakfast cereal

RTE cereal is protective against weight gain and obesity in children, but prospective studies with better adjustment for potential confounders (dietary and otherwise) are needed; limited evidence supports a protective association of RTE cereal and whole grains on waist circumference1. There is strong evidence to conclude that whole grains are associated with lower body weight, smaller waist circumference, and less risk of obesity17.

Beans, legumes and soy

Protein-rich plant foods such as beans, legumes, and soy products play a special role in vegetarian and plant-based diets to meet human protein needs for growth and health1. Proteins from soy and other plant foods are higher in nonessential amino acids compared with proteins from animal foods; thus they may favorably affect insulin sensitivity41. There is insufficient evidence on the relationship between legumes and body weight in children and adolescents17,41.

Due to the important role these foods play, more research is warranted.

Macronutrient distribution modifications

Carbohydrates and fat

In the majority of child and adolescent population of Spain, the elevated intake of fat in expense of a low carbohydrate intake, disrupting diet energy distribution, is highlighted31. Although low carbohydrate diets may have some beneficial effects on risk factors for cardiovascular disease and T2DM42, the overall effects of this approach on other disease processes and on growth and development are unknown20.

A diet low in saturated fat and cholesterol is strongly recommended by the American Heart Association and the National Cholesterol Education Program as a way to prevent coronary heart disease. In addition, the National Cancer Institute has suggested that dietary fat restriction may also prevent the development of some cancers. It has been concluded that dietary fat restriction may have some small, but measureable, effects upon growth43.

Several culinary techniques have been recommended to help lower the amount of fats and carbohydrates in the diet, these include: to limit fried, lightly fried, battered and stewed foods; encourage the use of low-calorie seasonings such as parsley, garlic, pepper, mustard, nutmeg, and basil; avoid prepared soups and try to use virgin olive oil to cook and in salads31.

The glycemic index (GI) has also been proposed to affect body weight regulation and risk for obesity-associated complications44. Studies comparing the effects of high-GI versus low-GI diets on body weight in adults have produced conflicting results; some showed weight loss, others showed no difference in weight45.

It is important to consider the type of carbohydrate and fat to be employed in the recommended diet30.

Proteins

Evidence of long-term effectiveness (>1 year after treatment) of a high-protein, low carbohydrate diet is limited. A major concern with the use of these diets to treat childhood and adolescent overweight is that the very low energy intake may impair growth. The purpose of using these diets is to bring about rapid weight loss during the initial phase of treatment while minimizing the negative effects of a very-low-energy diet20. Still, some studies have shown that children and adolescents initially treated with a high-protein, low carbohydrate diet, were able to maintain some weight loss at 1 year46,47.

Additional aspects

Dietary interventions based on energy density also have been considered as an approach to weight management. A decrease in energy density decreases energy intake independent of macronutrient ratio, possibly because of effects on satiety48. Diets of low energy density, which are typically rich in vegetables, fruits, legumes, and minimally processed grain products, allow individuals to consume satisfying portions of food while reducing their energy intake. Decreasing the energy density but maintaining or increasing the volume of core foods in a weight management program may help decrease energy intake20.

Actual evidence for children and adolescents does not support any specific macronutrient or dietary strategy at this time19.

Food-related behaviors

Breakfast skipping

Overweight children and adolescents are now more likely to skip breakfast and consume a few large meals per day than their leaner counterparts who are more likely to consume smaller, more frequent meals49. The strength of the evidence is limited because what constitutes a breakfast has not been defined consistently20. Eating breakfast reduces snacking throughout the remainder of the day50. The Spanish Pediatric Association suggests: eating breakfast everyday; that breakfast and mid-morning snack should contribute to 25% of the total energy intake, and milk (dairy products), fruit and cereals should be included at breakfast. To avoid overeating episodes, the total number of meals per day should be no less than four. Energy intake should be distributed throughout the day as follows: 25% between breakfast and mid-morning snack; 30-35% for lunch; 15% for afternoon snack, and the rest for dinner31. Still, more studies are needed to confirm an association between meals, snacking and overweight.

Snacking

The American Dietetic Association found that snacking frequency or snack food intake might not be associated with adiposity in children23. Still, snacks tend to have higher energy density and fat content than meals, and frequent snacking has been associated with high intakes of fat, sugar and energy30. Strategies to manage increased hunger episodes include avoiding eating between meals and availability of low calorie foods31; other approaches include eating timely, regular meals, particularly breakfast (as aforementioned), and avoiding constant "grazing" during the day, especially after school30.

Eating out

Consuming food away from home, particularly at fast food establishments, may be associated with adiposity, especially among adolescents. Frequent eating at fast food establishments may be a risk factor for overweight/obesity in children and adolescents and fast food ingestion year after year may accumulate into larger weight gains that can be clinically significant51.

Portion control

Increased portion sizes parallels the increase in obesity52. Energy intake and portion sizes consumed both at home and away from home have increased between in 1977 and 199853. Portion control is commonly recommended to reduce the energy load of consumed foods. Strategies may include providing information on the energy content of regularly consumed foods, use of premeasured foods such as snack packs, and/or reducing the energy density of foods. These strategies may impact either the homeostatic and/or hedonic systems that regulate eating behavior.

Portion distortion is a new term created to describe the perception of large portions as appropriate amount to eat at a single eating occasion54. This distortion is reinforced by packaging, dinnerware, and inadequate or large serving utensils55. Portion control at meals and snacks should be included as part of a comprehensive weight management program to decrease energy intake and weight loss54.

Specific dietary patterns

Many different diets have been proposed for weight loss treatment. Currently there is a debate about whether a low-fat (usually 30% of calories as fat) or a low-carbohydrate diet is more efficacious. Some studies have shown a moderately greater weight loss by 6 months but not after 12 months with a low-carbohydrate diet56. There is insufficient pediatric and adolescent evidence to recommend any hypocaloric diet over another; when using unbalanced hypocaloric diets that may be deficient in essential vitamins and minerals, caution should be practiced30. In adults, recent data conclude that reduced calorie diets result in clinically meaningful weight loss regardless of which macronutrients they emphasize57.

Balanced-macronutrient/low-energy diets

Limited research exists for evaluating dietary treatment programs in isolation. Although outcomes are somewhat contradictory, evidence suggests that in both the short and long term, a reduced energy diet (less energy than required to maintain weight but not less than 1200 kcal/day) may be an effective part of a multidisciplinary weight management program58. Use of a reduced-energy diet (not less than 1200 kcal/day) in the acute treatment phase for adolescent overweight is generally effective for short-term improvement in weight status; without continuing interventions, however, weight is regained19. Very-low calorie diets (500-600 kcal) are scarcely used in pediatrics, since they are highly restrictive and can provoke growth stunting42,43. When indicated, in very specific patient situations such as severe obesity, they should be employed during short periods of time, under the strict supervision of specialists; therefore, they should never be applied in primary attention care31.

Objectives for weight loss in children and adolescents vary in function of the patient's age, evolution, outcome to previous treatments, and most importantly, the severity of obesity. Improvement in dietary habits leads to an improvement in body weight (weight loss or weight maintenance during growth) for some adolescents, but others are still in need of additional efforts to achieve a negative energy balance19. In moderate obesity, a nutritional intervention will be necessary in order to accomplish a negative energy balance in a way that it does not interfere with normal growth31. Evidence in children and adolescents does not allow for further recommendations.

Plant-based dietary patterns

Only two published studies have examined associations between empirically derived plant-based dietary patterns and obesity in children, and neither showed a protective effect18,59. Both studies were cross-sectional and adjusted for some potential confounders. Among adults, plant-based dietary patterns have been inversely associated with body weight and BMI in prospective studies60-62. Because foods are not consumed in isolation but, rather, as part of a total dietary pattern, more research with the use of these methods in children is required, and studies should be prospective. The lack of evidence showing and association between plan-based diets and childhood and adolescent obesity does not mean that such diets should not be encouraged. Because of the low-energy-dense and high-nutrient-dense nature of plant foods, a physiological association with lower body weight and decreased body fat is both plausible1. Vegetarian, semivegetarian, and vegan diets have been associated with lower risk of obesity in many studies in adult populations63. Care should be taken in planning strict vegetarian or vegan diets, especially those that are very low in fat43, to ensure adequate nutrient intakes to promote normal growth and development of children and adolescents1.

Traffic light diet

The traffic light diet was developed by Epstein et al64 for use in research on overweight. Because of the groundbreaking nature of their findings, this dietary regimen has become broadly recognized and in some cases copied. It is part of a large multi-component intervention that includes family components, physical activity, and interactions with behavioral therapist65,66.

The goal of the traffic light diet was to provide the most nutrition with the lowest energy intake. Daily energy intakes ranged from 900 to 1200 kcal, with later studies increasing intake to 1500 kcal/day66. Food groups were divided into three categories, namely, green, yellow, and red. Low energy, high-nutrient foods (most fruit and vegetables) are considered "green" and may be eaten often. Moderate-energy foods (most grains) are considered "yellow" and may be eaten in moderation, while high-energy, low-nutrient foods are considered "red" and should be eaten sparingly ( <4 times per week once children and families met their weight goals counseling was provided to ensure consumption of a balanced diet that would maintain healthy 20.

This program demonstrated modest sustained weight loss in 5 year old children64,65 even 10 years after the intervention66. It is still unclear what part of the diet itself played in these overall results.

Mediterranean style based diet

The Mediterranean diet (MD) is considered as one of the healthiest dietary models. It is regarded a prototype model for healthy eating and has generally been associated with longevity. Higher adherence to this regimen has been associated with better diet quality and nutrient intake in children and adolescents67. Moreover, two recently published studies concluded that the MD has a beneficial effect on asthma and allergy68.

Although studies on children and adolescents are limited and the majority of scientific publications refer to adults, promising evidence suggests that the MD may be a health-promoting factor for children and adolescents, as well. Further studies are needed in order to evaluate interventions based on the MD as opposed to more 'traditional' ones, which are based on current recommendations for pediatric nutrition69.

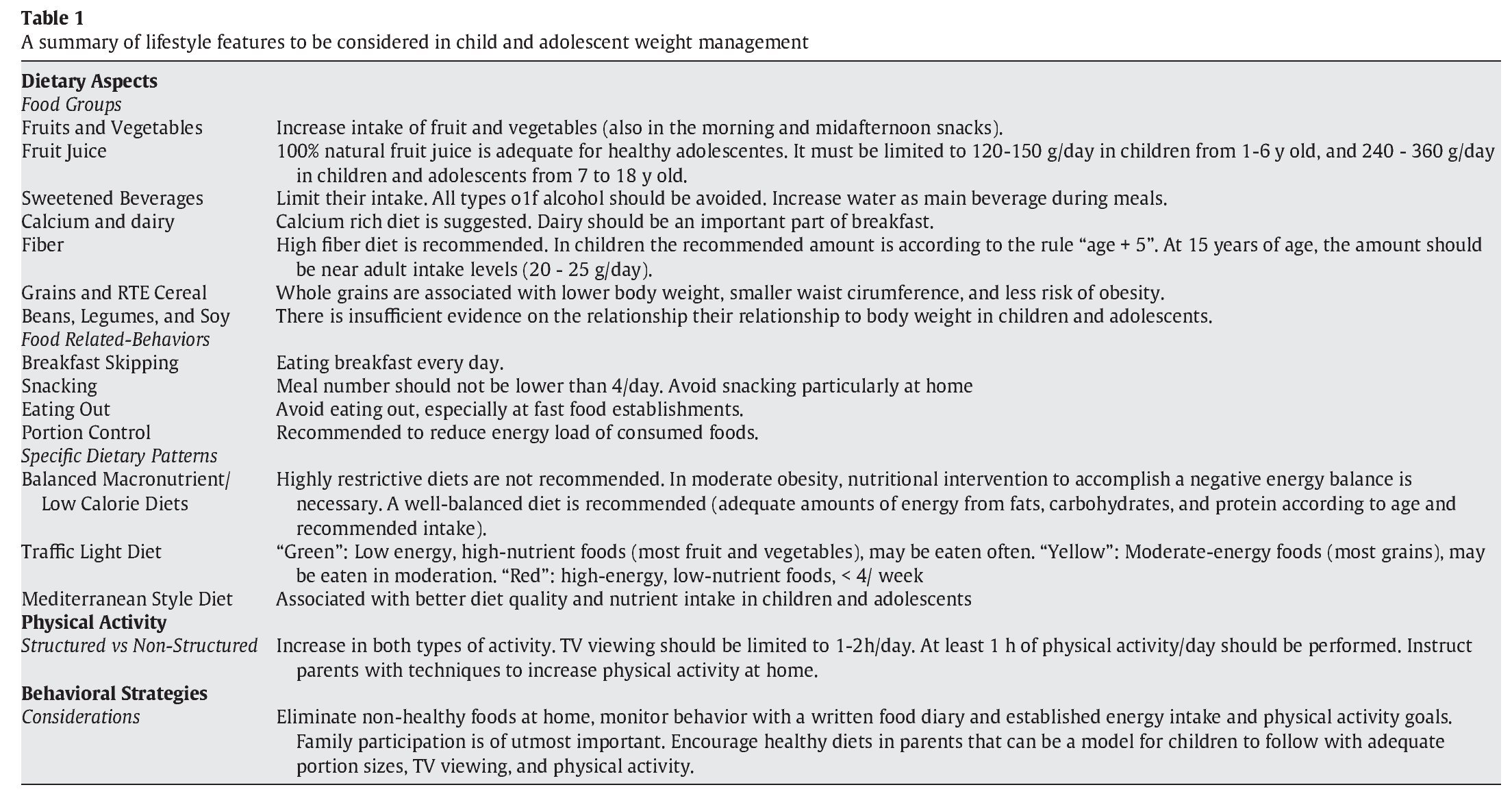

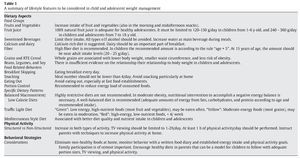

A summary of lifestyle features regarding child and adolescent overweight and obesity management, such as nutritional approaches, food associated behaviors, specific dietetic patterns, physical activity, and psychosocial strategies are presented on table 1.

Physical activity recommendations

Physical activity is the only modifiable component of the energy expenditure portion of the energy balance equation. However, in the absence of calorie restriction, moderate exercise does not generally cause weight loss. Consequently, in combination with decreased caloric intake, exercise can achieve significant weight loss20,30.

An increase in sedentary activities, particularly television viewing, and an overall decrease in physical activity contribute to an increased incidence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents24,70. Sedentary activities also encourage an increased food and energy intake, as an accompaniment to television viewing and as a result of food advertising. Several studies have indicated that television viewing has substantial effects on other risk factors for chronic disease, including smoking13, reduced fruit and vegetable consumption71, increased aggression13,72, and less time spent reading and doing school homework73.

Physical fitness

Physical activity may play a role in preventing weight gain and other health problems. Physical fitness, even without weight loss, may offer some health benefits. Physical fitness can be thought of as an integrated measure of most, if not all, the body functions (skeletomuscular, cardiorespiratory, hematocirculatory, psychoneurological, and endocrine-metabolic) involved in the performance of daily physical activity and or/physical exercise74. The role of poor physical fitness as a cardiovascular risk factor is even greater than other well established factors, such as dyslipidemia, hypertension or obesity27. Studies have shown an association between the level of physical fitness during childhood and adolescence and cardiovascular risk factors75,76. It is estimated that 1 in 5 Spanish adolescents have a level of physical fitness indicative of future cardiovascular risk27. Physical fitness is in part genetically determined, but it can also be greatly influenced by environmental factors. Physical exercise is one of its main determinants.

Physical fitness, physical exercise and physical activity are sometimes used as interchangeable concepts in the literature, which is not always appropriate77. Physical fitness is the capacity to perform physical activity, and makes reference to a full range of physiological and psychological qualities. Physical activity is any body movement produced by muscle action that increases energy expenditure, whereas physical exercise refers to planned, structured, systematic and purposeful physical activity78.

Health-related physical fitness components

Cardiorespiratory fitness is the overall capacity of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems and the ability to carry out prolonged strenuous exercise78.

Muscular fitness is the capacity to carry out work against a resistance. There is no single test for measuring muscle strength. The handgrip test is one of the most used tests for assessing muscular fitness in epidemiological studies78. Also, the jump test and bent-arm hang test have been widely used in young people for assessing strength27.

Physical fitness and health outcomes

The latest developments with regard to physical fitness and several health outcomes in young people suggest that: a) cardiorespiratory fitness levels are inversely associated with total and abdominal adiposity; b) both cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness are shown to be associated with established and emerging cardiovascular disease risk factors; c) improvements in muscular fitness and speed/agility, rather than cardiorespiratory fitness, seem to have a positive effect on skeletal health; d) both cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness enhancements are recommended in pediatric cancer patients/survivors in order to attenuate fatigue and improve their quality of life, and e) improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness have positive effects on depression, anxiety, mood status and self-esteem, and seem also to be associated with a higher academic performance74.

Physical activity and weight management

Physical activity has less impact on weight loss than dietary intervention since it is easier to reduce energy intake by 500-100 kcal/day than to increase energy expenditure by a similar amount.

Structured vs. nonstructured physical activity

Nonstructured physical activity comprises all normal day activities for an individual, such as play, walking, assistance to class, time spent on the computer and television, all influenced by lifestyle. Structured physical activity includes intense, planned, structured and repeated activity in order to accomplish a good physical shape; providing an extra increase in energetic expenditure. It is usually performed during short periods of time, and it may not necessarily affect energetic stores if the individual presents alternation with prolonged periods of low activity, not modifying total energy expenditure6.

An increase in both types of physical activity is recommended. The development of a physically active lifestyle should be a goal for all children and adolescents. It is thought that increasing the frequency or intensity of physical activity can reduce sedentary activities, particularly television viewing. This can reduce excess energy balance effectively. The goal is not to eliminate television watching; data suggest that children and adolescents can engage in both television viewing and physical activity as long as sedentary activity is not at the expense of physical activity20,30,79.

Amount of physical activity

General guidelines79 advice that a) all children and adolescents meet the goal of 60 min of moderate activity per day; b) schools be provided with the necessary resources to incorporate 30 min of moderate to intense activity into each student's daily schedule, and c) clinicians should instruct parents on techniques for increasing activity in the home environment, including reducing time spent in sedentary activities.

It is important to consider that overweight children and adolescents may experience negative consequences of participation in activities considered appropriate for normal-weight children. Activities that are easily performed should be considered. Recommendations based on clear, attainable goals that gradually increase in volume and intensity over time should be established. Such structuring will help ensure that overweight children experience initial success. Because overweight children will expend more energy performing exercise of the same intensity as normal weight children, they should not be prescribed running activities in which they must compete with normal-weight youth. Resistive weight-lifting exercise activity should be performed under the close supervision of trained personnel16.

Behavioral strategies

It is recommended that clinicians prescribe and support intensive lifestyle (including behavior) modification to the entire family and to the patient, in an age-appropriate manner (fig. 1), and as the prerequisite for all overweight and obesity treatments for children and adolescents30.

The role of parent-child/adolescent interactions and parenting style in the development of unhealthy lifestyle habits is a subject of investigation25,30,80. An additional factor that must be taken care of before initiating any intervention could be the ability of parents or caregivers to take into account their child's or adolescent's weight problem. Parents should be educated to avoid using food as a punishment or compensation tool. Parents are role models and figures of authority to further mold healthy habits in children.

Goals

The purpose of the behavior assessment has mainly two objectives. The first goal is to identify the patient's dietary and physical activity behaviors that may promote energy imbalance and that are modifiable. The second goal is to assess the capacity of the patient and/or the patient's family to change some or all of these behaviors. Families should have both the means and the motivation to make changes19.

Techniques

Behavioral therapy for pediatric and adolescent obesity uses a number of techniques that modify and control children's food and activity environments in ways that bring about weight loss. These techniques include removing unhealthy foods from the home, monitoring behavior by asking children or parents to keep track of the food consumed, setting goals for energy consumption and physical activity, and rewarding children's and sometimes parent's successful changes in diet and physical activity. Additional behavioral approaches include training in problem solving and other parenting skills20,81.

A number of behavioral techniques, including environmental control approaches (such as parental modeling of healthful eating and physical activity), as well as monitoring, goal setting, and contingency management, can facilitate recommended changes81.

Several researchers have addressed a key question, that is, who should be the target for change? Including parents as agents of change seems critical for success, particularly for younger children20,64-66. The evidence on the amount and type of parental involvement in adolescents' weight control is still inconsistent20.

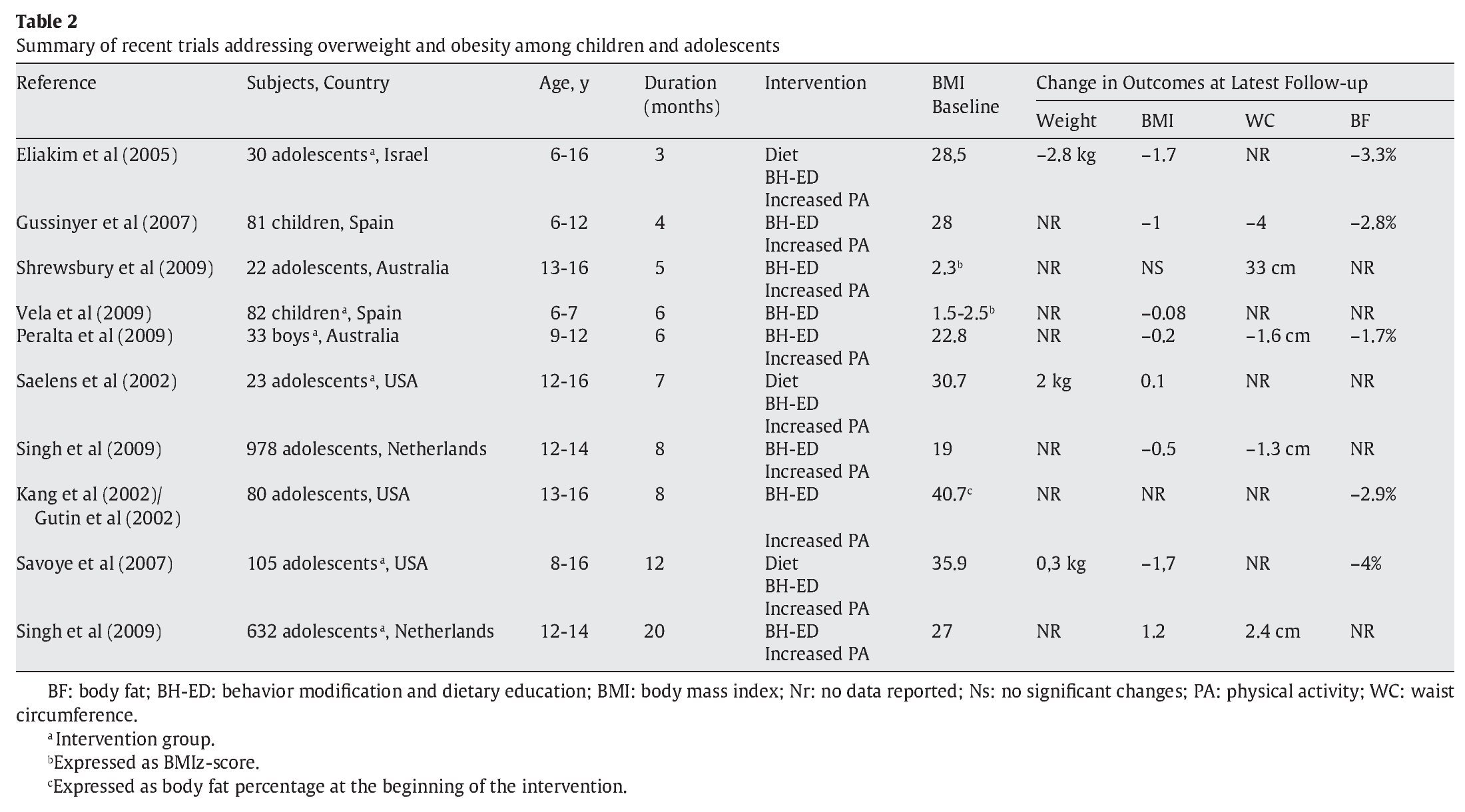

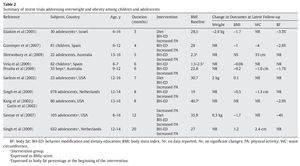

A general summary of meta-analyses of randomized trials for dietary, physical activity, and combined lifestyle interventions is shown in table 2, proving that integral lifestyle interventions seem to be the most effective.

Conclusions

The prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents is still too high and represents a pool of latent morbidity, because >50% of obese children and 70-80% of obese adolescents will become obese adults82. However, there is much to consider before concluding what is the best option in addressing the problem. According to evidence, what seems to be the most successful approach is intensive lifestyle modification that includes guidance on dietary aspects, food-related factors, physical activity, and behavioral strategies. Family support is of outmost importance. All of these considerations are essential for developing and implementing preventive measures specifically directed toward children and adolescents.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

* Corresponding author.

E-mail: amarti@unav.es (A. Martí).

INFORMACIÓNDEL ARTÍCULO

Historia del artículo:

Recibido el 25 de noviembre de 2009

Aceptado el 9 de diciembre de 2009