In many forensic investigations into cases of cyberbullying and online violence against minors, video footage can serve as crucial evidence, as it allows the identification of the perpetrator's physical features. Although the face is often concealed, other parts of the body are frequently exposed and can be revealing.

ObjectiveThis study analyzes the horizontal linear folds (HLFs) on the dorsal aspect of the proximal interphalangeal joint (PIPJ) of the dorsum of the hands as a unique anatomical feature for human identification with legal value in forensic medicine.

Material and methodsReal and ideal scenarios were performed to obtain doubtful and doubtless images of the dorsal hands by a webcam and a high-resolution camera, respectively. The presence and number of HLF from 112 dorsal PIPJs (4 fingers, 2 hands, 14 individuals) were quantified and statistically compared by analyzing the similarity between sample groups using Sorensen-Dice coefficient and Jaccard index.

ResultsHLF resulted in a sensitivity (positive identification) of 78.57%, but a specificity (negative identification) of 26.1% (area under ROC curve = 55.3%). Visual inspection of doubtful and doubtless samples achieved a 100% match in human identification.

ConclusionsThe morphological variability and unique pattern of the HLF can be used as a simplified method to delimit human identification in forensic medicine.

En muchas investigaciones forenses sobre casos de ciberacoso y violencia en línea contra niños, niñas y adolescentes, los vídeos pueden representar una evidencia crucial, ya que permiten identificar características físicas del agresor. Aunque este suele ocultar su rostro, a menudo quedan al descubierto otras partes del cuerpo que pueden ser reveladoras.

ObjetivoEste estudio analiza los pliegues lineales horizontales en la cara dorsal de la articulación interfalángica proximal del dorso de las manos como una característica anatómica única para la identificación humana con valor legal en medicina forense.

Material y métodosSe realizaron escenarios reales e ideales para obtener imágenes dubitadas e indubitadas del dorso de las manos mediante una webcam y una cámara de alta resolución, respectivamente. Se cuantificaron la presencia y el número de pliegues lineales horizontales de 112 PIPJ (4 dedos, 2 manos, 14 individuos) y se compararon estadísticamente analizando la similitud entre los grupos de muestras mediante el coeficiente de Sorensen-Dice y el índice de Jaccard.

ResultadosLos pliegues lineales horizontales dieron como resultado una sensibilidad (identificación positiva) del 78,57%, pero una especificidad (identificación negativa) del 26,1% (área bajo la curva ROC = 55,3%). La inspección visual de muestras dubitadas e indubitadas logró una coincidencia del 100% en la identificación humana.

ConclusionesLa variabilidad morfológica y el patrón único de los pliegues lineales horizontales pueden utilizarse como método simplificado para delimitar la identificación humana en medicina forense.

Digital technologies have generated an abuse of cybercommunication and virtual interaction through dark social media platforms which, precisely because of their simplicity, versatility, globality and impunity, are constantly.1,2 Under the umbrella of these technologies operating from anywhere in the world and involving physical delocalization enabled by the virtual environment, a new form of cybercrime including crimes against sexual freedom and indemnity of minors has emerged.3 A major common factor is physical and virtual anonymity, posing a real challenge to law enforcement agencies in identifying and pursuing perpetrators and, therefore, bringing them to justice.

In a significant number of cases, the perpetrators belong to the social or familiar environment of the minor,4 a fact that allows forensic investigators to establish priority lines of investigation. Optimal audiovisual material is usually available and can provide valuable information about the circumstances surrounding the abuse.5–9 However, while the perpetrator's face is usually hidden or unintelligible,10 other parts of the anatomy are uncovered, often their hands.

The analysis of multiple anatomical features of the hands is becoming an increasingly common technique used by forensic investigators to identify perpetrators in cases involving child sexual abuse material.11 Dorsal hand traits such as fingerprints, scars, birthmarks, tattoos and veins can be used to establish a link between the suspect and the images or videos, or to rule out suspects who may have been falsely accused.12–14

Knuckle creases on the dorsal aspect of the fingers associated with the metacarpophalangeal (MCPJ) joint, the proximal interphalangeal joint (PIPJ) and the distal interphalangeal joint (DIPJ) are anatomical features that, due their embryological origin, their unchanging nature and their unique patterns during lifetime, can be used to determine the accuracy of the technique in the establishment of identity and to differentiate between individuals.15,16 However, the research methods proposed for dorsal knuckle fold analysis are not conclusive for forensic human identification. Some of the issues stem from the comparison of images of perpetrators' hands, usually taken in non-standard positions and different capture conditions, as well as the impact of finger flexion to visualize knuckle creases.17

Conclusive human identification is crucial for criminal-legal purposes. While methods like dental records, DNA analysis and fingerprints are commonly used,14,18,19 they may not always be available. Therefore, it is important to find refined approaches of digital image analysis and sensitive markers of the hand traits for forensic human identification. In this study, we mimicked real and ideal scenarios to obtain doubtful and doubtless images of dorsal hands in a more kinetic position using a webcam and a high-resolution camera, respectively. Doubtful and doubtless images were used to investigate similarity (coincidence) in the presence and number of horizontal linear folds (HLFs) on the dorsal aspect of the PIPJs, as an individual morphological feature of the dorsum of the hands. We propose that this relatively simplified approach can be easily used as a reliable method in forensic medicine to facilitate human identification with criminal-legal value.

Material and methodsHuman ethics and consent to participateThe study was conducted with the approval of the Ethics Committee of University of Malaga (CEUMA ref. no. 95-2023-H) in accordance with the Ethical Principles involving Human Subjects adopted in the Declaration of Helsinki and Spanish law on data protection. All the subjects signed informed consent forms after receiving a complete description of the study. All participants had the opportunity to discuss any questions or problems. Data collected were assigned random code numbers to maintain privacy and confidentiality.

Experimental designThe hands of 14 adult individuals (7 males and 7 females) with no history of injuries or hand surgery, and no skin disease or condition were selected. The dorsum of both hands of each individual was photographed following real and ideal scenarios to obtain doubtful and doubtless samples, respectively:

- (1)

To obtain doubtful samples, a real scenario of the criminal acts of interest was performed as follows (Supplementary Fig. 1A): All participants were seated in front of a laptop computer on which an AUKEY webcam (model 1080 Full HD) was installed. Participants adopted the same body posture and placed both hands on the keyboard in three positions: extension (00), semi-flexion (450) and with the fingers holding a cylinder (Supplementary Fig. 1B), following previous studies.17 The end of the fingers was placed on the same keyboard keys. The horizontal linear folds on the dorsal aspect of the PIPJs were clearly observed in extension. Doubtful images of extended fingers were obtained with the webcam at a resolution of 96 dpi and a dimension of 1920x1080 pixels. This first set ofphotographs constituted the doubtful sample group P1.

- (2)

To obtain doubtless samples, an ideal scenario of optimal environmental conditions was created as follows (Supplementary Fig. 1C): All participants were seated in front of a photographic setup and adopted the same body posture. Participants placed their hands on the platform of the photographic support on which a Nikon D-80 reflex camera with AF-S NIKKOR 18–135 mm DX lens was installed. The photographs were obtained with optimal lighting and conditions adjusted to the criteria established by the Spanish Forensic Science Police Headquarters for facial mapping studies. High-resolution images of both hands were obtained in three positions: extension (00), semi-flexion (450) and with the fingers holding a cylinder (Supplementary Fig. 1D). The end of the fingers was placed in the same location. As in the previous scenario, the horizontal linear folds on the dorsal aspect of the PIPJ were clearly observed in extension. Doubtless images of extended fingers were obtained with the high-resolution camera at a resolution of 96 dpi and a dimension of 3168 × 4752 pixels. This second set of photographs constituted the doubtless sample group P2.

All the doubtful and doubtless images were obtained on the same day by moving the participant from real scenario to ideal scenario, and assigning for each sample random code numbers, one for the doubtful scenario (P1-X) and another for the doubtless scenario (P2-X). Finally, the horizontal linear folds on the dorsal aspect of the PIPJs of each finger observed from doubtful and doubtless images were quantified and statistically analyzed. To minimize the biases, observer 1 performing the real scenario is different to observer 2 performing the ideal scenario, so observers 1 and 2 involved in the real scenario did not know the code numbers assigned to the participant in the ideal scenario, and vice versa. In addition, none of the observers 1 and 2 involved in real and ideal scenarios participated in the posterior statistical analysis of the images.

Quantitative analysis of sampleTwo additional observers analyzed the knuckle creases on the dorsal aspect of the PIPJs of all fingers (excepting thumbs) of both hands of the 14 individuals. Thumbs were excluded due to unique positioning and difficult imaging. Among a total of 224 dorsal PIPJs analyzed, 112 of them belonged to doubtful samples P1 (first set of photographs) obtained in the real scenario and the other 112 belonged to doubtless samples P2 (second set of photographs) obtained in the ideal scenario. Horizontal linear folds comprised skin creases situated at right angle to the long axis of the finger.16 Complete and partial segments of the horizontal linear folds were distinguished based on their length. Those segments that did not cross more than 50% of the knuckle width were considered partial folds. Discrepancies, if any, were resolved between observers. Since horizontal linear folds were the most prevalent,16 vertical and oblique folds were excluded in the present study to reduce complexity of the analysis (lower consistency and discriminative value). Finally, in each image, the outline of complete and partial horizontal linear folds of the dorsal PIPJs that were clearly visualized by both observers was digitally drawn with blue lines by hand on a computer using GIMP 2.10 software. The presence and number of complete and partial horizontal linear folds were then quantified and statistically compared by matching doubtful (P1) and doubtless (P2) images.

The quantitative morphological comparison between the doubtful (P1) and doubtless (P2) samples was performed by similarity (coincidence between P1 and P2) in the presence and number of HLF. Similarity was measured using the Sorensen-Dice coefficient: J(A,B) = 2(|A∩B|/(|A| + |B|)), and the Jaccard index: J(A,B) = |A∩B|/|AUB|, where A and B represent samples P1 and P2, respectively, |A∩B| represents the intersection or coincidence of the presence and number of folds in the samples P1 and P2, and |AUB| represent the union (|A| + |B| − |A∩B|) of the presence and number of folds in the samples P1 and P2. Sorensen-Dice coefficient and Jaccard index are commonly used metrics for assessing pairwise image similarity in medical applications.20

Statistical analysisData in tables are expressed as numbers and percentage of subjects [N (%)]. A logistic regression model was performed to determine the coincidence between doubtful P1 and doubtless P2 samples in the presence and number of HLF assessed by Sorensen-Dice coefficient (SD presence or SDP, and SD number or SDN) and Jaccard index (J presence or JP and J number or JN). The variables introduced in the model were SDP, SDN, JN and JD. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, sensitivity and specificity of final model were obtained to determine the threshold for human identification from doubtless (P2) samples. Statistical analyses were carried out using STATA Statistic software version 18.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

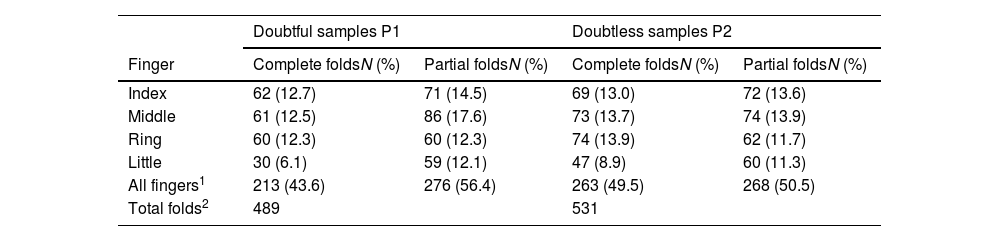

ResultsDescription of the sampleOf the 14 individuals studied, all had HLF in the dorsal PIPJs analyzed in the fingers (excepting thumbs) of both hands. A higher number of total HLF were counted in the doubtless (P2) samples compared to the doubtful (P1) samples (Table 1). Among a total of 489 HLF in the doubtful (P1) samples, folds were complete in 43.6% and partial in 56.4%. Among a total of 531 HLF in the doubtless (P2) samples, folds were complete in 49.5% and partial in 50.5% (Table 1).

Distribution of horizontal linear folds on each finger in doubtful P1 and doubtless P2 samples.

| Doubtful samples P1 | Doubtless samples P2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finger | Complete foldsN (%) | Partial foldsN (%) | Complete foldsN (%) | Partial foldsN (%) |

| Index | 62 (12.7) | 71 (14.5) | 69 (13.0) | 72 (13.6) |

| Middle | 61 (12.5) | 86 (17.6) | 73 (13.7) | 74 (13.9) |

| Ring | 60 (12.3) | 60 (12.3) | 74 (13.9) | 62 (11.7) |

| Little | 30 (6.1) | 59 (12.1) | 47 (8.9) | 60 (11.3) |

| All fingers1 | 213 (43.6) | 276 (56.4) | 263 (49.5) | 268 (50.5) |

| Total folds2 | 489 | 531 | ||

The distribution of the complete and partial folds was different for each finger (Table 1). The highest percentage of complete folds was found on the index finger of the P1 samples (12.7%) and the ring finger of the P2 samples (13.9%), while the lowest percentage was found on the little finger of both P1 and P2 samples (6.1% and 8.8%, respectively). The percentage of partial folds was higher on the middle finger of both P1 and P2 samples (17.6% and 13.9, respectively) and lower on the little finger of both P1 and P2 samples (12.1% and 11.3%, respectively). Absence of complete or partial folds were most common on the little finger and least common on the middle finger (Table 1).

Statistical analysis (chi-square test) on the number of horizontal linear folds indicated that there was no association between: (1) finger (index, middle, ring and little) and fold type (complete and partial) in any of the P1 and P2 sample groups; (2) image quality (P1 and P2 samples) and fold type (complete and partial) in a finger-independent manner; and (3) image quality (P1 and P2 samples) and finger (index, middle, ring and little) in a fold type (complete and partial)-independent manner.

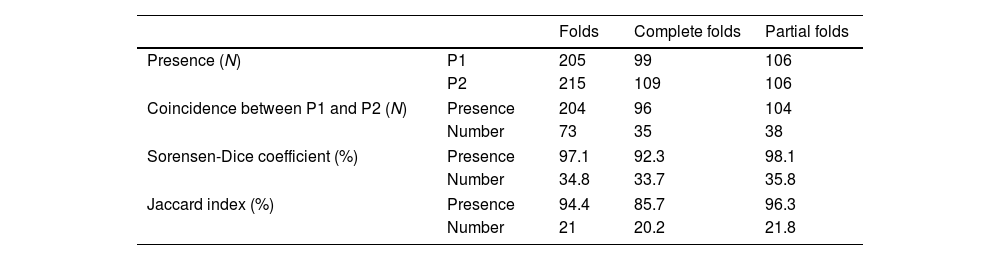

Quantitative identification of individuals by similarity of horizontal linear foldsAn analysis of the 224 dorsal PIPJs (8 fingers, two hands, 14 individuals) was performed to assess the overall similarity (coincidence between two compared samples) in terms of presence and number of HLF between the doubtful (P1) and doubtless (P2) samples obtained in the scenario 1 and scenario 2, respectively (Table 2). In the doubtful samples P1, horizontal linear folds in PIPJs were observed a total of 205 times, whereas 99 PIPJs had complete folds and 106 PIPJs had partial folds. In the doubtless samples P2, HLFs were observed a total of 215 times, whereas 109 PIPJs had complete folds and 106 PIPJs had partial folds. Coincidence of the presence of HLF in the PIPJs between the doubtful and doubtless samples was established 205 times (complete folds in 96 PIPJs, partial folds in 104 PIPJs). Coincidence of the number of HLF in the PIPJs between the doubtful P1 and doubtless P2 samples was established 73 times (complete folds in 35 PIPJs, partial folds in 38 PIPJs). Based on these data, overall similarity in the presence and number of HLF in the PIPJs between the doubtful and doubtless samples was assessed by Sorensen-Dice coefficient and Jaccard index (Table 2).

- •

The overall similarity in the presence of folds between the doubtful P1 and doubtless P2 samples was 97.1% (complete folds in 92.3% and partial folds in 98.1%), as Sorensen-Dice coefficient, and 94.4% (complete folds in 85.7% and partial folds in 96.3%), as Jaccard index.

- •

The overall similarity in the number of folds between the doubtful P1 and doubtless P2 samples was 34.8% (complete folds in 33.7% and partial folds in 35.8%), as Sorensen-Dice coefficient, and 21% (complete folds in 20.2% and partial folds in 21.8%), as Jaccard index.

Overall similarity between doubtful (P1) and doubtless (P2) samples in terms of coincidence of the presence and number of horizontal linear folds (HLF).

| Folds | Complete folds | Partial folds | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence (N) | P1 | 205 | 99 | 106 |

| P2 | 215 | 109 | 106 | |

| Coincidence between P1 and P2 (N) | Presence | 204 | 96 | 104 |

| Number | 73 | 35 | 38 | |

| Sorensen-Dice coefficient (%) | Presence | 97.1 | 92.3 | 98.1 |

| Number | 34.8 | 33.7 | 35.8 | |

| Jaccard index (%) | Presence | 94.4 | 85.7 | 96.3 |

| Number | 21 | 20.2 | 21.8 | |

To determine a potential human identification, similarity in the presence and number of HLF between each doubtful P1 and doubtless P2 sample was individually determined by the analysis of Sorensen-Dice coefficient and Jaccard index. Similarity was different for each doubtful P1 sample (Table 3). Taking together the presence and number of HLF in the PIPJs, the highest percentages of similarity were indicated in each doubtful P1 sample, resulting in a putative identification of doubtless P2 samples. Maximal coincidence was found in the doubtful samples P1.1 and P1.11 with respect to the doubtless samples P2.6 and P2.14, respectively. No coincidence was found in the doubtful sample P1.3 with any of the 14 doubtless P2 samples (Table 3).

Individual similarity in each doubtful (P1) compared to all doubtless (P2) samples in terms of the presence and number of horizontal linear folds (HLF).

| Sorensen-Dice coefficient (%) | Jaccard index (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doubtful (P1) samples | Presence | Number | Presence | Number | Probable doubtless (P2) samples |

| 1 | 96.3 | 74.1 | 92.9 | 58.8 | 6 |

| 2 | 96.8 | 38.7–32.3 | 93.8 | 24–19.2 | 4, 7, 8 |

| 3 | 100–89.7 | 53.3–6.7 | 100–81.3 | 36.4–3.4 | N.C. |

| 4 | 92.9–89.7 | 34.5–13.8 | 86.7–81.2 | 16.7–7.4 | 4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 15 |

| 5 | 92.9 | 35.7 | 86.7 | 21.7 | 3, 12 |

| 6 | 96.8 | 38.7–32.3 | 93.8 | 24–19.2 | 3, 9, 10, 12 |

| 7 | 100–96.8 | 56.3–25.8 | 100–93.8 | 39.1–14.8 | 1, 2, 7, 9, 11, 13 |

| 8 | 100 | 64.5–50 | 100–93.8 | 47.6–33.3 | 4, 5, 12 |

| 9 | 100 | 56.3–31.3 | 100 | 39.1–18.5 | 1, 4, 7, 8, |

| 10 | 100 | 62.5–43.8 | 100 | 45.5–28 | 4, 5, 13 |

| 11 | 93.3 | 46.7 | 87.5 | 30.4 | 14 |

| 12 | 88.9–85.7 | 59.3–21.4 | 80–75 | 42.1–12 | 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14 |

| 13 | 100–93.3 | 45.2–40 | 100–87.5 | 29.2–25 | 3, 4, 7, 9, 11, 13 |

| 14 | 96.6 | 55.2–34.5 | 93.3 | 38.1–20.8 | 9, 12 |

N.C., no coincidence. Bold numbers indicate identification of doubtless P2 samples.

Using likelihood-ratio tests, the variables in the final model were restricted to SDN, SDP, and JP. The final model had a sensitivity (true positive rate) of 78.6% to correctly identify doubtful P1 samples from doubtless P2 samples (matches between P1 and P2 samples), and a specificity (true negative rate) of 26.1% to correctly discard doubtful P1 samples from doubtless P2 samples (no matches between P1 and P2 samples). The cut-point value was ≥0.062. ROC analysis (AUC = 0.557; standard error = 0.059; 95% confidence interval = 0.50–0.60) indicated a modest discrimination power of human identification. The predicted probability of matching doubtful P1 and doubtless P2 samples is defined using the following formula: Log(P/1 – P) = 0.0088∙SDN + 0.4128∙SDP – 0.2218∙JP – 21.85.

Visual identification of individuals by comparing doubtful and doubtless samplesTo further determine individual identification, two forensic science officers performed a double-blinded analysis by comparing doubtful P1 samples and doubtless P2 samples, previously selected from the quantitative analysis of individual similarity (see previous Table 3). Both officers obtained a total correspondence (100%) between doubtful and doubtless samples, suggesting a conclusive human identification of the 14 individuals (Table 4, Supplementary Fig. 2).

Visual inspection between doubtful (P1) and doubtless (P2) samples.

| Double-blinded inspection | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 samples | P2 samples(selected from Table 3) | Officer 1 | Officer 2 | Identification |

| 1 | 6, 8, 9 | 6 | 6 | Yes |

| 2 | 4, 7, 8 | 8 | 8 | Yes |

| 3 | All samples | 9 | 9 | Yes |

| 4 | 4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13 | 7 | 7 | Yes |

| 5 | 3, 11, 12 | 3 | 3 | Yes |

| 6 | 3, 9, 10, 12 | 10 | 10 | Yes |

| 7 | 1, 2, 7, 9, 11, 13 | 2 | 2 | Yes |

| 8 | 4, 5, 12 | 4 | 4 | Yes |

| 9 | 1, 4, 7, 8, | 1 | 1 | Yes |

| 10 | 4, 5, 13 | 5 | 5 | Yes |

| 11 | 7, 8, 14 | 14 | 14 | Yes |

| 12 | 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14 | 13 | 13 | Yes |

| 13 | 3, 4, 7, 9, 11, 13 | 11 | 11 | Yes |

| 14 | 9, 12, 14 | 12 | 12 | Yes |

Bold numbers indicate identification of doubtless P2 samples.

The present study was designed to analyze the HLF of the dorsal creases of the PIPJs of the hands as a simplified method to facilitate human identification with legal value in forensic medicine. To this aim, two groups of samples (doubtful and doubtless images) were provided for detailed analysis of similarity of the presence and number of HLF in the dorsal PIPJs. The doubtful images (P1 samples) were obtained using a webcam installed on a laptop computer (scenario 1). Doubtless images (P2 samples) were obtained using a high-resolution camera with optimal lighting and conditions (scenario 2). In both scenarios, hands adopted the same kinetic position with the fingers in extension placed in the same location. Although optimal imaging conditions are often far from real-case testing, the experiment was designed to minimize discrepancies in non-standard position and flexion. In this regard, the doubtless images are representative of the kinetic position usually adopted by the fingers on the keyboard in the doubtful image. Using fingers in extension, HLFs of the dorsal PIPJs were clearly observed and delineated. Following the exclusion criteria of no history of injuries and hand surgery, the hands of 14 individuals were finally selected.

As expected through initial observations, the presence and number of HLF were lower in doubtful P1 samples than those in doubtless P2 samples (489 vs 531 folds), suggesting an effect of image quality (1920 × 1080 vs 3168 × 4752 pixels). The reduced image quality in the doubtful samples can be consistent with a decrease in the total number of folds detected. Although there was an overall decrease in complete and partial folds in all analyzed fingers of the doubtful samples, the result of the statistical analysis indicated that there was no significant difference in the association between image quality (P1 and P2 samples) and fold type (complete and partial). The same result was obtained when statistical analysis was separately performed in each finger (index, middle, ring and little) and each fold type (complete and partial). These results suggest that the number of HLF delineated in the doubtful and doubtless images does not limit the viability of the feature for comparison. When the sample group (P1 and P2) was analyzed independently, no association was found between finger type and fold type, suggesting that complete and partial folds are equally distributed on each finger.

A first result of the present study indicates that, based on the analysis of Sorensen-Dice coefficient and Jaccard index of similarity of the presence and number of the HLF, there was a variable rate of coincidence between doubtful and doubtless images in the 14 individuals, ranging from total coincidence (perfect match) observed in the doubtful samples P1.1 and P1.11 to no coincidence (no match) observed in the doubtful sample P1.3. A second result indicates that logistic regression analysis of the presence and number of HLF assessed by Sorensen-Dice coefficient (SDP and SDN) and Jaccard index (JP and JN) was able to define a predictive model containing the variables SDP, SDN and JN. This model resulted in a sensitivity of 78.57% to correctly identify doubtful P1 samples from doubtless P2 samples, but a specificity of 26.1% to correctly discard doubtful P1 samples from doubtless P2 samples. These results suggest that the analysis of the presence and number of HLF by Sorensen-Dice coefficient and Jaccard index may be a good method to identify positive individuals (matches between P1 and P2), but the model has shortcomings for discarding negative individuals (no matches between P1 and P2). To increase the probability of individual identification, visual inspection of doubtful and doubtless samples with high coincidence (selected from Table 3) was performed by two independent forensic science officers.

The inspection resulted in a total correspondence (100%) between doubtful and doubtless samples, suggesting a conclusive human identification of the individuals. These findings suggest that the morphological variability and individual pattern of HLF of dorsal PIPJs, which were analyzed by a simplified method combining quantitative (Sorensen-Dice coefficient and Jaccard index) and qualitative (visual inspection) comparison, can be used as a reliable tool to facilitate human identification in forensic medicine. This is because the HLFs of the dorsal PIPJs of the fingers of every individual represent a “unique” anatomical feature of the dorsum of the hands that can be used to differentiate them from others.21 If forensic experts can accurately identify and analyze these patterns, it may help in confirming or ruling out the identity of a person in question. However, due to the small sample size, caution is advised in this interpretation, and additional research is necessary.

Current forensic medicine relies on a variety of techniques and methods to identify a person, including dental records, DNA analysis, and fingerprints, among others.14,18,19 The individual pattern of the HLF can provide additional information that supplement these other methods of identification. However, the use of dorsal PIPJ folds as a reliable method for human identification is still a relatively new approach that requires more research and validation before it can be used extensively in forensic investigations.15–17 In addition, further studies are needed to investigate the prevalence and distribution of the folds in different populations and to establish their variability over time.

Biometric information (e.g. fingerprints, face, eyes and hands) is potentially a better method of identity verification that requires data matching to confirm individual identity, which involves specific equipment and greater expertise to collect and process the information.22 For a biometric trait to be used to identity a person, certain reference qualities are required, such as universality (everyone possesses it), distinctiveness (not shared between individuals), permanence (remain unchanged over time), acceptability (by the public), elusiveness (difficult to replicate) and easy to collect with low error rates.23,24 In this regard, general public is more comfortable having their hands for identification purposes, highlighting the criteria of acceptability and easy to collect.

The human hand as an individual identifier has been used for a long time, initially by measuring hand geometry.25 Additional features of the human hand, such as fingerprints, epidermal ridges and vein patterns, have been extensively investigated and analyzed for identification purposes.26 Fingerprints are one of the most widely used biometric traits for human identification. Variability of epidermal ridges is not only determined by genetic factors, as interactions with intrauterine environment also influence the developing dermis. In addition to distinctiveness, fingerprints also match the criteria of permanence and resilience, since the epidermal ridge pattern does not change over time as a result of the resistance of the dermis to damage.27 However, several concerns related to identical patterns of epidermal ridges that, according to statistical predictions, two individuals may possess the same fingerprint as one in 64 billion, have yet to be addressed.15,28 Hand geometry (finger thickness and width, palm size, among others) and venous patterns are currently used to differentiate individuals.29,30 Information obtained from the analysis of hand geometry and venous patterns is easy to collect using specific (e.g. infrared) cameras and tracing, coding and overlay techniques that require a less invasive and more publicly acceptable method. However, hand geometry analysis provides high rates of false acceptance and rejection, resulting in a method with poor admissibility. On the other hand, an advantage of venous patterns is that they cannot be easily manipulated.

Increased attention has been paid to the unique patterns of knuckle crease for human identification purposes. Tracing and coding methods and systematic analysis of comparison for interpreting the features of the knuckle crease patterns result in a more repeatable approach than simple visual comparison of the traits.24,30 However, at present, these methods are complex and not entirely suited to the anatomical area of the knuckle creases. In this regard, consensus on criteria for image analysis and data acquisition and interpretation still requires additional studies focused on further evaluation of the morphological characteristics of knuckle crease and several additional considerations based on: (1) finger position, (2) quality of the images being compared, (3) morphological comparable features with evidential value, (4) similarity and difference of the features, and (5) reproducibility and probability of the features. Following these criteria would allow more accurate and repeatable methods of analysis and provide a solid framework for research in this field, necessary to consider knuckle crease patterns as reliable forensic evidence.

The present study evidenced that the presence and number of the horizontal linear folds in the dorsal PIPJs of the fingers should be considered for identification purposes because similarity persists with variation in image quality and provides sufficient information that can help to distinguish or exclude between individuals.

ConclusionThe findings of this study support the hypothesis that horizontal linear folds of the dorsal PIPJs can be used as a hand feature that can help narrow down human identification in forensic medicine.

LimitationsThe present study provides a small-scale analysis of the knuckle creases that require to be repeated on a larger sample size to ensure stability and reproducibility of the results. It is also necessary to address further research on the level of agreement between different features of knuckle creases. According to the simplified method proposed in the present study, further complexity of the fold pattern, by including additional key features, may add confusion and ambiguity to individual identification.

FundingOpen access publication funding: University of Granada / CBUA.

Availability of data and materialsThe datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAna Tellez-García: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Juan Suárez: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Leticia Rubio: Methodology. Stella Martín-de-las-Heras: Writing – review & editing. Ignacio Santos: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

None.

We would like to acknowledge the Forensic Science Police Officers of the Málaga Provincial HQ for Forensic National Police and the Preventive Medicine and Public Health Department of the Universidad de Málaga / CBUA for their technical support and statistical assistance.

Supplementary Figure 1. Images showing the two different scenarios and the three positions of the hands. A real scenario of the criminal acts of interest was simulated in scenario 1 (A, B) to obtain doubtful images. An ideal scenario (scenario 2) of optimal environmental conditions was created to obtain doubtless images (C, D). Devices used in scenario 1 (A) and scenario 2 (C) included photographic setups, laptop computers, cameras and platforms. Hand positions in extension, semi-flexion and holding a cylinder in scenario 1 (B) and scenario 2 (D) are also shown.

Supplementary Figure 2. Qualitative comparison between doubtful (P1) and doubtless (P2) images and delineation of the horizontal linear folds for quantitative analysis. Dashed blue lines highlight the horizontal linear folds on the dorsal aspect of the PIPJs in each finger of the left and right hands. P1 images represent the first set of photographs performed in scenario 1 and constitute the doubtful sample group. P2 images represent the second set of photographs performed in scenario 2 and constitute de doubtless sample group.