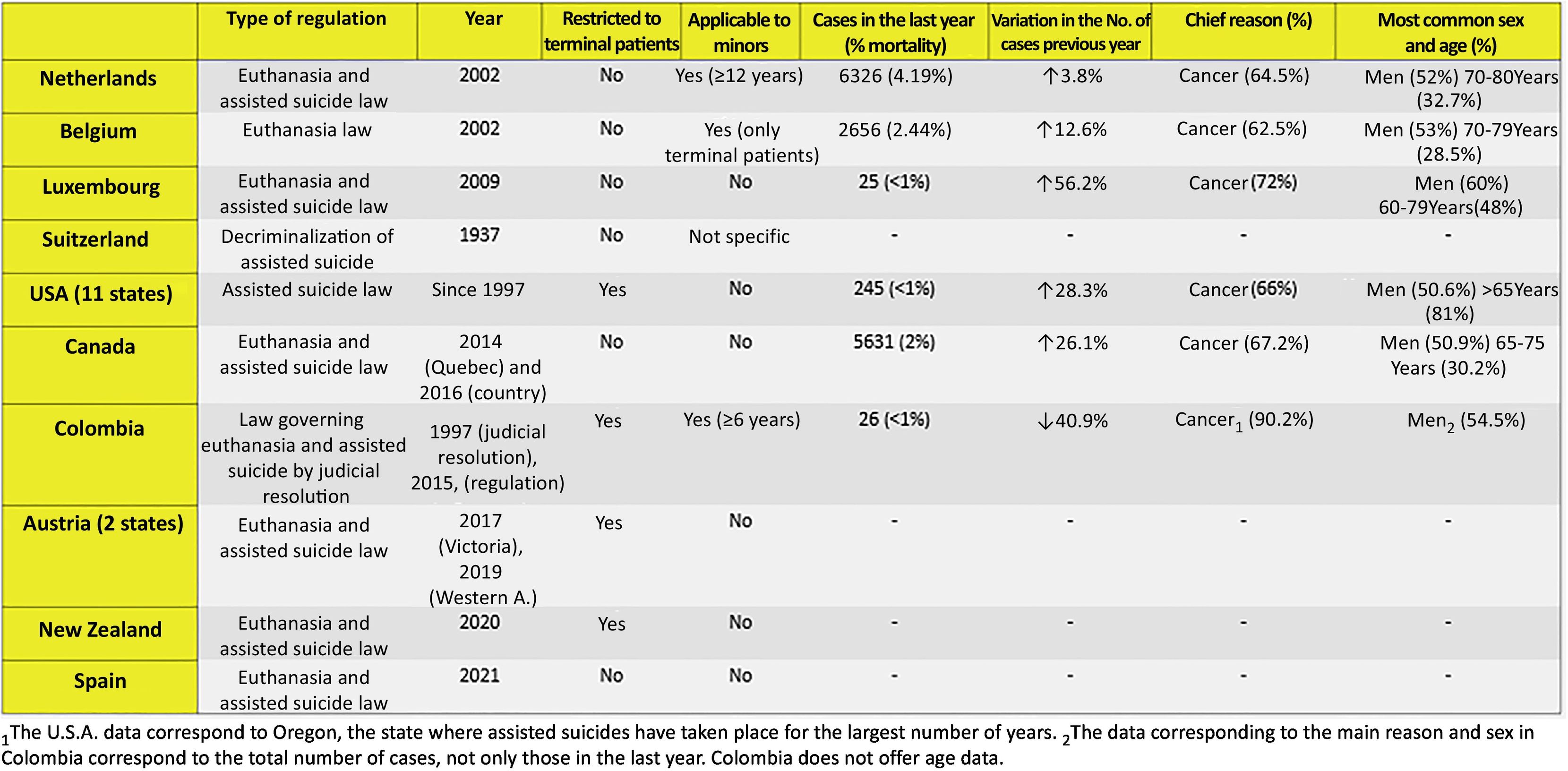

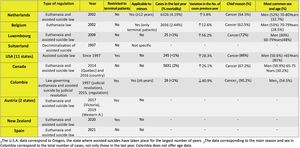

The regulation of euthanasia has been the subject of debate for years, from the fields of medicine, law, and bioethics, and therefore of legal medicine, in which these 3 disciplines converge. In the last 30 years, we have experienced a process of decriminalization and regulation in different countries of the world. Currently euthanasia and/or assisted suicide are regulated in 7 countries: the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Canada, Colombia, New Zealand, and Spain, as well as in 11 US states: Oregon, Washington, Montana, Vermont, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Maine, New Jersey, New Mexico, and the Federal District of Columbia / Washington D.C, and in 2 states of Australia: State of Victoria and Western Australia. In this review work, we carry out a study on the most important aspects of the new law of the regulation of euthanasia in Spain compared to the rest of the countries in which they also have the regularization of euthanasia and/or assisted suicide.

La regulación de la eutanasia ha sido objeto de debate desde hace años, desde los campos de la Medicina, el Derecho y la Bioética, y por tanto de la Medicina Legal, en la que estas tres disciplinas convergen. En los últimos treinta años hemos vivido un proceso de despenalización y regulación en diferentes países del mundo. Actualmente la eutanasia y/o el suicidio asistido están regulados en 7 países: Holanda, Bélgica, Luxemburgo, Canadá, Colombia, Nueva Zelanda y España, así como en 11 estados de EE. UU: Oregón, Washington, Montana, Vermont, California, Colorado, Hawái, Maine, New Jersey, New México y el Distrito Federal de Columbia / Washington D.C, y en 2 estados de Australia: Estado de Victoria y Australia Occidental. En este trabajo de revisión realizamos un estudio sobre los aspectos más importantes de la nueva ley de la regulación de la eutanasia en España comparando con el resto de los países en los que también tienen la regularización de la eutanasia y/o suicidio asistido.

As its etymology suggests, “euthanasia” comes from the Greek ey: good, and Thanatos: death, so it means a “good death” in terms of one that is free of pain and torment. Francis Bacon (1623) introduced the term into scientific vocabulary, in the sense of relieving suffering and bringing about a death that is peaceful and serene.1

The World Health Organization (the WHO) defines euthanasia as “the action of a doctor to deliberately cause the death of a patient who has an advanced or terminal illness, after the express and repeated request of the latter”.2

How to regulate euthanasia has been debated for years in the fields of medicine, law, and bioethics, as well as in legal medicine, where the 3 other disciplines converge. Several countries around the world have gone through a process of decriminalizing and regulating euthanasia in the last 30 years. Euthanasia and/or assisted suicide are currently regulated in 7 countries: the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Canada, Colombia, New Zealand, and Spain, as well as in 11 states in the U.S.A.: Oregon, Washington, Montana, Vermont, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Maine, New Jersey, New México, and the Federal District of Columbia/Washington D.C., as well as 2 states in Australia: Victoria and Western Australia.3

Important aspects of the Organic Law of the Regulation of Euthanasia in SpainWhen on June 25, 2021, Organic Law 3/2021 of the Regulation of Euthanasia in Spain (LORE) came into force, this gave rise to a major change in the exercise of the medical profession.

Euthanasia consists of the invention of a medical professional to directly and intentionally cause the death of a patient after the informed, expressed, and repeated request of the latter. This takes place within the context of suffering due to a severe and incurable disease or suffering that is chronic and disabling, and which the patient experiences as intolerable suffering that cannot be mitigated by other methods.

According to article 3. Definitions of the LORE.4

Severe and incurable disease: is one that due to its nature causes constant unbearable physical or psychological suffering without the possibility of relief that the individual would consider to be tolerable, with a restricted prognosis for survival, in a context of gradually increasing frailty. An example of this would be cancer.

Severe, chronic, and disabling suffering: this situation refers to limitations which directly affect physical independence and everyday activities, so that an individual is unable be autonomous. It also covers their ability to express themselves and communicate with others, as disability here too is associated with constant and intolerable physical and psychological suffering, when it is definite or highly probable that the said limitations will persist over time, without any possibility of a cure or appreciable improvement. This may sometimes involve complete dependency on technological support. Examples of this could be long-term progressive limitation due to COPD or Ictus, or prolonged deterioration such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, or muscular dystrophy.

As we have seen, the LORE broadens the provision of assisting patients to die (PAPD) to include other types of severe, chronic, and disabling suffering, not only those with a severe incurable disease as occurs in other countries, such as certain states in the U.S.A., Colombia, and Australia.

Other important definitions of the LORE2,4 are:

The responsible doctor: a doctor who is in charge of coordinating all of the information and medical care for the patient, and who is the main interlocutor with the same in all matters relating to their attention and information during the care process, without prejudice to the duties of other professionals taking part in care. The responsible doctor may be any medical professional, such as the family doctor or another trusted specialist doctor such as an internal medicine specialist.

Consultant: a doctor with training in the field of the diseases of the patient and who does not belong to the same team as the responsible doctor. They may be a doctor with training in the patient’s disease or a specialist in the same, such as an oncologist, a neurologist, a geriatrician, an internal medicine specialist, a GP, or a family doctor.

R The 2 forms that the PAPD4 may take would be:

1) The direct administration to the patient of a substance by the competent medical professional (euthanasia).

2) The prescription or supply to the patient by a medical professional of a substance so that it can be self-administered by the patient to bring about their own death (assisted suicide).

A situation of actual disability: situation in which the patient lacks sufficient understanding or will to fully and effectively decide for themselves, regardless of whether any measures to support their exercise of legal capacity exist or have been adopted. It is the responsible doctor who has to assess their degree of disability, coordinating all of the information and care corresponding to the patient. The responsible doctor is also in charge of evaluating the situation of disability according to the protocols for action set by the Interterritorial Council of the National Health System.5

For individuals who suffer mental disorders, it is considered prudent to review previous instruction documents or living wills when they include the request for euthanasia, thereby accrediting the patient’s capacity for informed consent.6 As the criteria for PAPD (Table 1) state, this is the only exception in individuals with actual disability. PAPD can only be implemented in this case if the individual had previously prepared an instruction accrediting their desire or will respecting the request for euthanasia.

Requisites for the provision of assistance to die.

| • Spanish nationality, legal residence in Spain, or a certificate of registration that accredits a time spent in Spanish territory of longer than 12 months, being of age and capable and conscious. |

| • Holding information in writing on their medical process, the alternatives including palliative care and the provisions to which they have a right, according to the regulations on care for dependent individuals. |

| • Having prepared 2 requests voluntarily and in writing or another medium which provides proof (when the health of the individual does not permit the patient to date and sign a document, an audio-visual format will be valid), leaving a separation of at least 15 calendar days between both requests. |

| • Having a severe and incurable disease or severe, chronic, and disabling suffering. |

| • Having given prior informed consent to PAPD, this having been included in their clinical history. |

| • Individuals in a “Situation of actual disability” only if they had previously prepared a document of instructions, a living will or the expression of anticipated wishes specifically stating their will respecting the possibility of euthanasia. |

The requirements for the PAPD are shown in Table 1.4

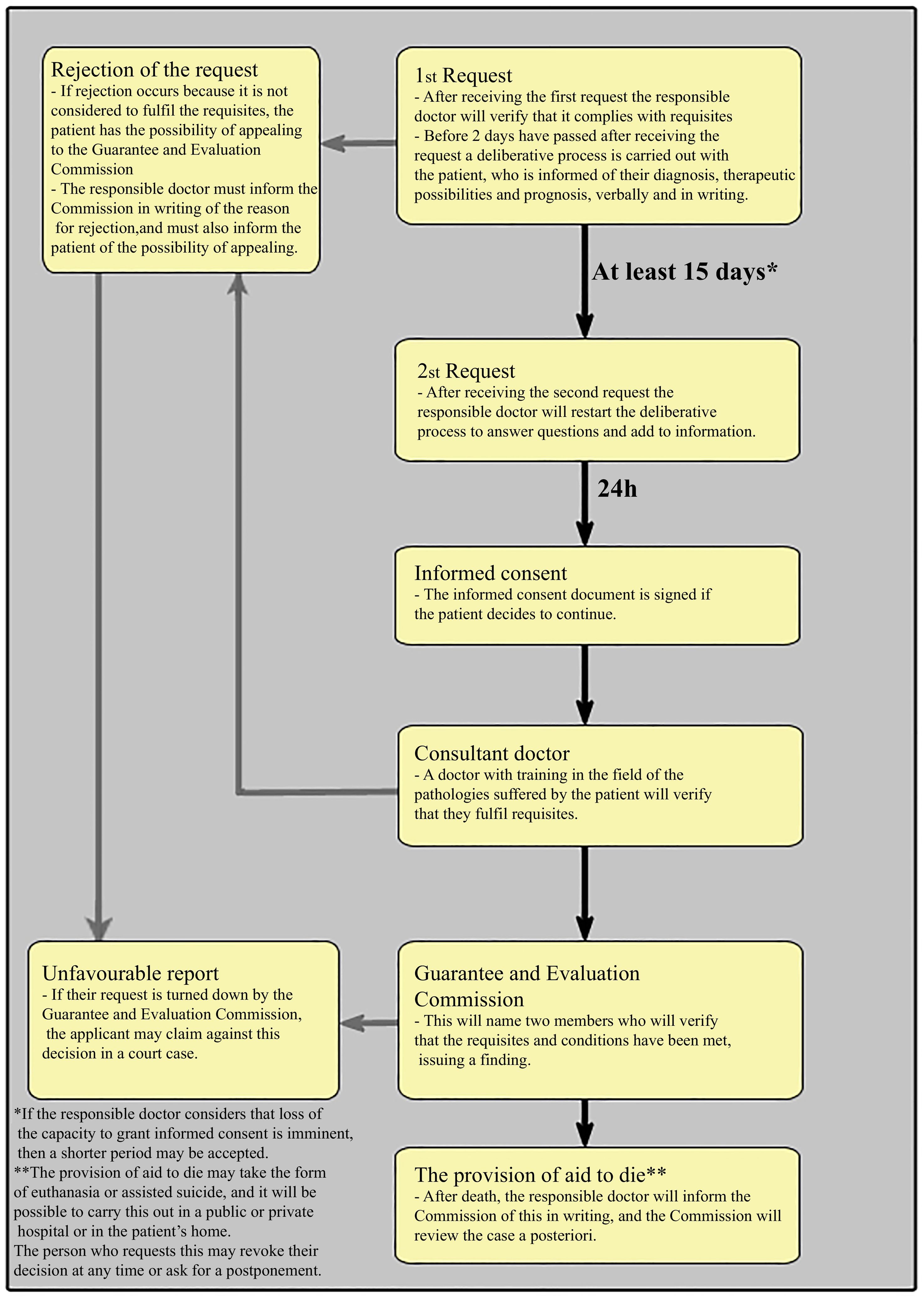

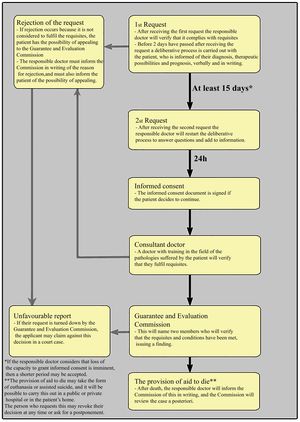

The legally regulated process may be summarized as follows (Fig. 1):

- 1)

Request for the PAPD. This is prepared in writing, or in another medium which offers proof (when the health of the patient does not permit them to sign and date a document then an audio-visual format will be valid, when the responsible doctor ratifies the veracity of the recording), signed by the patient who requests it and a doctor who may or may not be the responsible doctor of the patient. If they are not the responsible doctor then the document will be delivered to the same.

- 2)

Once the request has been received and in a maximum period of 2 days, the responsible doctor has to verify that the patient fulfils the requisites (of age, resident in Spain, capable and competent and that they suffer a severe, chronic, and disabling disease or one that is severe and incurable). At this moment, the responsible doctor will carry out a deliberative process with the patient on their diagnosis, therapeutic possibilities (including palliative care) and the results that can be expected. This information must also be supplied in writing.

- 3)

If the patient decides to continue, they have to prepare a second request at least 15 calendar days after the first one. This second request must also be in writing or another medium that offers proof (when the patient’s health does not permit them to sign and date a document then an audio-visual format will be valid, and the responsible doctor is to ratify the veracity of the recording), usually signed by the patient and the responsible doctor, although in some cases the request may also be signed by another medical professional, who is always to ensure that the request is delivered to the responsible doctor.

- 4)

After receiving the second request, the responsible doctor will repeat the deliberative process in a maximum of 2 days, to resolve any doubts or any need for additional information.

- 5)

24 hours after the end of the previous deliberative process, the responsible doctor will ask the requesting patient whether they wish to continue or not. If affirmative, they will at this moment sign the informed consent. The medical team and family members will also be informed at this time, if the patient so requests.

- 6)

At this time, the responsible doctor must request the opinion of a consultant doctor. This consultant must be a doctor with training in the field of the diseases suffered by the patient and also unconnected with the team of the responsible doctor. Their function consists of preparing a report on compliance with the requisites, and informing the patient of the conclusions.

- 7)

With the favorable report of the consultant, the responsible doctor will inform the Guarantee and Evaluation Commission of the case. The Commission will designate 2 of its members, a doctor and a jurist, to verify compliance with the requisites and the conditions.

- 8)

The commission will inform the responsible doctor of the definitive decision, which if favorable, will permit implementation of the PAPD. If the patient decides to self-administer the medication that will end their life, the care team will maintain the due task of observation and support until the moment of death.

- 9)

After the death of the patient, the responsible doctor will issue 2 documents for the Guarantee and Evaluation Commission on the procedure followed, so that the Commission is able to carry out an a posteriori review.

Another important aspect of the LORE4 is the right to conscientious objection by the professionals directly involved in the PAPD, as article 3 of the said law states: “Medical conscientious objection”: the individual right of medical professionals not to treat when demands for medical actions regulated by this law are incompatible with their own convictions and in article 16.

Conscientious objection by medical professionalsThe medical professionals who are directly involved in the provision of assisted death are free to exercise their right to conscientious objection.

Rejecting or refusing to provide such services due to reasons of conscience is an individual decision taken by medical professionals who are directly involved in the same, and they should express this beforehand and in writing.

Medical administrative bodies will create a register of medical workers who as conscientious objectors will not take part in assisted deaths. This registry will list the declarations of conscientious objection against taking part in the same, and it has the purpose of facilitating the necessary information for the medical administration, so that it is able to guarantee suitable management of the PAPD.

Table 2 shows a list of the medical professionals who are directly involved in the PAPD and who may exercise their right to conscientious objection according to article 16.1 of the LORE. They are the ones who perform the necessary or simultaneous actions without which it would not be possible to carry it out.5

List of the medical professionals who may exercise their right to conscientious objection.

| • The responsible doctor |

| • Consultant doctor |

| • Medical and nursing professionals who take part in the PAPD |

| • Other medical and nursing professionals who take part in the PAPD, such as psychiatrists and clinical psychologists |

| • Pharmacists, if it is necessary to prepare special formulas or kits of medicines for the PAPD |

To summarize, we can conclude that the LORE follows the Anglo-Saxon model, which is based on the law in the state of Oregon (the first U.S.A. state to legalize assisted suicide, in 1997) as well as the Canadian law. The Spanish law is very strict, with highly specific requisites and time limits that have to be met. These are described in all of the model documents that have to be filled out in the “Manual of good practices in euthanasia” published by the Ministry of Health.6 The time limits and process flow diagrams that have to be fulfilled for the PAPD are described in great detail in the “Right to euthanasia. Guide to the general process and time limits for the PAPD”, which is published by the management of the Board of Health of the Autonomous Government of Castile and León.7

It is important to take into account that Colombia and Spain are the only 2 countries where to carry out the PAPD, a favorable previous report is required from the Guarantees and Evaluation Commission of each Autonomous Community. Nevertheless, in the Netherlands and Belgium the Regional Commissions act after the implementation of an assisted death.

Countries in which the practice of euthanasia and/or assisted suicide is regulatedThe NetherlandsThe Netherlands became the first country in the world to have a law which regulated euthanasia and assisted suicide in April 2002, through Law 26691/2001, the “Law governing the termination of life at the request of the individual and for assisted suicide”.

The Dutch law permits the use of assistance to die for minors above the age of 12 years, on condition that they are considered to be capable of reasonably evaluating their own interests and when 1 parent agrees with the decision. From 16 to 18 years old, the parents only take part in the decision-making process.

One of the most controversial aspects of the Dutch law, apart from the fact that it covers minors, is that it permits euthanasia in patients whose cause of suffering is solely or mainly a psychiatric disorder,8 as this is expressly prohibited in other countries.

The RTE (Regionale Toetsingscommissies Euthanasie) are the Regional Commissions for Reviewing Euthanasia. They have the task of reviewing each case of euthanasia or assisted suicide that has been carried out to verify a posteriori that the criteria were fulfilled. They also issue an annual report containing the data corresponding to completed euthanasia and assisted suicide cases.

The Dutch and Belgian Regional Commissions act after the practice of assisted dying has taken place. However, in Colombia and Spain a favorable report by a doctor and jurist who are members of the Guarantees and Evaluation Commission in each Community is indispensable beforehand for the PAPD.

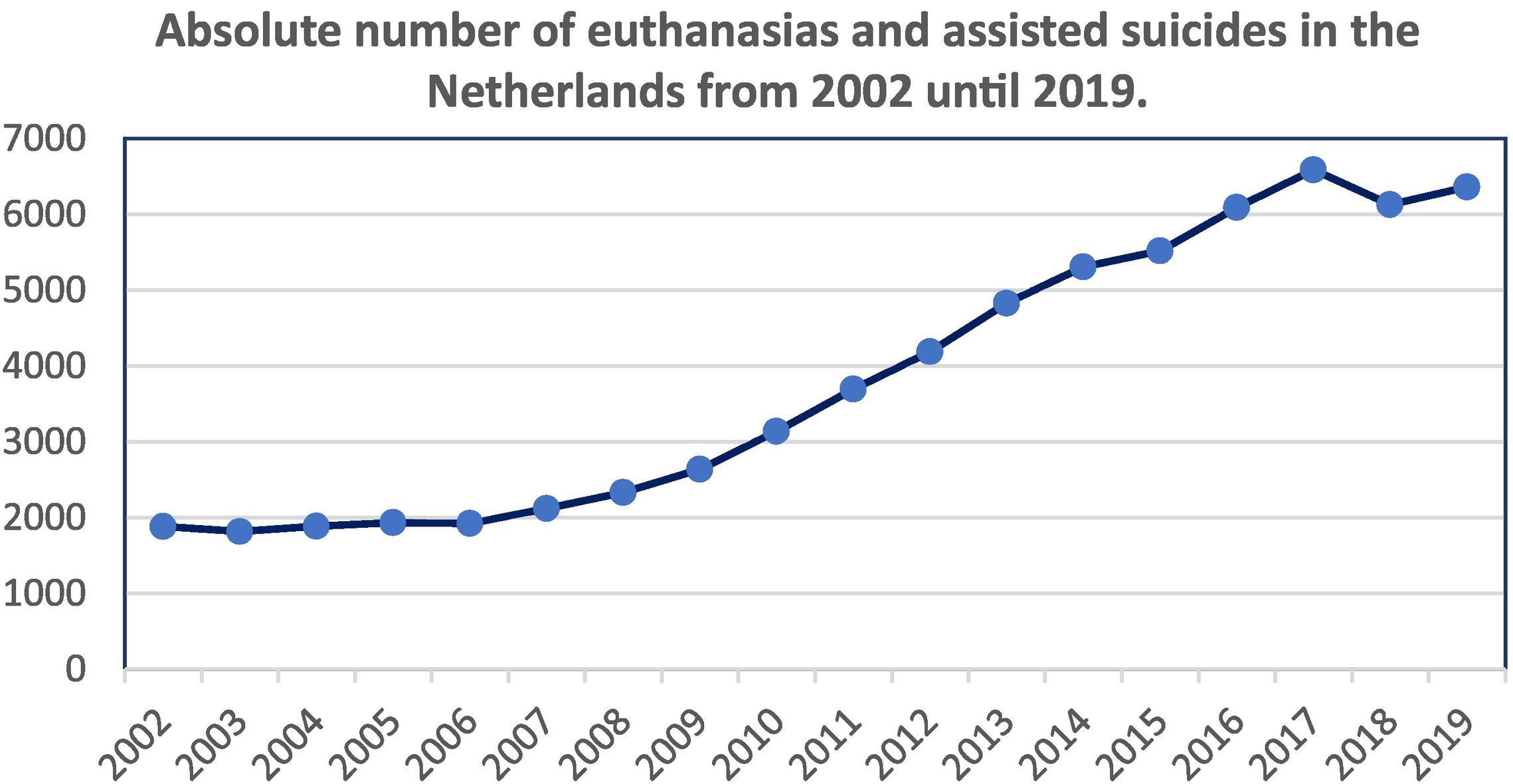

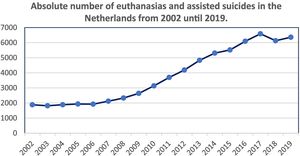

Fig. 2 shows that since 2002, a total of 1882 euthanasias have been carried out. The tendency has been for them to increase in number, with a small reduction in the number of cases of euthanasia and assisted suicide that were practiced.9

Data obtained from the Annual Reports published by the Regional Commissions for the Review of Euthanasia (RTE).9

In every year, cancer is the disease which caused the largest number of requests,10 followed by nervous system, cardiovascular, and lung diseases, in this order. Provisions for patients with mental illnesses and dementia accounted for a small percentage of the total (3.02% for dementia and 1.07% for mental illness in 2019), although this have gradually increased: in 2010, the percentage was 0.80% for dementia and 0.06% for mental illness. Cases involving minors appear very occasionally: 9 cases in the last 6 years, and no case in 2019.

BelgiumIn May 2002, Belgium passed a law which regulated euthanasia but not assisted suicide.

The great peculiarity of the Belgian law is that following the modification of February 28, 2014 euthanasia can be applied to any minor, on condition that they are able to discern and are conscious at the moment they make the request. A minor must be in a terminal situation and the parents must agree if they are to receive euthanasia. Belgium is currently the only country with no age limit for euthanasia, and with the Netherlands and Colombia they are the only countries that allow euthanasia in minors.11

There is a Federal Commission for Control and Evaluation which reviews each report issued after a case of euthanasia. This commission prepares a biannual data report.12

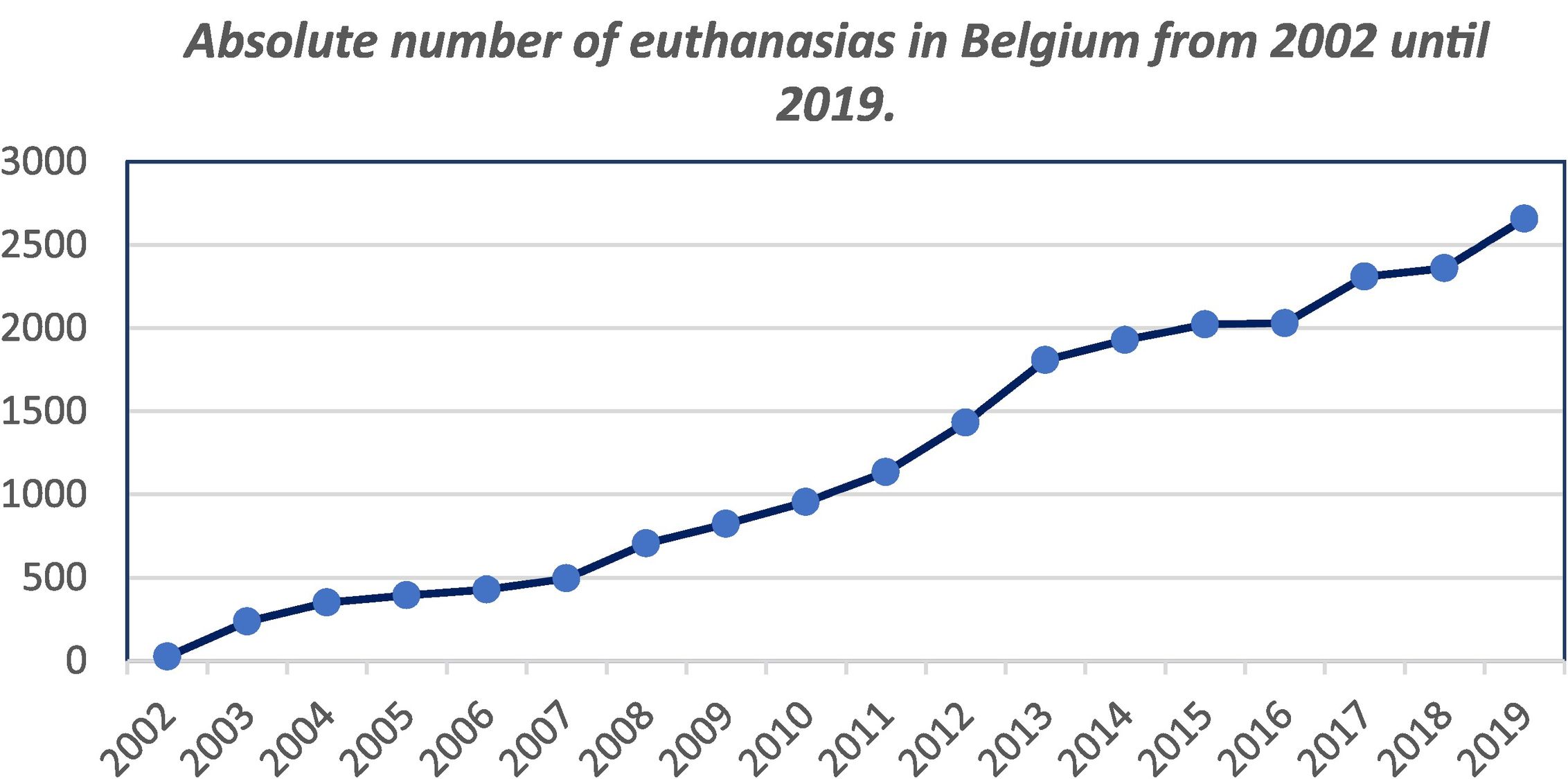

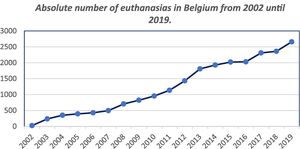

As can be seen in Fig. 3, the number of euthanasias practiced in Belgium since 2002 has grown considerably, from 24 euthanasias in 2002 up to 2656 euthanasias in the last year. Cancer was the disease mentioned the most often as the cause, although as was the case in the Netherlands, the corresponding proportion of cases has gradually fallen, from 195 cases (82.98% of the total) in 2003 to 1659 (62.46% of the total) in 2019. The next most common reasons are multiple pathologies, nervous system, cardiovascular, and lung diseases, in that order. Psychiatric reasons (including dementia) are rare, with 49 cases (1.84% of the total) in 2019. Euthanasia in minors is exceptional, with 4 cases since it was legalized, one of which occurred in 2019.

Data obtained from the Euthanasia Reports (“Rapport Euthanasie”) published by the Commission fédérale de contrôle et d'évaluation de l'euthanasie.12

Euthanasia together with assisted suicide were legalized here in 2009 following the Dutch and Belgian model: the patient has to be in a situation of irreversible physical or psychological suffering, the request has to be voluntary, considered, and repeated (although specific periods of time are not specified). There can be no other reasonable alternative for the patient’s situation, and the requisites have to be verified by an independent consultant doctor. It also covers euthanasia and assisted suicide when patients have recorded their desires in a living will or equivalent document. Unlike the Dutch or Belgian laws, it does not include any conditions under which it could be applied to minors.

SwitzerlandThe Swiss Penal Code clearly prohibits euthanasia, although it penalizes it less strongly than involuntary homicide, and it solely condemns assisted suicide if it is motivated by selfish ends.

This lack of legislation for unselfish assisted suicide makes Swiss law on this point quite different from the law in other countries:

- •

It can be applied to anyone, and there is no need to comply with medical requisites.

- •

It can be applied by anyone. These 2 points mean that assisted suicide is excluded from medical interventions.

- •

Organizations have been set up for assisted suicide. The best-known of these are Exit, which assists Swiss citizens to commit suicide, and Dignitas, whose clients are citizens of other countries where euthanasia and assisted suicide are regarded as crimes.

- •

There are no official data on assisted suicides, as they are simply counted as suicides. The available data are those offered by the aforesaid organizations.

Since 1997, 10 states and 1 federal district have approved assisted suicide within the context of a plan for end-of-life care: Oregon (1997), Washington (2009), Montana (2009), Vermont (2013), California (2016), Colorado (2016), Hawaii (2019), Maine (2019), New Jersey (2019), New México (2021), and the Federal District of Columbia/Washington D.C. (2017).

Assisted suicide is restricted by the law to patients above 18 years old with a life expectancy of less than 6 months and suffering that cannot be relieved. Assisted suicide for non-terminal patients is illegal in all states.

The last 2020 report from Oregon state clearly shows a growing tendency for medically assisted suicides, up from 16 cases in 1998 to 245 in 2020. The average age was 74 years (81% above 65 years), with slightly more men (50.6%, although this percentage reached 59.7% in 2019). Cancer was the main medical condition (66%), although this percentage had fallen in comparison with previous years, when it reached 70%–85%.13

CanadaThe province of Quebec legalized euthanasia in 2014 within a law governing end-of-life care. Subsequently in 2016 and by order of the Supreme Court, euthanasia and assisted suicide were legalized in the whole country.14 The patient must be older than 18 years and suffer a severe and irreversible disease which causes an advanced state of dependency and physical or psychological suffering that cannot be relieved under conditions they consider to be acceptable. Assistance to die is not restricted to terminal patients. It also specifies that patients whose medical condition is solely mental cannot yet be offered assistance to die.

The last annual report issued by Canada, in 2019, contains data very similar to those of the Netherlands and Belgium. On the one hand, the number of euthanasias has gradually increased, up to 5631 in 2019, a 26.1% increase over 2018. The average age is 75.2 years, with very slight differences between the sexes (50.9% men and 49.1% women). Cancer was the medical condition mentioned the most often, at 67.2% of cases.

ColombiaColombia is the only Latin American country in which euthanasia and/or assisted suicide are permitted. Euthanasia was first practiced there in 2015. It can only be used for adults and since then has been used for 40 patients.

It establishes particular conditions for different age ranges, always with the criterion that the disease is terminal and suffering is constant, unbearable, and impossible to relieve. The other requisite is that consent must be free, informed, and unequivocal. Both criteria have to be assessed by a doctor as well as by an Interdisciplinary Scientific Committee. Colombia was therefore the first country in which previous assessment by a committee was required. Like the current Spanish law, a favorable report is also necessary beforehand from the Guarantees and Evaluation Commission.

Minors under the age of 6 years are excluded, as are individuals with mental disabilities or psychiatric disorders. It may only be applied in exceptional cases for individuals aged from 6 to 12 years, although parental authorization is obligatory. Although the autonomy of the minor prevails from 12 to 14 years old, the parents also have to agree. And above 14 years only, the will of the adolescent counts.

AustraliaAlthough it has been said that the Netherlands was the first country to legalize euthanasia, this is not entirely true. The Northern Territory state in Australia passed a law that came into force on July 1, 1996 but did not last for a year. 7 patients requested euthanasia during this time, and it was completed in 4 of them.

The state of Victoria has a law governing assisted death, and this came into force in June 2019. This is one of the most extensive laws, and it regulates assisted suicide and euthanasia in terminal patients.

In 2018, the state of Western Australia passed a law on assisted death that is very similar to the one in Victoria. The main difference is that it considers euthanasia and assisted suicide to be on the same level.

GermanyThe German Penal Code (Strafgesetzbuch) in §216 includes homicide on demand as a crime punishable with a prison term of from 6 months to 5 years. §217 states that assisting suicide with a repetitive intention is punishable with up to 3 years in prison or a fine. Nevertheless, point 2 excludes those who have no intention to repeat, regardless of whether they are a family member or somebody close.15

The German Penal Code therefore seeks to decriminalize sporadic assisted suicide when it is undertaken in a single instance by family members. This place assisted suicide outside the medical context, and it prohibits the existence of private companies which work by assisting death. On February 26, 2020, the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany nullified the said article 217, opening up the possibility of a broader regulation to govern assisted suicide.

New ZealandIn October 2020, New Zealand passed its End of Life Choice Law. This law governs euthanasia as well as assisted suicide in terminal patients who are of age, with physical or psychological suffering that cannot be relieved under conditions they consider to be acceptable. This law came into force on November 6, 2021.

Other countriesIn many countries, there is still intense debate at the ethical as well as the legal level.16

Portugal is an example of this. In January 2021, its parliament passed a law decriminalizing euthanasia under certain circumstances that were not restricted to terminal patients, although this law was revoked by the Constitutional Court before it came into force.

On November 5, 2021, parliament passed the regulation decriminalizing euthanasia once again. However, the law was finally vetoed by the Portuguese President, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa.

The United Kingdom founded the palliative care philosophy of “care not killing”. Although it is one of the firmest opponents of assisted suicide,1 multiple proposals for the legalization of assisted suicide have been made, the last of which was created in 2019 and is still awaiting its second reading the House of Lords.

In France, a law of March 2015 permits the “deep and continuous” sedation of terminal patients and governs living wills, although it favors “palliative care”. Euthanasia is legally classified as premeditated murder or poisoning, and it is punishable with a life sentence. In March 2021, the Senate rejected a law to regulate euthanasia.

In Italy, the Living Will Law states that the patient’s decisions on the end of life are not binding, and that the doctor has the last word here. The text prohibits euthanasia, which it considers to be synonymous with voluntary homicide, as well as assisted suicide. In 2019, the Constitutional Court ruled that certain circumstances exist under which euthanasia should not be punished.3

Fig. 4 shows the laws existing in the above states and countries.

We believe that prior to request the provision of euthanasia or medically assisted suicide, or PAPD, in all countries, it would be very important to also develop suitable plans for palliative care, as an alternative to be able to help terminal patients to live the time remaining to them without physical or psychological suffering, as it is not easy to determine whether a patient wishes to die or wishes to cease to suffer. Palliative care is a form of care that the aim of ensuring well-being, comfort, and the best quality of life.17 This was done in countries such as Belgium and Luxembourg, which simultaneously passed the Law Governing Euthanasia and the Law of Palliative Care, as an alternative.

FinancingThis study received no specific grant from public, private or not-for-profit sector bodies.

Please cite this article as: Martínez-León M, Feijoo Velaz J, Queipo Burón D, Martínez-León C. Estudio médico legal de la Ley Orgánica de Regulación de la Eutanasia en España en comparación con el resto de los países que regulan la eutanasia y/o el suicidio asistido. Revista Española de Medicina Legal. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reml.2022.01.003