Conventional care models for older adults often disregard negative effects of hospitalization and neglect potential benefits of technology. This trial aims to investigate effects of Multicomponent Exercise Program with Virtual Reality (MEP-VR) on functional and cognitive outcomes in hospitalized older adults, compared to MEP-only or usual care approaches.

MethodsThis three-arm, parallel-group, randomized controlled trial will include 255 participants aged 75 or older, with a Barthel Index score of at least 60, able to walk and cooperate, have an estimated hospital stay of at least four days, and provide informed consent. Patients with severe dementia, terminal illness, or clinical instability will be excluded. Participants will be randomly assigned to a control group or one of two intervention groups. The intervention groups will receive either MEP-VR or MEP-only program, consisting of supervised aerobic exercise, resistance training, and balance training, with or without a virtual reality component. The intervention will occur over four consecutive days, each session lasting 30–40min. The primary outcome measure will be functional changes at discharge. Cognition, mood, quality of life, and immersive virtual reality (IVR) usability will also be assessed.

DiscussionTechnological advances are rapidly increasing with population aging, creating potential benefits for integrating technology into older adult care. This study will evaluate the implementation of IVR combined with MEP. If our hypothesis proves accurate, it will pave the way for modifying the hospitalization system, helping to reduce the critical healthcare burden resulting from hospital-acquired disability in the older population.

Trial registrationThis study was approved by the Navarra Clinical Research Ethics Committee on June 14th, 2021 (PI_2021_90). The trial was retrospectively registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, registration number NCT06469554.

Los modelos de atención convencionales para los adultos mayores a menudo ignoran los efectos negativos de la hospitalización y descuidan los beneficios potenciales de la tecnología. Este ensayo tiene como objetivo investigar los efectos del Programa de Ejercicio Multicomponente con Realidad Virtual (MEP-VR) sobre los resultados funcionales y cognitivos en adultos mayores hospitalizados, en comparación con el MEP solo o con los enfoques de atención habituales.

MétodosEste ensayo controlado aleatorizado de grupos paralelos de tres brazos incluirá 255 participantes de 75 años o más, con una puntuación del índice de Barthel de al menos 60, capaces de caminar y cooperar, con una estancia hospitalaria estimada de al menos cuatro días y que proporcionen consentimiento informado. Se excluirá a los pacientes con demencia grave, enfermedad terminal o inestabilidad clínica. Los participantes serán asignados aleatoriamente a un grupo de control o a uno de los dos grupos de intervención. Los grupos de intervención recibirán un programa MEP-VR o solo MEP, consistente en ejercicio aeróbico supervisado, entrenamiento de resistencia y entrenamiento del equilibrio, con o sin un componente de realidad virtual. La intervención tendrá lugar durante cuatro días consecutivos y cada sesión durará entre 30 y 40minutos. La medida de resultado primaria serán los cambios funcionales en el momento del alta. También se evaluarán la cognición, el estado de ánimo, la calidad de vida y la usabilidad de la realidad virtual inmersiva (RVI).

DiscusiónLos avances tecnológicos están aumentando rápidamente con el envejecimiento de la población, creando beneficios potenciales para la integración de la tecnología en el cuidado de adultos mayores. Este estudio evalúa la implementación de RVI combinada con MEP. Si nuestra hipótesis resulta acertada, allanará el camino para modificar el sistema de hospitalización, ayudando a reducir la carga crítica para la atención sanitaria que supone la discapacidad adquirida en el hospital en la población de edad avanzada.

Registro del ensayoEste estudio fue aprobado por el Comité Ético de Investigación Clínica de Navarra el 14 de junio de 2021 (PI_2021_90). El ensayo se registró de forma retrospectiva en ClinicalTrials.gov, número de registro NCT06469554.

Acute hospitalization is a critical component of the healthcare pathway in the older population, which often results in functional impairment and disability as side effects.1–5 A reduction in physiological resources increases the likelihood of unfavorable consequences linked to bed rest, such as functional and cognitive decline, lengthened hospital stay, and elevated rates of mortality and institutionalization.1,6–10 Functional decline affects approximately 30–50% of hospitalized older individuals, and a lower level of function at discharge confers an increased risk of dying or worsening function the year after discharge.3,11–13

Conventional care models for older adults tend to disregard the negative effects of hospitalization and neglect the potential benefits of technology to address these issues. According to recent studies, physical exercise and early rehabilitation programs have been found to be beneficial in preventing functional and cognitive decline during hospitalization and in reducing hospital stay and mortality rates.6,12,14–17 Although interventions that focus solely on promoting mobility through Multicomponent Exercise Programs (MEP) have shown benefits, MEP with Virtual Reality (MEP-VR) (i.e., combining muscle-strengthening tasks, aerobic and balance training with the use of virtual reality tools) may provide additional benefits in terms of physical and cognitive performance in hospitalised patients.

Virtual reality (VR) is an emerging tool that can be useful for promoting and engaging older adults in physical and cognitive activities. According to the degree of immersion, non-immersive, semi-immersive, and fully immersive systems, such as head-mounted displays (HMD), can be used. Immersive Virtual Reality (IVR) transports users into an environment in which they are encouraged to execute other activities and stimulate cognitive skills. VR has numerous benefits and is considered an affordable, novel, and safe tool.18–22 Despite these promising results, further research is required to understand the benefits and limitations of VR in older adults.

The main aim of this study is to investigate the effects of MEP-VR on functional and cognitive outcomes in hospitalized older adults compared to standard care approaches. The effects on mood, safety, and usability will also be assessed. Our hypothesis is that MEP-VR can be associated with improved functional and cognitive abilities at discharge.

MethodsStudy designThis study will be a three-arm randomized clinical trial with a parallel group of 1:1:1 allocation (two experimental intervention groups and a control group). It will be conducted in the Acute Geriatric Unit (AGU) department of the Hospital Universitario de Navarra (Pamplona, Spain). The AGU department has 45 allocated beds and is staffed by 15 geriatricians working in the unit. Patients are primarily admitted to the AGU from the Emergency Department, with heart failure and pulmonary and infectious diseases as the main causes of admission.

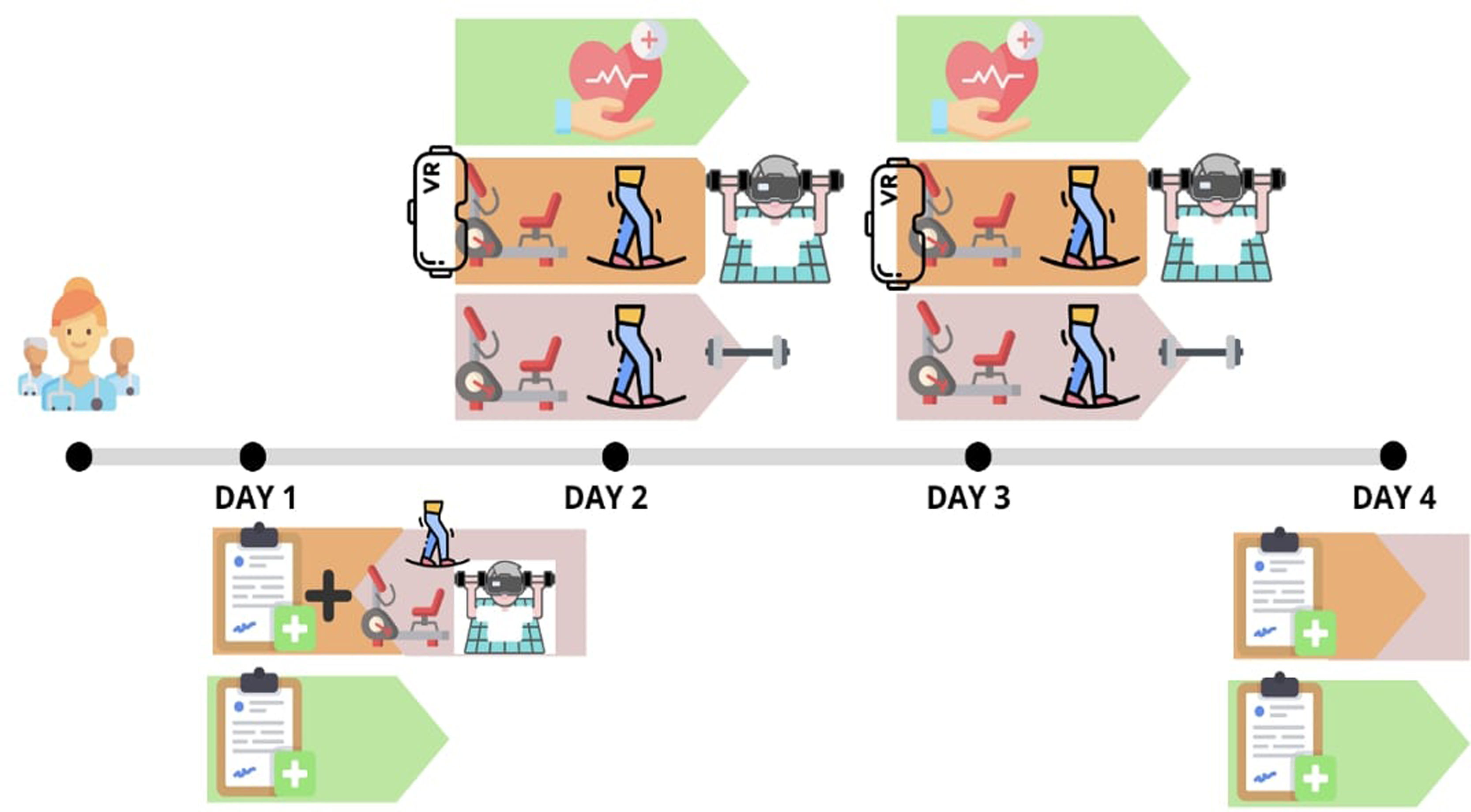

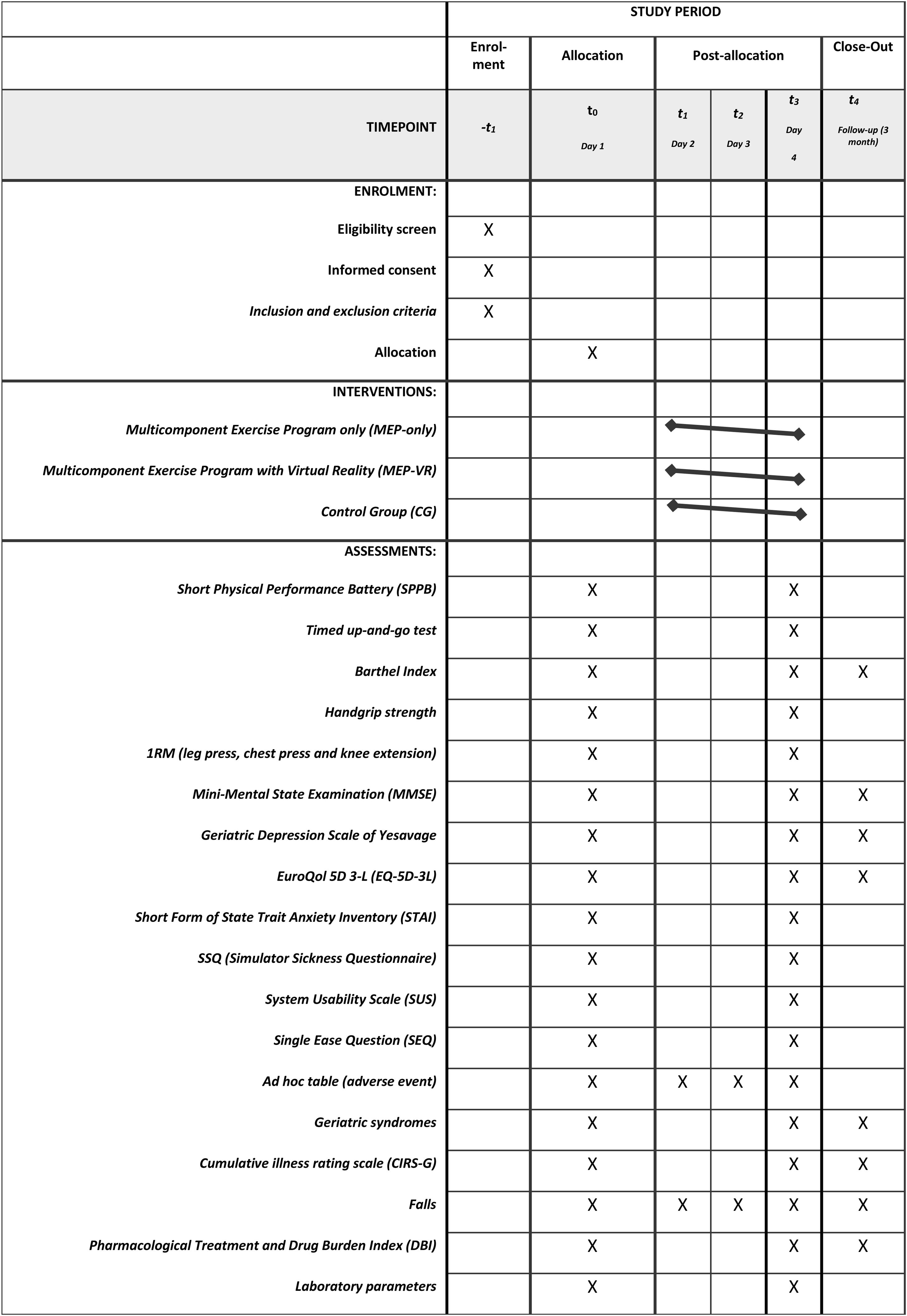

The study will be conducted in accordance with the principles of randomization and blinding. Eligible patients will be randomly assigned to one of the three groups: MEP-only, MEP-VR, control group (usual care). The researcher responsible for assigning patients to a group will not be the attending geriatrician. Before randomization, the attending geriatrician will assess the absolute and relative contraindications to participation in the program and provide general information regarding the study. Patients or their caregivers/legal guardians will be informed of their random inclusion in one group but not the group to which they belong. The staff involved in the training intervention will not be blinded to the group assignments; however, the staff involved in the assessment will not be aware of this information. After screening, patients who fulfill the eligibility criteria will be randomly assigned to one of the groups (MEP-only, MEP-VR or control) in a 1:1:1 ratio, using random permuted block design with random block sizes of 6 or 9, generated by the randomizer package in R. Participants will be explicitly informed and reminded not to discuss their randomization assignment with the assessment staff. The assessment staff will be blinded to the participants’ group and the main study design. It is not possible to mask the group assignment to the staff involved in the IG training. Patients and caregivers/legal guardians (in case the patient has cognitive impairment) will be informed of their random inclusion in one group but will not be informed on the group in which they are. The participants, legal tutor, or their acquaintances will provide their written informed consent to participate in this study. Data for the intervention and control groups will be collected at three different time points: at the start of the intervention during acute hospitalization (on the first day of the study), at the end of the intervention (on the last day of the study), and three months after discharge through a follow-up outpatient visit. The times at which different variables will be measured are listed in Table 1.

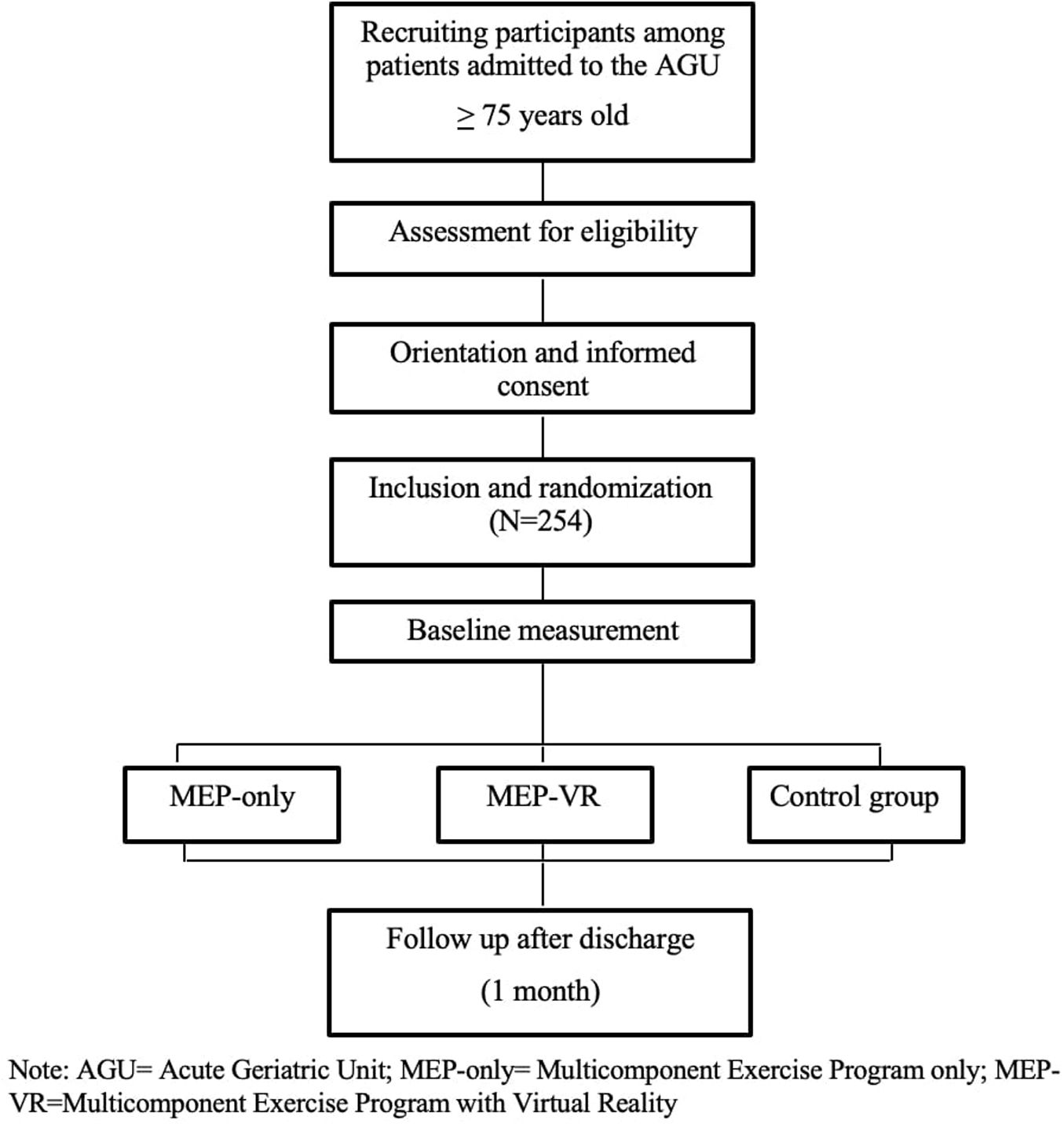

The multidisciplinary research team will include a physiotherapist, nurse, sports science specialist, and geriatrician who will perform the measurements and evaluations. Basic sociodemographic data of the participants will be collected at baseline. Adverse events will be recorded during the intervention period, as well as the eventual dropouts. The flow diagram of this study is shown in Fig. 1, and a schematic timeline of the study is presented in Fig. 2.

Plans to promote participant retention and complete follow-up include email or text message reminders about appointments, participant empowerment, and resource facilitation. As for the data monitoring, a formal committee is not requested due to the type of study.

The protocol was approved by the Navarra Clinical Research Ethics Committee (PI_2021_90, June 14th, 2021), incorporated standardized items for clinical trials in accordance with the SPIRIT 2013 statement23 (see checklist Additional file 1), and adhered to the guidelines outlined in the CONSORT statement.24 See Additional files 2 and 3 for the informed consent and additional information on biological samples storage.

The trial was retrospectively registered at ClinicalTrials.gov and assigned to the identifier NCT06469554.

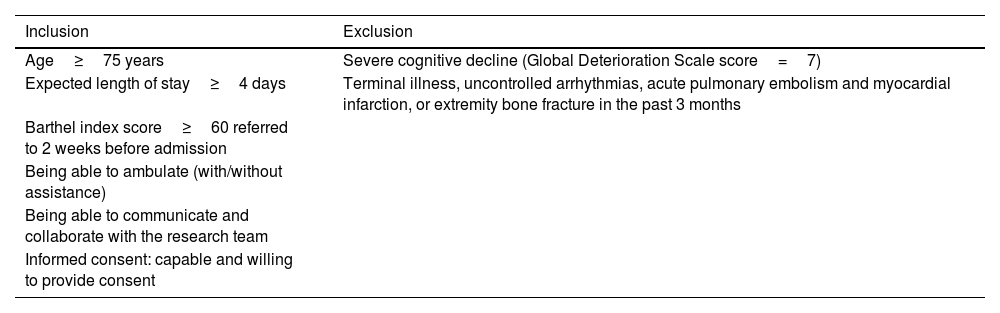

Study participants and eligibility criteriaGeriatricians at the AGU will screen all admitted patients for eligibility criteria (fully listed in Table 2) to identify participants with sufficient functional reserve and cognitive capacity to participate in the program.

Eligibility criteria.

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Age≥75 years | Severe cognitive decline (Global Deterioration Scale score=7) |

| Expected length of stay≥4 days | Terminal illness, uncontrolled arrhythmias, acute pulmonary embolism and myocardial infarction, or extremity bone fracture in the past 3 months |

| Barthel index score≥60 referred to 2 weeks before admission | |

| Being able to ambulate (with/without assistance) | |

| Being able to communicate and collaborate with the research team | |

| Informed consent: capable and willing to provide consent |

To detect a difference of 1 point in the SPPB at discharge between both intervention groups and the control group using and ANCOVA model, assuming a significance level of α=0.05 and a power of 0.2, 72 patients per group will be required. Assuming 15% losses, the target enrollment for each group is 85 patients, and consequently, a total sample size of 255 subjects.

Randomization group using mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range, whereas categorical variables will be summarized using frequencies and percentages, will describe quantitative variables. The effect of the intervention on the different outcome variables will be analyzed using ANCOVA models or linear mixed models. If any variable presented relevant baseline differences, a sensitivity analysis will be performed, adjusting for these variables. No missing data imputations are planned. The analysis follows the intention-to-treat principle, but per-protocol analysis will also be performed as a sensitivity analysis. To determine statistical significance, a level of 0.05 will be established. The data will be analyzed with SPSS 28.0 and R software v.4.4.

Completed personal data or other documents containing protected personal health information will be stored in a locked file at the principal investigator's office. The data will be entered into an electronic de-identified database authorized by a study team member and checked for completeness and accuracy. Access to data using identifiers is strictly restricted by authorized study team members and authorities. Electronic data will be securely stored on a server regulated by a local research institute (Navarrabiomed). Any identifiable data will be maintained until consent is revoked.

Intervention- 1)

MEP-only

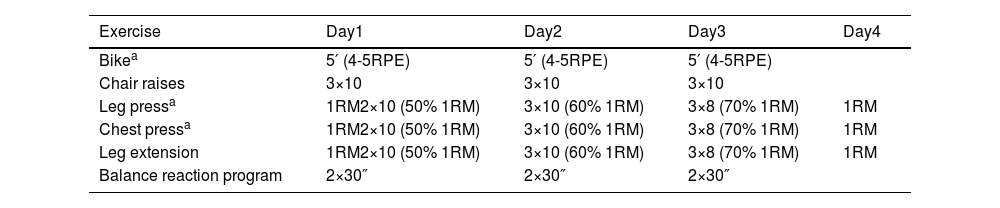

The intervention will entail the implementation of MEP training, derived from Vivifrail,25 comprising supervised aerobic training, progressive resistance/strength exercise training, and balance training, which will be conducted over a period of four consecutive days, with each session lasting approximately 30–40min (Table 3). Experienced physical trainers and physiotherapists will supervise the training sessions. The program will start with an endurance warm-up on a stationary bike (MOTOmed muvi) of an approximate duration of 7–10min, during which the individual's effort and exertion level will be measured on a 4–5 scale of the Borg Scale.26 Resistance exercises that incorporate both upper- and lower-body strengthening movements tailored to the functional capacity of each individual will be performed using weight machines such as a seated bench press, leg press, and bilateral knee extension. The participants will be instructed to perform three sets of ten repetitions of these exercises, with an intensity of 50–70% of the one-repetition maximum (1RM). The concentric phase of each movement will be performed at a velocity of 1s, whereas the eccentric phase will be performed in 3s, with a focus on controlling the motion according to the 1/3 pattern. To ensure proper execution of the exercises, the participants will be provided with instructions and will perform a specific warm-up using extremely light loads on each machine before starting the corresponding intensity level each day. The approximate duration of this training component will be 15–20min for resistance training. The concluding part of the session, lasting 10min, will be dedicated to balance training exercises. It incorporates both static and dynamic balance, as well as proprioception and reaction capacity using Lummic Light (Lummic 6 Pro). Patients will stand in the center of a virtual square with six light fixtures at three heights: three to their right and three to their left. A railing will be provided for support if necessary. With the program selected through the application, participants will be required to reach up to the light that turns on using their hands or feet, depending on the height of the light that turns on. The application will record reaction times for each session. Participants will perform two sets of 30s each day. Participants and their family members will be informed of and familiarized with the training procedures in advance.

- 2)

MEP-VR

Physical exercise scheme of intervention (MEP-only, MEP-VR).

| Exercise | Day1 | Day2 | Day3 | Day4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bikea | 5′ (4-5RPE) | 5′ (4-5RPE) | 5′ (4-5RPE) | |

| Chair raises | 3×10 | 3×10 | 3×10 | |

| Leg pressa | 1RM2×10 (50% 1RM) | 3×10 (60% 1RM) | 3×8 (70% 1RM) | 1RM |

| Chest pressa | 1RM2×10 (50% 1RM) | 3×10 (60% 1RM) | 3×8 (70% 1RM) | 1RM |

| Leg extension | 1RM2×10 (50% 1RM) | 3×10 (60% 1RM) | 3×8 (70% 1RM) | 1RM |

| Balance reaction program | 2×30″ | 2×30″ | 2×30″ |

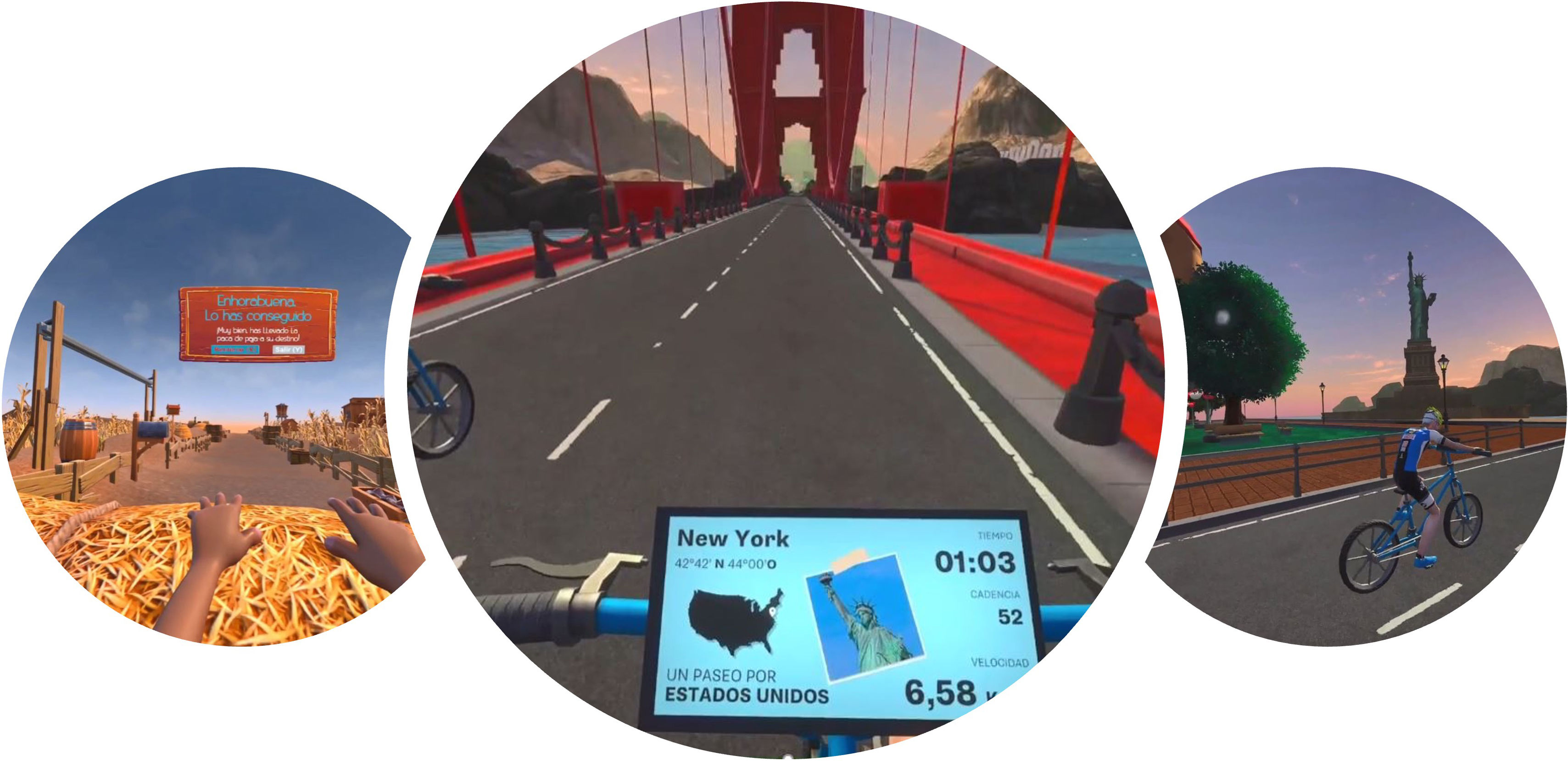

Patients randomized in this intervention group will follow an MEP identical to that of the MEP-only group (consisting of supervised aerobic training, progressive resistance/strength exercise training, and balance training) but with the added component of an IVR HMD. This program will be conducted in daily sessions lasting 30–40min for a period of four consecutive days. Before beginning the study, ad hoc software was installed in the gym room and developed for the IVR system. Checking and testing sessions were scheduled for center staff and engineers to refine and optimize the program. Two different scenarios, namely America and Europe, were created to provide an immersive and entertaining experience for the elderly participants. The entire exercise was designed with comfort and convenience in mind and the VR experience was tailored to ensure safety and prevent accidents. In addition, researchers were trained to manage technical issues that may arise from software and hardware. This group of participants will use VR during endurance bike warm-up, which will enable them to embark on a virtual world tour and on two of the three weight machines.

The project was developed using Unity and C++ as programming languages, and OpenXR technology was employed to make it compatible with various headset models, including Oculus, HP, Pico, Valve, and HTC. The scenarios were designed in Low Poly to offer a stable and fluid experience at 90fps for optimal visual comfort (Fig. 3). To ensure compatibility with the sensors attached to the exercise bike, Ant+ technology was used.

The application features two interfaces: a virtual world Canva that displays the beginning and end states of the experience, and a screen attached to the bicycle that indicates these states and provides real-time data, such as speed and cadence, travel time, and location on a map. The interface elements are large, clear, and have high contrast for easy reading. The duration of the exercise range between 5 and 7min per scenario, depending on speed and cadence. The bicycle will be equipped with two sensors, one measuring speed and the other measuring cadence, which will be connected to the software and displayed on a computer for the attendees to monitor.

To maintain patient engagement, the experience will be accompanied by a partner riding a bicycle, while providing information and interesting facts about the locations visited. The patients will also be encouraged to participate in the tour. Random background music will be played, and the sound will be ambiphonic. Additionally, particle elements and animations will be synchronized with the bicycle path to surprise and stimulate the patient (optional, as determined by the supervisor).

On the third day of training, the patient chose which of the two videos to watch. Participants’ individual effort and exertion will be measured on a 4–5 scale of the Borg Scale26 after being familiarized with the scale.

In the second half of the session, the participants will be engaged in tailored resistance training exercises targeting both their upper and lower bodies, like the intervention group MEP-only, as previously mentioned. During the seated bench press and leg press exercises, participants will also wear virtual reality glasses (projects developed using Unreal Engine 5 and Blueprint programming alongside C++). The virtual environment in which users will be situated was created using MetaXR technology compatible with Oculus Quest 2 glasses. It is a rural area featuring an avatar that executes movements typical of farm work while the participant trains on each weight machine. This design is intended to visually stimulate and motivate the participant, imparting a sense of accomplishment and challenges during the progression of the training routine. Photographs were obtained to document the environment. Virtual environments. The scenarios were designed with a Low Poly with texture resolutions no higher than 2048 or 4096 pixels, aiming for a frame rate of 90fps for optimal visual comfort. The implementation of fixed-foveated eye-tracking technology and SpaceWarp for frame interpolation was also enabled. The same Quest 2 equipment was employed along with its controls to streamline the setup process and ensure compatibility.

Usual care group (control)Subjects randomly allocated to the conventional care group will be provided with standard hospital care, which encompasses physical rehabilitation, if necessary.

Outcome measuresThe primary outcome measure of this study will be the change in functional capabilities during the study period, assessed using the following:

- -

The Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), a validated instrument for detecting frailty and predicting disability, institutionalization, and mortality, which includes tests for balance, gait, and rising from a chair, with total scores ranging from 0 (worst) to 12 (best) points.27–29

- -

The Timed Up and Go test to assess dynamic balance and the risk of falling; this test measures the time in seconds it takes for an individual to get up from a chair, walk 3m, and return to the chair. The score ranges from <10” (low falling risk), 10–20” (frailty and falling risk), and >20” (high falling risk).30

- -

The Barthel Index, an internationally recognized measure of disability, to assess functional independence on a scale ranging from 100 (autonomy) to 0 (severe functional dependence).31

- -

A handheld dynamometer (T.K.K. 5401 Grip-D, Japan) to assess isometric handgrip strength of the dominant hand. Patients will be standing with their elbow fully extended and instructed to squeeze the handle as forcefully as possible for 3s. Two valid trials will follow, and the highest value will be recorded as the data point.

- -

1RM test in bilateral leg press, knee extension, and bench press exercises using exercise machines (consecutive numbers) to assess maximal dynamic strength. Prior to the initial evaluation, the participants will engage in a warm-up regimen tailored to the exercise test. Each subject's maximal load will be precisely determined within a minimal number of attempts, with a three-minute recovery interval separating sets. Throughout all neuromuscular performance evaluations, verbal encouragement will be provided to each subject to optimize the execution of each test action. Qualified fitness specialists will individually supervise and monitor all training sessions, furnishing instructions and encouragement throughout each session.

Secondary outcomes will be:

- -

Changes in cognitive function using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), a 30-point questionnaire with a scale ranging from 0 (worst) to 30 (best).32

- -

Changes in mood status, assessed using the 15-item Yesavage Geriatric Depression Scale (Spanish version), with a scale ranging from 0 (best) to 15 (worst),33 and the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI).34

- -

Quality of life, assessed using the EuroQol-5D-5L questionnaire, which measures five dimensions of health status: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression, plus a visual analog scale (VAS) to quantify perceived health, ranging from 0 (worst health state imaginable) to 100 (best health state imaginable).35

- -

VR-related outcomes, such as self-perceived grade of acceptance, usability, and satisfaction, will be assessed using the System Usability Scale (SUS),36 which has been validated in a Spanish version (10 questions with answers from 1 [lower] to 5 [higher]); Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ) to assess cybersickness or secondary effects of VR (translated and adapted for the Spanish population)37; SEQ (Single Ease Question), which is a simple yet effective method of quantitative usability testing.38 Additionally, ad hoc tables will be prepared to register adverse events, self-perceived difficulty, satisfaction, enjoyment, and falls during the intervention. Adherence to the exercise intervention program will be documented during a daily registry session along with The Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) BORGCR10 scale, which measures an individual's effort, exertion, breathlessness, and fatigue during physical work, and is highly relevant for occupational health and safety practices.39

Acute hospitalization often results in new functional and cognitive disabilities among older adults as a side effect. This project is significant because it focuses on developing individualized, multicomponent programs to address and prevent functional decline in acutely hospitalised older adults by incorporating innovative technologies.

Advances in technology are rapidly arising concurrently with population aging, creating potential benefits for integrating technology into care for older adults. It is true that a digital divide still exists between the younger and older generations, although older adults demonstrate not only increasing use of current technologies but also have positive opinions on it.40–43 The development of technology generates new opportunities to support and facilitate older adults who may gain the most from it.44 However, older adults are often excluded from many research studies, leading to a lack of knowledge on the potential benefits of these technologies in older adults.

This randomized controlled trial explores the effects of IVR combined with multicomponent exercise programs on functional and cognitive abilities of hospitalized older adults. This study evaluates the implementation of IVR not only from a clinical perspective, by assessing whether it provides greater motivation and willingness to exercise and, therefore, greater improvement, but also in terms of mood, perceived quality of life, and feasibility. If our hypothesis proves accurate, this project will pave the way for modifying the hospitalization system to keep up with time, helping to reduce the critical healthcare burden resulting from the common hospital-acquired disability in the older population.

Status of trialThe trial is currently open to recruitment. Recruitment will be halted when 255 participants will be assigned randomly. The trial was retrospectively registered at ClinicalTrials.gov registration number NCT06469554.

Authors’ contributionsFZF and NMV contributed to the study conception, design, and project planning. MCF, FZF, AG, MFR, MGI, AGB, AC, SD, IM, FZF and NMV developed the protocol. AG provided advice on statistical analysis. MCF prepared the initial manuscript. All authors read, reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participateThis study was approved by the Navarra Clinical Research Ethics Committee (PI_2021_90, June 14th, 2021). Any important protocol modifications will be notified to relevant parties. Informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians through signed documents.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

FundingThis study was funded by the Government of Navarra (Exp. G°Na 10/21) and co-financed by the European Union (FEDER 2014-2020).

Conflict of interestsGiven his role as Member of the Editorial Board as Editor-in-Chief, Nicolás Martínez-Velilla will not participate in the peer review of this article and has not accessed the peer review information.

The other authors have no conflicts of interest.

Availability of data and materialsThe datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Access to data using identifiers is strictly restricted by authorized study team members and authorities. Electronic data will be securely stored on a server regulated by a local research institute (NAVARRABIOMED).

We extend our gratitude to all patients and their families for their confidence in the research team.