The Spanish National Hip Fracture Registry (or Registro Nacional de Fractura de Cadera, RNFC) is a database of hip fracture patients admitted to Spanish hospitals. Its goals include assessment and continuous improvement of the care process.

ObjectivesTo (1) establish a series of indicators, (2) evaluate their initial fulfillment, (3) propose quality standards, (4) suggest recommendations to facilitate standards compliance, and (5) monitor the indicators.

MethodThe indicators fulfilled the criteria of (1) evaluating the process or outcome, (2) being clinically relevant for patients, (3) being modifiable through changes in healthcare practice, and (4) being considered important by the RNFC participants. The first quartile obtained by the group of hospitals in each of the respective variables was proposed as the standard. The Indicators Advisory Committee (IAC) elaborated a list of recommendations for each indicator, based on the available evidence.

ResultsSeven indicators were chosen. These indicators (its baseline compliance vs. the standard to be reached, respectively) were: the proportion of patients receiving surgery within 48h (44% vs. 63%), mobilized the first postoperative day (56% vs. 86%), with antiosteoporotic medication at discharge (32% vs. 61%), with calcium supplements at discharge (46% vs. 77%), with vitamin D supplements at discharge (67% vs. 92%), who developed pressure ulcers during hospitalization (7.2% vs. 2.1%) and with independent mobility at 30 days (58% vs. 70%). The IAC has established 25 recommendations for improving care.

ConclusionThe indicators and standards chosen are presented, as well as the list of recommendations. This process completes the first step to improve quality of care. The results will be evaluated 6 months after implementing the recommendations.

El Registro Nacional de Fractura de Cadera (RNFC) es una base de datos de pacientes con fractura de cadera ingresados en hospitales españoles. Entre sus objetivos se encuentran el conocimiento y la mejora continua del proceso asistencial.

Objetivos1) establecer una serie de indicadores, 2) evaluar su cumplimiento inicial, 3) proponer unos estándares, 4) sugerir recomendaciones para facilitar el cumplimiento de los estándares y 5) realizar una monitorización de los indicadores.

MétodoLos indicadores cumplían los criterios de: 1) evaluar proceso o resultados, 2) tener relevancia clínica para los pacientes, 3) ser potencialmente modificables mediante cambios en la práctica asistencial y 4) ser considerados importantes por los participantes del RNFC. Se propuso como estándar el primer cuartil obtenido por el grupo de hospitales en cada una de las variables respectivas. El Comité de Indicadores (CI) elaboró una lista de recomendaciones basadas en la evidencia disponible.

ResultadosSe eligieron 7 indicadores. Estos indicadores (con su grado de cumplimiento inicial vs. el estándar a alcanzar, respectivamente) fueron la proporción de pacientes intervenidos en menos de 48h (44 vs. 63%), levantados el primer día del postoperatorio (56 vs. 86%), con tratamiento anti-osteoporótico al alta (32 vs. 61%), con tratamiento de calcio al alta (46 vs. 77%), con tratamiento de vitamina D al alta (67 vs. 92%), que desarrollaron úlceras por presión durante la hospitalización (7,2 vs. 2,1%) y con movilidad independiente a los 30 días (58 vs. 70%). El CI ha establecido una serie de 25 recomendaciones para la mejora asistencial.

ConclusiónSe presentan los indicadores y estándares elegidos, así como las recomendaciones. Este proceso completa el primer paso de mejora de calidad asistencial, cuyo resultado deberá ser evaluado tras 6 meses de implementación de las recomendaciones elegidas.

The Spanish National Hip Fracture Registry (SNHFR, or Registro Nacional de Fractura de Cadera, RNFC) is a database of hip fracture patients admitted to Spanish hospitals. Its goals include assessment and continuous improvement of the care process.1

This improvement should focus on aspects considered important for patients and as a priority by the members of the SNHFR, and according to the criteria defined by experts in other audits and clinical guidelines.

In order to obtain potentially achievable results in real practice, goals should be set in line with the healthcare environment in which we find ourselves, and one possible approach is to attempt to achieve the results of the best hospitals of the group in each aspect.

The objectives of this document are: (1) to establish an initial series of process and outcome indicators, (2) evaluate their initial fulfillment, (3) propose quality standards of these indicators to be achieved, (4) suggest some recommendations to the participating hospitals in order to facilitate compliance with the standards, and (5) to carry out continuous monitoring of the indicators and feedback with the participating hospitals.

Regardless of the degree of improvement in each center, it is intended, above all, to achieve a global improvement, evaluated through a common result of all the hospitals included in the Registry.

MethodFirst phase (first semester of 2018): Based on data from the 48 hospitals that registered a total of 3071 cases between January and May 2017, a series of 9 indicators were selected that met the criteria of (1) evaluating the process or outcome, (2) being clinically relevant for patients, (3) being modifiable through changes in healthcare practice, and (4) being considered important by the RNFC participants. Once chosen, a standard was proposed as an objective to be achieved by the participating centers. The proposed standard, expressed as a proportion (in the sense of percentage or frequency), was the first quartile obtained by the group of all hospitals in each of the respective variables in this time period.

Second phase (second semester of 2018): The local Registry coordinators of the participating hospitals were informed of the chosen indicators and standards, as well as a proposal with concrete and practical measures to achieve them. The chosen indicators were presented and discussed at the First National Meeting of the SNHFR on February 23rd, 2018, and their number was reduced to 7. The proposed recommendations were sent through the official audit newsletter to all local coordinators on August 31st and October 8th, 2018.

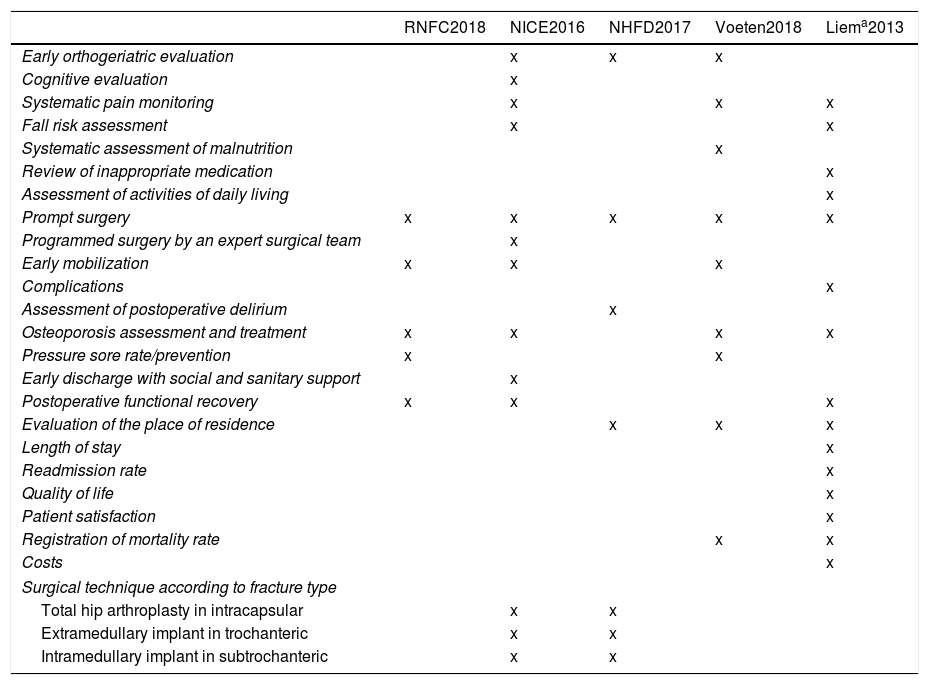

These newsletters included a request to submit comments and points of view regarding the original draft, some of which were incorporated into the current version. The investigators who replied contributing suggestions are mentioned in the acknowledgements section of this paper. A very interesting aspect that emerged from this exchange was the proposal of comparison with quality indicators and outcome parameters suggested by other authors. The results of this comparison are shown in Table 1, which shows a remarkable variability of indicators proposed by the different sources, as is logical, since their origins differs. One of them is a clinical practice guideline (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, NICE),2 another a registry (National Hip Fracture Database, NHFD),3 a third comes from a systematic literature review (Voeten et al.)4 and still another from the recommendations of a group of experts (endorsed by the AOTrauma Network).5 It is noteworthy that all indicators chosen by the SNHFR except one (the rate of pressure ulcers) are also mentioned by at least two of the other sources.

Comparison of the indicators and outcome parameters for the measurement of quality of care for hip fractures proposed by different authors.

| RNFC2018 | NICE2016 | NHFD2017 | Voeten2018 | Liema2013 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early orthogeriatric evaluation | x | x | x | ||

| Cognitive evaluation | x | ||||

| Systematic pain monitoring | x | x | x | ||

| Fall risk assessment | x | x | |||

| Systematic assessment of malnutrition | x | ||||

| Review of inappropriate medication | x | ||||

| Assessment of activities of daily living | x | ||||

| Prompt surgery | x | x | x | x | x |

| Programmed surgery by an expert surgical team | x | ||||

| Early mobilization | x | x | x | ||

| Complications | x | ||||

| Assessment of postoperative delirium | x | ||||

| Osteoporosis assessment and treatment | x | x | x | x | |

| Pressure sore rate/prevention | x | x | |||

| Early discharge with social and sanitary support | x | ||||

| Postoperative functional recovery | x | x | x | ||

| Evaluation of the place of residence | x | x | x | ||

| Length of stay | x | ||||

| Readmission rate | x | ||||

| Quality of life | x | ||||

| Patient satisfaction | x | ||||

| Registration of mortality rate | x | x | |||

| Costs | x | ||||

| Surgical technique according to fracture type | |||||

| Total hip arthroplasty in intracapsular | x | x | |||

| Extramedullary implant in trochanteric | x | x | |||

| Intramedullary implant in subtrochanteric | x | x | |||

RNFC: Registro Nacional de Fractura de Cadera, SNHFR; NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NHFD: National Hip Fracture Database.

Third phase (for seen for the year 2019): Evaluation of the chosen indicators in a second analysis that includes the data for 2019 by trimesters, in the same hospitals that has already participated in the time period of the first phase of the study. Quantification of change by measuring the indicators globally for all centers, independently of whether each hospital wished to evaluate its individual improvement.

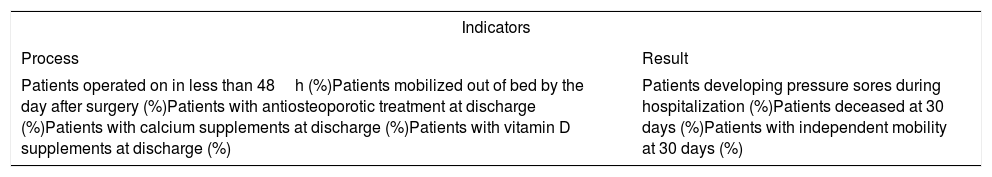

ResultsChoice of specific indicators and definition of standardsInitially, the indicators presented in Table 2 were selected, as they fulfilled the aforementioned criteria. These indicators were presented during the 1st Meeting of the SNHFR, which took place in Madrid on February 23rd, 2018.

Initial selection of indicators.

| Indicators | |

|---|---|

| Process | Result |

| Patients operated on in less than 48h (%)Patients mobilized out of bed by the day after surgery (%)Patients with antiosteoporotic treatment at discharge (%)Patients with calcium supplements at discharge (%)Patients with vitamin D supplements at discharge (%) | Patients developing pressure sores during hospitalization (%)Patients deceased at 30 days (%)Patients with independent mobility at 30 days (%) |

Subsequently, it was decided to rule out (1) the proportion of patients who underwent surgery, because its overall result was already close to 100%, and (2) the proportion of patients deceased at 30 days, because the average frequency (6.7%) was very close to the standard (5.4%), and because it was felt that this was a very difficult goal to achieve at this stage of the SNHFR.

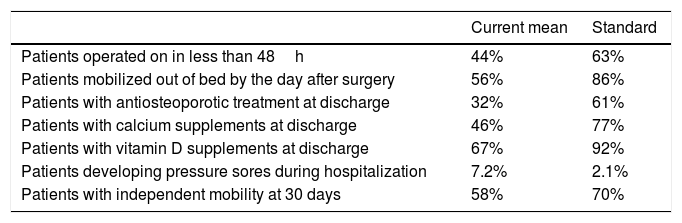

The resulting indicators are shown in Table 3, with the overall average proportion measured for all hospitals and the data from the first quartile (25% of the hospitals with the best results of the respective variable in the database) as reported in the 2nd Report (2017).

Final selection of indicators and definition of quality standards.

| Current mean | Standard | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients operated on in less than 48h | 44% | 63% |

| Patients mobilized out of bed by the day after surgery | 56% | 86% |

| Patients with antiosteoporotic treatment at discharge | 32% | 61% |

| Patients with calcium supplements at discharge | 46% | 77% |

| Patients with vitamin D supplements at discharge | 67% | 92% |

| Patients developing pressure sores during hospitalization | 7.2% | 2.1% |

| Patients with independent mobility at 30 days | 58% | 70% |

Justification: Surgery in the first 48h following hip fracture has been proven to reduce in-hospital, 30-day and 1-year mortality. In addition, it is a prognostic factor of functional recovery. Furthermore, the incidence of common medical complications such as delirium, anemia and the development of pressure sores increases with increasing the preoperative waiting time. Patients with many comorbidities and the most deteriorated from a clinical viewpoint are the ones most likely to benefit from prompt surgery, once stabilized for the procedure. Finally, surgical delay has an evident impact on hospital length of stay.4,6–9

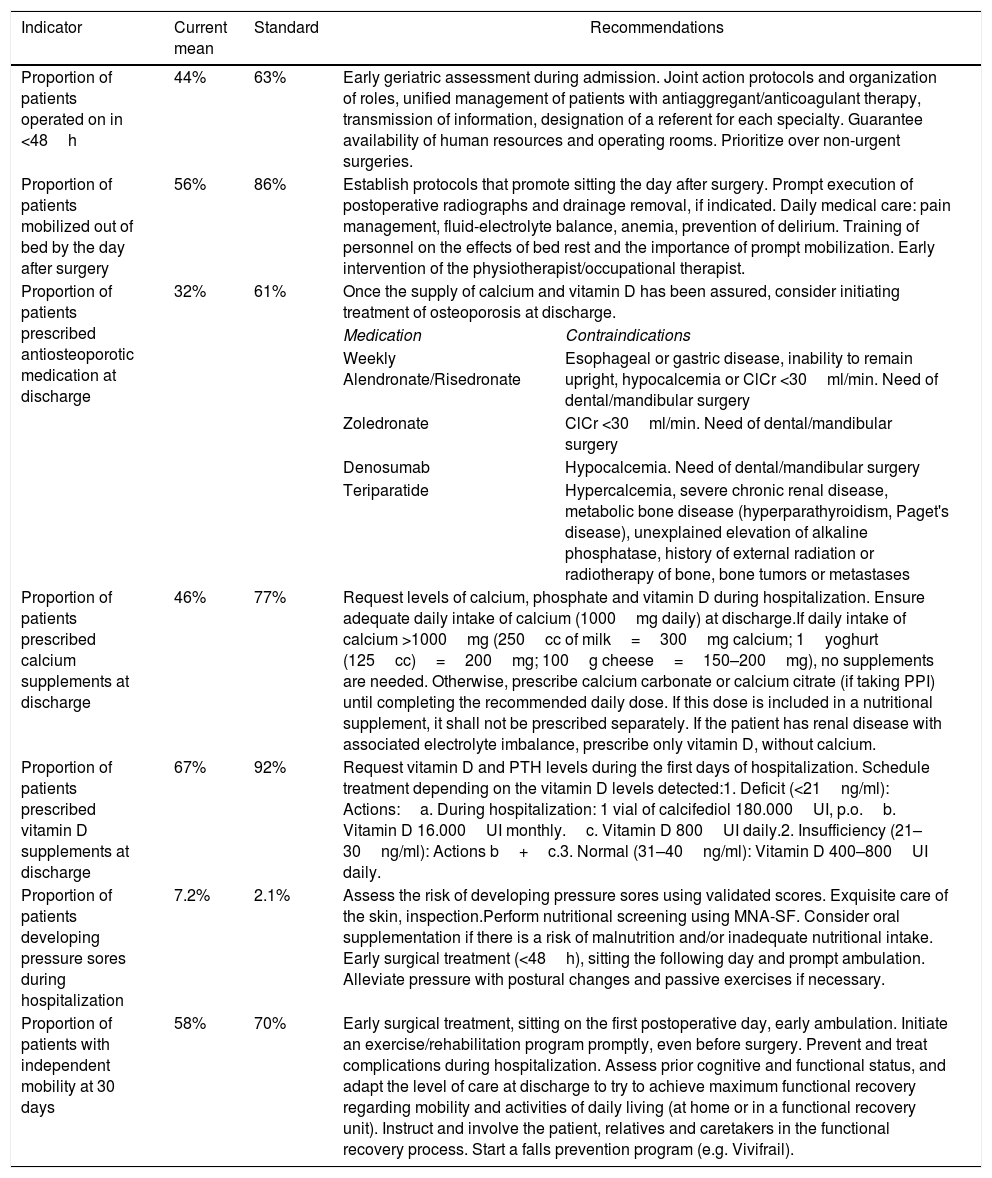

Proposed recommendations to achieve the quality standards of the Spanish National Hip Fracture registry (SNHFR, Registro Nacional de Fractura de Cadera, RNFC).

| Indicator | Current mean | Standard | Recommendations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of patients operated on in <48h | 44% | 63% | Early geriatric assessment during admission. Joint action protocols and organization of roles, unified management of patients with antiaggregant/anticoagulant therapy, transmission of information, designation of a referent for each specialty. Guarantee availability of human resources and operating rooms. Prioritize over non-urgent surgeries. | |

| Proportion of patients mobilized out of bed by the day after surgery | 56% | 86% | Establish protocols that promote sitting the day after surgery. Prompt execution of postoperative radiographs and drainage removal, if indicated. Daily medical care: pain management, fluid-electrolyte balance, anemia, prevention of delirium. Training of personnel on the effects of bed rest and the importance of prompt mobilization. Early intervention of the physiotherapist/occupational therapist. | |

| Proportion of patients prescribed antiosteoporotic medication at discharge | 32% | 61% | Once the supply of calcium and vitamin D has been assured, consider initiating treatment of osteoporosis at discharge. | |

| Medication | Contraindications | |||

| Weekly Alendronate/Risedronate | Esophageal or gastric disease, inability to remain upright, hypocalcemia or ClCr <30ml/min. Need of dental/mandibular surgery | |||

| Zoledronate | ClCr <30ml/min. Need of dental/mandibular surgery | |||

| Denosumab | Hypocalcemia. Need of dental/mandibular surgery | |||

| Teriparatide | Hypercalcemia, severe chronic renal disease, metabolic bone disease (hyperparathyroidism, Paget's disease), unexplained elevation of alkaline phosphatase, history of external radiation or radiotherapy of bone, bone tumors or metastases | |||

| Proportion of patients prescribed calcium supplements at discharge | 46% | 77% | Request levels of calcium, phosphate and vitamin D during hospitalization. Ensure adequate daily intake of calcium (1000mg daily) at discharge.If daily intake of calcium >1000mg (250cc of milk=300mg calcium; 1yoghurt (125cc)=200mg; 100g cheese=150–200mg), no supplements are needed. Otherwise, prescribe calcium carbonate or calcium citrate (if taking PPI) until completing the recommended daily dose. If this dose is included in a nutritional supplement, it shall not be prescribed separately. If the patient has renal disease with associated electrolyte imbalance, prescribe only vitamin D, without calcium. | |

| Proportion of patients prescribed vitamin D supplements at discharge | 67% | 92% | Request vitamin D and PTH levels during the first days of hospitalization. Schedule treatment depending on the vitamin D levels detected:1. Deficit (<21ng/ml): Actions:a. During hospitalization: 1 vial of calcifediol 180.000UI, p.o.b. Vitamin D 16.000UI monthly.c. Vitamin D 800UI daily.2. Insufficiency (21–30ng/ml): Actions b+c.3. Normal (31–40ng/ml): Vitamin D 400–800UI daily. | |

| Proportion of patients developing pressure sores during hospitalization | 7.2% | 2.1% | Assess the risk of developing pressure sores using validated scores. Exquisite care of the skin, inspection.Perform nutritional screening using MNA-SF. Consider oral supplementation if there is a risk of malnutrition and/or inadequate nutritional intake. Early surgical treatment (<48h), sitting the following day and prompt ambulation. Alleviate pressure with postural changes and passive exercises if necessary. | |

| Proportion of patients with independent mobility at 30 days | 58% | 70% | Early surgical treatment, sitting on the first postoperative day, early ambulation. Initiate an exercise/rehabilitation program promptly, even before surgery. Prevent and treat complications during hospitalization. Assess prior cognitive and functional status, and adapt the level of care at discharge to try to achieve maximum functional recovery regarding mobility and activities of daily living (at home or in a functional recovery unit). Instruct and involve the patient, relatives and caretakers in the functional recovery process. Start a falls prevention program (e.g. Vivifrail). | |

PPI: proton pump inhibitor; MNA-SF: Mini Nutritional Assessment – Short Form; ClCr: creatinine clearance.

Goal: The current surgical delay averages 75h. 44% of patients included in the registry are operated on in less than 48h. The aim is for 63% of patients to be operated on in less than 48h.

Recommendations (Table 4)10–14:

- -

Medical assessment from the time of admission, ensuring the patient's clinical stability for prompt surgery: cardiopulmonary stabilization, control of anemia, correction of electrolyte imbalance, medication reconciliation, measures to prevent medical complications.

- -

Establishment of joint action protocols with Orthopedic Surgery and Anesthesiology regarding: (1) the duties of each member of the therapeutic team, as well as the moment and place each of these should be carried out, (2) the course of action in case of treatment with platelet antiaggregants/anticoagulants drugs, (3) the transmission of information among members of the therapeutic team.

- -

The appointment of a designated orthopedic surgeon responsible for surgical scheduling, coordinated with a single anesthesiologist, can improve surgical delay.

- -

The availability of human resources and infrastructure to ensure surgical scheduling without delay.

- -

Adjustment of operating room scheduling, attempting to have daily slots available for hip fracture surgery.

Justification: Early mobilization following surgery is a determinant of survival and functional recovery following hip fracture surgery. The consequences of the loss of bone and lean muscle mass due to immobility, as well as the increased risk of medical, respiratory and other types of complications make it paramount to minimize the time spent in bed. Prompt mobilization after surgery provides better pain control and improve the perceived quality of life. Furthermore, the return to the prior social situation is related to mobilization in the first 24h after surgery.4,6,9

Goal: The current proportion of patients mobilized out of bed by the day after surgery is 56%. The aim is to achieve 86%.

Recommendations (Table 4):

- -

To establish local protocols that promote sitting the day after surgery.

- -

To formalize the prompt execution of postoperative control radiographs.

- -

To formalize prompt removal of postoperative surgical drainages.

- -

Daily medical care concerning adequate pain control, monitorization of anemia, fluid-electrolyte balance in order to avoid postoperative hypotension, as well as preventative measures against delirium.

- -

Training of staff (nurses, nurse assistants, orderlies) regarding the negative effects of bed rest and the importance of early mobilization, and organization of the ward to facilitate sitting the first day after surgery.

- -

Early intervention of the physiotherapist/occupational therapist.

Justification: One of the most important risk factors for suffering a fragility fracture is having a history of a previous fracture.15,16 Several clinical practice guidelines on the management of osteoporosis17–23 recommend initiating antiosteoporotic treatment as secondary prevention following a hip fracture, since it can reduce the risk of new fractures up to 50% and is cost-effective.12,24 The current recommendation is that after a fragility hip fracture, patients should receive treatment for osteoporosis, without needing densitometric assessment of bone mineral density.17,18,20

The currently recommended drugs are: alendronate, risedronate, zoledronate, denosumab and teriparatide.17,18,20,22,24,25

Oral bisphosphonates (alendronate, risedronate) are the first-line treatment for osteoporosis in patients with hip fracture,17–19,22,24 followed by intravenous zoledronate in patients who are bedridden, have gastrointestinal comorbidities or poor tolerance to the oral treatment.17–19,22 In case of contraindication, intolerance, poor compliance or treatment failure, it is recommended to initiate treatment with denosumab.17,18,22,25 For patients with a high risk of osteoporotic fractures (in which there have been more than 2 vertebral fractures or a vertebral and a non-vertebral fracture) or with therapeutic failure, bone-forming treatment with teriparatide may be an alternative.17,18,22

According to current evidence, the use of bisphosphonates and denosumab is safe when administered immediately after the fracture or surgery itself, without impeding callus formation, with the exception of zoledronate, which is recommended to be initiated at least two weeks after the fracture.26

It is advised that all drugs used in the treatment of osteoporosis (antiresorptive, anabolic) be prescribed along with calcium and vitamin D.12,17–20,22,24

Goal: The current proportion of patients with antiosteoporotic treatment at discharge is 32%. The aim is to achieve 61%.

Recommendations (Table 4): Once calcium and vitamin D intake are assured, the initiation of treatment for osteoporosis at the time of discharge is to be assessed.

Indicator 4: Proportion of patients with calcium supplementation at dischargeJustification17–20,22: Simultaneous administration of calcium and vitamin D has shown a benefit in reducing the risk of hip fractures. For this reason, an adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D is to be ensured in hip fracture patients. Clinical practice guidelines recommend a daily intake of 1000 to 1200mg of calcium, preferably through dietary intake. If this not possible through the diet, treatment with oral supplements should be considered.

Goal: The current proportion of patients with calcium treatment is 46%. The aim is to reach 77%.

Recommendations (Table 4):

- -

Request calcium, phosphate and vitamin D levels during hospitalization.

- -

Ensure adequate calcium intake at discharge. If daily intake is over 1000mg (250cc milk=300mg calcium; 1 yoghurt (125cc)=200mg; 100g cheese=150–200mg)20 calcium supplements are not necessary.

- -

Otherwise, a supplement is prescribed: calcium carbonate (first line) or calcium citrate (if treated with proton pump inhibitors).

- -

If this dose is included in the nutritional supplement, it will not be prescribed separately.

- -

If the patient has significant kidney disease with associated electrolyte disorders, only vitamin D should be prescribed, without calcium. If patient is on dialysis or treated by nephrology, the treatment prescribed by said department should be continued.

Justification: Vitamin D deficit is very common among hip fracture patients, with rates over 90%.17 Vitamin D deficit in hip fracture patients has been associated with worse functional recovery at discharge and one year after hip fracture, and with and increased risk of falls in the year following hip fracture.27

Vitamin D supplementation facilitates and improves the fracture healing process,17 favors functional recovery, decreases the risk of falls and could improve 1-year survival following a hip fracture.27–29 The combined treatment of vitamin D and calcium has shown a beneficial effect in reducing the rate of hip fractures.17–20,22

The clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of osteoporosis recommend a physiological intake of 800UI of vitamin D daily, with the aim of maintaining blood levels close to 40ng/ml,17–20,22 and avoid exceeding 50ng/ml.18 The amount necessary to replenish the deposits should be added to this daily physiological dose.

Goal: The current proportion of patients with vitamin D supplements at discharge is 67%. The aim is to achieve 92%.

Recommendations (Table 4):

- -

Request vitamin D and PTH levels in the first days of admission.

- -

Schedule treatment according to the vitamin D levels detected:

- 1.

Deficit (<21ng/ml). Actions:

- a.

During hospitalization, 1 vial of calcifediol 180.000UI, p.o.

- b.

Vitamin D 16.000UI monthly.

- c.

Vitamin D 800UI daily.

- a.

- 2.

Insufficiency (21–30ng/ml): Actions b+c.

- 3.

Normal (31–40ng/ml): Vitamin D 400–800UI daily.

- 1.

- -

Among the existing alternatives, calcifediol and cholecalciferol, calcifediol has some advantages because it is more powerful (it requires 3 times less dose to reach similar concentrations), increases 25-OH-D faster and more sustainably than cholecalciferol, and has a higher rate of intestinal absorption than the latter.30,31

Justification: Elderly people have a high risk of developing pressure sores during hospitalization, even greater among those suffering a hip fracture.32,33 According to the WHO, pressure sores are an indicator of poor quality of care in different socioeconomic institutions, constituting a serious and avoidable complication in more than 95% of cases.34 There are many risk factors for the development of pressure sores: age, malnutrition, the greater susceptibility of skin to shearing, pressure and friction, immobility, lack of hygiene, humidity of absorbents, having suffered a pressure sore previously, cognitive decline, anemia, diabetes mellitus, etc.35 These ulcers can cause localized and systemic pain and infections, increasing length of stay and morbimortality,35 worsening the quality of life of the patients and their families, hindering functional recovery, with a great economic impact and the perception of poor quality of care, even with legal implications. The SNHFR includes the presence of pressure sores grade 2 or above, newly developed during hospitalization.

Goal: The current proportion of patients developing pressure sores during hospitalization is 7.2%. The objective is to reduce it to 2.1%.

Recommendations (Table 4):

- -

Prevention, early detection and care of the patient at risk for or suffering a pressure sore should be part of nursing care in patients with hip fractures.

- -

Evaluation of the risk of suffering pressure sores, using validated scores such as Braden, Norton, Waterlow or EMINA.36

- -

Exquisite care of the skin, including regular inspection, preferably of areas with bony protrusions and where erythema, redness or lesions can be observed.

- -

Perform a systematic nutritional screening with validated instruments, such as the Mini Nutritional Assessment in its abbreviated form (MNA-SF)37 and assess the use of nutritional supplements in case of risk of malnutrition or inadequate intake.33

- -

Perform prompt surgical treatment (in less than 48h), as well as sedestation (the first postoperative day) and ambulation.

- -

In case of inability to walk, perform passive exercises and postural changes adapted to the patient's situation.

- -

Consider the use of special devices for pressure management.

Justification: Hip fracture can lead to the loss of the ability to walk, and to perform basic and instrumental activities of daily living independently.38 This functional decline and dependence becomes chronic in many cases, and is predictive of institutionalization, hospital readmissions, the development of cognitive decline, the risk of new falls and mortality.5,39,40 In addition, functional decline not only deteriorates quality of life, it also increases healthcare costs.5

Among the predictive factors of a better short-term (1–3 months) functional recovery following hip fracture, there are some that can be modified, such as: adequate control of pain in the hip, allowing weightbearing on the affected limb at hospital discharge, early ambulation,41 partial recovery of basic activities of daily living at the time of discharge, not suffering delirium after the fracture, being motivated for recovery, the prior level of occupation, and medical follow-up by geriatricians during the acute phase.39

Goal: The current proportion of patients with independent ambulation in- or outdoors 30 days after the fracture is 58%. The objective is to reach 70%.

Recommendations (Table 4):

- -

Early surgical treatment (less than 48h after fracture), sitting (on the first postoperative day) and ambulation (on the second postoperative day).

- -

Initiate an exercise and rehabilitation program early, even before surgery if it has to be delayed.

- -

Prevent and treat complications during hospitalization.

- -

Evaluate the previous cognitive and functional status, and adapt the level of care at discharge to try to achieve maximum functional recovery regarding mobility and activities of daily living (at home or in a functional recovery unit).42

- -

Instruct and involve the patient, relatives and caregivers in the process of functional recovery.

- -

Start a falls prevention program: e.g. Vivifrail.43

In this paper, a series of quality indicators and standards related to the hip fracture care process are proposed, and a series of recommendations to improve care are suggested. This list of recommendations does not intend to be a clinical practice guideline, though it is based on these, nor does it intend to replace practices that are established in each hospital, with the best clinical criteria in each patient, nor does it wish to rigidly homogenize the management of patients with hip fractures. Its main purpose is to suggest a series of measures that can be used as a checklist for a more systematic management of these patients than previously, or as an initiative for teams that did not have them previously and can use them as a starting point to achieve better results.

Conflicts of interestThe following authors have no conflicts of interest to declare: Teresa Alarcón Alarcón, Paloma Gómez Campelo, Laura Navarro Castellanos, Ángel Otero Puime.

The following authors declare:

Patricia Ysabel Condorhuamán Alvarado has received financial aid for attendance to scientific events from Nutricia Advanced Medical Nutrition, AMGEN SA and FAES Farma.

Teresa Pareja Sierra has received financial aid for attendance to scientific events from AMGEN SA and Vifor Pharma; and has received speakers’ honoraria from Abbott Laboratories SA.

Angélica Muñoz Pascual has received financial aid for attendance to scientific events from Lilly, Abbott Laboratories SA and AMGEN SA.

Pilar Sáez López has received financial aid for attendance to scientific events from Nutricia Advanced Medical Nutrition and Nestlé; and has received speakers’ honoraria from Abbott Laboratories SA and AMGEN SA.

Cristina Ojeda Thies has received financial aid for attendance to scientific events from AMGEN SA and UCB Pharma; and has received speakers’ honoraria from AMGEN SA and MBA.

María Concepción Cassinello Ogea has received financial aid for attendance to scientific events from CSL Behring; and has received speakers’ honoraria from Fresenius, Baxter and Vifor Pharma.

Jose Luis Pérez Castrillón has received financial aid for attendance to scientific events from AMGEN SA and MSD; and has received speakers’ honoraria from AMGEN SA, MSD, Lilly and FAES Farma.

Juan Ignacio González Montalvo has received speakers’ honoraria from AMGEN SA, Nutricia Advanced Medical Nutrition and Nestlé; and has coordinated educational activities financed by Nutricia Advanced Medical Nutrition, AMGEN SA and GSK.

For their contributions in the revision of the manuscript and proposals for improvement: Dr. Carmen Barrero, Dr. Marta Neira, Dr. José R. Caeiro, Dr. Eugenia Sopena, Dr. Jesús Mora and Dr. Nuria Montero. This project was funded by AMGEN SA, UCB Pharma SA, Abbott Laboratories SA and FAES Farma, as well as a research grant awarded by the Fundación Mutua Madrileña (grant number AP169672018). The sponsors did not influence any aspect of the project nor the drafting of the manuscript. The authors wish to thank Mr. Jesús Martín García from BSJ Marketing for his administrative help.