Pre-operative delay in patients with hip fracture surgery (HF) has been associated with poorer outcomes; however, the optimal timing of discharge from hospital after surgery has been little studied. The aim of this study was to determine mortality and readmission outcomes in HF patients with and without early hospital discharge.

Material and methodsA retrospective observational study was conducted selecting 607 patients over 65years of age with HF intervened between January 2015 and December 2019, from which 164 patients with fewer comorbidities and ASA≤II were included for analysis and divided according to their post-operative hospital stay into early discharge or stay ≤4 days (n=115), and non-early or post-operative stay >4days (n=49). Demographic characteristics; fracture and surgical-related characteristics; 30-day and one-year post-operative mortality rates; 30-day post-operative hospital readmission rate; and medical or surgical cause were recorded.

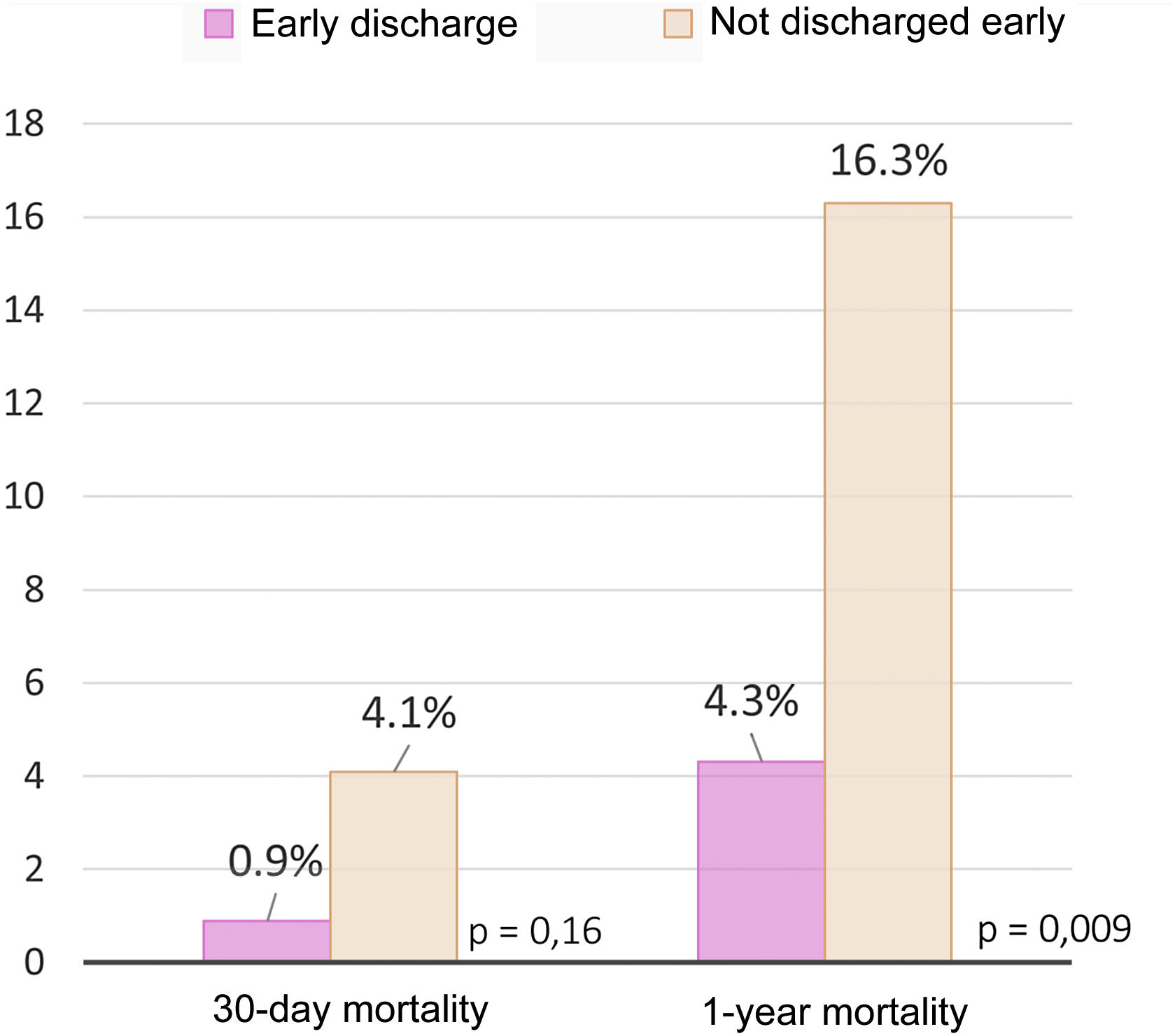

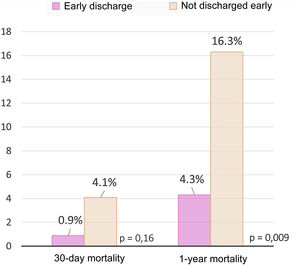

ResultsIn the early discharge group all outcomes were better compared to the non-early discharge group: lower 30-day (0.9% versus 4.1%, p=.16) and 1-year post-operative (4.3% versus 16.3%, p=.009) mortality rates, as well as a lower rate of hospital readmission for medical reasons (7.8% versus 16.3%, p=.037).

ConclusionsIn the present study, the early discharge group obtained better results 30-day and 1-year post-operative mortality indicators, as well as readmission for medical reasons.

El retraso preoperatorio en pacientes intervenidos de fractura de cadera (FC) se ha asociado a peores resultados, sin embargo, el momento óptimo del alta hospitalaria tras cirugía ha sido poco estudiado. El objetivo de este estudio fue determinar resultados de mortalidad y de reingreso en pacientes con FC con y sin alta hospitalaria precoz.

Material y métodosSe realizó un estudio observacional retrospectivo seleccionando a 607 pacientes mayores de 65 años con FC intervenidos entre enero de 2015 y diciembre de 2019, de los que se incluyeron para el análisis 164 pacientes con menos comorbilidades y ASA ≤ II y se dividieron según su estancia hospitalaria posoperatoria en alta precoz o estancia ≤ 4 días (n = 115) y alta no precoz o estancia posoperatoria > 4 días (n = 49). Se registraron características demográficas, características relacionadas con la fractura y el tratamiento quirúrgico, tasas de mortalidad a los 30 días y al año posoperatorio; tasa de reingreso hospitalario a los 30 días posoperatorios, y causa médica o quirúrgica.

ResultadosEn el grupo alta precoz todos los resultados fueron mejores frente al grupo no alta precoz: menor tasa de mortalidad a los 30 días posoperatorios (0,9 vs. 4,1%, p = 0,16) y al año posoperatorio (4,3 vs. 16,3%, p = 0,009), así como una menor tasa de reingreso hospitalario por razones médicas (7,8 vs. 16,3%, p = 0,037).

ConclusionesEn el presente estudio el grupo de alta precoz obtiene mejores resultados en indicadores de mortalidad a los 30 días y al año posoperatorio, así como de reingreso por causas médicas.

In recent years, some of the in-hospital factors that may have influenced mortality and complication rates in individuals undergoing hip fracture (HF) surgery have been studied. Hospital stay is one of these variables that have been studied.1 HF patients who do not develop complications following immediate surgery or before then stabilise approximately 4–5 days following surgery, at which point they may be transferred home or to intermediate care or rehabilitation centres to continue treatment on an outpatient basis.2,3 However, the data on mean hospital stay observed in the literature exceed 4–5 days, ranging from 7.3 to 12 days in Europe, while in Spain, the mean is 9.3 days, according to the latest data published by the National Hip Fracture Registry (RNFC) by Ríos Germán.4,5

Some authors have detected a greater likelihood of complications and hospital readmission,6–8 as well as increased difficulty in recovering function9 and poor use of hospital resources in those patients whose hospital stay is extended.10–12 In fact, measures to improve hospital stay have included creating multidisciplinary or orthogeriatric units (UOG),12–17 which have successfully reduced waiting times for patient assessment and treatment, decreasing the mean length of hospital stay.18–20

Most articles that analyse hospital stay fail to distinguish between pre-operative and post-operative stay. Pre-operative delay in HF patients has been associated with worse outcomes in numerous studies.21–26 Recent publications point to the importance of analysing the post-operative factors that affect hospital stay that affect surgical HF patients.27 The development of complications during hospitalisation have been described among the post-operative factors that lead to delayed discharge from hospital27; nevertheless, there are also causes associated with problems unrelated to the patient's medical condition, such as waiting to gain greater mobility and independence, home adaptation, family support, etc.11

The optimal time of discharge from hospital following surgery has been scarcely examined in the literature. Whether early discharge from hospital might increase the likelihood of adverse events, or whether, on the contrary, it may prove beneficial, especially in patients with less prior pathology and a lower degree of dependence, is not known.

Thus, the aim of the present study was to compare outcomes related to mortality and readmission in HF patients with fewer comorbidities or ASA≤II who were discharged early versus those who were not.

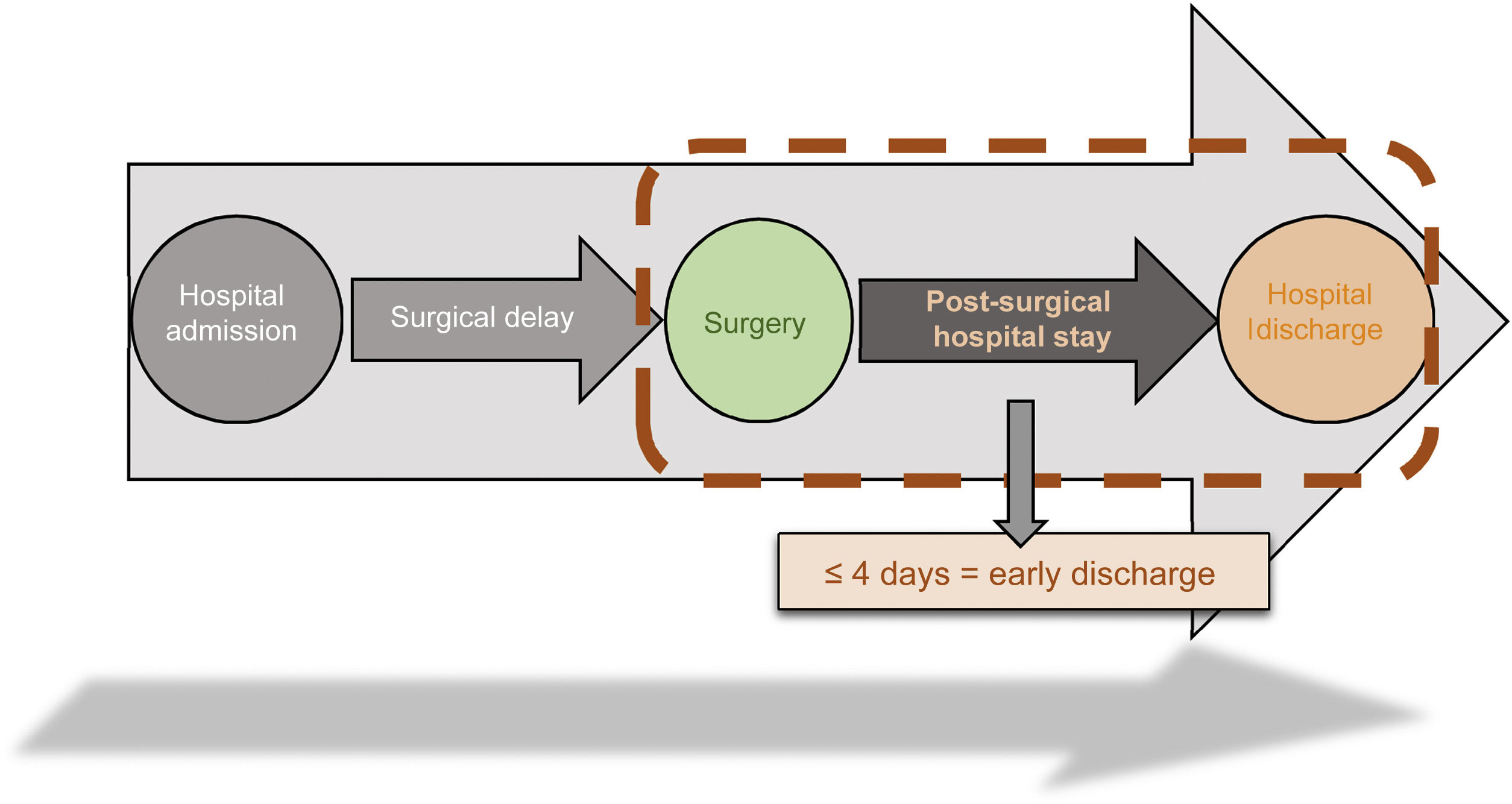

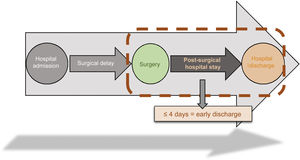

Material and methodsA retrospective observational study was conducted of all patients aged 65 years and older with HF who underwent surgery between January 2015 and December 2019. A total of 607 interventional HF cases were identified. Subjects with pathological, periprosthetic, and high-energy fractures, in addition to patients with major comorbidities or ASA≥III were excluded.28 Out of a total of 607 cases, 164 patients with few comorbidities and ASA≤II were included for analysis. Participants were divided on the basis of their post-operative stay as early discharge (defined as post-operative hospital stay≤4 days after surgery) (n=115) and not early discharge (defined as post-operative hospital stay>4 days after surgery) (n=49) (Fig. 1).

In both groups, demographic characteristics were recorded such as: age (which was treated as a qualitative variable dichotomised as a function of the mean age of the sample), sex, concomitant diseases (diabetes mellitus, previous history of rheumatic diseases, chronic alcoholism), chronic treatment with antithrombotic medication (anticoagulant or antiplatelet), degree of dementia on admission (using the data reported in the clinical history), degree of dependence by means of the Barthel scale score,29 degree of lymphopenia laboratory tests on admission (values of less than 1500/μl or 1.5×109/l). Variables related to surgery and treatment were also recorded: type of fracture (intracapsular or extracapsular), type of surgical treatment (osteosynthesis or arthroplasty), and pre-surgical delay>48h. As outcome variables, 30-day and one-year post-operative mortality were analysed, as well as 30-day post-operative hospital readmission and the cause of readmission, differentiating between medical reasons (respiratory infection, urinary tract infection, cardiac problems, etc.) or the need for surgery (surgical wound infection, prosthetic dislocations, failure of osteosynthesis material due to breakage, cephalic perforation with rotation and collapse in varus due to anterosuperior screw migration, etc.).

The statistical analysis was carried out with the SPSS programme (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0, Armonk, NY), establishing an error (α) of 5%, a 95% confidence level, as well as a p-value of 0.05. In the descriptive analysis, variables were described using absolute and relative frequencies. Comparative tables were elaborated containing demographic, patient, and fracture data, in addition to mortality and readmissions. For categorical variables with more than two categories, the decision was made to reduce their dimensions by grouping the categories into dichotomous categories. The fracture type variable was dichotomised into extracapsular or intracapsular, and type of treatment into osteosynthesis or arthroplasty. Continuous quantitative variables, such as age and Barthel dependency index score, were dichotomised according to the mean value. For the age variable, it was <83 years and >83 years, while for the Barthel index variable, it was <82 or >82 points. To compare the variables between the two groups, Chi-square tests (χ2) were used, and to detect whether early discharge was an independent factor in mortality in the one year following surgery, the binary logistic regression analysis model was used, including the variables that could impact the results (age>83 years, pre-operative delay>48h, Barthel index>82 points, degree of dementia, type of fracture, surgical treatment, previous history of diabetes mellitus, development of general post-operative complications, development of post-operative surgical wound complications, and early discharge).

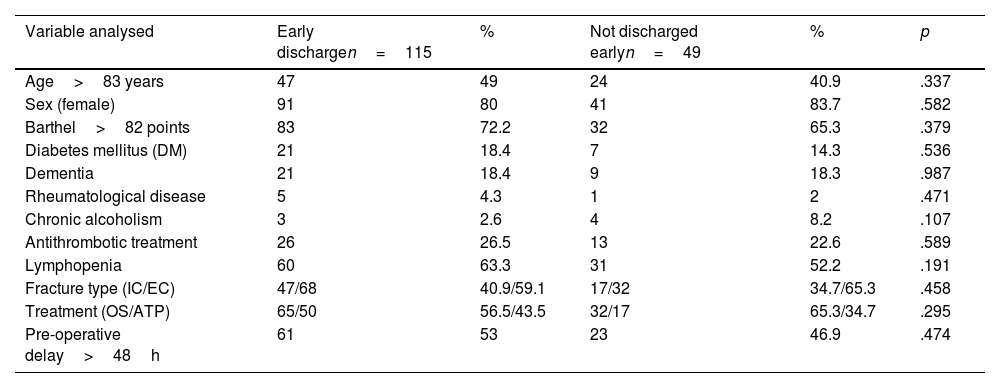

ResultsBoth groups were comparable, finding no statistically significant differences with respect to demographic characteristics, fracture location, or to type of treatment, as reported in Table 1.

Demographic characteristics, fracture- and treatment-related variables.

| Variable analysed | Early dischargen=115 | % | Not discharged earlyn=49 | % | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age>83 years | 47 | 49 | 24 | 40.9 | .337 |

| Sex (female) | 91 | 80 | 41 | 83.7 | .582 |

| Barthel>82 points | 83 | 72.2 | 32 | 65.3 | .379 |

| Diabetes mellitus (DM) | 21 | 18.4 | 7 | 14.3 | .536 |

| Dementia | 21 | 18.4 | 9 | 18.3 | .987 |

| Rheumatological disease | 5 | 4.3 | 1 | 2 | .471 |

| Chronic alcoholism | 3 | 2.6 | 4 | 8.2 | .107 |

| Antithrombotic treatment | 26 | 26.5 | 13 | 22.6 | .589 |

| Lymphopenia | 60 | 63.3 | 31 | 52.2 | .191 |

| Fracture type (IC/EC) | 47/68 | 40.9/59.1 | 17/32 | 34.7/65.3 | .458 |

| Treatment (OS/ATP) | 65/50 | 56.5/43.5 | 32/17 | 65.3/34.7 | .295 |

| Pre-operative delay>48h | 61 | 53 | 23 | 46.9 | .474 |

ATP: arthroplasty; EC: extracapsular; IC: intracapsular; OS: osteosynthesis.

The mortality rates reported were lower in the early discharge group in all subgroups. The mortality rate within the first 30 days postoperatively was 0.9% in the early discharge group compared to 4.1% in the non-early discharge group (p=0.16). The one-year post-surgery mortality in the early discharge group was 4.3% compared to 16.3% in the non-early discharge group; said difference was statistically significant (p=0.009) (OR: 0.233; 95% CI: 0.072–0.753) (Fig. 2).

Early discharge was found to be an independent factor in reducing the probability of one-year post-operative mortality (p=0.038) (OR: 0.267; 95%CI: 0.076–0.929) and age>83 years was identified as an independent risk factor for one-year post-operative mortality (p=0.005) (OR: 2.371; 95% CI: 2.173–14.769).

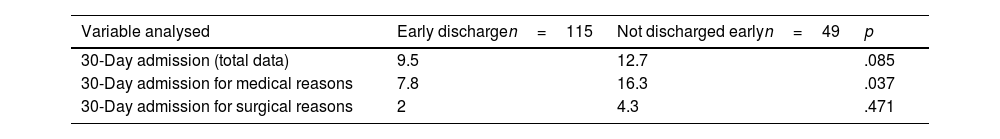

Hospital readmissionA lower 30-day readmission rate was observed in the early discharge group (9.5%) compared to the non-early discharge group (12.7%), albeit this difference failed to reach statistical significance in the analysis (p=0.085) (Table 2). A higher rate of readmission at 30 days for medical causes was reported in the non-early discharge group (16.3%) compared to the early discharge group (7.8%) and this difference was statistically significant in the analysis (p=0.037) (Table 2).

DiscussionThis patient sample comprised individuals of advanced age, mostly women, with extracapsular fractures, and pre-operative delay exceeding 48h, data that are in line with those found in the bibliography5,30 and in whom we observed a lower one-year mortality rate and hospital readmission for medical reasons in those patients who received an early discharge compared to those who did not.

In the studies published in the literature, we have detected a trend towards higher hospital readmission and mortality rates in patients with a longer hospital stay in the acute episode.6,7,20,31 For instance, Balvis-Balvis et al.20 reported a 6.4% reduction (p=0.004) in 30-day mortality rates among subjects in whom hospital stay was shortened by 3.4 days. However, in our series we noted a higher 30-day mortality rate in patients who were not discharged early versus those who were, although this was not statistically significant (4.1% versus 0.9%, respectively; p=0.16); nevertheless, the 1-year mortality rate was significantly higher in patients who were not discharged early versus those who were discharged early (16.3% versus 4.3%; p=0.009).

Other studies, such as those published by Pollock et al.7 and Heyes et al.,6 found that hospital stays>8 days and >7 days, respectively, were risk factors for hospital readmission at 30 days.

We cannot establish direct comparisons of the findings of previous studies6,20 with ours, as the mean and post-operative hospital stay data vary, given that the aim of the earlier studies did not focus on analysing post-operative hospital stay. Furthermore, despite the observed trend, the higher readmission and mortality results in the earlier studies could be influenced by other factors, such as worsening of the pathology prior to admission or the development of post-operative complications during hospital stay.

In our series, patients with greater comorbidities were excluded and the analysis considered the rate of post-operative complications (both medical and surgical) in both groups to minimise the possible influence of these factors on readmission and mortality outcomes, analysing only the potential beneficial effect of early discharge in patients with fewer comorbidities who underwent HF surgery.

As for the causes of hospital readmission in HF patients, the most common causes are medical issues rather than surgery-related problems. Lizaur-Utrilla et al.32 reported that readmissions for medical causes were thirteen times more frequent than readmissions for non-medical causes. In our series, as in the previous one, the most usual cause for hospital readmission was medical and was more common in the non-early versus early discharge group (16.3% versus 7.8%, respectively; p=0.037).

Delaying hospital discharge during the acute episode while waiting for greater mobility and independence prior to hospital discharge, home preparation, family support, etc., in patients with fewer comorbidities may be counterproductive, increasing their exposure to the adverse effects associated with hospitalisation. On the basis of our results, it seems safe to discharge early during the acute episode in HF patients with fewer comorbidities, with early discharge patients having statistically significantly lower rates of 1-year mortality and 30-day readmission for medical causes, in comparison to patients who were not discharged early. Moreover, we observed that early discharge was an independent factor that decreased the likelihood of mortality one year following surgery.

Unlike other factors that are difficult to modify during clinical practice (such as age), hospital stay is a modifiable factor that can be improved in clinical practice. It is therefore particularly important to optimise and improve post-surgical hospital stay data of patients with fewer comorbidities undergoing HF surgery.

Following the results of the present study, we believe it is suitable to implement a protocol for early discharge for patients with HF and few comorbidities, starting at the time of admission, so that the necessary means are put in place for these patients to be discharged home with assistance or to medium-stay or rehabilitation centres 4–5 days after the surgical intervention, allowing for a gradual recovery of functionality and independence without the risks associated with admission to an acute care hospital.

Limitations of the studyAmong the limitations, we found that the data collection is based on what is recorded in the clinical history. Thus, automated-computerised data were used for as many variables as possible (e.g., mortality outcome variables and readmission were recorded by dates in the computer programme). Another limitation might be that previous comorbidities such as heart disease, obesity, etc., are collected through the pre-anaesthesia assessment reports, not as independent variables. Nevertheless, the anaesthetic risk scale is a standardised tool for pre- and post-operative risk assessment. Another limitation is that the study included all the reasons why patients could not be discharged early (both because they developed medical problems and logistical problems, etc.). Lastly, despite the fact that we obtained statistically significant results for subjects who were discharged early, further studies would be necessary to demonstrate the possible cause–effect relationship between the variables.

ConclusionsIn the present study of individuals undergoing HF surgery with fewer comorbidities, the early discharge group obtained better results in terms of 30-day and one-year mortality rates following surgery, as well as 30-day hospital readmission for medical causes, when compared to the non-early discharge group.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iii.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.