The increase in life expectancy and the ageing population have led to a higher incidence of hip fractures, especially in women over 60 years old. This study analyzes the influence of a multidisciplinary team with the collaboration of a specialist in internal medicine (IM) with the trauma department on mortality, perioperative complications and hospital stay in patients with hip fractures.

Material and methodsAn analytical observational study of historical cohorts was conducted in patients over 65 years admitted for hip fracture and treated with arthroplasty or intramedullary nailing. Two cohorts were established: one before and one after the IM assignment. Patients with metabolic bone diseases different from osteoporosis and those who were operated in other centres were excluded. The minimum follow-up was 12 months.

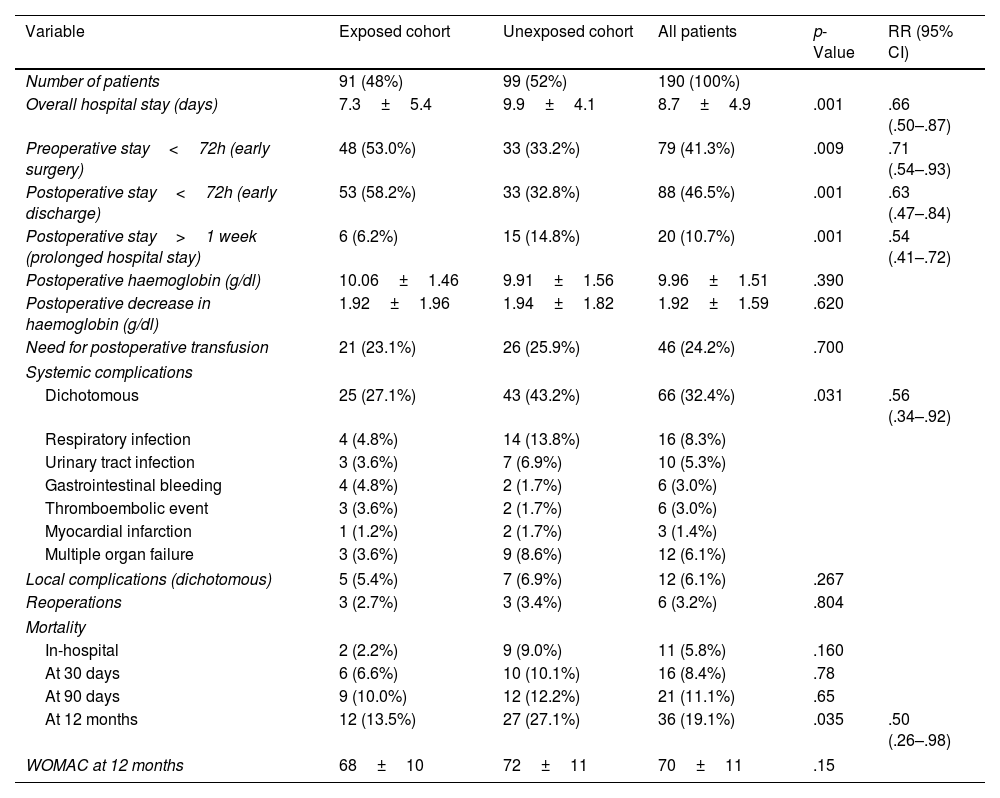

ResultsA total of 190 patients (50 men, 140 women) were included, with a mean age of 82.0 years and a BMI of 27.5. Mortality, which was the main objective of our study, during the first 12 months was higher in the non-IM (27.1 vs. 13.5%; p=.035). In addition, we included systemic complications and hospital stay as secondary objectives. Systemic complications were also higher in the non-IM cohort (43.2 vs. 27.1%; p=.031). Overall hospital stay was shorter in the IM cohort (7.3 vs. 9.9 days; p=.001). “Preoperative stays shorter than 72h were more frequent in the IM group (53.0 vs. 33.2%; p=.009).

ConclusionsMultidisciplinary collaboration with a specialist in internal medicine significantly reduces first-year mortality, systemic complications, and hospital stay in hip fracture patients, allowing earlier interventions and hospital discharge.

El aumento de la esperanza de vida y el envejecimiento de la población han incrementado la incidencia de fracturas de cadera, especialmente en las mujeres mayores de 60 años. Este estudio analiza la influencia de la colaboración multidisciplinar con un médico especialista en medicina interna (MI), en un servicio de traumatología, en la mortalidad, en las complicaciones perioperatorias y en la estancia hospitalaria de los pacientes con fractura de cadera.

Material y métodoSe realizó un estudio observacional analítico de cohortes históricas en los pacientes mayores de 65 años ingresados por fractura de cadera e intervenidos mediante artroplastia o enclavado intramedular. Se establecieron 2 cohortes: una previa a la adscripción del especialista de MI y otra posterior. Se excluyeron a los pacientes con afecciones óseas metabólicas distintas a la osteoporosis y aquellos intervenidos en otros centros. El seguimiento mínimo fue de 12 meses.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 190 pacientes (50 varones y 140 mujeres), con edad media de 82,0 años y un IMC de 27,5. El objetivo primario del estudio fue mortalidad, que durante los primeros 12 meses fue mayor en la cohorte sin especialista en MI (27,1 vs. 13,5%; p=0,035). Además de la mortalidad, también se analizaron como objetivos secundarios las complicaciones sistémicas y la estancia hospitalaria. Las complicaciones sistémicas fueron también mayores en la cohorte sin especialista en MI (43,2 vs. 27,1%; p=0,031). La estancia hospitalaria global fue menor en la cohorte con especialista en MI (7,3 vs. 9,9 días; p=0,001). La estancia preoperatoria inferior a 72h fue más frecuente en el grupo con especialista en MI (53,0 vs. 33,2%; p=0,009).

ConclusionesLa colaboración multidisciplinar con un médico especialista en MI reduce significativamente la mortalidad durante el primer año, las complicaciones sistémicas, y el tiempo de hospitalización en pacientes con fractura de cadera, permitiendo intervenciones y altas hospitalarias más precoces.

Increased life expectancy and the resulting ageing of the population have led to a rise in hip fractures. In Spain, approximately 60,000 hip fractures occur in people over 60 years of age each year, and the incidence is four times higher in women.1 In 1990, there were 1.26 million hip fractures worldwide, and it is estimated that this figure will rise to 4.5 million by 2050, thus constituting a public health problem.2

This type of fracture generally occurs in complex patients, both due to their advanced age and the comorbidities they often present. This leads to an increase in complications and mortality: 5% during hospitalisation, 10% within the first month, and up to 30% within the first year.2

Hip fractures include different types of fractures that can affect both the intracapsular and extracapsular regions, not just fractures of the proximal femur. These include femoral neck, pertrochanteric, and subtrochanteric fractures, each with distinct clinical implications that may require different therapeutic management.3

A number of factors influence the outcome for patients with hip fractures, including non-modifiable factors, such as demographics and comorbidity, as well as modifiable factors. The latter include the introduction of a multidisciplinary approach, with close collaboration between specialists in internal medicine (IM) or geriatrics and orthopaedic surgeons. The first references to this approach appeared in England in 1950, when different models were described, ranging from assigning a regular internist for orthopaedic and trauma surgery (OTS) department consultations to attaching an internist to that department. Despite advances in this area, there remains controversy as to which model is most appropriate.4

The primary objective of this study is to analyse and describe the impact of assigning a specialist in internal medicine (IM) to the OTS service on mortality during the first postoperative year after hip fracture. The secondary objectives were the occurrence of perioperative complications and length of hospital stay.

Material and methodOur study design was an analytical observational study of historical cohorts. The inclusion criteria were patients over 65 years of age admitted to our hospital for hip fracture and who underwent arthroplasty or intramedullary nailing.

Patients with metabolic bone disease other than osteoporosis (e.g. osteomalacia, Paget's disease, or renal osteodystrophy), and those who ultimately underwent surgery at other centres or who were reviewed at their referral hospitals after surgery at our centre, were excluded as this would make appropriate follow-up impossible.

The change in management with the assignment of an IM specialist to the trauma department was implemented in January 2018 as part of an institutional effort to improve outcomes in patients with hip fractures. This intervention was adopted progressively to optimise multidisciplinary care at our centre.

Two non-concurrent cohorts were established: one cohort prior to assigning the IM specialist to the OTS service (unexposed cohort) and another cohort after the assignment of the IM specialist to the OTS service (exposed cohort). With regard to the multidisciplinary team, it should be noted that only one IM specialist was involved in the management of patients throughout the study period. This professional was permanently assigned to the trauma service to treat these patients with hip fractures.

Surgical procedureAll patients received preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis in the form of 2g of cefazolin, unless contraindicated due to allergy, in which case 1g of vancomycin was used instead. The procedure was performed under spinal anaesthesia unless contraindicated; in these cases, general anaesthesia was used.

For all arthroplasty patients, a Hardinge lateral approach was used. Patients undergoing hemiarthroplasty received a monopolar head with a cemented Avenir® stem (Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, Indiana, USA) of the composite beam type and self-locking design. For total arthroplasty, a cemented Avenir® stem was implanted with an uncemented Pinnacle acetabular cup (Depuy®). Where osteosynthesis with cephalomedullary nailing was performed, Gamma3 and Gamma Long nails (Stryker®) were used.

All the surgical procedures were performed by experienced surgeons, defined as those with over 10 years’ experience in hip fracture surgery who have performed over 50 hip arthroplasties (both partial and total) throughout their professional career.5 In some cases, resident surgeons participated under the direct supervision of the lead surgeon.

Paracetamol and intravenous metamizole were administered for postoperative analgesia. In addition, antithrombotic prophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin was administered in all cases, and a rehabilitation protocol was followed. This protocol was similar in both groups and involved resuming walking from the day after surgery.

Study variablesIndependent variables were collected in both cohorts at admission and during hospitalisation. At admission, the following variables were collected: demographic data; substance use; associated comorbidities; the Charlson comorbidity index,6 the Barthel index,7 previous hip fracture; outlier patient admission; fracture type; laterality; and baseline analytical parameters. During hospitalisation, variables such as blood count, coagulation, biochemistry, renal function, hepatic function, and respiratory function were recorded, as well as variables related to the surgical procedure.

The following outcome variables were recorded: preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative complications (both in-hospital and out-of-hospital). These included local complications (periprosthetic/peri-implant fractures, infection, dislocation, aseptic loosening, gluteal insufficiency, limb length discrepancy, pseudoarthrosis, or neurovascular injuries) and systemic complications (anaemia, deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary thromboembolism, urinary and respiratory infection, ischaemic heart disease, confusional syndrome, gastrointestinal bleeding, and multiple organ failure). In addition, reoperation rates and mortality (in-hospital, at 30 days, 90 days, and 12 months) were recorded. The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis (WOMAC) score was also recorded at 12 months. Data were collected on admission, during the hospital stay and at follow-up visits at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year postoperatively.

Data were collected upon admission, during the hospital stay, and at follow-up visits at 1 month, 3 months, and 1 year postoperatively.

Statistical analysisData were recorded in a Microsoft Access® (18.0, Office 2021) database and analysed using IBM SPSS® statistical analysis software (version 25).

Quantitative variables were expressed as the arithmetic mean and median as measures of central tendency, while standard deviation and interquartile range were used as measures of dispersion. Qualitative variables were presented as frequencies and percentages.

Pearson's χ2 test was used for the statistical analysis of qualitative variables. For quantitative variables, after verifying that they did not follow a normal distribution using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, the Mann–Whitney U test was applied. Differences were considered statistically significant when the p-value was less than .05.

The magnitude of the effect between the main exposure variable and the different outcome variables was described by calculating the different relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

ResultsA total of 190 patients (50 males, 140 females) were available for final analysis, with a mean age of 82.0 years±11.7, ranging from 65 to 95 years, and a mean BMI of 27.5±6.2 (Table 1).

Independent variables.

| Variable | Exposed cohort | Unexposed cohort | All patients | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 91 (48%) | 99 (52%) | 190 (100%) | |

| Age (in years) | 81.5±13.9 (65–95) | 83.0±9.1 (67–93) | 82.0±11.7 (65–95) | .088 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 22 (24.2%) | 28 (28.3%) | 50 (26.3%) | .088 |

| Female | 69 (75.8%) | 71 (71.7%) | 140 (73.7%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.2±4.1 | 28.1±7.1 | 27.5±6.2 | .092 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 5.23±2.83 | 5.46±1.44 | 5.43±2.29 | .184 |

| Barthel index | 72.5±18.3 | 70.8±19.1 | 71.6±18.7 | .62 |

| Main comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 50 (54.9%) | 51 (51.5%) | 101 (53.2%) | .34 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 15 (16.5%) | 15 (15.3%) | 30 (15.8%) | .41 |

| Heart failure | 8 (8.8%) | 9 (9.6%) | 17 (8.9%) | .39 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 5 (5.5%) | 6 (6.1%) | 11 (5.8%) | .56 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 7 (7.7%) | 5 (5.0%) | 12 (6.3%) | .52 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 20 (22.0%) | 23 (23.3%) | 43 (22.6%) | .47 |

| Chronic kidney failure | 11 (12.1%) | 13 (13.5%) | 24 (12.6%) | .50 |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 9 (10.0%) | 10 (10.3%) | 19 (10.2%) | .63 |

| Previous hip fracture | 15 (16.7%) | 17 (18.9%) | 32 (17.8%) | .72 |

| Outlier patient admission | 14 (15.4%) | 15 (15.2%) | 29 (15.3%) | .192 |

| Type of fracture | ||||

| Neck of femur | 35 (38.5%) | 37 (37.4%) | 72 (37.9%) | .256 |

| Trochanteric | ||||

| Pertrochanteric | 42 (46.2%) | 49 (49.5%) | 91 (47.9%) | |

| Subtrochanteric | 14 (15.3%) | 13 (13.1%) | 27 (14.2%) | |

| Laterality | ||||

| Right | 52 (57.1%) | 57 (57.6%) | 109 (57.4%) | .326 |

| Left | 39 (42.9%) | 42 (42.4%) | 81 (42.6%) | |

| Type of procedure | ||||

| HA | 23 (25.3%) | 24 (24.2%) | 47 (24.7%) | .092 |

| THR | 12 (13.2%) | 13 (13.1%) | 25 (13.2%) | |

| Short nail | 42 (46.2%) | 49 (49.5%) | 91 (47.9%) | |

| Long nail | 14 (15.3%) | 13 (13.2%) | 27 (14.2%) | |

BMI: body mass index; HA: hemiarthroplasty; THR: total hip replacement.

Losses to follow-up were recorded in 15 patients, distributed between the exposed cohort (7 patients) and the unexposed cohort (8 patients). The main reasons for these losses were changes of residence outside the study area or loss of contact at scheduled follow-up visits. These losses did not significantly affect the comparability between the cohorts or the main results of the study, and were not included in the final analysis. Overall, the unexposed cohort comprised 99 patients who received treatment and follow-up solely from the OTS service, while the exposed cohort consisted of 91 patients who received joint follow-up from the OTS service and the IM specialist during their hospitalisation. The minimum follow-up period was set at 12 months.

In order to assess the homogeneity of both cohorts, a subgroup analysis was performed with respect to the variables age (p=.088), sex (p=.088), BMI (p=.092), Charlson comorbidity index (p=.184), Barthel index (p=.62), type of fracture (p=.256), and procedure (p=.092), without finding statistically significant differences. Therefore, it can be concluded that both groups had a homogeneous distribution with respect to the variables and are therefore comparable groups (Table 1).

Similarly, the main comorbidities at the time of admission were documented in both cohorts, including cardiovascular disease (hypertension, ischaemic heart disease, and heart failure), a history of thromboembolism (deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism), diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, and respiratory disease. The cohort that received multidisciplinary follow-up had a slightly higher prevalence of hypertension (54.9% vs. 51.5%), though this difference was not statistically significant (p=.34). There were no significant differences between the cohorts in terms of the incidence of previous thromboembolic disease (13.2% vs. 11.1%; p=.57) or other recorded comorbidities (Table 1).

A total of 72 intracapsular femoral neck fractures and 118 trochanteric fractures (91 pertrochanteric and 27 subtrochanteric) were included. No statistically significant differences in morbidity and mortality were found according to fracture type (subcapital vs. pertrochanteric; p=.68). Of the 72 femoral neck fractures, 47 were treated with partial arthroplasty, and 25 with total arthroplasty. Trochanteric fractures were treated with short intramedullary nailing in 91 cases and long intramedullary nailing in 27 cases (Table 1).

The overall hospital stay was significantly shorter in the exposed cohort (7.3±5.4 vs. 9.9±4.1 days; p=.001). During the analysis, it was observed that a preoperative stay of less than 72hours was significantly more frequent in the exposed group (53.0 vs. 33.2%; p=.009). In other words, the group that was followed up by the IM specialist underwent surgery earlier (Table 2).

Dependent variables.

| Variable | Exposed cohort | Unexposed cohort | All patients | p-Value | RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 91 (48%) | 99 (52%) | 190 (100%) | ||

| Overall hospital stay (days) | 7.3±5.4 | 9.9±4.1 | 8.7±4.9 | .001 | .66 (.50–.87) |

| Preoperative stay<72h (early surgery) | 48 (53.0%) | 33 (33.2%) | 79 (41.3%) | .009 | .71 (.54–.93) |

| Postoperative stay<72h (early discharge) | 53 (58.2%) | 33 (32.8%) | 88 (46.5%) | .001 | .63 (.47–.84) |

| Postoperative stay>1 week (prolonged hospital stay) | 6 (6.2%) | 15 (14.8%) | 20 (10.7%) | .001 | .54 (.41–.72) |

| Postoperative haemoglobin (g/dl) | 10.06±1.46 | 9.91±1.56 | 9.96±1.51 | .390 | |

| Postoperative decrease in haemoglobin (g/dl) | 1.92±1.96 | 1.94±1.82 | 1.92±1.59 | .620 | |

| Need for postoperative transfusion | 21 (23.1%) | 26 (25.9%) | 46 (24.2%) | .700 | |

| Systemic complications | |||||

| Dichotomous | 25 (27.1%) | 43 (43.2%) | 66 (32.4%) | .031 | .56 (.34–.92) |

| Respiratory infection | 4 (4.8%) | 14 (13.8%) | 16 (8.3%) | ||

| Urinary tract infection | 3 (3.6%) | 7 (6.9%) | 10 (5.3%) | ||

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 4 (4.8%) | 2 (1.7%) | 6 (3.0%) | ||

| Thromboembolic event | 3 (3.6%) | 2 (1.7%) | 6 (3.0%) | ||

| Myocardial infarction | 1 (1.2%) | 2 (1.7%) | 3 (1.4%) | ||

| Multiple organ failure | 3 (3.6%) | 9 (8.6%) | 12 (6.1%) | ||

| Local complications (dichotomous) | 5 (5.4%) | 7 (6.9%) | 12 (6.1%) | .267 | |

| Reoperations | 3 (2.7%) | 3 (3.4%) | 6 (3.2%) | .804 | |

| Mortality | |||||

| In-hospital | 2 (2.2%) | 9 (9.0%) | 11 (5.8%) | .160 | |

| At 30 days | 6 (6.6%) | 10 (10.1%) | 16 (8.4%) | .78 | |

| At 90 days | 9 (10.0%) | 12 (12.2%) | 21 (11.1%) | .65 | |

| At 12 months | 12 (13.5%) | 27 (27.1%) | 36 (19.1%) | .035 | .50 (.26–.98) |

| WOMAC at 12 months | 68±10 | 72±11 | 70±11 | .15 | |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; RR: relative risk.

Considering a postoperative hospital stay of less than 72h as early discharge, it was found that discharge within this period was significantly higher in the exposed group (58.2% vs. 32.8%; p=.001). Finally, establishing prolonged hospital stay as a postoperative stay of more than one week, this was significantly higher in the group not treated by the IM specialist (14.8 vs. 6.2%; p=.001) (Table 2).

During the analysis, it was found that mortality within the first 12 months was significantly higher in the unexposed cohort (27.1 vs. 13.5%; p=.035). However, in-hospital mortality (2.2 vs. 9.0%; p=.56), at 30 days (6.6 vs. 10.1%; p=.78), and at 90 days (10.0 vs. 12.2%; p=.65) did not show significant differences between the groups. Systemic complications were significantly higher in the unexposed cohort (43.2 vs. 27.1%; p=.031) (Table 2). Patients who developed more postoperative medical complications had a higher number of comorbidities. The Charlson index was significantly higher in these patients than in those who did not present complications (6.1±2.5 vs. 4.3±1.8; p=.02), indicating an association between previous health status and the incidence of systemic complications.

Following discharge, 78% of patients returned to their previous home and 22% to nursing homes. In the exposed cohort, 79% returned home and 21% to nursing homes, while in the unexposed cohort these percentages were 77% and 23%, respectively, with no significant differences (p=.67). The destination and functional status prior to the fracture, as measured by the Barthel Index, had no significant influence on morbidity and mortality (p=.54 and p=.62, respectively).

It was also recorded whether patients had previously suffered hip fractures. Fifteen percent of patients in the exposed cohort and 17% in the unexposed cohort had a history of fracture, with no significant difference between the two groups (p=.72) (Table 1). This factor also had no significant influence on morbidity and mortality (p=.59).

Other outcome variables were also analysed, such as local complications, anaemia and the need for postoperative transfusion, reoperation rate and in-hospital mortality, with no statistically significant differences (p>.05) (Table 2).

The WOMAC index was also analysed 12 months postoperatively and the exposed cohort had a more favourable score than the unexposed cohort. However, this difference was not statistically significant (68±10 vs. 72±11; p=.15) (Table 2).

For the variables that were statistically significant, the effect size between the main exposure variable and the outcome variables was calculated, as shown in Table 2. An RR of .56 (95% CI: .34–.92; p=.018) was obtained for systemic complications and an RR of .50 for mortality during the first year (95% CI: .256–.98; p=.035).

The RR was also calculated for early surgery (first 72h), early discharge (72h postoperatively), and prolonged hospitalisation (>1 week), as shown in Table 2.

DiscussionOur study reveals that assigning an internist to the trauma service for the joint management of patients with hip fractures leads to reduced mortality during the first year, fewer systemic complications, shorter time to surgery, and shorter postoperative hospital stay until discharge. The findings of this study are consistent with the current literature on reducing mortality during the first postoperative year. The meta-analysis published by Van Heghe et al.4 shows a 14% reduction in mortality at one year in patients with joint follow-up, which is similar to the reduction obtained in our study (13.6%). We believe that early surgical intervention within the multidisciplinary collaboration group was pivotal in reducing systemic complications and mortality, as it enabled the early optimisation of the patient's general condition.

The available literature consistently shows a marked reduction in mortality during the first year,8 with figures reaching 4% in some studies.9 In our study, however, no statistically significant difference was observed in hospital mortality, a finding similar to that of Wagner et al.10 While statistical significance was not achieved, there was a notable reduction in in-hospital mortality in the exposed cohort (9% in the unexposed cohort vs. 2.2% in the exposed cohort). Statistically significant differences were observed in the meta-analysis published by Van Heghe et al.,4 which reported a 28% reduction in in-hospital mortality.

After hospitalisation, mortality was similar in both groups, both one month and three months after surgery, with no significant differences observed until one year after surgery. At this point, statistically significant differences were observed (27.1% in the unexposed group vs. 13.5% in the exposed group; p=.035).

In our study, a notable reduction in systemic complications was observed (16.1% decrease in the exposed cohort), with respiratory and urinary infections being the most frequently avoided followed by gastrointestinal bleeding, thromboembolic events, myocardial infarction, and multiple organ failure. These results are consistent with the cohort study published by Schuijt et al.8 with a decrease in systemic complications from 48% to 42%, p<.05, which mainly included, as in our study, respiratory and urinary tract infections and thromboembolic events.

There is controversy in the published literature regarding time to surgery. In our study, we defined early surgery as that performed within the first 72h. We observed that after implementing the multidisciplinary team with the IM specialist assigned to the OTS service, 53% of patients underwent early surgery, compared to only 33% previously. These findings are consistent with those reported by other authors.11,12 In line with these data, the study by Mesa-Lampré et al.13 observed a mean time to surgery of 2.57 days, which falls within the 72-h range considered early in our study. The same is true of the analysis by Fernández-Ibañez et al.,14 where the average time to surgery was 48h, and Chavarro-Carvajal et al.,15 with an average time to surgery of 55h. Similarly, the study by Nijmeijer et al.16 found that, after 10 years of implementation of their unit, although a delay in surgery beyond the first 24h was observed, probably due to patient optimisation, it remained within the first 48h after admission and could also be considered early surgery.

However, other publications, such as the meta-analysis by Van Heghe et al.4 and the study by Solberg et al.17 found no statistically significant differences in the timing of surgery. Therefore, there is no consensus on whether patients under joint management undergo surgery earlier or not.

In the literature reviewed, only one study found no significant differences in overall length of hospital stay.17 In contrast, our study's findings are consistent with numerous publications12,16,18 that report a significant reduction in length of hospital stay (an average reduction of 2.5 days). This enabled 58% of patients followed up by the IM specialist assigned to the OTS service to be discharged within the first 72h postoperatively, compared with 33% of the control group. While there is no consensus among different studies regarding the number of days by which hospital stay could be reduced, which varies between 1.5 and 7 days, our findings are similar to those published by Van Heghe et al.4 in their meta-analysis (1.55 days). Solberg et al.17 add that this effect is not affected by different models of orthogeriatric units (integrated care vs. on-demand consultative services).

In our study, we found no statistically significant differences in anaemia or the postoperative transfusion rate. However, Balvis-Balvis et al.9 describe an increase in transfusion rate from 27% to 53% after the implementation of an orthogeriatric unit. This could be explained by the transfusion indication being adjusted based more on the patient's individual comorbidities than on strictly analytical parameters alone.

According to our calculations of the magnitude of the effect, follow-up by an IM specialist assigned to the OTS service would act as a protective factor against mortality in the first year (RR: .50), systemic complications (.56), early surgery (RR: .71), hospital discharge within the first 72h (RR: .63), and hospital stay of longer than one week (0.54). These findings are consistent with those published by Schuijt et al.8 with an OR: .66 (95% CI: .45–.96; p=.029) for mortality during the first year and an OR: .65 (95% CI: .47–.91; p=.011) for systemic complications.

Finally, as Solberg et al.17 indicate, the most effective orthogeriatric care method remains unclear, although integrated and shared care are believed to offer better results than on-demand consultation services.

In terms of functionality, our results suggest that, although multidisciplinary collaboration with an internist during hospitalisation showed a trend towards better function at 12 months, according to the WOMAC index, the difference observed was not statistically significant. Previous studies, such as that by Tseng et al.,19 have reported that multidisciplinary intervention can improve functional recovery in patients with hip fractures. In our study, multidisciplinary collaboration combining the support of the IM specialist and other specialists contributed to more favourable functional recovery.

Potential biases, and possible impact on the estimates made were considered while conducting this study. In order to mitigate information bias, data were collected identically in both cohorts, and the observer/investigator was kept blind to the exposure variable (whether or not the patient was followed up by the IM specialist).

Losses to follow-up were documented and analysed for independence from the exposure variable and were not included in the final analysis.

The limitations of this study include the small sample size and its retrospective nature. Nevertheless, our main results achieved statistical significance and are consistent with the findings published by different authors in the currently available literature.

ConclusionsAssigning an internist to the trauma service has been shown to significantly reduce systemic complications and mortality in patients admitted for surgical treatment for hip fractures in the first year.

This collaboration optimises the management of comorbidities, favouring earlier surgical interventions, which are decisive for the prognosis of these patients.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iii.

AuthorshipAll signatories contributed to the design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and the writing and review of the final manuscript.

Ethical responsibilitiesIn undertaking this study, the ethical principles set out in the Declaration of Helsinki, as last revised in Fortaleza, Brazil, in 2013, were strictly adhered to. The Provincial Research Ethics Committee of Malaga (30/07/2020) considered this study to be ethically and methodologically sound.

FundingNo specific support from public sector agencies, commercial sector, or not-for-profit organisations was received for this research study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.