Hip fracture is a frequent orthopaedic emergency which associates high morbidity and mortality and intense pain. Locoregional analgo-anaesthetic techniques, both central and peripheral, occupy a preferential place in the multimodal therapeutic arsenal. Recently, a new regional blockade has emerged, the pericapsular block or PENG block (PEricapsular Nerve Group).

The objective is to evaluate in patients with hip fracture, the antinociceptive efficacy of the preoperative PENG block, residual motor block and time for postoperative functional recovery.

Method and materialsProspective descriptive observational study with patients going to have total hip arthroplasty. PENG block was performed before surgery. Pain was assessed with the Visual Numerical Scale (VNS) before the blockade, 30min later, in the immediate postoperative period and 24h after the intervention. Motor block according to the Bromage scale and time needed for assisted walking were also evaluated.

ResultsPENG block provided effective analgesia in all patients, with a decrease in at least 3 points on the VNS at every step in which it was evaluated. The average difference between pain before and after the block was 7.5 points on the VNS. It allowed the transfer and placement of the patient without haemodynamic alteration, exacerbation of pain or other complications.

ConclusionsPENG block is an effective and safe regional analgesic technique for patients with hip fracture. It allows mobilisation and placement before surgery without pain exacerbation, promoting early mobility and rehabilitation.

La fractura de cadera es una emergencia ortopédica frecuente que asocia elevada morbimortalidad y dolor intenso. Las técnicas analgo-anestésicas locorregionales, tanto centrales como periféricas, ocupan un lugar preferente dentro del arsenal terapéutico multimodal. A los bloqueos clásicos se ha sumado recientemente el bloqueo pericapsular, o PENG (PEricapsular Nerve Group).

El objetivo es evaluar en pacientes con fractura de cadera la eficacia antinociceptiva del bloqueo PENG preoperatorio, el bloqueo motor residual y el tiempo necesario para la recuperación funcional postoperatoria.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional descriptivo prospectivo en pacientes programados para artroplastia total de cadera. El bloqueo PENG se realizó previo a la cirugía. Se evaluó el dolor con escala visual numérica (EVN) antes de la realización del bloqueo, 30min después, en el postoperatorio inmediato y a las 24h de la intervención, el grado de bloqueo motor según la escala de Bromage y el tiempo necesario para la deambulación asistida.

ResultadosEn todos los pacientes el bloqueo PENG proporcionó analgesia eficaz. Logró disminuir 3 o más puntos la EVN en todos los momentos evaluados. La diferencia media entre el dolor previo y posterior al bloqueo fue de 7,5 puntos en la EVN, lo que permitió el traslado y la colocación del paciente sin alteración hemodinámica, exacerbación del dolor, ni otras complicaciones.

ConclusionesEl bloqueo PENG es una técnica analgésica regional efectiva y segura para pacientes con fractura de cadera; facilita la movilización y la colocación previa a la cirugía sin exacerbación del dolor, y favorece una temprana movilidad y rehabilitación.

- •

PENG (PEricapsular Nerve Group) block is an effective analgesic technique for hip fractures.

- •

It provides a total blockade of the peripheral nerves from the lumbar plexus responsible for nociception of the femoral capsule.

- •

It does not block the femoral nerve, and therefore there is little motor involvement, which promotes mobility and full recovery.

The incidence of hip fracture ranges between 40,000 and 45,000 per year in Spain.1 It is a frequent orthopaedic emergency in patients over 65 years of age.2,3 Incidence rates by sex in 2010 were 325.30/100,000 inhabitants/year in males and 766.37/100,000 inhabitants/year in females.4 However, the number of cases has been rising in recent years, and is expected to increase further,1 given the increased life expectancy of the population.

This pathology is associated with high morbidity and mortality and severe pain, which requires the early use of effective analgesic techniques, especially in elderly patients, as poorly controlled pain is associated with increased risk of delirium, long hospital stays, poorer quality of life, and acute and chronic postoperative pain.2 Traditional analgesic treatment has been based on the use of drugs (anti-inflammatory, adjuvants, and opioids) with associated side and adverse effects.3

Locoregional analgesic and anaesthetic techniques are frequently used in the perioperative management of these fractures, as they offer better and longer-lasting analgesia than other systemic techniques, and less opiate consumption, with a reduction in their undesirable effects, especially in chronic or multi-pathological patients.5 They enable early discharge, increase patient satisfaction and, eventually, reduce healthcare costs.3

The recent development in ultrasound, together with the deepening of anatomical knowledge, has facilitated new analgesic/anaesthetic approaches to hip fractures. The traditional analgesic blocks (lumbar plexus block, femoral nerve block, sciatic nerve block, 3-in-1 block, iliac fascia block) are partial, as they do not affect all the sensory nerves that innervate the joint, and cause prolonged motor block, thus increasing the time required for recovery. Capsular blocks (iliopsoas plane block and pericapsular nerve block, or PENG block) achieve optimal analgesia without compromising motor function.6

Pericapsular nerve block, or PENG (PEricapsular Nerve Group),3 allows analgesia and ideal positioning of the patient for puncture for spinal anaesthesia in femoral fractures.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the analgesic effectiveness of PENG block in patients with subcapital and basicervical femur fractures. Pain intensity was measured before and after PENG block, after recovery from the motor block caused by spinal anaesthesia, and 24h after surgery.

Material and methodsProspective descriptive observational study in patients with subcapital or basicervical fracture of the femur, of oncological cause, scheduled for total hip arthroplasty at the Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid and who agreed and signed their informed consent to undergo the technique and participate in the study. The study was approved by the CEIC of the HCUV on 19 September 2019 and code PI 19-1474.

Patients were included with pathological femur fractures, scheduled for total hip arthroplasty, over 18 years of age, with ASA score between I and III, sufficient cognitive capacity to assess pain intensity using the 11-item visual numeric scale (VNS), where 0 is the absence of pain and 10 the maximum intensity that can be endured, and having provided signed consent both to undergo the procedure and to record and publish their data.

Patients who did not meet the inclusion criteria, or with diseases that contraindicated the procedure, such as allergy to local anaesthetics, localised infection at the puncture site, or anticoagulant or antiplatelet treatment, were excluded from the study.

Once the patient was informed and after obtaining their consent to undergo the procedure, they were placed in the supine decubitus position, a peripheral venous line was cannulated in the upper limb contralateral to the fracture and monitored with pulse oximetry, electrocardiogram, and non-invasive blood pressure. The procedure did not delay the surgical reduction of the fracture, which was performed as quickly as possible.

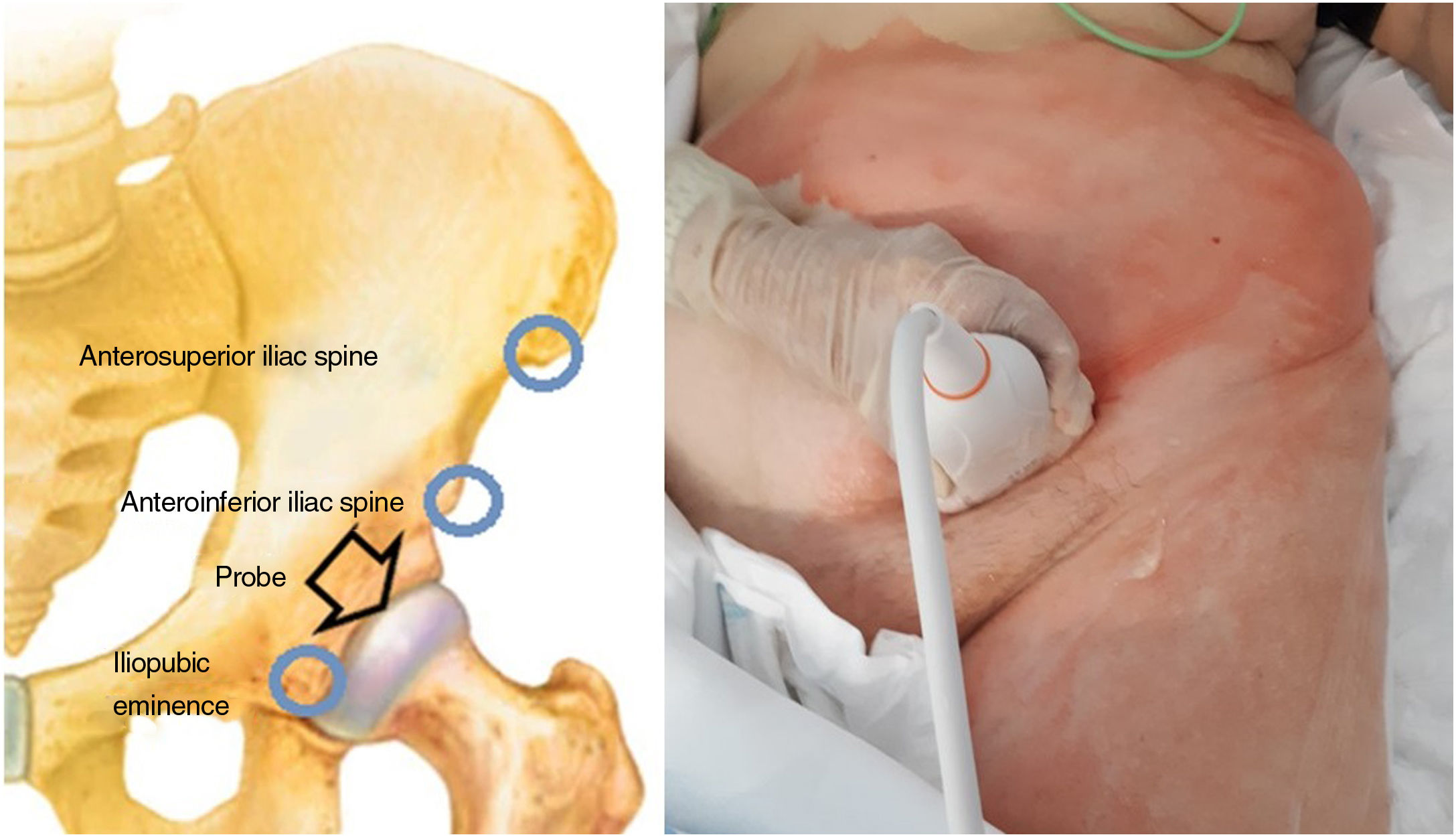

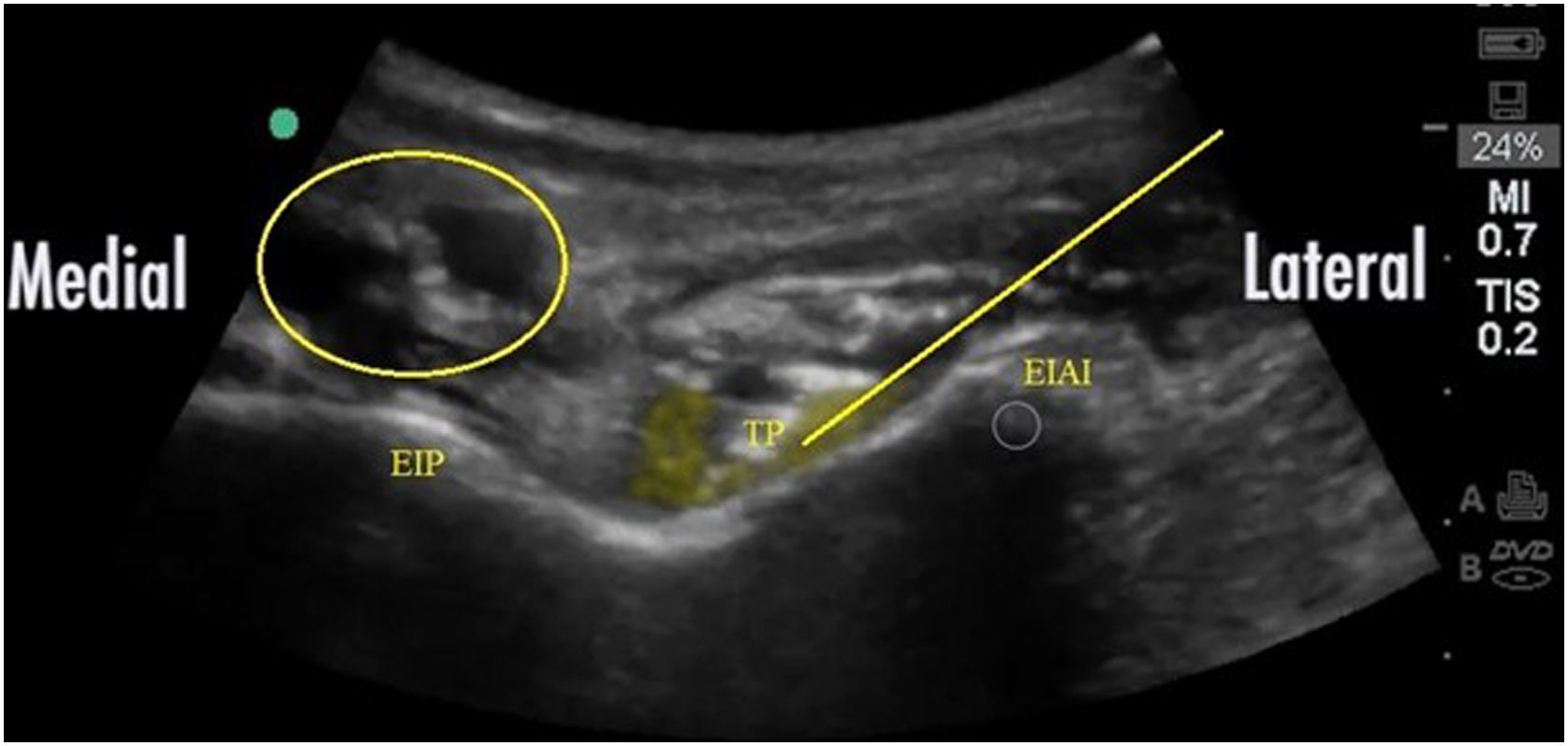

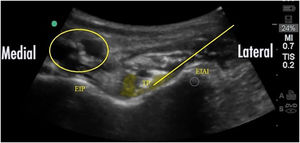

After applying the usual aseptic measures in the blockade field, ultrasound scanning was performed (Mindray Diagnostic Ultrasound System Model Z6) using a low frequency convex ultrasound probe (2.5-mHz), or a high frequency linear ultrasound probe (6–13mHz) for patients with little adipose tissue. The transducer was located in the plane transverse to the anteroinferior iliac spine until it was located by ultrasound, then rotated 45° until it was aligned with the iliopectineal eminence (Fig. 1) to obtain the image in Fig. 2, where the following structures were visualised: the anteroinferior iliac spine, the iliopectineal eminence, the iliopsoas muscle and tendon, and the femoral artery, vein, and nerves.

An AKUS 21G X 90mm ultrasound needle was inserted in plane, from lateral to medial, avoiding the femoral nerve and vessels, until the tip of the needle was inserted under the psoas tendon. Once in that position, and after negative suction, ropivacaine .1% was injected, in increments of 5ml, up to a total volume of 15–20ml, while observing the spread of the local anaesthetic around the psoas tendon (Fig. 2).

Pain intensity was assessed periodically. All cases received an intravenous analgesic regimen with paracetamol 1g every 6h. The usual chronic opioid treatment was maintained. Repeat analgesic blockade was not necessary in any of the cases. At the time of surgery, spinal anaesthesia was delivered in lateral decubitus, with the fractured limb in an inclined position, with 12mg of bupivacaine, .5% hyperbaric+20μg fentanyl.

Surgery consisted of long stem arthroplasty and cementation.

After recovery following motor block (Bromage scale 0–1), the analgesic regimen was maintained with intravenous paracetamol 1g every 6h. In case of a VNS greater than 3, rescue analgesic therapy was prescribed with metamizole 2g intravenously, and if this was not sufficient, morphine chloride in boluses of 2mg intravenously.

Data were collected on profile (age, sex, etc.), type of primary tumour, type of fracture, anaesthetic risk according to the ASA, anaesthetic-surgical technique, drugs used, and time between the PENG block and surgery.

Pain intensity was assessed at rest, using a VNS and categorical scale (mild, moderate, or severe), and was recorded by the nursing staff of the post-anaesthesia recovery unit and the trauma ward, at four points in time: before the block was performed; 30min after it was performed; after surgery; once the effect of spinal anaesthesia had worn off; and 24h after the intervention.

The grade of motor block using the Bromage scale (4 grades, where 0 corresponds to no motor block, with full flexion of knees and feet, and grade 3 corresponds to complete motor block, with inability to mobilise feet and knees), patient satisfaction and that of the professionals according to a five-item categorical scale (very good, good, normal, poor, or very poor). Complications attributable to the block (nausea, vomiting, haematoma, or puncture site infection) were also recorded.

Data were entered into an Excel® database (Microsoft Office, Microsoft, USA) and analysed with IBM SPSS Statistics version 24.0 for Windows.

A descriptive study was made of the variables analysed. Quantitative variables were presented as mean, median, and standard deviation, maximum and minimum values, and 25th and 75th percentiles. Qualitative variables were presented according to their frequency distribution.

The association of qualitative variables was analysed using Pearson's χ2 test. In the event that the number of cells with expected values less than 5 was greater than 20%, Fisher's exact test was used, or the likelihood ratio test for variables with more than two categories.

Comparisons of quantitative values according to groups were performed with the Kruskal–Wallis test for independent samples.

Comparisons of the different time points assessed for pain were made using the non-parametric Friedman test.

P-values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

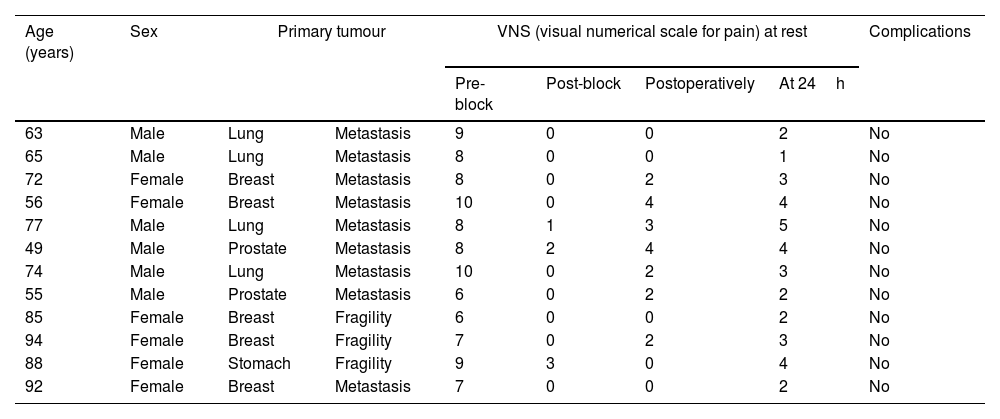

ResultsA total of 12 oncology patients were included in the study with the following characteristics: mean age 72.5 years (6 males and 6 females); the primary tumour was lung in 4 patients, breast in 5, prostate in 2, and stomach in one participant. There were pathological fractures over metastases in 9 of the patients, and in the remaining 3 there were fragility fractures in patients with an active tumour (Table 1).

Patients included in the study, profile, and pathology data. Pain experienced at rest, according to VNS, prior to performing the block, 30min after performing the block, immediately postoperatively and 24h after the intervention.

| Age (years) | Sex | Primary tumour | VNS (visual numerical scale for pain) at rest | Complications | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-block | Post-block | Postoperatively | At 24h | |||||

| 63 | Male | Lung | Metastasis | 9 | 0 | 0 | 2 | No |

| 65 | Male | Lung | Metastasis | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | No |

| 72 | Female | Breast | Metastasis | 8 | 0 | 2 | 3 | No |

| 56 | Female | Breast | Metastasis | 10 | 0 | 4 | 4 | No |

| 77 | Male | Lung | Metastasis | 8 | 1 | 3 | 5 | No |

| 49 | Male | Prostate | Metastasis | 8 | 2 | 4 | 4 | No |

| 74 | Male | Lung | Metastasis | 10 | 0 | 2 | 3 | No |

| 55 | Male | Prostate | Metastasis | 6 | 0 | 2 | 2 | No |

| 85 | Female | Breast | Fragility | 6 | 0 | 0 | 2 | No |

| 94 | Female | Breast | Fragility | 7 | 0 | 2 | 3 | No |

| 88 | Female | Stomach | Fragility | 9 | 3 | 0 | 4 | No |

| 92 | Female | Breast | Metastasis | 7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | No |

The average time taken for the anaesthetic procedure was 30min (including monitoring, analgesic block, and intradural anaesthesia). The surgical time (between incision and the last point of skin closure) was 105±35min.

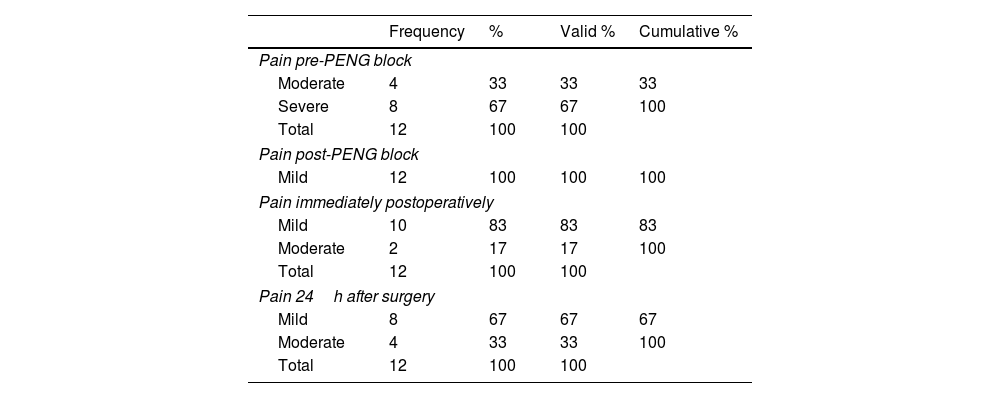

Prior to the PENG block, the patients had moderate (33%) or severe (67%) pain. None had mild pain or no pain (Table 3). The mean VNS score was 8 (Table 2).

Categorisation of pain, pre-and post-PENG block, in the immediate postoperative period, and at 24h.

| Frequency | % | Valid % | Cumulative % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain pre-PENG block | ||||

| Moderate | 4 | 33 | 33 | 33 |

| Severe | 8 | 67 | 67 | 100 |

| Total | 12 | 100 | 100 | |

| Pain post-PENG block | ||||

| Mild | 12 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Pain immediately postoperatively | ||||

| Mild | 10 | 83 | 83 | 83 |

| Moderate | 2 | 17 | 17 | 100 |

| Total | 12 | 100 | 100 | |

| Pain 24h after surgery | ||||

| Mild | 8 | 67 | 67 | 67 |

| Moderate | 4 | 33 | 33 | 100 |

| Total | 12 | 100 | 100 | |

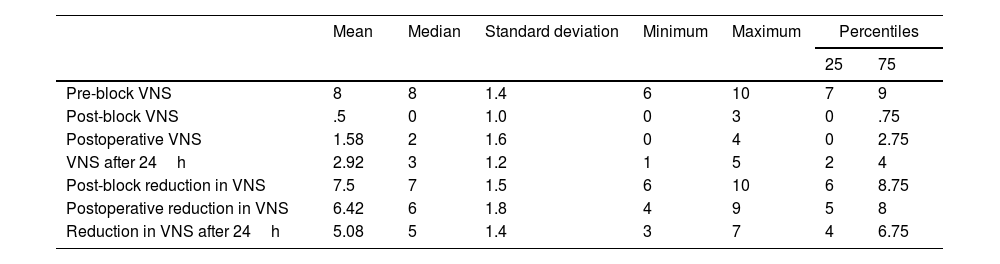

Descriptive statistical study of the variables: pain experienced according to the VNS prior to performing the block, 30 afterwards, immediately postoperatively, and 24h after the intervention. Difference in VNS score between pain pre-block and at three time points; 30min after the PENG block, immediately postoperatively and 24h after the intervention.

| Mean | Median | Standard deviation | Minimum | Maximum | Percentiles | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 75 | ||||||

| Pre-block VNS | 8 | 8 | 1.4 | 6 | 10 | 7 | 9 |

| Post-block VNS | .5 | 0 | 1.0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | .75 |

| Postoperative VNS | 1.58 | 2 | 1.6 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2.75 |

| VNS after 24h | 2.92 | 3 | 1.2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 4 |

| Post-block reduction in VNS | 7.5 | 7 | 1.5 | 6 | 10 | 6 | 8.75 |

| Postoperative reduction in VNS | 6.42 | 6 | 1.8 | 4 | 9 | 5 | 8 |

| Reduction in VNS after 24h | 5.08 | 5 | 1.4 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 6.75 |

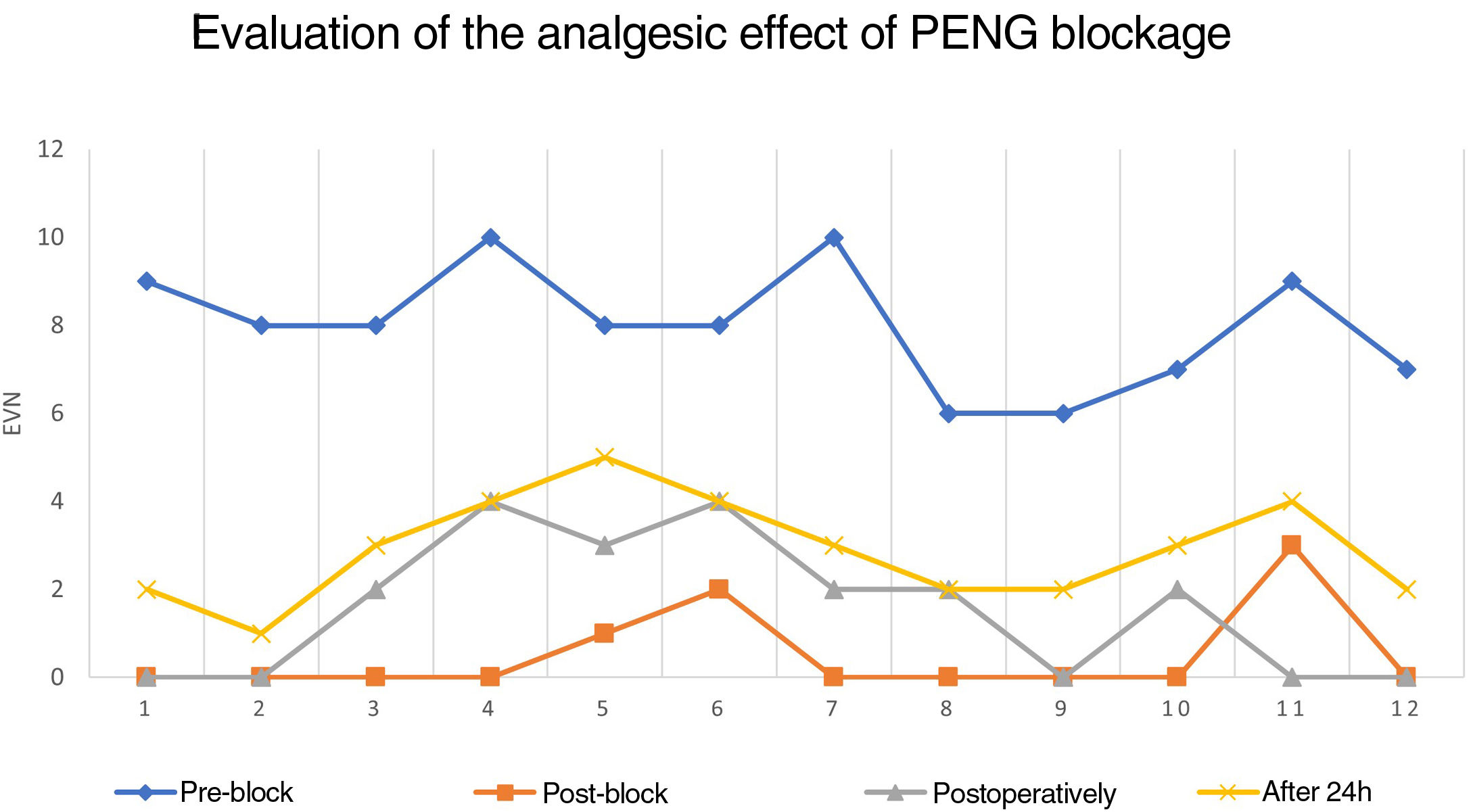

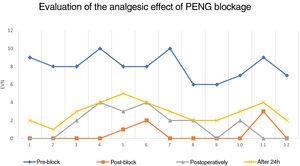

At 30min following the PENG block, no patient had severe or moderate pain, but all patients had mild pain (Table 3), of which 9 patients had no pain at all (Table 1), representing 75% of patients with a VNS=0 out of the total. The mean VNS score at this time was .5, with a mean difference of 7.5 points between pain pre- and post-blockade (Table 2).

No severe pain was noted in any patient over the 24h after surgery. In the immediate postoperative period, no patient had severe pain, 2 patients (17%) had moderate pain, and 10 patients (83%) had mild pain (Table 3); 5 of them had an VNS=0 (meaning 41.67% of patients had no pain at all). Patients perceived mean pain on the VNS of 1.58, which meant a mean reduction between initial and postoperative pain of 6.42 points (Table 2).

Over the following 24h, 2 patients went from mild to moderate pain. Thus, 4 patients (33%) had moderate pain and 8 patients (67%) continued with mild pain (Table 3). Although there were no patients with no pain at all, the mean pain experienced was 2.92 points on the VNS, with a mean reduction of 5.08 points between pre-block pain and pain 24h after surgery (Table 2).

In the immediate postoperative period, two patients had a VNS greater than 3, and therefore rescue analgesic therapy with intravenous metamizole 2g was prescribed. However, these patients’ pain persisted and 2mg of bolus intravenous morphine chloride was administered. At 24h after surgery, two other patients had an VNS greater than 3, which was treated with 2g of intravenous metamizole.

In all patients, the PENG block provided analgesia, as it decreased the VNS for pain by at least 3 points at all time points assessed (Fig. 3; Table 2). This facilitated both patient transfer and positioning for dural puncture and spinal anaesthesia, and for the lateral decubitus procedure, all without haemodynamic alteration or exacerbation of pain.

In all cases the patient was able to get up 24h after surgery, start ambulation at 48h, and be discharged home in the first week after surgery.

The mean VNS score ranged from 8 before the PENG block to .5 after surgery. It subsequently increased to 1.58 points in the immediate postoperative period and 2.92 points 24h after surgery, without reaching baseline pain values in any case. In some cases, pain decreased completely, up to 10 points. The difference in pain scores was statistically significant (p<.001) (Table 2).

Motor block recovery was complete within 90±36min following the intervention. No complications attributable to the block were recorded. Patient satisfaction was high in all cases except for one patient, who rated it as low. The physician and nurse responsible for pain assessment and management rated satisfaction as high in all cases.

DiscussionHip fracture analgesia, despite its increasing incidence, remains a challenge for the orthopaedic surgical team. Traditional analgesic blocks are partial and provide inconsistent analgesia, as they do not affect all of the sensory nerves innervating the joint and cause prolonged motor blockade.6

The PENG block was first described by Girón-Arango et al.2 for postoperative analgesia in orthopaedic hip surgery. It blocks the branches of the femoral nerve, obturator nerve, and obturator accessory nerve, which innervate the anterior hip capsule, the area with the greatest sensory innervation, making it ideal as an analgesic procedure in hip fractures.2,3,6 Its application in the preoperative period provides significant advantages: patient transfer, ideal position for dural puncture and spinal anaesthesia, and positioning of the patient in lateral decubitus for surgery, without exacerbation of pain.

It cannot be used as an isolated anaesthetic procedure, as it does not act on the posterior area of the joint, which is innervated by the sacral plexus or the branches of the lumbar plexus superior to the area of the block. Thus, the lateral femoral cutaneous and iliohypogastric nerves, responsible for the sensory innervation of the lateral cutaneous region of the thigh, the area of the incisions for hip arthroplasty, would not be blocked.3

In this study, no motor deficit or clinically evident weakness was generated, allowing early mobilisation of patients without pain both preoperatively and early postoperatively, facilitating their rehabilitation. There was also no sympathetic blockade or haemodynamic alteration, as this technique only blocks the sensitive joint branches unilaterally.5,6 However, a review of the literature shows cases where quadriceps weakness occurred, probably because the anaesthetic was incorrectly administered around the femoral nerve, and this was blocked. These are usually mild motor blocks when local anaesthetics are used at low concentrations.7

The use of colour Doppler allowed verification of the location of the femoral artery and vein and avoided accidental intravascular punctures. Unintentional puncture of the urinary bladder due to an injection medial to the ileopectineal eminence, given the direction of the needle and the adjacent anatomical structures, is another possible complication resulting from a poorly performed technique, although this was not recorded in our study.

One of the drawbacks of this regional technique is the limited duration of analgesia, depending on the type and dose of local anaesthetic used, which could be solved with the placement of catheters to administer perfused local anaesthetics.8 This was not used in the cases included in the study, to avoid sources of infection in oncology patients.

In addition to this continuous block, other novel indications have been described: prevention of undesirable adductor muscle spasm by obturator nerve stimulation during transurethral resection of lateral bladder tumours9; anaesthetic technique for ligation of varicose veins and phleboextractions10; analgesic adjunct for hip pain due to vaso-occlusive crises in sickle cell disease.11

This case series has certain limitations. The design is not comparative with other traditionally used regional techniques. Several studies already point to a more satisfactory analgesia of the PENG block for hip fractures and arthroplasty compared to other blocks, such as the 3-in-1 block, the femoral nerve block and the iliac fascia block, as the latter do not reach the obturator nerve.3,12–14 Other limitations of this study are the small sample size, the fact that the patients came from a single hospital centre and the large proportion of participants on chronic analgesic treatment for tumour pathology. Randomised controlled trials with larger sample sizes are required to corroborate the effectiveness of PENG block as an analgesic/anaesthetic technique for hip fractures, as well as its comparison with other traditionally used regional techniques.

ConclusionThe PENG (PEricapsular Nerve Group) block is an effective regional analgesic technique.

It appears to solve the problem of incomplete analgesic coverage encountered with most previously described nerve block techniques for hip arthroplasty and fractures.

It reduces the use of systemic analgesics and their associated undesirable effects. Together with the low motor compromise it generates, it favours early mobility and rehabilitation, and a reduction in falls due to limb weakness, thus reducing hospital stay and costs.

Despite the promise of this blockade, well-designed randomised clinical trials are needed.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence III.

FundingThis research study has not received specific support from public sector agencies, the commercial sector, or non-profit organisations.

AuthorshipAzucena Martínez Martín assisted in the design and conduct of the study, data and image acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, drafting of the manuscript and critical revision. She approved its final version and agrees with its publication.

María Pérez Herrero conceived the idea, assisted in the design, and conduct of the study, acquisition of data and images, analysis, and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision. She approved its final version and agrees with its publication.

Belén Sánchez Quirós assisted in the drafting of the manuscript and critical revision. She approved its final version and agrees with its publication.

Rocío López Herrero assisted in the drafting of the manuscript and in the critical revision. She approved its final version and agrees with its publication.

Patricia Ruiz Bueno assisted in the drafting of the manuscript and in the critical revision. She approved its final version and agrees with its publication.

Sara Cocho Crespo assisted in the drafting of the manuscript and in the critical revision. She approved its final version and agrees with its publication.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethics Committee approvalProject approved by CEIC of the HCUV dated.