Diagnosing prosthetic joint infection (PJI) remains challenging, as no single test can definitively confirm or rule out infection. Current diagnostic criteria rely on a combination of clinical, laboratory, and microbiological data. Lipocalin-2 (LCN2) has emerged as a potential biomarker for PJI, particularly in acute cases. However, its diagnostic role in chronic PJI and aseptic failures is not well established. This study aimed to evaluate the diagnostic performance of synovial LCN2 in chronic PJI.

Material and methodsWe conducted a prospective study of patients undergoing revision total hip or knee arthroplasty between April 2022 and April 2023. Cases were initially classified preoperatively as aseptic or septic according to the European Bone and Joint Infection Society (EBJIS) criteria, based on the tests available before surgery. After surgery, the EBJIS criteria were reapplied to establish the final diagnosis. Synovial LCN2 levels were compared between groups, and diagnostic performance was assessed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis.

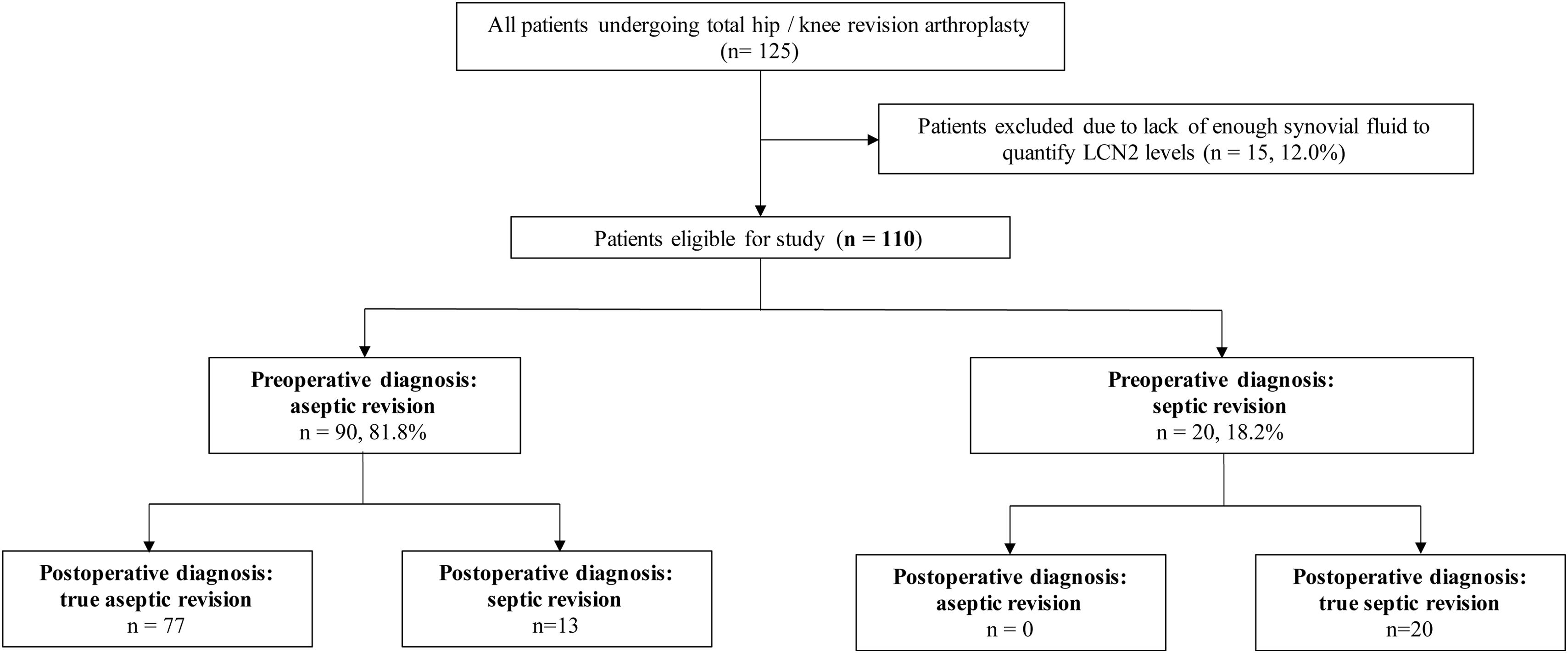

ResultsOf 125 patients undergoing revision surgery, 110 were included in the final analysis after excluding those with insufficient synovial fluid for LCN2 quantification. The median age was 75.0 years (IQR 68.0–81.0), and 65 patients (59.1%) were female. Based on preoperative evaluation, 90 cases (81.8%) were classified as aseptic failures and 20 (18.2%) as chronic PJI. However, according to the EBJIS criteria, 77 cases (70.0%) were ultimately diagnosed as aseptic and 33 (30.0%) as PJI. An LCN2 threshold of 266ng/mL was identified as the optimal cut-off for diagnosing PJI, showing a significant association with both the preoperative diagnosis of infection (p=0.012) and the definitive postoperative diagnosis (p=0.001). Elevated LCN2 levels were also significantly associated with increased serum C-reactive protein (CRP) levels (p=0.02). There were 13 cases with discordant diagnoses: initially considered aseptic but ultimately confirmed as septic. Among these, 9 cases (69.2%) exhibited elevated LCN2 levels.

ConclusionSynovial fluid LCN2 is a promising biomarker for the diagnosis of chronic PJI, especially in cases initially misclassified as aseptic. Its strong association with the final diagnosis of infection highlights its potential to enhance diagnostic accuracy. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings and support the incorporation of LCN2 into routine clinical practice.

El diagnóstico de la infección protésica articular (IPA) sigue representando un reto, ya que no existe una única prueba capaz de confirmar o descartar la infección de forma concluyente. Los criterios diagnósticos actuales se basan en la combinación de hallazgos clínicos, analíticos y microbiológicos. La lipocalina-2 (LCN2) ha emergido como un biomarcador potencial para la IPA, especialmente en los casos agudos. Sin embargo, su utilidad diagnóstica en la IPA crónica y en los fracasos asépticos no está bien establecida. El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar el rendimiento diagnóstico de la LCN2 sinovial en la IPA crónica.

Material y métodosSe llevó a cabo un estudio prospectivo en pacientes sometidos a artroplastia de revisión de cadera o rodilla entre abril de 2022 y abril de 2023. Los casos se clasificaron inicialmente de forma preoperatoria como sépticos o asépticos según los criterios de la European Bone and Joint Infection Society (EBJIS), en función de las pruebas disponibles antes de la cirugía. Tras la intervención, los criterios de la EBJIS se reaplicaron para establecer el diagnóstico definitivo. Se compararon los niveles de LCN2 entre grupos y se evaluó su rendimiento diagnóstico mediante curvas ROC.

ResultadosDe los 125 pacientes intervenidos, 110 fueron incluidos en el análisis final tras excluir aquellos sin suficiente cantidad de líquido sinovial para la cuantificación de LCN2. La mediana de edad fue de 75,0años (RIC: 68,0-81,0), y 65 pacientes (59,1%) eran mujeres. Según la evaluación preoperatoria, 90 casos (81,8%) fueron clasificados como fracasos asépticos y 20 (18,2%), como IPA crónica. No obstante, tras aplicar los criterios EBJIS, 77 casos (70,0%) fueron diagnosticados finalmente como fracasos asépticos y 33 (30,0%) como IPA. Se identificó un umbral de 266ng/ml como valor óptimo de corte para el diagnóstico de IPA, mostrando una asociación significativa tanto con el diagnóstico preoperatorio de infección (p=0,012) como, con mayor fuerza, con el diagnóstico postoperatorio definitivo (p=0,001). Los niveles elevados de LCN2 también se asociaron significativamente con niveles elevados de proteína C reactiva (PCR) en suero (p=0,02). En total, hubo 13 casos con diagnóstico discordante: clasificados inicialmente como asépticos pero confirmados postoperatoriamente como infecciosos. De ellos, 9 casos (69,2%) presentaban niveles elevados de LCN2.

ConclusiónLa LCN2 en líquido sinovial se perfila como un biomarcador prometedor para el diagnóstico de la IPA crónica, especialmente en aquellos casos inicialmente mal clasificados como fracasos asépticos. Su fuerte asociación con el diagnóstico definitivo de infección respalda su posible utilidad para mejorar la precisión diagnóstica. Se requieren estudios prospectivos adicionales para validar estos hallazgos y respaldar su inclusión en la práctica clínica habitual.

Prosthetic joint infection (PJI) remains one of the most severe and challenging complications following total joint arthroplasty (TJA). It has been reported that up to 24% of revision procedures performed within the first five years after implantation may be due to previously unrecognised low-grade infections.1 Moreover, partial prosthetic revisions with intraoperative positive cultures have been associated with significantly worse five-year outcomes.2,3

Given these findings, accurate and timely diagnosis of PJI is essential, yet remains difficult to achieve, as no single test can definitively confirm or exclude infection. Current diagnostic guidelines are based on composite criteria that incorporate clinical presentation, inflammatory markers, synovial fluid analysis, microbiological culture, and histopathological findings.4,5 Despite these advances, misdiagnosis remains common, particularly in patients undergoing revision surgery for presumed aseptic failure.6

In recent years, the search for novel biomarkers in serum and synovial fluid has gained interest as a means to improve diagnostic accuracy and facilitate the development of rapid, point-of-care testing tools. Promising candidates such as α-defensin, D-dimer, and calprotectin have shown encouraging results in the diagnosis of PJI.7–10

Lipocalin-2 (LCN2) is an acute-phase protein involved in the innate immune response, predominantly secreted by neutrophils, hepatocytes, and renal tubular cells. It contributes to host defence by sequestering iron-loaded siderophores, thus limiting bacterial growth. Under normal conditions, LCN2 circulates at low concentrations (approximately 20ng/mL), but its levels rise markedly in response to infection, inflammation, and tissue injury. LCN2 has recently been proposed as a potential biomarker for PJI. Previous research from our group demonstrated significantly elevated LCN2 levels in acute PJI, supporting its potential role in infection diagnosis.11 However, its usefulness in distinguishing chronic infections from true aseptic failures remains uncertain.

This study aims to evaluate the diagnostic performance of synovial LCN2 in patients undergoing revision hip or knee arthroplasty, with particular emphasis on cases initially classified as aseptic that were subsequently reclassified as infected. If validated, LCN2 could represent a valuable biomarker for detecting occult infections and improving diagnostic accuracy in revision surgery. The specific objective was to analyse the correlation between synovial LCN2 levels and both the preoperative clinical suspicion and the definitive postoperative diagnosis of PJI, as well as to explore its association with established diagnostic parameters.

Material and methodsStudy design and patient selectionThis single-centre prospective study included consecutive patients undergoing hip or knee revision arthroplasty at our institution between April 2022 and April 2023. Eligible participants were those with a preoperative diagnosis of aseptic loosening or chronic PJI (Fig. 1). Exclusion criteria included patients undergoing revision due to periprosthetic fracture or dislocation, as well as those undergoing the second stage of a two-stage revision for infection.

Preoperative evaluationAll patients underwent a thorough physical examination and plain radiographic evaluation. The routine preoperative laboratory workup included C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and D-dimer levels. In cases with suspected infection, synovial fluid aspiration was performed – CT-guided in hip cases – for microbiological culture and, when feasible, white blood cell count. White blood cell (WBC) scintigraphy was performed in equivocal at the clinican's discretion. The following variables were recorded: demographic characteristics, time from primary arthroplasty to revision, indication for revision, affected joint (hip or knee), microbiological findings, synovial fluid analysis, histopathology, and baseline serum biomarkers (CRP, ESR, and D-dimer). Cases were initially classified preoperatively as aseptic or septic according to the European Bone and Joint Infection Society (EBJIS) criteria, based on the tests available before surgery.4

Surgical protocol and sample collectionAll procedures were carried out in a laminar airflow operating room by orthopaedic surgeons specialised in revision arthroplasty. Standard antibiotic prophylaxis was administered preoperatively. Intraoperatively, synovial fluid was collected for white blood cell count, neutrophil percentage, and microbiological analysis. The microbiological protocol included two synovial fluid samples (routinely inoculated into blood culture bottles), two tissue samples from the neo-synovium for culture, and two additional samples for histopathological evaluation. In addition, for research purposes, at least 1mL of synovial fluid was collected and immediately stored at −80°C. After surgery, the EBJIS criteria were reapplied to establish the final diagnosis of PJI.4

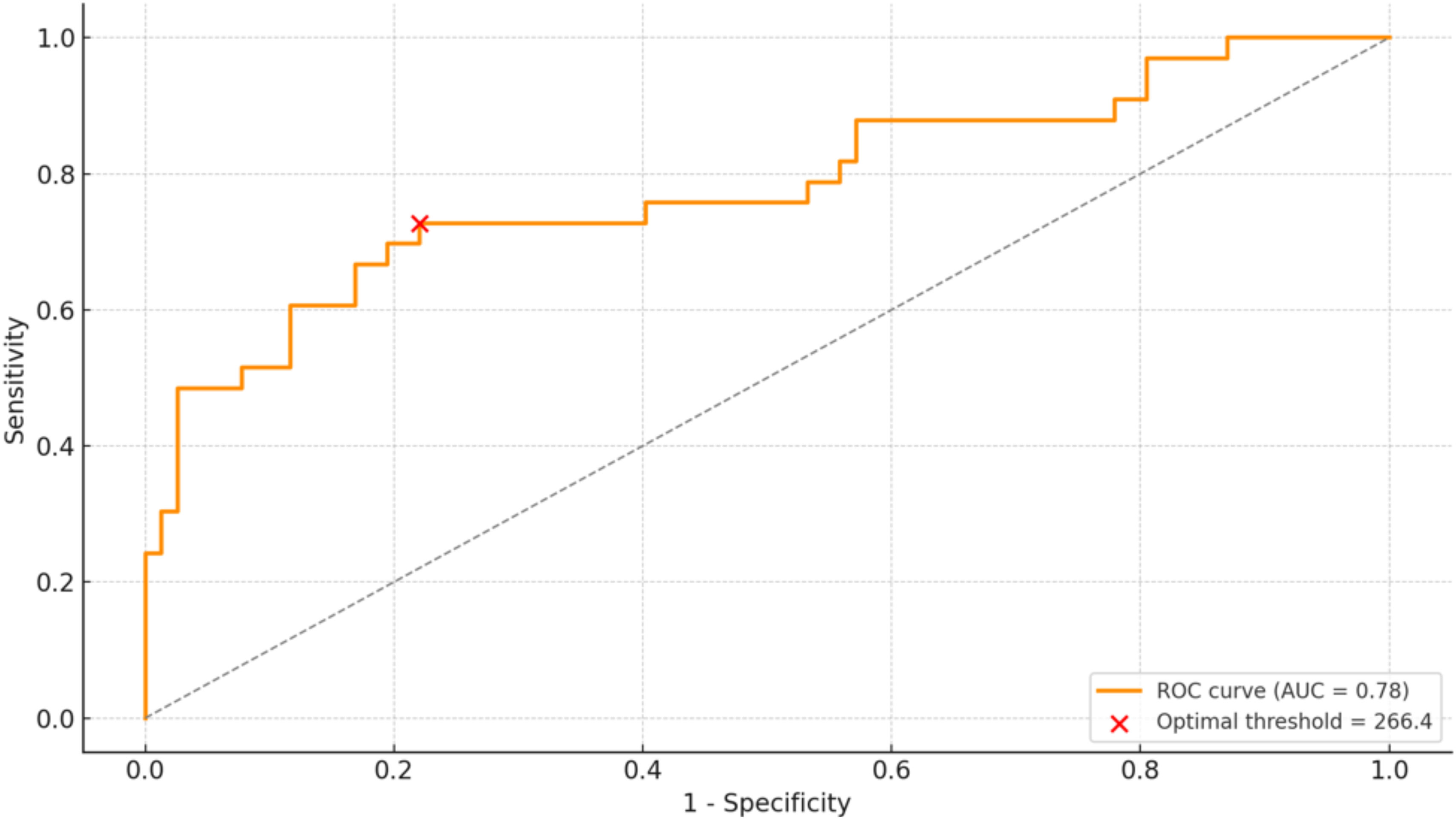

Lipocalin-2 quantificationLCN2 levels were measured in synovial fluid using a modified enzyme immunoassay with chemiluminescence (Architect Urine NGAL, Abbott Laboratories) on the ARCHITECT i1000SR platform (Abbott Laboratories, Madrid, Spain), following manufacturer instructions. The assay utilizes paramagnetic particles conjugated with an anti-NGAL antibody and a secondary antibody labeled with acridinium. Samples were diluted 1:10 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). If concentrations exceeded the detection limit (1500ng/mL), an additional 1:10 dilution was performed. The primary endpoint was to differentiate PJI from aseptic failure. The diagnostic performance of LCN2 was evaluated using the area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The optimal cut-off value maximizing sensitivity and specificity was determined.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables were reported as mean±standard deviation (SD) or median [interquartile range (IQR)], depending on normality (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). They were compared using Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. Biomarkers were dichotomized based on predefined thresholds: CRP >1mg/dL, ESR >30mm/h, and D-dimer >850ng/mL. Revisions were classified as “early” if performed within the first 24 months following the index arthroplasty. Categorical variables were presented as absolute frequencies (%) and analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. The predictive value of LCN2 was evaluated through ROC curve analysis, determining the cut-off point that provided the optimal sensitivity/specificity balance, as well as thresholds for 90% sensitivity and specificity. Additionally, an internal validation of the LCN2 cut-off by non-parametric bootstrapping (1000 resamples) was performed. In each resample, the optimal threshold was recalculated using Youden's index. We also reported bootstrap distributions of sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV at the determined cut-off point. Patients were then dichotomized based on LCN2 levels, categorized as either below or equal to/exceeding the identified threshold. Finally, we assessed whether combining LCN2 with CRP enhanced diagnostic performance by comparing AUCs from logistic regression models. A two-tailed p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using Jamovi v2.0.0.0. The ROC curve analysis and the scatterplot were conducted using OpenAI's data visualization tools.

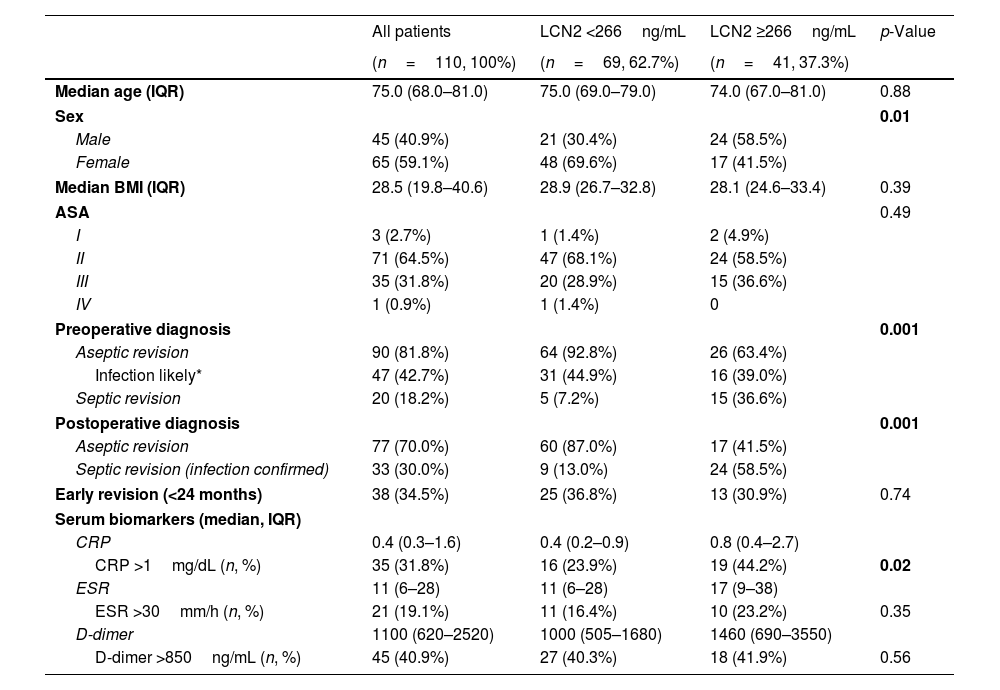

ResultsDuring the study period, 125 patients underwent hip or knee revision arthroplasty. Of these, 15 cases (12%) were excluded due to insufficient synovial fluid volume for LCN2 quantification. The final analysis included 110 patients (Table 1). The median age was 75.0 years (IQR 68.0–81.0), and 65 patients (59.1%) were female. A total of 22 cases (20.0%) had at least one positive microbiological culture. The median time from index arthroplasty to revision was 44 months (IQR 13.1–105.0).

Baseline demographics of patients included in the final analysis, categorized by synovial fluid Lipocalin-2 (LCN2) levels.

| All patients | LCN2 <266ng/mL | LCN2 ≥266ng/mL | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=110, 100%) | (n=69, 62.7%) | (n=41, 37.3%) | ||

| Median age (IQR) | 75.0 (68.0–81.0) | 75.0 (69.0–79.0) | 74.0 (67.0–81.0) | 0.88 |

| Sex | 0.01 | |||

| Male | 45 (40.9%) | 21 (30.4%) | 24 (58.5%) | |

| Female | 65 (59.1%) | 48 (69.6%) | 17 (41.5%) | |

| Median BMI (IQR) | 28.5 (19.8–40.6) | 28.9 (26.7–32.8) | 28.1 (24.6–33.4) | 0.39 |

| ASA | 0.49 | |||

| I | 3 (2.7%) | 1 (1.4%) | 2 (4.9%) | |

| II | 71 (64.5%) | 47 (68.1%) | 24 (58.5%) | |

| III | 35 (31.8%) | 20 (28.9%) | 15 (36.6%) | |

| IV | 1 (0.9%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0 | |

| Preoperative diagnosis | 0.001 | |||

| Aseptic revision | 90 (81.8%) | 64 (92.8%) | 26 (63.4%) | |

| Infection likely* | 47 (42.7%) | 31 (44.9%) | 16 (39.0%) | |

| Septic revision | 20 (18.2%) | 5 (7.2%) | 15 (36.6%) | |

| Postoperative diagnosis | 0.001 | |||

| Aseptic revision | 77 (70.0%) | 60 (87.0%) | 17 (41.5%) | |

| Septic revision (infection confirmed) | 33 (30.0%) | 9 (13.0%) | 24 (58.5%) | |

| Early revision (<24 months) | 38 (34.5%) | 25 (36.8%) | 13 (30.9%) | 0.74 |

| Serum biomarkers (median, IQR) | ||||

| CRP | 0.4 (0.3–1.6) | 0.4 (0.2–0.9) | 0.8 (0.4–2.7) | |

| CRP >1mg/dL (n, %) | 35 (31.8%) | 16 (23.9%) | 19 (44.2%) | 0.02 |

| ESR | 11 (6–28) | 11 (6–28) | 17 (9–38) | |

| ESR >30mm/h (n, %) | 21 (19.1%) | 11 (16.4%) | 10 (23.2%) | 0.35 |

| D-dimer | 1100 (620–2520) | 1000 (505–1680) | 1460 (690–3550) | |

| D-dimer >850ng/mL (n, %) | 45 (40.9%) | 27 (40.3%) | 18 (41.9%) | 0.56 |

IQR: interquartile range; BMI: body mass index; CRP: C-reactive protein; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Based on the available preoperative tests, 90 cases (81.8%) were classified as aseptic failures and 20 cases (18.2%) as chronic infections. After surgery, the EBJIS criteria were reapplied, resulting in 77 cases (70.0%) being classified as aseptic and 33 cases (30.0%) as PJI.

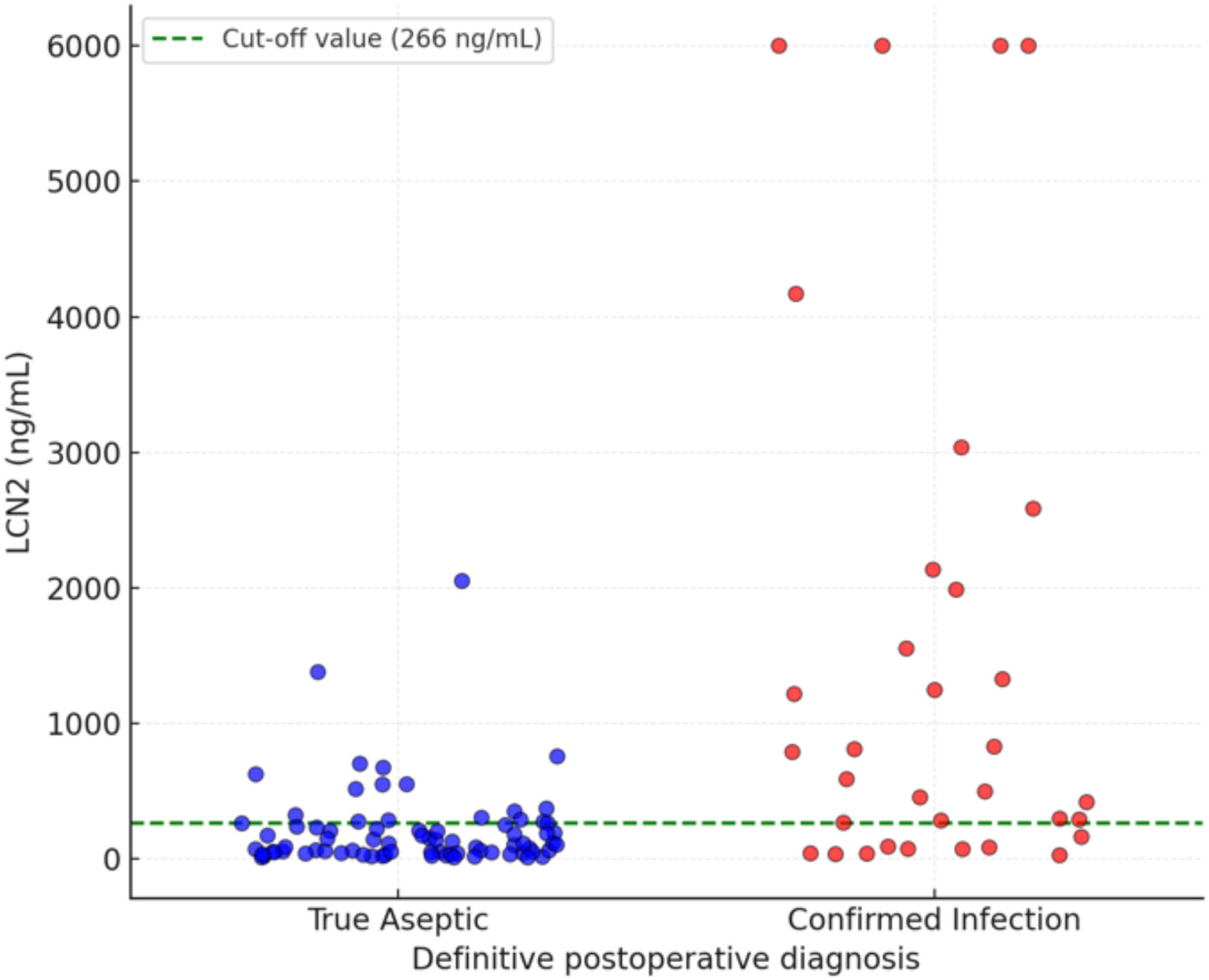

A synovial fluid LCN2 concentration of ≥266ng/mL (Youden's J=0.506; AUC=0.780) was identified as the optimal cut-off value for distinguishing PJI, providing the best balance between sensitivity and specificity (Fig. 2). The bootstrap median threshold was 289.7ng/mL with a 95% percentile interval of 266.4–808.8ng/mL; 61.9% of optimal thresholds fell within ±25ng/mL of 266. At this threshold, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were 73%, 78%, 59%, and 87%, respectively. Elevated LCN2 levels (≥266ng/mL) were observed in 41 cases (37.3%) and were significantly associated with the preoperative diagnosis of chronic infection (p=0.012), with an even stronger correlation with the definitive postoperative diagnosis (p=0.001) (Fig. 3). Among the 90 cases that underwent revision surgery without an initial diagnosis of infection, 47 fulfilled certain criteria and were therefore classified as “infection likely” according to the EBJIS definition. Within this subgroup, 16 patients presented elevated LCN2 levels (≥266ng/mL).

Elevated LCN2 levels also showed a significant association with increased serum CRP concentrations (p=0.02). Using logistic models, adding CRP to LCN2 increased the AUC from 0.780 to 0.804. With decision rules, “LCN2≥266 OR CRP>1” achieved sensitivity 84.4% and NPV 90.0%, whereas “LCN2≥266 AND CRP>1” yielded specificity 93.4% and PPV 70.6%. Finally, early revision cases did not show a significant association with LCN2 elevation or with any of the serum biomarkers evaluated.

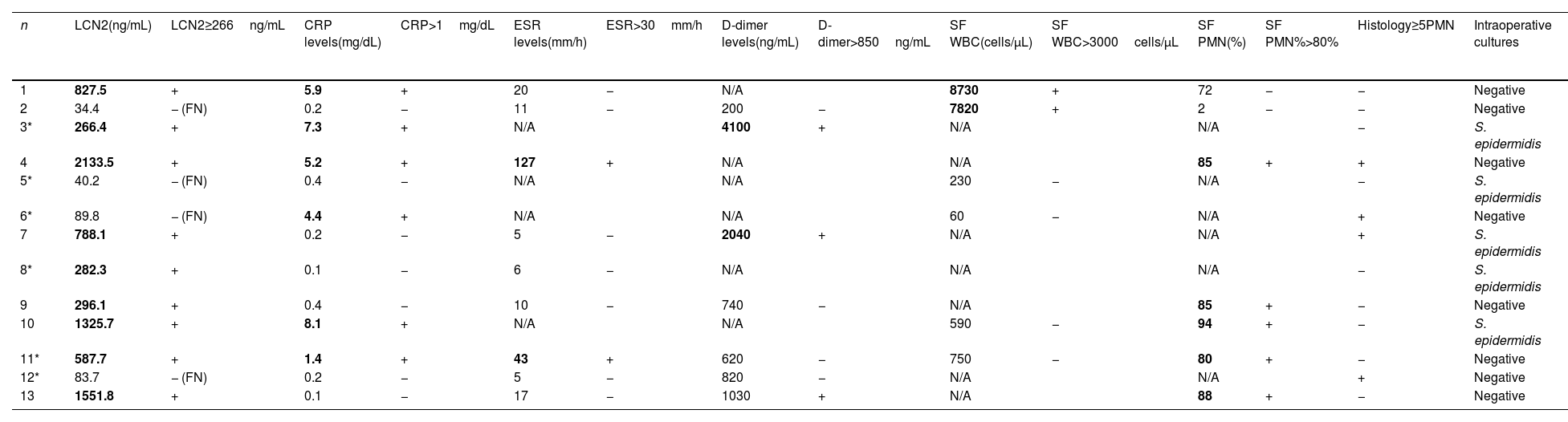

Overall, there were 13 cases with discordant diagnoses, which were initially classified as aseptic but ultimately diagnosed as PJI (Table 2). Among these, 6 were assigned to the “infection likely” category, of which 3 had elevated LCN2 levels (≥266ng/mL). Out of the 13 cases with discordant diagnoses, 9 cases (69.2%) had elevated LCN2 levels, while 4 cases presented with lower concentrations, resulting in false-negative findings. Aside, CRP >1mg/dL was found in 6 cases, synovial PMN% ≥80% in 5 cases and synovial WBC >3000cells/μL in 2 cases. Intraoperative cultures were positive in 7 cases.

Serum biomarkers levels, synovial fluid cell count, histology and cultures from the 13 patients showing a discrepancy between the preoperative and definitive postoperative diagnosis according to the EBJIS criteria, where the revision was initially considered aseptic (cases marked with * fulfilled the “infection likely” criteria) but ultimately classified as “confirmed infection”.

| n | LCN2(ng/mL) | LCN2≥266ng/mL | CRP levels(mg/dL) | CRP>1mg/dL | ESR levels(mm/h) | ESR>30mm/h | D-dimer levels(ng/mL) | D-dimer>850ng/mL | SF WBC(cells/μL) | SF WBC>3000cells/μL | SF PMN(%) | SF PMN%>80% | Histology≥5PMN | Intraoperative cultures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 827.5 | + | 5.9 | + | 20 | − | N/A | 8730 | + | 72 | − | − | Negative | |

| 2 | 34.4 | − (FN) | 0.2 | − | 11 | − | 200 | − | 7820 | + | 2 | − | − | Negative |

| 3* | 266.4 | + | 7.3 | + | N/A | 4100 | + | N/A | N/A | − | S. epidermidis | |||

| 4 | 2133.5 | + | 5.2 | + | 127 | + | N/A | N/A | 85 | + | + | Negative | ||

| 5* | 40.2 | − (FN) | 0.4 | − | N/A | N/A | 230 | − | N/A | − | S. epidermidis | |||

| 6* | 89.8 | − (FN) | 4.4 | + | N/A | N/A | 60 | − | N/A | + | Negative | |||

| 7 | 788.1 | + | 0.2 | − | 5 | − | 2040 | + | N/A | N/A | + | S. epidermidis | ||

| 8* | 282.3 | + | 0.1 | − | 6 | − | N/A | N/A | N/A | − | S. epidermidis | |||

| 9 | 296.1 | + | 0.4 | − | 10 | − | 740 | − | N/A | 85 | + | − | Negative | |

| 10 | 1325.7 | + | 8.1 | + | N/A | N/A | 590 | − | 94 | + | − | S. epidermidis | ||

| 11* | 587.7 | + | 1.4 | + | 43 | + | 620 | − | 750 | − | 80 | + | − | Negative |

| 12* | 83.7 | − (FN) | 0.2 | − | 5 | − | 820 | − | N/A | N/A | + | Negative | ||

| 13 | 1551.8 | + | 0.1 | − | 17 | − | 1030 | + | N/A | 88 | + | − | Negative |

SF: synovial fluid; LCN2: Lipocalin-2; CRP: C-reactive protein; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; WBC: white blood cell count; PMN: polymorphonuclear cells; FN: false negative; N/A: not available. Values qualifying as positive for infection are bold highlighted.

LCN2 has demonstrated utility as a biomarker in various fields, including acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery12 and breast cancer prognosis.13 While its role in distinguishing septic from aseptic joint failure has been previously explored,14 its clinical value remains to be clearly defined.

This study aimed to validate the diagnostic performance of synovial LCN2 in differentiating chronic PJI from aseptic failure, particularly in cases with inconclusive standard criteria. Our results show significantly higher LCN2 levels in chronic PJI, supporting its value as a diagnostic biomarker. The strong correlation with positive intraoperative cultures further suggests that LCN2 may help predict microbiological positivity, which is especially relevant in culture-negative infections.15 Combining LCN2 with CRP increased overall discrimination and offered complementary operating characteristics: an “OR” strategy (LCN2 or CRP positive) supports preoperative screening and rule-out decisions by prioritising sensitivity/NPV, whereas an “AND” strategy supports rule-in decisions by prioritising specificity/PPV and minimising false positives. These simple combinations are clinically practical and can be tailored to the diagnostic intent.

In the present series, a total of thirteen cases were misclassified preoperatively as aseptic but were ultimately diagnosed as infections. Among these, 9 (69.2%) had elevated LCN2 levels, which could have served as an early diagnostic clue. Interestingly, 6 of the discordant cases belonged to the “infection likely” category according to the EBJIS criteria, and half of them already showed elevated LCN2 concentrations. All these findings suggest that LCN2 may be particularly valuable in clinically equivocal situations, such as the “infection likely” group, by supporting earlier recognition of otherwise occult infections and guiding surgical decision-making. However, the observed PPV (59%) should be interpreted in the context of our cohort's PJI prevalence and the possibility that LCN2 rises in non-prosthetic inflammatory conditions (e.g., systemic inflammation or other non-PJI infections), leading to false positives. Accordingly, a positive LCN2 result should not be used in isolation to rule in PJI; it should prompt confirmatory testing or be incorporated into a composite approach with CRP (AND strategy) when high specificity is required. By contrast, the high NPV supports its use as a rule-out tool.

A key advantage of LCN2 is its rapid quantification, since results are available in approximately 30min, making it a potential intraoperative decision-making tool, particularly in cases of diagnostic uncertainty. Zhang et al. recently evaluated a rapid test for LCN2 with excellent diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity 93.3%, specificity 92.9%) using a cut-off of 369ng/mL.16 This supports the feasibility of LCN2-based rapid diagnostics, though further validation is needed.

An ongoing challenge is defining a standardised diagnostic threshold. We identified 266ng/mL as the optimal cut-off, though factors such as infection chronicity and joint type may influence this value. For example, Vergara et al. reported a lower cut-off (152ng/mL) when including acute infections.11 Future studies should assess whether different thresholds are needed based on infection type or joint location. Although our findings support the role of LCN2 in chronic PJI, further prospective, multicentre studies are required to confirm its generalisability. Incorporating LCN2 into existing diagnostic algorithms could enhance accuracy and improve perioperative decision-making.

There is an ongoing search for the perfect biomarker to dichotomize PJI vs aseptic failure, but none is yet definitive. Both serum CRP and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) remain first-line screens with variable accuracy (CRP sensitivity 74–94%, specificity 66–92%; ESR 75–91% and 72–91%), and CRP is included in most standardized criteria.17 Serum D-dimer shows moderate, heterogeneous performance (sensitivity 74–82%, specificity 70–79%) and is influenced by sample type and comorbidities; nevertheless, several series suggest normal values are uncommon in chronic PJI and its NPV can serve as a rule-out test.18 Among synovial assays, α-defensin (a neutrophil-derived antimicrobial peptide) performs best with laboratory ELISA (reports up to 96% sensitivity and 97% specificity) and is scored as a minor criterion in contemporary definitions; however, reduced performance and occasional false positives are described with metallosis or crystal disease. Lateral-flow α-defensin has lower sensitivity (limiting rule-out) but retains high specificity, supporting perioperative rule-in.19,20 Synovial calprotectin (a neutrophil-derivated antimicrobial complex) also shows high accuracy (pooled sensitivity 92–96%, specificity 92–97%) and is practical as a rapid rule-out test.21 Leukocyte esterase likewise achieves high pooled accuracy (sensitivity/specificity around 87–96%), is inexpensive and accessible, but its colorimetric readout is operator-dependent and can be impaired by blood contamination of synovial fluid.22 In our cohort, synovial LCN2 at 266ng/mL achieved an AUC of 0.78 with 73% sensitivity and 78% specificity, which is comparable to common serum markers yet below the top synovial assays, while adding signal in “infection likely” cases; combining LCN2 with CRP (AND strategy) may enhance rule-in specificity.

This study has several limitations that should be highlighted. First, the diagnostic definition used may be considered a limitation: we adopted EBJIS as the reference standard because it aims to minimise missed infections and offers a three-scenario framework that is particularly useful preoperatively, albeit at the potential cost of some overdiagnosis23; comparative studies and a multicentre validation support these advantages and indicate higher sensitivity without evident loss of specificity.24 Second, a relatively high proportion of dry taps (n=30, 27.3%), predominantly in hip revisions, limited the availability of synovial biomarkers and thus the completeness of EBJIS classification. Dry taps have been consistently reported in the literature and represent a practical challenge when applying diagnostic definitions based on synovial fluid analysis.25,26 Third, the precision of the optimal LCN2 cut-off is constrained by sample size and case mix; internal bootstrap validation showed variability with a right-skewed distribution, so we report performance at a prespecified threshold of 266ng/mL and acknowledge the need for external validation in larger cohorts. Finally, comorbidities that may elevate LCN2 were not collected systematically, precluding adjustment for potential confounding and limiting the interpretability of positive results.

In conclusion, synovial fluid LCN2 appears to be a useful biomarker for identifying chronic PJI, particularly in patients initially misclassified as aseptic. Its strong association with infection and culture results suggests that it could enhance diagnostic precision, pending further validation in larger cohorts.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence II.

ORCID IDJenaro A. Fernández-Valencia: 0000-0002-6381-9502

Marta Sabater-Martos: 0000-0002-9350-3648

Eduard Tornero: 0000-0002-9404-3719

Andrea Vergara: 0000-0002-5046-4490

Andrés Combalia: 0000-0002-1035-9469

Laura Morata: 0000-0001-5795-0814

Alex Soriano: 0000-0002-9374-0811

Ethical considerationsThe authors confirm that the current study was reviewed by an Ethics Committee for Clinical Investigation, approved under the code HCB/2023-0493 and was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration.

FundingThis study was conducted with the support of a grant from the Spanish Society of Orthopedic Surgery and Traumatology (SECOT).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.