Complications from cast removal are infrequent but can cause permanent skin sequelae. Formal training in cast removal is limited during residency. This study aimed to develop a plaster cast removal simulation model for resident training.

MethodsQuasiexperimental study. A pediatric forearm phantom with temperature sensors was designed to simulate forearm cast removal. Six first-year orthopedic residents with no prior cast removal experience and two experts were evaluated. The residents underwent an initial evaluation, followed by an instruction session, and a final evaluation. Performance was assessed using a specific ratings scale (SRS), the Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS) guideline, procedure time, and temperature measurement. Median scores with ranges were reported, and pre- and posttraining performances were compared using the Wilcoxon test. Experts scores were compared with resident scores using the Mann–Whitney test. The statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

ResultsSignificant improvements in OSATS [(pre 22 points (range: 20–24); posttraining 25 (range: 25–28) (p=0.03)] and SRS [pre 8.5 points (range: 7–9); post 10 points (range: 8–10) (p=0.02)] were observed. No differences were found in temperature (p=0.50) and procedure time (p=0.09). When comparing residents’ post-training scores with those of experts, no significant differences were found in OSATS (p=0.16), SRS (p=0.11), temperature measurement (p=0.50), or procedure time (p=0.09).

ConclusionsThe plaster cast removal simulation model proved to be an effective training tool for residents, enabling them to achieve expert-level competency. Significant improvements were observed in OSATS and SRS scores post-training, highlighting the positive impact of the intervention on this skill.

Las complicaciones del retiro de yeso son poco frecuentes, pero pueden causar secuelas cutáneas. La formación de esta habilidad es limitada durante la residencia. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo desarrollar un modelo de simulación para la extracción de yeso para el entrenamiento de residentes.

MétodosEstudio cuasi-experimental. Se diseñó un modelo de antebrazo pediátrico con sensores de temperatura para simular la extracción de yeso del antebrazo. Se evaluaron seis residentes de primer año de ortopedia sin experiencia previa en la extracción de yeso y dos expertos. Los residentes realizaron una evaluación inicial, seguida de una sesión de instrucción y una evaluación final. El rendimiento se evaluó mediante una escala específica de evaluación (EEE), la guía Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS), el tiempo del procedimiento y la medición de la temperatura. Se informaron medianas con rangos y se compararon los rendimientos pre y post-entrenamiento mediante la prueba de Wilcoxon. Las puntuaciones de los expertos se compararon con las de los residentes mediante la prueba de Mann-Whitney. La significación estadística se estableció en p<0,05.

ResultadosSe observaron mejoras significativas en las puntuaciones de OSATS (pre 22 puntos [rango: 20-24]; post-entrenamiento 25 [rango: 25-28], p=0,03) y EEE (pre 8,5 puntos [rango: 7-9]; post 10 puntos [rango: 8-10], p=0,02). No se encontraron diferencias en la temperatura (p=0,50) ni en el tiempo del procedimiento (p=0,09). Al comparar las puntuaciones post-entrenamiento de los residentes con las de los expertos, no se encontraron diferencias significativas en OSATS (p=0,16), en EEE (p=0,11), en medición de temperatura (p=0,50) ni en el tiempo del procedimiento (p=0,09).

ConclusionesEl modelo de simulación para la extracción de yeso demostró ser una herramienta de entrenamiento efectiva para los residentes, permitiéndoles alcanzar un nivel de competencia comparable al de los expertos. Se observaron mejoras significativas en las puntuaciones de OSATS y EEE tras el entrenamiento, lo que resalta el impacto positivo de la intervención en el desarrollo de esta habilidad.

The application and subsequent removal of casts are common procedures in pediatric orthopedics. However, this procedure is not free of complications, with burns and abrasions being the most common adverse events, occurring with a prevalence ranging from 0.1% to 0.72%.1,2 In addition to the direct harm caused to patients, these injuries result in substantial indirect costs, reported to be from 15,898 to 445,144 USD per patient per year.1,3

Thermal injury may occur when friction between the cast and the blade elevates above 50°C.4 On the other hand, abrasions occur when the pressure exerted on the cast does not allow the underlying skin to oscillate, thus the skin becomes immobile and susceptible to being cut by the blade.5 Although multiple factors contribute to the occurrence of burns and abrasions during cast removal, studies have revealed that they are significantly more frequent when the procedure is performed by residents or in the emergency department, with incidence rates being up to eight times higher.2 Surprisingly, despite the increased risk and frequency of complications, a survey of 10 training programs in the United States found that less than one hour of formal training is typically dedicated to this essential skill.6

Simulation training provides a valuable opportunity for trainees to practice and develop necessary skills in a safe and controlled environment, mitigating risks to patients.7 By incorporating simulation into cast removal training, residents can enhance their proficiency in this procedure and reduce the likelihood of complications. In terms of costs, Bae et al. have shown that a 2.5h simulation training for orthopedic surgical residents was effective in reducing cast-saw injuries and had a high theoretical return on investment.8 Other studies have focused on burns by temperature of the blade. For example, Brubacher et al. showed that clinical experience was a predictor of decreased heat generation during cast removal9 and Ruder et al. showed that after one educational session there is a significant reduction in temperature.10 On the other hand, Liles et al. had focused on abrasion, showing that there is difference in this aspect between novices and experts in saw indentation.11 They have not focused on both aspects of the burns, nor have they clarified the curriculum along with its evaluation criteria.

This study aimed to develop a simulation model for cast removal training for orthopedic surgery residents, with its evaluation criteria.

MethodsParticipantsFirst-year residents from orthopedic surgery were invited to participate in the course, as part of a boot camp in the first month of residency. They voluntarily enrolled and provided informed consent. Residents with prior experience in cast removal were excluded from the study and if someone did not complete the training during the first month of residency. Pediatric orthopedic surgeons with more than 5 years of experience in the field were selected as experts. The expert team was divided into different groups to ensure that all the facets of the model were covered. Face and content validity was evaluated by four experts, who focused on design and visual presentation, while two experts participated in a single training session where their performance was assessed. This ensures a detailed and accurate evaluation of the design and visual experience of the model, without the influence of technical knowledge related to its training.

EthicsThe study protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee (ID 200821001).

Simulation model and training sessionWe aimed to develop a simulated training session, in which first year residents of orthopedic surgery would acquire basic skills cast removal. For this purpose we designed a cast removal model which was first evaluated by experts, who also did a training session. Afterwards the model was tested in first year residents before and after a training instruction. All the sessions were recorded and evaluated by a senior author.

Design of the cast removal modelThe cast removal model consists of a pediatric forearm phantom, which was selected for its low cost and because it has been used in other studies.9–11 Prior to installing the cast, black tape was attached to the cutting area simulating skin, using it because it was easy to distinguish damage. In the same area, 8 temperature sensors were installed and connected to an electronic model for delivering results (Fig. 1). The forearm cast was then installed using tubular support, a layer of 10CM×2.7M softband with 50% overlap, and three layers with 50% overlap 10cm×3m plaster bandages (Fig. 2). The casts were allowed to dry for 3 days, as this is considered the drying time according to the study of Szostakowski et al.12

For the temperature sensor, a digital development electronic board programmable in C++ is used, along with a 5″ LCD (liquid-crystal display) and a set of 8 digital temperature sensors called DS18B20. We used C++ because it is a versatile and high-performance programming language that combines the efficiency of C with modern object-oriented features, making it ideal for developing a wide range of applications, including this model. Each sensor contains a unique hexadecimal number for identification. The temperature data collected by each sensor are redirected to the LCD display, which graphically represents a forearm image with 8 points arranged in a zigzag pattern along the splint. The displayed image shows the sensed temperature and real-time color variations according to the thermal reading (Fig. 3).

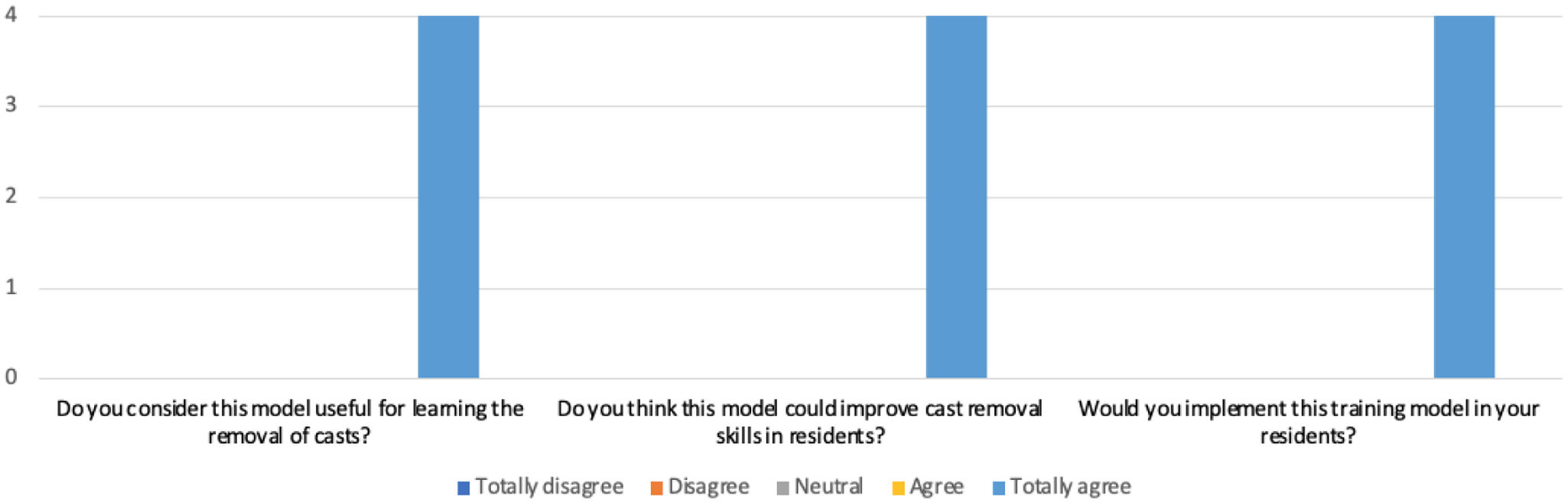

Appearance and content validityTo assess face and content validity, a Likert-type survey consisting of 8 questions was administered to 4 pediatric orthopedic surgeons who tested the model. The survey questions are provided in Table 1.

Experts evaluation of appearance and content validity of the model.

| Appearance validitya |

| How do you consider the size of the model? |

| How do you consider the thickness of the plaster in relation to a real one? |

| How do you consider the cutting sensation in relation to a real one? |

| How do you consider the thermal sensation in relation to a real one? |

| How do you consider the duration of the cut-off test? |

| Content validityb |

| Do you consider this model useful for learning the removal of casts? |

| Do you think this model could improve cast removal skills in residents? |

| Would you implement this training model in your residents? |

The residents underwent an initial recorded evaluation, they entered to a consult where one person of the investigation team was presented as the patient parent and asked about the procedure to the resident. No instruction about the saw technique was received.

Subsequently, they received training instruction from one of the experts, focusing on what is defined to be a “good technique”: use an “in then out” cast saw motion with frequent checking the blade temperature and cooling of the blade with a moist gauze.9,13 This was done with a 10min presentation, and a demonstration of the correct technique and main mistakes, afterwards the expert clarified any doubts. The session lasted 25min. Afterward, they underwent another recorded session that was analyzed, as the final evaluation. The experts performed one recorded cast removal procedure, which was used to compare with residents.

Training sessions were evaluated using the Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skill (OSATS) modified scale13 (Table 2), a specific rating scale (SRS) (Table 3), time taken to do the procedure and temperature measured with the sensor. The SRS was created by consensus of the authors. All videos were evaluated by one of the researchers who was blind to the student, but knew if it was a novice or expert and if it was the first or second session.

Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skill (OSATS) modified scale.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respect for tissue | Frequently used unnecessary force on tissue or caused damage by inappropriate use of instruments | – | Careful handling of tissue but occasionally caused inadvertent damage | – | Consistently handled tissue appropriately with minimal damage |

| Time and motion | Many unnecessary moves | – | Efficient time/motion, but some unnecessary moves | – | Economy of movement and maximum efficiency |

| Instrument handling | Repeatedly makes tentative or awkward moves with instruments | – | Competent use of instruments although occasionally appeared stiff and awkward | – | Fluid moves with instruments and no awkwardness |

| Flow of operation | Frequently stopped operating and seemed unsure of next move | – | Demonstrated some forward planning with reasonable progression of procedure | – | Obviously planned course of operation with effortless flow from one move to the next |

| Knowledge of specific procedure | Deficient knowledge needed specific instruction at most operative steps | – | Knew all important aspects of the operation | – | Demonstrated familiarity with all aspects of the operation |

OSATS score: each item was evaluated from 1 to 5 with a total score of 25 points.

Specific rating scale (SRS).

| Explains the procedure to the patient and accompanying persons |

| Obtains informed consent from parents/guardian in charge |

| Gathers necessary materials (oscillating saw, wet gauze, blunt scissors, pliers) |

| Puts on gloves |

| Demonstrates proper technique with the oscillating saw (utilizing good “up and down” motion) |

| Regularly implements cooling techniques (using wet gauze to cool the saw blade) |

| Uses pliers to open the plaster |

| Cuts bandage and padded cotton bandage with blunt scissors |

| Removes the plaster and disposes of it in the designated “garbage” container |

| Provides post-procedure instructions to patients and accompanying persons |

Total score of SRS: 10 points.

Since the variables were nonparametric and the small sample size, medians and their range were reported. Pre- and posttraining performance was compared using the Wilcoxon test, while expert versus resident scores were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney test. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ResultsAppearance and content validityFour experts evaluated the model by means of a survey on face and content. Regarding face validity, the best-rated item was shear sensation (median: 5 points, and the worst-rated item was thermal sensation (median: 4 points). Regarding content validity, all experts “strongly agreed” that the proposed model is a useful model and that they would implement it in their residents’ learning (Figs. 4 and 5).

Training evaluationSix first-year orthopedic residents, none of whom had previous experience in saw cast removal were evaluated. Two pediatric orthopedic surgeons with more than 5 years of experience were evaluated as experts.

Novices demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in OSATS scores from pre- to post-training [22 (IQR: 20–24); post 25 (IQR: 25–28) (p=0.03)] and in SRS [pre 8.5 (IQR: 7–9) and post: 10 (IQR: 8–10) (p=0.02)]. When comparing residents’ post training with experts, there were no significant differences in OSATS score (p=0.16), SRS (p=0.11), temperature (p=0.50) or time spent (p=0.09).

DiscussionSimulation has emerged as a valuable tool for surgical skill acquisition, offering benefits such as improved proficiency, enhanced procedural efficiency, and reduced complications.15 Pediatric orthopedic simulation training is growing. Initiatives such as Top Gun at the International Pediatric Orthopedic Symposium (IPOS) evaluate various skills in residents,16 and also other simulation models have been developed for procedures such as supracondylar fracture management,17 pedicle screw placement in the lumbar spine,18 and correction of angular deformities,19 among others. Our study introduces a novel model and training program that enables residents with no prior experience in cast removal to acquire this skill.

The expert feedback on our model's face validity was overwhelmingly positive, with all participants agreeing that it serves as a valuable tool for teaching this technique to residents. A survey of 10 orthopedic residency programs revealed that physicians typically receive less than an hour of formal training on cast application and removal.20 Given this, we believe our model could make a meaningful contribution to addressing the gaps in training on this topic.

A novelty of our work was that we were able to include evaluation using OSATS and SRS for performance, which have not been included in previous studies.8–11 OSATS is based on the direct observation of residents or surgeons performing various surgical procedures on simulation models,14 and its reliability and construct validity have been previously demonstrated.21 Novices showed a statistically significant improvement in both OSATS and SRS. Additionally, no differences were found when comparing the final evaluations of residents to those of experts. This demonstrates that these scales are effective tools for assessing performance.

We decided to conduct only two training sessions, following the study by Ruder et al.,10 which showed that a single training session could reduce the saw temperature. However, we were unable to demonstrate significant differences in saw temperature between residents’ pre- and post-training measurements, nor when compared to experts. This may be due to the use of Paris cast in our study, while Ruder et al. used fiberglass, which could have different heat conductivity properties. Additionally, the limited sample size in our study may have contributed to the lack of observed differences.

However, our model has limitations. The small sample size (six residents and two experts) limits generalizability, and the lack of blinding may introduce bias in the evaluation. Additionally, the study used a single pre- and post-training session, and multiple sessions with averages would strengthen the results. Only one evaluator was involved; including multiple evaluators while assessing inter- and intra-rater reliability would provide more robust data. Future studies should address these limitations, increase the sample size, and incorporate more evaluators and sessions to further validate the model.

The plaster cast removal simulation model proved to be an effective training tool for residents, enabling them to achieve expert-level competency. Significant improvements were observed in OSATS and SRS scores post-training, highlighting the positive impact of the intervention on this skill and the utility of these scales for assessing performance. With further refinement, it could significantly improve resident proficiency and ultimately lead to better patient outcomes.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iii.

FundingNo funds, grants, or other support was received.

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.