Correct mechanical limb alignment is crucial in total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and is particularly difficult to achieve when the knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is associated with an extra-articular deformity (EAD). Our objective is to present a surgical option in cases of severe knee arthritis associated with an EAD (indications, mechanical planning and surgical technique), pros and cons and discuss the results with this one-stage technique.

Material and methodsWe retrospectively reviewed all cases of severe KOA associated with EAD treated surgically in our institution from 2010 to 2016. In our study, we only included cases treated via simultaneous TKA and corrective osteotomy (CO) and with a minimum follow-up period of three years. In terms of imaging, we determined the apex and angulation of the EAD as well as the modification of the mechanical parameters post-treatment. The pre- and postoperative clinical assessment was performed using the Knee Society Score (KSS).

ResultsTen patients (10 knees) underwent combined surgery (simultaneous TKA and CO). The mean age was 67.7 years and the mean follow-up period was 49.2 months. The mechanical parameters were consistently corrected in the post-operative period. The mechanical axis deviation (MAD) shifted from a mean value of 6.9cm to 0.45cm and the joint line was rendered horizontal in all cases. In none of the cases did the bone resection affect the insertion of the collateral ligaments. The mean KSS value improved from 32.3 points preoperatively to 79.4 postoperatively. There were no major complications, but there were two planning errors that did not impact upon the end result.

ConclusionsIn severe associated KOA and EAD, the combined surgical treatment proposed achieves in one stage an effective anatomical and mechanical correction which is crucial to optimise clinical results and implant durability. The surgery is complex and requires careful planning.

La correcta alineación mecánica del miembro es crucial en la artroplastia total de rodilla (ATR), y es particularmente difícil de conseguir cuando a la artrosis de rodilla (AR) se asocia una deformidad extraarticular (DEA). Nuestro objetivo es mostrar esta opción quirúrgica en casos de artrosis severa de rodilla asociada a una DEA (indicaciones, planificación mecánica y técnica quirúrgica), sus pros y contras y discutir los resultados obtenidos empleando esta técnica en un solo tiempo quirúrgico.

Material y métodosSe revisaron retrospectivamente todos los casos de AR severa asociada a DEA operados entre 2010-2016 en nuestro centro. En el estudio se incluyeron solo los casos tratados mediante ATR y osteotomía correctora (OC) simultáneas y con seguimiento mínimo de 3años. Radiológicamente se han determinado el ápex y la angulación de la DEA, así como la modificación de los parámetros mecánicos tras el tratamiento. La valoración clínica pre y postoperatoria se realizó mediante la escala Knee Society Score (KSS).

ResultadosEn 10 pacientes (10 rodillas) se realizó cirugía combinada (ATR+OC simultáneas). La edad media fue de 67,7años y el seguimiento medio fue de 49,2meses. Los parámetros mecánicos se corrigieron consistentemente en el postoperatorio. La desviación del eje mecánico (MAD) pasó de 6,9cm a 0,45cm de media y la línea articular quedó horizontal en todos los casos. En ningún caso la resección ósea invadió la inserción de los ligamentos colaterales. El valor medio del KSS mejoró de 32,3 puntos preoperatorios a 79,4 postoperatorios. No se produjeron complicaciones mayores, pero hubo dos errores de planificación sin influencia en el resultado final.

ConclusionesEn AR y DEA severas asociadas el tratamiento quirúrgico combinado propuesto consigue, mediante un único procedimiento, una corrección anatómica y mecánica eficaces, lo que es crucial para optimizar los resultados clínicos y la durabilidad del implante. La cirugía es compleja, por lo que requiere una cuidadosa planificación.

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is currently one of the most common surgical procedures in our setting and represents the “gold standard” for the treatment of advanced knee osteoarthritis (KOA), with or without associated deformity. Among the factors that influence the function and survival of the implant, achieving correct mechanical alignment of the limb is considered to be one of the most important.1 The goal of mechanical alignment of the limb should be close to 180±3°, although this is currently under discussion. In this regard, it has been suggested that both misalignment and deviation of the axes in TKA are associated with aseptic loosening and early component replacement.2–4

The need to achieve correct mechanical parameters is even more important in KOA cases where there is an intra- or extra-articular deformity that affects the mechanics of the limb.5–7 If the deformity is purely articular, both the osteoarthritis and the deformity can be treated simultaneously with TKA alone. If the osteoarthritis is accompanied by an extra-articular deformity (EAD), the most common being malunion of a fracture or the result of a previous osteotomy,8,9 treatment depends on the severity and site of the EAD. If it is mild or close to the joint line, it can be treated with TKA alone.10,11 However, if the EAD is severe, it may be too difficult and risky to achieve good mechanical correction with TKA alone.7,12 In these cases, a corrective osteotomy (CO) combined with TKA may be required to normalise the mechanical parameters of the limb in a more efficient and less risky way.

Cases of severe KOA and EAD (possible candidates for this combined treatment) are rare, accumulated experience in the literature is not significant and the indications for this treatment are not well established. From a technical point of view, there are different opinions on whether TKA and CO should be performed simultaneously9,13 or in two surgical stages.14 And there is no consensus on the fixation systems that can be used for CO.15

This simultaneous approach to the problem is a priori more complex than isolated TKA and therefore preoperative technical and mechanical planning is crucial if we are to achieve an optimal result.

We present a study of a series of patients with severe knee osteoarthritis and EAD treated by simultaneous TKA and CO at the apex of the deformity. The main objective of this study is to demonstrate this surgical option in cases of severe osteoarthritis of the knee associated with EAD (indications, mechanical planning, and surgical technique), its pros and cons, and to discuss the results achieved using this technique in a single surgical procedure.

Material and methodsWe reviewed all patients who underwent TKA for knee osteoarthritis associated with EAD and were treated with TKA between 2010 and 2016. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards recognised by the Declaration of Helsinki and Resolution 008430 of 1993, and was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee, with the informed consent of the patients who participated in the study.

Of these, only those who met the following inclusion criteria were analysed for this work: patients with KOA with associated femoral or tibial EAD and concomitant combined surgical treatment (TKA with CO). The required minimum follow-up was 3 years.

All patients were clinically evaluated using the KSS and preoperative radiological evaluation to assess joint damage (arthrosis) and to analyse and plan correction of the associated deformity. All operations were performed by the same surgical team.

Analysis of the EAD and planning of the correction (Fig. 1): This step, which is crucial in the correction process, was carried out with a simple coronal (anteroposterior) teleradiograph. In addition, sagittal radiographs were taken of the knee and the segment where the deformity was located. In some cases, the study was completed with a computed tomography scan to assess possible rotational deformities.

Main steps in the analysis of articular and extra-articular deformities (EAD) and planning of correction with a combined technique (total knee arthroplasty [TKA] with corrective osteotomy [CO]).

I. Analysis: determination of the mechanical axis (MA), its deviation (MAD), anatomical axes (AA), joint line convergence angle (JLCA), and apex of the EAD. II. Simulation of extra-articular correction with CO at the apex of the EAD. III. Correction of articular deformity and fixation of osteotomy with the joint implant (TKA).

The measurements taken in the coronal plane were the mechanical axis of the limb and its deviation (MAD), the anatomical axes proximal and distal to the EAD, and the joint line convergence angle (JLCA)5; as well as the apex of the EAD, defined as the point of intersection of the anatomical axes proximal and distal to the deformity in the coronal and sagittal planes.

At this point, we assess the degree of angulation of the EAD and the distance from its apex to the joint line, and determine the femoral and tibial cuts required for correct implant placement. In our experience, the best way to determine the necessary joint resection is to draw a line perpendicular to the mechanical axes of the femur at the level of the condyles and of the tibia at the level of the plateau.

Indication for CO: We indicate combining a CO with the TKA when the EAD requires excessive cuts to achieve a good mechanical correction (when it affects the collateral ligament insertions). This is closely related to the severity of the angulation and the distance from the EAD to the joint interline.6,7,16 In all other cases, we try to treat the osteoarthritis and deformity with TKA alone. These are usually biplanar osteotomies to correct in the coronal and sagittal axes (Fig. 2).

The next step is to simulate correction of the EAD, matching the anatomical axes after the osteotomy. This allows us to assess the effect of different types of osteotomy (opening vs. closing) on the final length of the limb, particularly in cases of previous dysmetria. We perform the simulation on printed or digital radiographs in simple editing programs, although other planning software could be used.

Finally, we plan the intra-articular correction as in other cases of primary TKA. It is necessary to choose the type and size of implant, assessing the possibility of using custom-made long stems or other types of fixation to stabilise the osteotomy. If the use of the implant's own stems for fixation of the CO is considered, we must assess their length and diameter (sometimes it is necessary to order them custom-made).

Surgical technique: The detailed surgical technique has been published by this same team17 and may be of interest as it explains the operation step by step. The first step is to perform the CO at the apex of the EAD. This can be done by extending the incision for the TKA or (if the EAD is far from the joint line) by using a lateral approach for the femur or an anteromedial approach for the tibia. We try to perform closing osteotomies, which are more stable and generate less intraoperative tension, especially if an additional rotational correction is required. Once the planned correction has been made, we provisionally fix the osteotomy with an LCP-type plate and two clamps, leaving the medullary canal open to allow definitive fixation with the prosthesis stem. Finally, the intra-articular correction and implantation of the prosthesis is carried out as in any primary arthroplasty, using manual guides or computer-assisted navigation (CAN). With CO, the diaphysis is aligned so that we can use intramedullary guides to complete the articular cuts and achieve adequate correction of the anatomical and mechanical axes and articular angles.5 To fix the osteotomy, we have always used the stem of the prosthesis itself, augmented with LCP plates temporarily or definitively when it was necessary to provide additional stability to the osteotomy. The type of implant used in all cases was a model with components cemented to the prepared surfaces and uncemented stems. Part of the autologous bone harvested from the joint incisions was used as a graft in the osteotomy.

The post-operative period was conventional for the primary TKAs in terms of recovery of mobility and muscle strength. Partial weight bearing was allowed until satisfactory consolidation of the CO was observed.

Postoperative radiological and clinical evaluation: The radiological evaluation was performed by determining the mechanical and anatomical axes on teleradiographs, as well as the angles of the joint interline with respect to these axes, in both the coronal and sagittal planes.5 The last teleradiograph for each patient was taken at a minimum follow-up of 2 years. Clinical assessment was performed using the KSS scale (before 2011).

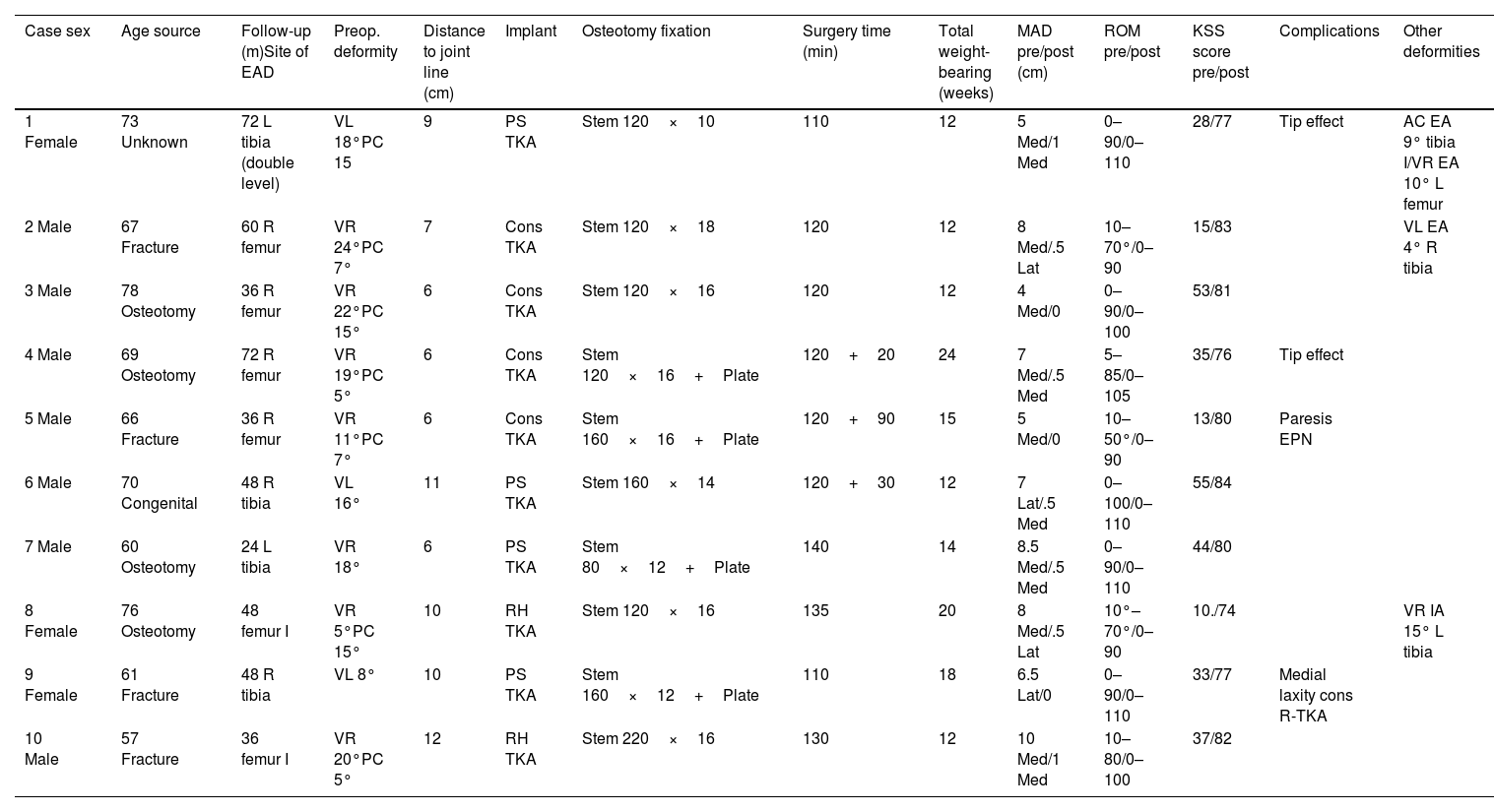

Details of the main clinical and radiological aspects and parameters assessed preoperatively and postoperatively are given in Table 1.

In this table we present the most relevant pre-and post-operative data and records from our case series.

| Case sex | Age source | Follow-up (m)Site of EAD | Preop. deformity | Distance to joint line (cm) | Implant | Osteotomy fixation | Surgery time (min) | Total weight-bearing (weeks) | MAD pre/post (cm) | ROM pre/post | KSS score pre/post | Complications | Other deformities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Female | 73 Unknown | 72 L tibia (double level) | VL 18°PC 15 | 9 | PS TKA | Stem 120×10 | 110 | 12 | 5 Med/1 Med | 0–90/0–110 | 28/77 | Tip effect | AC EA 9° tibia I/VR EA 10° L femur |

| 2 Male | 67 Fracture | 60 R femur | VR 24°PC 7° | 7 | Cons TKA | Stem 120×18 | 120 | 12 | 8 Med/.5 Lat | 10–70°/0–90 | 15/83 | VL EA 4° R tibia | |

| 3 Male | 78 Osteotomy | 36 R femur | VR 22°PC 15° | 6 | Cons TKA | Stem 120×16 | 120 | 12 | 4 Med/0 | 0–90/0–100 | 53/81 | ||

| 4 Male | 69 Osteotomy | 72 R femur | VR 19°PC 5° | 6 | Cons TKA | Stem 120×16+Plate | 120+20 | 24 | 7 Med/.5 Med | 5–85/0–105 | 35/76 | Tip effect | |

| 5 Male | 66 Fracture | 36 R femur | VR 11°PC 7° | 6 | Cons TKA | Stem 160×16+Plate | 120+90 | 15 | 5 Med/0 | 10–50°/0–90 | 13/80 | Paresis EPN | |

| 6 Male | 70 Congenital | 48 R tibia | VL 16° | 11 | PS TKA | Stem 160×14 | 120+30 | 12 | 7 Lat/.5 Med | 0–100/0–110 | 55/84 | ||

| 7 Male | 60 Osteotomy | 24 L tibia | VR 18° | 6 | PS TKA | Stem 80×12+Plate | 140 | 14 | 8.5 Med/.5 Med | 0–90/0–110 | 44/80 | ||

| 8 Female | 76 Osteotomy | 48 femur I | VR 5°PC 15° | 10 | RH TKA | Stem 120×16 | 135 | 20 | 8 Med/.5 Lat | 10°–70°/0–90 | 10./74 | VR IA 15° L tibia | |

| 9 Female | 61 Fracture | 48 R tibia | VL 8° | 10 | PS TKA | Stem 160×12+Plate | 110 | 18 | 6.5 Lat/0 | 0–90/0–110 | 33/77 | Medial laxity cons R-TKA | |

| 10 Male | 57 Fracture | 36 femur I | VR 20°PC 5° | 12 | RH TKA | Stem 220×16 | 130 | 12 | 10 Med/1 Med | 10–80/0–100 | 37/82 |

AC: antecurvatum; Cons: constrained; EAD: extra-articular deformity; EPN: external sciatic popliteal nerve; IA: intra-articular; KSS: Knee Society Score; L: left; Lat: lateral; m: months; MAD: mechanical axis deviation; Med: medial; PC: procurvatum; PS: posterior stabilised; R: right; RH: rotating hinge; R-TKA: revision TKA; TKA: total knee arthroplasty; VL: valgus; VR: varus.

Of all the patients with KOA-associated EAD initially evaluated, only 10 (10 knees) were treated with simultaneous TKA and CO and had a minimum follow-up of 3 years and were therefore included in this study. The remainder were treated with isolated TKA or had a follow-up of less than 3 years and were excluded. The mean follow-up was 49.2 months (range 36–72 months).

Of the patients included, 7 were men and 3 were women, and the mean age at surgery was 67.7 years (range 60–78). The cause of the EAD was malunion of the fracture (4), failed osteotomy (4), constitutional (1), and unknown (1), and its site was femoral in 6 cases and tibial/fibular in 4. All but 2 cases had an EAD greater than 15° and only 1 less than 10°. The EAD was monoplanar, in the coronal plane in 3 cases and multiplanar in 7 cases, and the distance from the EAD to the joint interline varied between 6 and 12cm (mean 8.3cm).

In terms of the type of joint implant used, 4 knees had a constrained TKA, 4 had a posterior stabilised (PS), and the remaining 2 had a rotating hinge (RH) TKA. In all cases, stem prostheses were used, at least in the deformed segment, not only to improve fixation to the bone but also to stabilise the osteotomy. In our opinion, the implant stem should overlap the CO by at least 15–20cm. If this is not possible, we recommend augmentation with an LCP plate. The corrective osteotomy was performed at the apex of the EAD in all cases and the angulation (anatomical axis) was fully corrected in all cases without any significant difficulty. In 4 of the 10 cases, it was considered necessary to increase the fixation of the CO with a plate to improve its stability. The osteotomy was an opening osteotomy in 3 cases and a closing osteotomy in the remaining cases. The CO was monoplanar in cases where the deformity involved only the coronal plane – 3 cases – and biplanar in the rest. It was not necessary to use offset stems in any of the cases.

The average duration of surgery was 136min (110–210min), with double tourniquet to the limb required in 3 knees. Consolidation was achieved steadily and the mean time to full weight bearing was 15.1 weeks (12–24 weeks).

After extra- and intra-articular correction (Fig. 3), MAD improved significantly from a preoperative mean of 6.9cm (4–10cm) to .45cm (0–1cm) postoperatively. In 6 cases, preoperative limb length discrepancy (LLD) was noted in the affected limb, with partial correction of the dysmetria after angle correction.

68-Year-old male. (A) Post-fracture osteoarthritis of the right knee. Distal femoral varus extra-articular deformity (EAD) of 24°. Excessive distal femoral resection necessary, invading the insertion of the lateral ligament. Tibial diaphyseal valgus EAD of 4°. (B) Postoperative situation after combined technique (TKA+CO). The slight lateralisation of the MA is due to the tibial EAD, which was considered acceptable. (C) 3.5 years post surgery.

Clinically, patients experienced significant improvement after this surgery. In terms of range of motion (ROM), the postoperative situation improved significantly compared to the preoperative situation, from a mean value of 77° (40°–100°) to 101.5° (90°–110°), with a notable change in knee extension capacity in 5 cases. The overall clinical assessment of these patients showed a significant positive change from a mean KSS of 32.3 points (13–55) to 79.4 points (74–84) in the post-operative period.

In terms of complications, in one case the implant we used was not able to control the previous medial instability and it was necessary to replace it with another RH-type implant with good results. We should also mention the postoperative pain in 2 patients, probably due to the “tip” effect of the stabilising stem of the osteotomy, which disappeared in both cases 6 and 12 months after the operation. In the first case, the femoral stem chosen was too thin and did not fit properly in the medullary canal (Fig. 4). Therefore, despite the increased fixation with a plate, it seems that the osteotomy was not properly stabilised, facilitating the end of the stem hitting the external femoral cortex. In the second case, there was also pain due to the tip effect, but in this case due to a planning error, since the deformity, which was bifocal, was corrected only in the coronal plane (Fig. 5). As a result, the end of the tibial shaft came into contact with the anterior tibial cortex, causing pain which disappeared spontaneously 12 months after the operation. Also worth mentioning is a case of paresis of the external sciatic popliteal nerve, which recovered spontaneously in a patient with distal femoral EAD, in whom the operation required 2 episodes of controlled ischaemia for a total of 210min. There were no major complications (non-unions, infections, thromboembolism, or component loosening, etc.) that could have affected the final outcome of the surgery. The results obtained in this series of patients are detailed in Table 1.

72-Year-old female. (A). Left knee osteoarthritis (KOA). Diaphyseal tibial valgus DEA of 18° secondary to bone dysplasia. (B) Postoperative X-rays after correction with combined technique (TKA+corrective osteotomy). Tip effect (arrow) due to uncorrected distal diaphyseal deformity in procurvatum. (C) AP telemetry at 4-year follow-up.

In knee replacement surgery, there seems to be a general consensus on the importance of achieving the correct mechanical situation in the lower limb for a TKA to achieve adequate functionality and longevity.9 This goal could be summarised as achieving a mechanical axis without deviation and a stable joint with a horizontal interline.

We agree with other authors5,8 that the indication for performing a CO at the level of the EAD is essentially determined by the bone resection required to achieve good joint alignment and limb orientation. Bone resection is directly related to the severity of the EAD, and we consider it excessive if it compromises the ligament insertions and therefore postoperative joint stability.6,7 In our experience, EAD values greater than 15°–20° (coronal/sagittal) are associated with excessive articular bone resection and we therefore recommend combined treatment (TKA+CO) in these cases. In the case of small EADs, the resection required for correction is less and is less likely to affect joint function. Therefore, if the EAD is less than 10°–15°, we try to correct it with TKA alone.7,16

The mechanical planning of the correction must be complete but simple. The key determinants are the mechanical axis of the limb and its deviation, the proximal and distal anatomical axes of the EAD, its apex, and the articular cuts.

With regard to the surgical technique, there are several points that can be discussed.12,13,18,19 The first is the guidance system used to implant the prosthesis. In general, in these complex cases of OA associated with EAD, we agree with the advisability of using CAN systems whenever possible. This recommendation is particularly important in cases where it is decided not to correct the EAD, as manual guidance will be difficult and/or less reliable.20 The location of the CO should ideally be at the apex of the deformity, otherwise it will create a double deformity and/or undesirable axis shift and compromise intramedullary fixation.21,22 In all our cases, correction of the EAD was acute, using the stem of the prosthesis itself to fix the osteotomy. This stem was always straight and of the existing diameter, although in 3 cases it had to be ordered because of its thickness. Acute correction of EAD in our series was possible without difficulty and was not the cause of neurovascular complications. We believe that progressive correction would be advisable in very severe deformities and/or deformities where acute correction is risky (valgus and/or procurvatum of the proximal tibia). In these cases, it may be advisable to perform a progressive correction of the deformity5 and to implant the TKA in a second stage. The use of the prosthesis stem to fix the CO is a very useful tool and has several advantages over other fixation methods: it is part of a single implant and, if a good fit is achieved, it is very stable, even against rotation, without the need for additional fixation.12,13 This assumes that the correction has been made at the apex and that the EAD is not too far from the joint. We believe that osteotomies closer to the metaphysis (less tubular bone) may be candidates for additional fixation with a plate,18 especially if they are opening (less stable) (Fig. 3). If we choose an opening CO we can improve a possible pre-existing length discrepancy.

The choice of implant type does not differ from that of other primary TKA, except in the use of long stems to stabilise the CO. Except in 4 cases of tibial EAD in which we used PS TKA, in the rest we used constrained models in 4 cases, and even RH-type models in another 2 with previous instability. If the peripheral ligaments are intact, it would not be necessary to use constrained or hinged implants,9 but in our implants the femoral component with stem is necessarily constrained.

The alternative to the combined treatment that we advocate is correction using TKA alone (Fig. 6), preferably using CAN.11,20,23 Cases treated with personalised prostheses have recently been published, which may be another option in these cases.24 With both techniques the correction can be very precise, but the combined technique has a series of advantages: the main being that it requires less bone resection and, therefore, less risk to the postoperative ligament balance,7 correcting the anatomical axis of the segment and facilitating intramedullary fixation.12 Furthermore, we are not aware of any reports in the literature on the importance of a correct anatomical axis, but it is reasonable to think that the more the operated bone resembles a normal one, the better its mechanical behaviour will be. The main disadvantage of the combined technique is the greater technical complexity and, consequently, surgery time. Minimising this fact requires meticulous preoperative planning. The clinical results (pain and functionality) coincide with those of other published series12,25,26 and this is yet another reason to recommend the use of the proposed combined technique.

Correction of severe knee osteoarthritis+extra-articular deformity (EAD) by total knee arthroplasty (TKA) alone. Disadvantages compared to the combined technique (TKA+corrective osteotomy). I. Greater bone resection putting previous stability at risk. II. Uncorrected anatomical axes. Greater difficulty or impossibility of using stems in the implant.

With the exception of the medial instability case, which required implant replacement, there were no complications in the other cases presented that compromised the outcome. The two cases of planning errors resolved spontaneously. These errors reinforce the idea of the importance of prior planning, in this case regarding the implant and fixation to be used. To avoid the most common problems in osteotomies (non-unions and refractures), we recommend aiming for complete correction of the EAD, using stable fixation methods and avoiding unnecessary tissue damage. Other series have reported complications such as deep infections, non-unions at the CO level or arthrofibrosis,26,27 which are not surprising in this type of complex surgery.

This study has many limitations. It is obviously a short, heterogeneous series studied retrospectively, which limits the value of the results. However, these are unique cases for which the proposed solution may be very useful when faced with these situations.

ConclusionsIn associated severe KOA and EAD, the proposed combined surgical treatment achieves an effective anatomical and mechanical correction, which could be crucial for optimising clinical results and implant durability.

The stem of the implant itself, when correctly selected, has been shown to be effective in achieving satisfactory fixation of the osteotomy.

The surgical procedure is complex and requires careful planning, both in terms of angle correction and implant selection.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iv.

Ethical considerationsThe present study did not involve animal or human experimentation and does not contain personal data, in accordance with ethical standards for research and publication.

FundingNo specific support from public sector agencies, commercial sector, or not-for-profit organisations was received for this research study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

![Main steps in the analysis of articular and extra-articular deformities (EAD) and planning of correction with a combined technique (total knee arthroplasty [TKA] with corrective osteotomy [CO]). I. Analysis: determination of the mechanical axis (MA), its deviation (MAD), anatomical axes (AA), joint line convergence angle (JLCA), and apex of the EAD. II. Simulation of extra-articular correction with CO at the apex of the EAD. III. Correction of articular deformity and fixation of osteotomy with the joint implant (TKA). Main steps in the analysis of articular and extra-articular deformities (EAD) and planning of correction with a combined technique (total knee arthroplasty [TKA] with corrective osteotomy [CO]). I. Analysis: determination of the mechanical axis (MA), its deviation (MAD), anatomical axes (AA), joint line convergence angle (JLCA), and apex of the EAD. II. Simulation of extra-articular correction with CO at the apex of the EAD. III. Correction of articular deformity and fixation of osteotomy with the joint implant (TKA).](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/18884415/0000006900000004/v2_202507070624/S1888441525000700/v2_202507070624/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)