Synthetic biomaterials obtained through tissue engineering offer an alternative to the use of autologous and heterologous grafts for the repair of bone defects of various etiologies, although the ideal material for this purpose has not yet been developed. A gel based on chitosan (CS) (3-glycidoxypropyl)trimethoxysilane (GPTMS), and silica have shown efficacy in experimental studies from a biomechanical and in vitro osseointegration perspective.

ObjectiveTo demonstrate that the hybrid aerogel based on CS-GPTMS-silica is effective and safe for treating bone defects in load-bearing bone in rabbits.

Materials and methodsA comparative experimental study was conducted on 12 adult New Zealand rabbits, involving osteotomy in both radii as case (osteotomy with biomaterial placement) and contralateral control (osteotomy with placement of the extracted bone), both fixed with plates and screws. After 10 weeks, the animals were euthanized, and the surgical area was subjected to histological analysis.

ResultsFor all subjects, wound healing was successful, and normal gait was observed within 24–48h. In case limbs, cortical closure of 95.9% was observed compared to 98% in control limbs. Residual biomaterial was observed in 5 subjects, with an average of 16% of the total analyzed area. Inflammatory cells were grouped (5–10%) in all case samples, with significant differences between case and control samples (p<.05). An increase in the presence of bone precursor cells (5–10%) was observed in all case samples compared to control samples, with significant differences (p<.05).

ConclusionsThe aerogel based on chitosan CS-GPTMS, and silica is biocompatible and safe in rabbits, demonstrating minimal inflammatory reaction, good osteoblast adhesion, and a high resorption rate.

Los biomateriales sintéticos obtenidos mediante ingeniería tisular ofrecen alternativa al uso de injertos autógenos y heterólogos para la reparación de defectos óseos de diferente etiología, si bien aún no existe el material ideal para este fin. El gel a base de quitosano (CS) (3-glicidoxipropil)trimetoxisilano (GPTMS) y sílice ha demostrado su eficacia en estudios experimentales desde el punto de vista biomecánico y osteointegración in vitro.

ObjetivoDemostrar que el aerogel híbrido a base de CS-GPTMS-sílice es eficaz y seguro en el tratamiento de defectos óseos en el hueso sometido a carga en el conejo.

Material y métodoSe ha realizado un estudio experimental comparativo en 12 conejos adultos Nueva Zelanda, mediante osteotomía en ambos radios como caso (osteotomía y colocación del biomaterial) y control contralateral (osteotomía y colocación del mismo hueso extraído), ambas fijadas con placa y tornillos. A las 10 semanas se realizó la eutanasia de los animales y el estudio histológico de la zona quirúrgica.

ResultadosEn todos los animales la cicatrización de la herida fue correcta y la marcha era normal a las 24-48h. En las patas caso, se observó el cierre cortical del 95.9%, frente al 98% en las patas control. Los restos de biomaterial remanente fueron observados en 5 sujetos, con una media de un 16% respecto al total de corte observado. En todas las muestras caso hubo presencia de células inflamatorias agrupadas (5-10%) siendo la diferencia significativa entre las muestras casos y controles p<0,05. En todas las muestras caso hubo aumento de la presencia de células precursoras óseas (5-10%) respecto a los controles con significación p<0,05.

ConclusionesEl aerogel a base de CS-GPTMS y sílice es biocompatible y seguro en conejos, demostrando escasa reacción inflamatoria y una buena adherencia de los osteoblastos, así como una alta tasa de reabsorción.

Bone substitutes are currently frequently used in the field of orthopaedic surgery to repair defects of various aetiologies (fractures, tumours, congenital deformities, infectious diseases, and prosthetic and rescue surgery, among others1,2).

The progressive ageing of the population and the poor bone quality associated with advanced age, and increased life expectancy and quality of life expectancy, have led to an increase in demand for these bone substitutes in trauma surgery, representing a significant and growing economic burden to the healthcare system. The problem of graft availability for this type of surgery has led, in recent years, to the search for biomaterials designed as bone substitutes that can accurately simulate the characteristics of human bone.1–5

The key properties of biomaterials include structure, roughness, porosity, specific surface area, mechanical properties, and chemical functionality that facilitate biointegration into the system, and actively contribute to the restoration or improvement of the surrounding bone tissue.2–9

Current artificial bone substitutes include ceramics (such as hydroxyapatite and calcium phosphate), biodegradable polymers, bioinert metals, hybrid biomaterials, and bioactive gels. These are designed to mimic the structural, mechanical, and biological properties of natural bone, in order to promote bone regeneration and functional integration. Gels have been widely studied as pure or hybrid materials, because one advantage of these materials is that their properties can be adjusted by selecting appropriate constituent phases and controlling their relative content.3 Additionally, adding organic polymers in controlled amounts allows the mechanical properties of these bioactive hybrid aerogels to be adjusted, such as porosity, mechanical strength, etc. Furthermore, biomaterials used for bone regeneration must promote osteoblast adhesion, mineralised matrix neogenesis, and the formation of new bone tissue.2–9

Currently, there is no biomaterial available with the above-described characteristics. Therefore, a combination of sol–gel technology has been proposed to produce bioactive glass-based biomaterials.

The research group has developed a gel based on based on chitosan (CS) (3-glycidoxypropyl)trimethoxysilane (GPTMS) and silica that has proven effective in in vitro experimental studies.9 This experimental study in animals aims to demonstrate the safety and effectiveness of the hybrid aerogel in the treatment of bone defects in weight-bearing bones in rabbits.

Material and methodStudy designPreliminary experimental study designed to evaluate the methodological feasibility and safety of a biomaterial in an animal model. This involves comparing the efficacy of the biomaterial with the gold standard (autograft) in bone regeneration, using an intra-individual controlled design, whereby the same animal serves as both case and control. The intervention involves performing an osteotomy in the radius diaphysis to implant the biomaterial and autograft in contralateral limbs, allowing for an initial comparative analysis with a small sample size.

BiomaterialThe selected biomaterial is a hybrid CS-GPTMS-mesoporous silica aerogel developed by the Department of Condensed Matter Physics at the University of Cádiz, protected by patent number ES2935742B2. In the preliminary study to select the material, 10 hydrogels with the same base composition but different percentages of CS and GPTMS were prepared.9 One of the samples was selected following mechanical and laboratory testing (immersion in simulated physiological saline and osteoblast culture), with very favourable results for use as a substitute material for bone tissue regeneration: CS10G4 (Fig. 1).

Animal modelTwelve adult New Zealand white rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) were used for the study. They weighed approximately 2500–3500g at the start of the study and were between 28 and 32 weeks old, ensuring physeal closure and completion of bone growth. All rabbits used were male.

Environmental conditions remained constant throughout the study, with a programmed photoperiod of 12-h light-dark photoperiod (350lux/m2). The temperature was also kept stable, between 22°C and 24°C, with constant humidity between 55±10%. All animals had free access to water and standard commercial rabbit feed. Each specimen was identified by different colours (non-toxic and biodegradable dye) marked on the ears and the corresponding cage.

The animal study was approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of the University of Cádiz and by the Regional Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries and Sustainability, in accordance with Article 26.1 of Decree 622/2019. The European Union regulations for the protection of animals used in experiments (EU/63/2010) and the ARRIVE 2.0 guidelines10 were followed throughout the handling of the animals. The Central Production and Experimentation Services of the University of Cádiz (farm registration code: ES110120000210) were responsible for both the stay of the animals and the surgeries. All personnel with access to the animals were certified to handle them: a (animal care) for the centre's carers and A, B (euthanasia), and C (carrying out procedures) for the surgeons.

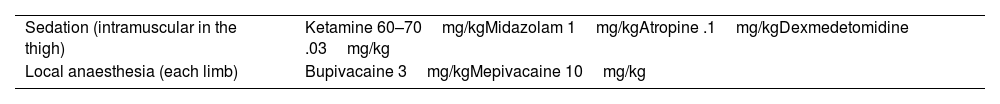

SurgeryThis was performed under aseptic conditions, sedation (ketamine, midazolam, atropine, and dexmedetomidine) and local anaesthesia (mepivacaine and bupivacaine) (Table 1).

A dorsal incision of approximately 4cm was made on the middle third of the radial bone diaphysis of both forelimbs, in line with the third and fourth toes. An osteotomy approximately 10mm long and 6mm thick was then performed on both forelimbs (Fig. 2). Next, the selected CS10G4 material was placed in one forelimb, with the same bone fragment placed in the other forelimb but with the cranial-caudal polarity reversed. This meant that the same animal could serve as both case and control.

Both the biomaterial and the autograft were then fixed to the remaining bone using a 6-hole 1.5mm locking compression plate (LCP), with two 1.5mm×8mm cortical screws on each side of the graft (Fig. 2).

After completion of the surgery, the animals were moved to a quiet, warm area until fully awake (spontaneous active mobility). For post-operative analgesia, meloxicam .2mg/kg and buprenorphine .03mg/kg were administered subcutaneously. Ampicillin 7mg/kg was administered subcutaneously for antibiotic prophylaxis.

All the rabbits were assessed on the first post-operative day and then weekly until the 10th week. Pain was assessed using a simple descriptive scale and a facial expression scale.11

The animals were euthanised 10 weeks after surgery using the same sedation as used in the operation (Table 1) and an overdose of sodium thiopental was administered intraperitoneally at a dose of 200mg/kg. The death of each animal was confirmed by exsanguination through sectioning of the carotid artery.

All experimental procedures were carried out at the Central Animal Production and Experimentation Service in Cádiz.

Histological studyThe fragment of material and bone around it was extracted en bloc by meticulous dissection of soft tissues. The plate and screws were then removed.

For bone decalcification and subsequent handling, the samples were fixed in 10% formalin for at least 72h, after which they were decalcified in 3% nitric acid for seven days. The formalin–nitric acid dilution was changed twice during this process. Bone block samples approximately .5cm in length were obtained from the regions of interest (A) bone/scaffold interface to demonstrate integration and (B) the intermediate zone of scaffold introduction to assess bone neoformation. The two sections from each bone sample were processed overnight in a Leica HistoCore Pegasus Plus tissue processor (Nussloch, Germany) for paraffin embedding. The following day, the sample blocks were prepared for cutting and staining with haematoxylin and eosin.

The following special stains were also performed:

- -

Van Gieson (picrofuchsin): stains collagen fibres green or blue-green, bone tissue purple or orange, the osteoid matrix yellow, and muscle fibres blue. This allows distinction to be made between non-mineralised osteoid and mineralised tissues.

- -

Immunomarking with CD68 for the identification of inflammatory tissue (polymorphonuclear cells).

The following variables were collected.

During the surgical phase: the percentage of closure of cortical circumference, the percentage of biomaterial remaining in relation to the total cut, the presence of inflammatory cells, the percentage of inflammatory cells/total cells observed, the presence of osteoblasts/osteocytes, and the percentage of osteoblasts/total cells observed. Both inflammatory cells and osteoblasts were considered positive samples for their presence if they showed accumulation or areas of greater activity; dispersed inflammatory cells or bone precursors were considered normal.

In the histological analysis phase, the following variables were collected: sex and weight of the animal at the time of surgery; surgical time per limb (A=case, B=control); notable incidents during surgery; incidents during the first 6 visits (24h post-surgery and 48h post-surgery, first, second, third, and fourth weeks, and weeks five to ten); notable incidents during euthanasia and whether there were findings of macroscopic consolidation.

Statistical modelThe descriptive statistical study analysed the collected variables, differentiating between quantitative and qualitative variables. Measures of central tendency such as the mean, median, and mode were used for quantitative variables, while absolute and relative frequencies were used for qualitative variables, providing a comprehensive view of the distribution and behaviour of the data.

Qualitative variables were compared using the χ2 test. Quantitative variables were compared using ANOVA. The influence of the association between the determined quantitative parameters was evaluated using Pearson's correlation coefficient. Paired analysis between variables was performed using the Wilcoxon test. The significance level was set at 95% (p<.05).

As the same animal served as both case and control, the samples were treated as homogeneous.

ResultsSurgery and euthanasiaBetween March and August 2023, 12 rabbits underwent surgery. Their average weight at the time of surgery was 2850g (2700–2900). The average duration of the surgery was 37min (19–45). The animals woke up spontaneously between 30 and 60min after the surgery ended.

At 24h post-operatively, all the rabbits were walking with mild lameness, except for one that presented significant lameness mainly in the case limb (A), which was given another dose of analgesic. Another rabbit died 24h after the surgery, having remained practically immobile during that time. The remaining rabbits had a favourable outcome in terms of the surgical site. Two rabbits all had mild inflammation of the affected limb, which resolved spontaneously by one-week follow-up. One of these rabbits required new wound sutures at the 24-h post-operative visit. There were no signs of infection at the surgical site in any case. Complete wound healing was observed in all the rabbits between days 7 and 14.

All euthanasia was performed at week 10 or week 10 and one day. At the time of euthanasia, all the rabbits were living normal lives, with no signs of pain, lameness, or other behavioural or feeding abnormalities.

During the extraction surgery, two animals presented bone growth above the plate in both limbs. Both the cases and the controls presented complete closure of the bone defect (Fig. 3). The most frequent finding was radioulnar synostosis, which occurred in 6 of the 11 animals that completed the observation period. This led to a fracture of the radius in 2 of the control animals when the radius and ulna were separated, although the fracture occurred distal to the surgical site.

HistologyIn the case limbs, the average percentage of closure of the cortical circumference in the central sections was 94.5±8%. In the samples from the periphery of the surgical area, the percentage of closure was 96.4±8%. In the control limbs, 98% cortical closure was observed. This difference was not statistically significant p>.05% (Fig. 4).

In the samples from the centre of the surgical area, biomaterial remnants were visible in 5 case samples, accounting for an average of 16% of the total section (Fig. 5). In the peripheral samples, they were visible in 2 of the 11 rabbits that completed the study, both with 10% of biomaterial remaining with respect to the total section.

In all case samples, there were clusters of inflammatory cells: in 5 of them, both in the samples from the centre and in the sample from the periphery, in 3 only in the centre and in 3 only in the periphery, with a significant difference between the case and control samples (p<.05). In all of them, the percentage of inflammatory cells was between 5% and 10% of the total cells observed (Fig. 5A). Clustered inflammatory cells were visible in only one of the control limbs, in the centre sample.

Similar to inflammatory cells, in all case samples there was an increase in the presence of bone precursor cells (between 5% and 10% osteoblasts and osteocytes) compared to the control samples, with a significance of p<.05. This was similar in the central and peripheral samples (Fig. 5B). Only in one of the control limbs was an increase in osteoblasts and osteocytes observed, in the central sample.

DiscussionThe study evaluated the biocompatibility and efficacy of a hybrid aerogel based on CS-GPTMS and silica in rabbits. Its performance was compared with that of bone autografts through histological analysis and clinical observations over 10 weeks. The study concluded that the biomaterial is safe, with good bone integration, and low inflammatory reaction.

The main difference between the initial compounds regarding the selected biomaterial was the GPTMS content. The G value refers to the [GPTMS]/[CS monomer] ratio, which was 4 in this case. The final CS percentage is 9.7%. GPTMS provides greater density, thereby achieving a stronger network. CS10G4 also has high porosity (82.3%, comparable to cancellous bone porosity of 79.3%9,12–14) and a pore size of 11.6nm, which are large enough to allow fluid flow within the pores and thus stimulate osteocytes.11 In the mechanical analysis, the maximum stress supported was much higher for the CS10G4 sample, which had the highest amount of GPTMS. The same was true for Young's modulus.9,14 Furthermore, this biomaterial exhibited favourable osteoblast adhesion in vitro culture in previous studies9 (Fig. 6).

HOB® osteoblasts cultured in the CS10G4 sample after 48h (A and B), 72h (D and E), and 1 week (G and H) in culture and examined with a confocal microscope (40×). Osteoblasts cultured on glass were used as a reference control, shown in (C), for 48h in culture (F), after 72h in culture and (I) after 1 week. In red, actin cytoskeletal fibres immunolabelled with rhodamine phalloidin show the polarisation of the material and the arrangement of the actin cytoskeleton in tension fibres. Focal adhesions (yellow) were immunolabelled with anti-vinculin antibody. Nuclei (blue) were labelled with DAPI.

In terms of the surgical model, the radial diaphysis in rabbits was chosen for the design and location of the graft because it is an accessible bone that bears axial loads. Furthermore, this model allows for the creation of small samples that are still large enough to handle and easily reproducible. With this model, it was also possible to create a large bone defect in a weight-bearing bone.14–17

Rabbits were selected as the animal model because they are more closely related to primates than rodents and because their Haversian system and bone metabolism resemble those of humans. Rabbits also have less cancellous bone and more fragile cortical bone, meaning that good outcomes in rabbits would be expected to translate into better outcomes in humans.10 However, the main disadvantage of rabbits is the difficulty in manipulating small bones (approximately 6cm in length of the entire radius×approximately 9mm in diameter of the bone), so in the first two surgeries, the biomaterial cylinders had to be carved intraoperatively to reduce their size. This issue was resolved for subsequent surgeries by carving the cylinders beforehand.

The surgical time was significantly longer for the first four animals, due to the surgeons’ inexperience and the aforementioned issues with carving the biomaterial cylinders (an average of 50min compared to an average of 30min for the rest). The case that did not complete the observation period due to death within the first 24h was the second animal operated on. The animal did not fully regain consciousness, and possible causes of death include excessive bleeding during the operation or an underlying disease. It is not believed that this was due to the material, given the short time between its placement and the animal's death, as well as the absence of significant inflammatory findings at the surgical site. The animal that presented bone growth above the osteosynthesis plate was the first animal to undergo surgery which could have been due to the excision of the bone fragment including all the cortices and, therefore, a larger bone callus.

In terms of the histological study, the cortical circumference was practically completely closed in all case limbs. The percentage of inflammatory cells in the cases was relatively low, and therefore 10 weeks after surgery there did not appear to be a significant inflammatory response. However, it was somewhat higher than in the control limbs, as expected given the time elapsed. Furthermore, this type of cell was mainly present in areas where bone had not yet formed or around the biomaterial remnants (Fig. 5A). A similar pattern was observed with bone precursor cells, which were predominantly found around cortical closure defect area (Fig. 5B).

These characteristics suggest clinical benefits of using this biomaterial in bone reconstruction surgery, due to its rapid manufacture, ease of intraoperative handling, osteointegration and resorption rates, and low inflammatory response. It could be used to cover bone defects of various sizes, either with or without additional fixation by osteosynthesis.

One of the strengths of this study is the originality of the sample, which was patented and developed by the University of Cádiz. Another strength is the low production cost of the biomaterial. Furthermore, the components of the aerogel can be modified to make it 3D printable and, given its ease of handling it can be used for cultivating mesenchymal cells. Future studies could involve increasing the evolution time, or different times, since in some cases the incomplete resorption of the biomaterial, the partial closure of the cortex, and ongoing inflammatory reactions could be due to the early stages of biomaterial integration in bone formation.18 Another possible improvement to the study would be to carry out various studies to assess the radiological osseointegration of the biomaterial using imaging tests such as plain radiography or computed tomography.19,20 Finally, one of the main limitations of this study is the small sample size.

In conclusion, this preliminary study shows that CS-GPTMS and silica-based aerogel is biocompatible and safe in rabbits, with little inflammatory reaction and good bone integration, as well as a high resorption rate. Further studies in other bone defect models are needed.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence I.

Ethical considerationsThis animal study was approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of the University of Cádiz and by the Regional Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries, and Sustainability, in accordance with Article 26.1 of Decree 622/2019.

Throughout the handling of the animals, the rules established by the European Union for the protection of animals used in experiments (EU/63/2010) were followed at the Central Production and Experimentation Services of the University of Cádiz (farm registration code: ES110120000210), as well as the ARRIVE 2.0 guidelines. Percie du Sert N et al., 2014.

FundingThis study was funded by the Spanish Society of Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology (SECOT) Foundation: Grant for Research Initiation Projects (year 2021).

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

To the Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology, Rheumatology and Pathological Anatomy Services of the Puerta del Mar University Hospital, and to the Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology and Clinical Pharmacology Services of the Puerto Real University Hospital. The Institute for Biomedical Research and Innovation of Cádiz (INiBiCa).