The calcaneonavicular ligament (spring ligament) plays a fundamental role in calcaneonavicular static stability and medial longitudinal arch, injury which is related to flatfoot.

ObjectiveThe primary objective was to compare the biomechanical behaviour of the spring ligament in a healthy foot and after section and repair with augmentation and transfer of the flexor digitorum longus (FDL). As secondary objectives we have the biomechanical comparison between isolated repair with augmentation associated or not with transfer.

MethodsThis experimental biomechanical cadaver study evaluates the medial complex in four phases: intact ankle (1); spring injury (2); repair and augmentation (3), and after FDL transfer (4). Talonavicular angular displacement was measured in the three planes of space using an arthrometer and manual spring ligament exploration manoeuvres.

ResultsSignificant differences were found after sectioning the ligament with the abduction and external rotation manoeuvre in the coronal (p=.050) and sagittal (p=.045) planes. Upon augmentation, there was significance in the horizontal plane (p=.047) and after FDL transfer in the horizontal plane (p=.002). However, no significant differences were identified between repair and augmentation and FDL transfer.

ConclusionLigament section generated instability in the coronal and sagittal plane with abduction and external rotation movements. It should be noted that both surgical techniques were able to restore joint stability, even surpassing that achieved with the ligament intact.

El ligamento calcaneonavicular (spring ligament) juega un papel fundamental en la estabilidad estática calcaneonavicular y el arco longitudinal medial, cuya lesión se relaciona con el pie plano.

ObjetivoEl objetivo principal fue comparar el comportamiento biomecánico del ligamento calcaneonavicular en un pie sano y tras la sección y reparación con aumentación y transferencia del flexor común de los dedos (FCD). Como objetivo secundario se estudió la comparación biomecánica entre la reparación aislada con aumentación asociando o no la transferencia.

Material y métodoEste estudio biomecánico experimental en cadáver evaluó el complejo medial en cuatro fases: tobillo intacto (1); lesión del ligameno calcaneonavicular (2); reparación y aumentación (3), y tras la transferencia del FCD (4). Se midió el desplazamiento angular talonavicular en los tres planos del espacio mediante un artrómetro, aplicando maniobras manuales de exploración del ligamento de calcaneonavicular.

ResultadosSe encontraron diferencias significativas una vez seccionado el ligamento con la maniobra de abducción y rotación externa en los planos coronal (p=0,050) y sagital (p=0,045). Al realizar la aumentación, hubo significación en el plano horizontal (p=0,047) y tras la transferencia del FCD en el plano horizontal (p=0,002). Sin embargo, no se identificaron diferencias significativas entre la reparación y aumentación y la transferencia del FCD.

ConclusiónLa sección del ligamento generó inestabilidad en el plano coronal y sagital con movimientos de abducción y rotación externa. Ambas técnicas quirúrgicas lograron restaurar la estabilidad articular, incluso superando la alcanzada con el ligamento intacto.

Recently, significant changes have occurred regarding the aetiopathogenesis, concept, and classification of acquired adult flatfoot, a topic that generates considerable controversy. Currently, the term “flatfoot” has become obsolete, having been replaced by the term “Progressive Collapsing Foot Deformity” (PCFD).1 This new nomenclature places greater emphasis on the progressive, multifactorial, and multiplanar nature of the deformity, recognising the primary role of soft tissues and the correct alignment of the midfoot, hindfoot, and ankle in the development of the condition.2 The Johnson and Strom classification, proposed in 1989, laid the foundation for understanding the deformity as a direct consequence of dysfunction and eventual rupture of the posterior tibial tendon. While this view was later expanded upon by authors such as Myerson in 1997 and Bluman in 2007, the model continued to be based on a linear progression of stages, without adequately considering the true complexity of the condition. Over time, it has become clear that adult flatfoot deformities do not always progress sequentially, and that different compartments of the foot and ankle can be affected simultaneously or independently. This more nuanced understanding has driven the need for a new nomenclature that allows for a more precise and functional description of clinical and radiographic findings, without being limited to a rigid classification by stages.3

Although it has generally been accepted that posterior tibial muscle dysfunction was the fundamental cause of the development of progressive flatfoot collapse due to its important role as a dynamic stabiliser, this view is regarded as highly simplistic. This has led to the three-dimensional conception of the deformity, suggesting that the development of collapse is much more than mere posterior tibial muscle rupture.4–7 The calcaneonavicular ligament is directly involved as a kinetic conduction element, facilitating movement and connection between the hindfoot and forefoot. This functional role has gained importance in recent years, with recognition of its potential to stabilise the medial longitudinal arch, contributing to maintaining its structure and statically stabilising the talar head and talonavicular joint during the different phases of gait.8,9

The calcaneonavicular ligament, or spring ligament (SL), is a complex unit consisting of three main components: the inferoplantar, midplantar, and superomedial calcaneonavicular ligaments.10 Clinical suspicion of an isolated calcaneonavicular ligament injury arises when there is persistent pain on the medial aspect of the foot. The typical mechanism that causes this injury is landing and hindfoot eversion, resulting in a unilateral deformity.9 Moreover, recent anatomical studies suggest that the calcaneonavicular and deltoid ligaments are not isolated anatomical entities, but rather form a large ligamentous complex, the tibiocalcanealavicular ligament or tibiospring, which acts as a functional unit, with each ligament retaining its specific function. The deltoid ligament provides the primary restraint against tibiotalar valgus and external rotation of the talus.

The role of the calcaneonavicular ligament in the development of medial column collapse and talonavicular depression has been little studied. Recent biomechanical studies have provided information on the importance of the calcaneonavicular ligament in maintaining the plantar arch and restricting pronation during the different phases of gait.9,11,12

Reconstructive techniques such as repair and augmentation with high-strength devices, as well as transfers, have been progressively added to the treatment algorithm for flexible flatfoot. These techniques have become an addition to standard procedures such as medial calcaneal glide or lateral column lengthening.5,13,14

This study aimed to compare the biomechanical behaviour of the calcaneonavicular ligament in a healthy foot and after section and repair with augmentation and transfer of the flexor digitorum longus (FDL). It also compared the two repair techniques, both individually with augmentation and with transfer.

Study rationaleThis study aimed to evaluate the biomechanical impact of the plantar calcaneonavicular ligament, with particular emphasis on its contribution to the stability of the talonavicular joint and the implications of the repair techniques used to achieve results biomechanically comparable to those of an intact ligament. This idea aligns with the concerns of numerous previous authors who have suggested that calcaneonavicular ligament reconstruction would enhance the correction achieved by bone realignment procedures.4

Based on these considerations, it was hypothesised that studying the biomechanical behaviour of the healthy foot after sectioning and subsequent reconstruction of the calcaneonavicular ligament would allow for the assessment of its role in joint stability and the effectiveness of the surgical techniques applied. The objectives of this study were to describe the importance of the calcaneonavicular ligament in the stability of the tibiotalar and subtalar joints, as well as to detail the surgical technique of ligament augmentation and tendon transfer of the calcaneonavicular ligament as a functional reconstruction strategy.

Material and methodsA comparative experimental study was conducted on cadavers at time zero, evaluating two surgical techniques for the treatment of calcaneonavicular patellofemoral pain syndrome (CAPFSPS): calcaneonavicular ligament repair and augmentation, and calcaneonavicular ligament transfer.

Sample descriptionThe study was conducted using 25 anatomical specimens of frozen ankles obtained from the Cadaver Donation Centre of the Complutense University of Madrid. All specimens were obtained according to the centre's established protocol.

Exclusion criteria were applied for specimen selection, including a history of previous surgeries, rheumatic or tumourous diseases, joint stiffness, or significant deformities that could interfere with the proper execution of the study. Ultimately, 25 ankles were included, 12 from the right side and 13 from the left, distributed between 13 female and 12 male specimens. The sample had a mean age of 74.08 years, with a median of 73 years, and the age range of participants was between 52 and 95 years.

For the sample size estimate, a 95% confidence level and a maximum estimation error of .2 were established. Using the formula for infinite populations, n=(Z_α^2 PQ)/e^2, we obtained a required sample size of 25 cadaveric specimens.

The study was based on analysing the stability of the talonavicular joint after the two previously mentioned surgical techniques, which ultimately aim to restore the function of the calcaneonavicular ligament. For this analysis, four exploratory manoeuvres were performed, including abduction/external rotation, pronation, plantar flexion, and axial loading.

These manoeuvres were performed in the four consecutive phases of the study: calcaneonavicular ligament integrity (1); section of the calcaneonavicular ligament (2); repair and augmentation of the calcaneonavicular ligament (3); and FDL transfer (4). Comparing the effectiveness of these last two techniques, which were performed sequentially.

Study preparationThe cadaveric specimen was initially stabilised using a clamp anchored to the distal tibia, allowing for individualised movement of the foot and ankle. Two Kirschner wires were inserted into the body of the navicular bone to create a rigid connection and measure the range of motion in all three spatial axes. All specimens were dissected and analysed by the same examiner to minimise intra-observer variability.

A neutral starting point was initially established for the arthrometer, after which a reference value was recorded without applying any force. Once the values after movement were obtained, the difference between the two data points was calculated to obtain the final displacement angles. Each measurement was taken three times, and a final average of the three values was calculated to achieve greater accuracy. All manoeuvres were performed by the same experienced operator to minimise variability. However, due to the potential variation in applied force in studies involving manual assessment, an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated, demonstrating high reproducibility between measurements and lending robustness and consistency to the data obtained.

Four manual manoeuvres were performed to determine talonavicular joint stability: abduction and external rotation (1); pronation and eversion (2); collapse and plantar flexion (3); and axial loading (4), which was performed with an external support that forced a plantigrade position.

The prototype quantified rotations in the spatial planes (axial, coronal, and sagittal) after these manoeuvres had been performed.

In the axial plane, external rotation movements were defined with positive values, while internal rotation movements were represented with negative values. In the coronal plane, supination/inversion movements were assigned positive values, and pronation/eversion movements, negative values. Finally, in the sagittal plane, positive values were assigned for plantar flexion movements and negative values for dorsiflexion movements.

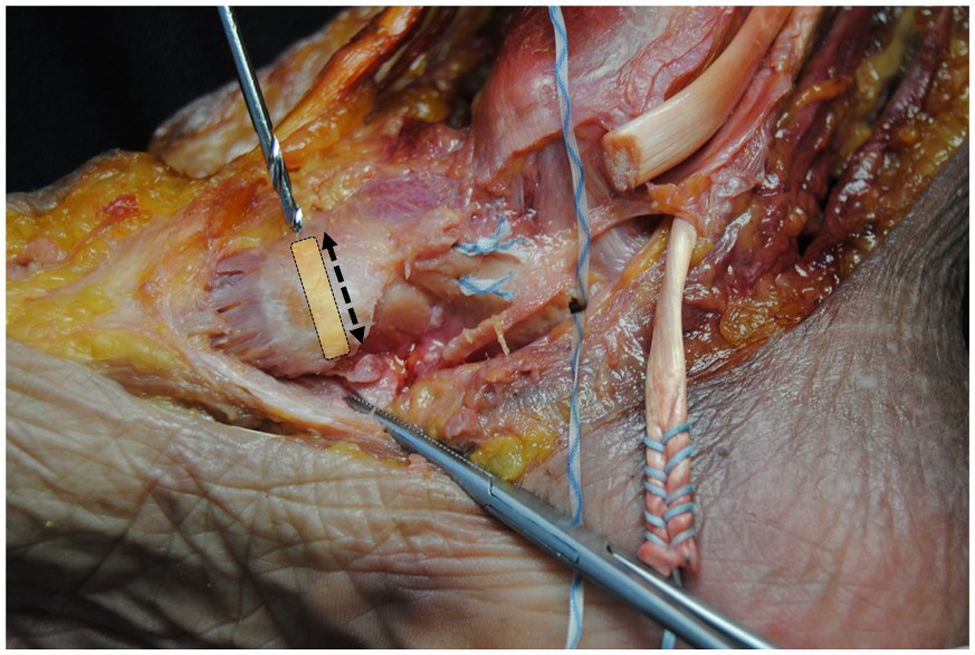

Study protocolFirst, an approach was made to the medial column, identifying the calcaneonavicular ligament, as well as the flexor digitorum longus (FDL), flexor hallucis longus, and tibialis posterior muscles. Calcaneonavicular ligament sectioning was performed, simulating the most frequent injury found in PCFD. For this, access was gained via a medial approach, and the hammock ligament structure was identified and carefully sectioned with a scalpel. The section focused on the superomedial fascicle, primarily responsible for stabilising the medial arch and commonly affected in this condition. Subsequently, the ligament was repaired using simple interrupted sutures with high-strength FiberWire® (Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA) and reinforced with FiberTape® (Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA). We inserted a 1.35mm Kirschner wire at the level of the sustentaculum tali with a plantar angulation of 15° and slightly posterior to avoid violating the subtalar joint. Drilling was performed with a 2.7mm drill bit, followed by a 3.5mm SwiveLock® implant (Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA) loaded with FiberTape®. Next, we created a complete tunnel in the navicular tubercle by inserting the FiberTape® from plantar to dorsal and from dorsal to plantar, securing it with a 5.5mm biotenodesis screw (Fig. 1).

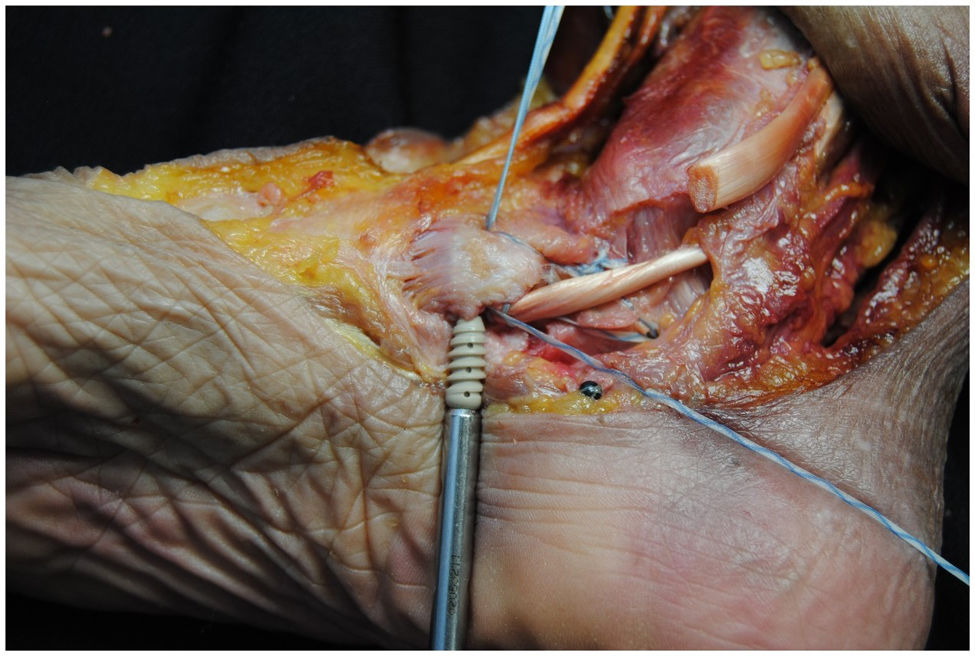

For the second technique, we added the FDL transfer, which was sectioned as close as possible to the Master Know of Henry. The FDL was prepared with a high-strength FiberLoop® suture (Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA), and the tendon was inserted into the previously created tunnel of the navicular tubercle, from plantar to dorsal (Fig. 2).

Description of the measuring instrumentRegarding the measuring system, an arthrometer designed by the Department of Mechanical Engineering of the Instituto Superior Técnico in Lisbon was used to determine the angular stability of the talonavicular joint. It consisted of an MPU-6050 GY-521, a 6-degree-of-freedom inertial measurement unit (IMU) with a 3-axis accelerometer and a 3-axis gyroscope to measure angles in real time. These measurements were processed using an algorithm and specialised software for data fusion.

The IMU sensor was controlled by an Arduino Mega 2560 board, which was used as a microcontroller. System calibration ensured that the gyroscopes accurately measured the rotation angles between the initial and final positions after each step of the test protocol.

Statistical analysisGiven the small sample size, a normal distribution could not be assumed for the data; therefore, the Wilcoxon test was used as a non-parametric analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using R software version 4.3.1. The stability of the healthy calcaneonavicular ligament was compared to that of the injured ligament after the two reconstruction techniques. A p value ≤.05 was considered statistically significant.

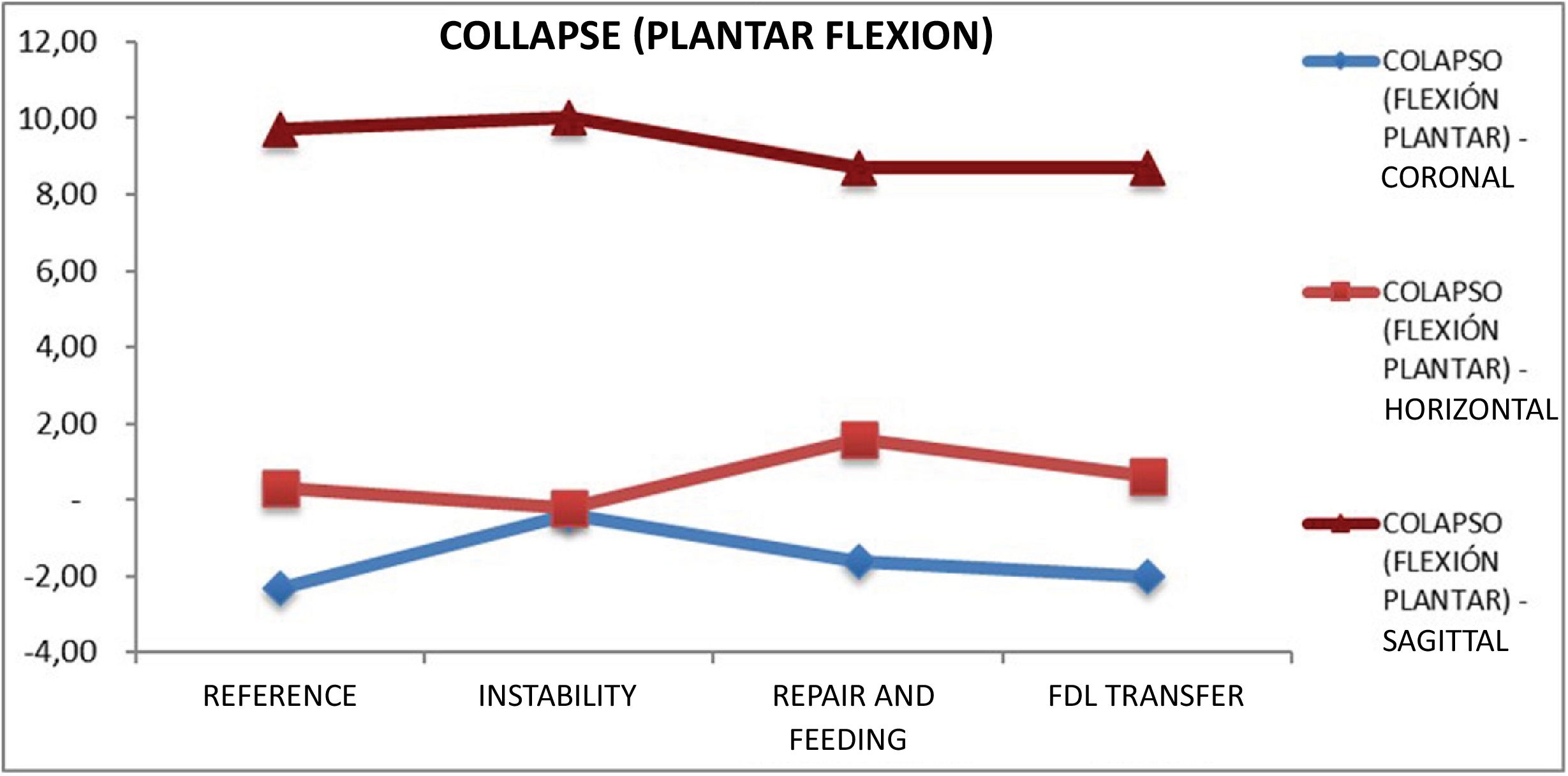

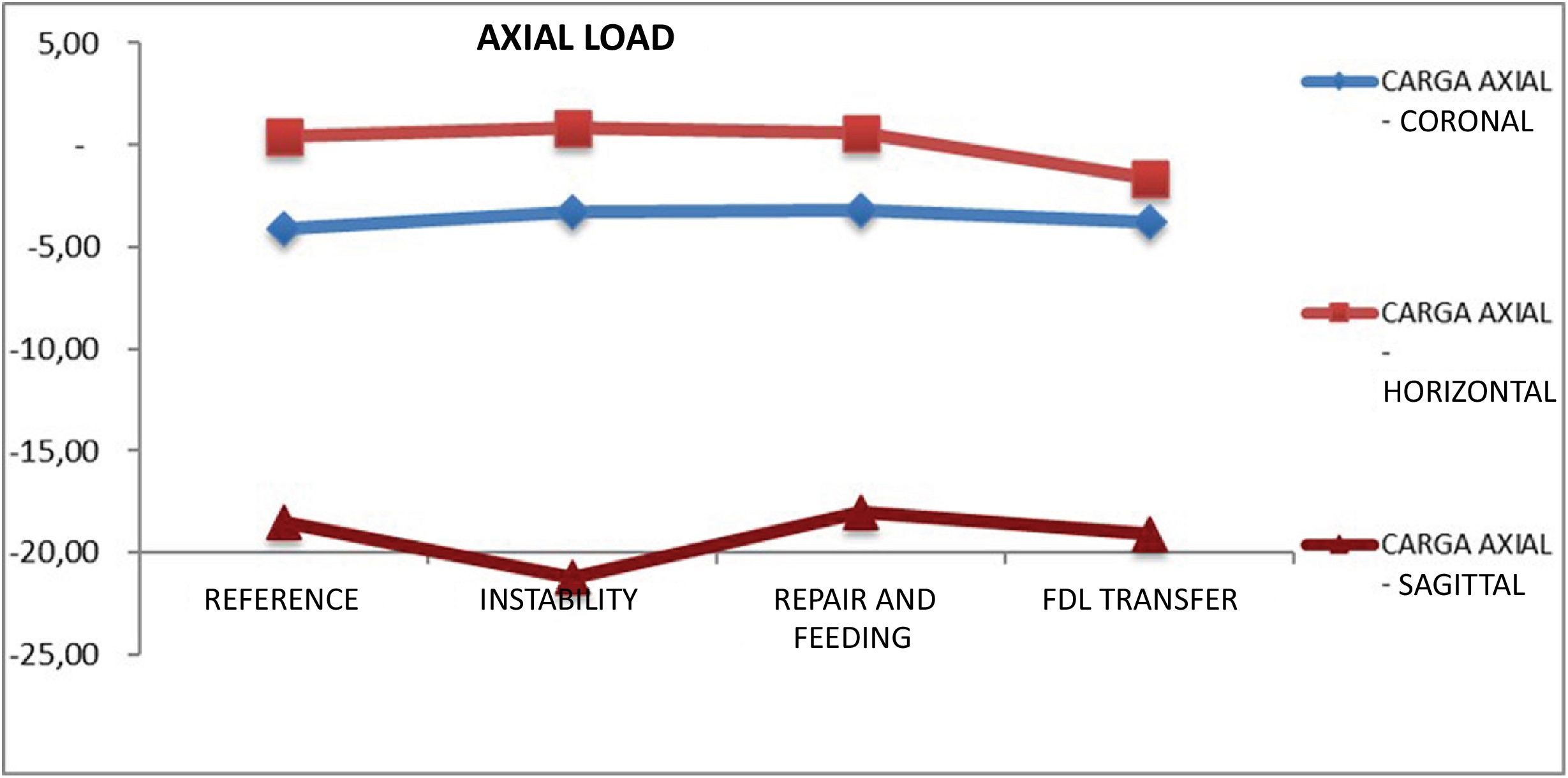

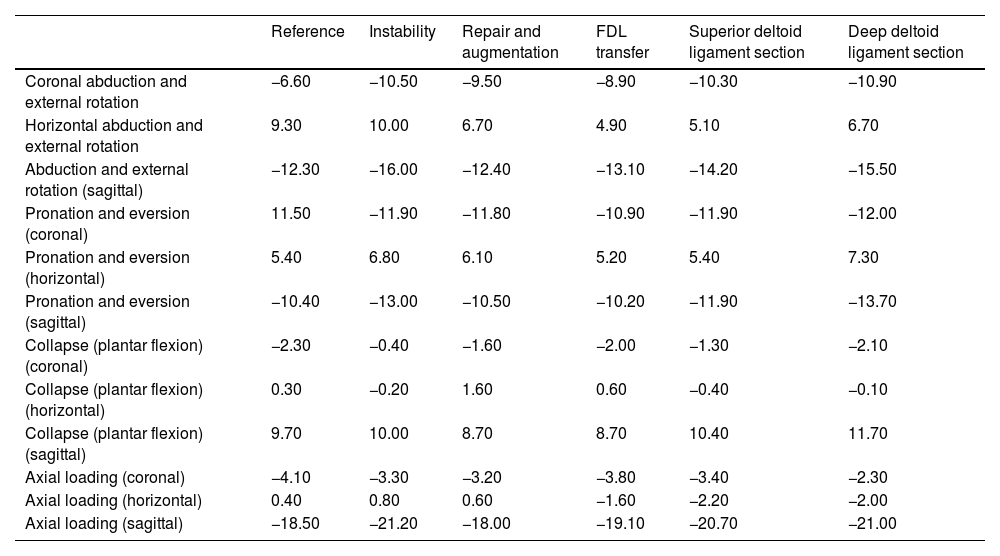

ResultsFirst, a descriptive data analysis was performed, collecting the means with their standard deviations and the medians with their interquartile ranges for each movement in each of the three planes after the exploratory manoeuvres (abduction and external rotation, pronation and eversion, collapse and plantar flexion, axial loading) in the different states already described (intact, ligament section, repair and augmentation, and transfer of the flexor digitorum longus). All of this is summarised in Table 1.

The descriptive analysis of the angular displacement of the talonavicular joint, obtained through different examination manoeuvres in the three spatial planes.

| Reference | Instability | Repair and augmentation | FDL transfer | Superior deltoid ligament section | Deep deltoid ligament section | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coronal abduction and external rotation | −6.60 | −10.50 | −9.50 | −8.90 | −10.30 | −10.90 |

| Horizontal abduction and external rotation | 9.30 | 10.00 | 6.70 | 4.90 | 5.10 | 6.70 |

| Abduction and external rotation (sagittal) | −12.30 | −16.00 | −12.40 | −13.10 | −14.20 | −15.50 |

| Pronation and eversion (coronal) | 11.50 | −11.90 | −11.80 | −10.90 | −11.90 | −12.00 |

| Pronation and eversion (horizontal) | 5.40 | 6.80 | 6.10 | 5.20 | 5.40 | 7.30 |

| Pronation and eversion (sagittal) | −10.40 | −13.00 | −10.50 | −10.20 | −11.90 | −13.70 |

| Collapse (plantar flexion) (coronal) | −2.30 | −0.40 | −1.60 | −2.00 | −1.30 | −2.10 |

| Collapse (plantar flexion) (horizontal) | 0.30 | −0.20 | 1.60 | 0.60 | −0.40 | −0.10 |

| Collapse (plantar flexion) (sagittal) | 9.70 | 10.00 | 8.70 | 8.70 | 10.40 | 11.70 |

| Axial loading (coronal) | −4.10 | −3.30 | −3.20 | −3.80 | −3.40 | −2.30 |

| Axial loading (horizontal) | 0.40 | 0.80 | 0.60 | −1.60 | −2.20 | −2.00 |

| Axial loading (sagittal) | −18.50 | −21.20 | −18.00 | −19.10 | −20.70 | −21.00 |

The mean and standard deviation were used as analytical methods for data collection.

FDL: flexor digitorum longus.

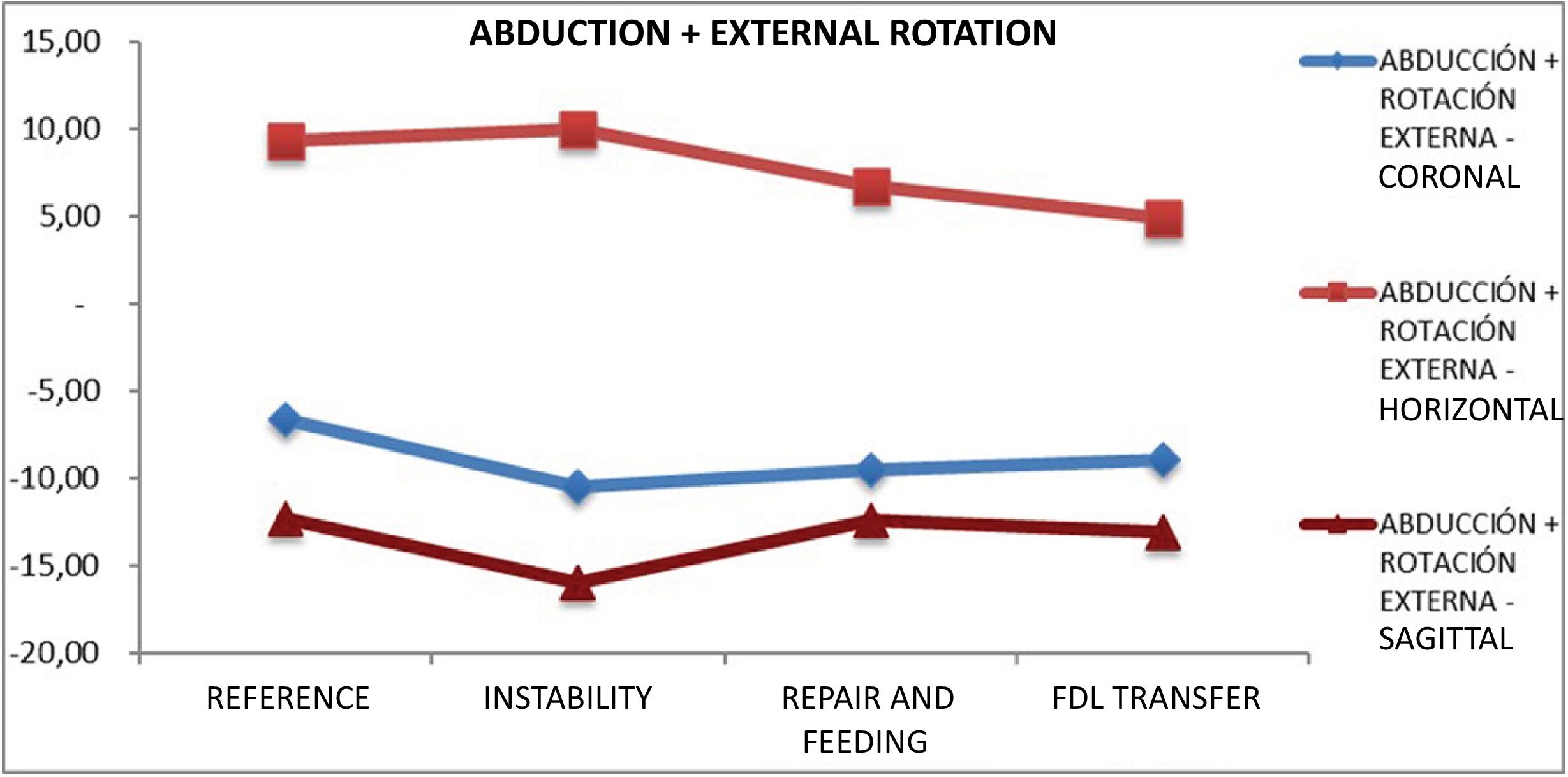

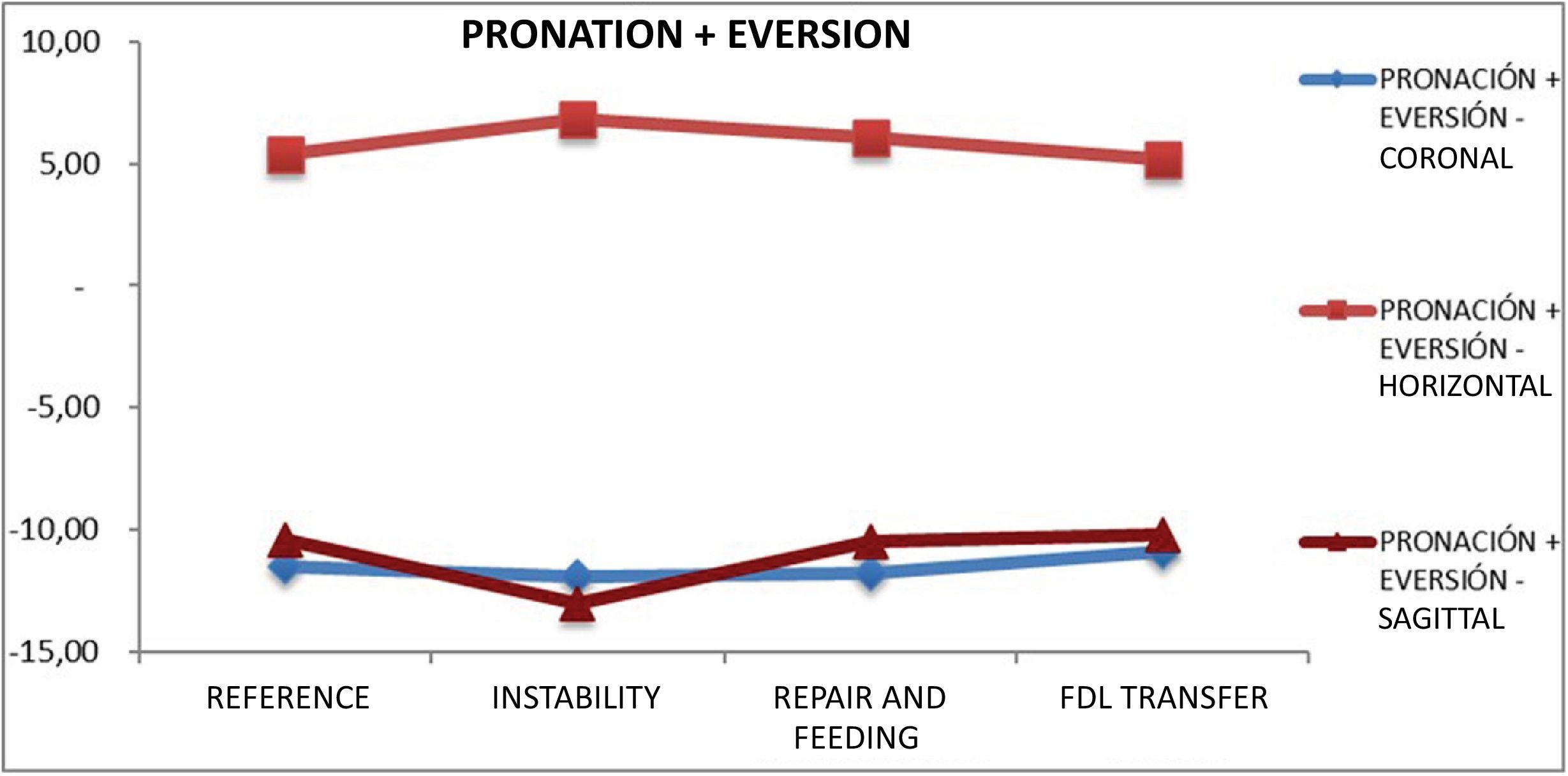

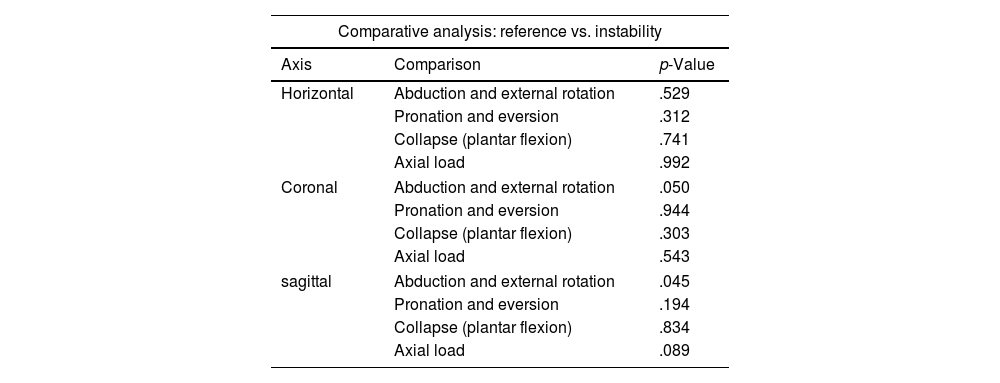

Figs. 3–6 show the evolution of the mean for each of the studied states after each explored movement. It can be observed that we start from a reference value with the ligament intact, and after its section, instability develops with marked increases in mobility in all movements. The comparative analysis of biomechanical behaviour between the baseline and unstable states revealed statistically significant differences in abduction and external rotation manoeuvres in the coronal and sagittal planes (p=.050 and p=.045, respectively) (Table 2).

The comparative analysis of the calcaneonavicular ligament.

| Comparative analysis: reference vs. instability | ||

|---|---|---|

| Axis | Comparison | p-Value |

| Horizontal | Abduction and external rotation | .529 |

| Pronation and eversion | .312 | |

| Collapse (plantar flexion) | .741 | |

| Axial load | .992 | |

| Coronal | Abduction and external rotation | .050 |

| Pronation and eversion | .944 | |

| Collapse (plantar flexion) | .303 | |

| Axial load | .543 | |

| sagittal | Abduction and external rotation | .045 |

| Pronation and eversion | .194 | |

| Collapse (plantar flexion) | .834 | |

| Axial load | .089 | |

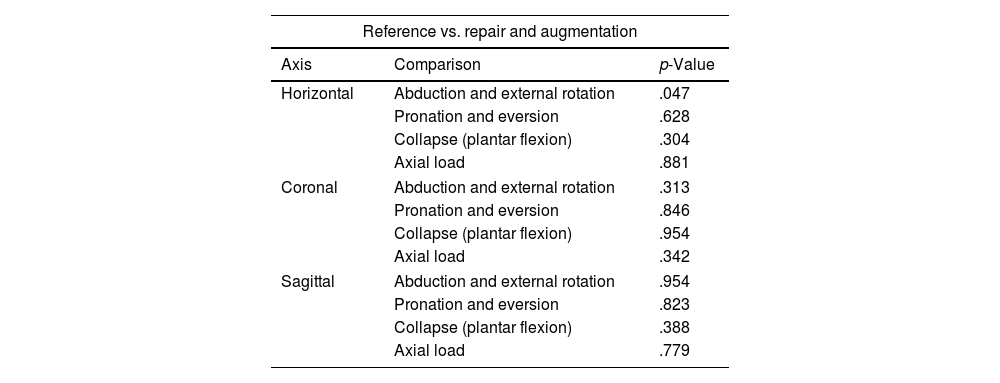

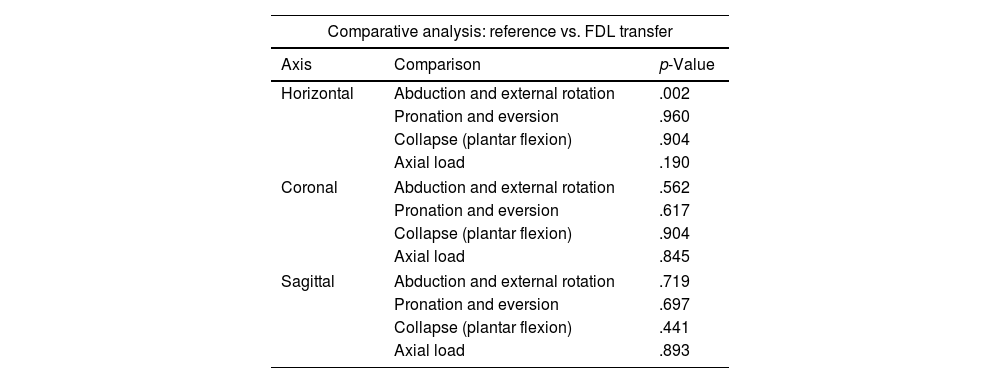

After repair and augmentation, an improvement in these values was observed. Subsequently, with the transfer of the FDL, this improvement intensified, achieving stability superior to that of the baseline foot at all points. Comparing the baseline state with the repair and augmentation, we observed statistically significant differences for abduction and external rotation manoeuvres in the horizontal plane (p=.047) (Table 3). The result was also significant when comparing the baseline values with the RCM transfer (p=.002) (Table 4).

The comparative analysis of the calcaneonavicular ligament.

| Reference vs. repair and augmentation | ||

|---|---|---|

| Axis | Comparison | p-Value |

| Horizontal | Abduction and external rotation | .047 |

| Pronation and eversion | .628 | |

| Collapse (plantar flexion) | .304 | |

| Axial load | .881 | |

| Coronal | Abduction and external rotation | .313 |

| Pronation and eversion | .846 | |

| Collapse (plantar flexion) | .954 | |

| Axial load | .342 | |

| Sagittal | Abduction and external rotation | .954 |

| Pronation and eversion | .823 | |

| Collapse (plantar flexion) | .388 | |

| Axial load | .779 | |

The comparative analysis of the calcaneonavicular ligament.

| Comparative analysis: reference vs. FDL transfer | ||

|---|---|---|

| Axis | Comparison | p-Value |

| Horizontal | Abduction and external rotation | .002 |

| Pronation and eversion | .960 | |

| Collapse (plantar flexion) | .904 | |

| Axial load | .190 | |

| Coronal | Abduction and external rotation | .562 |

| Pronation and eversion | .617 | |

| Collapse (plantar flexion) | .904 | |

| Axial load | .845 | |

| Sagittal | Abduction and external rotation | .719 |

| Pronation and eversion | .697 | |

| Collapse (plantar flexion) | .441 | |

| Axial load | .893 | |

FDL: flexor digitorum longus.

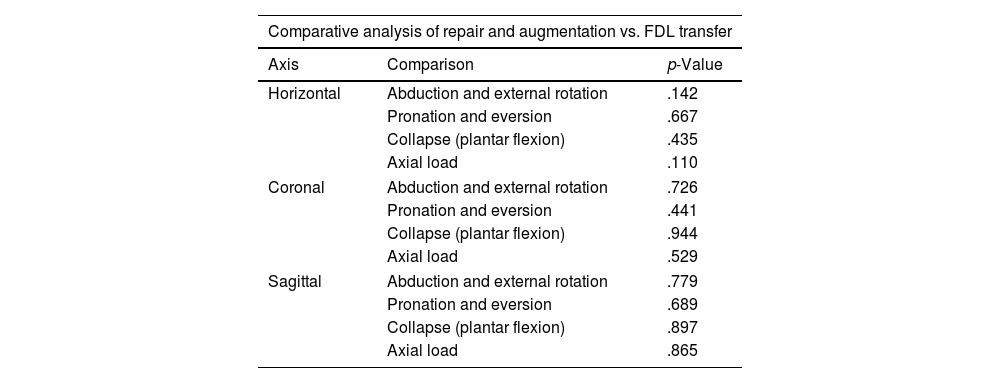

Comparing the repair and augmentation technique with the transfer technique, no statistically significant differences were found (Table 5).

The comparative analysis of the calcaneonavicular ligament.

| Comparative analysis of repair and augmentation vs. FDL transfer | ||

|---|---|---|

| Axis | Comparison | p-Value |

| Horizontal | Abduction and external rotation | .142 |

| Pronation and eversion | .667 | |

| Collapse (plantar flexion) | .435 | |

| Axial load | .110 | |

| Coronal | Abduction and external rotation | .726 |

| Pronation and eversion | .441 | |

| Collapse (plantar flexion) | .944 | |

| Axial load | .529 | |

| Sagittal | Abduction and external rotation | .779 |

| Pronation and eversion | .689 | |

| Collapse (plantar flexion) | .897 | |

| Axial load | .865 | |

FDL: flexor digitorum longus.

After conducting the study and exhaustive data analysis, it was possible to verify the importance of the calcaneonavicular ligament in midfoot stabilisation, especially in the coronal and sagittal planes. Previous cadaveric studies confirmed its primary role in the static restriction of peritalar subluxation of the talus head, preventing the displacement of the load from the hindfoot to the lateral column.12,15 The work of Jennings et al. and Hintermann et al. also demonstrated the importance of the calcaneonavicular ligament in maintaining sagittal alignment of the hindfoot and in reducing pronation in this region. In our study, a tendency toward instability in these parameters after ligament section was also demonstrated, although it did not reach statistical significance.16,17

Currently, many researchers advocate for the use of calcaneonavicular ligament reconstruction in the context of severe flatfoot deformity to avoid more aggressive techniques such as arthrodesis. 5 Multiple repair techniques using allografts and autografts have been implemented for this purpose, ranging from transfers of the peroneus longus, tibialis anterior, and flexor hallucis longus muscles to the use of bone block grafts of the deltoid ligament.5,18–21 All of these techniques were associated with significant morbidity and loss of strength, leading to the development of new augmentation systems as an alternative.

These repair systems were described as a safe and effective alternative, demonstrating improved strength compared to standard ligament repair. Biomechanical cadaver studies, such as that by Acevedo and Vora, developed repair techniques similar to the one described in our study, achieving good results and evaluating the use of these techniques in conjunction with deltoid ligament transfer and medialising osteotomies.22–24

Palmanovich et al. reported improvements in the AOFAS score from 55.8 before surgery to 97.6 one-year post-surgery using FiberTape® (Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA).25 Several authors have established that isolated ligament repairs and transfers often fail in isolation, making combinations of various repair techniques an attractive option for surgical stabilisation.5,26,27 This led to the idea of adding the standard FDL transfer to augmentation.

The results in the specimens in our study concluded that both techniques recreated the normal anatomical constraints of the ligament. It is of note that both techniques showed remarkably similar results, suggesting that they could be equally effective in achieving a degree of stabilisation similar to that of an intact ligament.

Although larger studies with long-term follow-up are still required, calcaneonavicular ligament reconstruction has been extensively investigated as a potentially effective procedure for talonavicular joint realignment.28–30 Evaluating the efficacy of repair techniques remains challenging due to the diversity of surgical approaches and the frequent use of concomitant procedures in flatfoot reconstruction. However, the findings of our study suggest that repair could significantly restore the biomechanical characteristics of the midfoot arch. While conclusive evidence demonstrating the superiority of one technique over another is still lacking, these results align with previous studies and reinforce the path toward more personalised and effective surgical strategies. Future research should be based on sound methodological design and robust biomechanical evidence to optimise surgical interventions in the treatment of flatfoot.

Limitations and strengthsSince this study was conducted on cadaveric specimens, it is important to acknowledge the inherent limitations of this experimental model, which restrict the extrapolation of the findings to the dynamic conditions of living subjects. Although tendons in inert specimens lose their dynamic function, their inclusion allows for the evaluation of the structural and passive contribution of interventions in ligament reconstruction. In clinical practice, various surgical techniques employ passive reinforcements to stabilise the joint, justifying their use in the cadaveric model. The lack of body weight in the specimens limits the exact replication of physiological loads, but the cadaveric model allows for the precise study of the structural mechanics of the interventions. It should also be noted that the sectioning of the calcaneonavicular ligament was performed by direct anatomical identification, without histological confirmation, which may introduce some variability in the exact delimitation of the affected fascicles, although every effort was made to reproduce the most common injury pattern observed in clinical practice.

It was to our advantage that the biomechanical and anatomical properties of the fresh-frozen model used in this study closely resembled those of an ankle in a living subject. Similarly, the examination manoeuvres performed on a cadaver faithfully reproduce those carried out in a clinical setting. This enabled us to study the actual anatomy of the ligament, including its relationship to nearby structures and its biomechanical interaction with them. This three-dimensional analysis, whose reproducibility is limited by other methods, provided a solid starting point for comparison with studies based on histological parameters and imaging tests.

This cadaveric study tested the intrinsic stability of both repairs and did consider the repair and fibrosis processes that occur over time in the ankle of a patient treated with this technique.

ConclusionsCalcaneonavicular ligament sectioning caused instability in the coronal and sagittal planes during abduction and external rotation movements. Surgical repair techniques involving augmentation and FDL transfer restored joint stability, demonstrating even greater strength than the intact ligament. Statistical analyses showed a significant improvement in the stability of the medial plantar arch with both techniques (abduction and external rotation: repair, p=.047; FDL transfer, p=.002), with no significant differences between them. This study reinforces the importance of the calcaneonavicular ligament in midfoot biomechanics and validates the effectiveness of these surgical techniques for its reconstruction.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence III.

FundingThis study was enabled thanks to the financial support received through the SECOT Foundation’s 2022 call for proposals for “Research Initiation Projects.”

Ethical considerationsThis research was reviewed by the Bioethics Committee of the University Hospital of Móstoles and approved on March 28, 2023. No relevant ethical issues were identified in this manuscript.

Conflict of interestsThe author, J. Vilá y Rico, is an international consultant for Arthrex.

We would like to express our gratitude to the staff of the Department of Anatomy and Embryology at the Complutense University of Madrid, and also to the technical team in the dissection room, for their collaboration in carrying out this research. We also thank Arthrex Spain for the generous provision of the materials necessary for this study.