Experimental post-traumatic arthrofibrosis studies have been conducted using mostly rabbit models. However, there is great interest in developing and validating models in smaller animals, which would allow for more cost-effective research. The aim is to validate a model in rats recently described by Owen et al.

Materials and methodsTwenty 14-weeks old Sprague-Dawley female rats were used in the study: 10 rats were used to assess biomechanical contracture, as passive extension angle at different torques (PEA-2, PEA-4, PEA-8) and at capsule disruption, and 10 rats to assess histological fibrosis (area and thickness of posterior capsule). Left knee acted as control. Index surgery was performed on the right knee (operated knee) as described by Owen at al.: intra-articular injury, disruption of posterior capsule, and immobilization with a percutaneous suture in flexion. After a 4-week immobilization period, the suture was removed, followed by another 4-week remobilization period and euthanasia.

ResultsOperated knees showed lower PEA-4 (−40.6°; p=.011), PEA-8 (−45.6°; p=.044) and PEA at capsule disruption (−66.5°; p=.043) than the control knees. Mean PEA-2, PEA-4 and PEA-8 from our sample were similar to those reported by Owen et al. Operated knees showed a larger posterior capsule area (1.82mm2; p=.033) and thickness (.31mm; p=.043) than the control knees.

ConclusionsThe post-traumatic arthrofibrosis model described by Owen et al. has the capacity to induce biomechanical contracture and histological fibrosis. Our biomechanical results are comparable to those of Owen, supporting the model's reproducibility.

La investigación preclínica sobre la artrofibrosis postraumática se ha centrado principalmente en modelos experimentales de conejo. No obstante, existe un creciente interés por desarrollar y validar modelos en animales de menor tamaño, lo que permitiría una investigación más coste-efectiva. El objetivo de este estudio es validar el modelo en rata descrito recientemente por Owen et al.

Material y métodosSe utilizaron 20 ratas hembra Sprague Dawley de 14 semanas de edad: 10 se emplearon para el análisis de la rigidez biomecánica, mediante la medición del ángulo de extensión pasiva (passive extension angle [PEA]) a diferentes pares de torsión (PEA-2, PEA-4, PEA-8) y en el momento de rotura capsular, y 10 se emplearon para el análisis de la fibrosis histológica, mediante la medición del área y el grosor de la cápsula posterior. La rodilla izquierda se utilizó como control. La cirugía inicial se realizó sobre la rodilla derecha (rodilla operada) según la técnica descrita por Owen et al.: lesión intraarticular, rotura de la cápsula posterior e inmovilización en flexión mediante una sutura percutánea. Tras 4 semanas de inmovilización, se retiró la sutura y se permitió la libre movilidad durante otras 4 semanas antes del sacrificio.

ResultadosLas rodillas operadas presentaron un menor PEA-4 (−40,6°; p=0,011), PEA-8 (−45,6°; p=0,044) y PEA en la rotura capsular (−66,5°; p=0,043 en comparación con las rodillas control. Los valores medios obtenidos en nuestra serie para PEA-2, PEA-4 y PEA-8 fueron comparables a los de Owen et al. Las rodillas operadas presentaron una mayor área (1,82mm2; p=0,033) y grosor (0,31mm; p=0,043) de la cápsula posterior en comparación con las rodillas control.

ConclusionesSegún nuestros resultados, el modelo de artrofibrosis postraumática descrito por Owen et al. es capaz de inducir rigidez biomecánica y fibrosis histológica. Nuestros resultados biomecánicos son comparables a los de Owen, lo que confirma la reproducibilidad del modelo.

Joint stiffness following traumatic or surgical injury (post-traumatic arthrofibrosis) is primarily caused by excessive fibrosis of the joint capsule. This stiffness is particularly relevant in joints with high congruence, such as the knee or elbow, following trauma or invasive surgery that alters joint structures.1–4 Currently, the only therapeutic strategies for treating stiffness are physiotherapy or surgical release.5–10 Unfortunately, aside from early mobilisation, there are no effective preventive therapies that reduce capsular fibrosis after traumatic injury or reconstructive surgery.11–16 The reasons why some patients develop excessive fibrosis after trauma or surgery remain unknown. However, in recent years, advances have been made in understanding the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved. It is known that movement limitation originates in the joint capsule rather than the musculature.17–19 Furthermore, an increase in fibroblast cells, known as myofibroblasts, has been observed in the joint capsule during the first two weeks following trauma. This suggests that these cells are primarily responsible for the development of arthrofibrosis.20–22

Most experimental studies have been conducted using rabbit models. This model has proven to be valid and reproducible for biomechanical and histological evaluations.17,23,24 However, there is great interest in developing and validating models in smaller animals, which would make research more economical.25,26 In particular, a reproducible model of joint stiffness in rats would significantly reduce costs and facilitate the study of a wide variety of therapeutic agents, given the extensive knowledge available on the pharmacokinetics of numerous drugs in this species.

Some authors have attempted to use rat models, although in certain cases immobilisation alone has been used without inducing joint injury, periods of remobilisation have been omitted, or the articular cartilage or muscle has been injured.27–33 Li et al.34 adapted the rabbit model described by Hildebrand for use with rats, using polypropylene sutures; however, they did not demonstrate that stiffness persisted following the period where motion was unlimited. Baranowski et al.19 developed a rat knee model that included a capsular injury and an extracartilaginous defect, with immobilisation using a transosseous Kirschner wire for four weeks and subsequent remobilisation. However, no histological or molecular evaluations were performed to confirm capsular fibrosis, and the use of transosseous needles carried a risk of migration or iatrogenic fracture. Furthermore, studies using this model to test pharmacological treatments failed to demonstrate differences from the control limb, possibly due to the model's lack of sensitivity.35–37 Therefore, Owen et al.25 developed a new rat model, integrating knowledge from previous studies in rabbits. The aim was to enable larger-scale, more cost-effective research into the treatment of post-traumatic arthrofibrosis. This model incorporates severe joint injury, periods of immobilisation and remobilisation, biomechanical evaluation under standardised torque pairs, and histological assessment using quantitative measures.

The aim of this study is to validate the post-traumatic arthrofibrosis model described by Owen et al., demonstrating its ability to induce biomechanical stiffness and histological capsular fibrosis, as well as its reproducibility.

Material and methodsAnimals and housing conditionsThis study was approved by our institution's animal experimentation committee (PROEX 227.6/23; 29/09/2023). All animals in the study were purchased from Janvier Laboratories, Inc. (Saint-Berthevin, France) and remained in quarantine for one week after arrival before being transferred to the experimentation room. Rats were housed in groups (n=4 per cage), with ad libitum access to standard feed and filtered tap water. Environmental conditions were kept constant (temperature 21±2°C and humidity 45±10%). The photoperiod was set to provide 12h of light per day, and environmental enrichment elements were provided.

Study designProspective experimental study.

Twenty 14-week-old female Sprague-Dawley rats (Rattus norvegicus domestica), weighing an average of 305.1g (SD: 31.5), were used. Using a single sex reduced inter-individual variability. Ten rats were assigned to the biomechanical study and 10 to the histological study. In each animal, the experimental intervention was performed on the right knee (operated knee), while the left knee served as an internal control (control knee).

ProcedureInitial surgeryAn identical surgical procedure was performed on the right knee of each rat, following the protocol described by Owen et al.,25 with the exception of the percutaneous immobilisation system, which is explained below. All procedures were performed under general anaesthesia with inhaled sevoflurane (8% for induction and 3.5–4% for maintenance in 1L of oxygen) via a nasal mask. Antibiotic prophylaxis was administered with cefazolin (30mg/kg), postoperative analgesia with buprenorphine (.1mg/kg), and subcutaneous local anaesthesia in the incision area with bupivacaine (2ml of a 2g/100ml solution) prior to surgical incision. The knees were prepared with povidone-iodine solution and kept sterile. A medial skin incision was made over the knee and a lateral parapatellar arthrotomy was performed. The cruciate ligaments were sectioned and extracartilaginous cortical defects were created in the medial and lateral femoral condyles using an 18G needle. Care was taken to preserve the collateral ligaments. The knee was then hyperextended to 45° to cause rupture of the posterior capsule. The knee was immobilised in full flexion using the percutaneous method described by Dagneaux et al.38 A 22-gauge intramuscular needle was used to pass a non-absorbable suture (2-0 Prolene; Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, USA) percutaneously. The needle was inserted through the anterior aspect of the femur at the level of the mid-diaphysis, and directed laterally towards the tibia, and it emerged through the anterior surface of the tibia. The suture was passed in a retrograde direction until it emerged on the medial aspect of the femur. The suture was tied around the anterior tibia next to the bone. The arthrotomy and skin were closed with absorbable sutures. A fluoroscopic image was obtained to confirm correct immobilisation and rule out iatrogenic fracture. The animals received 5ml of subcutaneous saline and were transferred to a warm recovery cage.

Immobilisation periodFollowing the initial surgery, the rats were kept in free activity cages for a four-week immobilisation period. Oral buprenorphine (.4mg/kg), dissolved in chocolate spread, was administered for the first few days post-operatively.

Removal of the immobilisation suture and remobilisation periodAt the end of the 4-week immobilisation period, a second procedure was performed to remove the suture. The preparation and anaesthesia were identical to those used in the initial surgery. A fluoroscopic image was obtained to verify immobilisation in full flexion. Through a small skin incision, the knot was located on the medial side of the femur, the suture was cut and removed. The rats then remained with free cage activity for another 4 weeks (remobilisation period).

Euthanasia and removal of the kneesAfter the remobilisation period, the animals were euthanised by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (3ml of a 1:10 solution) and both knees (operated and control) were removed by disarticulation of the hip and ankle. This left the femur and tibia joined by all soft tissues except the skin.

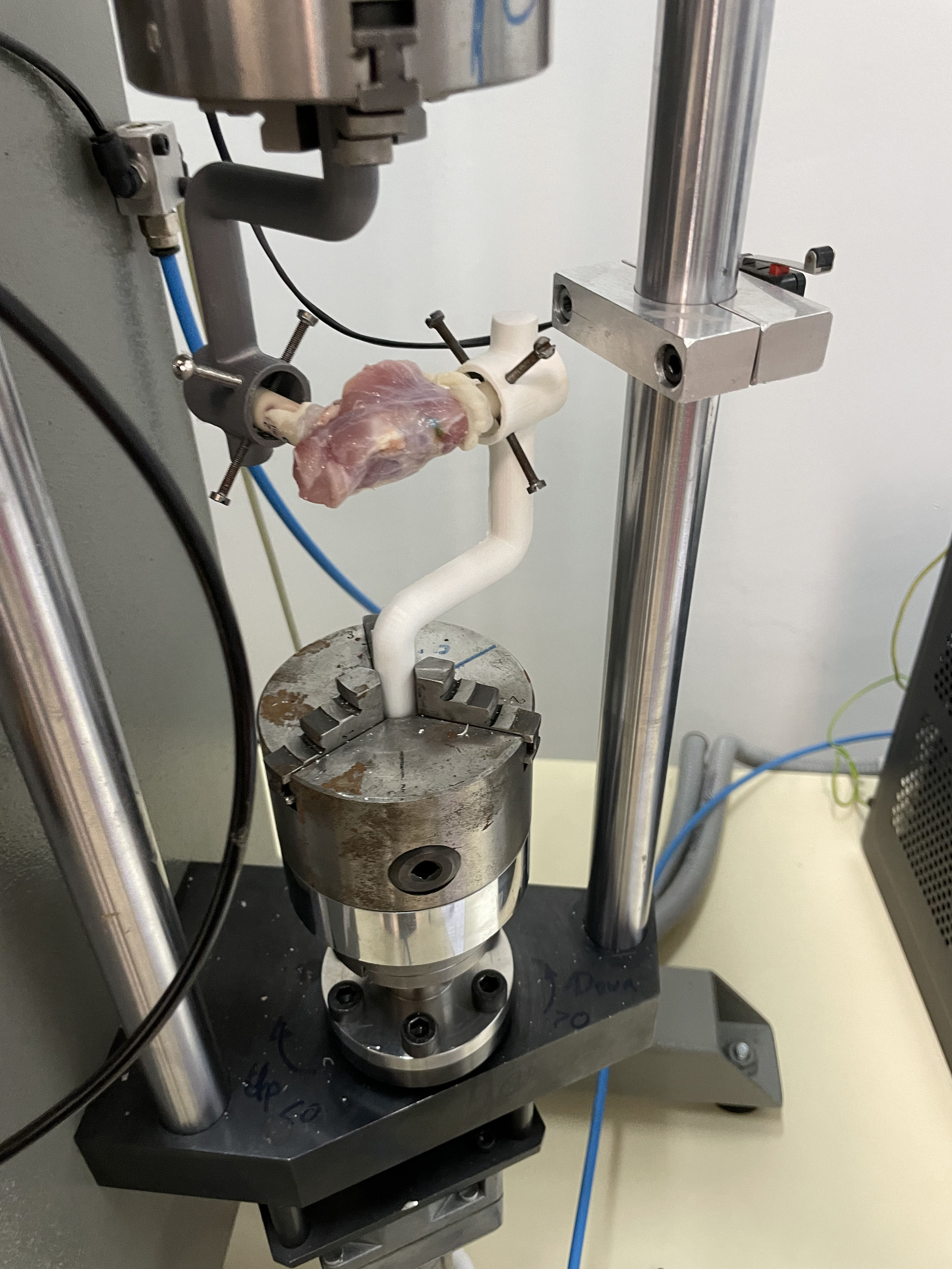

Processing and biomechanical analysisThe proximal ends of the femur and distal ends of the tibia were prepared to expose the cortical bone, while preserving the posterior capsule and periarticular tissues up to 1cm proximal and distal to the joint. The samples were transported to the biomechanics laboratory in physiological saline and evaluated within a maximum of 6h. The bone ends were fixed with polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA; Stryker, Mahwah, NJ, USA) cement in 5ml syringes. The knee was attached to a 3D-printed polylactic acid (PLA) support, which was connected to a 10Nm dynamic load cell (Servosis Testing Machines, Madrid, Spain) to record the torque applied at a constant speed of 1°/s until failure (Fig. 1). Particular care was taken to align the axis of rotation of the knee with that of the machine. The passive extension angle (PEA) was recorded for each knee. The biomechanical test was performed until complete rupture of the capsule, generating a PEA (degrees) – torque (Nm) curve. The digital files for each curve were blinded for the principal investigators. PEA values were determined from the curves at 2N-cm (PEA-2), 4N-cm (PEA-4), and 8N-cm (PEA-8), as well as the PEA and torque at the point of capsular disruption. This was defined as the first peak of the curve with a sharp drop in torsional resistance.39,40

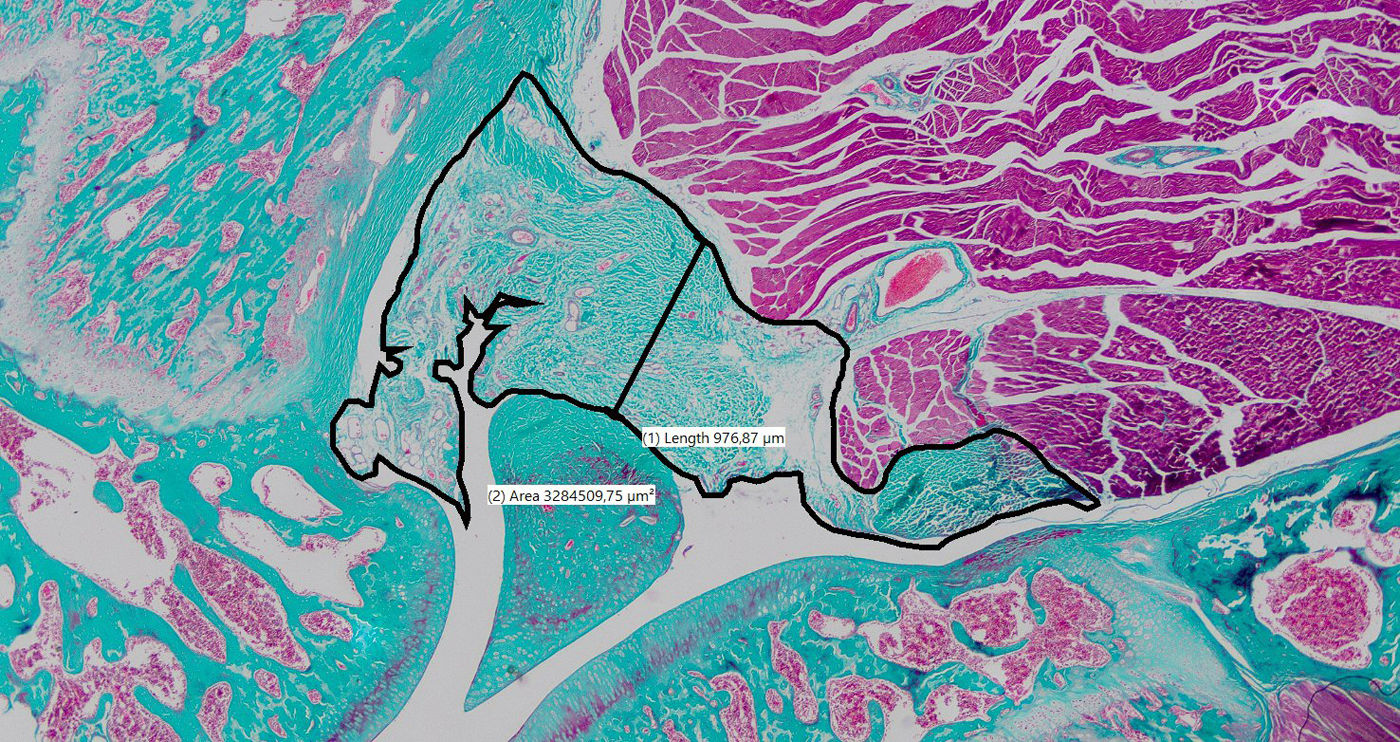

Histological processing and analysisThe knees were fixed immediately in 10% buffered formalin and sent to our institution's pathology laboratory. A dissection was performed to release the soft tissue and bone up to 1cm above and below the joint while preserving the posterior capsule. The samples were then decalcified in 10% nitric acid, embedded in paraffin wax, and sectioned in the parasagittal plane to obtain representative sections of the central and lateral regions of the joint. Lateral sections were considered adequate if the posterior horn of the meniscus, the tibial plateau, and the femoral condyle were visible. The central sections had to show both cruciate ligaments. Haematoxylin–eosin and Masson's trichrome stains were performed in both regions for each knee, resulting in a total of four stained sections per knee. Images were digitised at 20× magnification using an optical microscope (Zeiss, Germany) and a high-resolution capture system. The thickness of the posterior capsule was measured on a line perpendicular to the patellar tendon, crossing as close as possible to the centre of the femorotibial space.41 The area of posterior capsular tissue was determined by manually contouring its boundaries (Fig. 2).

Sample size calculation and data analysisStatistical analysis was performed using SPSS 30.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The sample size was calculated for the biomechanical study, considering a type II error of 5%, a power of 80%, a minimum detectable difference of 20°, and an SD of 15°. With an adjustment for an estimated loss of 10%, a sample of 10 rats per group was determined. As knees cannot be reused for both analyses (biomechanical and histological), the sample size was doubled to 20 rats: 10 for the biomechanical analysis and 10 for the histological analysis. The normality of the quantitative variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Variables with a normal distribution were expressed as the mean and SD; those with a non-normal distribution were expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR). To compare baseline characteristics of the sample, the χ2 or Fisher's test was used for qualitative variables and Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney U test for independent quantitative variables, depending on their distribution. For paired variables, repeated measures ANOVA was used, with Bonferroni correction applied where necessary. The model's ability to generate stiffness and fibrosis was evaluated by comparing operated knees and controls using a paired samples t-test or a Wilcoxon test, depending on the distribution. To compare our results with those of Owen, we calculated 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) from the standard error for the variables common to both studies (biomechanical: PEA-2, PEA-4, PEA-8; histological: area and thickness of the posterior capsule), following the principles of statistical inference. The data from Owen's study were extracted from his original publication. To compare the variability between samples, we analysed the ratio between standard errors (SE0:SE1) and the coefficient of variation (CV) of each measurement. Finally, a ROC (receiver operating characteristic) curve analysis was performed to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of the quantitative methods used, determining the area under the curve (AUC) and the optimal threshold value using the Youden index. The level of statistical significance was set at p<.05.

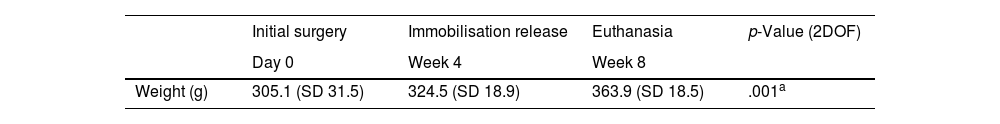

ResultsFollow-up: weight gain and lossesAll rats gained weight adequately after each surgery (Table 1). One rat died during the first week due to overgrown incisors, which made feeding difficult. Five additional knees (3 from the operated group and 2 from the control group) were excluded due to problems during processing and biomechanical analysis or during histological fixation. This resulted in a total loss of 7 knees during the study (17.5%). Three animals (15%) presented immobilisation failures at the time of removal, in the form of broken or loosened suture knots. These animals were not excluded, and an intention-to-treat analysis was performed. The three failures occurred in knees with less than 140° of flexion at the time of the initial surgery (p=.036).

Weight gain during the experiment.

| Initial surgery | Immobilisation release | Euthanasia | p-Value (2DOF) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | Week 4 | Week 8 | ||

| Weight (g) | 305.1 (SD 31.5) | 324.5 (SD 18.9) | 363.9 (SD 18.5) | .001a |

2DOF: two-degree of freedom test.

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation (SD).

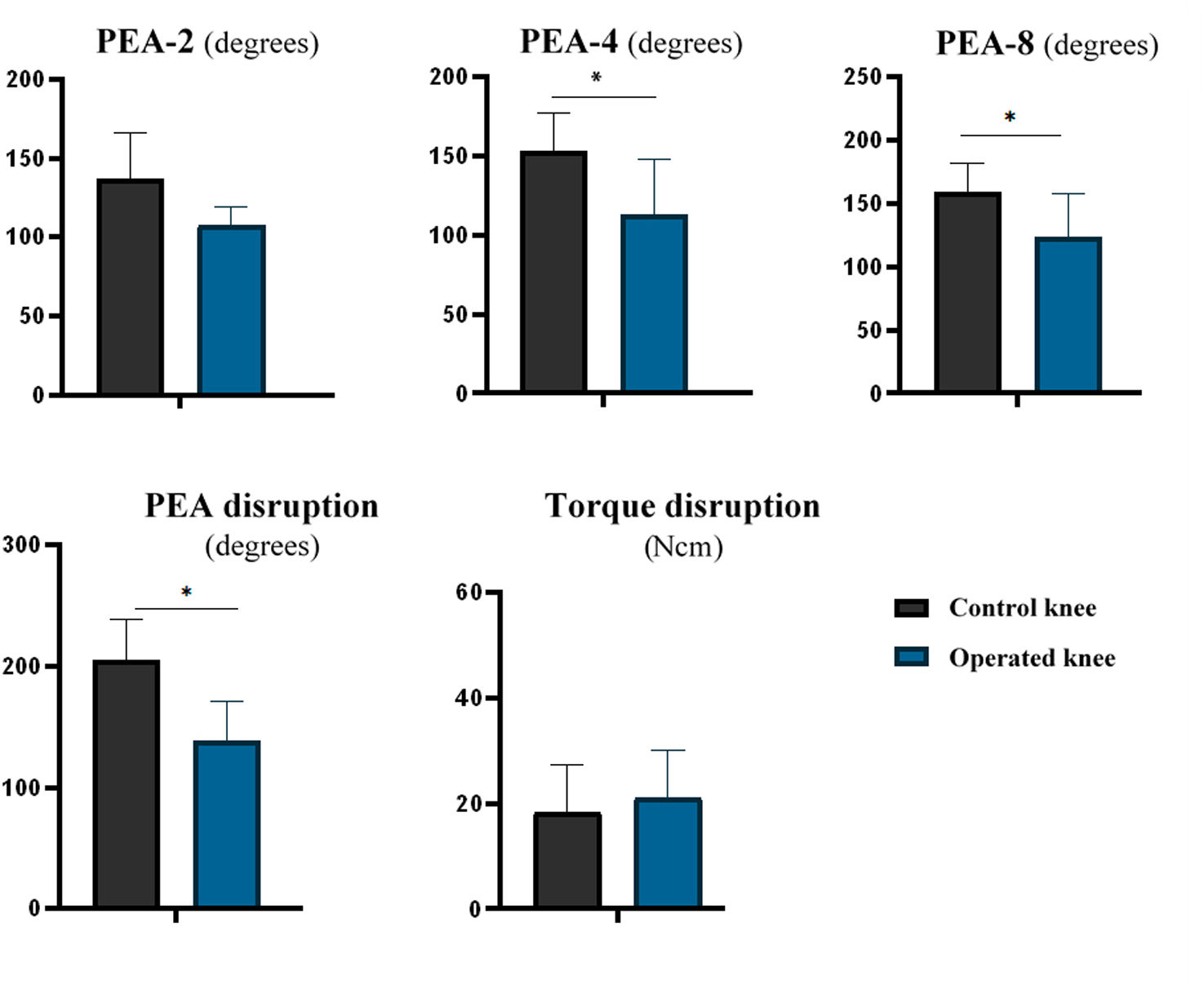

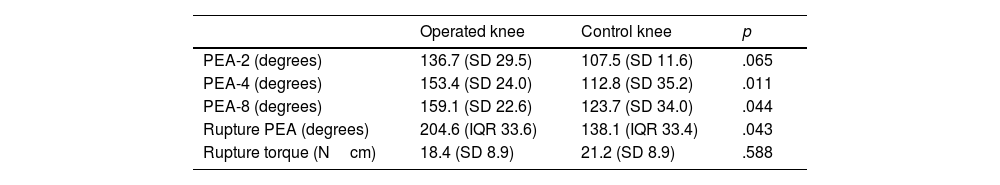

The operated knees had lower PEA-4 (mean difference: 40.6° [95% CI: 12.2–69.0; p=.011]) and PEA-8 (mean difference: 45.6° [95% CI: 13.43–77.45; p=.044]) values compared to the control knees. However, no statistically significant differences were observed for PEA-2 (mean difference: 28.3° [95% CI: −4.6 to 61.1; p=.082]). The operated knees had lower PEA values at capsular disruption than the control knees (median: operated=138.1° [IQR: 33.4] vs. control=204.6° [IQR: 33.6]; p=.043). There were no differences observed in torque at capsular disruption (mean difference: 2.75Ncm [95% CI: −14.10 to 8.59; p=.588]) (Table 2 and Fig. 3).

Biomechanical results.

| Operated knee | Control knee | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEA-2 (degrees) | 136.7 (SD 29.5) | 107.5 (SD 11.6) | .065 |

| PEA-4 (degrees) | 153.4 (SD 24.0) | 112.8 (SD 35.2) | .011 |

| PEA-8 (degrees) | 159.1 (SD 22.6) | 123.7 (SD 34.0) | .044 |

| Rupture PEA (degrees) | 204.6 (IQR 33.6) | 138.1 (IQR 33.4) | .043 |

| Rupture torque (Ncm) | 18.4 (SD 8.9) | 21.2 (SD 8.9) | .588 |

Values are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) or mean and standard deviation and interquartile range (IQR).

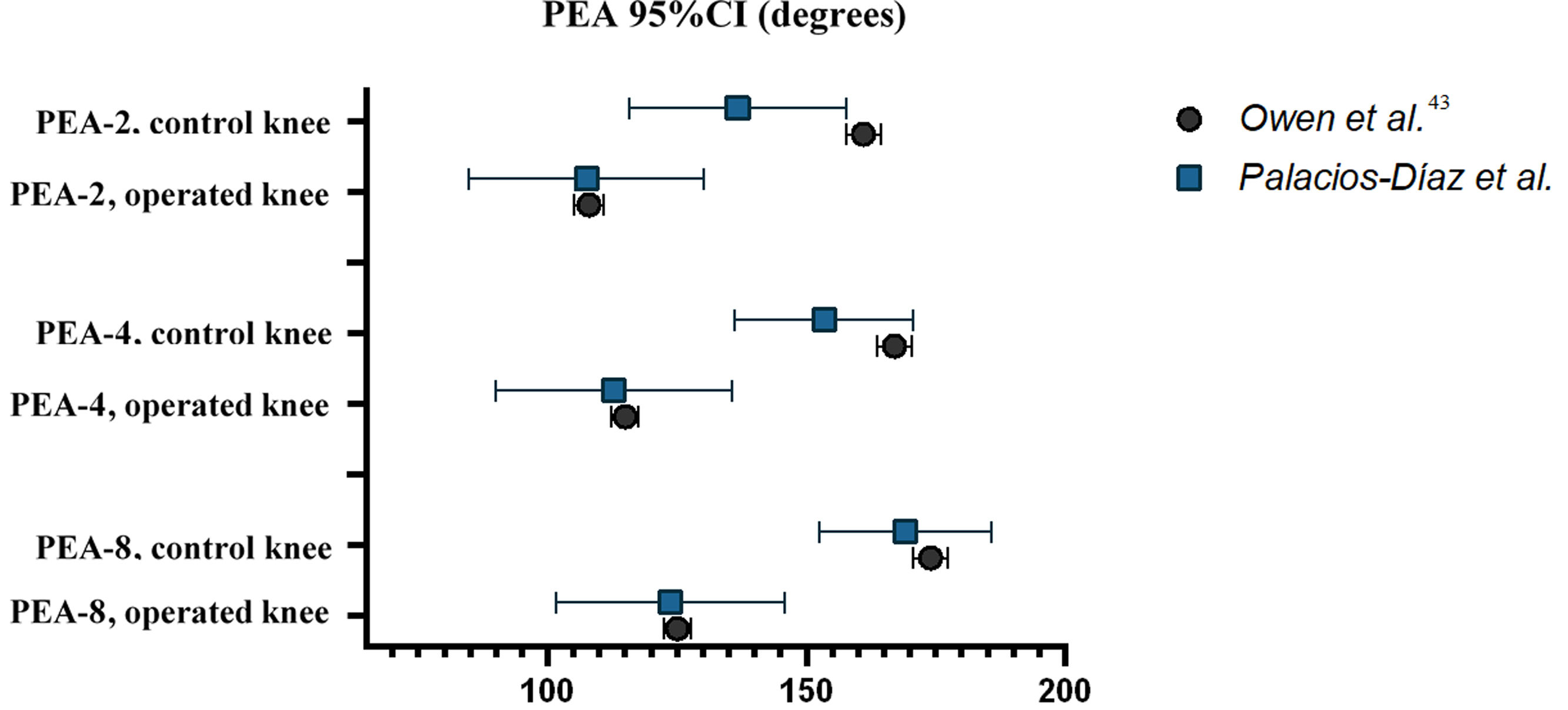

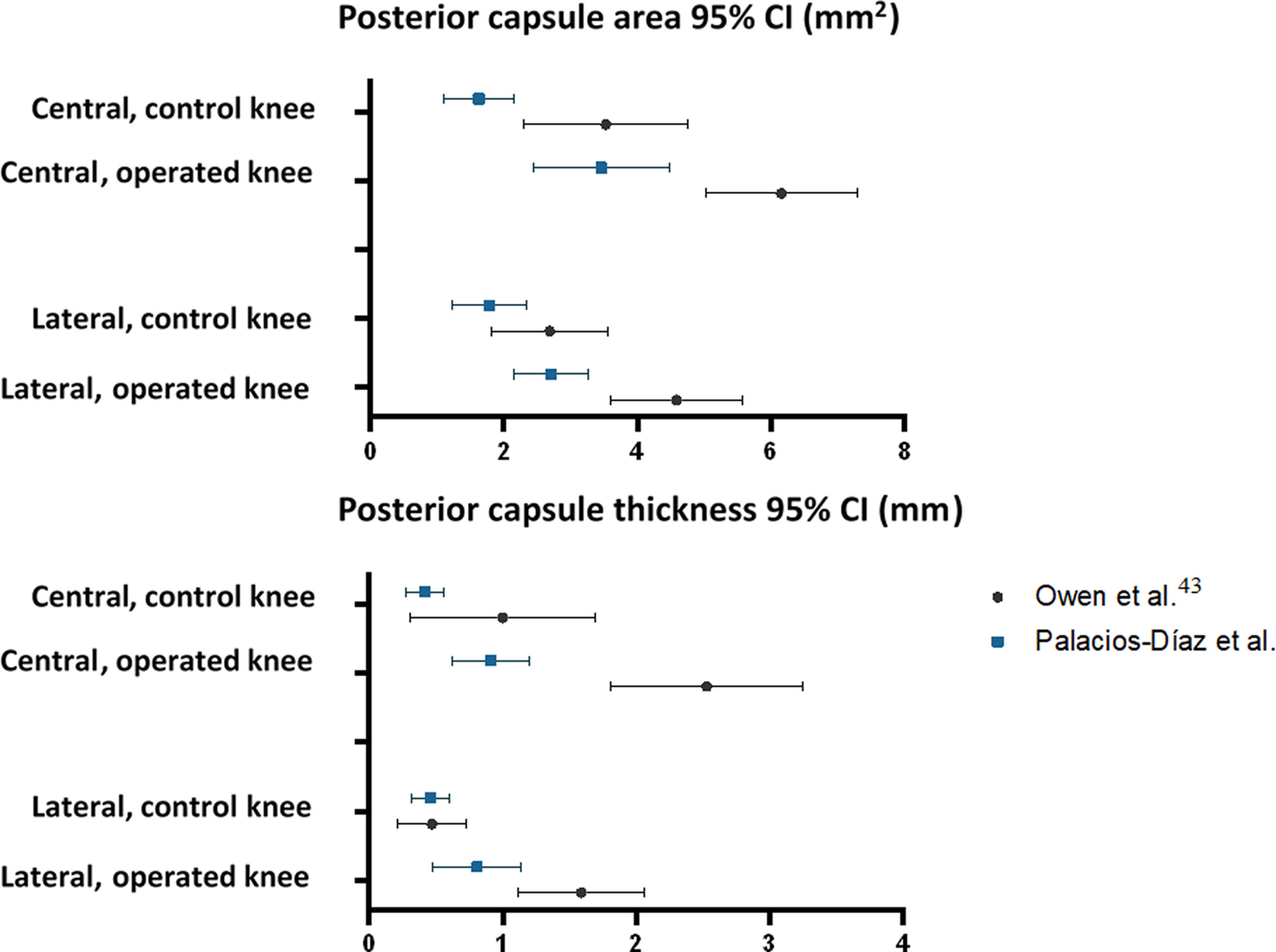

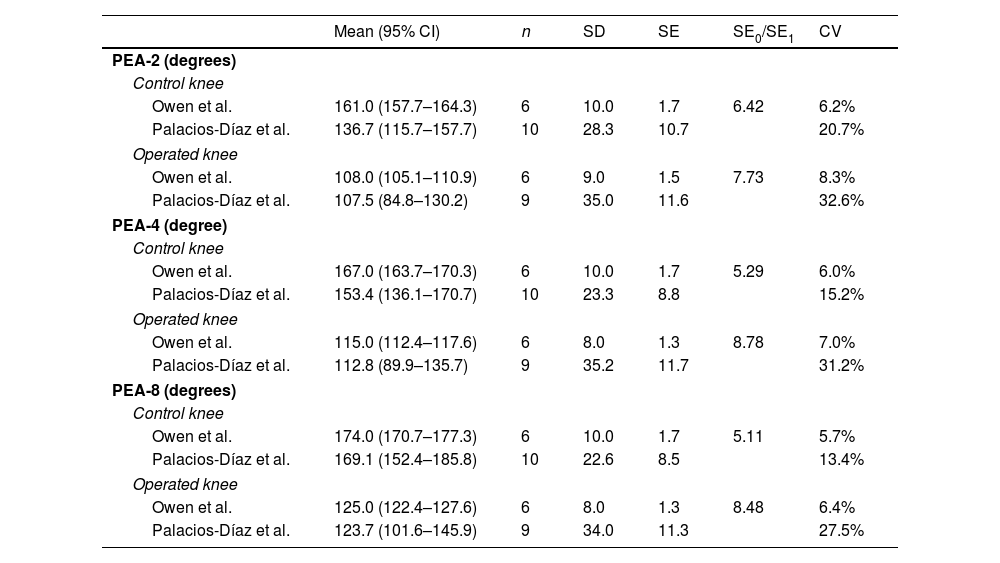

The mean values of PEA-2, PEA-4, and PEA-8 for the operated and control knees in our sample are similar to those published by Owen et al. Furthermore, all 95% CIs in our sample overlap with the 95% CIs in Owen et al.’s sample, except for the upper limit of PEA-2 in the control knees. However, the standard error of our sample (SE0) is greater than that published by Owen et al. (SE1), with a mean SE0/SE1 ratio of 6.97 (range: 5.11–8.78). The mean coefficient of variation (CV0: 23.4%) is also greater than that of the Owen et al.’s sample (CV1: 6.6%). This reflects greater variability in our biomechanical measurements (Table 3 and Fig. 4).

Reproducibility of biomechanical results.

| Mean (95% CI) | n | SD | SE | SE0/SE1 | CV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEA-2 (degrees) | ||||||

| Control knee | ||||||

| Owen et al. | 161.0 (157.7–164.3) | 6 | 10.0 | 1.7 | 6.42 | 6.2% |

| Palacios-Díaz et al. | 136.7 (115.7–157.7) | 10 | 28.3 | 10.7 | 20.7% | |

| Operated knee | ||||||

| Owen et al. | 108.0 (105.1–110.9) | 6 | 9.0 | 1.5 | 7.73 | 8.3% |

| Palacios-Díaz et al. | 107.5 (84.8–130.2) | 9 | 35.0 | 11.6 | 32.6% | |

| PEA-4 (degree) | ||||||

| Control knee | ||||||

| Owen et al. | 167.0 (163.7–170.3) | 6 | 10.0 | 1.7 | 5.29 | 6.0% |

| Palacios-Díaz et al. | 153.4 (136.1–170.7) | 10 | 23.3 | 8.8 | 15.2% | |

| Operated knee | ||||||

| Owen et al. | 115.0 (112.4–117.6) | 6 | 8.0 | 1.3 | 8.78 | 7.0% |

| Palacios-Díaz et al. | 112.8 (89.9–135.7) | 9 | 35.2 | 11.7 | 31.2% | |

| PEA-8 (degrees) | ||||||

| Control knee | ||||||

| Owen et al. | 174.0 (170.7–177.3) | 6 | 10.0 | 1.7 | 5.11 | 5.7% |

| Palacios-Díaz et al. | 169.1 (152.4–185.8) | 10 | 22.6 | 8.5 | 13.4% | |

| Operated knee | ||||||

| Owen et al. | 125.0 (122.4–127.6) | 6 | 8.0 | 1.3 | 8.48 | 6.4% |

| Palacios-Díaz et al. | 123.7 (101.6–145.9) | 9 | 34.0 | 11.3 | 27.5% | |

CV: coefficient of variation; SD: standard deviation; SE0: standard error of our sample; SE1: standard error of Owen et al.’s sample; n: sample size.

95% confidence intervals calculated using the standard error of the mean for PEA-2, PEA-4, and PEA-8 from the original study by Owen et al. and our study (referred to as Palacios-Díaz et al.).

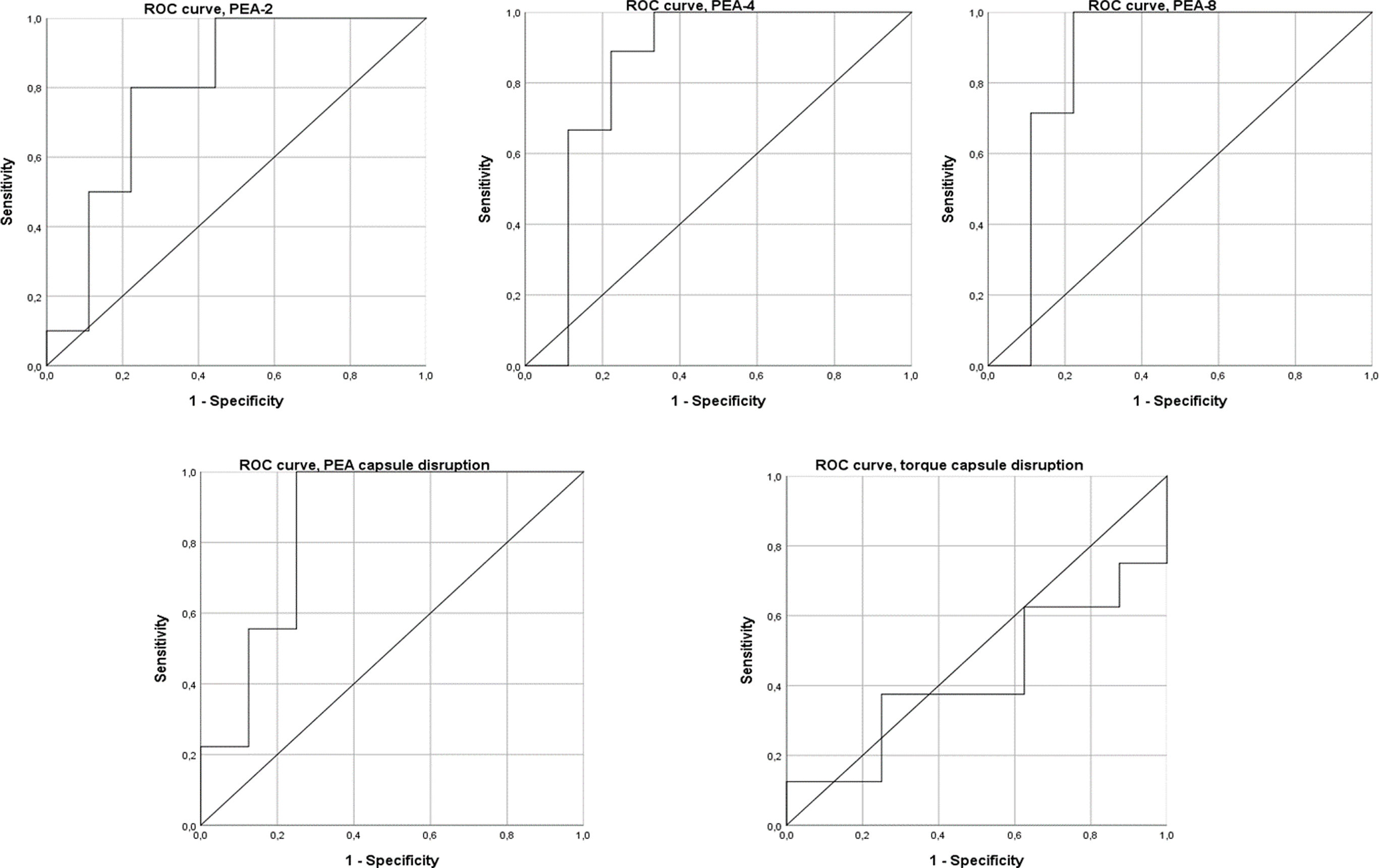

The ROC curve analysis shows that PEA-4, PEA-8, and PEA at capsular disruption are good predictors of arthrofibrosis, while PEA-2 is an acceptable predictor. However, torque at capsular disruption had no discriminatory capacity. PEA-2 showed an AUC of .76 (95% CI: .52–1.00), with a threshold of 103.1° offering 100% sensitivity and 55.6% specificity. PEA-4 had an AUC of .83 (95% CI: .60–1.00), with a threshold of 115.5° offering 100% sensitivity and 66.7% specificity. PEA-8 demonstrated the highest predictive value with an AUC of .86 (95% CI: .64–1.00) and a threshold of 133.60°, and 100% sensitivity and 88.9% specificity. PEA at capsular disruption demonstrated an AUC of .85 (95% CI: .64–1.00), with a threshold of 155.8° offering 100% sensitivity and 75.0% specificity. Torque at capsular disruption showed an AUC of .53 (95% CI: .21–.85) (Fig. 5).

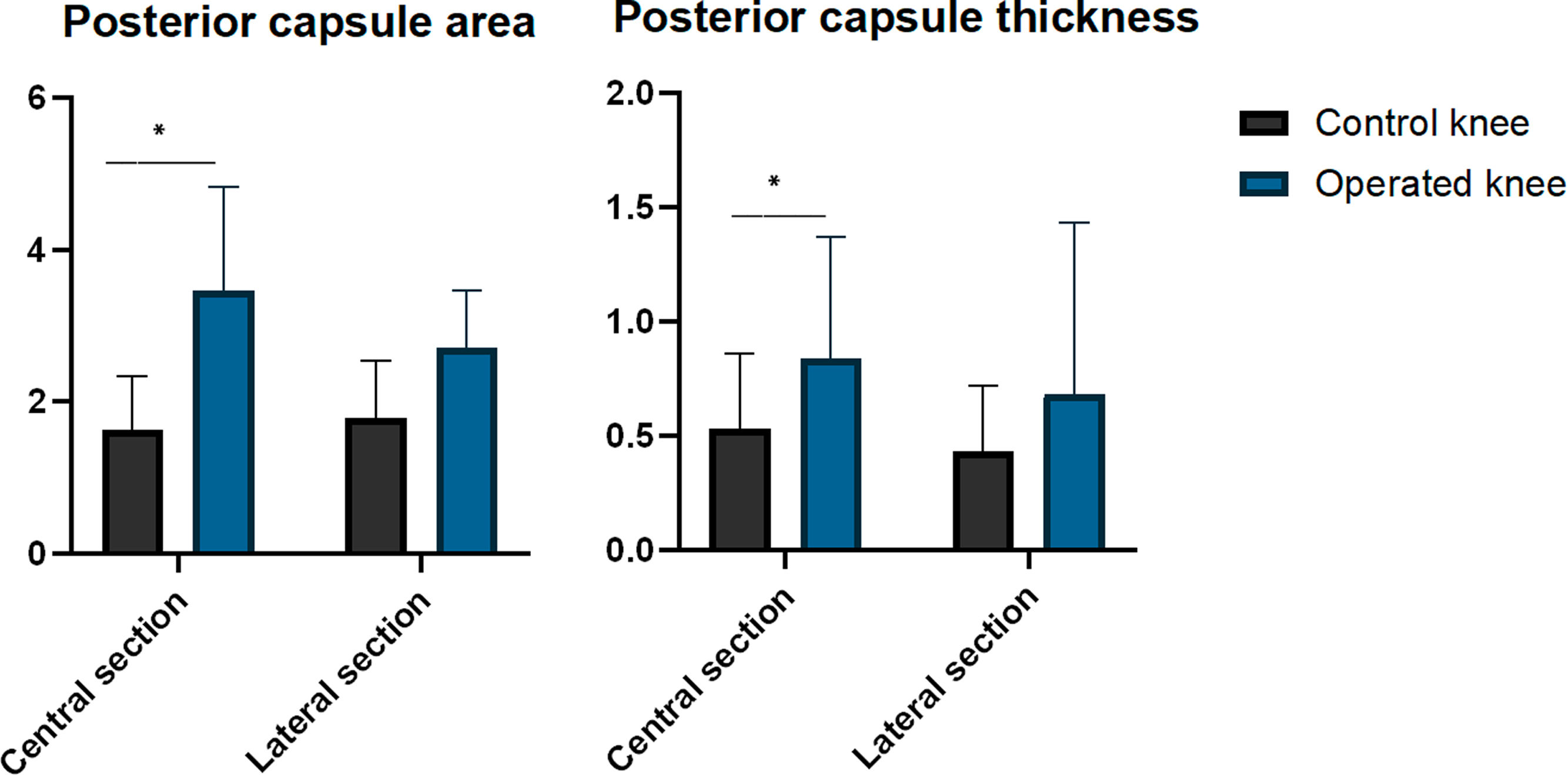

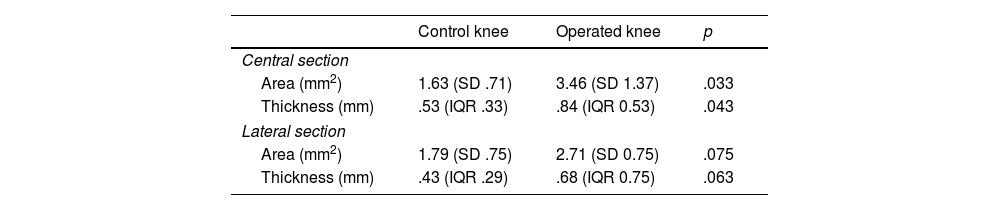

Histological resultsWhen evaluating the central section, the operated knees showed a larger posterior capsule area compared to the control knees (mean difference: 1.82 mm2 [95% CI: .21–3.44; p=.033]). However, there were no significant differences were observed when evaluating the lateral section (mean difference: 9.16 mm2 [95% CI: −.12 to 1.96; p=.075]). The operated knees showed greater posterior capsule thickness than the control knees in the central section (median: operated=.84mm [IQR: .53] vs. control=.53mm [IQR: .33]; p=.043). However, the differences were not significant in the lateral section (median: operated=0.68mm [CI: 0.75] vs. control=.43mm [CI: .29]; p=.063) (Table 4 and Fig. 6).

Histological results.

| Control knee | Operated knee | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central section | |||

| Area (mm2) | 1.63 (SD .71) | 3.46 (SD 1.37) | .033 |

| Thickness (mm) | .53 (IQR .33) | .84 (IQR 0.53) | .043 |

| Lateral section | |||

| Area (mm2) | 1.79 (SD .75) | 2.71 (SD 0.75) | .075 |

| Thickness (mm) | .43 (IQR .29) | .68 (IQR 0.75) | .063 |

Values are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR).

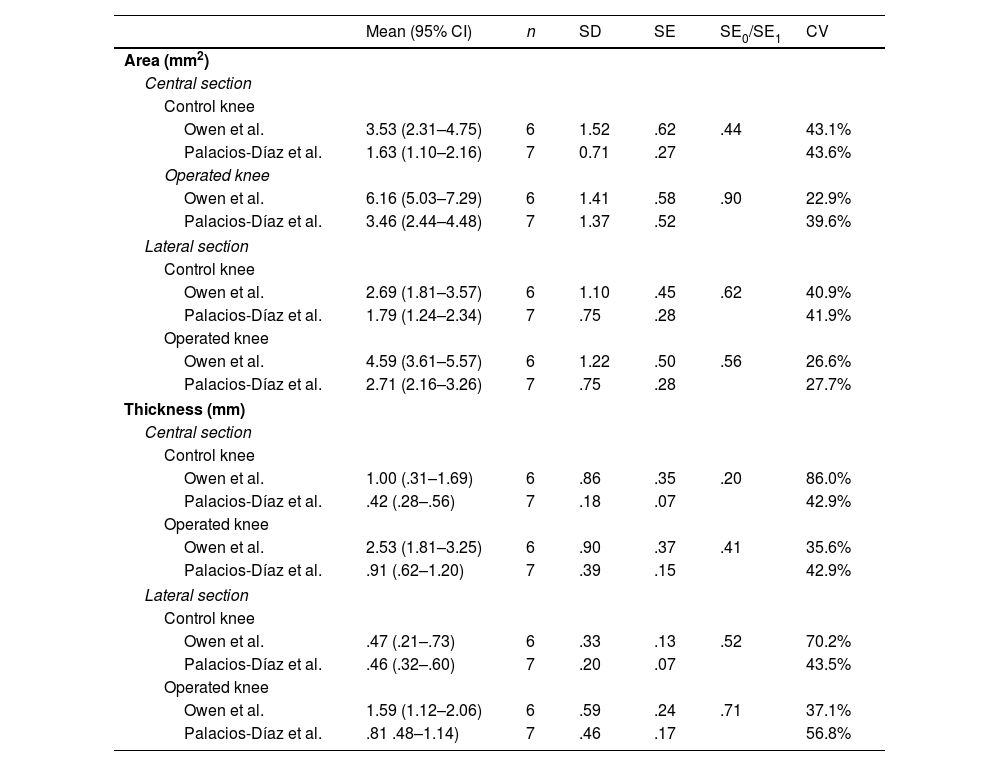

The mean area and thickness of the posterior capsule in the central and lateral sections of the operated and control knees in our sample generally do not coincide with those published by Owen et al. Of the eight possible pairs of 95% CI, only one (thickness of the lateral section in control knees) showed complete overlap between the study by Owen et al. and ours. In 3 cases there was partial overlap, and in the remaining 4 there was none. However, the standard error of our sample (SE0) was lower than that published by Owen et al. (SE1), with a mean SE0/SE1 ratio of .54 (range: .20–.90), and the CV0 was lower (42.3% vs. 45.3%), reflecting less variability in our histological measurements (Table 5 and Fig. 7).

Reproducibility of the histological results.

| Mean (95% CI) | n | SD | SE | SE0/SE1 | CV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (mm2) | ||||||

| Central section | ||||||

| Control knee | ||||||

| Owen et al. | 3.53 (2.31–4.75) | 6 | 1.52 | .62 | .44 | 43.1% |

| Palacios-Díaz et al. | 1.63 (1.10–2.16) | 7 | 0.71 | .27 | 43.6% | |

| Operated knee | ||||||

| Owen et al. | 6.16 (5.03–7.29) | 6 | 1.41 | .58 | .90 | 22.9% |

| Palacios-Díaz et al. | 3.46 (2.44–4.48) | 7 | 1.37 | .52 | 39.6% | |

| Lateral section | ||||||

| Control knee | ||||||

| Owen et al. | 2.69 (1.81–3.57) | 6 | 1.10 | .45 | .62 | 40.9% |

| Palacios-Díaz et al. | 1.79 (1.24–2.34) | 7 | .75 | .28 | 41.9% | |

| Operated knee | ||||||

| Owen et al. | 4.59 (3.61–5.57) | 6 | 1.22 | .50 | .56 | 26.6% |

| Palacios-Díaz et al. | 2.71 (2.16–3.26) | 7 | .75 | .28 | 27.7% | |

| Thickness (mm) | ||||||

| Central section | ||||||

| Control knee | ||||||

| Owen et al. | 1.00 (.31–1.69) | 6 | .86 | .35 | .20 | 86.0% |

| Palacios-Díaz et al. | .42 (.28–.56) | 7 | .18 | .07 | 42.9% | |

| Operated knee | ||||||

| Owen et al. | 2.53 (1.81–3.25) | 6 | .90 | .37 | .41 | 35.6% |

| Palacios-Díaz et al. | .91 (.62–1.20) | 7 | .39 | .15 | 42.9% | |

| Lateral section | ||||||

| Control knee | ||||||

| Owen et al. | .47 (.21–.73) | 6 | .33 | .13 | .52 | 70.2% |

| Palacios-Díaz et al. | .46 (.32–.60) | 7 | .20 | .07 | 43.5% | |

| Operated knee | ||||||

| Owen et al. | 1.59 (1.12–2.06) | 6 | .59 | .24 | .71 | 37.1% |

| Palacios-Díaz et al. | .81 .48–1.14) | 7 | .46 | .17 | 56.8% | |

CV: coefficient of variation; SD: standard deviation; SE0: standard error of our sample; SE1: standard error of Owen et al.’s sample; n: sample size.

95% confidence intervals calculated using the standard error of the man for the area and thickness of the posterior capsule from the original study by Owen et al. and our study (referred to as Palacios-Díaz et al.).

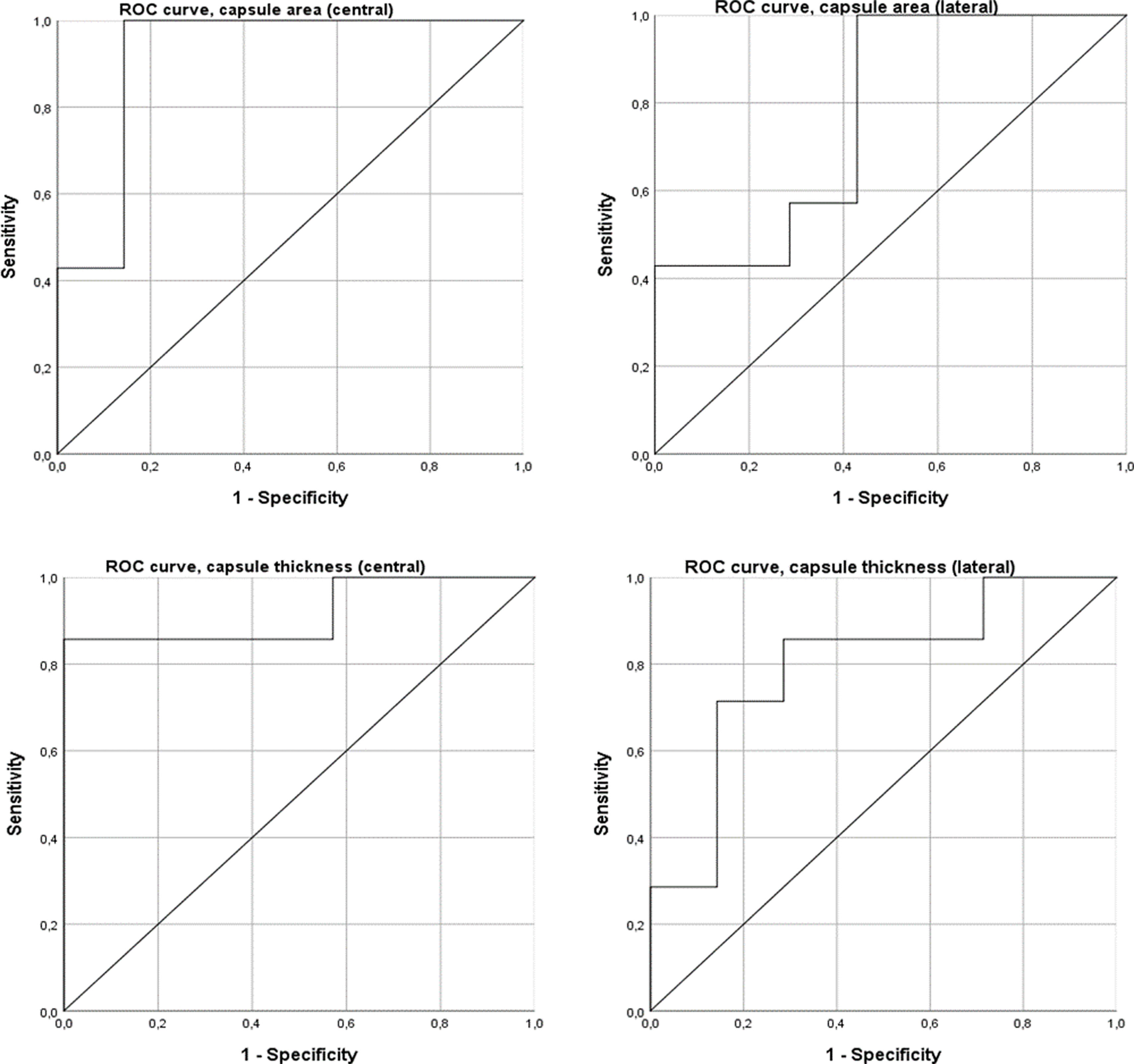

ROC curve analysis showed that the area and thickness of the posterior capsule in the midline section can be classified as excellent predictors of arthrofibrosis, whereas those in the lateral section can be classified as acceptable predictors. The area of the posterior capsule in the midline section had an AUC of .92 (95% CI: .75–1.00), with a threshold of 1.89mm2 offering 100% sensitivity and 85.7% specificity. The thickness of the posterior capsule in the central section showed an AUC of .92 (95% CI: .75–1.00), with a threshold of .61mm offering 85.7% sensitivity and 100% specificity. The area of the posterior capsule in the lateral section showed an AUC of .78 (95% CI: 0.52–1.00), and the thickness in this same section had an AUC of .79 (95% CI: .55–1.00) (Fig. 8).

DiscussionThe main findings of our study are that the operated knees exhibited a smaller passive extension angle at various levels (PEA-4, PEA-8, and PEA at capsular disruption) and a greater posterior capsule area and thickness compared to the control knees. Furthermore, the mean values obtained in our series for PEA-2, PEA-4, and PEA-8 were comparable to those reported by Owen et al.

Based on evidence derived from the most widely used rabbit models, we conclude that the most appropriate model for evaluating drugs in post-traumatic arthrofibrosis should incorporate severe joint injury, periods of immobilisation, and remobilisation. It should also evaluate biomechanical results under standardised torques and histological results using quantitative measurements.17,19,23–26

Severe joint injury involving open surgery to directly damage bone and indirectly damage the joint capsule, followed by immobilisation, causes permanent loss of joint motion. This closely resembles the pathophysiology of post-traumatic arthrofibrosis in humans.17,19,24,26. In contrast, non-traumatic or mild injury models result in joint stiffness that normalises after a period of remobilisation. This makes it difficult to demonstrate significant differences in comparative studies.2,17,18,23,24,42,43 The model described by Owen et al. induces a severe injury that meets all these criteria. Furthermore, the validity of this model is supported by both our results and those of Owen et al.: it causes biomechanical stiffness and histological capsular fibrosis that does not resolve after a prolonged period of remobilisation.

Some studies have used an immobilisation period of 8 weeks, which supports the idea that this is the peak of fibrous tissue production.44–52 In the study by Owen et al., permanent joint arthrofibrosis was achieved using two different immobilisation periods: 4 weeks and 8 weeks.25 In our study, we validated the 4-week model based on evidence that maximum myofibroblast expression in the joint capsule occurs 2 weeks after trauma.22 Furthermore, previous studies in rats using a 4-week immobilisation period have successfully induced severe and permanent joint stiffness.19,43 In both our study and the original study, severe biomechanical stiffness and histological capsular fibrosis were successfully induced, with sufficient sensitivity to differentiate them from healthy tissue with only 4 weeks of immobilisation. This approach is also more cost-effective than longer periods and improves animal welfare through refining the experimental procedure.

In the original study, the Kirschner wire used in previous models was replaced with a 2.0 stainless steel suture tied around the femur and tibia. This eliminated the risk of fracture associated with the tibial tunnel.17,25 In 2023, Dagneaux et al.38 demonstrated the induction of severe joint stiffness in mice using a new percutaneous immobilisation method involving a 3.0 non-absorbable polypropylene suture around the femur and tibia. A key difference between our study and that of Owen et al. is the adoption of Dagneaux et al.’s immobilisation method,38 replacing the original protocol. The main advantages of this method are that it reduces costs and avoids the additional lateral incision required by the Owen et al. procedure, thus refining the animal model and avoiding an extra scar that could act as a confounding factor. Our results, together with those of other authors, confirm the effectiveness of this percutaneous method, as the generated joint stiffness is severe and clearly distinguishable from the controls.53 Surprisingly, the risk of polypropylene suture rupture appears to be lower than that of stainless steel sutures, according to the literature and our results.25,38,53 Furthermore, in our study, suture rupture was associated with an insufficient immobilisation angle, suggesting that ensuring complete flexion immobilisation could prevent this complication. Dagneaux et al.38 reported foot necrosis as the main complication in mice, with an incidence of 4.2%. This was not observed in our study, possibly due to rats being larger than mice.

Models validated in rabbits use a standardised torque of 20Ncm to measure PEA.17,23,24 However, this standardisation has not yet been implemented in rat models, which is a fundamental issue. Several studies in rats have shown that torques of 2, 3.5, or 4Ncm allow differentiation between operated and non-operated joints.26 In this regard, the torques used in our study (2, 4, and 8Ncm) are the same as in the original study, and represent a range exposing the control limbs to both physiological (0°–170°) and supraphysiological (>170°) ranges. Statistically significant differences were demonstrated between the experimental and control joints, except at 2Ncm in our study.25 Using a torque of 8Ncm appears to be the most appropriate, as it has demonstrated the greatest predictive capacity in both studies.25

Our study also measured both PEA and torque at the point of rupture of the posterior capsule.39,40 PEA at rupture was lower in the operated knees, which reinforced the model's ability to induce stiffness. However, rigid and fibrous tissues are less physiological and may therefore be more fragile, requiring less force to break. This could have reduced our ability to detect differences in torque. We believe that analysing the curves at predetermined cut-off points provides a more comprehensive and detailed view of mechanical behaviour and joint stiffness than focusing on the exact torque value.

The greater variability in our biomechanical results could be explained by methodological differences compared to the study by Owen et al. As both operated and control knees are affected, differences cannot be attributed to the use of polypropylene sutures instead of steel for immobilisation. Therefore, the lack of precision in the biomechanical measurements appears to be the main source of variability. Owen et al. used a machine designed by engineers at the Biomechanics Lab Core Facility at the Mayo Clinic (Minnesota, USA), whereas ours was manufactured by Servosis (Madrid, Spain).25 This difference could explain the disparity in precision. Furthermore, in the original study, the knee was fixed directly to a metal piece; in our study, however, a 3D-printed support made of polylactic acid (PLA), a bioplastic that deforms more easily than metal, was used. This could also have influenced the results.54 Despite this variability, statistically significant differences were found, supporting the validity of the experimental model.

In the study by Owen et al., it was found that the central sections demonstrated the best predictive capacity.25 Our results support this finding, as differences between operated and non-operated knees were only observed in these sections. Therefore, the central sagittal section, which is easily identifiable by the cruciate ligaments, should be considered the primary section for assessing posterior capsular fibrosis.25 In the original study, medial sections exhibited less fibrosis than central and lateral sections. The cause is unclear, but the combination of lateral parapatellar arthrotomy and the inflammatory response to intra-articular trauma could generate a more intense reaction in the central and lateral capsular areas. For this reason, and to reduce costs, we decided not to include medial sections.

To improve the precision and reproducibility of fibrous tissue evaluations, the original study used quantitative and objective histological measurements instead of qualitative or semi-quantitative methods. Furthermore, previous studies have been limited to linear measurements in a sagittal section.18,19 In the study by Owen et al., although linear measurements (posterior capsular thickness) revealed differences, their predictive capacity was lower than that of two-dimensional measurements (posterior capsular area), as indicated by ROC curves, which offer greater sensitivity and specificity.25 In our sample, however, no such differences were observed, as both area and thickness in central sections showed excellent predictive capacity. In contrast, measurements in the lateral section showed lower predictive capacity, with no differences between operated and non-operated knees. This may be due to greater variability when measuring the lateral section, as it is difficult to distinguish the boundaries between the posterior edge of the lateral meniscus and the posterior capsule, the latter being a capsular extension.55,56 Further studies are needed to refine this measurement and provide a more objective definition.

Despite achieving greater precision in our histological measurements (in central and lateral sections), we were unable to demonstrate the reproducibility of these variables: the confidence intervals between the two studies differ considerably. We believe that greater standardisation of histological processing and measurement methods is required. For example, the boundaries of the capsule must be clearly defined. In addition to the lateral meniscus, the boundary between the fibrous membrane of the capsule and its continuity with the periosteal membrane must be precisely established. Previous studies have also established a 90° angle of flexion for sample processing, which allows for more homogeneous folding of soft tissues such as the capsule.30,57

In our study, animal mortality was low, although total limb loss was slightly higher than that reported globally in preclinical models of post-traumatic arthrofibrosis.26 However, the procedure is considered safe, as the rats gained weight adequately after surgery and no intraoperative deaths were recorded, unlike the overall loss of 12% due to fractures or anaesthesia. Limb loss during processing or measurements was slightly higher in our study (although close to 10%), mainly due to fractures during biomechanical testing, histological errors, or extreme outlier values.26 Such complications are common in animal experimentation.58,59

Another limitation of our study is that we did not assess the integrity of the articular cartilage. Owen et al. demonstrated degenerative changes in the cartilage of operated knees, which could affect the interpretation of results relating to arthrofibrosis.25 This appears to be a phenomenon that occurs in rats, but not in other animal models, possibly because rats bear weight on the injured limb immediately after surgery. While this does not preclude the use of rats in research, it should be carefully considered when interpreting the results.60,61

This study has certain limitations and strengths that should be noted. Notably, there was greater variability in the biomechanical results compared to previous studies, which is probably due to differences in the methodology, measuring devices and materials used to fix the limb. Furthermore, the integrity of the articular cartilage was not evaluated, which could be a significant factor affecting the interpretation of the findings. Medial histological sections were not included either, meaning the reproducibility of the histological measurements could not be demonstrated. This could be due to a lack of standardisation in processing and defining the capsule boundaries. Although expected in this type of model, the loss of limbs during the study was slightly higher than that reported in the literature. Despite these limitations, our results demonstrate that the post-traumatic arthrofibrosis model described by Owen et al. can induce biomechanical stiffness (assessed as PEA-4, PEA-8, and PEA at capsular disruption) even after free mobility. In addition, histological capsular fibrosis differed between the operated and control knees, both in one dimension (thickness) and in two (area) on evaluating the central section. Adopting the percutaneous immobilisation method described by Dagneaux et al.38 represents a technical improvement that reduces costs, avoids an additional incision and refines the animal model. Despite greater variability in biomechanical results, our findings are comparable to those of Owen, which supports the reproducibility of the model from a biomechanical point of view.

We favour a rat model of post-traumatic arthrofibrosis that includes severe joint injury, percutaneous immobilisation for 4 weeks, fixation of the limb directly to a metal piece on a biomechanical machine, and biomechanical analysis at predetermined torque cut-off points, especially at 8Ncm. We also evaluate central histological sections using two-dimensional measurements, such as the area of the posterior capsule. We believe that greater standardisation of processing and histological measurement methods is required.

ConclusionThe post-traumatic arthrofibrosis model described by Owen et al. successfully induces biomechanical stiffness and persistent histological capsular fibrosis. Adopting the percutaneous immobilisation method proposed by Dagneaux et al. represents a significant improvement as it helps to refine the animal model. Our results confirm the reproducibility of this model from a biomechanical point of view, thereby reinforcing its usefulness in preclinical research on post-traumatic arthrofibrosis.

Level of evidenceLevel V evidence.

Ethical considerationsThe research was approved by the hospital's Ethics Committee. Informed consent was obtained from all patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is held by the corresponding author.

FundingThis project was funded by the 17th SECEC (Société Européenne pour la Chirurgie de l’Épaule et du Coude) 2023 Basic Research Grant and the Spanish Society of Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology (SECOT) 2024 Grant for Research Projects in Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.