and aim Surgical techniques that try to correct the three-dimensional deformity of hallux valgus is becoming more and more frequent with the hope of achieving better outcomes. The aim of this study was to assess the radiological parameters of correction in transverse and frontal planes as well as clinical outcomes of hallux valgus patients undergoing a 4th generation MIS technique.

Patients and methodsSeventy-seven feet in 77 patients with hallux valgus deformity were treated with a 4th generation minimally invasive technique which allowed frontal plane correction with a follow up of 12 months. Preoperative and postoperative anteroposterior weightbearing X-ray images were analysed including hallux valgus angle, intermetatarsal angle, tibial sesamoid position and frontal plane first metatarsal rotation by means of a classification into four groups. Clinical outcomes were measured using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), the American Orthopaedic Foot Ankle Society (AOFAS) hallux MTF-IF questionnaire, and EuroQol (EQ5D5L and EQVAS) prior to surgery and one year of follow-up.

ResultsThere were statistical significant differences in the four radiological variables (p<0.001) with a mean correction of 23.5±9.6° in hallux valgus angle, 7.0±3.5° in intermetatarsal angle, 2.6±1.3 in tibial sesamoid position and a change of 1.4±0.9 in first metatarsal pronation classification. There was a significant improvement in all the clinical parameters measured. The complication rate was 18.8% and 2.6% required reoperation.

ConclusionsThe proposed MIS technique has shown to be a potential method for correction of hallux valgus in the transverse and frontal plane with a low complication rate, patient satisfaction and an improvement in quality of life.

Las técnicas quirúrgicas que tratan de corregir la deformidad tridimensional del hallux valgus son cada vez más frecuentes para intentar conseguir una corrección funcional y duradera. El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar los parámetros radiológicos de corrección en planos transversal y frontal, así como los resultados clínicos de pacientes con hallux valgus sometidos a una técnica percutánea de 4.a generación.

Pacientes y métodosSetenta y siete pies (77 pacientes) con hallux valgus fueron tratados con una técnica mínimamente invasiva de 4.a generación que permitió la corrección del plano frontal con un seguimiento de 12 meses. Se analizaron las radiografías preoperatorias y posoperatorias anteroposterior en carga incluyendo el ángulo del hallux valgus, ángulo intermetatarsiano, posición del sesamoideo tibial y rotación del primer metatarsiano en el plano frontal mediante una clasificación en cuatro grupos. Los resultados clínicos fueron medidos mediante la Escala Visual Analógica (EVA), el cuestionario del American Orthopaedic Foot Ankle Society (AOFAS) hallux MTF-IF, y EuroQol (EQ5D5L y EQVAS) previo a la cirugía y al año de seguimiento.

ResultadosHubo diferencias estadísticamente significativas en las cuatro variables radiológicas (p<0,001) con una corrección media de 22,3±9,3° en el ángulo hallux valgus, 6,7±3,8° en el ángulo intermetatarsiano, 2,5±1,3 en la posición del sesamoideo tibial y un cambio de 1,3±0,9 en la clasificación de la pronación del primer metatarsiano. Existió una mejoría significativa en todos los parámetros clínicos medidos. La tasa de complicaciones fue del 18,8% y requirió reintervención del 2,6%.

ConclusionesLa técnica de cirugía mínimamente invasiva (MIS) propuesta es un método eficaz para la corrección del hallux valgus en el plano transversal y frontal con una baja tasa de complicaciones, satisfacción del paciente y una mejoría de la calidad de vida.

Hallux valgus is the most common foot deformity and one of the most difficult to correct. Although it has historically been considered a deformity in the transverse plane, this view has recently been superseded, with the condition now being considered a deformity in three planes (transverse, sagittal, and frontal).1,2 Techniques that take this multiplanar deformity into account, especially in the frontal plane, are currently becoming more common in order to achieve good alignment and a functional, durable correction.3–5 Kim and Young6 estimated that 87% of patients with hallux valgus exhibited some degree of frontal rotation of the first metatarsal, which did not appear to correlate with the extent of transverse plane deformity.

Although countless techniques have been described for correcting hallux valgus, no single surgical procedure is considered the ‘gold standard’. While recent studies show comparable medium- and long-term clinical and radiological results for open and percutaneous surgery,7,8 percutaneous surgery is less invasive for soft tissues. In the short term, this results in less postoperative pain and stiffness, and a lower infection rate.7 Minimally invasive surgery (MIS) techniques, also known as 4th generation techniques, attempt to correct deformities in all planes by manipulating the distal extra-articular osteotomy of the first metatarsal, which is held in place by two screws. However, despite technical modifications to MIS surgery being proposed for correcting deformities in the frontal plane,9 hardly any studies have yet assessed the potential of percutaneous techniques for this purpose. Even fewer studies have considered clinical parameters that assess patient satisfaction with the procedure. It is unclear whether these techniques are a valid option for correcting rotation in the vast majority of patients with hallux valgus.

This study aimed to analyse the radiological and clinical correction capacity, measured using various questionnaires, of an MIS technique for META-type hallux valgus surgery (metaphyseal extra-articular transverse and akin osteotomy), modified to produce correction in the frontal plane.

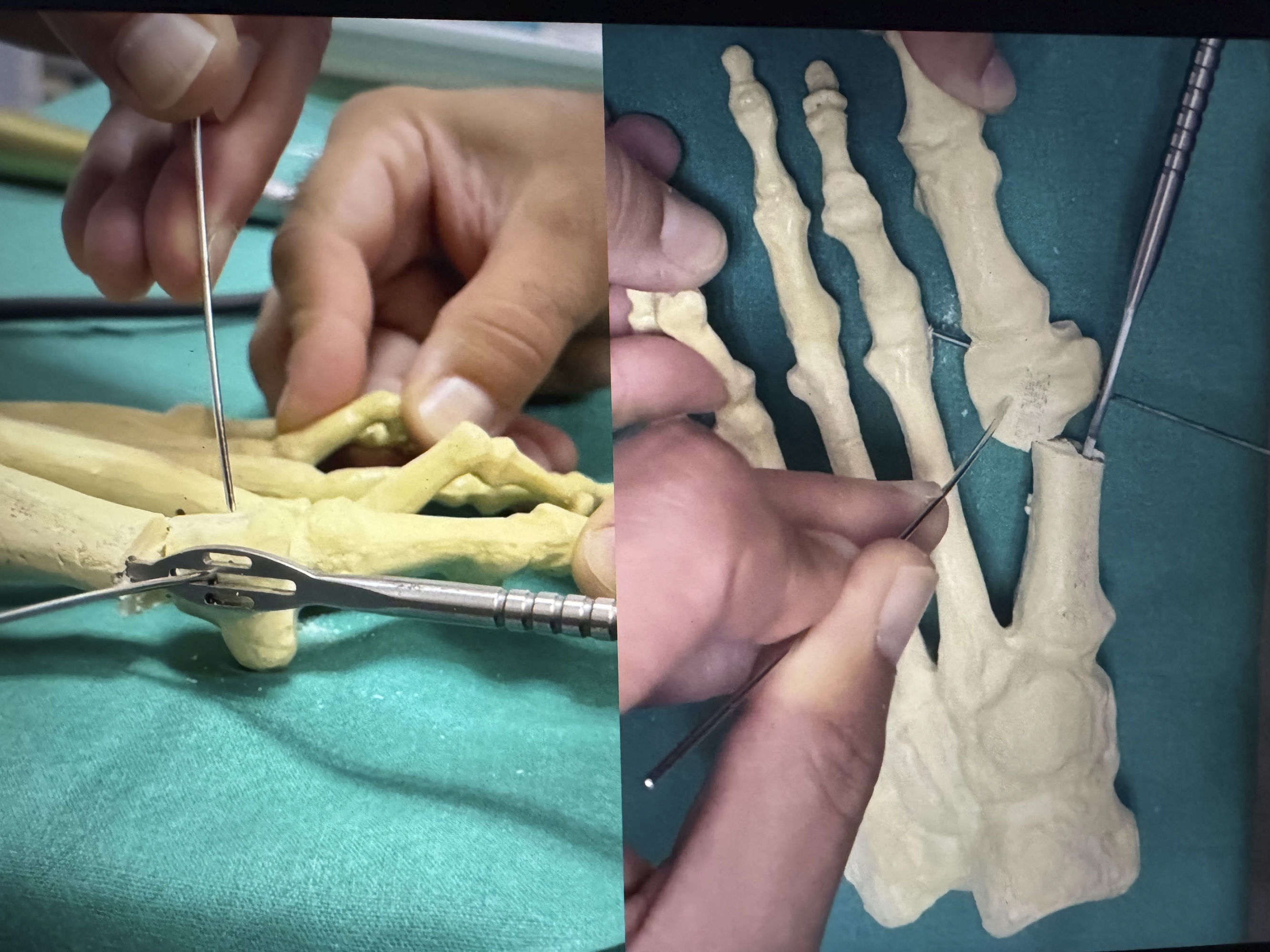

Material and methodsStudy design and locationThis is a prospective, observational, case series study of patients with hallux valgus deformity who were treated using the 4th generation MIS technique with a straight osteotomy to correct the deformity in the frontal plane (Fig. 1), and who were the subject of a previously published study.10 The STROBE guidelines for reporting observational studies were followed when preparing and writing the manuscript.11

Study populationOf all patients who underwent consecutive hallux valgus surgery at the Foot Unit of Basurto University Hospital using the META technique during 2019 and 2020, only those with complete data for the analysed variables (radiological variables prior to surgery and at one year follow-up, and clinical variables prior to surgery, at 6 months, and at one year follow-up) remained in the study.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) patients over 16 years of age with pain and failure of conservative treatment (modification of footwear, protectors, and analgesics) for at least 3 months; and (2) hallux valgus deformity treated with the percutaneous META technique, regardless of the deformity's severity. Patients were excluded if they had previously undergone hallux valgus surgery, had a systemic disease affecting the musculoskeletal system (rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, or gout), had osteoarthritis of the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint, had sagittal instability of the first tarsometatarsal (TMT) joint verified by misalignment or asymmetry on lateral weight-bearing X-ray, or had undergone simultaneous osteotomies of the lesser metatarsals.

Approval for the study was granted by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Bilbao-Basurto Integrated Healthcare Organisation on 20 February 2019. All patients were informed about the nature of the study and signed a consent form to participate.

Variables analysed and measurementsGeneral study variables collected included age, sex, and laterality of the operated foot. Alongside these, the radiological variables of all patients in the study, as measured on preoperative and postoperative AP weight-bearing radiographs at 12 months, were analysed. The AP projection was weight-bearing, with a 15° angulation of the X-ray beam on the foot for all patients. All measurements were performed by the same observers (LFG and RTP) using ICIS View radiological image assessment software (AGFA Healthcare N.V.®, Mortel, Belgium) which allows direct measurement of radiological images using angles on the programme interface. These radiological variables were: (1) the first metatarsophalangeal joint angle (MTPA); (2) the intermetatarsal angle (IMA) between the first and second metatarsals, measured according to the accepted protocol using the diaphysis of the first and second metatarsals and the proximal phalanx12; (3) the position of the sesamoid, as classified by Hardy and Clapham,13 pre- and postoperative (Fig. 2); (4) the degree of pronation of the first metatarsal, analysed according to Wagner's classification of 4 types14,15 (Fig. 3).

Wagner classification into 4 groups. In group 0, there is no metatarsal rotation (no sign of rounding); in group 1 (angular shape), there is an irregular shape of the lateral edge of the head with a separation between the contour of the condyles and the joint line, corresponding to 10°–20° of pronation; in group 2 (intermediate shape) there is partial rounding without separation, corresponding to 20°–30° of pronation; and in group 3 (round shape) the head is completely rounded, which corresponds to pronation >30°.

In addition to radiological variables, the visual analogue scale for pain (VAS) and the assessment of patient-reported outcomes in the PROM (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measures) survey, the AOFAS questionnaire for hallux MTF-IF, and the EuroQol EQ5D5L questionnaire were collected during pre and postoperative consultations. The AOFAS questionnaire awards up to 100 points, with variable weighting, based on subjective and objective data, in three categories: pain, function, and alignment. A score of 91–100 is considered excellent, 80–89 good, 70–79 average, and below 70 poor.16 The EQ5D5L17 consists of 5 items relating to 5 dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression, rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (no problems) to 5 (unable to). The combined dimensions describe 55=3125 theoretically possible health states, which can be converted into a utility index ranging from −.4162 to 1, where a higher score indicates a better health-related quality of life.18 Additionally, the questionnaire includes a visual analogue scale (EQVAS) in which individuals rate their own current health on a scale from 0 (worst imaginable health) to 100 (best imaginable health).

Clinical complications occurring during the follow-up period were finally recorded in the patients’ medical records. The Clavien–Dindo–Sink classification, which has recently been adapted for hallux valgus surgery, was used.19 This classification ranks complications into 3 grades:

- •

Grade 1: adverse effects that do not affect postoperative follow-up.

- •

Grade 2: Complications that do not require surgery or additional hospitalisation.

- •

Grade 3: Complications requiring surgical intervention or hospitalisation.

The reliability analysis was carried out in the previous study10 by 2 of investigators involved in the study. Twenty cases from the study were assessed by the 2 observers to evaluate inter-observer reliability. The same 20 cases were then measured again by one of the observers (RTP) one week later to assess intra-observer reliability.

Surgical techniqueThis is a modification of the MICA (Minimally Invasive Chevron Akin) technique described by Redfern and Vernois,20 in which a straight osteotomy is performed medially at the neck of the first MTT and perpendicular to its sagittal axis using a 2mm×20mm Shannon burr (FH orthopaedics®, Mulhouse, France). The osteotomy is displaced by inserting a periosteotome into the proximal intramedullary canal to act as a lever to push the metatarsal head laterally. Without forcing the displacement to avoid tension on the soft tissues, a K-wire (1.5mm) is inserted percutaneously into the metatarsal head parallel to the osteotomy line and lateral to the extensor hallucis longus (EHL), which can be used as a joystick to correct the pronation of the first metatarsal. Under fluoroscopic control in AP projection, the metatarsal head is rotated until the sign of lateral rounding of the first MTT head disappears and the sesamoids are placed in a centred position. Once this is achieved, the position of the K-wire is maintained while forcing lateral displacement of the head and inserting another temporary K-wire (1.5mm) through the periosteotome (specially designed with a slot) that stabilises the metatarsal head to the second MTT (Fig. 4).

After checking the correctness of the AP and lateral projections, the osteotomy is fixed in place. Initially, two 1.5mm K-wires (smaller ones are too flexible to be directed to the intended location) are inserted from the base of the metatarsal proximally to the metatarsal head, and at least one of them must pass through the lateral cortex of the proximal fragment, which gives the structure greater stability. They are then removed one by one and the guide needle (1mm) for the final screw is inserted into the hole left behind. The material used is specific to this technique: 3mm double-threaded cannulated screws without heads and chamfered to avoid intolerance (45B screw, FH ORTHO®, Heimsbrunn, France).

The bone step at the medial edge caused by the translation of the head is resected using a 2mm×12mm Shannon burr, which is inserted through the proximal incision made for the insertion of the screws.

Next, percutaneous lateral soft tissue release is performed by inserting the Beaver scalpel just lateral to the EHL at the dorsolateral level of the MTP joint and advancing plantarly. The scalpel blade is then rotated and advanced towards the first intermetatarsal space while forcing the varus of the first toe, obtaining the section of the plantar joint capsule and the adductor tendon.

Finally, an incomplete percutaneous Akin osteotomy is performed at the level of the proximal metaphysis of the first phalanx. A 2mm×12mm Shannon burr is used to perform an incomplete osteotomy, leaving the lateral cortex weakened but intact, in order to perform osteoclasia by forcing varus of the first toe. This allows for some stability without the need for osteosynthesis, preventing displacement.

In the postoperative period, a bandage is applied for 5 weeks to help maintain the reduction, and weight-bearing is allowed after 24–48h with orthopaedic footwear with a rigid flat sole (Medsurg post-surgical shoe, DARCO® GmbH, Rainsting, Germany) which must be worn for the same period of time. Clinical monitoring is carried out with a dressing change after one week, 3 weeks, and removal after 5 weeks.

Statistical analysisDescriptive analysis of categorical variables used frequency and percentage, while mean, standard deviation (SD), minimum and maximum values were used for quantitative variables. The non-parametric Wilcoxon test for paired data was used for before and after comparison of the different quantitative variables. To compare qualitative variables, a contingency table was created, and the McNemar–Bowker test for repeated samples was used to analyse changes in category percentages. Reliability analysis was performed on 20 cases using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and inter- and intra-observer agreement analysis for quantitative radiological variables. The Kappa test was performed for qualitative radiological variables (sesamoid position and pronation of the first MTT). A result was considered statistically significant if p<.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS for Windows, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

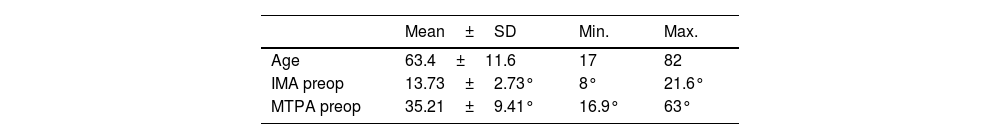

ResultsA total of 77 feet belonging to 77 patients were included in the study. The gender distribution of the data was 12 men (15.58%) and 65 women (84.42%) (see Table 1). Table 1 shows the basic anthropometric data and preoperative angles of the study population.

Descriptive statistics of the sample (N=77).

| Mean±SD | Min. | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 63.4±11.6 | 17 | 82 |

| IMA preop | 13.73±2.73° | 8° | 21.6° |

| MTPA preop | 35.21±9.41° | 16.9° | 63° |

| Mean±SD | Position 1 | Position 2 | Position 3 | Position 4 | Position 5 | Position 6 | Position 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sesamoid PREOP | 5.24±1.17 | 1 (1.3%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2.6%) | 16 (20.78%) | 28 (36.36%) | 17 (22.1%) | 13 (16.88%) |

| Mean±SD | Group 0 (n; %) | Group 1 (n; %) | Group 2 (n; %) | Group 3 (n; %) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronation PREOP | 1.92±.92 | 6 (7.8%) | 18 (23.4%) | 29 (37.6%) | 24 (31.2%) |

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Males | 12 | 15.6% |

| Females | 65 | 84.4% |

| Laterality | ||

| Right | 38 | 49.3% |

| Left | 39 | 50.7% |

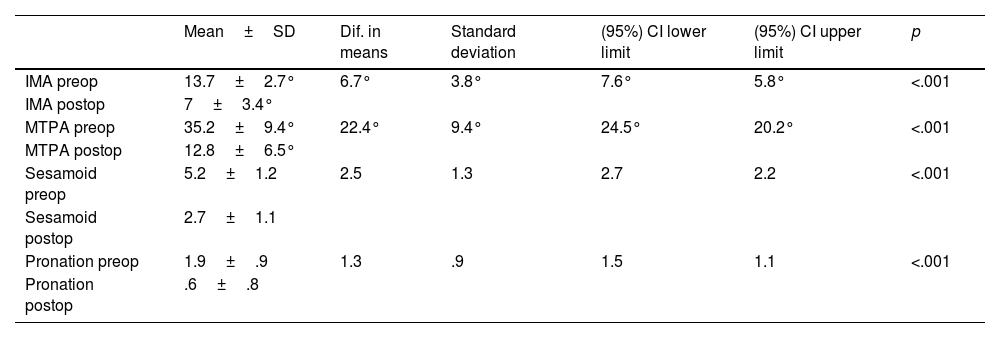

Significant improvements were observed in all radiological parameters compared to the preoperative situation. Table 2 shows the preoperative and postoperative values of the IMA and MTPA angles, as well as the mean pronation values on AP radiography, the position of the sesamoid bones before and after, and the results of the Wilcoxon test and the confidence interval for the difference. Statistically significant differences were found in the mean of the 4 preoperative and postoperative values (Table 2).

Wilcoxon test for paired samples of radiographic variables (N=77).

| Mean±SD | Dif. in means | Standard deviation | (95%) CI lower limit | (95%) CI upper limit | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMA preop | 13.7±2.7° | 6.7° | 3.8° | 7.6° | 5.8° | <.001 |

| IMA postop | 7±3.4° | |||||

| MTPA preop | 35.2±9.4° | 22.4° | 9.4° | 24.5° | 20.2° | <.001 |

| MTPA postop | 12.8±6.5° | |||||

| Sesamoid preop | 5.2±1.2 | 2.5 | 1.3 | 2.7 | 2.2 | <.001 |

| Sesamoid postop | 2.7±1.1 | |||||

| Pronation preop | 1.9±.9 | 1.3 | .9 | 1.5 | 1.1 | <.001 |

| Pronation postop | .6±.8 |

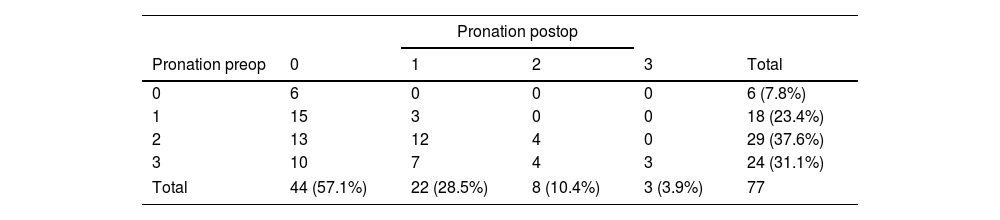

An exact McNemar–Bowker test for repeated samples was performed to assess pre and postoperative changes in the ordinal categorical variables of metatarsal head pronation in AP X-rays and sesamoid bone position in AP X-rays. Statistically significant differences were obtained for the percentages in each group in the preoperative variables compared to the postoperative variables (p<.001 in both tests) (Table 2).

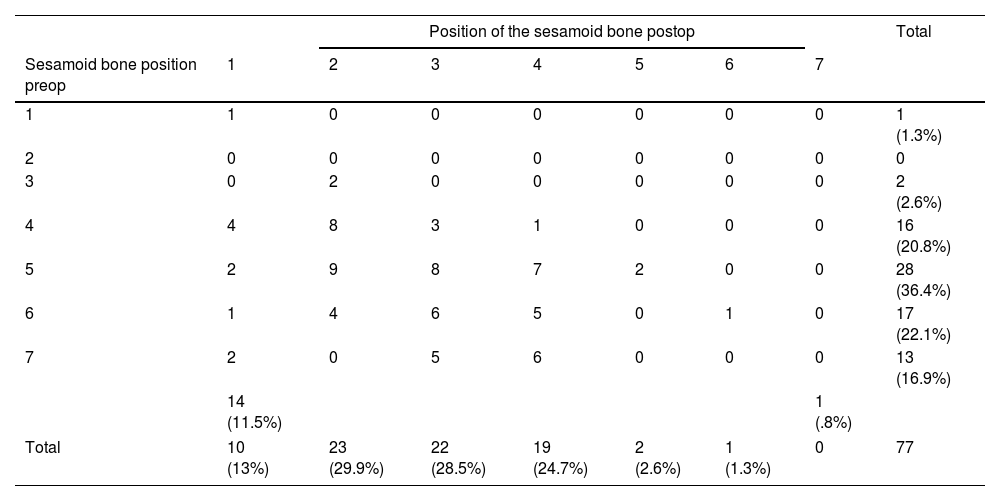

Tables 3 and 4 present the contingency tables for these variables, showing the changes in frequencies for each preoperative and postoperative group.

Contingency of the variable position of the sesamoid bone pre and postop (N=77).

| Position of the sesamoid bone postop | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sesamoid bone position preop | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.3%) |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.6%) |

| 4 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 (20.8%) |

| 5 | 2 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 28 (36.4%) |

| 6 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 17 (22.1%) |

| 7 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 (16.9%) |

| 14 (11.5%) | 1 (.8%) | |||||||

| Total | 10 (13%) | 23 (29.9%) | 22 (28.5%) | 19 (24.7%) | 2 (2.6%) | 1 (1.3%) | 0 | 77 |

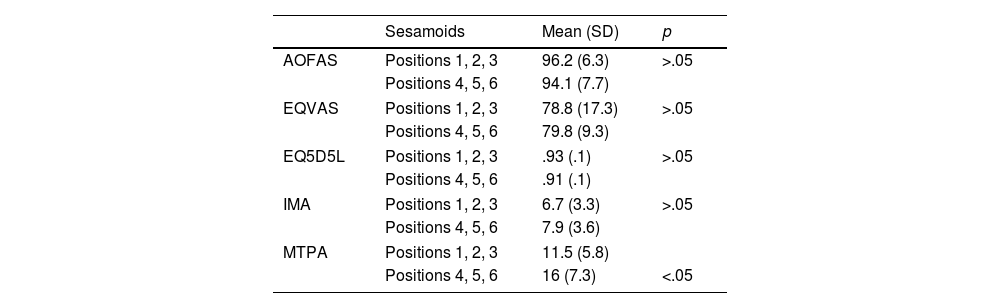

Similarly, the IMA, MTPA, AOFAS, EQVAS, and EQ5D5L variables were compared between Hardy and Clapham's sesamoid positions 1, 2 and 3 (n=55) and positions 4, 5 and 6 (n=22) at the end of the study (no patients were in position 7). The non-parametric Wilcoxon test was used for the comparison. The results are shown in Table 5.

Wilcoxon non-parametric test of sesamoid positions 1, 2, 3 with 4, 5, 6.

| Sesamoids | Mean (SD) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AOFAS | Positions 1, 2, 3 | 96.2 (6.3) | >.05 |

| Positions 4, 5, 6 | 94.1 (7.7) | ||

| EQVAS | Positions 1, 2, 3 | 78.8 (17.3) | >.05 |

| Positions 4, 5, 6 | 79.8 (9.3) | ||

| EQ5D5L | Positions 1, 2, 3 | .93 (.1) | >.05 |

| Positions 4, 5, 6 | .91 (.1) | ||

| IMA | Positions 1, 2, 3 | 6.7 (3.3) | >.05 |

| Positions 4, 5, 6 | 7.9 (3.6) | ||

| MTPA | Positions 1, 2, 3 | 11.5 (5.8) | |

| Positions 4, 5, 6 | 16 (7.3) | <.05 | |

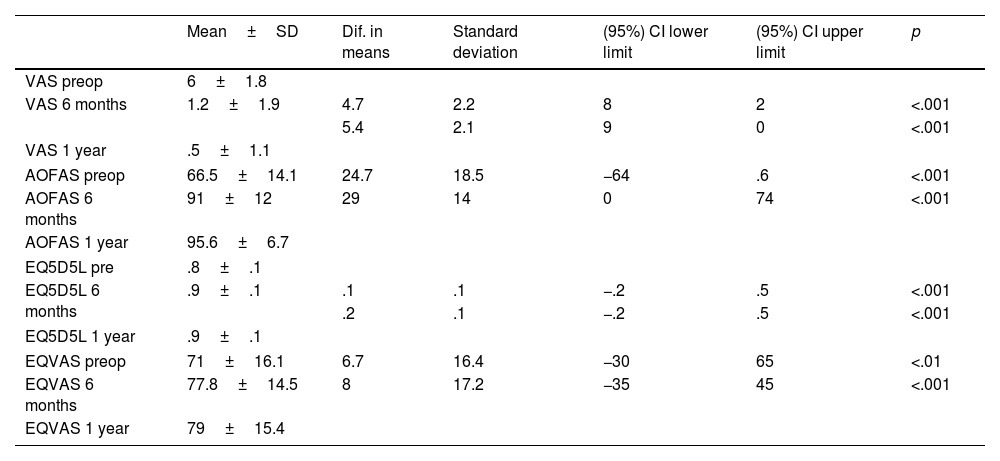

Table 6 shows the clinical results of the PROMs (VAS, AOFAS hallux MTF-IF, EQ5D5L, and EQVAS), illustrating a progressive increase in the mean score as follow-up progressed, reaching scores close to the maximum. This increase in score is statistically significant at both 6 months and 1 year of follow-up compared to the preoperative period (Table 6).

Wilcoxon test for paired samples of qualitative variables (N=77).

| Mean±SD | Dif. in means | Standard deviation | (95%) CI lower limit | (95%) CI upper limit | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS preop | 6±1.8 | |||||

| VAS 6 months | 1.2±1.9 | 4.7 | 2.2 | 8 | 2 | <.001 |

| 5.4 | 2.1 | 9 | 0 | <.001 | ||

| VAS 1 year | .5±1.1 | |||||

| AOFAS preop | 66.5±14.1 | 24.7 | 18.5 | −64 | .6 | <.001 |

| AOFAS 6 months | 91±12 | 29 | 14 | 0 | 74 | <.001 |

| AOFAS 1 year | 95.6±6.7 | |||||

| EQ5D5L pre | .8±.1 | |||||

| EQ5D5L 6 months | .9±.1 | .1 | .1 | −.2 | .5 | <.001 |

| .2 | .1 | −.2 | .5 | <.001 | ||

| EQ5D5L 1 year | .9±.1 | |||||

| EQVAS preop | 71±16.1 | 6.7 | 16.4 | −30 | 65 | <.01 |

| EQVAS 6 months | 77.8±14.5 | 8 | 17.2 | −35 | 45 | <.001 |

| EQVAS 1 year | 79±15.4 | |||||

The results of the intraclass correlation (ICC) reliability analysis for the IMA and MTPA variables were (using ICC) .93 and .98 for interobserver agreement and .95 and .97 for intraobserver agreement. The results of Cohen's kappa for the sesamoid position and first MTT pronation variables were .34 and .56 for interobserver agreement and .67 and .76 for intraobserver agreement.

According to the Clavien–Dindo–Sink classification adapted for hallux valgus surgery, there were 14 clinical complications reported (a rate of 18.18%):

Grade 1 (adverse effects that do not alter postoperative follow-up): one case of superficial infection with suture dehiscence that was treated with oral antibiotics. This represents 1.3%.

Grade 2 (complications that do not require surgery or additional hospitalisation): 2 cases of poor sagittal correction that required the use of insoles due to the development of metatarsalgia, 2 cases of mild bunion intolerance, 2 cases of nerve irritation, 2 cases of implant breakage with secondary sagittal misalignment, and 3 cases of asymptomatic recurrence of the deformity. This represents a total of 11 cases, or 14.3%.

Grade 3 (complications requiring surgery or hospitalisation): one case of deep infection requiring debridement surgery and one case of bone step intolerance requiring percutaneous filing. This represents 2.6%.

Although hallux valgus has traditionally been treated based on IMA and MTPA, it is now increasingly accepted1,2 that hallux valgus must be assessed and understood in three dimensions in order to improve surgical correction. This concept has been adopted in open surgery techniques21–23 but has not yet been tested in MIS techniques. This study analyses the corrective potential of pronation and the position of the sesamoid bones using MIS surgeries such as META in hallux valgus deformity. To this end, a technical modification was introduced for the correction of the deformity in the frontal plane, as described in this article.

The results obtained in this study show that the META technique with the modification described above has the capacity to correct hallux valgus deformity in the coronal and frontal planes, as assessed by the changes obtained in the AP weight-bearing X-ray. The mean IMA correction was 6.71°±3.83° (Table 2). We consider this to be a significant correction, especially given that the osteotomy performed is distal (a priori with less corrective capacity than diaphyseal or proximal osteotomies). A systematic review of angle correction in open hallux valgus surgery reported a mean correction of 5.33° (95% CI 5.12° to 5.54°) for Chevron osteotomy (n=1028) and 6.21° (95% CI 5.70° to 6.72°) for Scarf osteotomy (n=300).24 The results obtained in the present study in relation to this angle are slightly higher than those reported in these studies.

Similarly, the degree of MTPA correction obtained was 22.37°±9.37° (Table 2), which also represents a significant correction of the deformity. In this series of cases, all patients underwent the Akin technique, so it is possible that this influenced the degree of MTPA correction. We recognise that, in percutaneous techniques, MTPA correction through medial soft tissue retensioning has a lesser impact than performing the Akin osteotomy. However, the authors believe that part of the MTPA correction is also due to decreased soft tissue tension resulting from metatarsal shortening via metaphyseal osteotomy, as well as lateral soft tissue release. In the present study, all patients underwent both percutaneous techniques (metatarsal and proximal phalanx osteotomy) together with lateral soft tissue release. This makes it impossible to discern which of these manoeuvres plays a more significant role in correcting the MTPA.

The results of MTPA and MIA correction are consistent with those of other published studies in which a similar percutaneous surgical technique was employed. In a prospective randomised study. Lee et al.25 show a significant improvement in MTPA (from 31° to 8°) and IMA (from 16° to 6°) in the MIS group compared to the preoperative situation. More recently, Lewis et al. analysed 292 cases of hallux valgus treated with the MICA technique, achieving similar results after a 2-year follow-up (MTPA from 32.9 to 8.7 and IMA from 15.3 to 5.7).19

The same author reports good results with severe hallux valgus (HVA>40°, IMA>20°) with a 3-year follow-up (correction of HVA from 44.1° to 11.5° and IMA from 17.5° to 5.1°).26 In the authors’ opinion, the META technique described could also be indicated in severe hallux valgus, unless there is sagittal instability in the TMT or advanced osteoarthritis in the first MTP joint. Stability in the coronal plane appears to improve with the MICA technique, fixing the TMT joint in a maximum medial position.27

To date, few studies have measured the ability to correct pronation of the first metatarsal using percutaneous techniques. This study attempted to assess this correction by using AP projection under load to estimate the degree of pronation by analysing the shape of the lateral area of the metatarsal head based on Wagner's classification.14 This radiological assessment has been shown to be a valid method with high intra- and inter-observer reliability for estimating the degree of pronation of the first MTT28 and is an alternative for assessing the degree of pronation of the first MTT on the AP weight-bearing X-ray.29 In the present study, moderate and weak inter- and intra-observer agreement was obtained using this method, respectively, using Cohen's Kappa analysis of 20 cases. Furthermore, other authors have shown that the axial projection of the sesamoid is a test with poor reproducibility and reliability.30

In the present study, the META technique, modified for correction in the frontal plane, has demonstrated its ability to correct this parameter. Quantitative analysis of this variable revealed a mean correction of metatarsal head pronation (according to Wagner's classification) of 1.31°±.95° (Table 2). Qualitative analysis using the McNemar–Bowker test for repeated samples revealed significant changes in the pre- and post-frequencies of the four groups of patients who underwent surgery. Table 4 shows the preoperative and postoperative frequency changes obtained: 15 cases (83.3%) out of a total of 18 cases in preoperative group 1 moved to postoperative group 0; 13 cases (44.8%) out of a total of 29 cases in preoperative group 2 moved to postoperative group 0; and 10 cases (41.6%) out of a total of 24 cases in preoperative group 3 moved to postoperative group 0.

Similarly, this study has shown that this 4th generation MIS technique corrects the position of the sesamoid bones on AP X-rays. Quantitative analysis of this variable yielded a correction (according to the Hardy and Clapham classification) of 2.47±1.28 positions (Table 2). Qualitative analysis using the McNemar–Bowker test for repeated measures found significant changes in the pre and postoperative frequencies of the patients. Table 3 shows these frequency changes.

This clear improvement in the position of the sesamoids could be related to the ability of straight osteotomy to correct the head of the first MTT in all planes. Palmanovich et al.31 showed significant differences in the position of the sesamoids between straight osteotomies and V-shaped Chevron osteotomies (open or percutaneous) for the correction of hallux valgus. They associated these results with the ability of straight osteotomy to correct all planes of the deformity. This point seems to indicate the superiority of 4th generation techniques over 3rd generation techniques, although further studies are needed to corroborate this.

It is important to note that, according to Kim and Young,6 up to 26% of patients with hallux valgus could have an image of sesamoid subluxation as a result of metatarsal pronation. Therefore, part of the correction obtained in the position of the sesamoids on the AP X-ray could be due to correction of the deformity in the frontal plane. The weight-bearing axial projection of the sesamoids provides an excellent view of their position in relation to the first MTT, which can help differentiate between actual and pseudo-subluxation caused by pronation of the MTT.2 Nevertheless, some authors consider this projection to be poorly reproducible.2,14 Even authors who advocate the use of this projection describe limitations in cases of severe hallux valgus, such as erosion of the intersesamoid crest of the M1 head, or variations in the position of the sesamoids when the toe is placed in dorsiflexion due to increased tension in the flexor digitorum brevis.32 This led us to doubt the validity of the results obtained using this projection. Although this projection was taken in all cases, it was ultimately rejected for the purposes of this study.

Despite this statistically significant improvement in the position of the sesamoids on the AP X-ray, in the most severe degrees of sesamoid dislocation (positions 6 and 7), reduction (positions 1 and 2) was only achieved in 23% of cases. However, in milder dislocations (positions 3 and 4) (Table 3), optimal correction was achieved in 77% of cases. These results highlight the difficulty of correcting the position of the sesamoids in the most severe cases in the study, although, in the authors’ opinion, this occurs regardless of the technique used (open or closed). However, the position of the sesamoids does not seem to be reflected in the clinical results. Patients with the worst sesamoid positioning at one year of follow-up (positions 4, 5, and 6) had a mean AOFAS score of 94, slightly lower than the mean for the group with the best sesamoid positioning (positions 1, 2, 3) (96.2). The mean EQVAS and EQ5D5L scores at one year for patients with the worst sesamoid position are practically the same as those for patients with the best sesamoid position (79.7 and .91 versus 78.7 and .93, respectively), in all cases without statistical significance (Table 5). This is the same conclusion reached by a recent study that found no relationship between poor sesamoid position and clinical outcomes at one year of follow-up using a 4th generation technique.33 However, this same article links poor sesamoid position with poorer correction of the deformity, and this association is repeated in our study. Patients with positions 4, 5, and 6 in the Hardy and Clapham classification had higher IMA and MTPA values at one year of follow-up (7.90 and 14.6, respectively) compared to patients with positions 1, 2, and 3 (6.7 and 11.6), with a statistically significant difference in MTPA (p<.05). These results are consistent with the conclusions of several studies that identify sesamoid position as a factor in the recurrence of deformity and patient dissatisfaction in the postoperative period.34,35

In the present study, the authors intended to perform a percutaneous section of the adductor tendon of the first toe as a form of lateral release, in order to weaken the forces that maintain the deformity without releasing any structures inserted in the lateral sesamoid. However, based on the results obtained, this procedure, supported by the literature,36 may be insufficient in cases of chronic and severe sesamoid dislocation. A more extensive and aggressive lateral release may be required, including other structures in addition to the adductor tendon, such as the metatarsal sesamoid ligament (or suspensory ligament), the insertions of the lateral sesamoid, the lateral head of the flexor digitorum brevis, and the intermetatarsal ligament to improve the correction of the position of the sesamoids, as described by Winson and Perera.37 Once again, the authors emphasise the importance of correctly positioning the sesamoids to minimise the risk of recurrence and patient dissatisfaction during the postoperative period.34,35 Future studies are needed on the effect of extended lateral release as an adjunctive procedure in minimally invasive techniques in cases of severe sesamoid dislocation.

In our study, functional scale scores improved significantly following hallux valgus correction using 4th generation percutaneous surgery. This is consistent with the findings of other published studies.17,38 The AOFAS scale, the most widely used to rate clinical outcomes, improved from a mean preoperative value of 66.52±14.11 to 95.57±6.75 at the one-year follow-up. The same trend was observed for the VAS, with an average preoperative score of 5.96 and an average postoperative score of .54. Both differences were statistically significant (p<.001) (Table 6). The EuroQol showed a positive evolution in quality of life, as reflected in both the EQ5D5L index score (improving from .76±.16 preoperatively to .92±.11 at the one-year follow-up) and the EQVAS (improving from 71.06±16.15 preoperatively to 79.04±15.38 at the one-year follow-up), which were statistically significant (Table 6). These results suggest high patient satisfaction.

In our series, we recorded complications in a total of 14 cases (rate of 18.18%), of which 2 (2.60%) required some type of reoperation. This reoperation rate is slightly lower than other studies on the MICA technique, such as that by Lewis et al.,19 which reports a rate of 7.8%, but with a postoperative follow-up period that is twice as long as that of the present study. Therefore, complications such as recurrence of deformity may be detected to a greater extent in a longer follow-up period. It should be noted that 6 of the 14 complications recorded (42.85%) occurred in the first 30 cases, which may be related to the learning curve. Other authors also associate a higher complication rate during the early learning curve and estimate that between 20 and 50 cases must be performed to reach technical proficiency.19

The study has several limitations, so the results should be interpreted with caution. Firstly, this is a case series study and not a clinical trial with a control group, so we cannot guarantee that the correction obtained in the frontal plane is due exclusively to the technical modification performed, rather than to other factors such as the longitudinal decompression of deforming forces, shortening, or the correction of sesamoid position, and/or lateral release. Despite this limitation, however, the study has significant external validity as a case series, meaning its results are highly applicable to routine clinical practice, where clinicians and patients ultimately decide which surgical technique to use. Secondly, the study's reliability analysis showed almost perfect agreement for the IMA and HVA variables, for both inter- and intra-evaluator assessments. For the first MTT pronation variable, inter-observer agreement was weak and intra-observer moderate, which is lower than that reported by Wagner et al.28 The position of the sesamoid bone produced somewhat lower results, with minimal inter-observer agreement and moderate intra-observer agreement. While the results for the first three variables appear valid based on the reliability analysis, the reliability results for the sesamoid bone position may affect the results and conclusions reported in this study with respect to that variable. Thirdly, pronation correction of the first metatarsal was estimated using AP X-rays with the aforementioned Wagner and Wagner's classification.14 As we have already mentioned, this classification has proven valid and reliable. It estimates the degree of metatarsal rotation and classifies it into 4 ordinal groups. However, it does not allow the degrees of deformity to accurately quantified (as a quantitative variable). Therefore, although the results obtained have shown that the technique corrects this deformity in the frontal plane, we cannot determine the exact degree of correction achieved. In order to accurately determine the pre and postoperative deformity, a weight-bearing CT scan would be necessary. Unfortunately, however, the authors did not have access to this test in their setting, meaning it could not be performed. Thirdly, the follow-up period in this study was relatively short (12 months), which may be insufficient to assess the long-term efficacy of the technique, the incidence of possible future recurrences and the clinical results. Finally, the AOFAS hallux MTF-IF questionnaire was used for clinical assessment. However, the MOXFQ is a more specific PROM for patients undergoing foot surgery and has been validated for assessing those who have undergone hallux valgus surgery.16,26

ConclusionsThis study has demonstrated that the proposed 4th generation minimally invasive technique can be used to correct hallux valgus deformity in three planes, with a relatively low reoperation rate. Statistically significant corrections were obtained for MTPA, IMA, sesamoid position, and first metatarsal pronation in the frontal plane as measured on AP X-rays. However, analysis of sesamoid position yielded moderate to low reliability. Further research is needed to evaluate the potential of frontal plane correction using minimally invasive techniques in patients with hallux abducto valgus, as well as the long-term effects of this treatment.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence ii.

AuthorshipAll of the authors listed on this manuscript have seen and approved its submission and accept full responsibility for it.

Contribution to the studyRaul Torre Puente: study conception and design, surgical treatment, article draft, final approval of the article.

Mauri Rotinen: surgical treatment, collection of data from medical records, final approval of the article.

Lara Fernandez Gutierrez: measurement of radiographic parameters.

Arkaitz Lara Quintana: obtaining data from medical records, final approval of the article.

Julia Isabel Martino Quintela: obtaining data from medical records, final approval of the article.

Javier Pascual Huerta: evaluated results, critical review of intellectual content, methodology, and statistical analysis.

Informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data violate patient privacy and confidentiality, nor allow for patient identification. All participants signed a written consent form to participate in the research and to allow the presentation of the results in a publication.

FundingThis research study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We would like to thank Dr. Daniel Escobar for his help in editing the images and Amaia Bilbao for her help in the statistical analysis.