Accounting information on social benefits is included, in accordance with the scope of its management, in the general Social Security budget. The information contained in the budget may be relevant, but it is likely to be insufficient to enable comparisons to be made with an entity's financial statements for previous periods and with the financial statements of other entities. Thus, IPSAS 1 proposes the presentation of additional information. On the basis of the New Public Management theory, this paper proposes an aggregate accounting model for accounting expenditure as a multi-annual information system which complements and expands information on a potential basic social benefit. This system reports in detail on the trends in the items that fund it, with the aim of achieving maximum transparency and accountability in public administrations by ensuring timely provision of quality information.

La información contable sobre prestaciones sociales se incluye, de acuerdo con el ámbito de su gestión, en el presupuesto general de la Seguridad Social. La información que contiene el presupuesto puede ser relevante, pero es probable que sea insuficiente para permitir comparaciones con los estados financieros de una entidad de períodos anteriores y con los estados financieros de otras entidades. Por tanto, IPSAS 1 propone la presentación de información adicional. Sobre la base de la teoría de la «Nueva Gestión Pública», este documento propone un modelo de contabilidad agregado para el gasto contable como un sistema de información plurianual que complementa y amplía la información sobre una posible prestación social básica. Este sistema informa detalladamente sobre las tendencias de los temas que la financian con el objetivo de lograr la máxima transparencia y responsabilidad en las administraciones públicas para asegurar la provisión oportuna de información de calidad.

Together with the necessity of cover for basic needs, remedying the lack of transparency and accountability in the management of social aid has become a common aim all over the world. Thus, we propose a possible basic social assistance benefit (BSAB), which is a universal pension able to cover the minimum survival needs of citizens. It is based on the idea of Basic Income, a universal, unconditional, individual aid that involves giving the same amount of money to each citizen. However, BSAB is calculated taking on board expenditure on basic needs rather than a citizen's income. Moreover, it is not unconditional because it considers the synergies of living together and the fact that citizens may share some basic expenditures (Peña-Miguel, De La Peña, & Fernández-Sainz, 2015). The aid proposed would be supported by the public sector and more precisely by the social security system. The funds to support it could be raised from Social Security by slightly increasing the percentage of contributions made by employers and employees and from current state contributions (Peña-Miguel & De La Peña, 2017).

To reduce the lack of transparency and accountability and take on board the cost of such aid the right management tool needs to be created. We propose an information system that would report in detail on trends in the items that fund it, with the aim of achieving maximum transparency in accountability. Moreover, citizens demand more financial information from the public sector, including details of its performance on economic, social and environmental issues. In fact, they demand efficiency in the allocation and use of public resources and transparency in management for the sake of accountability. Thus, maximum transparency needs to be attained in accountability for basic social assistance benefit.

The aim of this paper is to offer a multi-annual information system that complements and expands information on a possible basic social assistant benefit (BSAB). It can help to achieve the desired levels of transparency and accountability. This system is based on the Conceptual Framework for General Purpose Financial Reporting by Public Sector Entities.

Indeed, IPSAS 1 proposes that financial statements should show information to ensure comparability both with an entity's financial statements from previous periods and the financial statements of other entities. To that end, in our system financial statements are prepared on an accrual basis, providing information about past transactions and other events but making forecasts for the future which are updated when events occur and not only when cash or its equivalent is received or paid.

Management accounting already uses some instruments which build information systems that are used for annual budget management, and this information must be shown to stakeholders. Moreover, refinement is required because it not only has to be limited to a particular economic period but must also take into account the economic situation and economic policy objectives in the long term. Dillard and Roslender (2011) proposes heteroglossic accounting as a way of addressing the different perspectives and information needs of alternative constituencies. Thus, we propose a multi-year framework for funding the BSAB budget in the long term. Otherwise, the BSAB proposed may not be sustainable due to the lack of funding and will fail to fulfil its intended purpose.

There are various models that can be used to search for this multi-annual information system (generational accounting, aggregate accounting, microsimulation, etc.) but aggregate accounting stands out. Aggregate accounting models make it possible to give sufficient information, at the desired level of disaggregation, up to where one stands with expenditure and where income comes from. Their design means that they can be projected long enough into the future to avoid the influence of politics on public management.

This paper makes two important contributions. First, it shows a novel application for a hypothetical, uniform social benefit for all Spanish citizens, where social contributions are raised to deal with a benefit that focuses on the needs of all citizens by keeping the commitments of the various administrations on financing (local, regional and state). At income level, different revenue sources are taken into account, taking at least those which existed in 2010. The application of funds is initially been broken down into levels by type, i.e. active, retired, unemployed and other beneficiaries. The second contribution is that the model has been created using an accrual criterion instead of the cash criterion currently used in budgets and public accounting. This means that it takes on board the commitments needed and the obligations accrued.

The article is structured as follows: Section Two highlights the influence and importance of the theory of New Public Management (NPM) and New Public Financial Management (NPFM), which seek accountability and transparency, as a basis for creating an aggregate accounting model that helps to improve the management of public assets and services. Section Three analyses the conceptual framework and the budgetary principles of financial information and the legislation that regulates accounting information in Spain, as Spanish legislation has adapted to international demands on emitting budgetary principles for financial reporting by public bodies. Section Four sets out the accounting information model, based on the needs set by NPM, NPFM and IPSAS 1 and existing accounting regulations. The paper ends with an outline of the contributions made and the limitations of the model, some conclusions and a list of bibliographical references.

The aim of this paper is to offer a multi-annual information system that complements and expands information on a possible basic social benefit. This system would report in detail on the trends in the items that fund it, with the aim of achieving maximum transparency in accountability.

Theoretical frameworkTransparency is defined as the availability of information to the public and clarity on government rules, regulations and decisions (Hood, 2006; Kondo, 2002). Transparency is also defined as reliable, relevant, and timely information about the activities of government (Kondo, 2002). Interest in transparency is increasing worldwide (Albalate, 2013). All countries have been required by the World Bank to implement specific projects to enhance transparency in order to reduce the number of cases of corruption. However, there are still some problems with the information provided to the public, such as availability, reliability and timeliness.

Government transparency is increasing worldwide and political rhetoric assumes a strong positive link between transparency and accountability (Meijer, 2014). The word ‘accountability’ is often used when considering fair and equitable governance (Bovens, 2005). With regard to the public sector, various types are normally mentioned by researchers (Bovens, 2005; Day & Klein, 1987; Romzek & Dubnick, 1987; Sinclair, 1995; Stewart, 1984), such as public, political, managerial or administrative, organisational, professional and personal accountability. Moreover, some types can be classified into sub-types.

In the private sector, managerial accountability can be classified as fiscal/regularity accountability, process/efficiency accountability and programme/effectiveness accountability (Day & Klein, 1987). In the public sector there is evidence of the impact of New Public Management (NMP) reforms in enhancing public accountability. Drawing on the paper by Broadbent and Guthrie (1992), Hassan (2015) posits that, under the umbrella of NPM, public sector bodies have transformed their financial statements to incorporate accrual accounting principles, in what is broadly regarded as an attempt to improve transparency and accountability. Thus, public financial statements are based on the Theory of New Public Management and New Public Financial Management on the basis that transparency and expenditure control enhance the information and timely submission of financial statements.

The new philosophy of public management is “a marriage between New Institutionalism and professional management” (Hood, 1991). New Institutionalism considers that public institutions are relevant in understanding and explaining the interactions between individuals, as they are equipped with their own logic which conditions individual preferences (Lapsley & Oldfield, 2001). Professional management, defined primarily from the ideas of the neo-Taylorists (Pollitt, 1993), focuses on studying the internal bureaucratic organisation of the administration, advocating the shattering of the myth of differences in management between the private and the public sectors (Arellano, 2002).

Public Financial Management (PFM) is defined as a set of activities related to budget preparation, implementation, control, accounting, reporting, monitoring and evaluation (Allen, Schiavo-Campo, & Garrity, 2004). New Public Financial Management looks to prescribe measures to ensure transparency and expenditure control in all spheres of government, and to set operational procedures for borrowing, guarantees, procurement and oversight over the various national and provincial revenue funds. It looks to improve information and the timely submission of financial statements.

In all the theories outlined above, the need to develop and refine monitoring tools, especially those for assessing achievements and results, is associated in the literature with new public management, with the introduction of concepts, practices and techniques from the private sector (Fernández Rodríguez, 2000) intended solely for controlling results (Boden, Gummett, Cox, & Barker, 1998; Broadbent & Laughlin, 1998), or is broadened to introduce improvements in management through deregulation, decentralisation and the introduction of competition and transparency in accountability (Coninck-Smith, 1991; Ladner,1999).

Conceptual frameworkThe primary objective of most public sector entities is to deliver services to the public, rather than to make profits and generate a return on equity for investors. The Conceptual Framework addresses key public sector characteristics in its approach to elements, the measurement of assets and liabilities and the presentation of financial reports, while focusing on the needs of service recipients and resource providers for high-quality financial reporting information for both accountability and decision-making purposes (International Public Sector Accounting Standards, 2013).

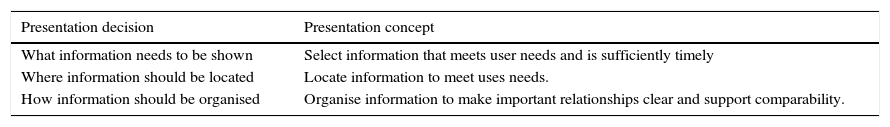

Fulfilling these financial information objectives, and thus meeting the needs of stakeholders, calls for additional information, including non-financial statements, in order to offer the most comprehensive, detailed description possible with the data available. This requires an additional information system where data, items and changes included can be expanded over time in order to show information accurately. IPSAS establishes three presentation concepts (Table 1) to guide presentation decisions for general purpose financial reports (GPFRs)

Presentation decisions and presentation concepts.

| Presentation decision | Presentation concept |

|---|---|

| What information needs to be shown | Select information that meets user needs and is sufficiently timely |

| Where information should be located | Locate information to meet uses needs. |

| How information should be organised | Organise information to make important relationships clear and support comparability. |

Source: IPSASB (2012).

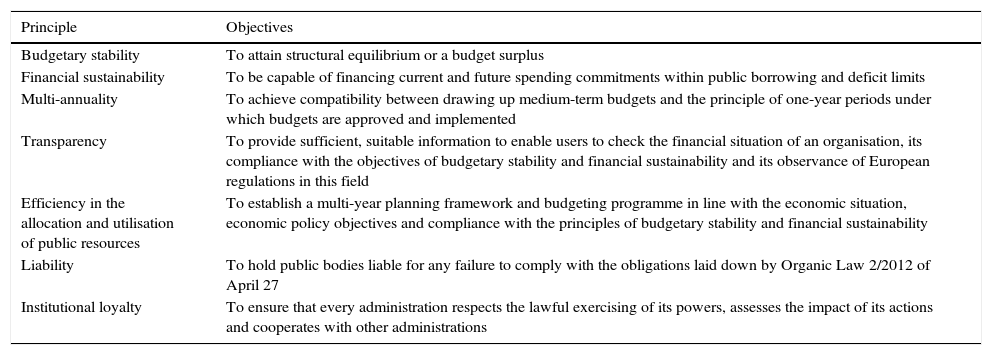

In tandem with many other continental European countries, there is a strong legalistic tradition in Spain, where the administrative law model is prevalent in the public sector. Central government is the key accounting regulator, with sole responsibility for determining standards for both businesses and the public sector through legislative means (Brusca, Montesinos, & Chow, 2013). Hence, in this context budgeting principles for financial information on public bodies must not be forgotten (see Table 2). “Public General Act 2/2012 of April 27 on Budgetary Stability and Financial Sustainability (”Ley Orgánica 2/2012, de 27 de abril, de Estabilidad Presupuestaria y Sostenibilidad Financiera“) on Budgetary Stability and Financial Sustainability sets out the general principles by which the public sector is to be governed. In this case “public sector” does not just mean central government and its dependent bodies but also the administrations of Spain's autonomous communitieslocal corporations, social security administrations and their dependent bodies, other publicly-run enterprises, mercantile companies and bodies covered by public law and answerable to public administrations (Spanish Official State Bulletin no. 103, dated 30/04/2012). In the case that concerns us here, the General Treasury of the Social Security System is the organisation charged with managing BSAB. It must follow the principles we summarise in Table 2.

Budgeting principles for financial information on public bodies.

| Principle | Objectives |

|---|---|

| Budgetary stability | To attain structural equilibrium or a budget surplus |

| Financial sustainability | To be capable of financing current and future spending commitments within public borrowing and deficit limits |

| Multi-annuality | To achieve compatibility between drawing up medium-term budgets and the principle of one-year periods under which budgets are approved and implemented |

| Transparency | To provide sufficient, suitable information to enable users to check the financial situation of an organisation, its compliance with the objectives of budgetary stability and financial sustainability and its observance of European regulations in this field |

| Efficiency in the allocation and utilisation of public resources | To establish a multi-year planning framework and budgeting programme in line with the economic situation, economic policy objectives and compliance with the principles of budgetary stability and financial sustainability |

| Liability | To hold public bodies liable for any failure to comply with the obligations laid down by Organic Law 2/2012 of April 27 |

| Institutional loyalty | To ensure that every administration respects the lawful exercising of its powers, assesses the impact of its actions and cooperates with other administrations |

Source: Organic Law 2/2012 of April 27 on Budgetary Stability and Financial Sustainability.

The aim of this paper is to propose an aggregate accounting model for accounting expenditure as a multi-annual information system which complements and expands information on a potential BSAB in Spain. Accordingly, the existing budgeting principles which support it are budgetary stability (the model proposed is based on an equilibrium between resources and benefits), multi-annuality (the model proposed is a multi-year information system intended to achieve a long term equilibrium and be financed in the long term (from 2010 to 2021)) and efficiency in the allocation and utilisation of public resources (the model proposed looks to make the best use of resources, using them with efficiency and effectiveness).

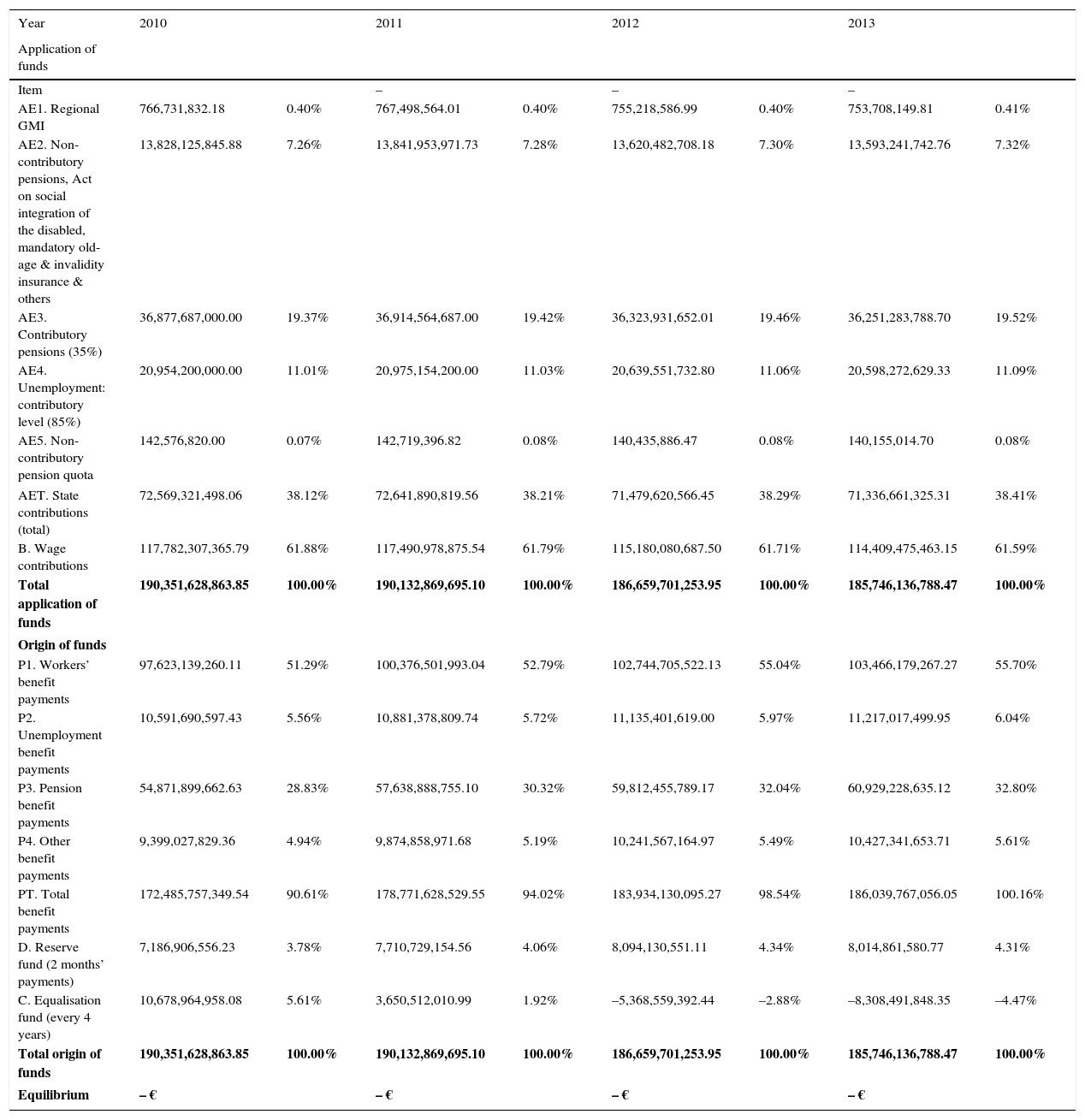

Peña-Miguel et al. (2015) define the BSAB as a financial assignation paid annually to each citizen that is sufficient to cater for their minimum requirements for survival in accordance with their age, town of residence, employment situation, number of dependents and region of residence (Autonomous Community in Spain). Using an inter-quartile regression model, they also find a quantitative relationship between the amount of total household spending devoted to basic necessities and the significant factors listed above, which are also the variables or factors used each year in the EPF and in earlier studies of the determinants of spending in Spain. By applying the quantitative factors obtained from the regression (Peña-Miguel et al., 2015) to the sample in the EPF for 2010, the aggregate amount of the benefit (see Table 3).

Basic social assistance benefit balance sheet for a 12-year period.

| Year | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Application of funds | ||||||||

| Item | – | – | – | |||||

| AE1. Regional GMI | 766,731,832.18 | 0.40% | 767,498,564.01 | 0.40% | 755,218,586.99 | 0.40% | 753,708,149.81 | 0.41% |

| AE2. Non-contributory pensions, Act on social integration of the disabled, mandatory old-age & invalidity insurance & others | 13,828,125,845.88 | 7.26% | 13,841,953,971.73 | 7.28% | 13,620,482,708.18 | 7.30% | 13,593,241,742.76 | 7.32% |

| AE3. Contributory pensions (35%) | 36,877,687,000.00 | 19.37% | 36,914,564,687.00 | 19.42% | 36,323,931,652.01 | 19.46% | 36,251,283,788.70 | 19.52% |

| AE4. Unemployment: contributory level (85%) | 20,954,200,000.00 | 11.01% | 20,975,154,200.00 | 11.03% | 20,639,551,732.80 | 11.06% | 20,598,272,629.33 | 11.09% |

| AE5. Non-contributory pension quota | 142,576,820.00 | 0.07% | 142,719,396.82 | 0.08% | 140,435,886.47 | 0.08% | 140,155,014.70 | 0.08% |

| AET. State contributions (total) | 72,569,321,498.06 | 38.12% | 72,641,890,819.56 | 38.21% | 71,479,620,566.45 | 38.29% | 71,336,661,325.31 | 38.41% |

| B. Wage contributions | 117,782,307,365.79 | 61.88% | 117,490,978,875.54 | 61.79% | 115,180,080,687.50 | 61.71% | 114,409,475,463.15 | 61.59% |

| Total application of funds | 190,351,628,863.85 | 100.00% | 190,132,869,695.10 | 100.00% | 186,659,701,253.95 | 100.00% | 185,746,136,788.47 | 100.00% |

| Origin of funds | ||||||||

| P1. Workers’ benefit payments | 97,623,139,260.11 | 51.29% | 100,376,501,993.04 | 52.79% | 102,744,705,522.13 | 55.04% | 103,466,179,267.27 | 55.70% |

| P2. Unemployment benefit payments | 10,591,690,597.43 | 5.56% | 10,881,378,809.74 | 5.72% | 11,135,401,619.00 | 5.97% | 11,217,017,499.95 | 6.04% |

| P3. Pension benefit payments | 54,871,899,662.63 | 28.83% | 57,638,888,755.10 | 30.32% | 59,812,455,789.17 | 32.04% | 60,929,228,635.12 | 32.80% |

| P4. Other benefit payments | 9,399,027,829.36 | 4.94% | 9,874,858,971.68 | 5.19% | 10,241,567,164.97 | 5.49% | 10,427,341,653.71 | 5.61% |

| PT. Total benefit payments | 172,485,757,349.54 | 90.61% | 178,771,628,529.55 | 94.02% | 183,934,130,095.27 | 98.54% | 186,039,767,056.05 | 100.16% |

| D. Reserve fund (2 months’ payments) | 7,186,906,556.23 | 3.78% | 7,710,729,154.56 | 4.06% | 8,094,130,551.11 | 4.34% | 8,014,861,580.77 | 4.31% |

| C. Equalisation fund (every 4 years) | 10,678,964,958.08 | 5.61% | 3,650,512,010.99 | 1.92% | –5,368,559,392.44 | –2.88% | –8,308,491,848.35 | –4.47% |

| Total origin of funds | 190,351,628,863.85 | 100.00% | 190,132,869,695.10 | 100.00% | 186,659,701,253.95 | 100.00% | 185,746,136,788.47 | 100.00% |

| Equilibrium | – € | – € | – € | – € | ||||

| Year | 2.014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Application of funds | ||||||||

| Item | – | – | – | – | ||||

| AE1. Regional GMI | 761,245,231.31 | 0.39% | 768,857,683.63 | 0.39% | 776,546,260.46 | 0.39% | 784,311,723.07 | 0.39% |

| AE2. Non-contributory pensions, Act on social integration of the disabled, mandatory old-age & invalidity insurance & others | 13,729,174,160.19 | 6.95% | 13,866,465,901.79 | 6.97% | 14,005,130,560.81 | 7.01% | 14,145,181,866.42 | 7.04% |

| AE3. Contributory pensions (35%) | 36,613,796,626.59 | 18.52% | 36,979,934,592.86 | 18.60% | 37,349,733,938.79 | 18.69% | 37,723,231,278.17 | 18.78% |

| AE4. Unemployment: contributory level (85%) | 20,804,255,355.63 | 10.53% | 21,012,297,909.18 | 10.57% | 21,222,420,888.28 | 10.62% | 21,434,645,097.16 | 10.67% |

| AE5. Non-contributory pension quota | 141,556,564.84 | 0.07% | 142,972,130.49 | 0.07% | 144,401,851.80 | 0.07% | 145,845,870.32 | 0.07% |

| AET. State contributions (total) | 72,050,027,938.57 | 36.45% | 72,770,528,217.95 | 36.60% | 73,498,233,500.13 | 36.77% | 74,233,215,835.13 | 36.96% |

| B. Wage contributions | 125,602,591,603.34 | 63.55% | 126,038,984,009.59 | 63.40% | 126,374,297,598.97 | 63.23% | 126,614,040,777.96 | 63.04% |

| Total application of funds | 197,652,619,541.90 | 100.00% | 198,809,512,227.54 | 100.00% | 199,872,531,099.10 | 100.00% | 200,847,256,613.09 | 100.00% |

| Origin of funds | ||||||||

| P1. Workers’ benefit payments | 105,800,461,816.29 | 53.53% | 108,118,192,504.74 | 54.38% | 110,403,696,629.01 | 55.24% | 112,652,167,226.85 | 56.09% |

| P2. Unemployment benefit payments | 11,480,062,489.09 | 5.81% | 11,749,279,151.75 | 5.91% | 12,022,694,811.00 | 6.02% | 12,303,467,260.28 | 6.13% |

| P3. Pension benefit payments | 62,917,089,923.95 | 31.83% | 65,076,625,915.63 | 32.73% | 67,065,085,150.94 | 33.55% | 68,957,241,895.62 | 34.33% |

| P4. Other benefit payments | 10,762,404,437.35 | 5.45% | 11,119,288,301.12 | 5.59% | 11,422,849,397.40 | 5.72% | 11,694,073,014.88 | 5.82% |

| PT. Total benefit payments | 190,960,018,666.68 | 96.61% | 196,063,385,873.24 | 98.62% | 200,914,325,988.36 | 100.52% | 205,606,949,397.62 | 102.37% |

| D. Reserve fund (2 months’ payments) | 820,041,935.11 | 0.41% | 850,561,201.09 | 0.43% | 808,490,019.19 | 0.40% | 782,103,901.54 | 0.39% |

| C. Equalisation fund (every 4 years) | 5,872,558,940.11 | 2.97% | 1,895,565,153.21 | 0.95% | –1,850,284,908.45 | –0.93% | –5,541,796,686.08 | –2.76% |

| Total origin of funds | 197,652,619,541.90 | 100.00% | 198,809,512,227.54 | 100.00% | 199,872,531,099.10 | 100.00% | 200,847,256,613.09 | 100.00% |

| Equilibrium | – € | – € | – € | – € | ||||

| Year | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Application of funds | ||||||||

| Item | – | – | – | – | ||||

| AE1. Regional GMI | 792,154,840.30 | 0.36% | 800,076,388.70 | 0.36% | 808,077,152.59 | 0.37% | 816,157,924.11 | 0.37% |

| AE2. Non-contributory pensions, Act on social integration of the disabled, mandatory old-age & invalidity insurance & others | 14,286,633,685.08 | 6.53% | 14,429,500,021.93 | 6.57% | 14,573,795,022.15 | 6.62% | 14,719,532,972.37 | 6.66% |

| AE3. Contributory pensions (35%) | 38,100,463,590.96 | 17.42% | 38,481,468,226.86 | 17.53% | 38,866,282,909.13 | 17.65% | 39,254,945,738.22 | 17.77% |

| AE4. Unemployment: contributory level (85%) | 21,648,991,548.13 | 9.90% | 21,865,481,463.61 | 9.96% | 22,084,136,278.25 | 10.03% | 22,304,977,641.03 | 10.09% |

| AE5. Non-contributory pension quota | 147,304,329.02 | 0.07% | 148,777,372.31 | 0.07% | 150,265,146.03 | 0.07% | 151,767,797.49 | 0.07% |

| AET. State contributions (total) | 74,975,547,993.48 | 34.29% | 75,725,303,473.42 | 34.50% | 76,482,556,508.15 | 34.72% | 77,247,382,073.23 | 34.96% |

| B. Wage contributions | 143,701,216,739.22 | 65.71% | 143,778,436,300.34 | 65.50% | 143,780,182,749.61 | 65.28% | 143,716,401,695.01 | 65.04% |

| Total application of funds | 218,676,764,732.70 | 100.00% | 219,503,739,773.76 | 100.00% | 220,262,739,257.76 | 100.00% | 220,963,783,768.25 | 100.00% |

| Origin of funds | ||||||||

| P1. Workers’ benefit payments | 114,840,163,477.52 | 52.52% | 116,966,878,644.60 | 53.29% | 119,016,042,619.24 | 54.03% | 120,979,502,088.09 | 54.75% |

| P2. Unemployment benefit payments | 12,583,637,860.21 | 5.75% | 12,861,363,883.73 | 5.86% | 13,134,153,765.34 | 5.96% | 13,403,161,553.02 | 6.07% |

| P3. Pension benefit payments | 70,892,923,905.75 | 32.42% | 73,904,183,164.00 | 33.67% | 76,495,235,405.17 | 34.73% | 79,742,653,768.22 | 36.09% |

| P4. Other benefit payments | 11,957,696,648.34 | 5.47% | 12,437,113,882.55 | 5.67% | 12,795,217,427.20 | 5.81% | 13,274,241,917.08 | 6.01% |

| PT. Total benefit payments | 210,274,421,891.82 | 96.16% | 216,169,539,574.89 | 98.48% | 221,440,649,216.96 | 100.53% | 227,399,559,326.41 | 102.91% |

| D. Reserve fund (2 months’ payments) | 777,912,082.37 | 0.36% | 982,519,613.84 | 0.45% | 878,518,273.68 | 0.40% | 993,151,684.91 | 0.45% |

| C. Equalisation fund (every 4 years) | 7,624,430,758.51 | 3.49% | 2,351,680,585.03 | 1.07% | –2,056,428,232.88 | –0.93% | –7,428,927,243.07 | –3.36% |

| Total origin of funds | 218,676,764,732.70 | 100.00% | 219,503,739,773.76 | 100.00% | 220,262,739,257.76 | 100.00% | 220,963,783,768.25 | 100.00% |

| Equilibrium | – € | – € | – € | – € | ||||

Source: own work.

Thus, given the particular characteristics of basic social assistance benefit, the information system for it requires three special characteristics or principles which are at the heart of the reasons and need for this BSAB. They are innate in BSAB, which is inconceivable without them. Universality, citizen orientation and social/inter-regional justice and equity are inputs without which the output (BSAB) cannot be reached.

Universality is required to meet the information requirements of all users and to offer information on the matter under study, describing the concepts and forecasts made in monetary and non-monetary terms in order to provide useful, reliable, accurate information on the management of the benefit in question.

Citizen orientation is required to work to a code of practice based on transparency, in tune with the community (Cubillo, 2002) and budgetary rationality (Peña-Miguel, De La Peña, & Fernández, 2012).

Social/inter-regional justice and equity to promote inter-generational solidarity (Commission of the European Communities, 2007) through nationwide family policies, to work for transparency in accountability for the efficient use of resources and budgetary rationality as a socially responsible objective and to take any actions necessary so that intra-and inter-generational equity is sustainable (Peña-Miguel et al., 2012).

The inter-generational solidarity, which currently exists in the Spanish social security system, must be considered as part of the Spanish heritage. In addition, the current inter-regional solidarity in contributions to the sustainability of the income and tax system is highly important in understanding the level of welfare in Spain. These values are the heritage of Spanish culture and must be continued, otherwise the existence of BSAB will be at risk.

Financial and accounting information modelThe NPM and NPFM theories and International Public Sector Accounting Standards point to a need to develop and refine viable tools aimed at assessing achievements and sustainable results. To that end we propose an aggregate accounting model to offer a multi-annual information system that complements and expands information on a possible basic social benefit. This model will be suitable for evaluating the performance of each entity in terms of service costs, efficiency and accomplishments. In addition, accurate information should be provided on funding sources, allocation and use of financial resources, so we break down the items comprising the source and application of funds.

It is necessary for the government to be held accountable for its actions, in terms of costs and management (Canales, 2012). An effective management accounting system must be set up as a tool for improving the management of public organisations, similar in content to the systems in place for the business sector (Brusca, 1997). But given the public nature of the bodies involved, internal information should not be considered alone but rather together with the external information disclosed by public administrations (Brusca, 2013).

That is why we propose a system of additional information here that complements the information provided in financial statements, in the form of a balance sheet where items are valued by fixed projections based on verifiable facts at the effective date of the balance sheet.

The tools available to governments for analysing/simulating the economic effects of their decisions include the following:

- a)

Accounting calculations or aggregate accounting models for expenditure based on the legislation in force in each country and on the statistical information available. These models may include high levels of detail and heterogeneity, and may be similar to micro-simulation models with no predefined behaviour.

- b)

General dynamic equilibrium models based on a general equilibrium approach that incorporates the relationships between economic and demographic variables into the model using dynamic formulae (Shantayanan & Delfin, 1998).

- c)

Dynamic micro-simulation population models based on population micro-data with maximum heterogeneity. These enable different characteristics of individuals to be identified over time (Klevmarken, 2008).

- d)

Generational accounting models intended to assess the sustainability of long-term public sector policies as a whole, where the demographic factor (population ageing) is particularly significant (Auerbach, Gokhale, & Kotlikoff, 1994).

Of the 4 models listed above, we decided to use the aggregate accounting model (AAM) for expenditure, as we believe it to be the one that best fits the financial information system for BSAB studied here. Moreover, it is a model that is used by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the European Union's Working Group on Ageing Populations and Sustainability (AWG). General dynamic equilibrium models provide a framework in which sets of assumptions can be easily understood and compared. However, for the model to be complete a sound theory for forming expectations is needed (Kehoe, 1987), and such a model has no place in this study because of the concept of basic necessity that underlies BSAB.

Dynamic micro-simulation models use IT applications that establish a structure of taxation and benefits operating on economic units at micro level, particularly households and individuals. Simulations produced under such models could be used to estimate the repercussions of the distribution of income, levels of inequality and poverty and, more generally, the social welfare that would result from changes in policy in a particular period.

However that is not the objective pursued here, so the use of such models is not considered feasible. The benefit studied here is intended to cover the basic needs of all citizens, not to analyse whether levels of inequality and poverty improve: this can be taken as given in view of the idea of redistribution that by definition underlies BSAB (Peña-Miguel et al., 2015).

Generational accounting models are based on inter-temporal budget constraints in the public sector. In the case studied here there are no such constraints, given that the benefit in question is to be funded mainly from contributions that are already being made, forecasts for which are drawn up using different potential scenarios (Peña-Miguel et al., 2015).

The AAM is a model that enables forecasts for the future to be drawn up based on 5 hypothetical scenarios. Once the amount to which each individual in the Spanish population is entitled in a given year (for the purposes of the study the year considered is 2010). In addition, he relevant funding possibilities have been determined, resulting in clear, reliable financial and accounting information by means of which it is possible to determine the origins and applications of the resources needed to fund basic social assistance benefit. The model is drawn up on the basis of the methodological framework applied by the AWG and the OECD.

Previous experiencesThe models used in previous experiences seek to provide useful information following the aims of the NPM and NPFM theories. Taking demographic, economic and financial variables into account, they show the measurement of assets and liabilities and the presentation of financial reports.

AAMs involve a financial/actuarial approach, as they are based on the determination of a succession of treasury statuses, rather than stressing the commitments undertaken by the system. They are widely used by public administrations and official bodies, e.g. by the Ageing Working Group and by the technical working group of the EU's Economic Policy Committee responsible for expenditure forecasts. The World Bank uses a different model based on aggregate accounting, known as PROST (Pension Reform Options Simulation Toolkit), and the ILO (International Labour Organization) also has its own aggregate model known as the ILO Pension Model. Out of all these models we took PROST as our basis for the following reasons:

PROST was designed to estimate future trends in the pension system over a long time frame (coverage, financial flows, adequacy of benefits, equity). It is also used to test the robustness of the system to shocks (demographic and economic). PROST enables the pension system to be considered as a whole as well as at the individual level. It addresses all policy dimensions. It can easily take on board different country circumstances. It is able to model national, closed-group, multiple (fragmented) schemes modelling reforms relatively fast and easily.

The model utilises country-specific data provided by the user. It generates population projections which are used in combination with economic assumptions to forecast future numbers of contributors and beneficiaries. These in turn generate flows of revenues and expenditures. The model then projects fiscal balances, taking account of any partial pre-funding of liabilities.

The model can assess anything from ‘parametric’ reforms of initial pay-as-you-go systems—changing pensionable ages, contribution rates, benefits, indexing etc.—to structural reforms such as the introduction of individual, funded retirement savings accounts or notional accounts. PROST can handle provident fund schemes as well as pay-as-you-go systems as the starting point before reform.

The Projection Methodology is developed taking into account the demographic, economic and financial variables.

When it comes to population and demographics, it takes on board the population pyramid, life expectancy changes, the demographic structure and system dependency among other factors. Regarding finance, macro trends, trends in wages, pension benefits and financial flows are the most important variables.

PROST produces five output modules, all of which allow for analysis of the sensitivity of results to key demographic and economic parameters such as fertility, longevity, wage growth and interest rates. The modules are:

- 1.

Population projections, including life tables, population pyramids, population dependency ratios etc.

- 2.

Demographic structure: labour force and employment, numbers of contributors and beneficiaries, system dependency ratio.

- 3.

Financial flows: projections of wages, benefits, revenues and expenditures of the pension system, pension scheme balance and the implicit pension debt. The financial flows module also calculates the adjustments—to benefit levels or contribution rates—that would ‘balance’ the system, i.e. bring revenues and expenditures into line.

- 4.

Fundamental, systemic reform: this module illustrates the effect of a shift to a ‘multi-pillar’ regime, incorporating both a pay-as-you-go, defined-benefit pension and a funded, defined contribution scheme or exclusively one or the other. Again, it measures the impact on both the system finances and individuals’ pension entitlements, including measurement of transition costs. The total pension benefit and the value of each of the pillars are provided separately.

- 5.

Effects on sample individuals: the model works out contributions and benefits for different sample individuals, specified by age, sex, age of labour market entry, retirement age, earnings profile, mortality etc. With results for six different sample people per age cohort, the distributional effects of the current system and potential reforms can be assessed both within and between generations.

In line with the new philosophy of public management, the need to develop and refine monitoring tools and the proposal of financial reporting for heritage we propose this aggregate accounting model based too on the three presentation concepts to guide presentation decisions for general purpose financial reports (GPFRs). Using PROST as our basis we set up a specific information model for BSAB as follows:

- a)

an aggregate accounting model for forecasting spending on BSAB and the revenue required to fund it;

- b)

various hypotheses concerning the economy and demographics as a whole, particularly future demographic trends such as changes over time in fertility rates, migration flows and life expectancy, and in economic conditions, especially future labour market participation and employment rates, wages, productivity rates and interest rates (European Economy 2/2012 and PROST); and

- c)

so-called institutional factors or rules of the pension system that determine the level of coverage of the system, access to and amount of pensions (Boado, Settergren, & Vidal-Meliá, 2011).

One advantage of this model is that it works as both a tool for providing the required level of transparency and an indicator of the solvency, sustainability and financial soundness of the system in place for funding BSAB. As an information system, it can also provide incentives for improving financial management by eliminating or minimising the long-standing divergences between the time frame of policy planning and that of the system itself.

We believe that the model also some advantages, such as the separation and clarification of sources of funding, the creation of a reserve fun, the analysis and monitoring of changes over time in the system and, finally, the possibility of recording the effect of trends on different items in future cash flows.

The model proposed is an AAM with modifications: the main change introduced is that we use an accrual system instead of the cash accounting criterion used to date to provide better quality, more transparent information.

The main reason is that the cash-based accounting systems currently in operation in many countries may provide inappropriate incentives for decision makers. A cash-based system which does not require pension liabilities to be recorded and reported encourages politicians not to record or report them. No cash is exchanged today, i.e. there is no increase in reported spending and, therefore, no pressure to raise debt when the decision is made to offer increased pension benefits.

However, an accrual-based accounting system that requires pension liabilities to be reported will promote more careful analysis and could result in different decisions being made when factors such as the government's financial position, net worth, and long-term sustainability are considered (IFAC, 2014).

In other words, the information system designed seeks to show the following:

- 1.

the resources available and the total real and accrued obligations each year, i.e. accountability for financial resources;

- 2.

the commitment for future generations arising from the need to provision an equalisation fund that will be a drain on future resources, i.e. awareness of current and future economic capabilities and financial needs;

- 3.

the real and forecast cost of the benefit for the coming years, i.e. identifying and assessing resources; and

- 4.

the operation, consistency and integration of the comprehensive financial management system for BSAB.

The model used to collect financial information on social assistance benefit is presented in the form of a multi-year balance sheet (see Table 3). The concepts that make up the balance sheet for basic social benefit are explained in Annex 1. This model follows the accounting and actuarial balance sheet layout used by other researchers to analyse pension systems (Boado et al., 2011). Like actuarial balance sheets, it offers incentives to improve management by eliminating or at least reducing the habitual discrepancies between the time frame used by politicians and election planners and that of the system itself. The short-term outlook adopted by politicians often fails to fit into the reality of a system with an indefinite time frame. However, the model is not an actuarial balance sheet per se, because it does not calculate the amounts for items at their current value for base year prices but rather establishes values by means of forecasts that are corrected based on facts checkable on the effective balance sheet date.

The intention with this financial information system is to depoliticise the management of BSAB by taking measures with a long-term planning time frame so as to achieve greater inter- and intra-generational equity. We believe that it may therefore be useful in management accounting and could be used not only to attain the desired levels of accountability but also as a tool for monitoring and managing the sources of funding needed to cover any potential BSAB scheme.

The items on the asset side are contributions already being paid by the state and by Spain's autonomous communities that would be reassigned to cover BSAB, and contributions paid by wage earners as necessary to cover that benefit (Annex 2). Alongside this state funding, it is advisable to provision a reserve fund which can be used to provide funding when necessary to avoid time lags and deficits. Sufficient reserve funding to cover 2 months of payments is considered here.

We also consider an equalisation or stabilisation fund to cater for adverse economic effects in the short term. This fund would serve to offset the difference between the origin and application of funds in the second half of each period, and would work as follows: a constant contribution rate of wages is set so that funding is generated at the beginning of each period and used later. From the 4th year onwards the contribution rate is recalculated to generate the equalisation fund so that contributions can be kept constant over a four-year time frame.

This enables the amounts required each year to fund the benefits paid to different groups of people to be calculated, along with the percentage of the respective totals represented by each asset account and each liability account.

The forecasts made to calculate each asset and liability item in the balance sheet as shown in Table 3 are the following:

- 1)

Demographic trends: a breakdown of the population structure by age groups provides information on the potential number of contributors and the number of people who will reach pension age in the coming years. The general population data that need to be studied include breakdowns of the population by age and gender, fertility rates, the percentage of births for each gender, mortality rates, immigration and emigration rates and their variations (Plamondon et al., 2000).

- 2)

Economic trends: the main economic variables considered in our study are the following:

- •

GDP: the percentage of GDP earmarked for BSAB is used to measure the level of expenditure that an efficient, forward-looking public administration could undertake without problems even in the most adverse circumstances.

- •

Variations in the consumer price index for basic products to be covered by basic income benefit: given that the financing model proposed is intended to fund this basic benefit for 12 years, and that the benefit is intended to cover spending on basic necessities, variations in the prices of the relevant goods must be taken into account.

- •

The variation in the discount rate for the benefit.

- •

- 3)

The labour market: the main variables that determine the structure of and potential changes in the labour market are the trend in wages, the variation in the number of individuals who switch from one employment status to another, e.g. from employed to unemployed, from employed to retired and from unemployed to employed and the number of new individuals who join the market.

The model proposed here can be used in management accounting as a tool not just for attaining accountability but also for controlling and managing the sources of funding required to cover a potential BSAB. Implementing a financial/accounting information system for such benefits would help to reorganise the current tangle of minimum income subsidies being paid around the country.

This accounting model corresponds to the principles of financial information because it is able to improve transparency, providing full information about the resources needed. It establishes a multi-year framework and budgeting situation in line with the economic situation and economic policy objectives and in compliance with the principles of budgetary stability and financial sustainability. Is achieves comparability between drawing up medium-term budgets and the principle of one-year periods under which budgets are approved and implemented.

Some limitations must be pointed out: the model is drawn up for a specific social aid called BSAB which is not a current aid. However, it could be implemented in the future and in view of its huge cost we seek to offer a financial and accounting model for it. Moreover, this model can be extrapolated to other current aids, which are being paid for and financed with no knowledge of where the financial resources come from.

In regard to the limits of disclosure of information on this issue, it is true that citizens have limited expertise and resources (time) to process data properly. As one possible solution, we would like to conduct research in the future into a self-regulation initiative that includes audit procedures executed by an ‘independent’ agency that first needs access to the relevant data, secondly expertise in financial matters and thirdly proper incentives to monitor public expenditure. However, self-regulation initiatives have their critics, who cast doubt on their credibility and argue that the border between regulator and regulated becomes blurred (Mäkinen & Kourula, 2012).

With its multi-year time frame and the breakdown of items that it includes, the proposed financial information system provides enhanced information on the origin and application of funds earmarked for covering basic social assistance benefit in Spain. It reveals details on how the funds for this benefit would be applied depending on the employment status of the recipient, and also on the sources of the funding used and the time frame covered. All of this reduces any political risks in terms of decisions made by politicians, who have conventionally used time frames of only 4 years and sometimes only one year for planning, given that the accounting information systems currently used in public sector budgeting are based on one-year periods.

The model marks a change in the way in which public funding is managed, and we hope that it will provide an adequate response to the increasing demand in society for transparency in the management of public finances.

This model is not intended to replace the current accounting model in the public sector. It is an attempt to enhance the quality of the information given and provide an additional tool for detailed accounting reporting. As a result, it could also be used in various countries. All countries spend huge amount of citizens’ money without showing how it is used.

Following the new philosophy of public management and the need to develop and refine monitoring tools, especially aimed at assessing achievements and results, we propose this aggregate accounting model, because we believe that there is an important role for accounting and performance measurement in increasing transparency and improving policy making in different contexts and decision situations.

In Spain the budget is the only instrument which is published, because there is no obligation to show financial statements. However, the Spanish Government should follow the example of other European countries in giving as much information as possible, such as financial statements and the accounting model proposed here, in order to increase transparency and raise the level of confidence of citizens.

Conflicts of interestWe declare that we have not conflict of interest.

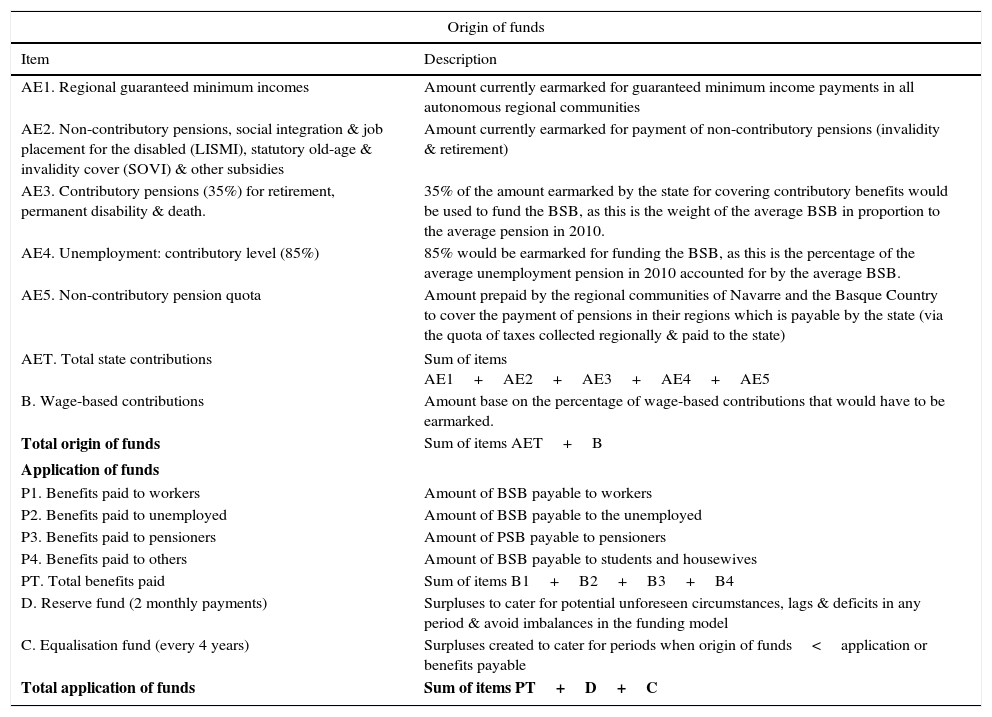

| Origin of funds | |

|---|---|

| Item | Description |

| AE1. Regional guaranteed minimum incomes | Amount currently earmarked for guaranteed minimum income payments in all autonomous regional communities |

| AE2. Non-contributory pensions, social integration & job placement for the disabled (LISMI), statutory old-age & invalidity cover (SOVI) & other subsidies | Amount currently earmarked for payment of non-contributory pensions (invalidity & retirement) |

| AE3. Contributory pensions (35%) for retirement, permanent disability & death. | 35% of the amount earmarked by the state for covering contributory benefits would be used to fund the BSB, as this is the weight of the average BSB in proportion to the average pension in 2010. |

| AE4. Unemployment: contributory level (85%) | 85% would be earmarked for funding the BSB, as this is the percentage of the average unemployment pension in 2010 accounted for by the average BSB. |

| AE5. Non-contributory pension quota | Amount prepaid by the regional communities of Navarre and the Basque Country to cover the payment of pensions in their regions which is payable by the state (via the quota of taxes collected regionally & paid to the state) |

| AET. Total state contributions | Sum of items AE1+AE2+AE3+AE4+AE5 |

| B. Wage-based contributions | Amount base on the percentage of wage-based contributions that would have to be earmarked. |

| Total origin of funds | Sum of items AET+B |

| Application of funds | |

| P1. Benefits paid to workers | Amount of BSB payable to workers |

| P2. Benefits paid to unemployed | Amount of BSB payable to the unemployed |

| P3. Benefits paid to pensioners | Amount of PSB payable to pensioners |

| P4. Benefits paid to others | Amount of BSB payable to students and housewives |

| PT. Total benefits paid | Sum of items B1+B2+B3+B4 |

| D. Reserve fund (2 monthly payments) | Surpluses to cater for potential unforeseen circumstances, lags & deficits in any period & avoid imbalances in the funding model |

| C. Equalisation fund (every 4 years) | Surpluses created to cater for periods when origin of funds<application or benefits payable |

| Total application of funds | Sum of items PT+D+C |

Source: Own work.

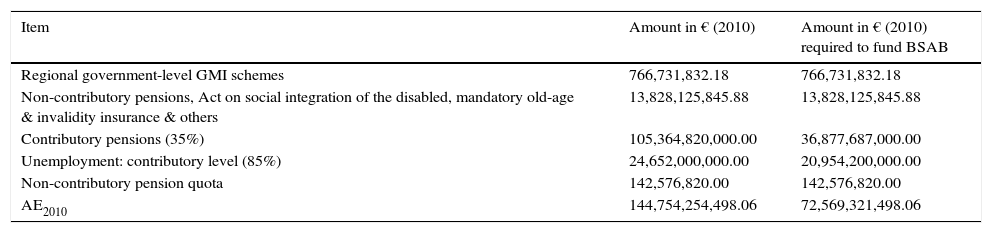

| Item | Amount in € (2010) | Amount in € (2010) required to fund BSAB |

|---|---|---|

| Regional government-level GMI schemes | 766,731,832.18 | 766,731,832.18 |

| Non-contributory pensions, Act on social integration of the disabled, mandatory old-age & invalidity insurance & others | 13,828,125,845.88 | 13,828,125,845.88 |

| Contributory pensions (35%) | 105,364,820,000.00 | 36,877,687,000.00 |

| Unemployment: contributory level (85%) | 24,652,000,000.00 | 20,954,200,000.00 |

| Non-contributory pension quota | 142,576,820.00 | 142,576,820.00 |

| AE2010 | 144,754,254,498.06 | 72,569,321,498.06 |

Source: own work using data from IGAE (Govt. Comptroller's Office). Ministry of the Treasury & Public Administration, 2010

The specific balance sheet shown in Table 3 takes 2010 as its base year. The figure for total state contributions in that year is used to work out what percentage of those contributions would need to be earmarked for BSAB. Once the percentage of state spending (see Annex 2, column 2) that needs to be earmarked for this benefit and the amounts payable to each individual are known (Peña-Miguel et al., 2015), it is possible to calculate what percentage of each individual contribution currently made by the state would be reallocated to fund BSAB (Peña-Miguel & De La Peña, 2017):

- -

All current contributions to guaranteed minimum income (GMI) schemes at regional government level would be switched to BSAB, as the latter entails larger amounts than the former.

- -

All current non-contributory pensions are lower than the BSAB, so they would be absorbed into it and the whole of the state's contribution to this item would be reallocated to the benefit.

- -

35% of the state's contribution to covering contributory pensions would be devoted to the BSAB, as the benefit is equivalent to that proportion of the average pension amount.

- -

85% of the amount paid by the state in unemployment benefits would be used for funding BSAB, as the benefit is equivalent to that proportion of the average unemployment benefit.

- -

Finally, given that all the current non-contributory pensions are lower than the BSAB, the whole of the amount paid as a “non-contributory pension quota” should be earmarked for the benefit.