To describe the urinary levels of molecules related to removing apoptotic cells and triggering inflammation, as well as cytokines involved in Colombian patients with systemic lupus erythematosus without and with lupus nephritis compared to healthy controls.

Materials and methodsUrine samples were taken from three groups of patients: healthy controls (n = 7), patients with systemic lupus erythematosus without lupus nephritis (n = 7), and patients with lupus and lupus nephritis (n = 4). The urine sample was collected and concentrated by ultrafiltration. A western blot evaluated HMGB1, HISTONE H3, CALRETICULIN (CRT), ANNEXIN A1 and CD46, CX3CL1 by ELISA and cytokines such as IL-8, IL-6, IL-12p70, TNF-α, and IL-1β by flow cytometry.

ResultsHistone H3 was detected in two patients, one with systemic lupus erythematosus without lupus nephritis and one with systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis. The detected band suggests a post-translational modification. There were no differences between the levels of HMGB1 and CX3CL1 in the study groups. CD46, ANNEXIN A1, and CRT were not detected in our samples. When evaluating cytokines in urine, an increase in IL-8 was observed in the group of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus without nephritis compared to controls. For IL-6, an increase was found among patients without lupus nephritis when compared with patients with lupus nephritis. No differences were found between the urinary levels of the other cytokines evaluated (IL-12p70, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-10).

ConclusionUrinary histone H3 and IL-8 levels may be interesting molecules to be evaluated in more patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, while HMGB1 and CX3CL1 are not useful. Further evaluation of patients is required to confirm these findings.

Describir los niveles urinarios de moléculas relacionadas con la remoción de células apoptóticas y desencadenamiento de la inflamación, así como citocinas involucradas, en pacientes colombianos con lupus eritematoso sistémico sin y con nefritis lúpica, en comparación con controles sanos.

Materiales y métodosSe tomó una muestra de orina a tres grupos de pacientes: controles sanos (n = 7), pacientes con lupus eritematoso sistémico sin nefritis lúpica (n = 7) y pacientes con lupus y nefritis lúpica (n = 4). La muestra de orina fue recolectada y concentrada por ultrafiltración. Se evaluó por western blot: HMGB1, histona H3, calreticulina (CRT), anexina A1 y CD46, CX3CL1 por Elisa y citocinas como IL-8, IL-6, IL-12p70, TNF-α e IL-1β por citometría de flujo.

ResultadosLa histona H3 se detectó en dos pacientes, uno con lupus eritematoso sistémico sin nefritis lúpica y uno con lupus eritematoso sistémico y nefritis lúpica. La banda detectada sugiere una modificación postraduccional. No hubo diferencias entre los niveles de HMGB1 y CX3CL1 en los grupos de estudio. CD46, anexin A1y CRT no se detectaron en nuestras muestras. Al evaluar las citocinas en orina, se observó un incremento de IL-8 en el grupo de pacientes con lupus eritematoso sistémico sin nefritis, en comparación con los controles, en tanto que para la IL-6, se encontró un aumento en pacientes sin nefritis lúpica, en comparación con pacientes con nefritis lúpica. No se hallaron diferencias en los niveles urinarios de las demás citocinas evaluadas (IL-12p70, TNF-α, IL-1β e IL-10).

ConclusiónLos niveles urinarios de histona H3 e IL-8 pueden ser moléculas interesantes para ser evaluadas en un grupo más amplio de pacientes con lupus eritematoso sistémico, mientras que la HMGB1 y CX3CL1 no parecen ser útiles. Se requiere evaluar más pacientes para confirmar estos hallazgos.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease characterized by the production of autoantibodies directed against intracellular antigens. The clinical characteristics are heterogeneous and with varying degrees of severity. In Colombia, between the years 2012 and 2016, a lupus prevalence of 91.9/100,000 subjects was estimated, where 79% of the patients were women.1 The lack of removal of apoptotic cells has been proposed as a mechanism of disease induction,2,3 and thus urine becomes attractive as a source for the study of potential biomarkers in an observation window to know the patient's status. A biological marker is defined as a physical, cellular, biochemical, molecular sign or a genetic alteration, by which a normal or abnormal biological process can be recognized and measured.4 Some promising markers, but with inconclusive studies, are the variants of the constant fraction for the immunoglobulin G receptor, which play an important role in immune clearance and may contribute to greater susceptibility to the disease, especially in the Caucasian population; however, it has not been possible to find a clear association with the risk of lupus nephritis.5 Among other molecules that have been found to be more associated with lupus nephritis is the chemokine MCP-1 (monocyte chemoattractant protein).6 On the other hand, there is no validated biomarker of disease activity in SLE patients with different levels of activity at the same time.4

Recently, the deposition of C4d in renal tissue and its concentration in the urine and serum of patients has been evaluated as a promising marker for renal lupus nephritis.5,7 However, an association was found with CD4d present in the tissue, which makes its measurement difficult. In another study, in which plasma levels of C4d were evaluated, it was found that it could be a biomarker to discriminate between SLE patients with and without nephritis, and greater precision was found when evaluating the C4d/C4 ratio and relating it to histology,7 which makes it attractive as an ideal biomarker in this case, as it is easy to measure, not affected by age, sex or race, reflects disease activity, detects involvement early and correlates with histology. The pathophysiology of lupus nephritis involves several mediators such as chemokines, adhesion molecules, autoantibodies, cytokines, complement and its products.6 Through proteomics in kidney biopsy tissue from patients with class IV lupus nephritis, multiple markers have been identified: serotransferrin, cytokeratin 18 and 19, albumin and annexin A5, alpha-1-antitrypsin (A1AT), CKD273 uromodulin, S100-A9 protein fragments, beta-2-microglobulin and alpha-2-HS glycoprotein.4,8 Another marker, MiRN-29c, has been suggested to be a marker of early progression to fibrosis in lupus nephritis9; nevertheless, among the most studied are MCP-1, TWEAK, NGAL, IP10 PGDS.6 Recently, in Colombian patients, the usefulness of transferrin and urinary ceruloplasmin to differentiate patients with SLE without and with nephritis was evaluated, and it was found that both molecules can discriminate patients with active lupus nephritis.10

Since lupus nephritis is the major complication observed in these patients, in the present study we sought to explore some molecules related to the removal of apoptotic cells and cytokines in urine of patients with SLE with and without lupus nephritis.

Materials and methodsPatients and controlsAll patients and study controls were recruited in Bogotá (Colombia). For patients diagnosed with SLE, those over 18 years of age who were being followed up at a reference hospital and who met the SLICC 2012 classification criteria were selected.11 Eleven patients who met these criteria were obtained, four of whom had documented renal involvement type lupus nephritis class III or IV diagnosed by renal biopsy, which was documented according to the classification criteria of the International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society (ISN/RPS) of 200312 Adults over 18 years of age of the same sex and age as the patients were chosen as controls, and were also evaluated by a rheumatologist to rule out the presence of autoimmune disease or other pathologies. Some controls were used for more than one patient. It was also evaluated by urinalysis that they did not present proteinuria, hematuria or active sediment.

SLE group without lupus nephritisInclusion criteriaPatients with established SLE, followed by rheumatology at the Hospital Universitario San Ignacio who did not present proteinuria, hematuria, active sediment or renal failure according to clinical assessment and laboratory tests at the time of consultation.

Exclusion criteriaPatients who are not adherent to treatment; presence of bacteria in the urinary sediment.

SLE group with lupus nephritisInclusion criteriaPatients with SLE and diagnosed with lupus nephritis with renal biopsy; patients in established stage III and IV of lupus nephritis. A proteinuria below 500 mg/24 h will be considered inactive nephritis, while above 500 mg/24 h it will be considered active.

Exclusion criteriaPatients who are not adherent to treatment; patients on dialysis; presence of bacteria in the urinary sediment.

Control groupInclusion criteriaAdult volunteers who did not present proteinuria, hematuria, active sediment in urinalysis at the time of sample collection nor clinical manifestations of SLE.

Exclusion criteriaPresence of bacteria in the urinary sediment.

The patients were assessed in the hospitalization service or outpatient clinic of rheumatology, and those who met the criteria and agreed to participate were asked to sign an informed consent; data of the last evaluation were taken from the medical history and a urine sample was collected to perform the analyses in the laboratory. All patients underwent a complete clinical assessment and the necessary paraclinical tests were requested for the calculation of the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI).13 Proteinuria was also classified in an isolated sample with the proteinuria/creatinuria ratio and/or in 24 h urine, which was considered normal if it was lower than or equal to 150 mg/24 h, subnephrotic range 150−3500 and nephrotic range > 3500 mg. The presence of more than five leukocytes per field, more than two red blood cells or presence of casts was considered active sediment. The rest of the data were taken from the medical record to evaluate, among others, the presence of comorbidities such as diabetes and arterial hypertension (AHT). This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee.

The first urine sample of the morning was collected and concentrated by ultrafiltration with Amicon® ultra tubes of 15 ml, for which a cut off of 10 KDa was used. For this, 4 ml of urine were taken and then the tubes were centrifuged at 4000×g (gravity), 30 min at room temperature. Finally, the concentrate was recovered in 200 μl of phosphate buffered saline with protease inhibitor PMSF (phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, P2676, Sigma). 25 μg of protein per lane were seeded in precast gels (Biorad, 4–20% Ready Gel Tris-HCl gel, 12 well, 20 μl #1611177) and an SDS-PAGE electrophoretic run was performed for 10 min at 100 V (volts) and 35 min at 200 V. Once the electrophoretic run was completed, the proteins were transferred to a Polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane in a humid chamber at 0.35 A (ampere) for 2 h, at room temperature. Membrane blocking was performed with 5% skim milk in TBS (Tris-buffer saline, 1706435, Biorad) for one hour. Subsequently, the membrane was incubated with the respective detection antibodies for one hour, at room temperature; 1:500 rabbit anti-HMGB1 polyclonal primary antibody (MAB1690, cell signaling), 1:1,000 of the mouse anti-histone H3 monoclonal primary antibody (MAB9715, cell signaling). Each membrane was washed with a TBS solution five times for 5 min, and then the respective anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody was added, 31460 Thermofisher (1:5,000) or anti-mouse IgG, 31430, Thermofisher (1:10,000) conjugated with peroxidase for one hour at room temperature and in agitation. The membranes were washed five times for 5 min and then revealed with a luminol solution (Supersignal™ west dura extended, 34076, Pierce). Finally, the membranes were exposed with an X-ray film (CL-XPosure™ film, 34093, Thermo Scientific) and were developed. The procedure was repeated for CRT (anti-calreticulin, 2891, cell signaling), annexin A1 (anti-annexin A1, 3299, cell signaling) and CD46 (anti-CD46, 13241, cell signaling) with the standardization described for each molecule. The relative density for each protein was calculated using the ImageJ software.

Fractalkine ELISA (CX3CL1)From a concentrated urine sample, a 1:20 dilution was made and the fractalkine CX3CL1 was detected by ELISA, following the instructions of the manufacturer (Human CX3CL1/Fractalkine Quantikine ELISA Kit, DCX310, R&D systems). Briefly, the diluted urine sample and the respective standard curve from 0 to 10 mg/mL were added to the plate already coated with capture antibody and incubated for 3 h at 4 °C. After this, washes were done with buffer and the detection antibody coupled to peroxidase was added for one hour at 4 °C. The washing process was repeated and the ELISA was revealed with TMB and hydrogen peroxide, using H2SO4 as stop solution. Reading was done at 450 nm in a ThermoScientific spectrophotometer. The determination of the concentration of fractalkine in the sample was made by interpolating the optical density values on the standard curve. The sensitivity limit was 0.072 ng/ml.

Measurement of cytokinesThe concentrations of IL-8, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α and IL-12 in the urine samples were analyzed by flow cytometry, using the microsphere technique of the CBA commercial kit: Cytometric bead array human inflammation kit (Human Inflammatory Cytokines kit, BD Biosciences, San José, CA), following the procedure established by the commercial house. A standard curve was performed by making serial dilutions (0–5000 pg/ml). Subsequently, each of the dilutions and diluted samples were mixed with the capture beads for each of the cytokines under evaluation. Finally, the detector fluorochrome was added. The samples were acquired in the FACS Aria IIu cytometer. The concentration of each of the cytokines was calculated by analysis using the FCAP Array software, Windows version (BD, Biosciences). The limit of detection depended on each cytokine analyzed and ranged between 1.9 and 7.2 pg/ml.

Statistical analysisThe data were analyzed using STATA (14.0) (StataCorp; College Station, TX), while the normality of the variables was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk W test. A non-parametric Mann–Whitney test was used for comparison between the groups. It was considered a statistical significance <0.05. The Graphpad prism 5.0 software was used to create the graphs and analyze the data.

Ethical considerationsThe project took into account the sections of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Colombian regulations (Resolution 8430 of 1993). The authors declare that the research conducted on humans was endorsed by the institutional ethics committee. Likewise, no patient data appear in this article and all patients signed informed consent.

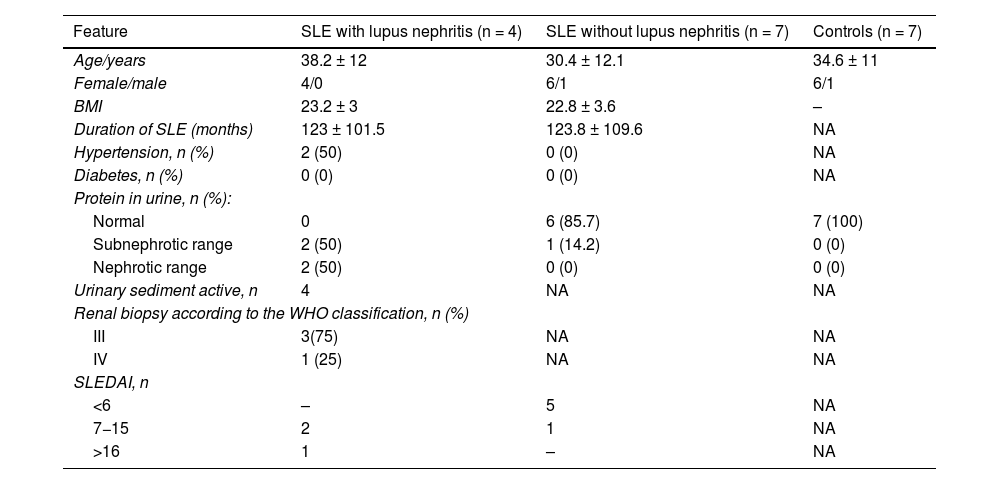

ResultsCharacteristics of the study populationThe characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the participants was 38 years in the group of SLE with lupus nephritis and 30 years in the group of SLE without lupus nephritis. The majority of participants were women (90.9%). In the group with lupus nephritis, 50% of the participants had proteinuria in the nephrotic range, while 75% of them had a diagnosis of class III lupus nephritis (Table 1).

Characteristics of the study population.

| Feature | SLE with lupus nephritis (n = 4) | SLE without lupus nephritis (n = 7) | Controls (n = 7) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age/years | 38.2 ± 12 | 30.4 ± 12.1 | 34.6 ± 11 |

| Female/male | 4/0 | 6/1 | 6/1 |

| BMI | 23.2 ± 3 | 22.8 ± 3.6 | – |

| Duration of SLE (months) | 123 ± 101.5 | 123.8 ± 109.6 | NA |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 2 (50) | 0 (0) | NA |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA |

| Protein in urine, n (%): | |||

| Normal | 0 | 6 (85.7) | 7 (100) |

| Subnephrotic range | 2 (50) | 1 (14.2) | 0 (0) |

| Nephrotic range | 2 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Urinary sediment active, n | 4 | NA | NA |

| Renal biopsy according to the WHO classification, n (%) | |||

| III | 3(75) | NA | NA |

| IV | 1 (25) | NA | NA |

| SLEDAI, n | |||

| <6 | – | 5 | NA |

| 7−15 | 2 | 1 | NA |

| >16 | 1 | – | NA |

In order to evaluate the presence of molecules related to the removal of apoptotic cells in the urine of the patients, HMGB1, CX3CL1, CD46, calreticulin, CRT, histone H3 and annexin A1 were evaluated.

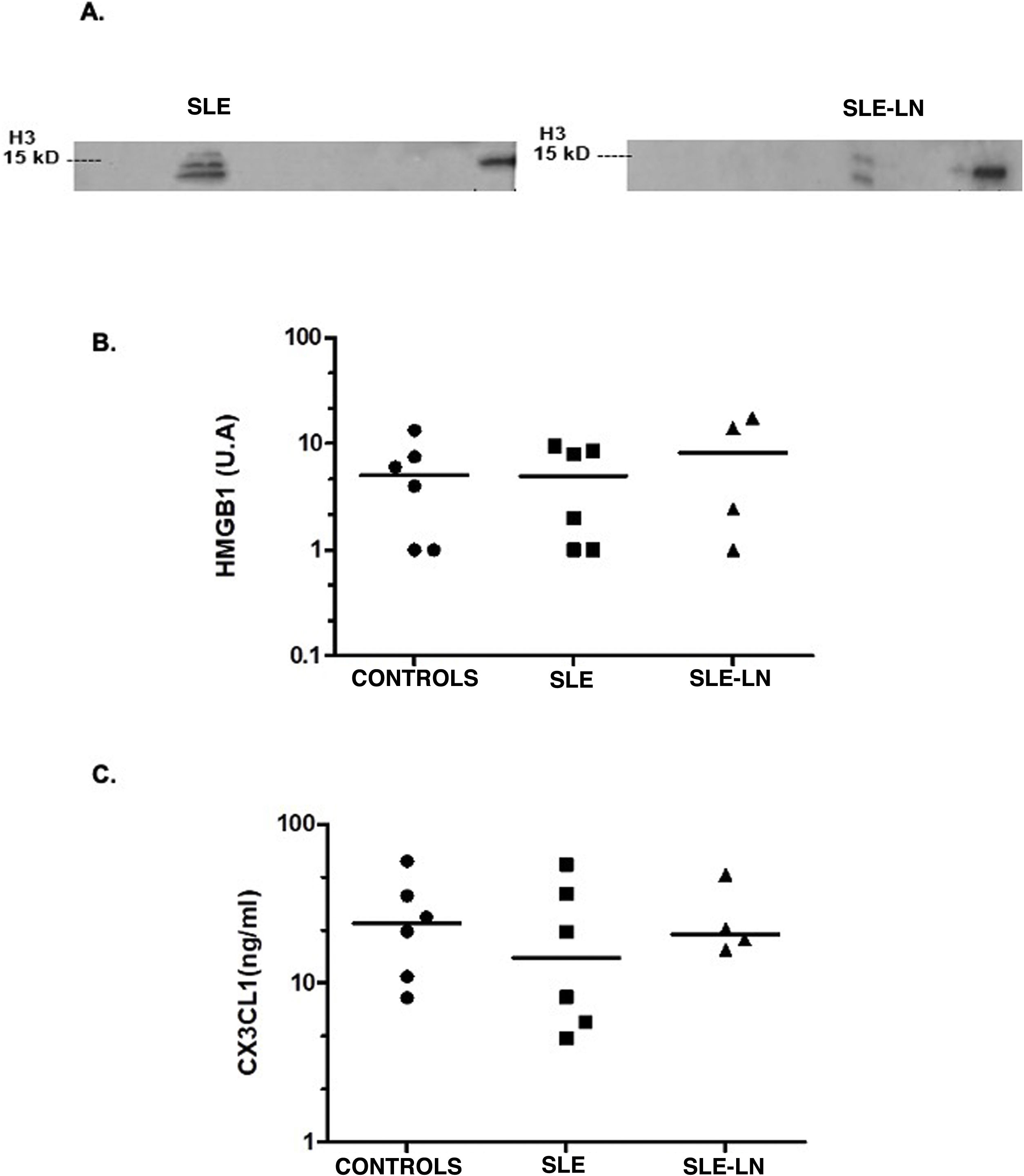

As can be seen in Fig. 1A, histone H3 as a "danger signal" was detected in two patients with SLE, one with lupus nephritis and the other without this entity. The band detected suggests a post-translational modification of the histone. This histone H3 was not detected in the control individuals. No differences were found in HMGB1 levels in the groups analyzed (expression median 5.01 vs. 8.2 in controls, SLE and SLE with nephritis, respectively, Fig. 1B). For the level of CX3CL1 as a chemoattractant molecule, it was similar in all groups (median of 23.7 ng/ml for controls vs. 14.6 ng/ml for SLE and 20.4 ng/ml for SLE and lupus nephritis, Fig. 1C). CD46, annexin A1, or CRT were not detected in the samples of the patients and controls evaluated.

Levels of histone H3 (A) and HMGB1 (B) detected by Western Blot and of CX3CL1 (C) by ELISA.

Black circles: controls; black squares: patients with SLE without lupus nephritis; black triangles: patients with SLE and lupus nephritis. The horizontal line represents the median. U: arbitrary units.

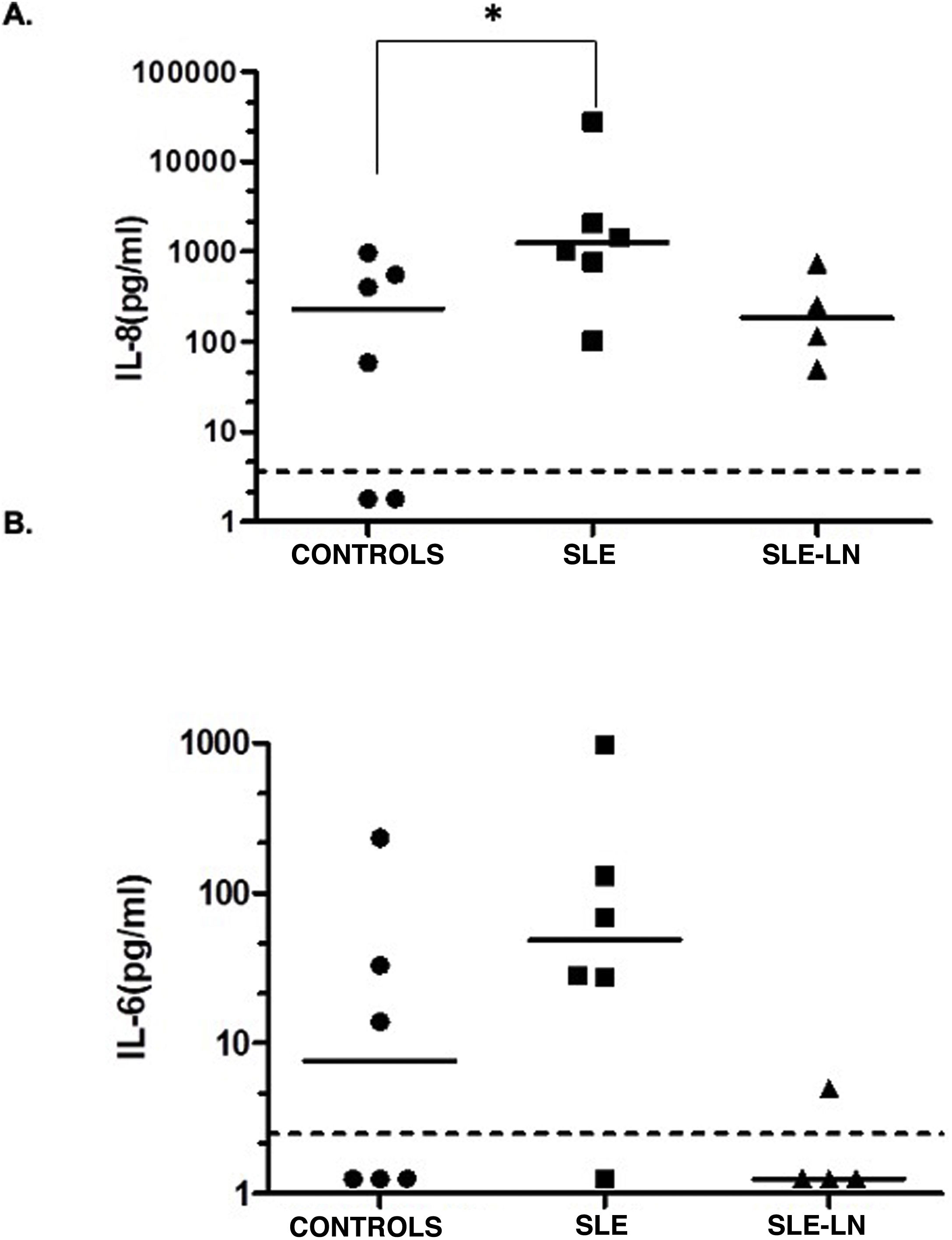

When evaluating cytokines in urine, a statistically significant increase was observed when comparing IL-8 levels in patients with SLE without lupus nephritis and controls (production median of 231.1 pg/mL for controls vs. 1235.5 pg/ml for the patients with SLE without lupus nephritis) (Fig. 2A, p < 0.05). No differences were found in the levels of IL-8 of the patients with SLE and lupus nephritis when compared them to the controls (production median of 231.1 pg/ml for the controls vs. 182.1 pg/ml for the patients with SLE and nephritis). For IL-6, no significant differences were found between controls and patients; however, a tendency to increase was observed in the patients with SLE without nephritis compared to the controls (median of 48.9 pg/ml for SLE without nephritis vs. 7.6 pg/ml for controls). Low urinary levels of IL-6 were detected in patients with SLE and nephritis, while a decrease was observed in patients with SLE compared to patients with SLE and lupus nephritis (median of 1.25 pg/ml, Fig. 2B). The other cytokines evaluated in urine (TNF-α, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-1β) were found below the detection limit in the groups analyzed (data not shown).

Levels of IL-8 (A) and IL-6 (B) in urine.

Black circles: controls; black squares: patients with SLE without lupus nephritis; black triangles: patients with SLE and lupus nephritis. The horizontal line represents the median and the dotted line represents the limit of detection of the test. * p < 0.05. Mann Whitney test.

In this study, the presence of histone H3 was found in two of the patients with lupus, one with lupus nephritis and the other without lupus nephritis, and it was not observed in any of the controls (Fig. 1A). In both patients, a band corresponding to histone H3 was detected, which may be presenting a post-translational modification of the histone. The release of this histone suggests that it may be being released by apoptotic bodies and cause inhibition of capture by macrophages, thereby triggering the inflammation process.14,15 Histones are an essential component of eukaryotic nucleosomes, which are molecules with several important roles in the DNA: they can be released from activated inflammatory cells, apoptotic cells, and necrotic cells.16 When exposed extracellularly, they can generate an inhibition in the uptake of apoptotic cells by phagocytes, possibly due to their binding to integrin αvβ5, which recognizes molecules such as Gas6 and MFG-E8 that function as a bridge between the exposure of phosphatidylserine exposed in apoptotic cells for recognition by phagocytes and this integrin.17

In SLE this molecule can be exposed by apoptotic cells that are not efficiently removed. Histone H3 may undergo some modifications, including trimethylation. These types of modifications promote an immunogenic potential that, when recognized by antigen-presenting cells, can be presented to autoreactive T cells, and these in turn promote the production of antibodies by B cells, which will lead to a deposit of immune complexes in different organs.18

The HMGB1 molecule has been considered a "danger signal" type molecule. When this molecule is released, it participates in the release of pro-inflammatory molecules through recognition by RAGE, TLR2 or TLR4 receptors, which generates an inflammatory environment and contributes to autoimmune disorders. This molecule can be released from activated macrophages,19 as well as from cells in secondary necrosis20; in addition, it can avoid the recognition and phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages, by binding with integrin αvβ3, which prevents the interaction between this integrin and MFG-E8, an opsonin that serves as a binding bridge between the phosphatidylserine exposed on apoptotic cells and integrin αvβ3. On the other hand, HMGB1 can inhibit intracellular

signaling pathways, such as phosphorylation of ERK and activation of Rac-1, which are activated in the macrophages during the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells.21 In a study that measured the levels of HMGB1 in the urine of patients with lupus nephritis by Western Blot, it was proven that the increase in the levels of this molecule in urine is particularly correlated with active lupus nephritis and with the SLEDAI score of these patients.22 In our study we did not find differences in the levels of HMGB1, which may be due to the sample size or the processing of the urine, since in this work it was concentrated by ultrafiltration. However, a role of this molecule cannot be ruled out, since its oxidation-reduction state can determine its inflammatory role.23

Fractalkine (CX3CL1) is a chemokine synthesized by endothelial cells that in its soluble form binds to its receptor (CX3CR1) present in monocytes, NK cells and T lymphocytes, which facilitates their recruitment24; it has been demonstrated that it participates as a chemoattractant signal in the removal of apoptotic cells.25 It has been observed that the expression of fractalkine in the serum of patients with SLE can function as a marker of disease activity and severity, since high concentrations have been found in patients with SLE and neuropsychiatric involvement; in addition, its measurement in cerebrospinal fluid can help in the diagnosis of these patients.26

In addition, it has been described that there is an increased expression of fractalkine in patients with lupus nephritis. A study that analyzed the expression of this molecule by immunohistochemistry of biopsies from patients with lupus nephritis revealed elevated levels of fractalkine in renal biopsies from patients with lupus nephritis grades III and IV.27 Similarly, in a study in which urinary fractalkine levels were measured by ELISA, higher levels of this molecule were found in patients with proliferative lupus nephritis, compared to patients with non-proliferative lupus nephritis.28 In our study, no differences were found in urinary fractalkine levels between patients and controls.

As mentioned above, the lack of removal of apoptotic cells leads to the induction of the release of different pro-inflammatory cytokines, thanks to the release of intracellular antigens that function as immunogenic signals and potential activators of various signaling pathways, such as NFκβ and MAPK, which end in the release of these cytokines and exacerbate the immune response, in addition to the damage to the different organs involved. With respect to cytokines, differences have been observed in urinary levels of IL-8 in patients with SLE with and without lupus nephritis, as well as in healthy controls and in patients with SLE and lupus nephritis.29 However, another similar study revealed that there are no significant differences between patients with and without lupus nephritis.30 In our study, higher levels of IL-8 were found in SLE patients without nephritis compared to controls, but these levels fell in patients with lupus nephritis, which may be due to the treatment received by the patients. It has been reported that after treatment with cyclophosphamide, the levels of IL-8 and IL-6 decrease.31 In this study, only one SLE patient without nephritis had received such treatment, which is why the effects of other medications such as glucocorticoids, antimalarials and immunosuppressants such as azathioprine should be considered. Urinary levels of IL-6 have been described as elevated in patients with lupus nephritis and have been correlated with high levels of anti-dsDNA32; however, in a recent research there was no difference in patients with SLE and ANA positive patients, nor in renal and non-renal patients.33 In our study we did not find differences between controls and patients, but when looking at the levels among patients, a trend towards higher levels was observed in patients with SLE without nephritis. The main weakness of our study is the small number of patients, which is why the data shown should be evaluated in studies with a larger number of patients; however, the results presented show that histone H3 and IL-8 appear to be molecules of interest for follow-up in patients with SLE: histone H3, to continue understanding the mechanisms of failure in the removal of apoptotic cells and their role as a trigger of the inflammatory process; and IL-8, because few studies have been done and it could be useful for follow-up after treatment. In a study in Colombian patients with polyautoimmunity, it was found that plasma IL-8 is elevated in patients with polyautoimmunity associated with SLE and decreases after treatment with rituximab.34 The role of these two molecules present in urine must be confirmed by expanding the number of patients evaluated.

The growing need for better biomarkers to monitor renal involvement by SLE is still present. For this reason, it is necessary to continue the search, from translational medicine, for biomarkers that allow a better approach to lupus nephritis.

The elevation of IL-8 evidenced in our work correlates with previous studies that have evaluated the possibility of being a biomarker of kidney damage. This is supported by the more marked elevation of urinary IL-8 in patients with active lupus nephritis. Likewise, the decrease in urinary levels has been correlated with the treatment of nephritis and points to its possible use as a biomarker in clinical practice.35

Other markers of renal damage that have been described include the tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK), related to the expression of other inflammatory markers, which makes it a potential urinary biomarker of kidney damage, and may even be associated with episodes of acute activity and response to treatment.36

Authors' contributionYeimy Paola Trujillo: Research, analysis and writing of the article.

Alfonso Kerguelén: Writing of the article and analysis

Sandra Amado: Conceptualization, inclusion of patients, supervision, editing and review of the article.

Santiago Bernal-Macías: Inclusion of patients, editing and review of the article.

Luz-Stella Rodríguez: Conceptualization, research, analysis, review and editing of the article, obtention of funding.

Daniel Gerardo Fernández-Ávila: Inclusion of patients, supervision, editing and review of the article.

Alfonso Barreto-Prieto: Conceptualization, research, analysis and supervision.

Ethical considerationsThe entire research was approved by the institutional committee (Act No. 17-2014).

FundingThis Project received funding from the Vice-Rectorate for research of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (PPTA6433).