While numerous studies have examined the physical consequences of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), its impact on sleep quality remains relatively understudied.

ObjectiveThis study aims to specifically assess the effect of RA on patients’ sleep quality.

Materials and methodsWe conducted a cross-sectional study. Patient characteristics were assessed. The patients’ sleep quality was assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale (MOS-Sleep scale) in its validated Arabic version.

ResultsThe study included n=49 patients with RA. Their mean age was 54.1±12.06 years [24–83]. The mean diagnostic delay was 2.35 years [.5–13]. The RA was erosive in 46 cases (93.8%), two patients (4.1%) had atlantoaxial subluxation, and coxitis was noted in four cases (8.2%). A longer diagnostic delay was associated with a higher sleep problem index score. A significant positive association was found between VAS pain and all sleep disturbance scores (p=.00 and r=.518). The presence of comorbidities was associated with a higher index (p=.03). This was also true in case of coxitis and/or atlantoaxial subluxation (p=.03). For therapeutic management, we did not find a statistically significant association between the use of NSAIDs or corticosteroids, or methotrexate (MTX), and the sleep problem index. However, weekly dosage of MTX was positively correlated with the sleep problem index (p=.03, r=.358). The multivariate analysis found global patient assessment (GPA) (p=.000), presence of comorbidities (p=.007), and presence of atlantoaxial subluxation and/or coxitis (p=.05) were significant factors influencing sleep quality.

ConclusionDiagnostic delay and the global management of RA patients, including co-morbidities could impact sleep quality. Therefore, early treatment and holistic management of patients are necessary.

Aunque numerosos estudios han examinado las consecuencias físicas de la artritis reumatoide (AR), su impacto en la calidad del sueño sigue siendo relativamente poco estudiado.

ObjetivoEste estudio tiene como finalidad evaluar específicamente el efecto de la AR en la calidad del sueño de los pacientes.

Materiales y métodosRealizamos un estudio transversal. Se evaluaron las características de los pacientes. La calidad del sueño de los pacientes se evaluó utilizando la Escala de Sueño del Estudio de Resultados Médicos (MOS-Sleep scale) en su versión árabe validada.

ResultadosEl estudio incluyó a 49 pacientes con AR. Su edad promedio fue de 54,1±12,06 años [24–83]. El retraso en el diagnóstico fue en promedio de 2,35 años [0,5-13]. La AR fue erosiva en 46 casos (93,8%), dos pacientes (4,1%) tenían subluxación atlantoaxial, y se observó coxitis en cuatro casos (8,2%). Un mayor retraso en el diagnóstico se asoció con un índice de problemas de sueño más alto. Se encontró una asociación positiva significativa entre la escala VAS del dolor y todos los puntajes de trastornos del sueño (p=0,00 y r=0,518). La presencia de comorbilidades se asoció con un índice más alto (p=0,03). Esto también fue cierto en caso de coxitis y/o subluxación atlantoaxial (p=0,03). Para el tratamiento, no encontramos una asociación estadísticamente significativa entre el uso de AINEs o corticosteroides, metotrexato (MTX) y el índice de problemas de sueño. Sin embargo, la dosis semanal de MTX se correlacionó positivamente con el índice de problemas de sueño (p=0,03, r=0,358). En el análisis multivariado, la Evaluación Global del Paciente (GPA) (p=0,000), la presencia de comorbilidades (p=0,007) y la presencia de subluxación atlantoaxial y/o coxitis (p=0,05) fueron factores significativos que influyeron en la calidad del sueño.

ConclusiónEl retraso en el diagnóstico y el manejo integral de los pacientes con AR, incluyendo las comorbilidades, podrían afectar la calidad del sueño. Por eso, se requiere un tratamiento temprano y un manejo holístico de los pacientes.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most common chronic inflammatory rheumatic disease with a prevalence of 1% in the general population [1]. It evolves through successive inflammatory attacks leading to progressive joint destruction with deformities that can be the cause of a major handicap altering the quality of life of patients [2,3]. The consequences of RA are multiple: physical (pain, joint stiffness, deformity), emotional (depression, anxiety, stress, loss of self-confidence, impaired sleep quality), social (isolation) and economic (loss of productivity, absenteeism, sick leave) [4,5]. Many studies have focused on the physical impact of the disease, but its influence on sleep is often overlooked, despite the inconvenience it can cause to patients’ lives. Indeed, sleep has an impact on mortality [6] and according to a recent meta-analysis published in 2021, improving sleep quality leads to better mental health [7]. In this perspective, we conducted this study in order to focus on the impact of RA on the quality of sleep of patients.

MethodsData sourceWe conducted a longitudinal case-control, prospective study, including n=49 patients with RA followed at the rheumatology department of La Rabta Hospital in Tunis. Patients were included between January 2021 and November 2022.

Cohort selectionWe included patients of age≥18 years meeting the ACR/EULAR 2010 criteria and excluded: i) patients with poorly balanced RA in relapse, ii) those with severe disease-related comorbidity, iii) patients with difficulty in answering questionnaires.

Main outcomeThe impact of RA on sleep quality.

Study parametersA datasheet was developed. It included: age, gender, demographics, personal history, and RA characteristics such as: The number of tender joints (NTJ) and swollen joints (NSJ), the global patient assessment (GPA), the visual analogic scale (VAS) for pain assessment, duration of morning stiffness (MS), the HAD depression and HAD anxiety score and the health assessment questionnaire (HAQ). The assessment of RA activity was done through the Disease Activity Score (DAS28 CRP) [8]. For the assessment of sleep quality, we used the Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale (MOS-Sleep scale) in its validated Arabic version [9,10]. It is a 12-item measurement scale developed for patients with chronic diseases. It is divided into 6 dimensions assessing: sleep disturbance, snoring, shortness of breath or headache, sleep adequacy, daytime sleepiness, and sleep quantity. A sleep problem index summarizing the score of 9 MOS-Sleep items is also calculated. Responses are based on a retrospective assessment of the last four weeks. Regarding the method of calculation, ten out of 12 items are scored on a six-point Likert scale, one item uses a five-point Likert scale, and the item on sleep quantity is an open-ended question that records the actual number of hours of sleep. All items, except for the amount of sleep, are recalculated on a scale of 0 to 100. Higher scores indicate more severe sleep problems.

Data gatheringIt was carried out in the databases of PubMed (www.pubmed.com), ScienceDirect (www.sciendirect.com), and on Google (www.google.fr). We used the following keywords rheumatoid arthritis, quality of life, patient education, educational needs, self-management, and patient-centered care.

Patient follow-upFollow-up time started from January 2021 to November 2022.

Statistical analysisData were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24 software. A univariate study was carried out to identify the factors influencing sleep quality on the basis of socio-economic characteristics, comorbidities, disease characteristics and treatments received. In a second step, we performed a multivariate study of the factors influencing patients’ sleep after calculating the correlation with the data collected in the univariate study. This step allows us to select the variables retained as having a significant relationship in the univariate study and to subject them to a linear regression in order to eliminate any interdependence between the different variables. The significance threshold was set at 5%.

Ethical considerationsOur study began after obtaining free and informed consent from the patients recruited. The anonymity of the patients and the confidentiality of their information was respected. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethical committee of the La Rabta Hospital.

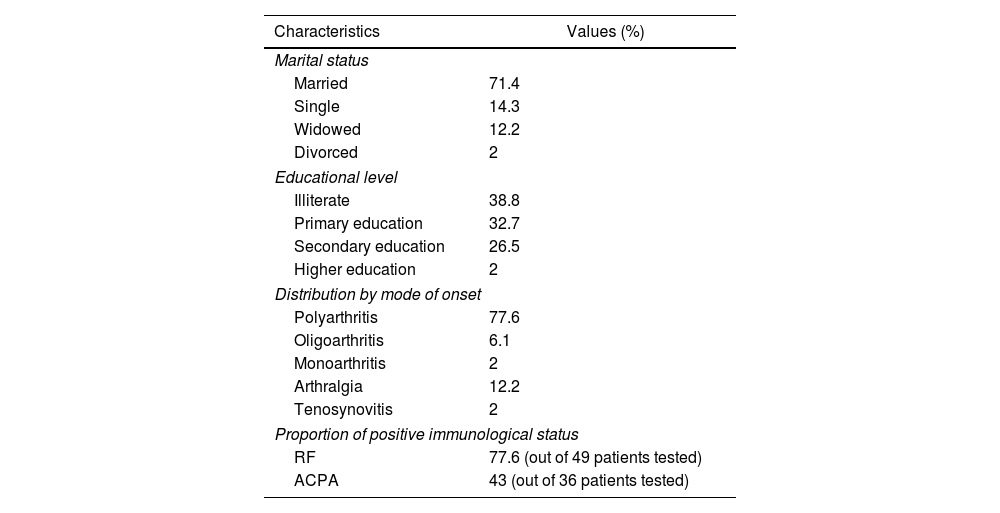

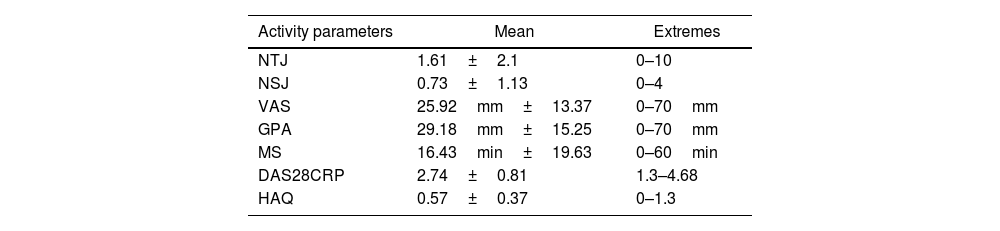

ResultsDescriptive studyThe mean age of the patients was 54.1±12.06 years [24–83]. A female predominance was noted with a sex ratio (M/F) of 0.11 (44 women (89.8%) and 5 men (10.2%)). Patients of urban origin were 75.5% of the study population. Thirty-four patients (69.4%) were unemployed at the index date. Comorbidities were mostly, diabetes (32.6%), followed by arterial hypertension (22.4%) and dyslipidemia (12.2%). One male patient was a smoker with a history of 30 pack-years, and he was still smoking. The mean RA duration was 11.43±7.32 years [2–29]. The diagnostic delay was at the mean of 2.35 years [0.5–13]. Table 1 illustrates our population's characteristics. The RA was erosive in 46 cases (93.8%), two patients (4.1%) had atlantoaxial subluxation, and coxitis was noted in four cases (8.2%). Table 2 shows the Assessment of rheumatoid arthritis activity at the index date. Other comorbid conditions included diffuse destructive bronchiectasis in four cases, rheumatoid pulmonary nodule in one case, and interstitial lung disease in three cases.

Clinical and immunological characteristics of the study population.

| Characteristics | Values (%) |

|---|---|

| Marital status | |

| Married | 71.4 |

| Single | 14.3 |

| Widowed | 12.2 |

| Divorced | 2 |

| Educational level | |

| Illiterate | 38.8 |

| Primary education | 32.7 |

| Secondary education | 26.5 |

| Higher education | 2 |

| Distribution by mode of onset | |

| Polyarthritis | 77.6 |

| Oligoarthritis | 6.1 |

| Monoarthritis | 2 |

| Arthralgia | 12.2 |

| Tenosynovitis | 2 |

| Proportion of positive immunological status | |

| RF | 77.6 (out of 49 patients tested) |

| ACPA | 43 (out of 36 patients tested) |

RF: rheumatoid factor, ACPA: anti citrullinated peptides antibodies.

Assessment of rheumatoid arthritis activity.

| Activity parameters | Mean | Extremes |

|---|---|---|

| NTJ | 1.61±2.1 | 0–10 |

| NSJ | 0.73±1.13 | 0–4 |

| VAS | 25.92mm±13.37 | 0–70mm |

| GPA | 29.18mm±15.25 | 0–70mm |

| MS | 16.43min±19.63 | 0–60min |

| DAS28CRP | 2.74±0.81 | 1.3–4.68 |

| HAQ | 0.57±0.37 | 0–1.3 |

NTJ: number of tender joints, NSJ: number of swollen joints, MS: morning stiffness, GPA: global patient assessment, VAS: visual analogic scale, HAQ: health assessment questionnaire, DAS28: Disease Activity Score, CRP: C-reactive protein.

All patients were taking level 1 analgesics such as paracetamol. Thirty-four percent as a daily use. Thirty-four patients (69%) were taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) among them 41% as a daily use. Diclofenac was the most commonly used drug (56%), followed by indomethacin (29.5%) and naproxen sodium (9%). As for corticosteroid therapy, more than half (28 cases: 57%) of the patients were taking oral corticosteroids with a mean dosage of 6.69±2.4mg/d (extremes ranging from 2.5mg/d to 10mg/d).

Drug modifying activity of rheumatic disease was administered in 98% of cases (48 patients). Thirty-four patients were receiving Methotrexate at an average dose of 16.42mg/week±2.92. Nine patients were receiving Salazopyrine at an average dose of 2g/d±0.5. Two patients were on anti-TNF Alpha (1 Etanercept and 1 Certolizumab), two patients on Tocilizumab and three patients were on Rituximab. The remaining patient was on oral corticosteroid therapy and discontinued DMARDs for digestive intolerance. A combination of several disease-modifying treatments was prescribed for four patients. Good compliance was noted in 76% of cases (37 patients) compared with 24% (12 patients) who reported discontinuation of DMARDs therapy. These discontinuations were episodic due to the unavailability of treatment at local clinics.

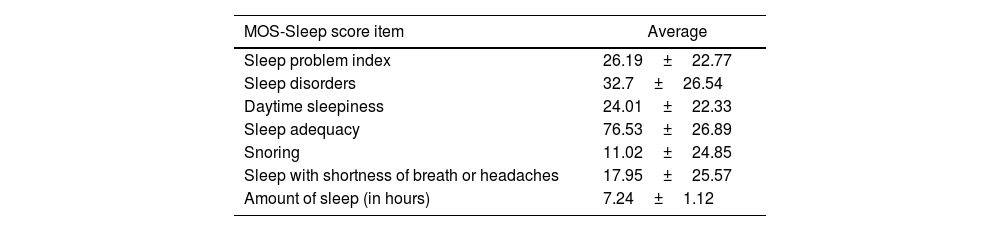

Sleep qualityThe sleep quality assessments in our patients are detailed in Table 3.

Sleep quality assessment results in our population.

| MOS-Sleep score item | Average |

|---|---|

| Sleep problem index | 26.19±22.77 |

| Sleep disorders | 32.7±26.54 |

| Daytime sleepiness | 24.01±22.33 |

| Sleep adequacy | 76.53±26.89 |

| Snoring | 11.02±24.85 |

| Sleep with shortness of breath or headaches | 17.95±25.57 |

| Amount of sleep (in hours) | 7.24±1.12 |

Anxiety was possible in 12% of cases and probable in another 12%. Depression was possible in 11% of cases and probable in 18%.

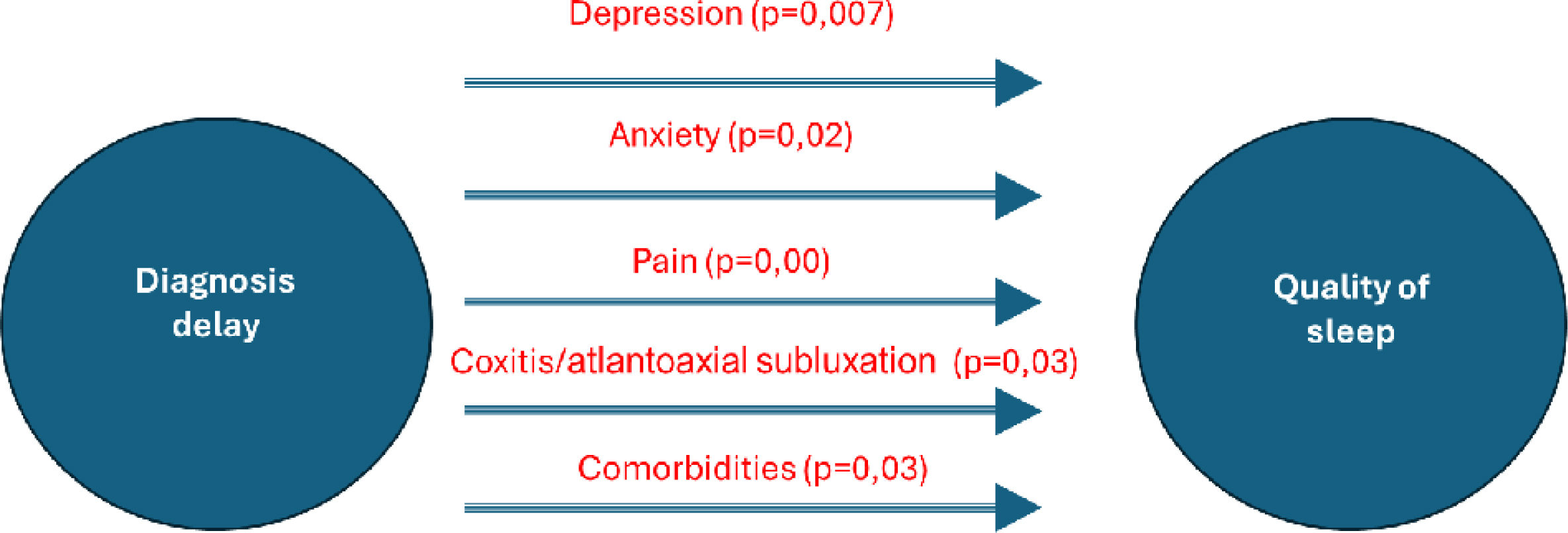

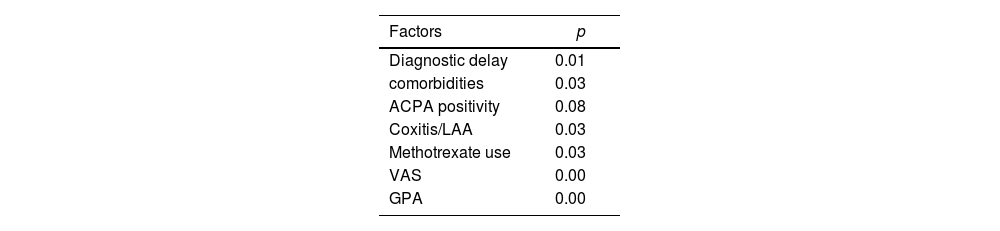

Analytic studyThere was no significant association between duration of RA and sleep quality (p>0.05). Longer diagnostic delay was associated with higher sleep problem index (Table 4) (p=0.01, r=0.351). There was no significant association between NTJ, NSJ and sleep disturbance scores, but a significant positive association was found between VAS pain and all sleep disturbance scores (p=0.00 and r=0.518). RF or ACPA positivity was also not associated with impaired sleep quality (p>0.05). On the other hand, the presence of comorbidities was associated with a higher index (p=0.03). This was also true in the presence of coxitis and/or atlantoaxial subluxation (p=0.03). A significant association was observed between delayed diagnosis and HAD Anxiety (p=0.02). Similarly, a noteworthy correlation was found between delayed diagnosis and HAD Depression (p=0.007). For therapeutic management, we did not find a statistically significant association between the use of NSAIDs or corticosteroids and the index of sleep problems. There was no statistically significant association with the methotrexate (MTX) use. However, the weekly dosage of MTX was positively correlated with the sleep problem index (p=0.03, r=0.358).

On multivariate analysis, Global patient assessment (GPA) (p=0.000), presence of comorbidities (p=0.007), and presence of atlantoaxial subluxation and/or coxitis (p=0.05), were significant factors influencing sleep quality.

DiscussionIn this study, we based the assessment of sleep quality on a validated scale (MOS-Sleep scale) [9,10]. The parameters were studied in a comprehensive and detailed way, the faithful translation of the items and the questioning of the patients by the same examiner allowed to have homogeneous results and to reduce the bias in the interpretation. Nevertheless, our study has some shortcomings and limitations: (a) The small sample size due to the difficulty of recruiting patients and the monocentric nature of the study which constitutes a selection bias. (b) Most of our patients had a low level of education, making it difficult to assess them with a self-questionnaire, which could lead to errors and bias in the interpretation.

The Outcome Measures in Rheumatology working group (OMERACT) have identified sleep as one of the key parameters to be assessed during RA [11]. Poor sleep and reduced total sleep time are common complaints among people with RA. It can in turn lead to deterioration in function, reduce activity levels, and impact mental health [11]. Several measurement instruments have been developed. The MOS-Sleep Scale is a multidimensional measurement tool developed in 1992 [9]. The Arabic version of the MOS-Sleep Scale was developed and validated in 2018 by a Lebanese team [10]. Studies have shown that 70% of RA patients suffer from sleep problems, ranging from difficulty falling asleep to daytime sleepiness which is linked to pain level [12]. The results of our study agreed with the literature [12,13].

Factors influencing sleep qualityWolfe et al. found that sleep disturbance assessed by the MOS-Sleep Scale was inversely correlated with age and female gender [13], in contrast, our results showed that age was an aggravating factor of sleep disturbance (p=0,05). It could be due to the association with comorbidities or the small simple size of our study.

Dealing with socio-economic factors, a Norwegian study investigated the factors influencing sleep disorders in 986 patients with RA [14]. A negative association was found between educational level and the MOS-Sleep score. These results were discordant with those of our study, which could be explained by socio-cultural factors.

Regarding factors related to RAStudies did not find a relationship between RA duration and sleep problems [12,14–16], which was consistent with the results of our study. In contrast, we observed that diagnostic delay negatively impacted sleep problems. This may be related to the stressful state of patients awaiting a diagnosis, as well as the lack of targeted treatment leading to worsening pain due to treatment delays (the association of delayed diagnosis and HAD Anxiety, p=0.02). An association was also found between delayed diagnosis and HAD depression (p=0.007), primarily attributed to pain. Additionally, Austad et al. found that sleep problems were associated with the presence of comorbidities [14], aligning with the results of our study. Specifically, conditions such as coxitis or atlanto-axial dislocation interfere with sleep due to pain and functional limitations. These complications are exacerbated by delayed diagnosis and the subsequent structural progression. Fig. 1 displays the associations identified between delayed diagnosis and its relationship with sleep quality. Dealing with the disease activity; Visual Analogic scale (VAS) pain was the only parameter associated with the different indices assessed by the MOS-Sleep Scale In an Austrian study [12], which was not the case for the NTJ, the NSJ and the Health assessment questionnaire (HAQ). The same findings were demonstrated by Wolfe et al. [13], which was consistent with the results of our study. The impact of pain on sleep quality could be related to nocturnal awakenings caused by RA. Wolfe et al. [13], found a positive association between Global Patient Assessment (GPA) and sleep problems. These results were consistent with our study. Indeed, we found that GPA was an independent factor for worsening sleep problems. This parameter probably expresses the global discomfort felt by the patient in daily life and therefore includes sleep. No association was found between C-Reactive protein level and sleep quality indices, which was consistent with several studies reported in the literature [17–19]. High DAS28 scores were also associated with sleep disturbance [15], which is in line with our results. For immunological status, Guo et al. did not find an association between rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti citrullinated peptides antibodies (ACPA) positivity and sleep disturbance [15]. This was consistent with the results of our study. For RA treatment, Wells et al studied the impact of TNFi on sleep quality assessed by the MOS-Sleep Scale in 433 RA patients treated with Abatercept [20]. They observed a better improvement of sleep parameters with TNFi compared to MTX. We cannot compare this result with our study due to the non-marketing of Abatercept in our country.

ConclusionOur study found that the diagnostic delay had a negative impact on sleep problems and confirmed that active diseases may affect sleep quality in patients followed for RA. This highlights the importance of early diagnosis and prompt global management, including co-morbidities to reduce the impact on sleep and ensure holistic management of patients followed for RA.

AuthorshipRekik Sonia: writing, review and editing.

Ben Messaoud Faïza: writing, review and editing.

Rahmouni Safa: supervision.

Zouaoui Khaoula: supervision.

Ben Ammar Lobna: writing first draft.

Abbes Maïssa: validation.

Boussaïd Soumaya: validation.

Sahli Hela: validation.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestsNone.

None.