Optic neuritis secondary to systemic lupus erythematosus is a rare manifestation with a prevalence of 1%. The case described concerns a patient who presented with optic neuritis associated with SLE. She was 19 weeks pregnant, and required pulses with methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide, which are within the category D drugs used during pregnancy. Three weeks later, she presented with uterine activity, and went into labor, with a fetus of 22 weeks gestation and weighing 430g being obtained, which died 48h later. In medical practice there are ethical guidelines and economic obstacles to carrying out diagnostic and therapeutic protocols established by limiting clinical practice.

La neuritis óptica secundaria a lupus eritematoso sistémico es una rara manifestación con una prevalencia del 1%. Presentamos el caso de una paciente que mostró neuritis óptica asociada a lupus eritematoso sistémico, con 19 semanas de gestación, requiriendo de pulsos de metilprednisolona y ciclofosfamida, que se encuentran dentro de los medicamentos categoría D utilizados durante el embarazo. Tres semanas después presentó actividad uterina y posteriormente trabajo de parto obteniéndose un producto de 22 semanas de gestación y 430g, falleciendo a las 48h. En la práctica médica existen lineamientos éticos y obstáculos económicos que limitan la realización de protocolos diagnósticos y terapéuticos establecidos, limitando la práctica clínica.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease of unknown cause that affects primarily women in fertile age, so it is not unusual to find pregnant women with SLE and its many complications.1 Cyclophosphamide (CTX) is situated in category D of the “Food and Drug Administration” (FDA for its acronym in English) of drugs used during pregnancy, meaning, embryos or fetuses of mothers who require the use of the drug tend to have an adverse outcome.2 We showed the case of a pregnant patient who presented neurolupus, for which required pulse CTX, with the ethical and therapeutic dilemma it represents.

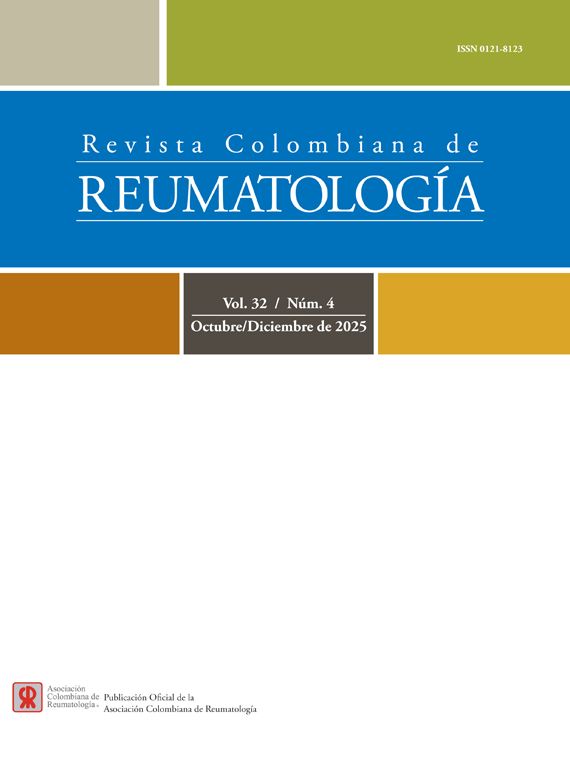

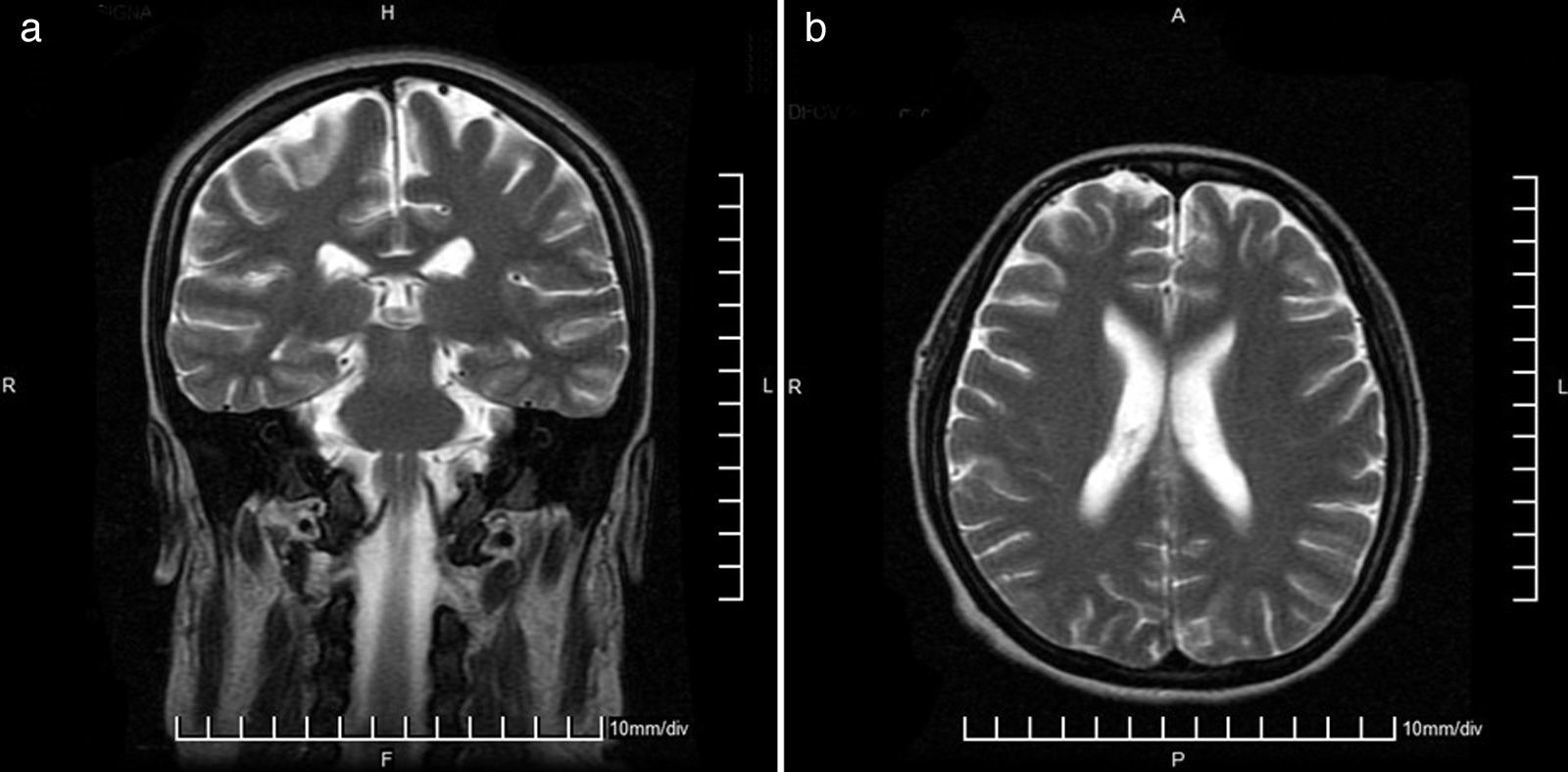

Case presentationWomen, 36 years of age with previous diagnosis of fibromyalgia, with 19 weeks of gestation (WOG) pregnancy, with a history of arthralgia in interphalangeal joints, metacarpophalangeal, carpometacarpal, elbows, knees and ankles of 12 months duration, hair loss and 4 months of evolution was presented. She was admitted into the outpatient clinic for presenting pain in the left eyeball, which intensified with movements, and progressive visual loss to amaurosis. Later, she developed pain in the right eyeball and sudden amaurosis, so she was sent to the rheumatology. Paraclinical were requested, which reported: hemoglobin, 8g/dL; hematocrit, 24.3%; lymphocytes, 0.9 103/μL, antinuclear antibodies (ANA), 28.3IU/ml (normal 0–20IU/mL; positive titration); creatinine 1.98mg/dL; urea nitrogen, 32mg/dL; urinalysis with sediment and active protein 66.4mg/dL. A physical examination revealed visual acuity less than 0.05 in the right eye fundus papilledema, erasing from all temporary sector subretinal hemorrhage and macular edema was observed; left eye with macular edema and subretinal hemorrhage and in the macula (Fig. 1A and B). It was qualified as LES (anemia, lymphopenia, alopecia, optic neuritis, ANA positive and synovitis).

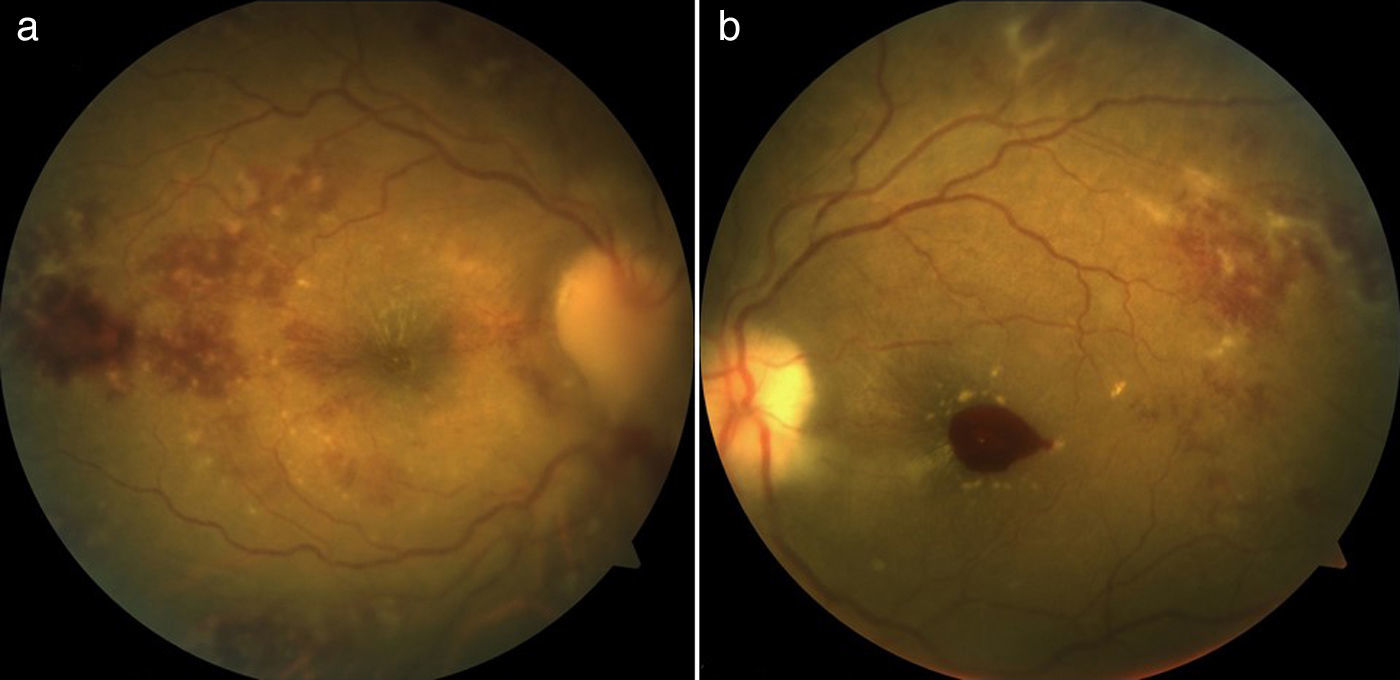

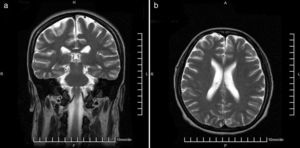

She entered the service of Internal Medicine, in conjunction with management gynecology, who considered that there was a proper course of pregnancy. Cranial MRI was performed to rule out multiple sclerosis, which was normal (Fig. 2). Due to the presence of optic neuritis, it was told the patient the need to administer drugs with a risk teratogenic effects; also were communicated to the patient and family the possible effects, who accepted the administration of CTX. The case was brought under the medical ethics committee at which it was decided not to terminate the pregnancy and continue treatment established. Support for the purchase of rituximab was requested, because this drug has fewer teratogenic effects, however, no favorable response was obtained, so that 1g of methylprednisolone was administered intravenously every 24h for 5 days, then 1g of CTX by the same route.

She remained in surveillance for 48h and was discharged with an appointment in a month for the second pulse CTX. Three weeks after the pulse, she was readmitted for present diarrheal stools and abdominal pain. Stool culture and assessment by the department of gynecology were requested, and it was found uterine activity data, which began with tocolytic treatment; however, by not submitting the symptoms she presented labor, in which a product of 22 WOG and 430g of weight was obtained, who required treatment in the neonatal intensive care unit; nevertheless, the baby died 48h.

Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp were isolated in feces and specific treatment was started. The second pulse of CTX was suspended by the presence of infection. Currently she continues with bilateral amaurosis.

DiscussionOptic neuritis, which is part of the neurologic manifestations of SLE, is a rare event, with a prevalence of 1%.3,4 The treatment involves the use of three pulses of methylprednisolone and in resistant cases, CTX, with variable response to this last.5 CTX is included within the category D of the FDA drugs used in pregnancy. In the first trimester can cause exophthalmos in the product, cleft palate, craniosynostosis, blepharophimosis and intrauterine growth retardation, congenital malformations risk of 20%, high rates of abortion and stillbirth.6

Our patient presents lupus nephritis according to the definition of the group SLICC (Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics),7 which made her a candidate to using CTX, because it decreases the progression to the end-stage renal disease, inducing remission and decreases the necessity of dialysis and transplant. Multiple studies have demonstrated the usefulness of CTX in neuropsychiatric lupus secondary to inflammation as is the case of transverse myelitis and optic neuritis.8 Likewise it has been found that monthly intravenous methylprednisolone CTX is higher for patients with SLE and seizures, peripheral neuropathy and optical neuritis refractory.9 The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommend in patients with neuropsychiatric SLE that reflect an inflammatory or neurotoxic process (aseptic meningitis, optic neuritis, transverse myelitis, peripheral neuropathy, refractory seizures, psychosis, confusional state) and in the presence of lupus activity, use glucocorticoids combined with immunosuppressants (azathioprine or CTX). And with fewer efficacies it could be employed plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulin and rituximab.10 It has been observed better prognosis in patients with SLE and optic neuritis handling after three to five methylprednisolone pulses, followed by a pulse of CTX. Although in most clinical trials the use of CTX is recommended in refractory cases, defined as a lack of improvement in visual acuity after three weeks from the start of treatment with glucocorticoids, in our patient was considered the use of methylprednisolone pulses followed by CTX because she had lupus nephritis, optic neuritis and hematological disorders. Even though azathioprine is a safe drug for use during pregnancy, due to the fetal liver lacks the Inosinate-pyrophosphorylase enzyme, which converts azathioprine to its active metabolite, its effectiveness in optic neuritis is low, and the indication is only as glucocorticoid sparing therapy.11

With regard to the use of immunoglobulin it was found that does not reduce the number of relapses, not restore visual function or improves preservation of the optic nerve in patients with optic neuritis.12

Because our patient was in the 19th week of pregnancy, there was the dilemma on the use of CTX; it was proposed the use of rituximab, a drug that is in category C of the FDA, with which there have been reports of transitory lymphopenia and depletion of B cells in children of mothers exposed.13 It has been observed that rituximab can be as effective as CTX to control severe manifestations of SLE; experience in neurolupus is scarce, merely case series, in which improvement has been found in up to 70%.14 It can be used in patients with diffuse forms of neurolupus, cognitive deficits, psychosis and seizures. However, the patient did not have the economic resources to purchase the drug, since it is not provided by the medical unit.

In pregnant women with SLE it must be make determinations of anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies, to establish the risk of congenital heart block, which is 2% in mothers carrying the anti-Ro.15 The presence of antiphospholipid antibodies is associated with increased risk of preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome and the pattern of hypocomplementemia (C3, C4 or CH50) has been associated with disease activity and adverse outcomes of pregnancy.2 Ideally, a pregnant patient LES carrier should have anti DNA antibodies of double stranded, levels of C3, C4 and CH50, lupus anticoagulant as well as anticardiolipin antibodies, anti-β2-glycoprotein I, anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB. However, the economic limitations may be an impediment to evaluate the prognosis and perform surveillance of the disease in this group of patients.

The patient received a multidisciplinary management by neurology department to discard data of neuromyelitis optica or multiple sclerosis, so cranial MRI was performed. She received management by rheumatology however because she did not have the economic possibilities, she could not complete the study protocol with the corresponding antibodies (anti-DNA antibodies of double stranded, levels of C3, C4 and CH50, lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibodies, anti-β2-glycoprotein I, anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB.). She received attention from the nephrology department who consider the need for use of CTX, and management of obstetrics and pediatrics for fetal surveillance.

In the case of our patient, the high probability of death for both mother and fetus, forcing authorities to session A case before the ethics committee of the Hospital.

The use of CTX was decided, despite the risk, once the patient treatment options just like the use of glucocorticoids, including pulse and the request of the use of rituximab were exhausted. The patient had a torpid evolution of pregnancy, so discontinuation was necessary. She was given the benefit of the neonatal intensive care newborn, however, he died days later. Moreover, the mother failed to restore vision, which could be related with prolonged decision making related to the ethical dilemma posed a therapeutic decision.

Unfortunately there are no clinical practice guidelines to bring the proper management of a pregnant patient with optic neuritis, especially when presents other data of disease activity. Recently the EULAR16 published a guide about issues to consider for the use of antirheumatic published drugs before and during pregnancy and lactation, which refers only in severe and refractory disease the use of methylprednisolone, intravenous immunoglobulin or even CTX should be considered, classifying it as a grade of recommendation D.

ConclusionsIn medical practice there are both ethical guidelines, and economic obstacles to carrying out diagnostic and therapeutic protocols established. There are few therapeutic alternatives when the clinician is faced with bioethical dilemmas as in the case of our patient, since the possibility of morbidity and mortality in the binomial is wide. One of the limitations that still have the social security in Mexico is economic resource, which undoubtedly represents a sensitive issue that has not been dealt clearly in our country.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.