The case involves a 16-year-old boy from Iran with various medical issues. He experiences morning pain in his knees, ankles, and limb deformity. His medical history revealed congenital deafness and a previous episode of fever and seizures. The boy's parents are related, and his 6-month-old sister, who had similar symptoms, passed away. Physical examination findings include short stature, shortened limbs, flexion contracture in the elbow joints, abnormalities such as enlarged knees and ankles, Pectus excavatum, short arms, protruding eyes, a flattened nose bridge, and finger deformities. X-ray results show enlarged joints, decreased thoracic vertebrae height, thoracic spine scoliosis, and thickened and fused wrist bones. Echocardiography and eye examination showed normal findings with no abnormalities, but audiometry revealed bilateral sensorineural hearing loss. Genetic testing confirmed a homozygous mutation in the COL11A2 gene, leading to a diagnosis of OSMED.

El caso involucra a un niño de 16 años de Irán con varios problemas médicos. Experimenta dolor matutino en las rodillas y en los tobillos y presenta deformidades en las extremidades. Su historial médico revela sordera congénita y un episodio previo de fiebre y convulsiones. Los padres del niño son parientes y su hermana de 6 meses, que tenía síntomas similares, falleció. Los hallazgos del examen físico incluyen baja estatura, extremidades acortadas, contractura en flexión de las articulaciones del codo y varias anomalías como rodillas y tobillos agrandados, depresión del esternón, brazos cortos, ojos prominentes, puente nasal aplanado y deformidades en los dedos. Los resultados de la radiografía muestran articulaciones agrandadas, disminución de la altura de las vértebras torácicas, escoliosis de la columna torácica y huesos de la muñeca engrosados y fusionados. El ecocardiograma y el examen ocular fueron normales, pero la audiometría reveló pérdida auditiva neurosensorial bilateral. Las pruebas genéticas confirmaron una mutación homocigota en el gen COL11A2, lo que llevó a un diagnóstico de displasia otospondilomegaepifisaria (OSMED).

The COL11A2 gene mutations that cause otospondylomegaepiphyseal dysplasia (OSMED), also known as Weissenbacher–Zweymüller syndrome, are autosomal recessive disorders. It is a relatively rare condition, with fewer than 100 cases reported in the medical literature. OSMED affects skeletal development, hearing, and the craniofacial region [1]. Early diagnosis and intervention are crucial for the optimal management of affected individuals. OSMED disorder affects the skeletal and sensory structures in the body. It falls under the broader category of skeletal dysplasias, a condition characterized by abnormal bone and cartilage development [2]. Distinct skeletal abnormalities predominantly define OSMED. These include shortened limbs, abnormal spinal curvature (scoliosis), and deformities in specific bones, such as the long bones of the arms and legs. Additionally, bone growth and maturation are often delayed, further contributing to the characteristic features of this condition. OSMED affects the bones’ growth plates, which cause bone elongation during childhood and adolescence. In OSMED, the growth plates may be irregularly shaped, leading to shorter stature [3]. OSMED is associated with sensorineural hearing loss caused by abnormalities in the inner ear structures or the auditory nerve. Hearing loss severity can vary among affected individuals, ranging from mild to profound. Some OSMED patients may also have eye abnormalities, such as myopia (nearsightedness), cataracts, and retinal detachment. These ocular issues can contribute to visual impairment [4]. OSMED results from mutations in the COL11A2 gene, which makes the type XI collagen protein. This collagen is essential for developing and maintaining various tissues, including cartilage, bone, and the inner ear [5]. OSMED management typically involves a multidisciplinary approach, treating specific symptoms and complications. This may include interventions such as hearing aids or cochlear implants for hearing loss, orthopedic management for skeletal abnormalities, and regular monitoring of ocular health [3].

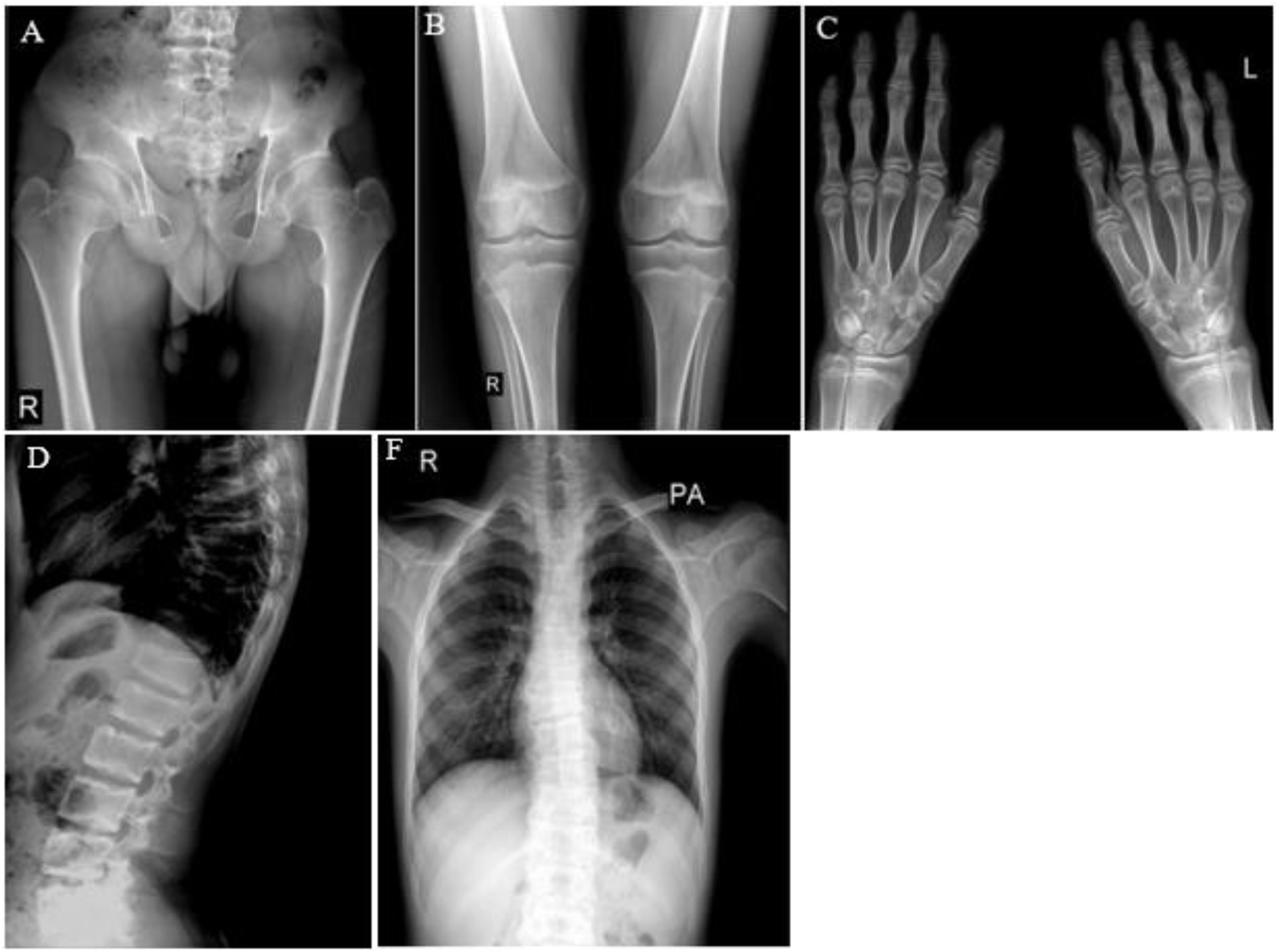

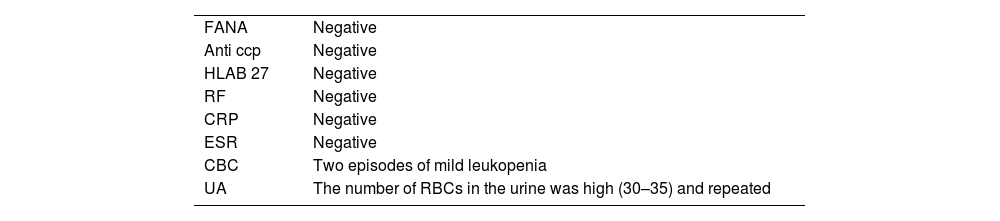

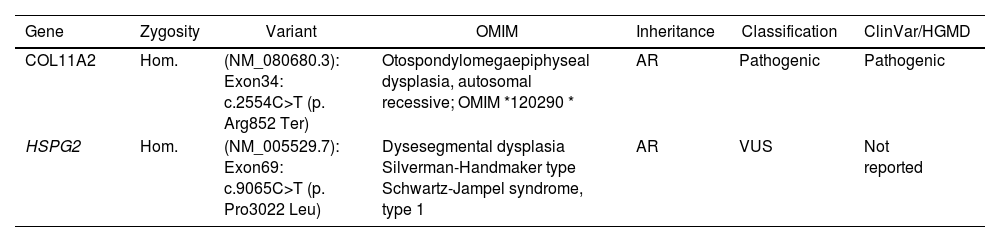

Case presentationOur case involves a 16-year-old boy residing in the Khuzestan province of Iran who presented with morning pain in his knees, ankles, and limb deformity. The patient's medical history reveals congenital deafness, which is not observed in the parents, along with a past episode of fever and seizures. Upon examining the family history, the parents were related. Sadly, the patient's 6-month-old sister, who had the same condition, passed away. During the physical examination, several abnormalities were observed (Fig. 1). The patient exhibited short height, shortened limbs, and flexion contracture in the elbow joints. X-ray images revealed enlarged knees and ankles, a slight depression in the sternum (Pectus excavatum), enlarged joints, short arms, protruding eyes, and a flattened nose bridge. Proximal interphalangeal (PIP) flexion contracture was also noted in both hands’ fingers 3, 4, and 5 (Fig. 2). Evaluation of the bones revealed decreased thoracic vertebrae height, accompanied by thoracic spine scoliosis. Furthermore, the wrist bones exhibited increased thickness and density, while the boundaries of some wrist bones appeared unclear, suggesting possible fusion. Echocardiogram results were typical, and no significant issues were detected during the eye examination. Audiometry revealed bilateral sensorineural hearing loss. Table 1 summarizes the test results. Genetic testing confirmed a homozygous mutation in the COL11A2 gene, consistent with an OSMED diagnosis (Table 2).

X-ray of patient. (A, B) Enlarged joints. (C) An increase in the thickness and density of the wrist bones and the uncertain limits of some wrist bones, which raises the possibility of some bones sticking together. (D, F) A pronounced decrease in the height of the thoracic vertebrae is accompanied by the presence of scoliosis in the thoracic spine.

Molecular analysis of exome sequencing.

| Gene | Zygosity | Variant | OMIM | Inheritance | Classification | ClinVar/HGMD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COL11A2 | Hom. | (NM_080680.3): Exon34: c.2554C>T (p. Arg852 Ter) | Otospondylomegaepiphyseal dysplasia, autosomal recessive; OMIM *120290 * | AR | Pathogenic | Pathogenic |

| HSPG2 | Hom. | (NM_005529.7): Exon69: c.9065C>T (p. Pro3022 Leu) | Dysesegmental dysplasia Silverman-Handmaker type Schwartz-Jampel syndrome, type 1 | AR | VUS | Not reported |

OSMED is characterized by a wide range of clinical features, including disproportionately short stature, joint hypermobility, and epiphyseal dysplasia. OSMED hearing loss is typically bilateral and sensorineural. Radiographic findings often demonstrate abnormalities in the epiphyses, with irregularities and flattening observed. Genetic testing is crucial for confirming the diagnosis; mutation analysis of the COL11A2 gene is the gold standard. OSMED is a rare genetic disorder that affects skeletal development, hearing, and vision. While there may be other conditions with overlapping symptoms, it is critical to consult with a medical professional for an accurate diagnosis [6].

OSMED and related skeletal disorders: clinical similarities and diagnostic differencesStickler syndrome type 3, Werner syndrome (WZS), and non-allelic multiple sclerosis (MS) are some of the diseases that OSMED is similar to in terms of phenotype. These diseases also have a range of clinical severity and inheritance models. Alleles of OSMED, Stickler type 3, and WZS are often linked to disfigurement and skeletal radiological issues that don’t appear in the eyes (like high myopia, vitreoretinal degeneration, and retinal detachment). On the other hand, non-allelic MS and) Kniest dysplasia (KD are associated with ocular symptoms. People with OSMED, Stickler syndrome type 3, and WZS have different homozygous or heterozygous mutations in the COL11A2 gene on human chromosome 6p21.3. This gene codes for collagen type 11, alpha two proteins. Given these facts, the theory that most adequately explains the typical ophthalmologic observations is that the vitreous body does not express COL11A2 [7]. WZS and OSMED syndrome are similar. WZS is diagnosed by its main symptoms, which include eyes that stick out, micrognathia, cleft palate, depressed nasal root, hypertelorism, and an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern with short limbs at birth. Cervical coronal clefts, bulbous deformities of the ischial and pubic bones, broad iliac wings, expanded epiphyses, and dumbbell broadening of the long bone metaphyses, particularly the femurs and humeri, are among the radiological findings. WZS also includes enlarged epiphyses. Normal adult height with catch-up growth after two or three years of age, which is absent in OSMED syndrome, is the defining characteristic of WZS. Stickler syndrome type 1 has distinctive facial characteristics and hearing loss in allelic Stickler syndrome type 3. Some patients had moderate arthropathy or a cleft palate but lacked ocular symptoms. Clinical researchers maintain that these three illnesses are unique and independent entities. Some people think that the three represent the severity range of one disorder. According to some researchers, the terms heterozygous OSMED (which includes autosomal dominant traits like WZS and Stickler syndrome type 3) and homozygous OSMED (which includes autosomal recessive cases of OSMED) should be used interchangeably [8–10]. The clinical overlap and differential diagnosis of non-ocular Stickler syndrome (type II), WZS, and OSMED have been the subject of ongoing discussion [9–11]. It was thought that the nose in Stickler syndrome did not remain remarkably short, whereas autosomal dominant OSMED seemed to do so [11]. Furthermore, OSMED syndrome is supported by the absence of severe myopia and joint hypermobility in later infancy and childhood [11]. Furthermore, allelic variants may be represented by autosomal dominant OSMED and non-ocular Stickler syndrome (type II), according to Pihlajamaa et al [9]. It has been determined what the WZS phenotype with autosomal dominant OSMED is. However, the phenotypes of WZS and recessive OSMED syndromes are still difficult to distinguish. A substantial family with rhizomelic dwarfism, cleft palate, sensorineural deafness, metaphyseal and vertebral abnormalities, refractive errors, and strabismus was described by Rabinowitz et al [12]. Following that, these patients accelerated their growth, meeting WZS requirements. The scientists classified these patients as having recessive WZS as a result. Moreover, homozygosity for the COL11A2 gene was revealed by mutation analysis in these patients [10]. Whether autosomal recessive OSMED and WZS are the same is a question. We believe that follow-up investigations for OSMED patients are strongly advised. Stickler syndrome is a connective tissue illness affecting the skeleton, inner ear, eye, head, and face. It affects the ends of bones in joints and the vitreous humor in the eyeball. There are four forms of Stickler syndrome: three are clearly distinguished from one another, while the fourth is poorly known. Like OSMED, this illness results in abnormalities of the eyes, ears, and joints, hearing loss, visual issues, and skeletal abnormalities [13,14]. Kniest dysplasia is dwarfism, which resembles OSMED because it causes joint issues, skeletal deformities, and small height. The COL2A1 gene mutation causes skeletal dysplasias and aberrant skeletal growth. The indications and manifestations of congenital spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia, Marshall syndrome, and KD are comparable to those of OSMED [15]. Autosomal-dominant hereditary MS and KD share phenotypic similarities, including sensorineural hearing loss, small height, and facial features such as micrognathia, large philtrum, and flat midface. The presence of restricted movement in the metacarpophalangeal joints and/or a higher degree of involvement of the vertebral bodies is another characteristic that sets MS apart [16]. The lengthy bone abnormalities resemble those of OSMED syndrome, which is most likely not a distinct condition from MS. In addition, KD patients have significant spinal abnormalities and extremely low stature, which are less evident in OSMED. Since OSMED is a sporadic illness, diagnosing it is a crucial clinical step in ensuring patients develop normally. A hereditary condition known as sepondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenita (SEDC) affects bone growth and development, leading to visual and hearing difficulties. The most prevalent dwarfism type is achondroplasia, which results in malformed bones, a big head, and short limb [17]. A genetic illness called osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is characterized by brittle bones. Certain subtypes of OI have skeletal abnormalities and hearing loss, which may overlap with OSMED [18]. These illnesses can be helpful when it comes to treatment and differential diagnosis. Cartilage biopsies from patients with OSMED and osteoarthritis were compared; the loss of normal cartilage architecture would impede this process and impact joint surfaces and bone lengths [5]. According to electron microscopy, patients with OSMED had larger collagen fiber sizes and aggregates, which were not observed in primary osteoarthritis. It is unlikely that the collagen XI molecule will absorb the shortened protein poorly. This will result in the absence or malfunction of collagen fibrils. Collagen XI most likely preserves the organization and architecture of collagen fibrils and restricts the diameter of collagen II and IX fibrils in cartilage [5,8]. Aberrant fibrils could cause OSMED and epiphyseal dysplasia. Alterations may influence early-adult osteoarthritis in joint cartilage structure and disturbances of epiphyseal architecture. These impacts on bone alignment and joint shape should be carefully considered during surgical planning. OSMED and Marshall Syndrome are extremely similar. Given these phenotypic similarities and the strong correlation between the COL11A1 and COL11A2 gene products, we suggest that a COL11A1 mutation could be the etiology of Marshall Syndrome. Numerous other disorders could result from changes in collagen XI genes [5]. Several skeletal problems, such as those in the spinal column and the proximal epiphysis of the long bone, are included in the diverse group of diseases called spondylo-epiphyseal dysplasia (SED). It is linked to several craniofacial abnormalities, ocular diseases, and, infrequently, OSMED-deafness. When it does occur, type II collagen in the inner ear—whose production is changed in “OSMED”—may help to explain why hearing loss is mostly neurosensorial. On the other hand, patients with inner ear and articulation diseases, including sudden hearing loss, have antibodies against type II collagen. These latter disorders exhibit these antibodies and offer a favorable prognostic score even with immunosuppressive treatment [6].

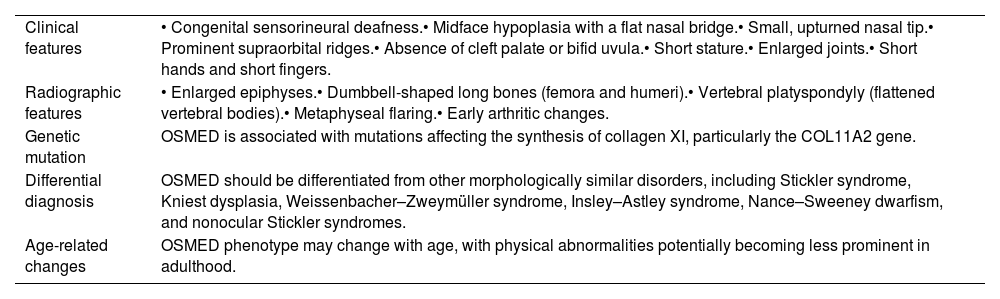

The diagnosis of OSMED typically involves a combination of clinical evaluation, medical history assessment, and various diagnostic tests (Table 3).

The criteria for the diagnosis of Oto-Spondylo-Megaepiphyseal dysplasia.

| Clinical features | • Congenital sensorineural deafness.• Midface hypoplasia with a flat nasal bridge.• Small, upturned nasal tip.• Prominent supraorbital ridges.• Absence of cleft palate or bifid uvula.• Short stature.• Enlarged joints.• Short hands and short fingers. |

| Radiographic features | • Enlarged epiphyses.• Dumbbell-shaped long bones (femora and humeri).• Vertebral platyspondyly (flattened vertebral bodies).• Metaphyseal flaring.• Early arthritic changes. |

| Genetic mutation | OSMED is associated with mutations affecting the synthesis of collagen XI, particularly the COL11A2 gene. |

| Differential diagnosis | OSMED should be differentiated from other morphologically similar disorders, including Stickler syndrome, Kniest dysplasia, Weissenbacher–Zweymüller syndrome, Insley–Astley syndrome, Nance–Sweeney dwarfism, and nonocular Stickler syndromes. |

| Age-related changes | OSMED phenotype may change with age, with physical abnormalities potentially becoming less prominent in adulthood. |

These criteria comprehensively describe the clinical and radiographic features used to diagnose OSMED and distinguish it from similar disorders. Genetic testing is often necessary to confirm the diagnosis, as mutations in the COL11A2 gene are a key characteristic of OSMED.

Clinical evaluation and diagnostic characteristics of OSMEDClinical evaluations are comprehensive physical examinations of the patient, emphasizing their facial features, skeletal structure, and vision or hearing impairment indications. A thorough medical history is necessary to detect patterns of bone deformities, hearing loss, or visual issues [2,19]. DNA sequencing is one type of genetic testing that can confirm an OSMED diagnosis and distinguish it from comparable disorders. Imaging tests, like CT and X-rays, can give specific details about bone composition and growth. Determining the kind and extent of hearing loss requires an audiological evaluation that includes speech and pure-tone audiometry. Ophthalmological tests can also be carried out to assess visual acuities and eye anatomy, such as myopia and retinal abnormalities [19]. Our patient's radiographic and clinical results are consistent with OSMED features frequently described in the literature (Table 2). Minor differences in OSMED manifestations have been documented; these differences most likely stem from gene mutations’ varying types and locations [3,11,20]. It is exceedingly difficult to characterize a “typical” manifestation of OSMED or comparable illnesses because there are so few people with them. It is important to remember that OSMED is a dynamic condition in which the patient's phenotype varies with age. Physical abnormalities are traditionally considered more noticeable in childhood and subside with age. However, our long-term follow-up indicates that OSMED patients’ hearing loss and skeletal characteristics worsen over time [3,11,21]. More severe conditions may present earlier, contributing to the previously observed fluctuation in physical findings with age. Ascertainment bias might be the cause of this. Endochondral ossification forms in the long bones, bony hard palate, and various facial bones, including the mandible and nasal septum [22]. This process forms cartilaginous growth plates, which give bones their length and shape [23]. Radiographic signs of epiphyseal and vertebral dysplasia, metaphyseal flaring, early arthritic change, and mid-face hypoplasia, along with phenotypic signs like a bulbous, upturned nose, limbs that don’t fit together right, and sensorineural hearing loss, should make you think of OSMED. Prelingual development of sensorineural hearing loss, growth of the epiphyses with widespread limb shortening, and vertebral body dysplasia are characteristics of OSMED [3,24,25]. Define characteristics of the face, such as mid-face hypoplasia and an upturned nose with a depressed nasal bridge [1,24,26]. While not present in every case, cleft palate, micrognathia, and a short nose are prevalent [3,9,26]. Radiography shows the condition affects several joints. Typical findings include massive epiphyses and metaphyseal flare, resulting in a dumbbell-shaped shortening of the long bones of the upper and lower extremities [1–3]. Flattened vertebral bodies (platyspondyly) result from coronal clefts with faulty ossification inside the vertebral bodies of the spine [1,2]. Despite having shorter stature as children, most patients grow to almost typical height [11]. Growing older causes skeletal defects to lessen, although patients typically experience joint discomfort; arthritic changes are common [3,5,11].

Genetic basis and clinical implications of OSMEDEarly intervention requires constant surveillance and early recognition. Genetic testing is appropriate for precise genetic risk counseling, diagnosis confirmation, and elucidation of expected comorbidities. An extremely rare skeletal dysplasia known as OSMED (Mendelian Inheritance in Man #215150) is caused by autosomal recessive or dominant negative mutations that impair the production of collagen XI in otospondylomegaepiphyseal dysplasia [5,8]. Three proteins make up the heterotrimer known as collagen XI: a1(XI) from chromosome 1, a2(XI) from chromosome 6, and a1(II) from chromosome 12 (also known as a3(XI)) [11]. On chromosome 6, the COL11A2 gene codes for the a2 (XI) protein [8]. Collagen II, IX, and the collagen XI heterotrimer copolymerize to generate the inner ear's collagen and hyline cartilage [1,11]. The tympanic membrane also contains type XI collagen [27] and intervertebral discs [1], as well as many other nutrients that are crucial to skeletal growth [28]. Therefore, disorders in these organs are likely to result from COL11A2 gene mutations. It's possible that Insley and Astley's 1973 OSMED report was the first accurate one [24], even though Giedion et al. The term was not coined until 1982 [26]. In 1995, the first COL11A2 gene mutation that caused OSMED was found to be causal [8]. Fourteen other causal mutations have been found since then. Because OSMED clinical overlaps with Stickler types 1 and 2, Kniest dysplasia, Weissenbacher–Zweymüller, Insley–Atley, Nance–Sweeney dwarfism, and nonocular Stickler syndromes, identifying the causal gene helped clear up the nosologic uncertainty reported in early case reports [11]. The COL11A2 gene produces type XI collagen, a crucial component of connective tissues; mutations in this gene result in OSMED. These mutations disrupt type XI collagen's typical structure and function, resulting in distinctive trait [1,25,29]. Non-syndromic hearing loss is caused by heterozygous COL11A2 mutations [30]. A family with autosomal dominant nonocular Stickler syndrome syndromic hearing loss [20,31] was found to have homozygous mutations in a family suffering from autosomal recessive non-syndromic hearing loss. The discovery was explained by scientists as the result of a process known as nonsense-associated altered splicing [20,31]. So, transcription mutations can change the non-sense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) and NAS pathways. It was hypothesized that COL11A2 gene mutations result in autosomal recessive OSMED syndrome in the homozygous condition. In contrast, haploinsufficiency and no disease manifestations occur in the heterozygous state. Each affected person's level of OSMED fluctuates. Skeletal abnormalities, joint issues, sensorineural hearing loss, and visual issues such as myopia and retinal abnormalities are among the symptoms. Genetic testing, including DNA sequencing, can confirm the diagnosis and pinpoint the precise mutations causing OSMED. Genetic counseling may also help affected people and their families understand inheritance patterns and potential hazards for future generations [32].

Management strategies for OSMEDAs of right now, there is no known cure for OSMED, so support and symptom management are the main goals of care. Comprehensive care requires a multidisciplinary approach combining audiologists, otolaryngologists, geneticists, and orthopedic surgeons. Early intervention programs to assist with developmental milestones, cochlear implants or hearing aids for hearing loss, and physical therapy for limb deformities are some examples of treatment techniques. While there isn’t a specific treatment for OSMED, an early diagnosis may aid normal development. This can be accomplished with a coordinated, multidisciplinary approach. Families and affected people may benefit from genetic counseling.

ConclusionOSMED is a rare genetic disorder characterized by skeletal abnormalities, hearing loss, and distinct craniofacial features. Early diagnosis and multidisciplinary approaches are crucial for effective management. This case report highlights the importance of recognizing OSMED clinical manifestations and implementing appropriate interventions to improve the quality of life for affected individuals. Further research is needed to understand the underlying mechanisms of the disease better and explore potential therapeutic options.

Authors’ contributionsM.F. contributed to the rationale and patient management, and all authors contributed to the manuscript development and descriptions.

Ethics approval and consent to participateAll procedures performed in the study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The family of patient had provided written informed consent to publish her case (including publication of images and genetic tests).

Consent for publicationInformed consent was obtained from this patient.

Funding sourcesThere were no funding sources.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Availability of data and materialsThe datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors express their sincere appreciation to their esteemed colleagues at the Clinical Research Development Unit, Golestan Hospital, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran, for their invaluable collaboration and support.