Social distancing measures due to the COVID-19 pandemic prevented many children with neurodevelopmental disorders from accessing face-to-face treatments. Telerehabilitation grew at this time as an alternative therapeutic tool. In this study we analysed remote cognitive rehabilitation in neurodevelopmental disorders.

MethodsThis was a prospective, quasi-experimental (before-after) study that included 22 patients (mean age 9.41 years) with neurodevelopmental disorders who had telerehabilitation for over six months.

ResultsAfter six months of telerehabilitation, a statistically significant improvement was found with a large effect size in these areas: attention (sustained, selective and divided), executive functions (verbal and visual working memory, categorisation, processing speed), visuospatial skills (spatial orientation, perceptual integration, perception, simultanagnosia) and language (comprehensive and expressive). On the Weiss Functional Impairment Scale, all areas (family, learning and school, self-concept, activities of daily living, risk activities) improved with statistical significance. We found a positive correlation between the number of sessions and the improvement observed in executive functions (visual working memory, processing speed), attention (sustained attention, divided attention) and visuospatial skills (spatial orientation, perceptual integration, perception, simultanagnosia). We did not find statistical significance between the family structure and the number of sessions carried out. A high degree of perception of improvement and satisfaction was observed in the parents.

ConclusionsTelerehabilitation is a safe alternative tool which, although it does not replace face-to-face therapy, can achieve significant cognitive and functional improvements in children with neurodevelopmental disorders.

Las medidas de distanciamiento social debidas a la pandemia por COVID-19 impidieron que muchos chicos con trastornos del neurodesarrollo pudieran acceder a tratamientos presenciales. La telerrehabilitación creció en este tiempo como una herramienta terapéutica alternativa. El objetivo es analizar la telerrehabilitación cognitiva en trastornos del neurodesarrollo.

MétodosEn este estudio prospectivo, cuasi-experimental (antes-después), se incluyó a 22 pacientes (media de edad, 9,41 años) con trastornos del neurodesarrollo que realizaron telerrehabilitación con el programa Rehametrics por más de 6 meses.

ResultadosLuego de 6 meses de telerrahabilitación, se constató una mejoría estadísticamente significativa con un gran tamaño del efecto en áreas de: atención (sostenida, selectiva y dividida), funciones ejecutivas (memoria de trabajo verbal y visual, categorización, velocidad de procesamiento), habilidades visuoespaciales (orientación espacial, integración perceptiva, percepción, simultagnosia) y lenguaje (comprensivo y expresivo). En la Escala de Impedimento Funcional de Weiss mejoraron con significancia estadística todas las áreas (familia, aprendizaje y escuela, autoconcepto, actividades de la vida diaria, actividades de riesgo). Se constata una correlación positiva entre la cantidad de sesiones y la mejoría observada en funciones ejecutivas (memoria de trabajo visual, velocidad de procesamiento), atencionales (atención sostenida, atención dividida) y habilidades visuoespaciales (orientación espacial, integración perceptiva, percepción, simultagnosia). No encontramos significancia estadística entre la estructura familiar y la cantidad de sesiones realizadas. Se observó un alto grado de percepción de mejora y satisfacción en los padres.

ConclusionesLa telerrehabilitación puede ser una herramienta alternativa segura que, sin reemplazar la presencialidad, puede lograr mejoras cognitivas y funcionales significativas en niños con trastornos del neurodesarrollo.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is causing a global impact on all aspects of human life. While the world implements strategies to stop the transmission of the virus according to the World Health Organization's recommendations of social distancing and staying at home, these measures are generating significant disruption in the population's routines, especially in children who stopped going to school. Social distancing measures have also prevented many children with neurodevelopmental disorders from accessing their rehabilitation therapies. These children, who usually require special care and benefit from face-to-face treatment, were forced to suspend their in-person therapies and seek alternative and innovative strategies to continue their rehabilitation.1,2

Although telemedicine is not new and already enabled access to health for rural and remote populations, its growth has been exponential during the COVID-19 pandemic, incorporating new practices and developments. Telemedicine is the use of electronic information and telecommunications technologies to support and promote clinical health, health-related vocational training and rehabilitation from diseases. Telemedicine can be synchronous, when communication occurs in real-time, or asynchronous, when the patient or their healthcare professional sends the medical information to be analysed, and the communicated response arrives later.3

One aspect of telemedicine is telerehabilitation, which consists of the provision of distance rehabilitation services through electronic systems based on information and communication technologies (ICT). The development of these technologies allows rehabilitative care to be extended beyond the hospital to a more eco-friendly setting without the need for the patient to travel. Although initially it was families in remote or rural areas who benefited, with the COVID-19 pandemic and the impossibility of maintaining in-person therapies, implementation was extended to a large part of the population.4,5

With regard to the effectiveness of telerehabilitation, several reports in the literature confirm that the results obtained are similar to those achieved by traditional methods, but in the case of telerehabilitation they are obtained at a lower cost, with better quality of life and greater patient satisfaction.6–9 This aspect is important, given that a high degree of satisfaction predicts greater adherence to treatment.10

Although the literature was extensive, the studies published up to the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic essentially included adult patients,11 patients with spinal cord injuries,12 multiple sclerosis,13 anxiety or mood disorders, and treatment of chronic diseases in rural areas.14 There are very few publications on the paediatric population, even though it is considered that, for a large proportion of the world's child and adolescent population, Internet use has become routine and the percentage is expected to further increase over the next 10 years. Publications that did study this segment of the population reported benefits in the use of telerehabilitation for various conditions, such as respiratory diseases in adolescents,15 early intervention for children under two years of age,16 treatment of adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorders17 or multiple sclerosis,18 treatment of executive functioning in adolescents with epilepsy,19 or children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), where computer technology was used for parent training20 alone or in combination with drug treatment.21

Although exponential growth in telemedicine has been seen since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, few studies have analysed its implementation in paediatric subjects with neurodevelopmental disorders who, given the impossibility of face-to-face treatment, might benefit from telerehabilitation. With that in mind, our aim was to study the modality of distance cognitive rehabilitation in this particular population.

MethodsDesignProspective analytical and quasi-experimental study (before-after).

ParticipantsWe included all subjects between 4 and 17 years of age with a diagnosis of a neurodevelopmental disorder who participated for more than six months in the telerehabilitation programme of our hospital's Paediatric Neurology Department during the COVID-19 pandemic from March 2020 to May 2021.

The study participants had the following neurodevelopmental disorders: autism spectrum disorder (ASD); ADHD; intellectual disability (ID); and reading disorder (RD). A child neurologist validated the diagnosis of each participant according to DSM-5 criteria, using data from their medical records, neuropsychological assessment, neurological examination and parent interview. All patients with ASD had positive Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule second version (ADOS-2) and Autism Diagnostic Interview Revised (ADI-R) studies, carried out before inclusion.

Exclusion criteriaParticipants were excluded if they did not complete the assessment scales administered or if they had not accessed the telerehabilitation platform with a regularity of at least twice weekly attendance for at least six months.

We also excluded subjects with a full-scale intelligence quotient (FSIQ) <50, given that their cognitive impairment might interfere with the understanding of the task to be performed, along with those with motor, cognitive or behavioural disorders which made it impossible to use the electronic device (tablet or mouse) and perform the therapeutic exercises, those with no Android tablet or personal computer, those with no internet access to send and receive the activities, and those with incomplete or missing neuropsychological assessments.

Neuropsychological assessmentChildren with ASD completed the ADOS and ADI-R tests before being included in this research. In the ADI-R test, assessments with values above the cut-off point in at least three of the areas assessed by the scale were assigned as positive. In the area of social interaction, the cut-off point was 10; in qualitative abnormalities in communication, 8; in restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped patterns of behaviour, 3; in abnormality of development evident at or before 36 months, 1. In the ADOS test, assessments with total values above the cut-off points were assigned as positive, which varied depending on the module used. In module 1, the cut-off point was 11 when participants had no words, or 8 when subjects had few words. In module 2, the cut-off point was 7 when the participants were under 4 years of age and 11 months or 8 when they were over 5 years of age. In module 3, the cut-off point was 7.

Before the start of telerehabilitation, participants completed a neuropsychological assessment, which included the Weschler Intelligence Scale for Children, version V (WISC-V), in Spanish in those over 7 years of age, or Wechsler Preschool & Primary Scale of Intelligence, version IV (WPPSI-IV), in children under 6 years and 11 months,22 the computerised Conners' Kiddie Continuous Performance Test (K-CPT-2) in children under 7 years and 11 months or CPT-3 in those over 8) and the Weiss functional impairment rating scale.

From the WISC-V, the following primary indices were analysed: verbal comprehension (VCI); fluid reasoning (FRI); working memory (WMI); processing speed (PSI); and full-scale intelligence quotient (FSIQ).22 A standard score with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15 was applied for analysis.

The Conners' Continuous Performance Test 3rd edition (CPT-3) (2014) is a revision of its predecessor, the CPT-2 (2000), designed for subjects over 8 years of age to assess attention-related problems in four domains of attention. The subject sits in front of the computer screen and is asked to respond by pressing the space bar every time a letter other than X appears on the screen (Non-X paradigm). In this version, the background is white and the letters are black. There are 360 stimuli (letters) with intervals of 1, 2 or 4 s, divided into 6 blocks, in turn divided into 3 sub-blocks each, with 20 stimuli for each sub-block. The total test time is 14 min. The Conners' Kiddie Continuous Performance Test 2nd Edition (K-CPT-2) (2015) was designed for subjects between 4 and 7 years and 11 months of age. The subject sits in front of a computer screen with a white background and is asked to respond by pressing the space bar each time a black drawing other than a ball appears. The stimuli are also divided into blocks, with a total time of 7 min for the entire test. The computerised continuous performance test was shown to have an internal consistency of 0.94 and a correlation coefficient of 0.67 for test-retest reliability, with an administration interval of one to five weeks.23 From this test, we obtained omissions, commissions, hit reaction time (HRT), hit reaction time inter-stimulus interval change (HRT-ISI) and hit reaction time block change (HRT-Block). A T score with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10 was applied for analysis.

To assess the functional impairment of each participant, the Weiss Functional Impairment Scale (WFIRS-P) was used for the parents of the participants. They were administered before the start of telerehabilitation and after completing six months of treatment. The scales were delivered on paper or by email for both parents to fill in together. The WFIRS scale is made up of 50 questions. A mother/father is asked to rate the functional impact on the child in the last month. The items are grouped into six domains (family, learning and school, life skills, self-concept, social activities and risk activities). A 4-point Likert scale is used (from 0, never, to 3, very often), such that any item with a score of 2 or 3 points represents clinical deterioration. The final score of the scale can be calculated using the total score or the score for each particular domain. For clinical purposes, any domain with at least two items scoring 2, one item scoring 3, or a mean score >1.5 can be considered to represent impairment. The WFIRS-P scale has psychometric validation in several studies that support it as a valid measure of functional impairment in clinical studies of children and adolescents with impaired executive functions. This scale demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.93) for each domain and for the scale as a whole and a Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.93 for test-retest reliability. Furthermore, it has moderate convergent validity with other measurement instruments.24,25

To study each participant's family structure, a semi-structured interview was conducted with the parents in which they had to answer the following questions: whether the participant has a relationship with their father and mother; how many hours per day they work; number of siblings; number of people living together; who assisted the subject during the telerehabilitation; whether they had any technical problems and whether it was resolved; whether or not they consider the telerehabilitation useful for their child and if so, in what way; what they think the benefits are; whether they would recommend it; and whether they are satisfied (score, from 1, not at all satisfied, to 10, very satisfied).

TelerehabilitationThe program used for telerehabilitation was designed by the Spanish group Rehametrics in 2011 and can be run on both an Android tablet and a personal computer. This program with 220 exercises for physical and cognitive rehabilitation uses virtual reality, the Kinect sensor and touch technology depending on the selected activity, and allows it to be carried out at the user's home.

All exercises included in Rehametrics have multiple customisation options that allow the therapist to adjust the level and degree of difficulty of each exercise to the capabilities and clinical goals of each subject. During each session, the program monitors the exercises performed and checks the degree and quality of execution. It also collects information from the sessions completed by the participants to generate automatic reports that allow the therapist to objectively monitor the subject's progress.26

In this study, motor rehabilitation activities were not chosen, since not all participants had a Kinect at home to carry them out. Finally, 15 cognitive exercises were selected based on the age and needs of the participants to rehabilitate language (comprehension, expression), executive functions (categorisation, visual and verbal working memory), processing speed, attention (divided, selective and sustained) and visual-spatial skills (orientation, perceptual integration, visual perception, simultanagnosia). The "cupboard" and "kitchen" activities exercise categorisation and visual working memory ecologically, as the participant has to put the items away based on previous instructions that they have to remember. For the analysis, the level and difficulty of each subject in each activity at the beginning of treatment and at the end of the study were taken; the analysis variable was corrected based on the number of sessions completed by the participant. The level and difficulty were scored numerically and in increasing order, with the initial and easiest value being number 1. The number of weeks and sessions, and the time in hours of treatment, were also recorded for analysis.

ProcedureThe participants selected by the study coordinator according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria were treated by the same treating neuropsychologist.

Before starting telerehabilitation, participants completed the neuropsychological assessment and completed the Weiss functional impairment rating scale with an independent neuropsychologist different from the one who carried out the treatment. After completing six months of therapy, the same neuropsychologist contacted the parents to do the Weiss functional impairment rating scale again (one per family) and a questionnaire to find out if they had any technical problems, if they were resolved, if they considered telerehabilitation useful for their child and if so, in what way it was useful, if they would recommend it and what they considered to be the benefits and drawbacks of this type of therapy.

The parents were then contacted by video call by the treating neuropsychologist, different from the one who did the neuropsychological assessments, to assist them in installing the program, give them the password and guide them on how to help their children do the exercises. The internet connection and the correct functioning of the telerehabilitation program were also certified during this call.

After confirming that the Rehametrics program and the internet were working correctly, and that the parents were able to help their children with the activity, the neuropsychologist selected and scheduled the weekly cognitive rehabilitation exercises based on each subject's the needs, so that each session had a duration of 30 min and the participant could connect at least twice a week. The Rehametrics telerehabilitation program recorded data on the responses of each participant for each activity, as well as the time and frequency of each connection. The data was sent weekly online to the treating neuropsychologist, who personalised each of the exercises for the following week in level and degree of difficulty.

Throughout the study, the treating neuropsychologist communicated weekly by email and monthly by telephone with the families to reinforce adherence to the treatment and assist the parents with any questions or queries they had.

AnalysisContinuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation if the distribution was normal, or as median [interquartile range] if it was asymmetric. Categorical variables are expressed as percentages or proportions. Normality of continuous variables was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test and graphically with a histogram. Homoscedasticity was evaluated using Levene's test.

To compare normal continuous variables, the Student's t test was used for paired variables, and, if the assumptions of normality were not met, the Wilcoxon test was used. For categorical variables, the χ2 test or the Fisher test was used if the expected value in any cells was <5.

The categorical variables analysed were: gender; presence of father and mother; cohabitants; who helps the participant in rehabilitation; whether there were technical problems and whether or not they were resolved. The continuous variables included in the analysis were: the domains of the Weiss Functional Impairment Rating Scale (family, self-concept, school, social activities, risk activities), indices of the WISC-V intelligence scale for children (verbal comprehension, fluid reasoning, working memory, processing speed and full scale intelligence quotient), variables of the CPT-3 and K-CPT-2 continuous performance test (omissions, commissions, hit reaction time [HRT], HRT block change and HRT Inter-Stimulus Interval [ISI] change), level and degree of difficulty of the selected activities of the telerehabilitation program (number of weeks, number of sessions, total work time, sustained, selective and divided attention, verbal and visual working memory, categorisation, processing speed, spatial orientation, visual perceptive integration, visual perception, simultanagnosia, cupboard, kitchen, language comprehension and expression).

To determine whether there was any relationship between the telerehabilitation activities performed and the number of sessions, we carried out a linear regression between these variables once the assumptions of the model were confirmed (linearity, homoscedasticity, normality, non-collinearity). The ANOVA test was applied to analyse the relationship between family structure and the number of sessions carried out. The post-hoc Bonferroni test was then used to study significant differences between the model variables in ANOVA.

Statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05; the effect size was evaluated using Cohen's d or Kramer's V or ε2, as appropriate.

The data collected by both neuropsychologists was uploaded into a database, assigning each participant a random letter, so that they would be anonymous at the time of analysis by the study coordinator. The analysis was carried out using the Stata 13.0 statistical package.

The study performed complies with the ethical standards proposed in the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, amended in 2013. It was also approved by the Ethics Committee of our institution, and we asked the parents to sign the informed consent form and asked for assent from the children.

ResultsOf the 64 subjects who underwent telerehabilitation during the study period, 25 were selected for having participated for more than six months in the telerehabilitation program of our hospital's Paediatric Neurology Department during the COVID-19 pandemic from March 2020 to May 2021. However, three of them were ruled out for not having accessed the platform twice a week. Finally, the study was carried out with 22 participants, 12 female (mean age, 9.64 ± 3.76 years) and 10 male (9.24 ± 3.29 years; p = 0.79). With regard to family structure, 95% reported maintaining a relationship with their father, 100%, with their mother, and in 60% of the cases, they lived with both; in 90% of the cases, it was the mother who helped them do the telerehabilitation activities. On average, parents worked a 9.13-h day (95% confidence interval [95%CI], 8.63–9.63). In 36% of cases, the participants were only children, 45% had one sibling and 19%, two or more. Regarding the technical aspect, 13% reported having had some problem, but in all cases, problems were resolved without interfering with the normal course of the rehabilitation. Although 31% of participants stated that telerehabilitation did not replace face-to-face treatment, 86% positively rated that it was possible without having to travel. Lastly, the participants were very satisfied with the program and gave it an average score of 9 (95%CI, 8.63–9.36) and in 100% of cases, would recommend it.

At a therapeutic level, although 56% of the participants only did telerehabilitation, some were able to continue with other rehabilitation therapies. In many cases, during much of the social isolation, they were carried out in a virtual format; 19% of the participants did psychology, 5% psychoeducation, 10% both, 5% speech and language therapy and 5% occupational therapy.

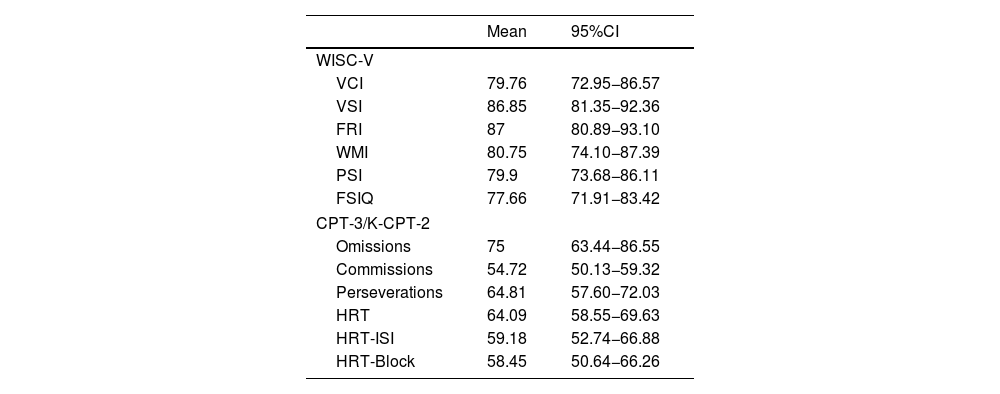

Table 1 shows the results of the neuropsychological assessment and the attention-related profile measured with the continuous attention test carried out on the participants before starting the telerehabilitation.

Results of the participants' neuropsychological assessments at the beginning of the therapy.

| Mean | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|

| WISC-V | ||

| VCI | 79.76 | 72.95−86.57 |

| VSI | 86.85 | 81.35−92.36 |

| FRI | 87 | 80.89−93.10 |

| WMI | 80.75 | 74.10−87.39 |

| PSI | 79.9 | 73.68−86.11 |

| FSIQ | 77.66 | 71.91−83.42 |

| CPT-3/K-CPT-2 | ||

| Omissions | 75 | 63.44−86.55 |

| Commissions | 54.72 | 50.13−59.32 |

| Perseverations | 64.81 | 57.60−72.03 |

| HRT | 64.09 | 58.55−69.63 |

| HRT-ISI | 59.18 | 52.74−66.88 |

| HRT-Block | 58.45 | 50.64−66.26 |

FRI: fluid reasoning index; FSIQ: full-scale intelligence quotient; HRT: hit reaction time; HRT-Block: hit reaction time block change; HRT-ISI: hit reaction time inter-stimulus interval change; PSI: processing speed index; VCI: verbal comprehension index; VSI: visual spatial index; WMI: working memory index. 95%CI: 95% confidence interval.

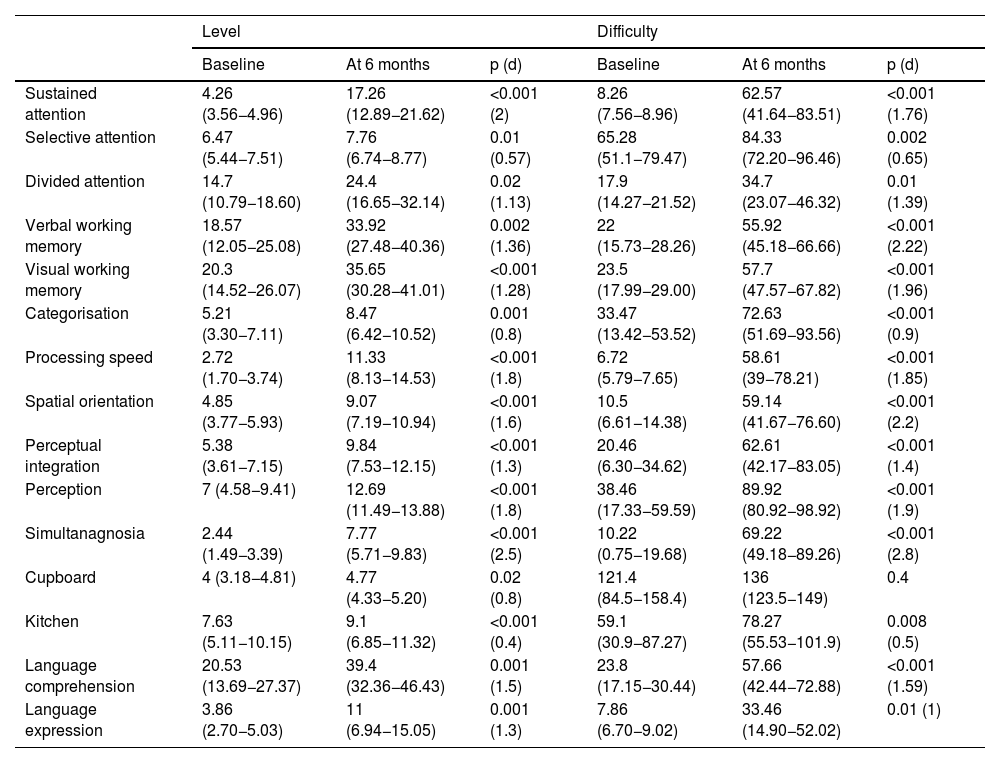

The participants completed telerehabilitation for an average of 2,736.22 h (95%CI, 875.82–4,596.63), distributed over an average of 112.18 sessions (95%CI, 57.73–166.63), over an average of 36.63 weeks (95%CI, 28.17–45.09). When comparing the level and degree of difficulty of the exercises selected for the participants at the beginning and after six months of therapy, significant improvement was found with a large effect size in all areas: attention (sustained, selective and divided); executive functions (verbal and visual working memory, categorisation, processing speed, cupboard, kitchen); visual-spatial skills (spatial orientation, perceptual integration, perception, simultanagnosia); and language (comprehension and expression) (Table 2).

Level and degree of difficulty per telerehabilitation exercise at the start and after six months of therapy.

| Level | Difficulty | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | At 6 months | p (d) | Baseline | At 6 months | p (d) | |

| Sustained attention | 4.26 (3.56−4.96) | 17.26 (12.89−21.62) | <0.001 (2) | 8.26 (7.56−8.96) | 62.57 (41.64−83.51) | <0.001 (1.76) |

| Selective attention | 6.47 (5.44−7.51) | 7.76 (6.74−8.77) | 0.01 (0.57) | 65.28 (51.1−79.47) | 84.33 (72.20−96.46) | 0.002 (0.65) |

| Divided attention | 14.7 (10.79−18.60) | 24.4 (16.65−32.14) | 0.02 (1.13) | 17.9 (14.27−21.52) | 34.7 (23.07−46.32) | 0.01 (1.39) |

| Verbal working memory | 18.57 (12.05−25.08) | 33.92 (27.48−40.36) | 0.002 (1.36) | 22 (15.73−28.26) | 55.92 (45.18−66.66) | <0.001 (2.22) |

| Visual working memory | 20.3 (14.52−26.07) | 35.65 (30.28−41.01) | <0.001 (1.28) | 23.5 (17.99−29.00) | 57.7 (47.57−67.82) | <0.001 (1.96) |

| Categorisation | 5.21 (3.30−7.11) | 8.47 (6.42−10.52) | 0.001 (0.8) | 33.47 (13.42−53.52) | 72.63 (51.69−93.56) | <0.001 (0.9) |

| Processing speed | 2.72 (1.70−3.74) | 11.33 (8.13−14.53) | <0.001 (1.8) | 6.72 (5.79−7.65) | 58.61 (39−78.21) | <0.001 (1.85) |

| Spatial orientation | 4.85 (3.77−5.93) | 9.07 (7.19−10.94) | <0.001 (1.6) | 10.5 (6.61−14.38) | 59.14 (41.67−76.60) | <0.001 (2.2) |

| Perceptual integration | 5.38 (3.61−7.15) | 9.84 (7.53−12.15) | <0.001 (1.3) | 20.46 (6.30−34.62) | 62.61 (42.17−83.05) | <0.001 (1.4) |

| Perception | 7 (4.58−9.41) | 12.69 (11.49−13.88) | <0.001 (1.8) | 38.46 (17.33−59.59) | 89.92 (80.92−98.92) | <0.001 (1.9) |

| Simultanagnosia | 2.44 (1.49−3.39) | 7.77 (5.71−9.83) | <0.001 (2.5) | 10.22 (0.75−19.68) | 69.22 (49.18−89.26) | <0.001 (2.8) |

| Cupboard | 4 (3.18−4.81) | 4.77 (4.33−5.20) | 0.02 (0.8) | 121.4 (84.5−158.4) | 136 (123.5−149) | 0.4 |

| Kitchen | 7.63 (5.11−10.15) | 9.1 (6.85−11.32) | <0.001 (0.4) | 59.1 (30.9−87.27) | 78.27 (55.53−101.9) | 0.008 (0.5) |

| Language comprehension | 20.53 (13.69−27.37) | 39.4 (32.36−46.43) | 0.001 (1.5) | 23.8 (17.15−30.44) | 57.66 (42.44−72.88) | <0.001 (1.59) |

| Language expression | 3.86 (2.70−5.03) | 11 (6.94−15.05) | 0.001 (1.3) | 7.86 (6.70−9.02) | 33.46 (14.90−52.02) | 0.01 (1) |

d: Cohen's d for effect size.

The values express mean (95% confidence interval).

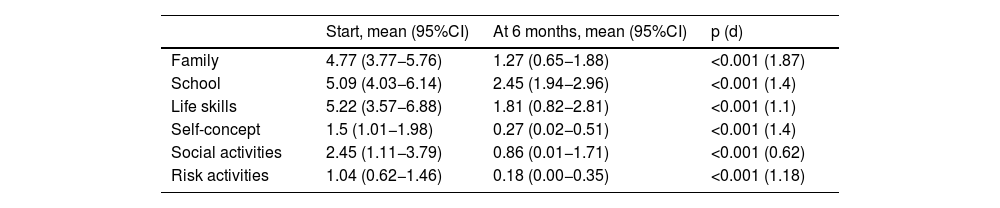

When analysing the Weiss Functional Impairment Scale (WFIRS-P) completed by the families before starting telerehabilitation, impairment was determined with a mean score >1.5 in five of the six domains assessed: family, learning and school, life skills, self-concept, social activities and risk. After six months of telerehabilitation, significant improvements with large effect sizes were observed in all domains of the WFIRS-P scale; even in the domains that evaluated family aspects, self-concept, social activities and risk activities, a mean was achieved within normal values (Table 3).

Weiss Functional Impairment Scale at the start and after six months of telerehabilitation.

| Start, mean (95%CI) | At 6 months, mean (95%CI) | p (d) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family | 4.77 (3.77−5.76) | 1.27 (0.65−1.88) | <0.001 (1.87) |

| School | 5.09 (4.03−6.14) | 2.45 (1.94−2.96) | <0.001 (1.4) |

| Life skills | 5.22 (3.57−6.88) | 1.81 (0.82−2.81) | <0.001 (1.1) |

| Self-concept | 1.5 (1.01−1.98) | 0.27 (0.02−0.51) | <0.001 (1.4) |

| Social activities | 2.45 (1.11−3.79) | 0.86 (0.01−1.71) | <0.001 (0.62) |

| Risk activities | 1.04 (0.62−1.46) | 0.18 (0.00−0.35) | <0.001 (1.18) |

d: Cohen's d for effect size.

The values express mean (95% confidence interval).

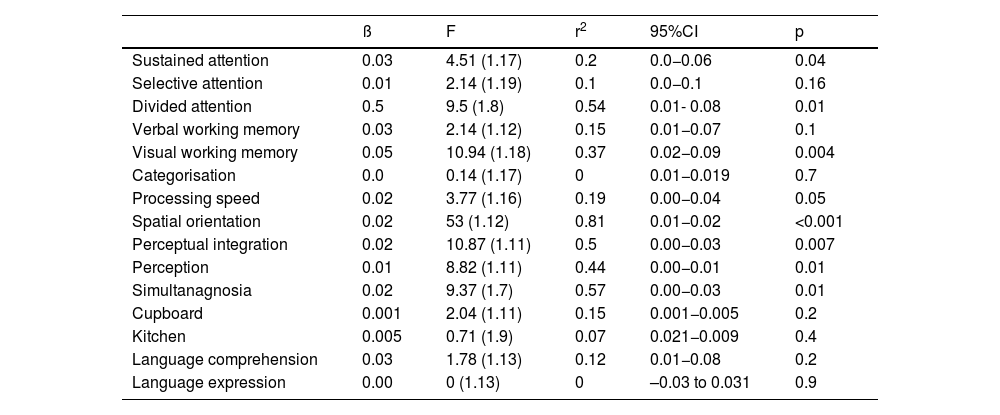

To analyse whether there was any relationship between the number of telerehabilitation sessions carried out by each participant and the level achieved in the different exercises after six months of therapy, we carried out a linear regression in which we found a positive correlation in the activities that rehabilitate executive functions (visual working memory, processing speed), attention-related functions (sustained attention, divided attention) and visual-spatial skills (spatial orientation, perceptual integration, perception, simultanagnosia). The model accounts for 19% of the total variance in processing speed (r2 = 0.19), 20% in sustained attention (r2 = 0.2), 37% in visual working memory (r2 = 0.37), 44% in perception (r2 = 0.44) and more than 50% in divided attention (r2 = 0.54), spatial orientation (r2 = 0.81), perceptual integration (r2 = 0.5) and simultanagnosia (r2 = 0.57) (Table 4).

Number of telerehabilitation sessions necessary to go up one level after each exercise.

| ß | F | r2 | 95%CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustained attention | 0.03 | 4.51 (1.17) | 0.2 | 0.0−0.06 | 0.04 |

| Selective attention | 0.01 | 2.14 (1.19) | 0.1 | 0.0−0.1 | 0.16 |

| Divided attention | 0.5 | 9.5 (1.8) | 0.54 | 0.01- 0.08 | 0.01 |

| Verbal working memory | 0.03 | 2.14 (1.12) | 0.15 | 0.01−0.07 | 0.1 |

| Visual working memory | 0.05 | 10.94 (1.18) | 0.37 | 0.02−0.09 | 0.004 |

| Categorisation | 0.0 | 0.14 (1.17) | 0 | 0.01−0.019 | 0.7 |

| Processing speed | 0.02 | 3.77 (1.16) | 0.19 | 0.00−0.04 | 0.05 |

| Spatial orientation | 0.02 | 53 (1.12) | 0.81 | 0.01−0.02 | <0.001 |

| Perceptual integration | 0.02 | 10.87 (1.11) | 0.5 | 0.00−0.03 | 0.007 |

| Perception | 0.01 | 8.82 (1.11) | 0.44 | 0.00−0.01 | 0.01 |

| Simultanagnosia | 0.02 | 9.37 (1.7) | 0.57 | 0.00−0.03 | 0.01 |

| Cupboard | 0.001 | 2.04 (1.11) | 0.15 | 0.001−0.005 | 0.2 |

| Kitchen | 0.005 | 0.71 (1.9) | 0.07 | 0.021−0.009 | 0.4 |

| Language comprehension | 0.03 | 1.78 (1.13) | 0.12 | 0.01−0.08 | 0.2 |

| Language expression | 0.00 | 0 (1.13) | 0 | –0.03 to 0.031 | 0.9 |

Taking into account the positive correlation between the number of telerehabilitation sessions carried out by the participant and the progress observed in some areas studied, we analysed whether or not the family structure might have influenced the total number of sessions carried out. The results of the ANOVA test indicated that there were no statistically significant differences between the participants who lived with one of their parents and those who lived with both (F(1.20) = 2.01; p = 0.17). The ANOVA also showed no significant differences between participants who had no siblings, those who had one, and those who had two or more (F(2.19) = 1.13; p = 0.34).

DiscussionDue to the confinement related to the COVID-19 pandemic, many children with neurodevelopmental disorders could not continue with their therapies as they had been doing, and had to find different ways and tools that would allow them to continue with their rehabilitation. Telemedicine in general and telerehabilitation in particular grew as an opportunity to attend to the therapeutic needs of these children. We have made a study here of this mode of asynchronous, distance cognitive rehabilitation in a group of children with neurodevelopmental disorders.

In line with previous studies analysing the benefits of telerehabilitation in subjects with cognitive impairment caused by different conditions, such as epilepsy or stroke, we found that in children with neurodevelopmental disorders who did telerehabilitation for a period of over six months, cognitive improvements were also observed in language (comprehension, expression), executive functions (categorisation, visual and verbal working memory), processing speed, attention (divided, selective and sustained) and visual-spatial skills (orientation, perceptual integration, visual perception and simultanagnosia).19,27 Also like other authors, we found that a greater number of sessions was positively correlated with a greater degree of cognitive progress, especially in visual-spatial skills, attention-related functioning, visual working memory and processing speed.28,29 Furthermore, in our model, the number of sessions explained a large part of the observed changes, especially in visual-spatial skills, divided attention and visual working memory. It is likely that a larger sample size or more study time would have also allowed us to observe this positive correlation in the other cognitive functions worked on.

With regard to the WFIRS-P completed by the participants' families, a significant improvement was found in all the domains assessed and in three of them (family, social activities and self-concept) the degree of improvement even moved them out of the category of impairment, achieving values within normal ranges. This situation, also reported in other studies, shows that the breakthroughs achieved in telerehabilitation can be positively converted into an improvement in the functionality of individuals in the environments where they live their lives.29,30

When using this type of technology, technical problems are often a barrier to be overcome. Problems ranging from how to install the platform, having a computer or tablet with the appropriate characteristics, or having internet broadband that allows the correct flow of data, to using the program and being in a position to adequately help the children were situations that could have hindered the application of the telerehabilitation. Studies have shown that direct, clear and frequent communication with the family is a fundamental component for making them feel safe in managing the programme and achieving greater adherence and the feeling of being cared for.31 For this reason, we believe that in our study, the help provided from the beginning and throughout the therapy by the treating neuropsychologist was essential to overcome these challenges and achieve the active participation of the family. Although in our study, 13% of participants had some type of technical problem, slightly lower than the 20% reported in other publications, it did not interfere with the normal course of their rehabilitation.32 Also, in line with other studies, our patients reported a high level of satisfaction, which usually increases adherence and acceptance of these new rehabilitation tools. It is worth noting, however, that just over a third of the subjects stated that telerehabilitation does not replace in-person therapy.19

One limitation to consider in this study is the six months of telerehabilitation the participants had to have completed. Some cognitive aspects often require more treatment time for changes to become evident. Additionally, the need for at least nine months between two neuropsychological assessments meant we were unable to perform this objective comparison. However, we believe our study shows that this group of children with neurodevelopmental disorders who did telerehabilitation not only achieved cognitive improvements but also decreased their functional impairment in different areas of development, with a high degree of satisfaction.

ConclusionsThe COVID-19 pandemic was a unique opportunity to exponentially develop telemedicine in general and telerehabilitation in particular. While conventional face-to-face treatment is limited by confinement in relation to the pandemic, telerehabilitation is offered as an alternative tool which, although it does not replace face-to-face treatment, can achieve significant cognitive and functional improvements in children with neurodevelopmental disorders.

FundingThe authors did not receive any financial support or funding for the completion of this article.

Author contributionsVaucheret Paz, Guillermo Agosta and Mariana Giacchino participated in the conception and design of the study. Mariana Giacchino monitored and treated the subjects in telerehabilitation. Leist, Petracca and Chirila participated in data collection. Vaucheret Paz and Agosta carried out the statistical analysis for the study. Vaucheret Paz, Agosta, Petracca, Leist and Chirilla performed the interpretation of the results. The article was written by Esteban Vaucheret and Giacchino, while the critical review of the content was carried out by all the authors, who approve the final version of the manuscript and are responsible for all aspects of it, ensuring that any issues related with the veracity or integrity of all parts of the manuscript were adequately investigated and resolved.

Conflicts of interestThe authors of this paper have no conflicts of interest.