Patients with bipolar disorder type I (BP-I) often present with impairments in cognitive function. Offspring unaffected by the disorder can also present with cognitive dysfunction. The objective of this study was to compare the cognitive function of BP-I patients, their unaffected offspring (UO) and healthy control subjects (HC).

MethodsVerbal memory, working memory index, processing speed, attention, verbal and phonological fluency and executive function were evaluated through the application of a neuropsychological battery to three groups made up of BP-I patients that attended the Bipolar Disorder Outpatient Clinic of Clínica San Juan de Dios de Manizales [San Juan de Dios de Manizales Clinic] (n=30), UO (n=32) and control group (n=31). The UO group and the control group were matched by gender, age and level of education.

ResultsMajor differences between the three groups were found in the measures of cognitive functions (except in semantic fluency). The HC group showed better cognitive performance in all the functions. Post-hoc analysis showed similar results in the cognitive performance between BP-I and UO except in verbal learning and executive function tasks where the results were better in UO. A better performance in the control group was found, compared to the UO group, in executive function, attention, working memory, and semantic fluency and phonological areas.

ConclusionsThese results indicate that the offspring of patients with BP-I present with cognitive impairments without suffering from the disorder. This suggests that cognitive dysfunction presents without diagnosis and supports the hypothesis that it can correspond to a BP-I endophenotype.

Los pacientes con trastorno bipolar tipo I (TB-I) presentan con frecuencia alteraciones en las funciones cognitivas. Los hijos no afectados por el trastorno pueden presentar déficits cognitivos. El objetivo del presente estudio es comparar las funciones cognitivas en pacientes con TB-I, sus hijos no afectados (UO) y controles sanos (HC).

MétodosSe evaluó la memoria verbal, el índice de la memoria de trabajo, velocidad de procesamiento, atención, fluidez verbal y fonológica y función ejecutiva mediante la aplicación de una batería neuropsicológica a 3 grupos conformados por pacientes con TB-I asistentes a la Clínica Ambulatoria de Trastorno Bipolar de la Clínica San Juan de Dios de Manizales (n=30), UO (n=32) y HC (n=31). Los grupos de UO y HC se emparejaron por sexo, edad y escolaridad.

ResultadosSe encontraron diferencias significativas entre los 3 grupos en las medidas de sus funciones cognitivas, excepto en la fluidez semántica. El grupo de HC mostró mejor rendimiento cognitivo en todas las funciones. El análisis post hoc mostró resultados similares en el funcionamiento cognitivo entre TB-I y UO excepto en las pruebas de aprendizaje verbal y función ejecutiva, donde los resultados fueron mejores en los UO. Al comparar los grupos de HC y UO, se encontró un mejor rendimiento del primero en función ejecutiva, atención, índice de memoria de trabajo y fluidez semántica y fonológica.

ConclusionesEstos resultados indican que los hijos de pacientes con TB-I presentan alteraciones cognitivas sin padecer el trastorno. Esto indica que las alteraciones cognitivas se manifiestan sin que haya diagnóstico y robustece la hipótesis de que puedan corresponder a un endofenotipo del TB-I.

Bipolar I disorder (BP-I) is a psychopathological condition with impairments in executive functioning, attention, processing speed, and verbal memory.1 Cognitive dysfunction has a negative impact on socio-occupational outcome, quality of life and inferior functioning.2-4 Offspring of parents with bipolar disorder are at an increased risk of developing psychiatric disorders or cognitive impairments.5,6 These impairments can be conceptualized as an endophenotype.

As proposed by Gottesman and Gould, an endophenotype can be defined as a characteristic that is not easily detected. This characteristic is associated with illness, heritable, state independent, it co-segregates within families with illness and presents itself at a higher rate in unaffected family members when compared to the general population implying greater susceptibility to develop disease.7,8 BP-I candidate endophenotypes include neuroanatomical changes, abnormal physiological and biochemical measures, and cognitive impairments like attention, verbal learning, and memory deficits.9 The candidates neurocognitive endophenotypes appear to be heritable.10,11

Even though cognitive impairment in unaffected first-degree relatives is a frequent feature and seems to be a diagnostic endophenotype, more evidence is needed to confirm this notion.12 The studies in unaffected relatives of patients in comparison to the general population show inconsistent findings.6,13 The deficits in verbal fluency, verbal learning/memory, attention, and processing speed are most prominent in the unaffected relatives. In contrast, intellectual capabilities, immediate memory, working memory, and visual-spatial learning/memory seem to be preserved.6,14,15 Cognitive assessment is an opportunity to delimitate cognitive endophenotypes, it might predict the development of a severe mental illness and may be the targets of early cognitive remediation programs.16,17 The present study aims to assess and to compare cognitive performance in a group of patients diagnosed with BP-I, their unaffected offspring (UO), and a healthy group with no family history of mental disorders, on parameters of verbal learning, working memory index, processing speed, attention, verbal and phonological fluency and executive function.

MethodsSampleThe sample was obtained from the BP-I follow-up program at San Juan de Dios Clinic in Manizales (Colombia). The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Caldas and by San Juan de Dios Clinic. After complete description of the study, a written informed consent for participation was received from all subjects. The first group included adult patients with BP-I diagnosis (BP-I group). All participants were evaluated with the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (DIGS), which has been confirmed as a valid and reliable diagnostic measure in the Latin American population.18 A review of the medical record was also made. The second group was the unaffected adult offspring (UO) of the first group, screened negative for mental disorders with DIGS. The third group was the healthy control (HC). The HC group was selected from visitors of inpatients, they were matched to the UO group on sex, age, and educational level, and they were free of psychiatric illness assessed with the DIGS, they did not have any family history or medical record of mental disorders. In the 3 groups, subjects with severe or unstable conditions such as medical or neurological problems, substance use disorders, and illiterate condition were excluded.

Neuropsychological assessmentBefore the assessment, the first group was in a euthymic phase of the illness defined by at least 6 months of remission, without changes in the pharmacological treatment, a Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD)19 score <6, and a Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS)20 score <6.

The neuropsychological assessment was carried out by a neuropsychologist who was blind to the diagnoses. The following tests were used in the evaluation: Short-term auditory-verbal memory was assessed using the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) in which subjects had to learn a series of words presented orally over 5 trials and to immediately recall them after each presentation. They were also asked to recall with a 20-min delay (delayed recall) after being shown a series of distractors.21 Working memory index was assessed with Arithmetic of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-III), in which subjects had to do mental arithmetic to solve simple problems, Digit Span of WAIS-III in which subjects had to recall serially sequences of digits, and letter-number sequencing of WAIS-III in which subjects had to read a sequence of numbers and letters and recall the numbers in ascending order and the letters in alphabetical order.22 Processing speed was assessed with the digit symbol-coding subtest of the WAIS-III in which subjects had to pair numbers from 1 to 9 with a symbol as much as they can, and Trail Making Test parts A and B in which subjects had to connect numbers and letters in order in as little time as possible.23 Attention was assessed with the Symbol Search Subtest of the WAIS-III in which a subject had to determine if a target symbol appeared in a set of distractor symbols, and Stroop Color-Word Interference Test (STROOP).24 Verbal and phonological fluency were assessed with Neuropsi subtests in which subjects had to produce a maximum number of words during a 1-min interval from the same semantic category (i.e., “animals”) and afterwards from a phonological cue (i.e., “p”).25 Executive function was assessed with the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) in which participants had to classify series of cards into 3 categories, after having found the experimenter's classification rule (color, number, or forms).26

The test scores of the subtests were made following the instructions of the developers. Raw scores for TMT A, TMT B and WCST errors. The test scores of RAVLT, STROOP, digit symbol-coding, arithmetic, digit span, letter-number sequencing and working memory index were standardized by age. The WCST, verbal and phonological fluency were standardized by age and education level.

Statistical analysisTo address statistically significant group differences for age and education levels between the 3 groups, age and education level normative data was used to compute subtests of the neuropsychological assessment. The data was analyzed using SPSS 23.0 for Windows.27 Prior to statistical testing, the data was examined for normality with the Shapiro-Wilk test. The quantitative variables and scores on the neuropsychological test were reported in mean±standard deviation values. The categorical variables were reported in frequencies and percentages.

Comparison between the groups were performed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables when they had normal distribution, and χ2 tests were used for categorical variables. When normal distribution was not met, Kruskal-Wallis tests were applied. Post-hoc group comparisons were performed with Tukey test and Bonferroni test as appropriate. The effect sizes were calculated for each of the 2 group comparisons with the Cohen d test to parametric variables and Mann-Whitney test to non-parametric variables.

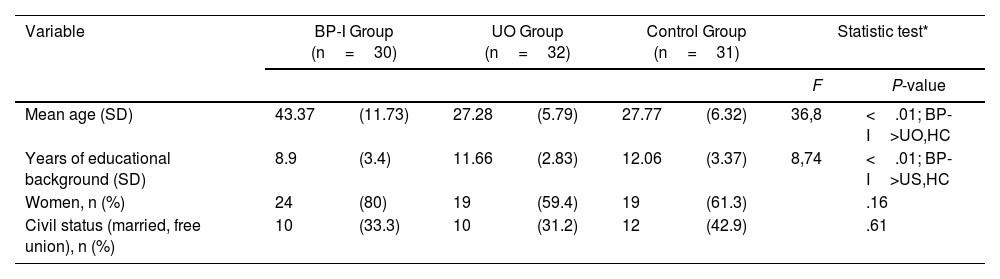

ResultsDemographic data for the BP-I group, the UO group and HC group are displayed in Table 1. As expected, the BP-I group was older and with less educational degree than their UO. The UO group and control subjects were matched by age, educational degree, gender, and civil status.

Sociodemographic description of the sample.

| Variable | BP-I Group (n=30) | UO Group (n=32) | Control Group (n=31) | Statistic test* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | P-value | |||||||

| Mean age (SD) | 43.37 | (11.73) | 27.28 | (5.79) | 27.77 | (6.32) | 36,8 | <.01; BP-I>UO,HC |

| Years of educational background (SD) | 8.9 | (3.4) | 11.66 | (2.83) | 12.06 | (3.37) | 8,74 | <.01; BP-I>US,HC |

| Women, n (%) | 24 | (80) | 19 | (59.4) | 19 | (61.3) | .16 | |

| Civil status (married, free union), n (%) | 10 | (33.3) | 10 | (31.2) | 12 | (42.9) | .61 | |

BP-I: bipolar I disorder; HC: healthy control; SD: standard deviation; UO: unaffected offspring of bipolar I patients.

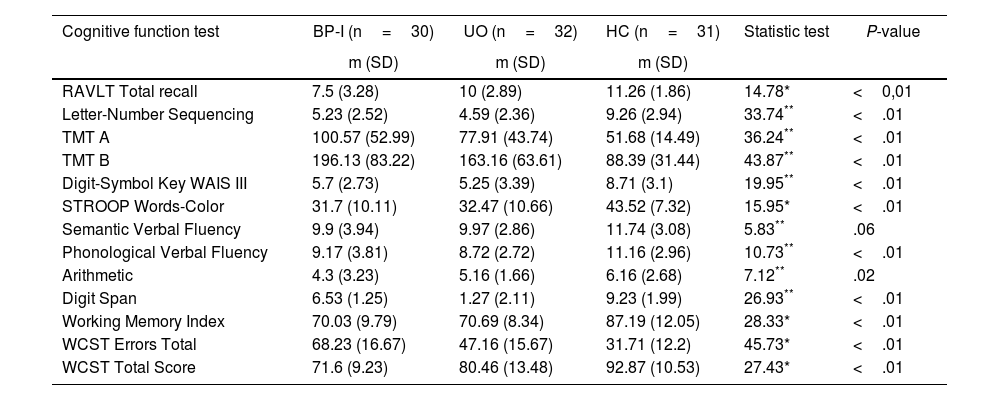

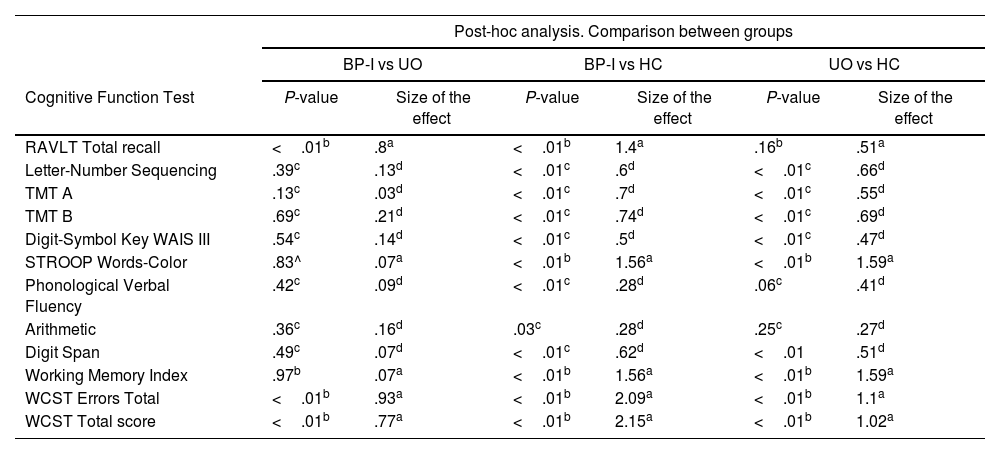

There was a statistical difference between the groups in overall cognitive performance, except the verbal fluency (Table 2). Post-hoc analysis revealed that BP-I group had worse performance in RAVLT (P<.01; SE=.8), WCST errors (P<.01; SE=.93), and WCST total score (P<.01; SE=.77) than the UO group. The BP-I group had lower performance results than the HC on all subtests, except verbal fluency. Comparison of the UO and HC groups indicated that the UO group had lower performance results than the HC on letter-number sequencing, TMT A, TMT B, digit symbol-coding, STROOP, digit span, working memory index and WCST (Table 3).

Comparison of BP-I patients, unaffected offspring and control groups in the neuropsychological tests.

| Cognitive function test | BP-I (n=30) | UO (n=32) | HC (n=31) | Statistic test | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m (SD) | m (SD) | m (SD) | |||

| RAVLT Total recall | 7.5 (3.28) | 10 (2.89) | 11.26 (1.86) | 14.78* | <0,01 |

| Letter-Number Sequencing | 5.23 (2.52) | 4.59 (2.36) | 9.26 (2.94) | 33.74** | <.01 |

| TMT A | 100.57 (52.99) | 77.91 (43.74) | 51.68 (14.49) | 36.24** | <.01 |

| TMT B | 196.13 (83.22) | 163.16 (63.61) | 88.39 (31.44) | 43.87** | <.01 |

| Digit-Symbol Key WAIS III | 5.7 (2.73) | 5.25 (3.39) | 8.71 (3.1) | 19.95** | <.01 |

| STROOP Words-Color | 31.7 (10.11) | 32.47 (10.66) | 43.52 (7.32) | 15.95* | <.01 |

| Semantic Verbal Fluency | 9.9 (3.94) | 9.97 (2.86) | 11.74 (3.08) | 5.83** | .06 |

| Phonological Verbal Fluency | 9.17 (3.81) | 8.72 (2.72) | 11.16 (2.96) | 10.73** | <.01 |

| Arithmetic | 4.3 (3.23) | 5.16 (1.66) | 6.16 (2.68) | 7.12** | .02 |

| Digit Span | 6.53 (1.25) | 1.27 (2.11) | 9.23 (1.99) | 26.93** | <.01 |

| Working Memory Index | 70.03 (9.79) | 70.69 (8.34) | 87.19 (12.05) | 28.33* | <.01 |

| WCST Errors Total | 68.23 (16.67) | 47.16 (15.67) | 31.71 (12.2) | 45.73* | <.01 |

| WCST Total Score | 71.6 (9.23) | 80.46 (13.48) | 92.87 (10.53) | 27.43* | <.01 |

BP-I: bipolar I disorder; HC: healthy control; m: mean value; RAVLT: Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; SD: standard deviation; TMT: Trail Making Test; UO: unaffected offspring of bipolar I patients; WAIS: Wechsler Adult Inteligence Test; WCST: Wisconsin Sorting Card Test.

Kruskal-Wallis (gl, 2).

Values are presented as raw scores for TMT A, TMT B and WCST errors total; the test scores of RAVLT, STROOP, digit symbol-coding, arithmetic, digit span, letter-number sequencing and working memory index are standarized by age. The WCST, verbal and phonological fluency are standardized by age and educational level.

Comparison of BP-I patients, unaffected offspring and healthy control groups in the neuropsychological tests.

| Post-hoc analysis. Comparison between groups | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP-I vs UO | BP-I vs HC | UO vs HC | ||||

| Cognitive Function Test | P-value | Size of the effect | P-value | Size of the effect | P-value | Size of the effect |

| RAVLT Total recall | <.01b | .8a | <.01b | 1.4a | .16b | .51a |

| Letter-Number Sequencing | .39c | .13d | <.01c | .6d | <.01c | .66d |

| TMT A | .13c | .03d | <.01c | .7d | <.01c | .55d |

| TMT B | .69c | .21d | <.01c | .74d | <.01c | .69d |

| Digit-Symbol Key WAIS III | .54c | .14d | <.01c | .5d | <.01c | .47d |

| STROOP Words-Color | .83^ | .07a | <.01b | 1.56a | <.01b | 1.59a |

| Phonological Verbal Fluency | .42c | .09d | <.01c | .28d | .06c | .41d |

| Arithmetic | .36c | .16d | .03c | .28d | .25c | .27d |

| Digit Span | .49c | .07d | <.01c | .62d | <.01 | .51d |

| Working Memory Index | .97b | .07a | <.01b | 1.56a | <.01b | 1.59a |

| WCST Errors Total | <.01b | .93a | <.01b | 2.09a | <.01b | 1.1a |

| WCST Total score | <.01b | .77a | <.01b | 2.15a | <.01b | 1.02a |

BP-I: bipolar I disorder; HC: healthy control; RAVLT: Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; TMT: Trail Making Test; UO: unaffected offspring of bipolar I patients; WAIS: Wechsler Adult Inteligence Test; WCST: Wisconsin Card Sorting Test.

Size of the effect calculated from Cohen-d. Effect sizes>.5 are considered moderate and >.8 are high.

P-value calculated from Tukey multiple comparisons test. Average score difference is significant at 0,05 level.

This study compared the cognitive performance between BP-I, UO and HC groups. The main results were: a) working memory deficits were worse in BP-I and UO groups than the HC group, at the expense of digit span that is related with attention, encoding and auditory processing, and auditory working memory; b) significant deficits in attention, speed processing and executive function were present in both BP-I and UO groups; and the short-term auditory-verbal learning and executive function were strongly compromised in BP-I patients. Surprisingly, no differences were found in verbal fluency results.

Although the sample size is small, it can be concluded that the UO share cognitive impairments with their parents, which increases the evidence in favor of considering the cognitive domain as an endophenotype. The cognitive dysfunction in the UO is consonant with studies where similar samples of healthy relatives of BP-I patients were used.28–32 In this study, the BP-I and UO groups had a similar profile in attention, speed processing and executive function, and both had a major difference with HC, which indicates a possible hereditary mechanism of cognition impairment. It is necessary to elucidate pathophysiological mechanisms and possible genetic origins to prove the existence of cognitive endophenotypes. With regard to verbal fluency results, and in agreeance with our findings, some evidence suggests that there is an increased magnitude of impairment in verbal fluency in acute mood states, but this impairment is less prominent in euthymic phase.33 It is possible that some neurocognitive measures like verbal fluency are dependent of mood states factors, but others will be independent from mood states.

Although cognitive impairment has been related with advanced BP-I, with a higher rate of episodes and poor cognitive functioning, this feature is not mandatory, because it is likely that some descendants present the impairment in cognition but not the emotional disorder.28,34 Indeed, the cognitive impairment in first degree relatives of BP-I patients may be present before the development of bipolar disorder and could be a risk factor for the illness;35 however, the mean age of the UO group is above the mean age of onset of bipolar disorder, hence, it is less likely that they develop the disorder. For this reason, it is necessary to develop prospective, longitudinal studies to assess the evolution of cognitive performance in relatives of BP-I patients with the purpose of establishing if cognitive impairment may be considered a risk factor for BP-I.

The study follows the Research Dominium Criteria (RDoC) initiative,36 which suggest the measure of constructs like memory, working memory and attention within the cognitive systems domain to improve the comprehension of mental health-illness processes.37,38 The differences between BP-I and UO groups indicate that cognitive constructs may have different courses and may be related with other symptoms or underlying psychopathological mechanisms. It is probable that short-term auditory-verbal memory and executive function could be affected by biological or environmental mechanisms present in BP-I but no in UO, and working memory, processing speed, attention, and verbal and phonological fluency share underlying mechanisms in both groups. Moreover, the presence of impairments in cognition in other severe mental illnesses and in the unaffected relatives indicates that they can express an independent course.13,17,38–41 Therefore, it is important to develop studies that assess the constructs ranging from genes to circuits to behavioral measures.

There is some evidence that suggest that cognitive dysfunctions have a benign role in the growing and development of offspring of BP-I patients between the ages of 7 and 22 years. Nonetheless, they might have different developmental trajectories and may be negatively impacted by other factors like abuse and mistreatment in childhood/adolescence.42–44 It would be important to conduct longitudinal studies to clarify if the UO with cognitive deficit develop BP-I at a late age or have a more benign life course. Also, it is important to improve the early detection of subumbral symptoms and to establish follow-up programs for the subjects at risk of developing mental illness. It is necessary to analyze the cognitive and executive disfunctions to elucidate if they are predisposing factors for the onset of BP-I.

ConclusionsCognitive impairment in BP-I and their UO, support the notion of neurocognition as an endophenotype for bipolar disorder and suggest that constructs like short-term auditory-verbal memory, working memory, processing speed, attention, verbal and phonological fluency, and executive function of cognitive systems domain may have a different course influenced by hereditary, physiological, and environmental factors. The findings of this study suggest the presence of a heritable and familiar trait in the descendants of BP-I patients, which could contribute to a quantitative increase of these cognitive anomalies. Moreover, the detection of cognitive impairment in UO is necessary to assess its effect in global functioning, to implement early therapeutic approaches and to follow-up on a possible transition towards a mental illness.

LimitationsOne of the limitations of this study was that BD-I and UO groups were not matched by age and the number of years studied. As expected, BD-I patients were older and less educated than the UO group. The age and years studied influence cognitive functioning; however this limitation was minimized by standardizing the test results by age and education as suggested by the literature, except for TMT A, TMT B and WCST errors. Furthermore, we were unable to explore psychosocial factors (e.g., early life trauma, socioeconomic conditions, substance use, perceived stress) and other mental disorders (e.g., attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, learning disorders) as potential determinants of cognitive profiles.

The cross-sectional design is another limitation of this study, where only associations can be shown, excluding any possibility for identifying relationships of causality. The size of the sample is small, which could imply a type II error for multiple comparisons. There was discrepancy by sex considering that women represented 66% of our sample, which could be a bias, due that cognition impairment could be different between males and females with BP-I.

FundingThis study was supported by University of Caldas grant: 0595515.

Conflict of interestsAll authors declare no conflict of interests that could influence their work.

The authors would like to thank San Juan de Dios Clinic and the University of Caldas for the help to carry out the project.