Misophonia, known as hypersensitivity to certain sounds, has a significant impact on psychological well-being. Studies in the literature focus on triggers, responses to triggers, neural mechanisms, and quality of life. Risk factors should be understood to guide the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of misophonia. This systematic review aims to explore the available evidence identifying factors associated with misophonia in the general or clinical population.

Material and methodsThis study was a systematic review protocol. PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Taylor & Francis, and Science Direct electronic databases were searched using the keywords. In the study with no year restriction, factors associated with misophonia were the primary outcomes. Joanna Briggs Institute critical analysis tools were used to assess the methodological quality of the studies.

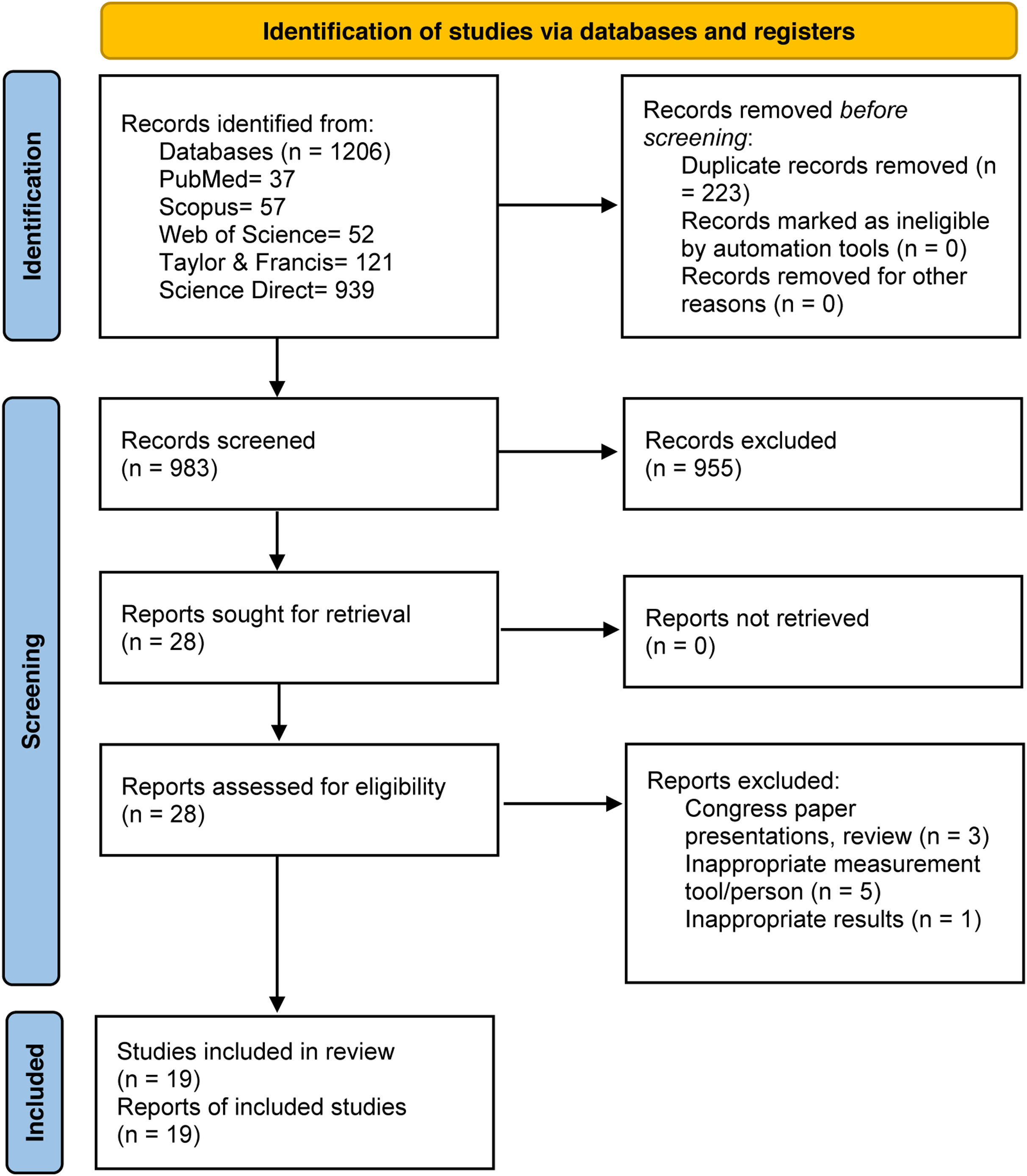

ResultsIn electronic databases, 1206 records were identified, of which 19 were included. In studies the Misophonia Questionnaire (MQ) was frequently used to assess symptoms of misophonia. Methodological quality assessments of the studies ranged from 62.5% to 100%.

ConclusionsMost of the factors associated with misophonia were mental disorders and sociodemographic factors. The presence of mental disorders and female gender were frequently associated with misophonia.

La misofonía, conocida como hipersensibilidad a ciertos sonidos, tiene un impacto significativo en el bienestar psicológico. Los estudios en la literatura se centran en los factores desencadenantes, las respuestas a los factores desencadenantes, los mecanismos neurales y la calidad de vida. Se deben comprender los factores de riesgo para orientar la prevención, el diagnóstico y el tratamiento de la misofonía. Esta revisión sistemática tiene como objetivo explorar las pruebas disponibles que identifican los factores asociados a la misofonía en la población general o clínica.

Material y métodosEste estudio fue un protocolo de revisión sistemática. Se realizaron búsquedas en las bases de datos electrónicas PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Taylor & Francis y Science Direct utilizando las palabras clave. En el estudio sin restricción de año, los factores asociados con la misofonía fueron los resultados primarios. Se utilizaron herramientas de análisis crítico del Instituto Joanna Briggs para evaluar la calidad metodológica de los estudios.

ResultadosEn las bases de datos electrónicas se identificaron 1206 registros, de los cuales se incluyeron 19. En los estudios se utilizó con frecuencia el Misophonia Questionnaire para evaluar los síntomas de misofonía. Las evaluaciones de la calidad metodológica de los estudios oscilaron entre el 62,5% y el 100%.

ConclusionesLa mayoría de los factores asociados a la misofonía fueron trastornos mentales y factores sociodemográficos. La presencia de trastornos mentales y el sexo femenino se asociaron frecuentemente con la misofonía.

Misophonia, which was first introduced to the literature by Jastreboff and Jastreboff in 2001, is a psychiatric disorder characterized by displeasure, and emotional and physical reactions to certain sounds.1 Emotional, behavioral, and physiological reactions occur when exposed to certain sounds, and the misophonic reaction hurts the person's social, professional, and daily life.2,3 These triggering sounds are sounds produced by humans, especially oral and nasal sounds. Sounds such as chewing, slurping, breathing, keyboard sound or pen clicks can be given as examples.4 These sounds elicit certain negative emotional responses such as anger, irritation, disgust, and anxiety.5 Negative emotional reactions are accompanied by physiological reactions such as sweating, tachycardia, muscle tension, breathing difficulties, and pressure in certain areas or throughout the body.2 Emotional and physiological reactions may result in behavioral reactions such as verbal abuse, throwing objects, and physical aggression.6 However, the trigger sounds and the resulting reactions vary from person to person; therefore, learning is thought to play a role in the development of misophonia.4 Although not yet included in a formal psychiatric classification system, misophonia is being sought to be understood by psychiatric professionals due to the intense feelings of anger and anxiety that occur when exposed to trigger sounds, avoidance, and coping strategies similar to those seen in other mental disorders, and high rates of psychiatric comorbidity.7

Information on prevalence and associated factors in the general population is very limited. The prevalence of clinical symptoms of misophonia varies between 10 and 20% in studies conducted in samples such as students, hospital workers, and inpatient psychiatric patients.8 In a study conducted by Kılıç et al. with 541 individuals in Turkey, the prevalence of misophonia diagnosis was found to be 12.8%.7 It is thought which factors may play a role as risk factors for the development of misophonia. Although the risk factors associated with misophonia are not fully known, certain personality traits, genetic predisposition, neurobiological changes, and conditioning are risk factors for misophonia.1 Although studies on the nature of misophonia are limited, the disease hurts the social, professional, and daily life of the person and affects their functionality.2,3 The increasing number of individuals who self-identify as misophonia patients necessitate systematic studies to understand misophonia.9

This study aims to comprehensively review the literature on misophonia and identify the risk factors found in existing studies and their relationship with misophonia. Understanding the risk factors associated with misophonia will help provide an evidence-based basis for the development of methods that can be used in the treatment of the disease and will reveal gaps in scientific evidence that should be addressed in future research.

Materials and methodObjectiveThis systematic review aims to provide an overview of the results of observational studies that have investigated the factors associated with misophonia in the general or clinical population.

Search methodsA systematic literature search was performed between 15 March and 15 April to identify relevant studies published up to 15 April 2023, with no year limit. PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Taylor & Francis, and Science Direct electronic databases were searched using the keywords (“misophonia” OR “selective sound sensitivity syndrome” OR “sound intolerance” OR “sensory intolerance” OR “sound sensitivity” OR “decreased sound tolerance” OR “sound aversion” OR “aversive sounds” OR “trigger sounds”) AND (“predictors” OR “risk factors” OR “precipitating factors” OR “associated factors” OR “risk” OR “predisposing” OR “predisposing factor”). The keywords were determined by including the words that are frequently used for misophonia.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaThe inclusion criteria for this review are (1) articles in English, (2) case reports, case series, correlation studies, cross-sectional studies, case–control studies, cohort studies, (3) studies in which the symptoms of misophonia were assessed by a psychiatrist, (4) symptoms of misophonia assessed using a validated and standardized scale (e.g., MisoQuest, Amsterstam Misophonia Scale), and (5) articles involving symptoms of misophonia in the clinical or general population.

The exclusion criteria for this review are (1) qualitative studies, review articles, theses, dissertations, conference papers, and book chapters, (2) the study population consisted of children, and (3) studies in which only an audiologist assessed the symptoms of misophonia.

Search resultsAll references retrieved by the search strategies were exported using Endnote X9. Title/abstract screening was performed by two independent authors under the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Studies whose title/abstract did not fulfill the inclusion criteria were excluded at this step. Relevant articles were entered into an Excel-generated template for full-text readings and assessments. This template consisted of study details (authors, year of publication, country), inclusion or exclusion status, and reasons for exclusion. Searches of electronic databases resulted in 983 publications after duplicates were removed. After title/abstract screening, 28 full-text review articles were identified. Two independent authors (SK and GD) reviewed the full-text articles for data extraction, methodological quality assessment, and analysis. All discrepancies were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached. The screening process is given in a PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Data extractionA standardized data extraction form was used by two authors (SK and GD), which included several features. These were (1) authors, (2) year of publication, (3) country, (4) type of study, (5) sample characteristics/size, (6) assessment method used for measurements of symptoms and clinically meaningful misophonia, (7) misophonia-related factors, and (8) other important findings.

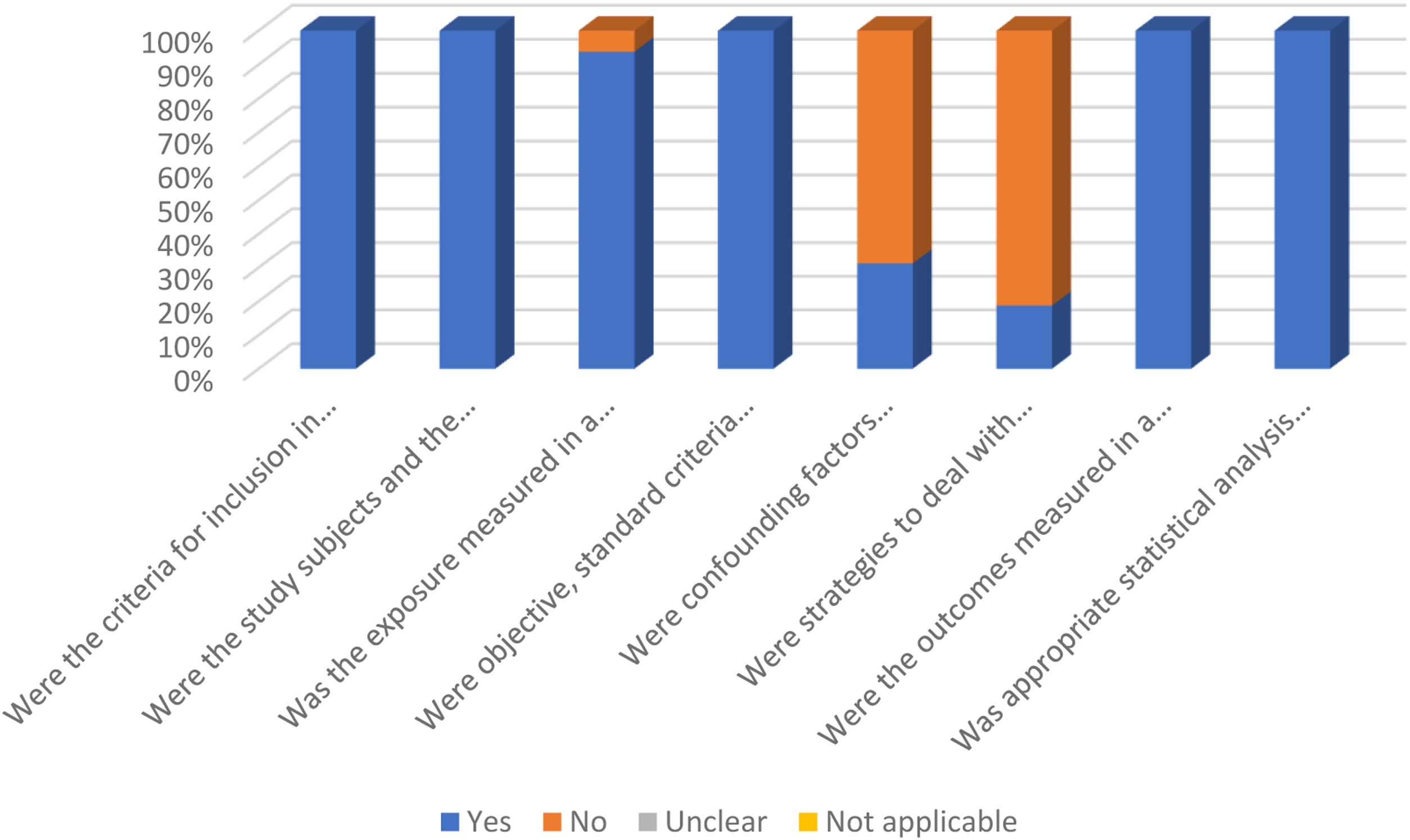

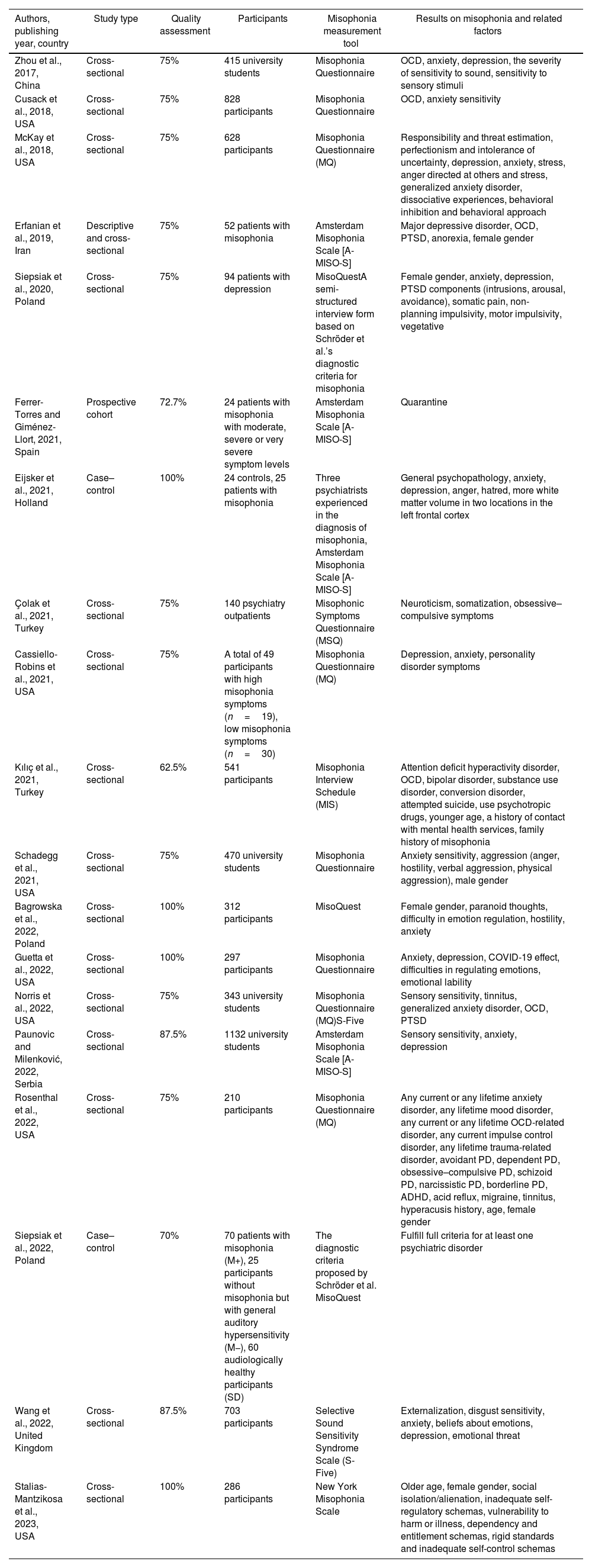

Quality assessmentJoanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical analysis tools were used for the quality assessment of the studies. “JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies” consisting of 8 items was used for quality assessment of cross-sectional studies. “JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Cohort Studies” consisting of 11 items was used for quality assessment of prospective cohort studies. “JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case-Control Studies” consisting of 10 items was used for the quality assessment of case–control studies. Each item in the checklists was coded as yes, no, unclear, or not/applicable.10 The quality assessment scores of the 19 included studies are presented in detail in Table 1

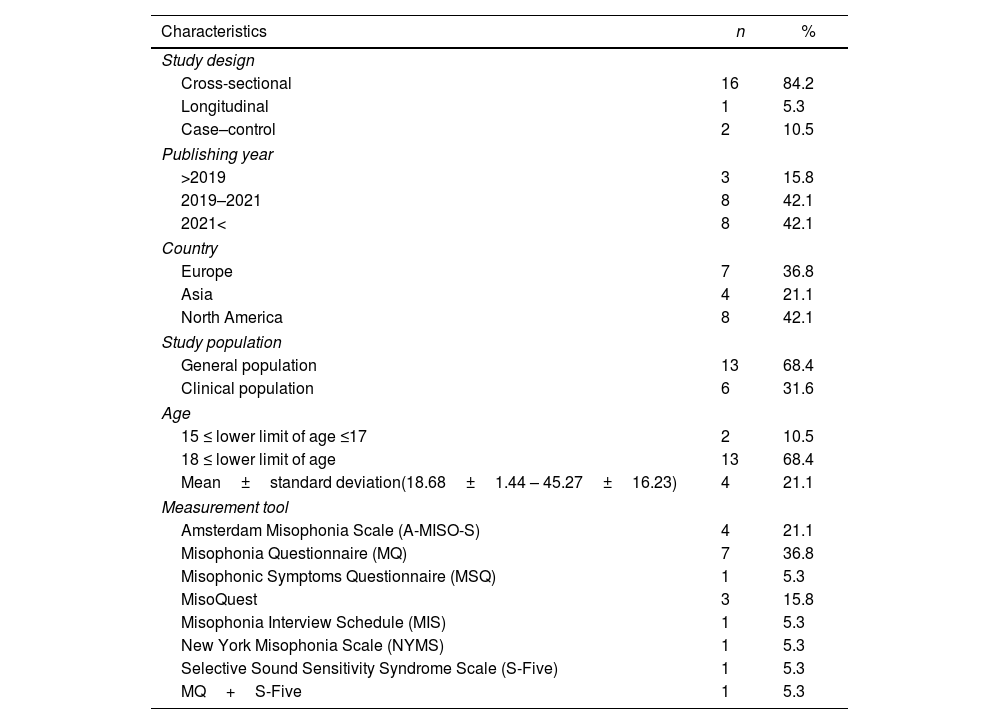

Characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review (n=19).

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Study design | ||

| Cross-sectional | 16 | 84.2 |

| Longitudinal | 1 | 5.3 |

| Case–control | 2 | 10.5 |

| Publishing year | ||

| >2019 | 3 | 15.8 |

| 2019–2021 | 8 | 42.1 |

| 2021< | 8 | 42.1 |

| Country | ||

| Europe | 7 | 36.8 |

| Asia | 4 | 21.1 |

| North America | 8 | 42.1 |

| Study population | ||

| General population | 13 | 68.4 |

| Clinical population | 6 | 31.6 |

| Age | ||

| 15 ≤ lower limit of age ≤17 | 2 | 10.5 |

| 18 ≤ lower limit of age | 13 | 68.4 |

| Mean±standard deviation(18.68±1.44 – 45.27±16.23) | 4 | 21.1 |

| Measurement tool | ||

| Amsterdam Misophonia Scale (A-MISO-S) | 4 | 21.1 |

| Misophonia Questionnaire (MQ) | 7 | 36.8 |

| Misophonic Symptoms Questionnaire (MSQ) | 1 | 5.3 |

| MisoQuest | 3 | 15.8 |

| Misophonia Interview Schedule (MIS) | 1 | 5.3 |

| New York Misophonia Scale (NYMS) | 1 | 5.3 |

| Selective Sound Sensitivity Syndrome Scale (S-Five) | 1 | 5.3 |

| MQ+S-Five | 1 | 5.3 |

The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1.

A total of 84.2% (n=16) of the analyzed studies were conducted in the last 5 years. A total of 84.2% (n=16) of the studies reported the research results with a cross-sectional design. The sample size was determined between 24 and 1132 participants. While 10.5% (n=2) of the studies reported the lower age limit of the participants in the sample as 15–17 years, 68.4% (n=13) reported the age as 18 years and above. A total of 21.1% of the studies reported the ages of the participants using mean and standard deviation. Among the included studies, 31.6% (n=6) were conducted in the clinical population and 68.4% (n=13) in the general population. The MQ was used to assess misophonia symptoms in 36.8% (n=7) of the studies.

The author, year of publication, country, type of study, quality assessments, sample characteristics/size, measurement tools, and results of the included studies are summarized in Table 2.

Coding table of included studies (n=19).

| Authors, publishing year, country | Study type | Quality assessment | Participants | Misophonia measurement tool | Results on misophonia and related factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhou et al., 2017, China | Cross-sectional | 75% | 415 university students | Misophonia Questionnaire | OCD, anxiety, depression, the severity of sensitivity to sound, sensitivity to sensory stimuli |

| Cusack et al., 2018, USA | Cross-sectional | 75% | 828 participants | Misophonia Questionnaire | OCD, anxiety sensitivity |

| McKay et al., 2018, USA | Cross-sectional | 75% | 628 participants | Misophonia Questionnaire (MQ) | Responsibility and threat estimation, perfectionism and intolerance of uncertainty, depression, anxiety, stress, anger directed at others and stress, generalized anxiety disorder, dissociative experiences, behavioral inhibition and behavioral approach |

| Erfanian et al., 2019, Iran | Descriptive and cross-sectional | 75% | 52 patients with misophonia | Amsterdam Misophonia Scale [A-MISO-S] | Major depressive disorder, OCD, PTSD, anorexia, female gender |

| Siepsiak et al., 2020, Poland | Cross-sectional | 75% | 94 patients with depression | MisoQuestA semi-structured interview form based on Schröder et al.’s diagnostic criteria for misophonia | Female gender, anxiety, depression, PTSD components (intrusions, arousal, avoidance), somatic pain, non-planning impulsivity, motor impulsivity, vegetative |

| Ferrer-Torres and Giménez-Llort, 2021, Spain | Prospective cohort | 72.7% | 24 patients with misophonia with moderate, severe or very severe symptom levels | Amsterdam Misophonia Scale [A-MISO-S] | Quarantine |

| Eijsker et al., 2021, Holland | Case–control | 100% | 24 controls, 25 patients with misophonia | Three psychiatrists experienced in the diagnosis of misophonia, Amsterdam Misophonia Scale [A-MISO-S] | General psychopathology, anxiety, depression, anger, hatred, more white matter volume in two locations in the left frontal cortex |

| Çolak et al., 2021, Turkey | Cross-sectional | 75% | 140 psychiatry outpatients | Misophonic Symptoms Questionnaire (MSQ) | Neuroticism, somatization, obsessive–compulsive symptoms |

| Cassiello-Robins et al., 2021, USA | Cross-sectional | 75% | A total of 49 participants with high misophonia symptoms (n=19), low misophonia symptoms (n=30) | Misophonia Questionnaire (MQ) | Depression, anxiety, personality disorder symptoms |

| Kılıç et al., 2021, Turkey | Cross-sectional | 62.5% | 541 participants | Misophonia Interview Schedule (MIS) | Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, OCD, bipolar disorder, substance use disorder, conversion disorder, attempted suicide, use psychotropic drugs, younger age, a history of contact with mental health services, family history of misophonia |

| Schadegg et al., 2021, USA | Cross-sectional | 75% | 470 university students | Misophonia Questionnaire | Anxiety sensitivity, aggression (anger, hostility, verbal aggression, physical aggression), male gender |

| Bagrowska et al., 2022, Poland | Cross-sectional | 100% | 312 participants | MisoQuest | Female gender, paranoid thoughts, difficulty in emotion regulation, hostility, anxiety |

| Guetta et al., 2022, USA | Cross-sectional | 100% | 297 participants | Misophonia Questionnaire | Anxiety, depression, COVID-19 effect, difficulties in regulating emotions, emotional lability |

| Norris et al., 2022, USA | Cross-sectional | 75% | 343 university students | Misophonia Questionnaire (MQ)S-Five | Sensory sensitivity, tinnitus, generalized anxiety disorder, OCD, PTSD |

| Paunovic and Milenković, 2022, Serbia | Cross-sectional | 87.5% | 1132 university students | Amsterdam Misophonia Scale [A-MISO-S] | Sensory sensitivity, anxiety, depression |

| Rosenthal et al., 2022, USA | Cross-sectional | 75% | 210 participants | Misophonia Questionnaire (MQ) | Any current or any lifetime anxiety disorder, any lifetime mood disorder, any current or any lifetime OCD-related disorder, any current impulse control disorder, any lifetime trauma-related disorder, avoidant PD, dependent PD, obsessive–compulsive PD, schizoid PD, narcissistic PD, borderline PD, ADHD, acid reflux, migraine, tinnitus, hyperacusis history, age, female gender |

| Siepsiak et al., 2022, Poland | Case–control | 70% | 70 patients with misophonia (M+), 25 participants without misophonia but with general auditory hypersensitivity (M−), 60 audiologically healthy participants (SD) | The diagnostic criteria proposed by Schröder et al. MisoQuest | Fulfill full criteria for at least one psychiatric disorder |

| Wang et al., 2022, United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 87.5% | 703 participants | Selective Sound Sensitivity Syndrome Scale (S-Five) | Externalization, disgust sensitivity, anxiety, beliefs about emotions, depression, emotional threat |

| Stalias-Mantzikosa et al., 2023, USA | Cross-sectional | 100% | 286 participants | New York Misophonia Scale | Older age, female gender, social isolation/alienation, inadequate self-regulatory schemas, vulnerability to harm or illness, dependency and entitlement schemas, rigid standards and inadequate self-control schemas |

OCD: obsessive–compulsive disorder; PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder; PD: personality disorder; ADHD: attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder.

Scores on the JBI critical analysis tools checklist ranged from 62.5% to 100%, with a mean score of 80.54±2.66%. The results of the quality assessment of the 16 cross-sectional studies included in the systematic review are presented in Fig. 2. Case–control studies were evaluated using the 10-item “JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case-Control Studies”, one of the studies was evaluated with 7 and the other with 10 yes responses. Cohort studies were evaluated using the “JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Cohort Studies” and 2 of the 11 items were evaluated with no, 8 with yes, and 1 with inapplicable.

Relationships between factors and misophoniaSociodemographic factorsThe included studies correlated participants’ sociodemographic factors such as age, gender, education level, occupational status, and marital status, with symptoms of misophonia.

In four of the studies, there was evidence that female gender was associated with the symptoms of misophonia.11–15 Paunovic and Milenković revealed that the female gender was protective against loss of self-control, a misophonic symptom.16 Schadegg et al., associated the male gender with higher misophonia symptom severity.17 In three of the studies did not find a relationship between gender and symptoms of misophonia.16,18,19 Eijsker et al., found that patients did not differ significantly in terms of female/male ratio compared to the control group.2 Although Kılıç et al., found that female gender was associated with higher rates of misophonia, misophonia was not associated with gender.7

In the studies reviewed, age was not a sociodemographic factor associated with misophonia symptoms.14,16,19 However, some studies reported an association of age with either misophonia or symptoms of misophonia. Some studies revealed that advanced age was the factor that increased the symptoms of misophonia.13,15 However, Kılıç et al., found that younger age was a predictor of misophonia.7

There was no correlation found between the level of education,2,18 marital status, and occupational status18 with the symptoms of misophonia. Although Kılıç et al., found that being unmarried was associated with higher rates of misophonia, misophonia was not associated with marital status.7

Mental disordersThe reviewed studies found significant and positive correlations between depressive symptoms, dysthymia, major depressive disorder, and the symptoms of misophonia.2,12–14,16,19–23 There were significant and positive correlations between anxiety symptoms, generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and symptoms, panic disorder, agoraphobia, social anxiety disorder, specific phobia and the symptoms of misophonia.2,7,11–14,16,18–25 The results showed significant associations between personality disorder symptoms and misophonia symptoms.13,20 Symptoms of misophonia are associated with substance use disorders,7 anorexia symptoms,12 dissociative experiences,22 attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, bipolar disorder, conversion disorder, and suicide attempt.7 However, Norris et al., found that the symptoms associated with misophonia were not associated with clinically significant levels of anxiety, depression, or personality disorder traits.25

Individuals with misophonia were found to be more likely than healthy individuals to meet diagnostic criteria for mental disorders.26 Stress, which is important for the development of mental disorders, showed an association with symptoms of misophonia.22

Factors associated with medical historyKılıç et al., found that a history of contact with mental health services, family history of misophonia, and use of psychotropic medication were associated with misophonia, whereas tinnitus was not.7 Rosenthal et al., found that self-reported history of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, migraine, acid reflux, tinnitus and hyperacusis, and impulse control disorder were positively associated with symptoms of misophonia, whereas a history of diabetes mellitus was negatively associated.13 Similarly, individuals with misophonia were found to experience more symptoms of tinnitus than those without.25

Misophonia severity was associated with COVID-19 and severe misophonia progressively reduced heart rate variability (HRV) after COVID-19 quarantine.27

Patients had neurological structural and functional abnormalities compared with controls. However, none of the structural or functional abnormalities showed a significant association with symptom severity of misophonia.2

Emotional factorsThe included studies found significant and positive associations between anger, hatred, anxiety sensitivity, difficulty in emotion regulation, hostility, emotional lability, emotional threat, and symptoms of misophonia.2,11,17,21–24

Cognitive factorsThe studies reviewed included somatization, paranoid thoughts, body-perceptual awareness and stress, intrusions and arousal related to disturbing memories, impulsivity and inability to plan, somatic pain, vegetative symptoms, early schemas – inadequate self-control, social isolation/alienation, vulnerability to harm or illness, high dependency, rigid standards, low self-righteousness, externalization, disgust sensitivity, beliefs about emotions, and symptoms of misophonia.11,14,15,18,22,23

Behavioral factorsThe included studies found significant and positive associations between aggression, behavioral inhibition, and behavioral approach, avoidance of reminders about disturbing memories, motor impulsivity, and symptoms of misophonia.14,17,22

Personality traitsThe studies reviewed found significant and positive associations between neuroticism, conscientiousness, threat anticipation, perfectionism, intolerance of ambiguity, and symptoms of misophonia.18,22

Sensory factorsSound sensitivity16,19 and sensitivity to sensory stimuli were significantly and positively correlated with the symptoms of misophonia.19 Sensory sensitivity was found to be higher in individuals with misophonia compared to those without.25

There was no significant difference in audiological functioning between the groups with and without misophonia.26

DiscussionThis review aimed to identify and categorize the factors associated with the symptoms of misophonia. The findings of our review showed that the most common sociodemographic factors and mental disorders were highlighted as factors associated with misophonia.

The fact that the compiled studies focus on different aspects of the symptoms of misophonia makes it difficult to interpret the results. Studies are showing that female gender is not differentiated according to gender as well as studies identifying female gender as a risk factor for misophonia symptoms. However, male gender is not a factor associated with symptoms of misophonia. Male patients find misophonia symptoms less distressing and are less susceptible to anxiety than female patients.12 Female patients show worse psychological and psychosomatic outcomes than male patients.1 These differences explain why female gender is a risk factor for misophonia. The reviewed studies do not show age as a risk factor for symptoms of misophonia. This finding is supported by the results of studies that did not find a significant relationship between age and the severity of misophonia symptoms.9,28,29 The finding by Kılıç et al., that young people have higher misophonia scores contradicts our study finding.7 However, the fact that the symptoms of misophonia are aggravated starting in childhood or adolescence and take a chronic course with advancing age explains the fact that age is not shown as a risk factor for misophonia.30 The reviewed studies do not show educational level, marital status, and occupational status as risk factors for symptoms of misophonia. Taylor et al., reported that those who reported being bothered by both tactile and auditory stimuli were more likely to be single and to have lower levels of occupational functioning than those who did not. This is because those who reported discomfort were less likely to be employed in full-time jobs and more likely to work in part-time jobs.31 Marital status shows a positive relationship with cognitive reappraisal. The process of misophonic response can be handled more positively or ineffectively with an emotion-regulating partner.32

The studies reviewed indicate that mental disorders are a risk factor for symptoms of misophonia. Depressive disorders and anxiety disorders are mental disorders with which the symptoms of misophonia are frequently associated. Existing studies reveal the association of misophonia with obsessive–compulsive disorder, anxiety, and depression.22,29,33 In depressive disorders and anxiety disorders, the limbic system seems to be more active. A more active limbic system may lead to auditory sensitivity in misophonia.34 Attention to detail and cognitive rigidity (the ability to selectively switch between thoughts in response to environmental demands) are observed in conditions such as perfectionism, depression, and OCD. In a study by Simner et al., attention to detail and cognitive rigidity were found to elicit the symptoms of misophonia.35 Specific hyperactivity of the anterior insular cortex, which directs attention to meaningful stimuli, is observed in misophonia.36 This neurological finding supports the relationship between attention and misophonia found by Simner et al. In this context, disorders such as depression and OCD, which increase attention to detail and cognitive rigidity, may have triggered attention to specific stimuli in misophonia. Psychopathological disorders associated with trauma may increase stress and reveal the misophonia response. Sounds accompanying the emotional stress states that occur with PTSD may lead to a misophonic response with negative reinforcement.37 A limited number of case reports and case series related to misophonia show that the use of antidepressants and anxiolytics provides an improvement in the severity of misophonia.38–40 This suggests that anxiety and depression may be risk factors for misophonia as well as comorbid diseases that exacerbate misophonia.

The reviewed studies show that a history of contact with mental health services constitutes a risk factor for misophonia. In individuals with a psychiatric diagnosis who use or have the potential to use mental health services, a high rate of comorbidity of misophonia and mental disorders has been reported.1 This finding suggests that it may increase the tendency to experience mental health problems and thus increase the risk of misophonia. In the present study, having a family history of misophonia was found to be a risk factor for misophonia. In the study by Smit et al., many single nucleotide polymorphisms (type of genetic variations) showed a significant effect on aversion to chewing sounds, which is a typical symptom of misophonia. The TENM2, TMEM256, NEGR1, and TFB1M genes were identified as candidate genes associated with significant effects.41 In the study by Sanchez and Silva, the high incidence of misophonia in a family including three generations indicated that the disease may have a hereditary etiology.42 These studies suggest that a family history of misophonia is a risk factor for the development of the disease because of the inherited or learned behavior of misophonia. In the studies reviewed, audiological disorders such as tinnitus and hyperacusis are risk factors for misophonia. The fact that misophonia can be treated with re-education therapy and voice therapy suggests that it may be an audiological disorder. However, it has been demonstrated that patients with misophonia typically have normal hearing thresholds.43,44 More studies are needed for tinnitus, hyperacusis as a risk factor because of the disagreement on whether misophonia is an audiological disorder.

The reviewed studies show that having difficulties in emotion regulation is a risk factor for misophonia. Emotion regulation is the ability to control, observe, evaluate, and change emotional reactions. With emotion regulation strategies, positive emotions are increased while negative emotions are decreased, and functionality and harmony are increased. Failures in emotion regulation lead to faster and more severe emergence of negative emotions such as anger, anxiety, and resentment, and difficulties in controlling them.45 Considering the emotional reactions such as anger, anxiety, and resentment to triggers, difficulties in emotion regulation may constitute a risk factor for misophonia. This inference is supported by study findings that emotion regulation difficulties are associated with misophonia.46

A review of studies suggests that somatosensory amplification is a risk factor for misophonia. Somatosensory amplification is an exaggerated awareness of physical sensations and perceptions in the body. Individuals with somatosensory amplification experience exaggerated physical sensations of misophonia, leading to worsening of the symptoms of misophonia. Emotional processing and cognitive control associated with the symptoms of misophonia are linked to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), hippocampus, and amygdala. The fact that the aforementioned brain areas are also linked to the neural network of somatosensory amplification, supports the relationship between misophonia and somatosensory amplification.18 The studies reviewed indicate that paranoid thoughts are also a risk factor. Individuals with misophonia who have paranoid thoughts may think that other people are malicious toward them or deliberately intend to cause disturbance because of the sounds around them. These paranoid thoughts may increase the emotional responses and intolerance levels of the misophonia. In a cross-sectional study investigating misophonia in a psychiatric population, the diagnosis of schizophrenia ranked second with 22.2%, indicating that paranoid thoughts may be a risk factor.9 The importance and control of thoughts, which can be seen in OCD, has been evaluated as a risk factor for misophonia. People experiencing misophonia show a continuous effort to follow, control, or concentrate on voices. This can create a kind of obsession with the person's thoughts about the voice, which may increase the symptoms of misophonia. In a study of patients with misophonia, 52.4% of the sample met the diagnostic criteria for obsessive–compulsive personality disorder, supporting our proposition.44 This supports the association between obsessive thought processes and misophonia. Identification of particular voices with past disturbing experiences or memories may pose a risk for misophonia. This results in an increased level of arousal with the unauthorized and unwanted intrusion of memories. The fact that triggers that are identified with specific memories may elicit a misophonic response suggests that childhood trauma may be a risk factor.47

In the studies examined, impulsivity is a risk factor for misophonia. The ability to plan and control reactions is associated with impulsivity and is inadequate in individuals experiencing misophonia. In the study involving more than three hundred misophonic participants, reports of impulsivity-related psychopathologies suggest that impulsivity influences the response to triggers.47

In the studies examined, neuroticism and perfectionism were found to be risk factors for misophonia. In a study by Daniels et al., neuroticism was found to contribute to high symptomatology of misophonia by leading to sensitivity to voices and emotional behaviors toward voices.48 Jager et al., found perfectionism and neuroticism in patients with misophonia in a study conducted with 575 subjects.30 In a study by Smit et al., it was found that stronger genetic correlations were observed in neuroticism/guilt and irritability/sensitivity cluster personality traits.41 These findings support our study results. Intolerance of ambiguity was found to be another risk factor for misophonia. Intolerance of uncertainty is the tendency to react negatively to uncertain situations. When the literature is examined, intolerance of uncertainty is a risk factor for obsessive–compulsive disorder.49,50 Because misophonia is evaluated within the scope of disorders related to OCD, intolerance of uncertainty may be a risk factor for misophonia. Responsibility and threat anticipation as a risk factor is the predisposition to feel responsible or to anticipate possible threats. These individuals may feel responsible when exposed to certain sounds or may be more prone to perceive these sounds as a threat. This, in turn, may contribute to an increase in the symptoms of misophonia.22

In the studies examined, one of the risk factors associated with misophonia is sensitivity to sensory stimuli. It is thought that the pathways responsible for sensory hypersensitivity may be impaired in misophonia in individuals who report clinically significant symptoms of misophonia.25 In this context, impairment in the neural pathways responsible for sensitivity to sensory stimuli may lead to misophonia.

Methodological considerationsThe strengths of this systematic review are the different studies included to collect, analyze and synthesize risk factors associated with misophonia. This was achieved through the inclusion of alternative terms associated with misophonia and the lack of time limitation. With this study, the synthesis of the existing literature has been provided to the literature related to misophonia. However, this study has some limitations. The inclusion of only English-language articles increases the risk of missing studies in other languages. Associated risk factors may have an underestimated or overestimated effect on the topic under investigation. Secondly, 84.2% of the studies have cross-sectional designs, which makes it difficult to determine causality. In addition, different self-report scales were used in the included studies. These scales focused on different aspects of misophonia due to the lack of consensus on the diagnostic criteria for misophonia.

Directions for future researchThis study has revealed possible risk factors for misophonia. In the future, prospective cohort studies should be designed to evaluate causal relationships. Although it is known to be common, it has been studied with small samples. Larger samples should be used to understand the factors associated with misophonia and for more reliable results. Self-report scales are used to determine misophonia. Future research should focus on the development of methods that can objectively measure misophonia. For example, methods such as examining brain activities associated with misophonia using brain imaging techniques or using biological indicators to measure physiological responses can be evaluated.

ConclusionThis study provides an overview of the evidence on factors associated with misophonia in individuals aged 15 years and older in the general or clinical population. Several risk factors associated with misophonia have been identified. These risk factors may have an impact on the occurrence, severity, and effects of misophonia symptoms. However, most risk factors have been reported by one or two studies with cross-sectional designs. Gender and mental disorders are frequently reported as risk factors. Medical history, emotion, cognition and behavior, personality traits, and auditory hearing factors associated with misophonia have been addressed less frequently. In this study, it is known that chronic illnesses associated with misophonia cause people to experience emotional and psychological difficulties in managing their situations and increase their stress levels.51 Considering that increased stress levels may exacerbate the symptoms of misophonia, it is important to evaluate and treat comorbidities. Thus, a holistic treatment approach can be adopted by focusing on the general health status of patients.

Author's contributionsSK: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, visualization, writing – original draft. GD: project administration, conceptualization, supervision, writing – review & editing.

FundingThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no competing interests to declare.