Although the validation of widely used scales measuring psychological constructs in various cultural and linguistic settings is important, such as the Self Stigma of Seeking Help (SSOSH) scale administered in the university students of the Colombian health sector,1 we still know little about the responses of populations, other than the adult population of students which create problems of generalizability in psychological research designs.2 More specifically, we ignore the older adults’ population.3 Therefore, the aim of this study is to bring attention to a question regarding the influence of basic demographics such as age, gender, education and general cognition on the self-stigma associated with seeking professional help in older adults.

For this reason, the Greek version of SSOSH was used4 (see Table 1), this time administered exclusively to older adults aged 65 and over (n=148 older adults from Northern Greece; 87 women and 61 men; mean age, 74.18±4.87 years; mean education, 9.62±3.64 years) who participated voluntarily. Along with the SSOSH (the internal consistency of the SSOSH was α=.69), Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) was also administered in order to measure general cognition (mean, 27.91±1.68),5 as well as the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale whith a cut-off 6/7 point applied for diagnosing depression6 (mean, 1.54±1.58; minimum GDS score, 0; maximum GDS score, 5). The community dwelling participants in this sample were all native Greek speakers and did not have at the time of the examination a formal diagnosis of psychiatric disease (e.g. clinical depression, neurocognitive disorders, etc.). The participants were blind regarding the results of their neuropsychological examination.

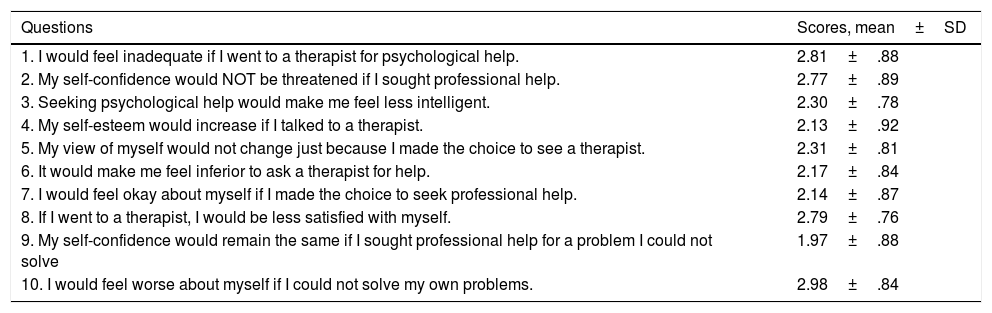

Self-Stigma of Seeking Psychology Help (SSOSH).

| Questions | Scores, mean±SD |

|---|---|

| 1. I would feel inadequate if I went to a therapist for psychological help. | 2.81±.88 |

| 2. My self-confidence would NOT be threatened if I sought professional help. | 2.77±.89 |

| 3. Seeking psychological help would make me feel less intelligent. | 2.30±.78 |

| 4. My self-esteem would increase if I talked to a therapist. | 2.13±.92 |

| 5. My view of myself would not change just because I made the choice to see a therapist. | 2.31±.81 |

| 6. It would make me feel inferior to ask a therapist for help. | 2.17±.84 |

| 7. I would feel okay about myself if I made the choice to seek professional help. | 2.14±.87 |

| 8. If I went to a therapist, I would be less satisfied with myself. | 2.79±.76 |

| 9. My self-confidence would remain the same if I sought professional help for a problem I could not solve | 1.97±.88 |

| 10. I would feel worse about myself if I could not solve my own problems. | 2.98±.84 |

SD: standard deviation.

Items 2, 4, 5, 7, and 9 are reverse scored for this scale.

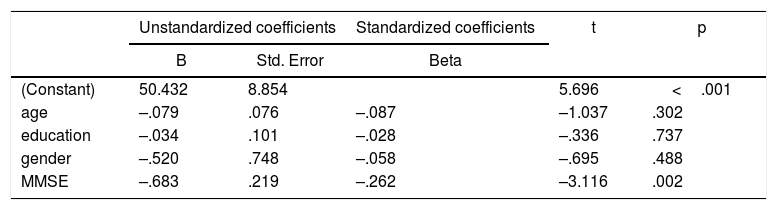

Linear regression model, “Enter” method indicated that among the demographic variables (age, gender, education years) none predicted SSOSH and that only MMSE total score predicted SSOSH (R=.276; R2=.076) (table 2). The low value of R2 should be approached with caution, since this indicates that the independent variable (MMSE) is not explaining in a great extent the variation of the dependent variable (SSOSH), regardless of the variable significance, but in our case the identified independent variable is of importance as it is studied for the first time in this exploratory research and could be used among other new variables in future research attempts.

Results from regression analysis for several predictors of self-stigma of seeking psychology help.

| Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | |||

| (Constant) | 50.432 | 8.854 | 5.696 | <.001 | |

| age | –.079 | .076 | –.087 | –1.037 | .302 |

| education | –.034 | .101 | –.028 | –.336 | .737 |

| gender | –.520 | .748 | –.058 | –.695 | .488 |

| MMSE | –.683 | .219 | –.262 | –3.116 | .002 |

Dependent variable: SSOSH

Compared with older men, older women did not show that they perceived less public-stigma and self-stigma as shown in previous studies in young adults, and more favorable attitudes to seeking psychological help.4 Of course, the results did not show any statistically significant differences between men and women regarding other demographic variables such as their age [t(146)=.565; P=.573], education [t(146)=.133; P=.894], and MMSE [t(146)=.035; P=.972], that could influence SSOSH when gender differences are under discussion [t(137)=.695; P=.488].

The importance of cognitive factors such as general cognition measured with MMSE is established for the first time in research exploring self-stigma for psychological help.7 MMSE asks questions to ascertain cognitive status and it is of interest that the participants with higher self-stigma had lower MMSE scores as those that are afraid that there is a problem with their cognitive performance may wish to avoid medical/psychological/psychiatric settings even if there is no diagnosis related to cognitive deficits for them so far. Future research should further examine this psychological variable in the light of the influence that individual emotional correlates and family/social relationships may have on the perception of stigma when seeking for help along with other cognitive variables such as metacognition.8,9

Conflicts of interestsNone.