Numerous studies have addressed the dynamics of bacterial communities in response to remediation strategies, while fungal communities, despite their potential as bioremediation agents, remain comparatively understudied. The aim of this work was to evaluate the impact of wheat straw amendment (WSA) on an oily sludge untreated and treated with ammonium persulfate on indigenous mycobiota after 60 days. Culture-independent 18S rRNA amplicon sequencing, microbial enzymatic activity and chemical parameters were analyzed. WSA on a preoxidized oily sludge promoted high total petroleum hydrocarbon (TPH) removal after 60 days, exhibiting the highest laccase activity. Fungal diversity and equitability were also recovered until reaching similar index values to those of the untreated microcosms. However, changes in fungal taxonomical groups were detected, with Eurotiales (93.4%) being replaced by Microascales (57.9%) and Sordariales (32.8%) at the end of the treatment. Our results suggest that inputs of easily assimilable organic matter in oily sludge might accelerate changes and replacement of fungal taxa, also affecting microbial colonization and, consequently, pollutant removal. These findings highlight the relevance of incorporating fungal dynamics into bioremediation strategies as a complementary approach to oily sludge treatment.

Numerosos estudios abordan la dinámica de las comunidades bacterianas en respuesta a las estrategias de remediación, mientras que las comunidades fúngicas, a pesar de su potencial como agentes de biorremediación, siguen siendo comparativamente poco estudiadas. El objetivo de este trabajo fue evaluar el impacto de la enmienda de paja de trigo en un barro oleoso no tratado y tratado con persulfato de amonio sobre la micobiota indígena después de 60 días. Se analizaron la secuenciación del amplicón 18S rRNA, la actividad enzimática microbiana y los parámetros químicos. La enmienda de paja de trigo sobre un barro oleoso preoxidado promovió una elevada eliminación de hidrocarburos totales del petróleo (HTP) después de 60 días, mostrando la mayor actividad de lacasa. La diversidad fúngica y la equitatividad también se recuperaron hasta alcanzar valores de índice similares a los microcosmos no tratados. Sin embargo, se detectaron cambios en los grupos taxonómicos fúngicos, siendo Eurotiales (93,4%) reemplazados por Microascales (57,9%) y Sordariales (32,8%) al final del tratamiento. Nuestros resultados sugieren que la entrada de materia orgánica fácilmente asimilable en un barro oleoso podría acelerar los cambios y la sustitución de los taxones fúngicos, afectando también a la colonización microbiana y, en consecuencia, a la eliminación de contaminantes. Estos hallazgos destacan la relevancia de considerar la dinámica de la micobiota nativa en las estrategias de biorremediación, lo que podría dar lugar a una estrategia complementaria en el tratamiento de barros oleosos.

During the upstream and downstream operations of the oil industry, such as extraction, transport, storage and refining of crude oil, huge amounts of oily sludge wastes are generated. The global crude oil production was 4.4 billion metric tons in 202238, and the annual production of oily sludge in the world was approximately 2.23×1010kg42. This type of residue is classified as a priority environmental pollutant by the US Environmental Protection Agency43. According to the refinery process applied and its source, oily sludge is classified into four types: landing sludge, drilling sludge, refinery sludge and tank bottom sludge42. In composition, oily sludge consists of a complex emulsion of petroleum hydrocarbons (PH) including aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons, nitrogen, sulfur and oxygen-containing compounds, resins and asphaltenes, as well as water, heavy metals and different solid particles42.

Before their final disposal, oily sludges must be properly treated to meet the waste disposal standards established by numerous global20 and current local regulations13. Among the feasible strategies, chemical oxidation using oxidizing reagents, such as persulfate anion27, Fenton's reagents37 and ozone11, have shown promising results for oily sludge treatment. However, it negatively impacts on the concentration level of the native soil microbiota, affecting soil functionality. Bioremediation strategies, such as bioaugmentation19,28 biostimulation32 and composting2, have also been successfully used for treating oily sludge. Since each of these techniques has limitations (e.g., environmental factors, contaminant bioavailability, among others) the scope of bioremediation solutions is still limited.

Recent research has shown that the combination of chemical and biological treatments might provide greater efficiency than individual processes, including the improvement of contaminant removal rates. While the application of chemical oxidants reduces pollutant charge and increases contaminant bioavailability, it also severely affects the indigenous soil microbiota and the ecological properties of the polluted matrix1,48. Interestingly, the sequential application of chemical oxidation followed by bioremediation strategies in chronically PAH-contaminated soils have been shown to improve hydrocarbon removal rates, reducing the toxicity generated by chemical reagent application and promoting native microorganisms7. Several bioremediation studies, such as biostimulation46, biaugmentation21 and composting25 have been successfully coupled after chemical pretreatments of chronically contaminated soils. Although many studies have addressed the effect of these combined strategies on soil pollutant removal rates and variations of bacterial community diversity, limited research has been conducted on their effects on the fungal community structure and diversity in oily sludge4,28. Fungi are one of the most abundant microorganisms in biomass in terrestrial ecosystems that play a fundamental role in the decomposition of organic matter40. Promoting the generation of new microenvironments for other organisms in anthropically impacted ecosystems, the ecological assessment of other microorganisms other than bacteria, such a as fungi, must not be ignored10,50. The relatively non-specific metabolism of most fungi colonizing heterogeneous matrices such as soil, litter and organic residues, together with their high ecological versatility and adaptation to adverse environmental conditions, provides promising potential for the biodegradation of organic pollutants by them10.

Lladó et al.24 reported that the biostimulation strategy using lignocellulosic substrates is key to enhancing the activity and resilience of native fungi in contaminated soils and the removal of high molecular weight PAH. Furthermore, numerous fungal taxa have been isolated from contaminated sites and studied for their ability to use petroleum hydrocarbons as unique carbon source3.

In this context, it is hypothesized that biostimulation of oily sludge pretreated with ammonium persulfate, through the addition of a model lignocellulosic substrate such as wheat straw, may modify the mycobiota structure, promoting additional petroleum hydrocarbon removal. This study aims to assess the impact of wheat straw amendment on both untreated and ammonium persulfate-treated oily sludge, focusing on the changes in the indigenous mycobiota after 30 and 60 days of incubation.

The following variables were assessed: hydrocarbon concentration, enzymatic activity related to the action of bacteria and fungi and fungal community diversity and structure (18S rRNA amplicon sequencing). The relationship between fungal taxa, based on the principles of fungal ecology, as well as their persistence in the polluted matrix across the monitoring period, are also discussed.

Materials and methodsOily sludgeThe oily sludge used in this study was collected from an API (American Petroleum Institute) separator during wastewater treatment at a petroleum refinery located in La Plata city, Buenos Aires, Argentina (34°53′19′′S, 57°55′38′′W). It was characterized based on its total petroleum hydrocarbon composition, SARA fractions (saturates, aromatics, resins, and asphaltenes)8, heavy metals by acid pre-digestion with nitric acid using microwaves (Questrom Technologies Corp.) and quantitation using an atomic emission spectrometer (Shimazdu ICPE-9800) according to the standard method EPA 601045.

Oxidative pretreatment of the oily sludgeThe oxidative pretreatment was conducted in a batch setup by applying ammonium persulfate (PSA) (Merck) at 10% p/p to the oily sludge. PSA was activated with Fe (II)26 in a 25% p/v aqueous solution. Three successive additions of the PSA solution were conducted by aspersion26 to reach a PSA final concentration of 120g per kg of dry oily sludge (OS). The assay was performed in triplicate. After each PSA application, the systems were homogenized and incubated at 30°C in the dark for 20 days. Finally, the residual concentration of PSA in the oxidation systems was determined27. The oxidized OS was successively used for the microcosm set up.

Microcosm setupA microcosm experiment was performed in 200ml glass jars with lids. Two conditions were assessed: the OS treated with ammonium persulfate oxidant (referred to as APT) and the control of untreated OS (referred to as UT). In both cases, the OS was mixed with calcined sand in a 3:1 w/w proportion to facilitate sludge manipulation. Each microcosm containing 20g of the OS-sand mix was then amended with 2g of sterile wheat straw, and water content was adjusted to 70% with distilled water. In addition, the pH decrease caused by ammonium persulfate was regulated to 7.7 with the addition of 1g of crushed clamshell in the APT microcosms. Microcosms were independently conducted in triplicate and incubated in the dark at 28°C for 30 and 60 days under static conditions without additional aeration system. The initial sampling at time 0 was performed immediately after setting up the microcosms. Sampling was destructive at each time point and the content of each microcosm was processed using a hand mixer (Philips 300W) to fully homogenize the sample. The total number of microcosms was 18 (2 conditions×3 replicates×3 sampling times).

Hydrocarbon contentsTotal petroleum hydrocarbon (TPH) content was estimated at 0, 30 and 60 days by solvent extraction followed by FTIR quantification. Chemical extraction was performed using five grams of dried sample and 20ml of perchloroethylene (Anedra) under ultrasonication (1 cycle of 1h). Solvent extracts were cleaned up with 1g of silica gel 60 (0.063–0.200mm; AppliChem GmbH). The absorbance of the extracts was measured in a quartz cell (1cm path-length) in a FTIR spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific Nicolet 200), and data was analyzed with the EnCompass software. Absorbance limits were defined between 400 and 4000cm−1, considering the peak height at 2950cm−1 as the TPH concentration44. Calibrations were performed from an oil mixture of n-hexadecane and isooctane according to the validated intern protocol PE-01.

For aliphatic hydrocarbons (AH) and PAH determinations, the ultrasonic extraction EPA SW-846 Method 3550C43 was used. A 2.5g sample was mixed with 5g of anhydrous sodium sulfate, and three sequential extractions were performed with 15ml of hexane/acetone 1/1 (vv−1). Hydrocarbons were extracted in an ultrasonic bath (Testlab Ultrasonic TB10TA) at 40kHz, 400W for 60min1. Sample extracts were then centrifuged at 4000rpm for 10min (Presvac model DCS-16 RV) and supernatants were collected in glass containers for evaporation. The solid extract was resuspended in 1ml of hexane and filtered using a nylon membrane of 0.45-μm pore size, and then, transferred into vials for injection into a Perkin Elmer Clarus 500 gas chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector. Finally, samples were analyzed as proposed by Agnello et al.1.

Enzymatic assaysDehydrogenase and laccase enzymatic activities were assessed at 30 and 60 days. Dehydrogenase and laccase enzymes were used as indicators of native microbial metabolic and fungal activity, respectively. The dehydrogenase activity was measured by the colorimetric reaction (546nm) of the reduction of 2,3,5-triphenyl-2H-tetrazoliumtrichloride [TTC] to triphenyl formazan [TPF]1. Laccase was extracted from samples as described by Ruiz-Hidalgo et al.33 using ABTS [2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)] as substrate of the oxidizing reaction. Laccase (EC 1.10.3.2) activity was measured by using 50mM – ABTS (Sigma) in 500mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5); ɛ436=29, 3mM−1cm−134.

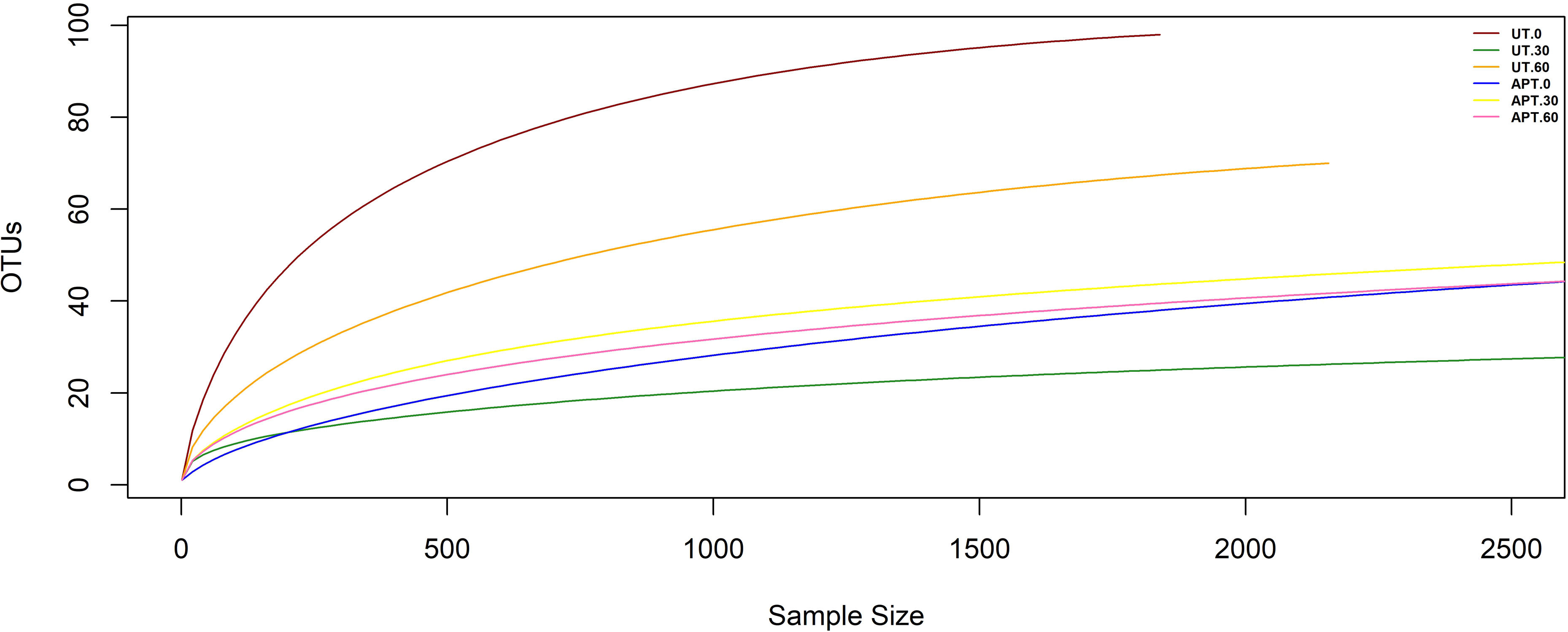

DNA extraction, 18S rRNA amplicon sequencing and bioinformatic analysesTotal DNA was extracted from 1g of mixtures containing oily sludge from each microcosm at 0, 30 and 60 days, using the E.Z.N.A Soil DNA kit (OMEGA, United States) according to the manufacturer's protocol. DNA extracts were checked for quantity and quality using a NanoDrop™ 2000/2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and stored at −20°C until further analysis. The DNA extracts from the biological triplicates were pooled into a single representative sample before being amplified and sequenced. The similarity between biological replicates was previously verified by PCR-DGGE, showing a similar banding pattern (data not shown). The PCR amplification of the 18S rRNA gene region was performed with primers euk1391F (GTACACACCGCCCGTC) and EukB-Rev (TGATCCTTCTGCAGGTTCACCTAC)39 and subsequently submitted to the sequencing platform Mr. DNA (Molecular Research LP, Shallowater, TX). This service provides reliable results as reported in numerous comparable studies12, including investigations focused on fungi47. Therefore, DNA amplification, library preparation and sequencing in the Illumina MiSeq platform were performed according to Mr. DNA guidelines. Quality filtered sequences were processed through chimeric read removal algorithms using USEARCH v11.0.667. The sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 97% using the USEARCH/UPARSE algorithm. The taxonomic assignment was carried out using SILVA database V138 with a cut-off=80 by the VSEARCH algorithm. Manual validation of the OTUs by examining the taxonomy assignment values was conducted6. Rarefaction curves were constructed (Fig. 1). The OTUs table was normalized with the minimum number of reads per sample and used to calculate diversity indices (Good, Shannon, Chao, Simpson inverse), and estimate beta-diversity through principal-coordinate analysis (PCoA) on Bray-Curtis distances tested for significance using the PERMANOVAR method. Graphic visualization was performed in R Studio software (2023.03.0 Build 386) using the Phyloseq package.

Raw sequence data is archived in the repository of Sequence Read Archive (SRA) – National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Bioproject ID is: PRJNA1010162 and BioSample accession numbers are: SAMN37181967, SAMN37181968, SAMN37181969, SAMN37181970, SAMN37181971 and SAMN37181972.

Statistical analysesUnless otherwise specified, significant differences among the samples were conducted by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey's test in the InfoStat software (version 2008)14.

ResultsThe oily sludge used in this study was a semi-liquid mixture, mainly composed of soil particles and other solid materials (70%), containing a high amount of TPH (193.054±16.082mgkg−1 according to the IR analysis). These latter compounds were represented by 64% of maltenes (AH, PAH and type II resins), 34% of type I resins and 2% of asphaltenes according to the SARA fractionation, respectively. Table 1 shows the physical and chemical properties determined on the oily sludge, including metal concentrations of Ni, V and Fe, with the latter exhibiting the highest value.

Physicochemical properties of oily sludge used in this study.

| Parameter | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Color | Dark brown-black | ||

| Smell | Sulfur-hydrocarbons | ||

| Appearance | Oily-viscous | ||

| Water solubility | Topoily-phase | Intermediatewater-phase | Bottomsediment phase |

| Water saturationa | 16±3 | ||

| pH | 5.6±0.1 | ||

| Electrical conductivity (dS/m)b | 1.1±0.1 | ||

| Redox potential (mV) | 173±17 | ||

| Total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH – mgkg−1) | 193.054±16.082 | ||

| Maltene (AH, PAH and type II resins)% | 64 | ||

| Type I resins% | 34 | ||

| Asphaltenes% | 2 | ||

| Ni (mgkg−1)c | 101 | ||

| V (mgkg−1)c | 45 | ||

| Fe (mgkg−1)c | 21599 | ||

The oxidative pretreatment of the oily sludge with ammonium persulfate significantly reduced the (Bilateral t Student's test t=5.54; p=0.0052) TPH concentration to 132.872±9.765mgkg−1 (31±5%). The wheat straw amendment treatment, either untreated (UT) or treated with ammonium persulfate (APT), produced a further reduction of the TPH content by 18 and 30% respectively, after 60 days of incubation and compared to the initial concentration (Table 2). However, the PAH content was only reduced in samples whose oily sludge had been previously exposed to the ammonium persulfate treatment, such as those found after 30 and 60 days of incubation. A differential behavior was found in the content of AH throughout the incubation with the wheat straw amendment. Although the content decreased by 80% after 30 days in samples with untreated sludge, it increased again after 60 days of incubation. This behavior may be attributed to the transformation of the wheat straw amendment by the native microbiota24. Those samples that contained sludge treated with ammonium persulfate reduced the content of AH both after 30 and 60 days of incubation.

Impact of oxidative and amended treatment on total hydrocarbons (HT), aliphatic (AH) and aromatic (PAH) and enzymatic activity in oily sludge microcosms at 30 and 60 days.

| TPH(mgkg−1) | AH(mgkg−1) | PAH(mgkg−1) | Dehydrogenase activity(μg TPF/gdry) | Laccase activity (mU/gdry) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UT | 0 | 135.881±19.688a | 2.856±212bc | 85±4 | – | – |

| 30 | 157.447±11.222ab | 567±63c | nd | 100±5c | 52±54b | |

| 60 | 111.003±7.323bc | 2.069±1.838bc | 54±45 | 44±29c | nda | |

| APT | 0 | 116.268±3.845bc | 3.619±224b | 135±27 | – | – |

| 30 | 97.903±7.599cd | 1.705±417bc | 74±8 | nda | 633±75c | |

| 60 | 81.830±2.550d | nda | nd | 4±2b | 435±155c | |

Dry weight corresponding to mass units per system. For the same parameter, the mean values followed by different letters are significantly different (p>0.05). Test: Tukey Alfa=0.05. HA and PAH-ANOVA one way. nd: not detected; UT: untreated treatment; APT: ammonium persulfate treatment.

The activity of two specific enzymes was measured after 30 and 60 days (Table 2). After 30 days, the UT microcosms showed an average value of dehydrogenase activity of 100μg TPFg−1 of dry sludge, with no significant difference detected after 60 days. Conversely, and independently of the incubation days, a reduction in the levels of this activity was observed when the sludge was previously treated with ammonium persulfate. Laccase activity was only detected after 30 days of incubation in the UT microcosms. Notoriously, the effect of the wheat straw amendment was higher in the treated microcosms than in the untreated microcosms.

A culture-independent approach of 18S rRNA amplicon sequencing was conducted to analyze the impact of the treatments on the indigenous mycobiota from the oily sludge used. Massive sequencing provided 516410 sequences that, after filtering based on quality, algorithms and reference databases as described above, were reduced to 498253. These sequences were clustered into 864 OTUs, with 152 assigned to fungi and 98 removed as chimeric sequences. The rarefaction curves of the samples reached a plateau, suggesting a good representation of the fungal community (Fig. 1).

Table 3 shows, for each treatment, the number of total sequences after filtering, the number of fungal assigned OTUs and the alpha diversity indices.

Number of nucleotide sequences obtained from 18S rRNA amplicons, OTUs observed and alpha diversity indices.

| Treatment | Time (days) | Sequences | Fungal OTUs | Chao1 index | Shannon index | Inv. Simpson index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UT | 0 | 1839 | 97 | 100.9 | 3.11 | 8.84 |

| 30 | 67607 | 66 | 111.3 | 1.48 | 2.99 | |

| 60 | 2156 | 69 | 74.8 | 2.31 | 5.42 | |

| APT | 0 | 36217 | 83 | 85.5 | 0.61 | 1.23 |

| 30 | 12930 | 70 | 85.6 | 1.46 | 2.34 | |

| 60 | 26710 | 72 | 83.2 | 1.52 | 2.65 | |

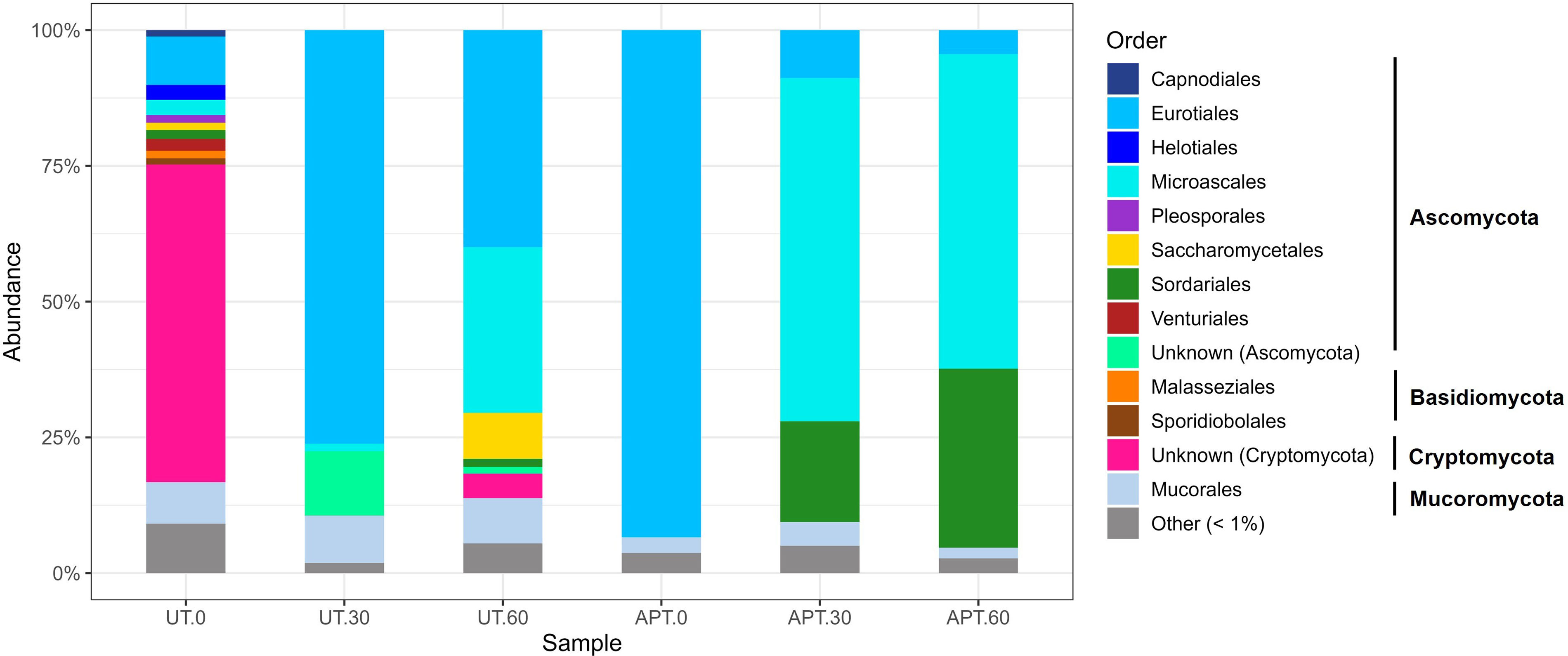

In addition, Figure 2 shows the taxonomic profiles of the fungal community, identifying several orders belonging to Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Cryptomycota and Mucoromycota phyla in the UT and APT microcosms during the incubation time.

Fungal taxa belonging to phylum Cryptomycota (61%), Ascomycota (26%) and Mucoromycota (8%) were dominant in the UT. The phylum Cryptomycota was represented by environmental sequences affiliated with the LKM11 class, which include unculturable fungi. In addition, the phylum Ascomycota was represented by members of the order Eurotiales (9%), while the phylum Mucoromycota, by members of the order Mucorales (7.7%). Members of Aspergillaceae with the genus Aspergillus (50.6%) and Trichocomaceae with Talaromyces (24.8%) were the most abundant in the untreated sludge microcosm after 30 days. However, the abundance of Aspergillus representatives decreased after 60 days, at which point the members of Microascaceae/Scedosporium boydii (30.5%) were the most dominant.

Concomitantly, a decrease in richness and diversity was observed in the UT microcosms after 60 days of incubation.

The effect of the oxidative treatment was revealed in the reduction of fungal diversity indices. Diversity and equitability indeces showed more of an impact from the ammonium persulfate treatment. Members of the Ascomycota order were the most prevalent among the orders found in the APT-0 microcosms. After that, the Chao1 index was maintained constant throughout the incubation period. Species diversity and equitability also recovered until reaching index values similar to those of the UT microcosms after 60 days.

The loss of fungal richness relative to the initial taxa detected in APT microcosm led to a community dominated by Eurotiales (93.4%). After 30 and 60 days of incubation with wheat straw, a sharp decline in the relative abundance of this fungal order was observed, being replaced in greater proportion by S. boydii (Microascales) (63.2–57.9% respectively) and to a lesser extent by Humicola fuscoatra (Chaetomiaceae) (18.5–32.8% respectively).

DiscussionThe oxidative treatment of the oily sludge with ammonium persulfate caused 31% TPH removal. The supplementation of wheat straw to this preoxidized matrix, which enabled the activity of microbial community, stimulated further TPH elimination. Given the low dehydrogenase activity, the decrease in TPH could be attributed mainly to the action of native fungi, corresponding to a high laccase activity, such as Lladó et al.24 has also suggested. This behavior supports the proposal that the native mycobiota includes numerous members capable of synthesizing laccases and other oxidative enzymes, as has been reported for several members of the phylum Ascomycota, which are active in the transformation and degradation of PAH in soil36.

It is probable that the changes produced by the oxidative treatment in the oily sludge enabled the colonization and activation of the tolerant mycobiota to exploit new resources, such as metabolites generated by the action of APS, which might have been easily assimilated by certain groups of fungi.

Of the total of 864 OTUs inferred, only 152 were assigned to fungal sequences. However, this study showed changes in the fungal composition by two treatments: oxidative stress and biostimulation. Similarly to previous studies, the oily sludge used showed a dominance of Cryptomycota representatives affiliated with the environmental clade LKM11, which belongs to the so-called “dark matter fungi” (DMF) and have not yet been cultured and is missing from current taxonomies of the fungal kingdom22,29,30. However only a slight part (0.9% on average) of fungal soil communities at the world scale are assigned to this phylum,41 which have been associated to metal (Zn, Pb) contaminated sites22 and activated sludge systems29. Importantly, aquatic habitats have been reported to harbor numerous taxa of Rozellomycota (Cryptomycota), which affect remineralization and fluxes of nutrients and organic matter in aquatic environments18. These fungi are obligated parasites of a variety of hosts in Oomycota (Heterokontophyta), the green alga Coleochaete (Charophyta) and fungi, specifically in the phyla Blastocladiomycota, Monoblepharidomycota, Chytridiomycota, and Basidiomycota23. In line with this, OTUs corresponding to Basidiomycota and Blastocladomycota were detected in the UT treatment at T0, at a proportion lower than 1%. Therefore, Cryptomycota found in sediments, as reported by Rojas-Jimenez30 for Antarctic lakes, could be key in the modulation of the structure and complexity of specific microbial communities17. Another fungal group representative in the OTUs identified in our study was phylum Ascomycota, where the order Eurotiales was dominant. Numerous genera such as Aspergillus and Penicillium, have been isolated from contaminated sites and studied for their ability to metabolize petroleum hydrocarbons as a sole source of energy3.

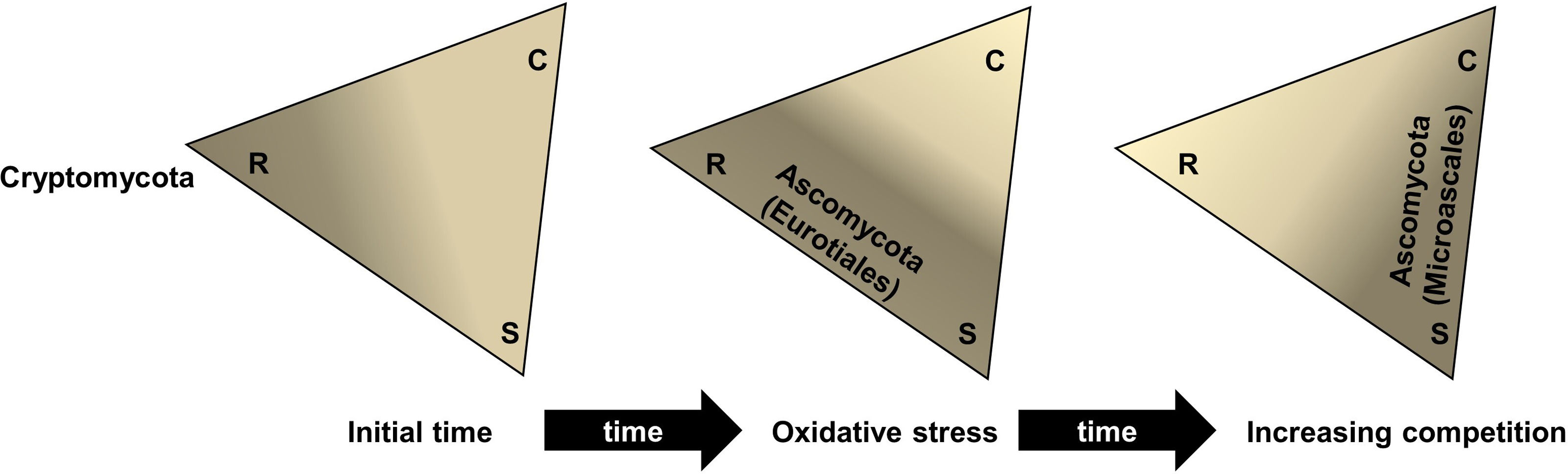

According to Boddy and Hiscox9, there are several ecological strategies that fungi may show following the Grime's C-S-R system16, and, thus, to explain the changes in fungal community exposed to different remediation events. Analyzing our data, the great dominance of the phylum Ascomycota almost entirely represented by the order Eurotiales (92.6% in APT at T0) would be indicative of a rapid response to oxidative stress of this taxon, displacing Cryptomycota members (57.3% in UT at the initial time). Schmidt-Heydt et al.35 reported the ability of Penicillium verrucosum to produce mycotoxins to face oxidative stress caused by high levels of NaCl, Cu2+ or light exposure, enabling this species to adapt to a wide variety of environments and to limit the change of other fungi. Additionally, the activation of sporulation in response to stress caused during pasteurization treatments was described in four species of fungi belonging to the order Eurotiales15. Since most Cryptomycota species are biotrophic with holocarpic and polycarpic vegetative bodies, differentiating into mono- or polysporangiate forms, and the rest of the dominant fungi are eucarpic, Cryptomycota are considered R-strategists17, while Eurotiales can be both R− and S−strategists as their reproductive and vegetative structures coexist23. These features may support the hypothesis that after the oxidation of the oily sludge, R-strategists representing Eurotiales sporulated rapidly, ensuring their detection and/or survival at the expense of easily assimilated water-soluble compounds.

In this scenario, the generation of by-products from the PSA treatment could have triggered competitive mechanisms, such as the production of dissolved or volatile organic compounds; allowing the transition from an R-strategy to a combative strategy (C-strategy) led to the existence of intermediate strategies to tolerate the remaining oxidative stress, as observed in Scedosporium sp. (Fig. 3).

S. boydii (order Microascales) has been associated with polluted environments, showing aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbon degrading capabilities31,49. However, additional research is needed to confirm the combative strategy of this fungus, the effect of treatments on changes in the mycobiota, and other variations in the dominance of fungal ecological groups may depend on the incubation time. In this regard, Sordariales members, represented by H. fuscoatra, also increased up to 60 days in ATP treatments, a fungus that was reported as dominant in other studies related to cellulose biodegradation in a forest and also in compost and vermicompost processes5.

ConclusionBased on the results obtained, it is concluded that inputs of easily assimilable organic matter in oily sludge such as wheat straw might generate changes and replacement of fungal taxa, affecting microbial colonization and consequently, possibly activating pollutant removal. Therefore, it is ecologically important to understand and compare the dynamics of the native fungal community in an oily sludge to predict the potential effects of oxidative stress and/or wheat straw amendment. This would have a significant effect on the structure and activity of the tolerant mycobiota, ultimately affecting ecological services at their original sources.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

N.A. Di Clemente was doctoral fellow of CONICET. The authors would like to thank CINDEFI, Laboratory UPL and INFIVE for the provision of their facilities with access to the equipment, material and infrastructure required to develop the present work. This work was funded by the project PICT2016-0947 (Title: “Remediation of wastes with high hydrocarbon content”, Responsible investigator: Dr. María Teresa Del Panno). Also this research was partially financed by the National Agency for Scientific and Technological Promotion (ANPCyT) of the Ministry of Science, Technology and Productive Innovation of Argentina through the PICT 2019-00207 project (Mario Carlos Nazareno Saparrat), PICT 2021 Aplicados CAT II 00036, CONICET (PIP 11220200100527CO), the Secretary of Science and Technology of the National University of La Plata, Argentina, through the R&D Project A344 (Mario Carlos Nazareno Saparrat).