The aim of this study was to identify the clinical and demographic characteristics of patients with a confirmed diagnosis of spondylodiscitis through microbiological cultures. A descriptive, observational, and retrospective study was conducted. Patients were included based on clinical and radiological evidence of vertebral infection, unspecified discitis, and/or positive microbiological cultures consistent with spondylodiscitis. For the comparison between men and women, the Student's t-test and odds ratio were employed. The Chi-square test was used to examine correlations between affected spinal levels, isolated microorganisms, and associated comorbidities. A total of 86 cases of discitis were identified, 65% of which involved male patients. The mean age was 59.0±11.5 years (range: 38–83), and the average body mass index (BMI) was 28±4.05kg/m2. Primary discitis predominated in 68% of cases, mainly at the thoracic level. Seventeen patients presented with spondylodiscitis not associated with chronic degenerative diseases. The most frequently isolated microorganisms were Staphylococcus aureus (28 cases) and Escherichia coli (21 cases). In 16 cases, intracellular pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Brucella spp. were identified, leading to an average hospital stay of 30 days. Spondylodiscitis is a serious complication, and this study highlights differences from previously published data, particularly in terms of the microorganisms involved and the demographic profile of the population.

El objetivo de este estudio fue identificar las características clínicas y demográficas de los pacientes con diagnóstico confirmado de espondilodiscitis por cultivo microbiológico. Se realizó un estudio descriptivo, observacional y retrospectivo. Se incluyeron pacientes con evidencia clínica y radiológica de infección vertebral, discitis no especificada o cultivos microbiológicos positivos compatibles con espondilodiscitis. Para la comparación entre varones y mujeres, se empleó la prueba t de Student y la odds ratio. Se utilizó la prueba de chi cuadrado para examinar correlaciones entre niveles espinales afectados, microorganismos aislados y comorbilidades asociadas. Se identificaron 86 casos de discitis, el 65% en varones. La media de la edad de los afectados fue de 59±11,5 años (rango: 38-83 años) y el índice de masa corporal promedio fue de 28±4,05kg/m2. La discitis primaria predominó en el 68% de los casos, principalmente en la zona torácica. Diecisiete pacientes presentaron espondilodiscitis sin asociación con enfermedades degenerativas crónicas. Los microorganismos más frecuentemente aislados fueron Staphylococcus aureus (28 casos) y Escherichia coli (21 casos). En 16 casos se identificaron patógenos intracelulares como Mycobacterium tuberculosis y Brucella spp., lo que provocó una estancia hospitalaria media de 30 días. La espondilodiscitis es una complicación grave y este estudio destaca las diferencias con los datos publicados anteriormente, en particular, en cuanto a los microorganismos implicados y el perfil demográfico de la población.

Spondylodiscitis is a complex disease, whose diagnosis and management remain challenging. It has an estimated incidence of 0.4 to 2 individuals per 100000 inhabitants per year8,22,41. It primarily affects adults, with a male-to-female ratio of 1.5 to 3:13,10,16,33. The term spondylodiscitis is commonly used for the infectious disease of the intervertebral disc and the epiphyseal plate8,19,27, but there are numerous conditions that can mimic the presence of an infectious vertebral disease (e.g. synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteomyelitis syndrome)38,50. For this reason, it can be divided into two categories: sterile or inflammatory spondylodiscitis (aseptic) and pyogenic or bacterial spondylodiscitis14. Pyogenic spondylodiscitis can be classified as a primary or secondary infection, depending on whether the patient has had previous spinal surgery or not14. The identification of a causative pathogen is essential to guide the treatment process14. The microbiological spectrum is very broad, it can be classified etiologically as pyogenic, granulomatous (tuberculosis, brucellosis, fungal) and parasitic7,19. Pyogenic infections produced by Staphylococcus aureus make up 67% of the cases8,33,43. Aseptic spondylodiscitis is less common and is related to systemic inflammatory diseases50. Both are rare severe conditions and are potentially fatal with an annual mortality rate of 11%13,19,30,41. However, in recent years, there has been a steady increase in cases, perhaps due to the elevated life expectancy of patients suffering from chronic diseases (e.g. diabetes, cancer, cirrhosis, chronic renal failure and, human immunodeficiency virus infection)13,26,30,41.

In Mexico, there is currently scant data on the epidemiology of spondylodiscitis. For this reason, the aim of this study was to identify the clinical and demographic characteristics of patients with suspected and/or definitive diagnosis of spondylodiscitis in a neurosurgery department.

Materials and methodsStudy design and ethicsA descriptive, observational, retrospective study was conducted from January 2002 to January 2022 in the Department of Neurosurgery at the South-Central Highly Specialized Hospital (SCHSH)31. The SCHSH is a reference institution for tertiary care of the population located in Mexico City. It often receives patients from all over the country and is responsible for providing health services to 1% of the Mexican population12,17,18,21. According to the STROBE47 recommendations, the electronic data from the clinical records of patients diagnosed with spondylodiscitis were analyzed.

This research adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The institutional review board approved this study, granting a waiver for informed consent.

Patient selectionConvenience sampling of patients was conducted using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10)28 M46.2 Osteomyelitis of vertebra, M46.3 Infection of intervertebral disc (pyogenic), M46.4 Discitis, unspecified, M46.5 Other infective spondylopathies, M49.0 Spondylopathies in diseases classified elsewhere, M49.1 Brucellosis spondylitis, M49.2 Enterobacterial spondylitis, M49.3 Spondylopathy in other infectious and parasitic diseases classified elsewhere.

Selection criteriaAge between 18 and 85 years with clinical symptoms and signs such as: back pain, fever, weight loss, fatigue, weakness and/or sensory deficits in the limbs, associated to radiological data of vertebral infection and unspecified discitis in MRI or CT (presence of destructive lesions in two or more adjacent vertebrae and in the intervertebral disc, spondylodiscitis as reported by a specialist radiologist and/or positive microbiological culture compatible with spondylodiscitis). Exclusion criteria were patients who had incomplete clinical records, treatment, or follow-up notes. Patients with confirmation of an alternative diagnosis to account for the clinical and radiological features (e.g. myeloma) were also excluded.

Data collectionDemographic data, such as sex, age, predominant symptoms and/or clinical debut, microorganisms found in the microbiological culture and most common comorbidities, were obtained. Risk factors (diabetes, hypertension, renal disease) were considered present if the electronic medical record showed that the patient was diagnosed with these conditions, as recorded by a physician. We did not specifically evaluate laboratory data to confirm/refute these diagnoses or grade the severity of the diagnoses. Patients were monitored daily during the hospital stay and in an outpatient program every fifteen days. The results for the outcome were evaluated based on days of hospitalization, sequelae and number of days unfit for work among active workers.

Data collection was done manually and daily through the electronic clinical file by a first investigator (M.A.D.E.) using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10)28 codes. In the case of missing data, the electronic system for radiological studies was reviewed (M.F.G.R.).

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics were used to obtain frequencies, measures of central tendency (median or mean) and measures of dispersion (proportions or standard deviation). For the comparison of the groups between men and women, the Student's t test was used along with the odds ratio, depending on the case.

To compare the groups between men and women, both the Student's t-test and the odds ratio were applied. The Chi-square test was utilized to assess correlations between affected vertebral levels, isolated microorganisms, and associated comorbidities.

All results were considered statistically significant when the p value was ≤0.05. The database was structured by a second investigator (J.C.L.V.) using the Microsoft Excel™ program, the statistical analysis was conducted by a third investigator (D.A.V.M.) using the IBM SPSS V 21™ program.

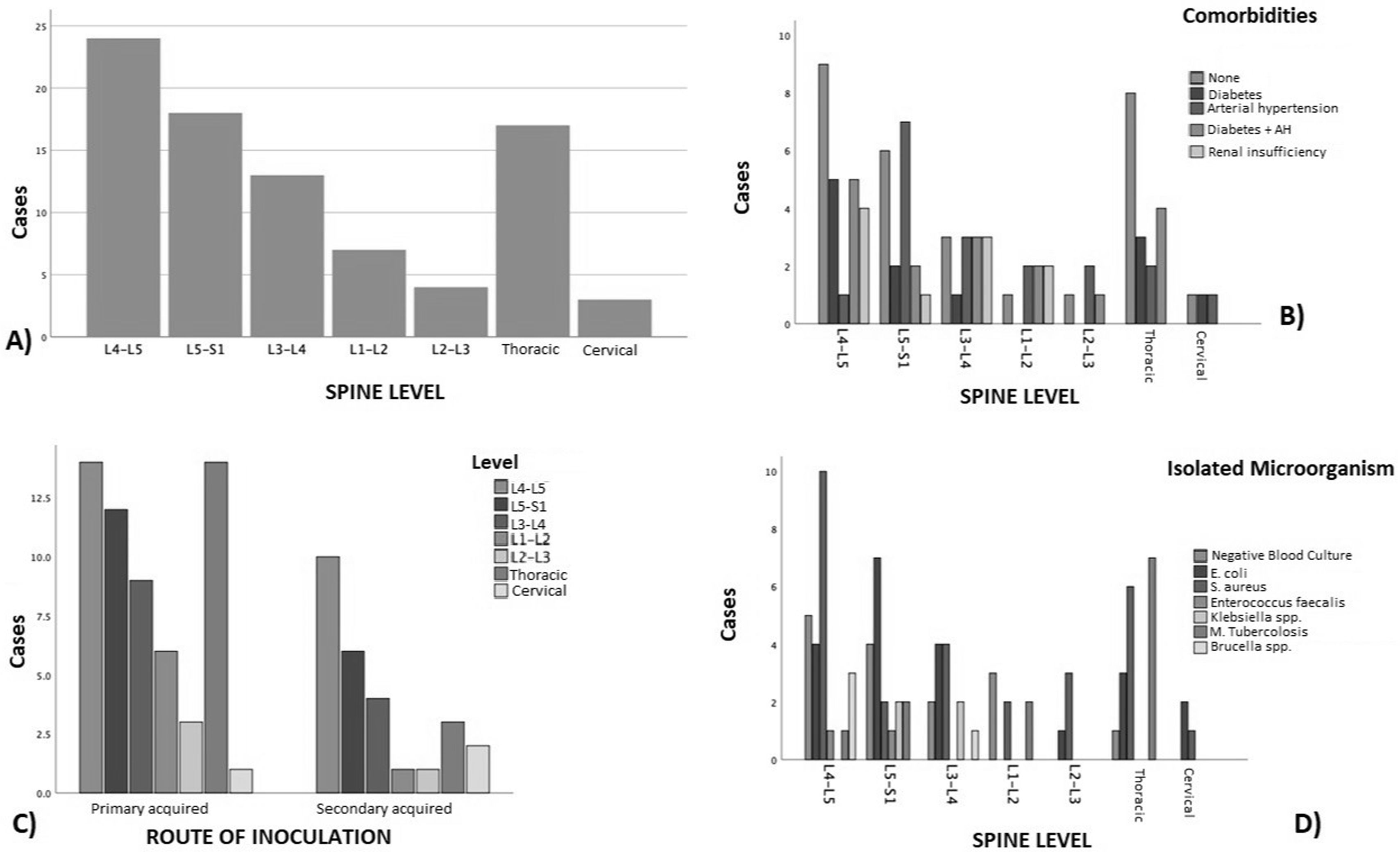

ResultsOver a 120-month period, 152 consecutive patients were diagnosed with ICD-1028: M46.2/M46.3/M46.4/M46.5/M49.0/M49.1/M49.2/M49.3. After a thorough screening, 86 patients were included; 47 cases were excluded because they had received treatment outside of the institution or had an incomplete antibiotic course of treatment. Moreover, 19 patients had no follow-up notes or radiological files were not available (Fig. 1). The study showed a male predominance (65%) with a male-to-female ratio of 2:1. The average age was 59.0±11.5 years (range 38–83), and the average body mass index (BMI) by Quetelet formula15 was 28±4.05kg/m2. Most cases were primary discitis (68%), most of which occurred at the thoracic level. However, when analyzing the most affected site globally, the lumbar levels (n=66 cases), especially the L4-L5 level (27.9%), were the most involved, followed by the thoracic level (n=17 cases) (Fig. 2 and Table 1). The most common microorganisms were S. aureus (28 cases), and Escherichia coli (21 cases). In sixteen cases, intracellular microorganisms considered difficult to treat (Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Brucella spp.) were found (Tables 2 and 3). The average hospital stay was 30 days. In fifteen cases, the causal microorganism was not identified.

(A) Distribution of patients by affected spinal level. (B) Distribution of cases by level of injury associated with comorbidities; we can observe that hypertension was the comorbidity most strongly associated, both as the sole associated disease or in combination with diabetes mellitus. (C) Types of discitis in relation to etiology; at all spinal levels there was a preponderance for the primary origin. (D) Affected levels, based on the etiological microorganism, mostly showed growth of S. aureus.

Demographic characteristics.

| Variables | N=86 | Menn=58 | Womenn=28 | Statistical analysis | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 59±11.15 | 58±10.7 | 60±12 | t=0.7806 | 0.4373 |

| Weight (kg) | 76±12.03 | 78±12 | 72±10.6 | t=2.2538 | 0.0268* |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28±4.05 | 28±3.99 | 27±4.2 | t=1.0707 | 0.2874 |

| MLD (days) | 30±18.26 | 31±17.6 | 28±19.6 | t=0.7137 | 0.4774 |

| Types of discitis | |||||

| Primary | 59 (69%) | 42 (48.8%) | 18 (20.9%) | OR=1.4583 | 0.4430 |

| Secondary | 27 (31%) | 17 (19.76%) | 10 (11.62%) | OR=0.7846 | 0.6205 |

| Localization | |||||

| L1-L2 | 7 (8.1%) | 5 (5.8%) | 2 (2.3%) | OR=1.2264 | 0.8146 |

| L2-L3 | 4 (4.65%) | 2 (2.32%) | 2 (2.32%) | OR=0.4643 | 0.4554 |

| L3-L4 | 13 (15.1% | 9 (10.45%) | 4 (4.65%) | OR=1.1020 | 0.8813 |

| L4-L5 | 24 (27.9%) | 15 (17.45%) | 9 (10.45%) | OR=0.7364 | 0.5436 |

| L5-S1 | 18 (20.9%) | 14 (16.25%) | 4 (4.65%) | OR=1.9091 | 0.2979 |

| Thoracic | 17 (19.7%) | 11 (12.8%) | 6 (6.9%) | OR=0.8582 | 0.7882 |

| Cervical | 3 (3.48%) | 2 (2.32%) | 1 (1.16%) | OR=0.8929 | 0.9277 |

| Etiology | |||||

| E. coli | 21 (21.4%) | 12 (13.95%) | 9 (10.45%) | OR=0.5507 | 0.2499 |

| S. aureus | 28 (32.55%) | 20 (23.25%) | 8 (9.30%) | OR=1.3158 | 0.5841 |

| E. faecalis | 2 (2.32%) | 2 (2.32%) | 0 | OR=2.5221 | 0.5547 |

| Klebsiella spp. | 4 (4.65%) | 3 (3.5%) | 1 (1.15%) | OR=1.4727 | 0.7425 |

| M. tuberculosis | 12 (13.95%) | 8 (9.30%) | 4 (4.65%) | OR=0.9600 | 0.9507 |

| Brucella spp. | 4 (4.65%) | 1 (1.15%) | 3 (3.5%) | OR=0.1462 | 0.1030 |

| Negative cultures (aseptic spondylodiscitis) | 15 (17.45%) | 12 (13.95) | 3 (3.5%) | OR=2.1739 | 0.2616 |

| Working status | |||||

| Worker | n=43 (50%) | 37 (43%) | 6 (7%) | OR=6.4603 | 0.0005* |

| Leave (days) | 222±98 | 215±105 | 266±64 | t=0.9987 | 0.3238 |

Correlation between affected spinal level and isolated microorganism through culture.

| Variable | E. coli (n) | Test χ2 | p value | S. aureus (n) | Test χ2 | p value | E. faecalis (n) | Test χ2 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1-L2 (N=7) | 1 | 0.511 | 0.474 | 1 | 1.288 | 0.256 | 0 | 0.275 | 0.275 |

| L2-L3 (N=4) | 2 | 0.58 | 0.446 | 2 | 1.64 | 0.200 | 0 | 0.192 | 0.661 |

| L3-L4 (N=17) | 5 | 0.163 | 0.686 | 7 | 0.527 | 0.467 | 0 | 0.766 | 0.381 |

| L4-L5 (N=24) | 4 | 1.390 | 0.238 | 9 | 0.213 | 0.644 | 2 | 2.321 | 0.127 |

| L5-S1 (N=20) | 8 | 2.846 | 0.091 | 4 | 2.195 | 0.138 | 1 | 0.1777 | 0.673 |

| Thoracic (N=17) | 3 | 0.701 | 0.402 | 6 | 0.023 | 0.879 | 0 | 0.766 | 0.381 |

| Cervical (N=3) | 2 | 2.756 | 0.096 | 1 | 0.000 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.112 | 0.737 |

| Variable | Klebsiella spp. (n) | Test χ2 | p value | M. tuberculosis (n) | Test χ2 | p value | Brucella spp. (n) | Test χ2 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1-L2 (N=7) | 0 | 0.181 | 0.670 | 2 | 1.356 | 0.244 | 0 | 0.275 | 0.599 |

| L2-L3 (N=5) | 0 | 0.125 | 0.723 | 0 | 0.861 | 0.353 | 0 | 0.192 | 0.661 |

| L3-L4 (N=17) | 2 | 8.311 | 0.003* | 0 | 3.436 | 0.063 | 0 | 0.766 | 0.381 |

| L4-L5 (N=24) | 0 | 0.793 | 0.373 | 1 | 2.656 | 0.103 | 3 | 8.030 | 0.004* |

| L5-S1 (N=20) | 0 | 0.620 | 0.431 | 2 | 0.339 | 0.560 | 0 | 0.942 | 0.331 |

| Thoracic (N=17) | 0 | 0.504 | 0.477 | 7 | 13.078 | 0.0003* | 0 | 0.766 | 0.381 |

| Cervical (N=3) | 0 | 0.074 | 0.785 | 0 | 0.504 | 0.477 | 0 | 0.112 | 0.737 |

Correlation between isolated microorganism through culture and associated comorbidities.

| Variable | DM2 (n) | Test χ2 | p value | SAH (n) | Test χ2 | p value | CKD (n) | Test χ2 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | 12 | 1.286 | 0.256 | 14 | 3.019 | 0.082 | 3 | 0.116 | 0.733 |

| S. aureus | 16 | 2.141 | 0.143 | 13 | 0.142 | 0.706 | 2 | 0.953 | 0.328 |

| E. faecalis | 1 | 0.148 | 0.700 | 2 | 0.449 | 0.502 | 0 | 0.409 | 0.522 |

| Klebsiella spp. | 1 | 0.028 | 0.867 | 2 | 2.247 | 0.133 | 0 | 0.269 | 0.604 |

| M. tuberculosis | 1 | 7.269 | 0.007* | 2 | 5.375 | 0.020* | 0 | 1.835 | 0.175 |

| Brucella spp. | 1 | 0.148 | 0.700 | 1 | 0.256 | 0.612 | 1 | 1.425 | 0.232 |

| Negative cultures (aseptic spondylodiscitis) | 6 | 0.129 | 0.719 | 7 | 0.007 | 0.933 | 4 | 3.999 | 0.045* |

| Variable | No. comorbidities (n) | Test χ2 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | 4 | 2.396 | 0.121 |

| S. aureus | 7 | 1.070 | 0.300 |

| E faecalis | 1 | 0.005 | 0.943 |

| Klebsiella spp. | 0 | 0.937 | 0.333 |

| M. tuberculosis | 9 | 12.311 | 0.0004* |

| Brucella spp. | 2 | 1.795 | 0.180 |

| Negative cultures | 4 | 0.189 | 0.663 |

The most common comorbidities associated with spondylodiscitis were diabetes mellitus and hypertension, either alone or in combination, across all the levels studied (Table 3). However, it should be mentioned that there were 17 patients who presented with spondylodiscitis not associated with any chronic degenerative disease. The debut symptom in most of the cases where a microorganism was isolated was femoral weakness of a specific limb and/or the presence of associated radiculopathy. A greater (denser) motor deficit was observed in the case of an infection by intracellular microorganisms (Figs. 2 and 3). The remaining results are shown in Table 1. Surgical management was preferred in 44 patients, mostly by posterior approach (90.1%), and 17 cases required a second procedure? for spinal fixation. Nonetheless, all cases received antibiotic treatment depending on the isolated microorganism.

An active working population of 43 patients was obtained. They had an average medical leave day of 222±98 (SD). Meanwhile, the days of hospital stay were 30±18.26 SD (range 3–75 days). Active worker patients reported low back pain and weakness as the main complication after the end of treatment. There were fourteen patients who experience complications for more than 300 days, which led to the cessation of their activities as workers. Only two of these cases were associated with complex intracellular microorganisms. In addition, when analyzing the values obtained for patients with hospital stay and medical leave, a correlation index was shown for both with an R2 of 0.008 and 0.0153 respectively. On the other hand, when analyzing the collective labor agreement32, it is possible to infer a labor cost for the company (calculated at level 8, worker category) of an approximate amount ranging between 4846.22 and 7972.36 dollars for disability per worker, without considering the cost of the hospital stay or medical care (15367.95 dollars per 30 days, approximately)39.

In all cases, the antibiotic selected for treatment was based on the microorganism identified from the microbiological culture; in most cases a prescription for third generation cephalosporin, as well as glycopeptides, was indicated (Fig. 3).

(A) Distribution of use of antibiotics. (B) Distribution of complications in working patients. (C) Number of cases based on the isolated pathogenic microorganism and most common comorbidities. It was found that in both Gram positive and Gram negative cases, renal failure was a common denominator. On the other hand, most of the patients who presented with M. tuberculosis had no associated comorbidities. (D) The complications associated with microorganisms can be observed, all of them resulting in crural pain of different intensities.

This study enabled the comparison of clinical data including the topographic location of infection, microorganism involvement, patient age, sex, and treatments, among other factors.

Similar to Álvarez-Narváez et al.1 (Mexico), the age in our results was lower than that documented by different studies with similar characteristics, such as the cases of Schoof et al.42 (Germany), Heuer et al.20 (Germany), Pola et al.34 (Italy), Thavarajasingam et al.48 (United Kingdom) and Cardoso et al.6 (Portugal), who mention an average age of 64.6±14.8, 66 (range 19–89), 64.98±0.97, 63.5 and 65.3 (range 25–86) years respectively. This data is five years higher than the average age obtained in this study (59.0 years), only being surpassed by Nóbrega-Danda et al.11 (50.94±15.84 years) in Brazil and Bustos-Mora et al.4 (47.7±2.48 years) in Mexico (Guadalajara, Jalisco). The distribution by sex in all the studies, including ours, shows a predominance of males, always above 60%. The BMI obtained in this study (28±4.05kg/m2) was almost the same as that reported by Krishnan et al.24 (28.3±3.19 with a range of 21.6–33.9kg/m2).

Polanco-Armenta et al.35 found spondylodiscitis to be the third cause of spinal pathology in our country. Most of the patients are adults of working age which generates prolonged periods of medical leave, extended hospital stays, and a great amount of time invested in the care of these diseases, all of which have high economic, institutional, and social repercussions10,22,41.

The most affected site of spinal infection was the lumbar region, followed by the thoracic region, which is consistent with the findings in other studies.

According to Stangenberg et al.45,46, there is no relationship between pre-existing comorbidities and the site of pyogenic spondylodiscitis, except for previously documented bacterial endocarditis. In our study, arterial hypertension, either alone or in combination with diabetes mellitus, was present in nearly all cases, irrespective of the localization of the infection. On the other hand, renal failure occurred in 11.67% of the cases, all of which had lumbar localization (L1-L5). It should be mentioned that, in this group of patients, recurrent urinary tract infections may have been present, leading to embolisms through the venous plexus of Batson, which in turn communicates with the venous return of the spine2,5,29,37.

Data obtained by Sans et al.40, reviewing the French hospital discharge database (PMSI) reported S. aureus (15%) and Mycobacteria (21%) as the main causative agents, which is similar to our obtained results (28% and 13.95%, respectively). However, they reported a frequency of 34% for cases in which it was not possible to isolate a specific pathogenic microorganism, while in our study, only 17.45% of patients did not show bacterial development in the cultures. Another significant fact was that 4.65% was obtained for the isolation of Brucella spp., which was ten times higher than the rate reported by Sans et al.40 Notwithstanding, it should be noted that this was significantly lower than the rate described by Lebre et al.25 in Portugal (54 cases in 25 years).

Karadimas et al.23 (Denmark) reported a frequency of 33% for S. aureus, 13% for Mycobacterium and 41% for unidentified agents, which differ from our results (except for mycobacteria). Similarly, to Pola et al.34 (Italy), other pathogenic microorganisms such as E. coli and Klebsiella were found in our study. In the present study, E. coli was the second most prevalent microorganism (21.4%), although its frequency was still lower than that reported by Álvarez-Narváez et al.1 (35.3%).

With regard to infections by Mycobacterium, given our results and those obtained by Finger et al.14, we can infer that the decrease in infections by these microorganisms is on the rise given the fact that they were previously considered the main cause of infection and today pyogenic spondylodiscitis is more predominant. Furthermore, unlike Shetty et al.44, who mention that the older the patient the greater the risk of infection by acid-resistant microorganisms, in our study middle-aged adults did not exhibit this elevated risk.

As observed by Finger et al.14, in Latin America (Brazil), the origin of the disease was primary in most cases, perhaps given the similarities between the sociodemographic characteristics of both populations. This is of great importance because, according to Tschugg et al.49, mortality is significantly higher in patients with primary spondylodiscitis. There were no mortality rates in our study, and no drug consumption was reported.

The hospital stay observed by Finger et al.14 (34.6+25.9) and Prost et al.36 (33.63+1.78) days is consistent with that obtained by us (30±18.26 SD). Finger et al.14 (46.9+19.3 days) and Chong et al.9 (between 25 and 51 days) reported a longer hospital stay for those cases with pyogenic microorganisms, such as S. aureus.

The results obtained must be analyzed with caution because they represent an isolated sector of the Mexican health system that corresponds only to a specific population. The retrospective nature of the study limits the ability to establish causality. The data collected relies on existing medical records, which may lack detail or contain inaccuracies. Although common comorbidities, such as diabetes and hypertension were recorded, other potential confounding factors, such as lifestyle habits (e.g., smoking, alcohol consumption) were not systematically assessed, which may influence the results.

A key strength of the study is the use of an electronic medical record (EMR) system, which the institution mandates to securely store both labor and medical information for all workers. This systematic use of EMRs ensures that data collection is thorough, reliable, and standardized, minimizing the risk of missing or incomplete data. The ability to track longitudinal health information allowed for more accurate identification of clinical patterns and comorbidities over time, enhancing the overall robustness of the dataset.

Additionally, the EMR system enabled efficient access to a large volume of patient data, facilitating the retrospective design of the study. This contributed to the comprehensive follow-up of each case, allowing the study to capture critical details, such as treatment outcomes, length of hospital stay, and return-to-work timelines, which are often challenging to document in non-digital systems.

Another strength lies in the high level of detail recorded for each patient, including demographic, clinical, and microbiological data, which enabled precise correlations between infection types, comorbidities, and outcomes. This wealth of data strengthens the ability of the study to draw meaningful conclusions about the characteristics of spondylodiscitis in this specific population, contributing valuable insight to the literature on spinal infections.

ConclusionsThe average age in our study was lower than that reported in studies with similar characteristics. The distribution by sex in all the studies, including ours, shows a predominance of males, always above 60%. The BMI obtained in this study (28±4.05kg/m2) was almost the same reported by other studies.

Spondylodiscitis is a severe complication that entails serious sequelae in working and non-working patients. In the present study, a difference was observed compared to previous publications in the medical literature, not only in relation to the microorganisms found but also regarding the general demography of the population studied. Additionally, a high morbidity was found, leading to the termination of work activities for some patients.

CRediT authorship contribution statementMADE, DAVM, MFGD and RSM: conceptualization, writing initial draft and database creation. JCLV and LMO: data collection, statistics analysis, editing, translation and supervision. MECM and EACR: data collection and second editing. AJMS and UGG: supervision and final editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

FundingThis report did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.