The spontaneous coffee fermentation process can be regulated through the application of microbial starter cultures, which are used to enhance the quality of the coffee. In this study, microorganisms derived from coffee fermentations conducted on a representative farm in Southwestern Colombia, where specialty export-type coffee is produced, were isolated, characterized, and identified. The methodology used was based on cultivation techniques of key microbial groups in coffee fermentation, which enabled to establish a collection of microorganisms with future applications in postharvest coffee processing. The microorganisms that exhibited significant characteristics within the established criteria of this study, which were used for the selection of starter cultures for coffee fermentation, belonged to microbial genera or species that are commonly found during the coffee fermentation process. Consequently, the strains Acetobacter tropicalis m108, Kosakonia cowanii P121, Leuconostoc mesenteroides M154, L. mesenteroides M159, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum M157, Pichia kluyveri Y144, P. kudriavzevii Y150, Wickerhamomyces anomalus Y149, and Rhodotorula mucilaginosa Y147 were selected for further study. These strains represent a valuable genetic resource that could contribute to enhancing the quality of coffee from the region, particularly in regard to its cup quality, for future use as starter cultures.

El proceso de fermentación espontánea del café se puede regular mediante la aplicación de cultivos iniciadores microbianos, que se utilizan para mejorar la calidad del café. En este estudio se aislaron, caracterizaron e identificaron microorganismos derivados de fermentaciones de café realizadas en una finca representativa del suroccidente colombiano, donde se produce café especial tipo exportación. La metodología se basó en técnicas de cultivo de grupos microbianos claves en la fermentación del café, lo que permitió establecer un banco de microorganismos con aplicaciones futuras en el procesamiento poscosecha del café. Los microorganismos que presentaron características significativas dentro de los criterios establecidos en este estudio, que se utilizaron para la selección de cultivos iniciadores para la fermentación del café, pertenecieron a géneros o especies microbianas que se encuentran comúnmente durante el proceso de fermentación del café. En consecuencia, las cepas Acetobacter tropicalis m108, Kosakonia cowanii P121, Leuconostoc mesenteroides M154, L. mesenteroides M159, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum M157, Pichia kluyveri Y144, P. kudriavzevii Y150, Wickerhamomyces anomalus Y149 y Rhodotorula mucilaginosa Y147 fueron seleccionadas para estudiarlas con más detalle. Estas cepas representan un valioso recurso genético que podría contribuir a mejorar la calidad del café de la región, en particular en lo que respecta a su calidad en taza mediante su uso futuro como cultivos iniciadores.

The global recognition of Colombian coffee among consumers has enabled the country to sustain the livelihoods of approximately 540000 families through coffee exports (“Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia, FNC, institutional website”, 2025). The Superintendency of Industry and Commerce (SIC) has granted the designation of origin to Colombian coffee since 200536. However, the geographical and climatic characteristics, as well as the traditional craft techniques applied to the cultivation and postharvest processing of coffee in each department of the country, result in coffees with different levels of quality. Consequently, the following coffees have been granted regional designation of origin in Colombia over the years: Nariño and Cauca in 2011; Huila in 2013; Santander in 2014; and Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta and Tolima in 2017 (“FNC Institutional Page,” 2025). Café de Nariño is a washed Arabica coffee that is renowned for its distinctive high acidity, medium body, sweet flavor notes, and clean, smooth, and very pronounced aroma35. It has gained significant recognition in the international market6.

The sensory quality of coffee depends on a complex interplay of natural and cultural factors that are unique to each coffee-growing region. Nevertheless, there is considerable interest in coffee fermentation, as it has been shown that the microbial metabolites produced during the coffee fermentation process can migrate to the coffee seeds, thus influencing the flavor and aroma of coffee17. Consequently, the coffee fermentation process is a way of developing new sensory profiles and improving the final cupping score, with the goal of getting a better value for the final product18. However, the coffee fermentation process is spontaneous and is driven by microbial communities that vary according to the intrinsic and extrinsic factors surrounding the process50. Accordingly, in order to ensure consistency and controllability of the fermentation process, the use of starter cultures represents a viable strategy26. The targeted introduction of starter cultures to raw materials facilitates the management of the overall fermentation process, thereby mitigating the risk of fermentation failure while enhancing safety, stability, and the sensorial value of the end products10.

In this context, only a limited number of studies have been conducted on the use of starter cultures for coffee fermentation22. It should be noted that the use of starter cultures in a controlled process of coffee mucilage removal has been shown to enhance the production of a diverse range of volatile compounds11. Among the microorganisms employed, yeasts are the most commonly used as starter cultures. A number of different strains of the species Candida parapsilosis, Meyerozyma caribbica, Pichia fermentans, P. guilliermondii, P. kluyveri, Torulaspora delbrueckii, Saccharomyces sp., S. cerevisiae, Wickerhamomyces anomalus and Yarrowia lipolytica, have been identified as having particular utility as starter cultures13,17,42. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) have also been utilized as starter cultures, including the following strains. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum (basonym: Lactobacillus plantarum) LPBR017,12, L. plantarum MTCC542243, L. plantarum CCMA 10653,4, Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus HN00147, Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris ATTCC 1925746, and Leuconostoc mesenteroides CCMA11053,4. Furthermore, additional bacterial strains, including Bacillus sphaericus MTCC 754343, Arthrobacter koreensis, B. subtilis and Pantoea dispersa30, have been employed as starter cultures. In Colombia, bacterial and yeast species belonging to the genera Lactiplantibacillus, Pichia, and Torulaspora have been identified32.

Despite the considerable expansion of the market for microbial starter cultures in coffee processing, the range of available strains remains comparatively limited in comparison with other fermented beverage industries13. It is therefore necessary to uncover novel microbial strains, which will lead to new perspectives on coffee quality9,13. Furthermore, there are relatively few studies in Colombia that are specifically focused on characterizing this type of starter culture. In order to identify microbial strains that exhibit functional properties devoid of negative traits, a series of tests must be conducted. These include tolerance to stressful fermentation conditions, identification of key metabolite producers, and an evaluation of relevant technological parameters10. Furthermore, it is essential to recognize that the predominant microorganisms in coffee fermentation depend on the specific fermentation process employed. Therefore, it is recommended to isolate, through natural selection, the strains that best adapt to these stressful environments10. The purpose of this research was to isolate bacteria and yeasts that are predominant during the solid-state fermentation of Colombian coffee and to characterize some of their functional properties, with a view to identifying strains that could be used as starter cultures.

Materials and methodsCoffee postharvest processing and samplingThe Coffea arabica cherries were harvested from July to September 2021 and 2022, during the coffee harvest season at the Loma Gorda farm in Buesaco, Nariño, Colombia. This farm was chosen for their expertise in producing specialty coffees. Three processing trials were conducted annually. In the year 2021, the initial trial commenced on August 11 (08/11), the second on August 13 (08/13), and the third on 15 September 15 (09/15). In the year 2022, the processes initiated on July 21 (07/21), July 30 (07/30) and August 19 (08/19). Coffee processing was conducted following a protocol based on traditional practices, where only healthy and mature coffee cherries were handpicked. Ripe cherries were immersed in water-filled tanks for sorting. The cherries were subjected to a prefermentation process in woven polypropylene bags for a period of 24–72h. Subsequently, they were combined with fresh cherries in a single batch, at a ratio of 7:3. The hand-selected cherries were mechanically depulped (Jotagallo No. 23\4 Marsella, Pereira, Colombia). The depulped beans were then sorted using a rotary drum sieve (10mm×30mm holes) and allowed to spontaneously ferment under solid-state fermentation (without the addition of water) in a cement tank (1.70m×1.30m×0.70m). The depulped beans underwent fermentation for approximately 10h. The coffee grower determines the duration of fermentation by feeling the friction between the coffee beans in their hands, which indicates the removal of the mucilage layer adhering to the beans. The fermented beans were manually washed with clean water and then dried in a solar tunnel dryer until the moisture was reduced to 10–12%. The samples were obtained during the course of the processes conducted in 2021. Twenty units of fresh cherries (FC) and 20 units of prefermented cherries (PC) were randomly selected from the batches prepared for processing on the designated day. Additionally, 10g of fermenting coffee beans were collected from different points of the fermentation mass: the surface, middle, and bottom of the tank, and combined in a single 30g sample to represent the entire tank to each sample16. The samples were collected at varying time points throughout the fermentation process. The initiation of the fermentation process in depulped coffee was demarcated at zero time (0h). All samples were collected in triplicate, placed aseptically in sterile plastic bags, and immediately transported to the laboratory in iceboxes for microbiological analyses.

Measurement of environmental and physicochemical parametersThe environmental temperature (ET, °C) and the relative humidity (RH, %) were continuously monitored using sensors (AM2301 sensor/module; Aosong Electronics Co., Ltd. Guangzhou, China) placed in the fermentation room. The pH and Brix degrees (°Bx) of the fermentation mass were measured using calibrated instruments, including a portable pen-type pH meter (Model 8681; AZ Instrument Corp., Taiwan, China), and a refractometer (Model RF15; Extech Instruments, Rotterdam, Netherlands). The temperature (°C) was monitored using sensors (DS18B20 digital temperature sensor; Maxim Integrated, California, USA) located at the surface (ST), middle (MT) and bottom (BT) of the fermenting mass. The data obtained from the sensors were automatically stored in a data logger system5. All measurements were conducted in quadruplicate at each sampling point throughout the fermentation processes conducted in both 2021 and 2022.

Quantification and isolation of microorganismsThe protocol described by Córdoba et al.5 was followed, as outlined below. Aliquots (10g) of the coffee cherry or fermenting coffee bean samples were mixed with 90ml of sterile peptone water (1g/l bacteriological peptone from Oxoid, Basingstoke, England) and homogenized in an Orbital Shaker at 200rpm for 20min. These aliquots were used for decimal serial dilution (0.85% w/v NaCl; PanReac AppliChem, Barcelona, Spain) and plated in duplicate. Selective agar media and specific incubation conditions were used to target five microbial groups. Aerobic mesophilic bacteria (AMB) were quantified using plate count agar (PCA; HiMedia, Pennsylvania, USA) supplemented with 0.4mg/ml nystatin (Sanfer, Bogota, Colombia) to inhibit fungal growth. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) were cultured on MRS agar (Panreac Applichem, Barcelona, Spain) supplemented with nystatin (0.4mg/ml). Yeasts and molds were cultivated on YGC medium (Condalab, Madrid, Spain). Acetic acid bacteria (AAB) were grown on modified deoxycholate-mannitol-sorbitol agar (mDMS) supplemented with nystatin (0.4mg/ml). Finally, enterobacteria were targeted using violet-red-bile-glucose agar (VRBG) (Pronadisa, Madrid, Spain). All agar plates were incubated aerobically at room temperature for 72h to detect bacterial growth and up to five days to detect fungal growth, except for MRS, which was incubated anaerobically at room temperature in an AnaeroJar 2.5 l (Oxoid, Hampshire, United Kingdom). For each agar medium and sampling time, an appropriate dilution containing 30–300 colonies was used to ensure accurate estimation. The counts (log CFU/g) were the means of duplicate analyses. The macroscopic and microscopic characteristics of the colonies in each dilution were described in detail, and the most representative colonies were purified in the respective media and culture conditions for each microbial group. The microbial isolates were preserved by subculture and freezing methods, as described by Zhang et al.50.

Evaluation of stress tolerance and desired metabolic products produced by microbial isolates derived from coffee fermentationThe screening of coffee-fermenting microorganisms was conducted by evaluating their tolerance to stress produced in the culture media where they were originally isolated18. This was done under the following conditions: different pH values (3.5, 4, 6, and 8) and incubation temperatures (room temperature, 25, 35, and 45°C), as well as different concentrations of ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) (6, 8, 10, and 12% [w/vol]) and acetic acid (Baker Mallinckrodt, Phillipsburg, USA) (1, 2, 3, and 5% [w/vol]). Additionally, the tolerance of the microorganisms to varying concentrations of glucose and fructose (Baker Mallinckrodt, Phillipsburg, USA) (5, 15, 20, 30% [w/vol]) in a basal medium containing 0.05% [w/vol] yeast extract (Panreac, Barcelona, Spain), 0.3% [w/vol] peptone (Oxoid, Basingstoke, England), and 2.5% [w/vol] agar (Condalab, Madrid, Spain) was also evaluated8. The activity of the pectin methylesterase (PME) and pectin lyase (PL) enzymes of AMB and yeasts, was evaluated in accordance with the protocol proposed by Masoud and Jespersen31. The inoculum concentration was adjusted to 1.5×108CFU/ml in accordance with the McFarland scale33. The enzymatic activity of PME and PL was expressed in enzymatic units per volume (U/ml)40,48. In order to evaluate the production of lactic acid in the LAB and of acetic acid in the AAB, inoculum sizes of 1.5×108CFU/ml were prepared according to the McFarland scale33. Subsequently, 5ml of each bacterial inoculum were inoculated in 195ml of MRS broth and mDMS broth respectively, which had been supplemented with 0.5% ethanol and the cultures were incubated at 30°C for a period of 48h19. The quantification of each acid was conducted through titration, whereby 50ml of the sample was titrated with 0.1M NaOH (Baker Mallinckrodt, Phillipsburg, USA) using phenolphthalein (Baker Mallinckrodt, Phillipsburg, USA) as the indicator19,20. The experiments were conducted in triplicate for each microbial isolate and the microorganisms.

Partial characterization of the 16S ribosomal gene (16S rDNA) and the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region in bacteria and yeast selectedDNA was extracted from each microorganism selected for molecular characterization using the Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Wisconsin, USA) in accordance with the instructions provided by the manufacturer. All the DNA samples were subjected to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification. DNA from the bacteria was amplified using the universal primers 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1495R (5′-CTACGGCTACCTTGTTACGA-3′), which span the V3 region of the 16S rRNA gene49. The DNA from AAB was amplified using primers 16Sd (5′-GCTGGCGGCATGCTTAACACAT-3′) and 16Sr (5′-GGAGGTGATCCAGCCGCAGGT-3′) targeting the 16S–23S rDNA spacer region38. The DNA from yeast was amplified using primers ITS1 (5′-TCC GTA GGT GAA CCT GCG G-3′) and ITS4 (5′-TCC TCC GCT TAT TGA TAT GC-3′), which span the ITS1-5.8S rDNA-ITS2 region25. All PCR reactions were conducted in a final volume of 25μl, comprising 1X of GoTaq® G2 Green Master Mix, 2X (Promega, Wisconsin, USA), 0.5μM of each primer, 3μl of extracted DNA, and water up to the reaction volume. All PCR reactions were conducted in a GeneAmp® PCR System 9700 machine (Thermo Fisher, Massachusetts, USA) under the following conditions for LAB: 1 cycle at 94°C for 5min, 30 cycles at 94°C for 1min, 58°C for 1min, 72°C for 2min, and 72°C for 10min49. For enterobacteria and AMB: 1 cycle at 95°C for 2min, 35 cycles at 95°C for 1min, 50°C for 2min, 72°C for 3min, and 72°C for 7min2. For AAB: 1 cycle at 94°C for 5min, 35 cycles at 94°C for 1min, 58°C for 1min, 72°C for 2min, and 72°C for 10min38. For yeast: 1 cycle at 94°C for 3min, 30 cycles at 94°C for 2min, 60°C for 1min, 72°C for 2.5min, and 72°C for 7min25. PCR products were sequenced by the Institute of Genetics of the National University (IGUN) (Bogota DC, Colombia). The search for similarity among 16S rDNA gene partial sequence from native bacterial strains and the ITS1-5.8S rDNA-ITS2 region from yeast was performed by alignments with sequences from GenBank databases using BLAST software. Native DNA sequences and database reference sequences were aligned using Bioedit 7.7 program. The nucleotide substitution model and evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA1145. The 16S rDNA gene partial sequences were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers: PQ573829.1, PQ568965.1, PQ568962.1, PQ568963.1, PQ568961.1. The ITS1-5.8S rDNA-ITS2 region sequence from yeast was deposited in GenBank under accession numbers PQ289150, PQ289151, PQ289152, PQ289153.

Statistical analysisTo evaluate the physicochemical and microbiological parameters, enzymatic activity and acid production in the selected microorganisms, it was first necessary to evaluate the assumptions of normality (Shapiro–Wilk test) and homoscedasticity (Levene test) of each data set, to determine the appropriate statistical approach. Subsequently, an analysis of variance was performed according to the nature of the data. Parametric analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted, using Fisher's test statistic (homoscedasticity) or Welch's test statistic (heteroskedasticity), while non-parametric analysis was performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test. Furthermore, as a multiple comparison test to determine the formation of groups, the Tukey or Games–Howell test was used. All analyses were performed using Jamovi software, with statistical significance threshold set at 5%.

ResultsComparison between the environmental and physicochemical parameters measured during solid-state coffee fermentationsThe environmental and physicochemical parameters measured during the fermentation processes at the Loma Gorda farm are shown in Supplementary Table S1. As the fermentation progressed, the pH decreased, reaching values close to 4.0 at the end point of fermentation. The °Brix exhibited variations throughout the process, with higher values recorded at the end of fermentation. The average values of environmental and physicochemical characteristics recorded during the solid-state fermentation process of coffee with an average duration of 10h are shown in Table 1. The temperature of the fermentation mass was analyzed by calculating the average of the temperatures (AT) recorded by the three sensors. As shown in Table 1, there are statistically significant differences between all fermentation processes at the level of the measured parameters.

Comparative analysis of the physicochemical parameters evaluated in the spontaneous fermentation processes of coffee

| Parameter | 1108 | 1308 | 1509 | 2107 | 3007 | 1908 | p-Value between groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ET (°C) | 20.9±2.5 | 20.4±2.5 | 19.4±1.0 | 17.2±0.9 | 21.3±2.1 | 18.7±1.2 | <0.001b |

| RH (%) | 72.8±3.3 | 79.9±5.8 | 79.2±2.2 | 98.2±3.2 | 92.3±8.4 | 94.9±3.1 | <0.001b |

| pH | 4.8±0.3 | 4.4±0.2 | 4.3±0.2 | 4.4±0.2 | 4.1±0.1 | 4.4±0.3 | <0.001a |

| °Bx | 15.3±1.4 | 15.8±0.5 | 17.7±0.4 | 17.8±0.7 | 12.7±1.1 | 14.4±1.1 | <0.001a |

| AT (°C) | 23.9±0.1 | 24.7±0.6 | 23.8±0.2 | 20.9±0.3 | 24.1±0.7 | 22.5±0.4 | <0.001b |

As shown in Table 2, the statistical analysis reveals no significant differences in the recorded counts of microbial groups during the solid-state fermentation of coffee, except for enterobacteria counts (p<0.05). The most representative colonies that were isolated and purified are presented in Supplementary Table S1, with a macroscopic and microscopic description. In total, 52 microbial isolates were preserved, comprising 7 of the AMB, 8 of the LAB, 11 of the AAB, 13 enterobacteria and 13 yeasts.

Statistical measures (mean±SD) of the log CFU/g of each microbial group evaluated in solid-state fermentation of coffee

| Microbial group | 1108 | 1308 | 1509 | p-Value between groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMB | 7.00±0.36 | 6.86±0.15 | 7.18±0.24 | 0.18b |

| LAB | 6.82±0.57 | 7.00±0.80 | 6.54±0.30 | 0.49a |

| AAB | 6.04±0.91 | 6.04±0.69 | 6.34±0.26 | 0.81b |

| Enterobacteria | 6.80±0.43 | 6.06±0.28 | 6.38±0.20 | 0.012a |

| Yeast | 6.40±0.61 | 6.50±0.49 | 6.44±0.19 | 0.94a |

SD: standard deviation.

The greatest tolerance to ethanol was demonstrated by AAB and LAB, with yeasts exhibiting only slight reductions in growth, and enterobacteria and AMB displaying notably greater susceptibility to ethanol. The AAB demonstrated the highest tolerance to acetic acid, with a level of resistance comparable to that observed in the majority of AMB isolates; yeast and LAB showed a slight reduction in growth, while enterobacteria exhibited the greatest susceptibility at concentrations above 2%. In terms of temperature, the findings indicated that all yeast isolates evaluated, as well as AMB, LAB and AAB strains, demonstrated the ability to proliferate at temperatures reaching 45°C. In contrast, enterobacteria exhibited susceptibility starting at 25°C. AAB, AMB and LAB showed the best tolerance to pH below 4.0, yeasts were slightly affected by lowering the pH, while enterobacteria showed the lowest tolerance to low pH. In contrast, at pH above 6.0, a reduction in the growth of LAB and AAB was observed, while yeasts and enterobacteria showed greater growth. All microbial isolates evaluated showed growth in media supplemented with glucose, with yeasts exhibiting particularly robust growth. On the other hand, all microbial isolates evaluated showed a reduction in growth in media supplemented with fructose at concentrations above 20%. Since most of the isolates showed tolerance to most of the stress factors evaluated, microorganisms that showed simultaneous tolerance to concentrations of ethanol ≥10%, acetic acid ≥5%, temperature ≥25°C, pH ≤4, fructose and glucose ≥15% were selected for further analysis. These microorganisms are of particular significance in the fermentation process. In this context, four of the 7 AMB isolates, six of the 8 LAB, eight of the 11 AAB, and eleven of the 13 yeast isolates were selected for the enzymatic activity and organic acid production tests (Supplementary Table S2).

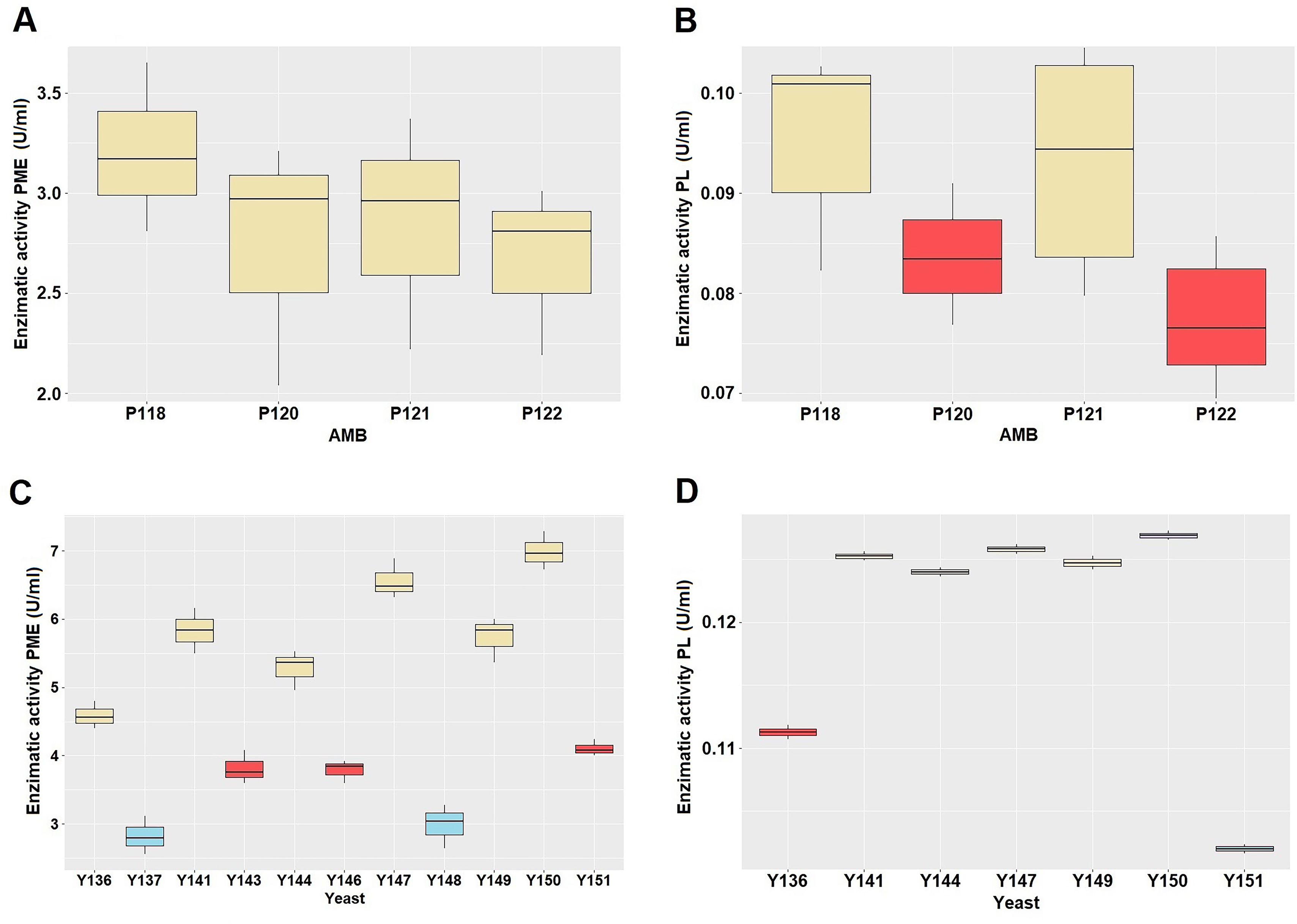

As yeasts are the primary group responsible for pectinolytic activity, followed by AMB, albeit to a lesser extent17, the enzymatic activity was assessed in the four AMB isolates and the eleven yeast isolates selected. No statistically significant differences were observed in the PME activity of the AMB isolates (p>0.05) (Fig. 1A). The PL activity was evaluated in all isolates, indicating statistically significant differences between the two groups (p<0.01), suggesting the presence of two distinct categories. The average value of the enzymatic activity fluctuated between 0.078 and 0.082U/ml, while group 2 exhibited values between 0.098 and 0.101U/ml (Fig. 1B). P118 and P121 were preselected, as they demonstrated a higher enzymatic activity (greater than 0.09U/ml). Notably, isolate P121 exhibited tolerance to elevated concentrations of ethanol and low pH values; therefore, it was finally selected for molecular identification. It was demonstrated that there are statistically significant differences in the PME enzyme activity of each isolate of yeast (p<0.001), with the formation of defined groups observed in the multiple range tests (Fig. 1C). The average value of the enzymatic activity of group 1 fluctuated between 2.82 and 2.98U/ml, group 2 between 3.78 and 4.10U/ml and group 3 between 4.58 and 6.98U/ml (Fig. 1C). Consequently, yeast isolates exhibiting an enzymatic activity greater than 4U/ml (corresponding to Y136, Y141, Y144, Y147, Y149, Y150, and Y151) were selected for the PL analysis. A statistically significant difference in the PL enzyme activity of each yeast isolate was identified (p<0.01) (Fig. 1D). This analysis yielded the identification of four distinct groups. The average value of the enzymatic activity of group 1 was 0.102, group 2 was 0.111U/ml, group 3 fluctuated between 0.124 and 0.125U/ml, while group 4 was 0.126U/ml (Fig. 1D). The yeasts demonstrating PL enzymatic activity greater than 0.12U/ml (Y144, Y147, Y149, and Y150) were selected for further molecular identification.

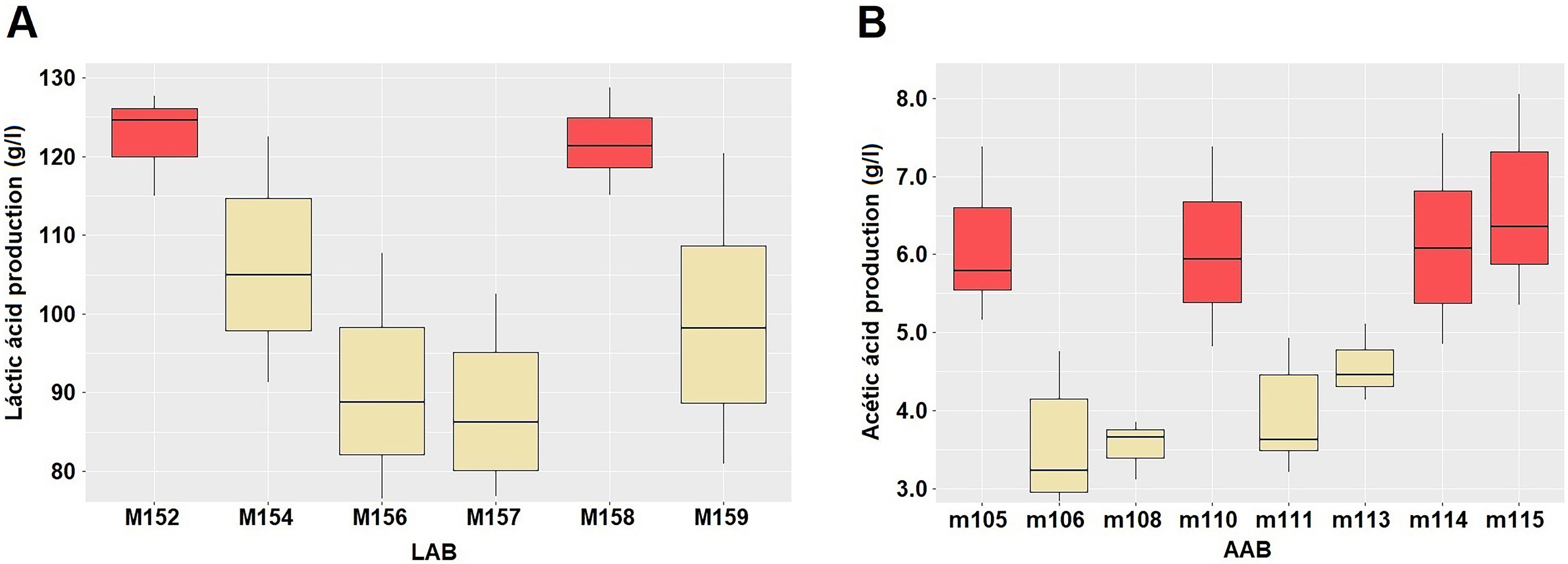

The present study assessed lactic acid production in six preselected LAB isolates. Statistically significant differences in lactic acid production were observed (p<0.001), with two homogeneous groups being formed. The average value of lactic acid production of group 1 fluctuated between 106.95 and 125.62g/l, while that of group 2 presented values between 125.62 and 143.67g/l (Fig. 2A). LAB isolates (M154, M157, M159) that exhibited tolerance to higher ethanol concentrations and low pH values, were selected for molecular identification. These isolates belong to group 2 of lactic acid production. Acetic acid production was assessed in all eight preselected AAB isolates. Statistically significant differences in acetic acid production were observed (p<0.001), with two homogeneous groups being formed. The average value of acetic acid production of group 1 fluctuated between 3.51 and 6.08g/l, and group 2 between 6.03 and 6.57g/l (Fig. 2B). The AAB isolate that demonstrated tolerance to elevated ethanol concentrations and low pH values (m108) was selected for molecular identification and belonged to group 1 of acetic acid production.

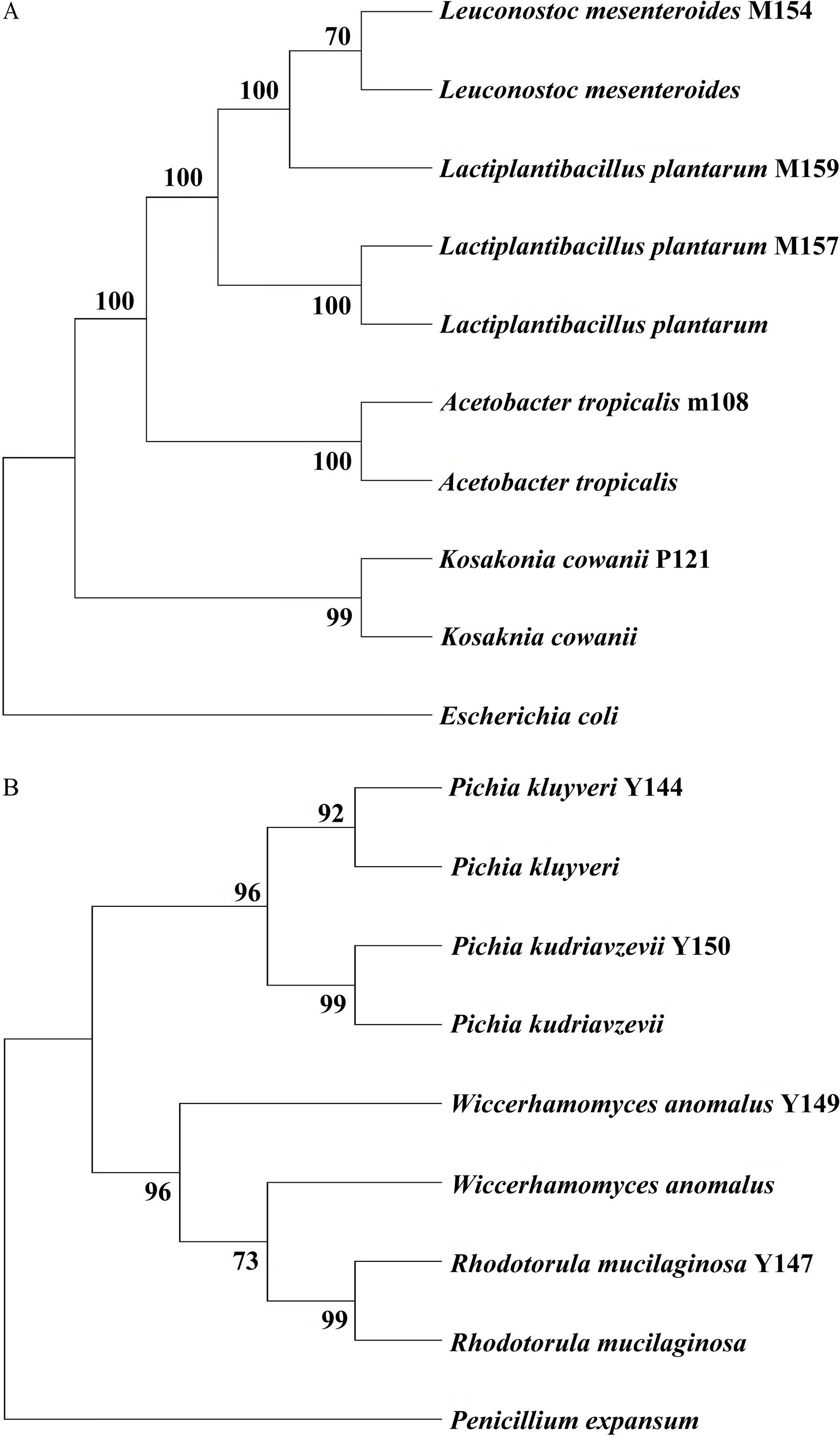

Molecular identification of the bacteria and yeast selected as potential starter culturesThe 16S rDNA gene partial sequence from bacteria was obtained by splicing the 800bp (amplified with 27F and 1495R primers) and 800bp fragments (amplified with 16Sd and 16Sr primers). The m108 bacterial strain exhibited 95% similarity to the Acetobacter tropicalis species, and P121 had 97% similarity with Kosakonia cowanii species. BAL strains M154 and M159 were 85% and 97% similar to the species Leuconostoc mesenteroides, respectively, while M157 was 97% similar to the species Lactiplantibacillus plantarum (formerly known as Lactobacillus plantarum). The ITS region partial sequence from yeast was obtained by splicing the 300 and 600bp (amplified with ITS1 and ITS4 primers). The yeast strains (Y144 and Y150) exhibited a similarity level of over 98% to the species Pichia kluyveri and Pichia kudriavzevii, respectively. Strain Y147 showed a 98% similarity level of to the species Rhodotorula mucilaginosa, while strain Y149 exhibited a 96% similarity level to the species Wickerhamomyces anomalus (W. anomalus). The bacteria included here were grouped into four clusters (Fig. 3A). Strain M154 is more closely related to L. mesenteroides than strain M159, although they form a single cluster. The other sequences of the identified strains form clusters with their respective reference sequences. The yeast strains included in this study were grouped into two clusters, as shown in Fig. 3B. The first cluster consists of Pichia genus strains, which are closely related to the reference sequences for each species. The second cluster comprises yeast strains from the genera Rhodotorula and Wickerhamomyces.

Dendogram of bacterial strain similarity based on analyzing the 16S ribosomal gene (A) and ITS region (B) partial sequences. The nucleotide substitution model and evolutionary analyses were conducted using MEGA11 software. Distance measure: maximum-likelihood resampling method: bootstrap 1000 reps.

The microorganisms identified in the present study as potential starter cultures for coffee fermentation were derived from the 2021 processes. In contrast to enterobacteria, the counts of the other microbial groups remained consistent across all processes evaluated, despite notable differences among the other parameters assessed. Furthermore, enterobacteria were more susceptible to the coffee fermentation microecosystem. Consequently, they demonstrated a tendency to decrease as fermentation progressed5. The soluble solids of the mucilage exhibited variability likely due to the effect of microbial metabolism. Glucose and fructose have been identified as essential sources of carbon and energy for microbial growth. However, the findings of our study indicate that at elevated concentrations of fructose, there is a decline in microbial growth, likely attributable to the challenges these microorganisms face in tolerating the elevated osmotic pressure resulting from fructose. Among other strategies, LAB regulate their carbohydrate metabolism as a strategy to cope with environmental stress23. The response and tolerance to ethanol stress in AAB, LAB, and yeasts may be attributable to different defensive strategies and metabolic adaptations that these microbial groups adopt when producing or using ethanol44. Yeasts carry out alcoholic fermentation, while heterofermentative LAB produce ethanol among other compounds, and the ethanol produced by yeasts is oxidized by AAB13,17,42. In contrast, enterobacteria and AMB may have encountered a form of organic solvent (ethanol) stress, which results in membrane damage, protein denaturation, and elevated oxidative stress44. In this metabolic context, AAB, AMB, yeast, and LAB isolates demonstrated increased tolerance to acetic acid exhibiting the ability to respond to acetic acid stress through multiple mechanisms. This is evidenced by their interaction with weak acids, such as acetic and lactic acids, during fermentation24,41. It is anticipated that enterobacteria isolates would be similarly affected, given the ability of acetic acid to cross the cell membrane and enter the cell, thereby severely inhibiting cell growth and metabolic activities24.

The decrease in pH observed during all coffee fermentations evaluated in this study is indicative of the microbial metabolism that occurs during coffee fermentation, which is driven by the production of metabolites such as lactic acid. In this study, the enhanced low pH tolerance exhibited by LAB and AAB is attributable to their adaptation to the lactic and acetic acids they produce23,24. Yeast employ various mechanisms to cope with weak acid stress and overcome growth inhibition to a certain extent27. However, the neutrophilic nature of enterobacteria poses a significant challenge in their survival under low pH conditions27. The LAB evaluated in our research produced higher concentrations of lactic acid than AAB of acetic acid. In our research, lactic acid concentrations were found to be higher, and acetic acid concentrations were comparable to those observed at the conclusion of coffee solid-state fermentation evaluated by Osorio et al.34. Lactic acid has been demonstrated to influence the breakdown of pectin in coffee pulp1. In addition, it has been shown to modify the sensory perception of acidity and body in coffee beverages9. Acetic acid, at low concentrations, contributes to a pleasant, clean, and sweet taste in coffee. However, at high concentrations (>1mg/ml), it produces a pungent and vinegary note15. Temperatures recorded in the fermentation mass (20.9–24.7°C) have been demonstrated to function as an indicator of fermentation quality, which in turn impacts cup quality34. Furthermore, these temperatures are conducive to the growth of mesophilic microorganisms, whose activity is reported to be optimal at temperatures between 20°C and 45°C28. This provides a rationale for the thermotolerance characteristic that was observed in the different isolates of AAB, LAB, and yeasts23,24.

The PME activity of the evaluated microbial isolates demonstrates their ability to deesterify the methoxyl group of pectin, forming polygalacturonic acid (PGA) and methanol22. The detection of PME activity is of particular significance, as microorganisms do not proliferate on esterified pectins. Consequently, the release of PGA, a substrate for the activity of other enzymes such as polygalacturonase (PG) or pectate lyase (PAL), is enabled1. The activity of these enzymes in microbial isolates should be the focus of future studies. PL activity is another widely used criterion for selecting coffee fermentation yeasts13. PL catalyzes the degradation of pectin by transelimination, releasing unsaturated galacturonic acids22. In the present study, the PL activity of all isolates was found to vary, suggesting a significant role for microorganisms in the degradation of coffee mucilage17. Overall, the pectinolytic activity of yeasts was found to be more robust than that of bacteria, exhibiting stability under various stress conditions. The strains identified in our research, P. kluyveri Y144, P. kudriavzevii Y150, W. anomalus Y149, and R. mucilaginosa Y147, possess the ability to produce both PME and PL activities. Some strains of P. kudriavzevii have been reported to have slightly higher PME enzymatic activity compared to PL enzymatic activity21. In a similar vein, P. kluyveri and P. anomala have been documented to exhibit significant pectinolytic activity, although this activity is attributed to the PG enzyme rather than to PME and PL31. In a similar manner, it has been reported that W. anomalus exhibits PL activity and no PME activity21. In a particular study, W. anomalus was evaluated as a starter co-culture with three distinct strains of P. kluyvery. The resultant coffee exhibited characteristics reminiscent of black tea, honey, lemon, and notably high acidity29. The utilization of any species within the genus Rhodotorula as a starter culture for coffee fermentation remains unknown. Consequently, the strain R. mucilaginosa Y147 represents the first report of this species as a potential starter culture. Although, the capacity of R. mucilaginosa to secrete pectinolytic enzymes under specific oenological conditions has been demonstrated39.

The strains identified in our research, Leuconostoc mesenteroides M154, L. mesenteroides M159, and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum M157, correspond to LAB, a versatile microbial group with useful properties9. However, only recently, L. mesenteroides CCMA1105 and in co-culture with Lcp. plantarum CCMA 1065, Saccharomyces cerevisiae CCMA0543, and Torulaspora delbrueckii CCMA0684, was tested as a starter culture for Arabica and Canephora coffee fermentations3,4. The authors obtained higher-quality coffees with divergent sensory profiles. L. mesenteroides produced a beverage characterized by notes of caramel, fruit, and spices. The strains Lcp. plantarum LPBR01 and MTCC5422, and L. rhamnosus HN001 have been utilized as starter cultures, with the objective of enhancing the quality of the coffee beverage7,12,43,47. No species of Acetobacter and Kosakonia genera have been previously documented in coffee fermentation. Therefore, the strains A. tropicalis m108 and K. cowanii P121 represent a novel report of these species in coffee fermentation. A. tropicalis distinguishes itself from other AAB due to its capacity to produce acetic and gluconic acid from ethanol, though it does not yield substantial amounts of acetic acid compared with other bacteria within the same group38. While the function of Kosakonia in coffee fermentation remains to be elucidated, it has been observed that certain strains possess the capacity to produce lactic acid from agroindustrial waste, in addition to exhibiting high pectinolytic activity during the decomposition of plant material14.

It is also noteworthy that the utilization of diverse culture media proved to be effective, primarily due to the successful establishment of a comprehensive collection of microorganisms isolated from coffee fermentation in the region. The microbial isolates belonging to the genera Acetobacter, Kosakonia, Leuconostoc, Lactiplantibacillus, Pichia, and Wickerhamomyces have been previously reported in coffee fermentation. In particular, the genera Leuconostoc and Pichia are regarded as integral components of the core community involved in this process37. The microorganisms identified in our research may be responsible for the high quality of the coffee produced on the farm where this research was conducted. They are an invaluable resource for coffee growers in the region.

ConclusionsA significant challenge for coffee growers is maintaining and enhancing cup quality throughout the harvesting cycle. Science has made significant contributions to this rural agroindustry by providing a methodology to regulate coffee fermentation through the utilization of starter microbial cultures, which have exhibited a marked improvement in the quality of the final product. The microbial strains characterized and identified in this study represent a substantial addition to the regional knowledge base. These microorganisms were selected not only for their predominance in traditional fermentation processes, such as cherry coffee and solid-state fermentation of depulped coffee, but also for their ability to withstand the various stresses that can arise during coffee fermentation. The characterization and identification of these microorganisms, has generated significant interest in their future utilization as starter cultures. Consequently, coffee producers have the opportunity to enhance the quality and complexity of their products, thereby contributing to the sustainability and economic growth of the region's coffee sector.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

This research was supported by the Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (MINCIENCIAS) [project number 110481865472]. Furthermore, the project entitled “Formación de Capital Humano de Alto Nivel – Universidad de Nariño Nacional” by the Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (MINCIENCIAS) [BPIN 2019000100023], and the Vicerrectoría de Investigaciones e Interacción Social from Universidad de Nariño [project code 2218]. The authors would like to express their gratitude to the coffee producer Guillermo Valencia Burbano (Cuchilla Loma Gorda farm) located in the municipality of Buesaco. He kindly allowed the research team to study the postharvest coffee processing practices at his farm for the production of specialty coffee, providing samples of the coffee cherries, depulped coffee, and mucilage during the fermentation process. Additionally, the research team would like to thank him for allowing the cupping test of their product using dry parchment coffee samples. The authors would also like to express their gratitude to the Departamento de Lingüística e Idiomas at Universidad de Nariño for their assistance in reviewing the translation of the article.