Among the pathogenic fungi of strawberry (Fragaria ananassa Duch.), Botrytis cinerea, a filamentous necrotrophic fungus that causes gray mold, stands out worldwide for its ubiquity and prevalence. Chemical control has been the most effective method used for years to manage B. cinerea in strawberry crops. However, the frequent use of numerous fungicides has increased issues related to pathogen resistance, resurgence, and toxic residues. In this study, we propose the use of the plant growth-promoting bacterium Azospirillum argentinense REC3 and its flagellin AzFlap, whether non-glycosylated or glycosylated, for the control of B. cinerea. We observed that only REC3 inhibited the mycelial growth of B. cinereain vitro, whereas AzFlap had no inhibitory effect. Moreover, REC3 and only its glycosylated flagellin AzFlap contributed to reducing lesions caused by B. cinerea on detached strawberry leaves.

Entre los patógenos de frutilla (Fragaria ananassa Duch.), Botrytis cinerea, un hongo filamentoso necrotrófico que causa la enfermedad del moho gris, se destaca mundialmente por su ubicuidad y prevalencia. El control químico se ha utilizado durante años y ha sido el método más efectivo para manejar B. cinerea en el cultivo de frutilla. Sin embargo, el uso frecuente de numerosos fungicidas ha incrementado los problemas relacionados con la resistencia a los patógenos, el resurgimiento y los residuos tóxicos. En este trabajo proponemos el uso de la bacteria promotora del crecimiento vegetal Azospirillum argentinense REC3 y su flagelina AzFlap, ya sea no glicosilada o glicosilada, para el control de B. cinerea. Observamos que solo REC3 inhibió el crecimiento micelial de B. cinereain vitro, mientras que AzFlap no produjo inhibición. Además, REC3 y solo su flagelina glicosilada AzFlap contribuyeron a reducir las lesiones causadas por B. cinerea en hojas desprendidas de frutilla.

Among the pathogenic fungi of strawberry (Fragaria ananassa Duch.), Botrytis cinerea, a filamentous necrotrophic fungus that causes gray mold, stands out worldwide for its ubiquity and prevalence2. Chemical control has been the most effective method used for years to manage B. cinerea in strawberry crops; however, the frequent use of numerous fungicides has increased issues related to pathogen resistance, resurgence, and toxic residues3. Among the possible alternatives, based on bioinputs, successful use has been reported with Bacillus cereus15, Paenibacillus polymyxa12, the application of extracts from the fungus Colletotrichum acutatum9, or of Streptomyces sp. sdu1201 and its derived compound actinomycin D14.

For the control of B. cinerea, we propose the use of the plant growth-promoting bacterium Azospirillum argentinense REC35, and as a novel finding, its flagellin AzFlap, obtained from its polar flagellum6. Regardless of the presence of A. argentinense REC3, it was observed that its flagellin AzFlap was capable of controlling Macrophomina phaseolina, eliciting defense responses in the plant similar to those triggered when it was inoculated with REC36. REC3 flagellin is a glycosylated protein (100kDa) with elicitor capacity for defense responses in strawberry plants6. However, to date, it remains unknown whether this flagellin confers a differential response in strawberry, specifically in the control of B. cinerea, when applied in its glycosylated or non-glycosylated form. It is known that glycosylated proteins provide mechanisms for controlling signal transduction, protein folding, stability, cell-to-cell interaction, and immune response in the host7. Therefore, based on the background of REC3 and its flagellin, our working hypothesis is that A. argentinense REC3 and its flagellin AzFlap, in its glycosylated form, contribute to reducing lesions caused by B. cinerea on strawberry leaves. To investigate this further, we propose as study objectives to evaluate in vitro the inhibition of B. cinerea growth caused by REC3 and AzFlap, and to assess the incidence of gray mold on strawberry leaves treated with REC3 or its flagellin AzFlap, whether non-glycosylated or glycosylated.

A pure culture of A. argentinense REC3 was grown in NFb liquid medium1, supplemented with 1% NH4Cl for 24h at 30°C and 120rpm. Cells were then centrifuged at 2000×g for 10min and washed twice with sterile double distilled water at pH 7.0 to remove culture medium residues that might interfere with the assays; cells were suspended in sterile double distilled water and the concentration for strawberry leaves inoculation was ∼106CFU/ml (OD560nm 0.2).

Flagellin AzFlap was obtained as described previously6. After denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, following standard procedures, two bands, one of 100kDa and another of 70kDa, were excised from the gel, electroeluted in Tris–glycine buffer pH 8.3 at 40V for 12h, dialyzed, lyophilized, and suspended in distilled water to a 200nM concentration. Both bands correspond to flagellin AzFlap, with the 70kDa band being the deglycosylated version, derived from the extraction process. This was previously confirmed by Western blot using the antibody antiflagellin of A. brasilense Sp7 and by sugar staining using the Shiff method6.

The BMM strain of B. cinerea was used. It was cultivated on potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium (39g/l) at 24°C with 16h of light (200μmol/m/s). After 8–10 days of growth, a conidia suspension (1×104conidia/ml) was prepared by filtration through gauze and quantified using a Neubauer chamber8.

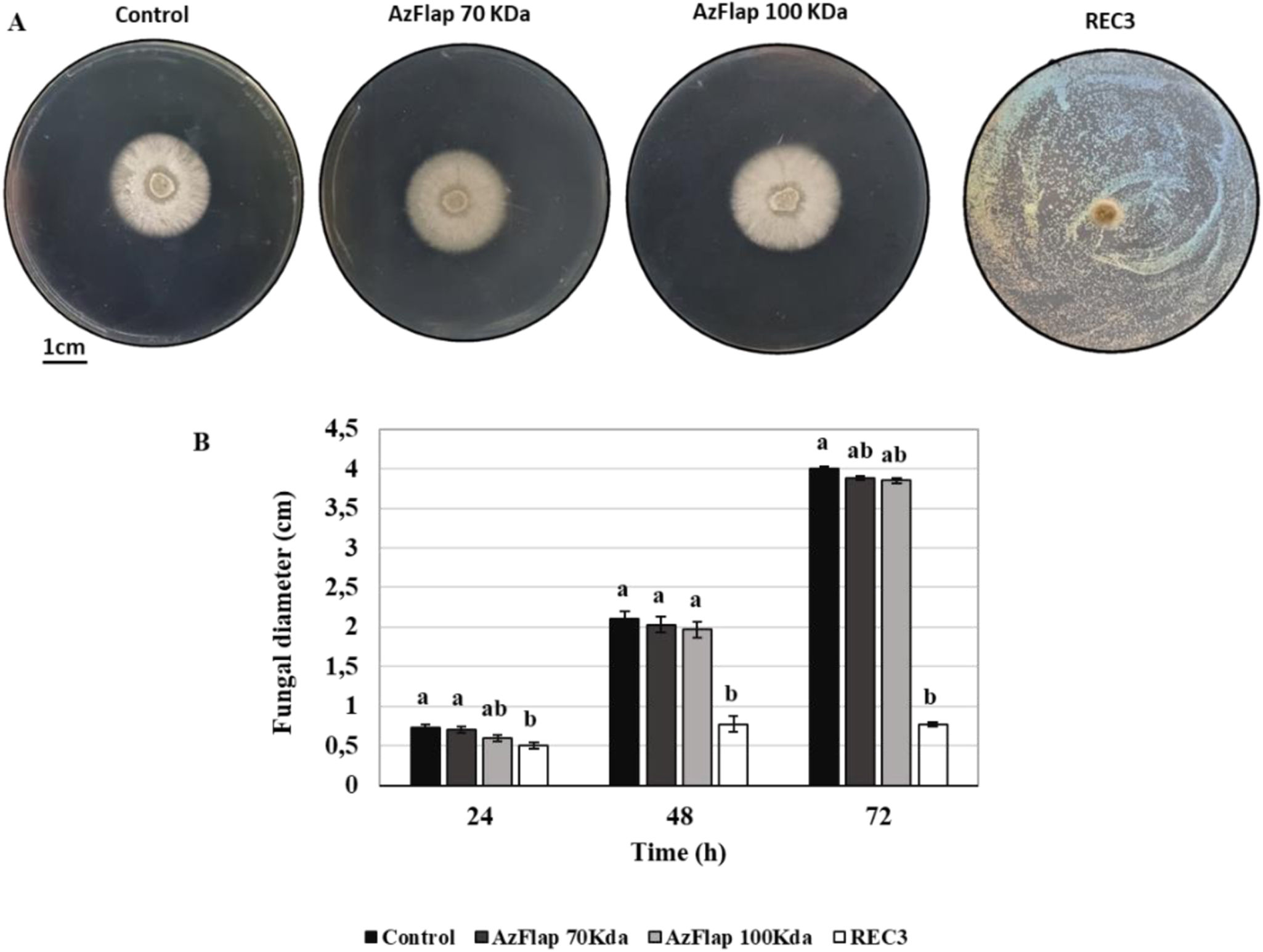

The antifungal activity against B. cinerea growth was assessed on PDA plates (9cm in diameter). One hundred microliters of either AzFlap 70kDa solution (200nM), AzFlap 100kDa solution (200nM), or REC3 suspension (106UFC/ml) was spread evenly over the surface of the PDA plates using a Drigalski spatula until fully absorbed. Afterward, 5μl of the conidia suspension (1×104conidia/ml) was placed in the center of each plate and incubated in darkness at 24°C. Fungal colony diameter (cm) was measured with a caliber at 24, 48, and 72h postinoculation. The experiment was conducted three times, with three replicates per treatment.

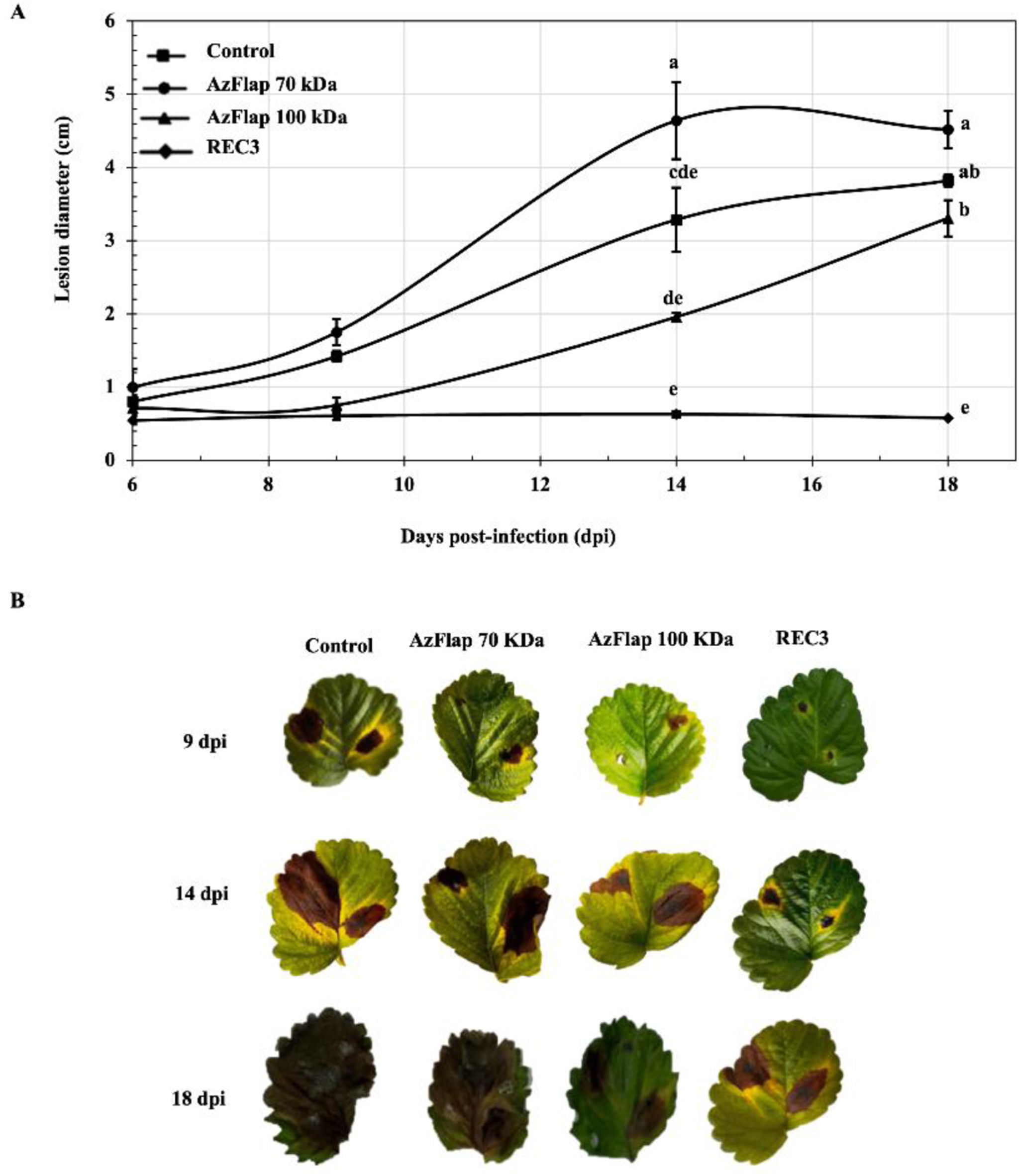

Biocontrol assays were conducted to evaluate the incidence of gray mold on strawberry leaves treated with REC3 and its flagellins. B. cinerea grown on APG medium and detached strawberry leaves, var. Pájaro, 3 months old, were used13. The leaves were surface disinfected with 70% ethanol, and the leaflets were separated and mixed; then, three leaflets were randomly selected for each treatment and placed in Petri dishes on filter paper moistened with sterile water. The treatments were applied by spraying both sides of the leaflet until runoff: sterile water (control); REC3 (∼106CFU/ml); flagellin 70kDa (200nM); flagellin 100kDa (200nM). Three days after the treatments were applied, the leaflets were inoculated on the adaxial side with 0.5cm diameter plugs containing B. cinerea (104conidia/ml). The Petri dishes were placed in a phytotron at photon flux density of 150μmol/m/s (12/12h light/dark cycle) at a relative humidity of 60–70% and 25±2°C for 18 days. At 9, 14, and 18 days post-infection (dpi), the diameter of the lesions caused by B. cinerea was measured. At 18 dpi, disease severity was determined, which consists of the ratio between the damaged area and the total surface of the leaflet, multiplied by 100.

After verifying the normal distribution of the data, the general linear ANOVA model was applied using Infostat statistical software version 20184. Significant differences between mean values were determined by Fisher's pairwise comparisons (p˂0.05)4.

In this study, after conducting the in vitro challenge to evaluate the inhibition of B. cinerea growth caused by A. argentinense REC3 and its glycosylated or non-glycosylated flagellin, it was observed that the bacterium inhibits fungal growth (Figs. 1A and B). This was also previously observed in the inhibition of mycelial growth of C. acutatum and M. phaseolina6,10. In the case of flagellin, neither the glycosylated nor the non-glycosylated form inhibited the growth of B. cinerea (Figs. 1A and B).

In vitro antifungal activity of Azospirillum argentinense REC3, Azflap 70kDa, and Azflap 100kDa. (A) Qualitative examples of mycelial growth inhibition 72h after the assay. (B) Diameter of mycelial growth of B. cinerea observed at 24, 48, and 72h. Vertical bars represent the standard errors of the means. Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences at p<0.05.

Previously, we had reported that flagellin AzFlap, in its glycosylated form, induces a defense response in strawberry plants against the fungus M. phaseolina6. However, to date, AzFlap in its deglycosylated form has not been evaluated. In the biocontrol assay, it was observed that when strawberry leaves were treated with water (control), they developed lesions caused by B. cinerea, expressed as lesion diameter (cm), which increased in size over the 9, 14, and 18 days of the test evaluation (Fig. 2A). However, when REC3 was applied to the leaves, the bacterium was able to control the development of the lesions caused by the fungus during the evaluation period. Figure 2B shows representative pictures of symptoms on strawberry leaves at 9, 14 and 18 days’ post-treatments. This behavior was also observed in strawberry plants inoculated with REC3 and challenged with C. acutatum11 and M. phaseolina6. The mechanisms involved in those cases included plant defense responses expressed at the structural, biochemical, and molecular levels. These mechanisms are also likely involved in the observations with B. cinerea. Regarding the treatments with flagellin AzFlap, it was observed that its deglycosylated form (70kDa) did not reduce the lesions caused by B. cinerea and behaved like the control treatment. However, its glycosylated form (100kDa) significantly (p<0.05) reduced the lesion diameter, although not as much as with the application of REC3 (Figs. 2A and B).

Development of lesions caused by B. cinerea on strawberry leaves, expressed as lesion diameter (cm), at 9, 14 and 18 dpi (A). Vertical bars represent the standard errors of the means. Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences at p<0.05. Bioassay of A. argentinense REC3 and its flagellin AzFlap against B. cinerea on detached strawberry leaves. Representative pictures of symptoms on strawberry leaves under different treatments at 9, 14 and 18 days post-treatments (B).

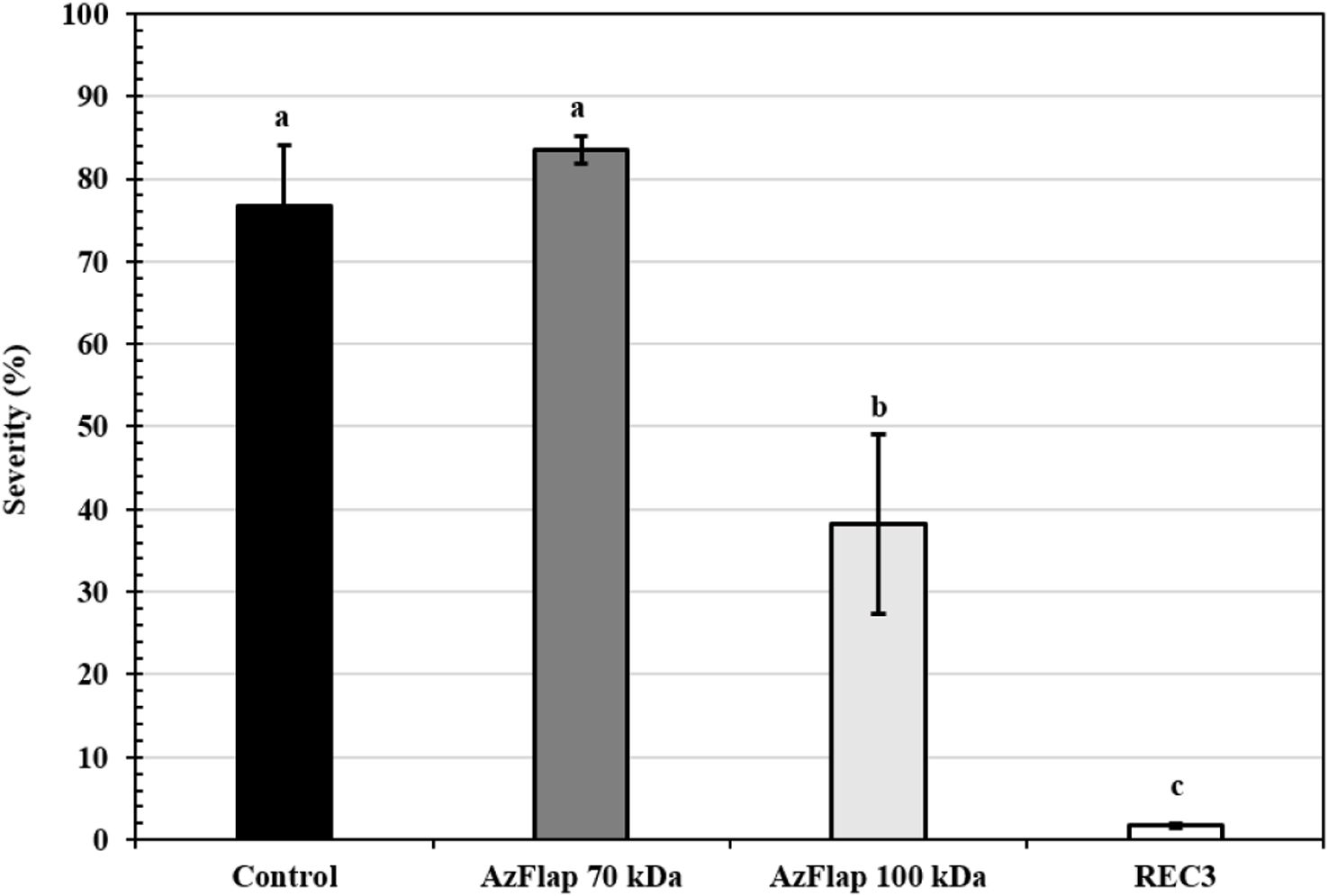

With regard to the severity of the disease, in the treatments with AzFlap, its deglycosylated form (70kDa) did not significantly reduce (83.5%, p<0.05) the lesions caused by B. cinerea and behaved like the control treatment (76.65%, p<0.05). However, its glycosylated form (100kDa) significantly reduced the severity of the disease (38.39%, p<0.05), although not as much as with the application of REC3 (1.67%, p<0.05) (Fig. 3).

Severity of the disease on detached strawberry leaves. The treatments applied were: sterile water (control); flagellin 70kDa (200nM); flagellin 100kDa (200nM); A. argentinense REC3 (∼106CFU/ml). Three days after the treatments were applied, the leaflets were inoculated on the adaxial side with 0.5cm diameter plugs containing B. cinerea (104conidia/ml). Vertical bars represent the standard errors of the means. Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences at p<0.05.

This is the first study to evaluate deglycosylated AzFlap flagellin in a pathological test on strawberry. While the mechanisms involved in these responses have not yet been evaluated, these results suggest that the glycosylation of AzFlap is important in controlling gray mold in strawberry. This, in turn, opens up new possibilities in the search for bioproducts for the control of phytopathogens, independent of bacterial presence, that is, not dependent on the viability of the bacteria to exert a biocontrol effect. Additionally, as observed in the in vitro growth inhibition response of B. cinerea, where AzFlap did not inhibit its mycelial growth, the pathological tests revealed an elicitor action only with glycosylated AzFlap (100kDa), similar to that observed with M. phaseolina6. Therefore, for the biocontrol of B. cinerea, it is important that flagellin AzFlap remains in its glycosylated form. However, further studies on plants will be necessary, including structural analysis of strawberry leaf tissues, as well as the biochemical and molecular aspects involved in the defense response.

FundingThis study was partially funded by Secretaria de Ciencia, Arte y Tecnología, Universidad Nacional de Tucumán (PIUNT A726), and by Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (PICT-2019-02199).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.