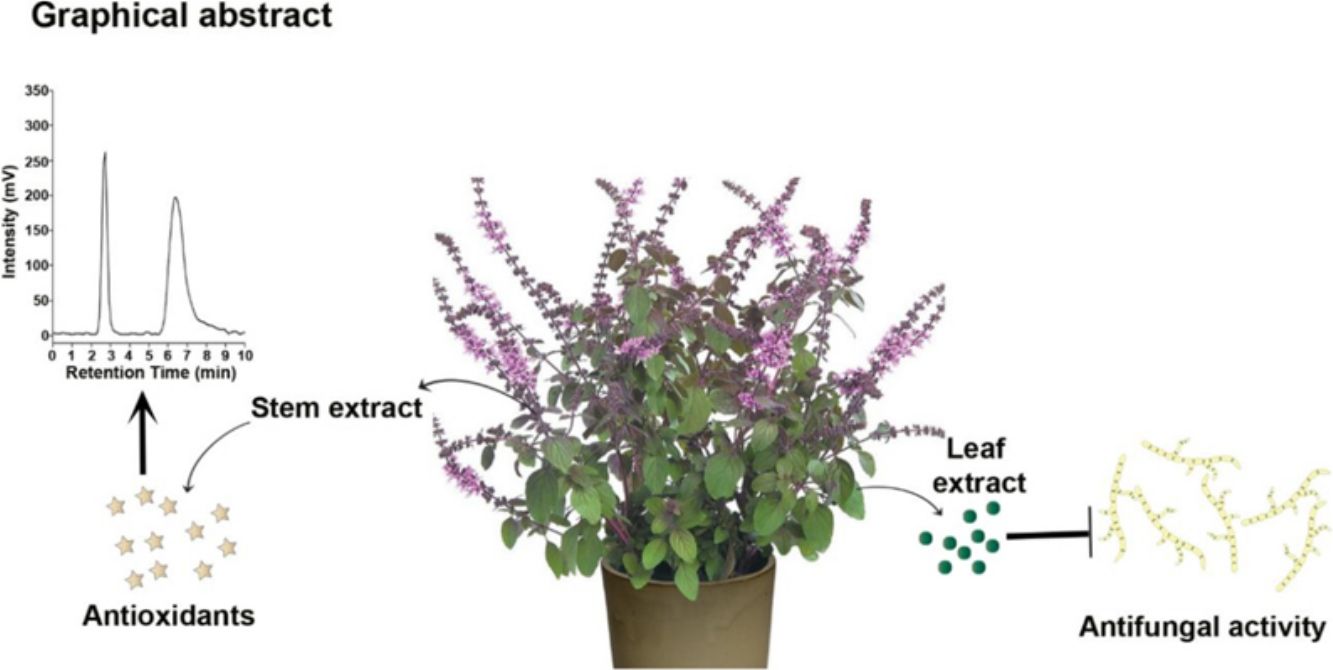

Cicer arietinum L. is a vital source of nutrients that suffers substantial annual losses due to Ascochyta blight, caused by the plant pathogen Ascochyta rabiei. This study aimed to investigate the antifungal potential of Ocimum tenuiflorum L. and O. basilicum L. shoots (leaves and stems) against A. rabiei (Pass) Lab. In vitro bioassays were conducted using methanolic extracts from leaves and stems at six different concentrations: 1%, 1.5%, 2%, 2.5%, 3%, and 3.5%. A total of eight compounds were identified through gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis. The highest inhibition of A. rabiei growth was achieved with a 3.5% methanolic leaf extract of O. basilicum. Methanolic extracts from O. tenuiflorum shoots also reduced fungal growth by 6.18–73%. Additionally, the n-hexane fraction derived from O. basilicum inhibited fungal growth by 71–76% and was subsequently analyzed using GC–MS. This analysis identified eight compounds: (1) cyclopentane, methyl-, (2) cyclohexane, (3) 2,2-dimethylbutane, (4) 2,3-dimethylbutane, pentane, (5) 2,3-dimethyl-, (6) 2-bromoacetonitrile, (7) alpha-cadinol, and (8) phenylpropanolamine. The antioxidant activity of O. tenuiflorum and O. basilicum shoots was also assessed using the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay. The highest antioxidant activity, 98.58%, was recorded at a 3.5% methanolic stem extract concentration of O. tenuiflorum. The antioxidant activity potential was highest for O. tenuiflorum at 0.729mg/mL, followed by O. basilicum at 0.411mg/mL.

El garbanzo (Cicer arietinum L.), una fuente vital de nutrientes sufre pérdidas anuales sustanciales debido al tizón de Ascochyta, causado por el patógeno vegetal Ascochyta rabiei. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo investigar el potencial antifúngico de los brotes (hojas y tallos) de Ocimum tenuiflorum L. y Ocimum basilicum L. frente a A. rabiei (Pass) Lab. Se realizaron bioensayos in vitro utilizando extractos metanólicos de hojas y tallos en seis concentraciones: 1; 1,5; 2; 2,5; 3 y 3,5%. Se identificaron un total de ocho compuestos mediante análisis de cromatografía gaseosa y espectrometría de masas (GC-MS). La mayor inhibición del crecimiento de A. rabiei se logró con un extracto metanólico de hoja de O. basilicum al 3,5%. Los extractos metanólicos de brotes de O. tenuiflorum también redujeron el crecimiento del hongo en una magnitud muy variable: del 6,18 al 73%. Además, la fracción de n-hexano derivada de O. basilicum inhibió el crecimiento del hongo entre el 71-76%. El análisis de dicha fracción mediante GC-MS identificó ocho compuestos: metil-ciclopentano; ciclohexano; 2,2-dimetil-butano; 2,3-dimetil-butano; 2,3-dimetil-pentano; bromo-acetonitrilo; alfa-cadinol y fenilpropanolamina. También se evaluó la actividad antioxidante de los brotes de O. tenuiflorum y O. basilicum mediante el ensayo de 1,1-difenil-2-picrilhidrazilo (DPPH). El potencial de actividad antioxidante fue mayor para O. tenuiflorum con 0,729mg/ml, seguido de O. basilicum con 0,411mg/mL.

Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) is the third most important crop in the Fabaceae family, which is highly valued for its nutrient-rich seeds that contain 25–28% protein15. It also serves as a significant source of vitamins such as niacin, folate, thiamin, riboflavin, and β-carotene, a precursor of vitamin A20. However, chickpea production is frequently compromised by Ascochyta blight, caused by the fungal pathogen Ascochyta rabiei, belonging to the Ascomycetes class. This fungus produces brown spots on the lower stems of emerging seedlings, which enlarge and encircle the stem, ultimately weakening it and causing plant death29.

On the other hand, integrated disease management strategies are vital for effectively managing A. blight4. Common control measures include tillage, crop rotation14, and the application of foliar fungicides12,33. Additionally, the use of economically viable, blight-resistant varieties offers another effective approach. The application of fungicides, such as foliar sprays and seed treatments, can eliminate A. rabiei. However, these chemical pesticides pose risks to farmers, end-users, and non-target beneficial organisms26. Growing environmental concerns have driven a shift from synthetic pesticides to biological control agents, particularly plant-based products. Numerous studies have highlighted the use of plant extracts to combat harmful plant pathogens1,5–7. Laboratory and field-based plant-derived pesticides represent a promising alternative to synthetic fungicides, offering effective pathogen control while minimizing environmental impact and risks to human health.

Ocimum plants are culinary and fragrant ornamental species thriving in tropical and subtropical regions, known for their antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. Numerous studies have highlighted their pharmacological benefits, including cardioprotective, anti-diabetic, and anticancer activities13. These plants are also valued for their diverse metabolites, medicinal applications, and nutraceutical potential40. Additionally, the genus exhibits antimicrobial32, insecticidal, antifungal, antiparasitic, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, hepatoprotective, neuroprotective, anti-osteoporotic, and other health-promoting effects, which have garnered increasing scientific and therapeutic interest24.

Ocimum tenuiflorum (L.), commonly known as tulsi, is a perennial aromatic plant from the mint family (Lamiaceae) native to the Indian subcontinent36. It is rich in bioactive compounds such as eugenol (70%), β-caryophyllene (approximately 8%), rosmarinic acid, linalool, carvacrol, ursolic acid, and oleanolic acid8. Similarly, O. basilicum (L.), commonly referred to as basil or sweet basil, is a well-known herb in the Lamiaceae family. It contains rosmarinic acid as a key bioactive component, which exhibits therapeutic effects against various infections25,38 and possesses potent antioxidant, anticancer, antimicrobial, and antiviral properties10,11.

The aim of the current study is to evaluate the antifungal and antioxidant potential of Ocimum species, specifically O. tenuiflorum and O. basilicum, against A. rabiei (Pass) Lab, the causative agent of A. blight in chickpea, and to identify the bioactive compounds responsible for these activities.

Materials and methodsCollection of plant materialsO. tenuiflorum and O. basilicum were collected from the Botanical Garden of Lahore College for Women University, Lahore, Pakistan (permission was obtained from the Head of Department). The shoots (stems and leaves) were surface-sterilized using a 1% NaClO solution, followed by thorough rinsing with tap water. Subsequently, the shoots were sun-dried and stored in polythene bags for further analysis and screening.

Fungal culture and species identificationPotato dextrose agar (PDA) medium was prepared at a concentration of g/L by combining 7g of potato dextrose, 10g of agar, and 2.5g of peptone, adjusted to pH 5.0. Prior to autoclaving at 121°C for 20min. The MIC (mg/L) of streptomycin (200mg/L), an antibacterial agent was added to the medium according to CLSI guidelines9. Following autoclaving, the medium was cooled for 15min, poured into petri plates, and allowed to solidify. To isolate A. rabiei, a sample from a diseased chickpea plant infected with chickpea blight was collected from the field. Petri plates containing the fungal mycelium were incubated at 20°C for four days. The single isolated strain was used in the current study.

Morpho-anatomical and molecular identification of A. rabieiThe A. rabiei culture was grown on PDA plates at room temperature (20°C) in darkness for two weeks for morphological examination. Colony characteristics and growth rates were monitored daily. For conidiomata quantification, fungal discs were macerated in 10mL of distilled water, and conidia were counted using a hemocytometer. Morphological and anatomical identification was performed using the keys provided by Visagie et al.41 and examined under a compound microscope at 100× magnification.

Taxonomic identification of A. rabiei was further confirmed through sequencing of the ITS regions. DNA extraction was conducted following the protocol described by Peterson.30 The internal transcribed spacer (ITS1-5.8S-ITS2) region was amplified via PCR using ITS4 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′) as the reverse primer and ITS5 (5′-GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG-3′) as the forward primer. Nucleotide sequences were aligned using MAFFT v.7 and subsequently trimmed with the BioEdit software. The final alignment, after trimming, consisted of 575 sites. A maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was then constructed using the MEGA 10 software.

In vitro bioassay and screeningThe in vitro evaluation of O. tenuiflorum and O. basilicum (leaves and stems) against the test fungus A. rabiei was carried out following the protocol from a previous study42-45. The shoots (stems and leaves) of both plants were sun-dried and ground into powder. At room temperature, 20g of each plant part was soaked in 100ml of methanol for one week. After the soaking period, the plant material was filtered using a sterilized muslin cloth and left to evaporate at room temperature until a gummy mass of 2.1g was obtained. Stock solutions of 20% were then prepared by dissolving 10.5mL of distilled water into the extracts, which were stored at 4°C26.

Five concentrations (1%, 1.5%, 2%, 2.5%, 3%, and 3.5% v/v) of the methanolic extracts were prepared. To prevent bacterial contamination, a streptomycin capsule was added to each flask. From each concentration, 5mL of media was transferred into conical flasks, with all concentrations replicated three times. The test fungus A. rabiei was inoculated from a one-week-old pre-cultured sample. The growth reduction percentage of the fungus was calculated using the following formula:

Fractional guided bioassayForty grams of powdered O. basilicum leaf material was soaked in 200mL of methanol for seven days. The resulting extract was allowed to evaporate at room temperature. The extract was then partitioned using a separating funnel containing four organic solvents: ethyl acetate, chloroform, n-hexane, and n-butanol. The evaporated fractions yielded gummy masses of chloroform (0.6g), n-hexane (0.7g), n-butanol (0.2g), and ethyl acetate (0.2g).

The antifungal activity of these four fractions against A. rabiei was assessed in vitro using the serial dilution method. Two concentrations (0.10% and 0.20%) were prepared for each organic fraction and a fungicide control, following the protocol from a previous study18. Distilled water without any plant extract was used as the control treatment. Each concentration was replicated three times.

GC–MS analysisThe bioassay conducted earlier confirmed that the n-hexane fraction was the most effective. Therefore, the n-hexane fraction was selected for the GC–MS analysis. Forty grams of crushed O. basilicum leaves was soaked in 150mL of methanol for seven days at ambient temperature. The extract was filtered, evaporated, and partitioned with n-hexane. The resulting n-hexane fraction was further filtered using a microporous filter membrane (0.22μm).

The GC–MS analysis was conducted using a QP 2010 chromatograph equipped with a BD-5 capillary column (30m×0.25mm×0.25μm). The injection temperature was set at 50°C with an ionizing intensity of 70eV and a scan range of 55–950Da (m/z).

The oven conditions were programmed as follows: an initial temperature of 45°C was maintained for 1min, then increased to 100°C at a rate of 5°C per minute and kept for 1min. Subsequently, the temperature was raised to 200°C at 10°C per minute and maintained for 5min. Helium (He) was used as the mobile phase. The injector and detector temperatures were set at 200°C and 250°C, respectively.

The percentage composition of volatile compounds was determined based on GC peak area data. Compound identification was achieved by comparing mass spectra, indices, and retention times using reference data from the NIST Library 2010 software22.

Antioxidant activityThe DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl) radical scavenging assay was conducted to evaluate antioxidant potential following the methodology from a previous study16. Four percent stock solutions of both plants (O. tenuiflorum and O. basilicum) were prepared for antioxidant activity. The antioxidant activity was measured by mixing DPPH (2ml of 0.05mM methanol solution) with 1mL of each plant part at various concentrations (3.5%, 3%, 2.5%, 2%, 1.5%, 1%) at room temperature for half an hour. A control sample, containing only methanol without the plant extract, was used as the 0% baseline. The absorbance of the reaction mixtures was measured at 517nm. A color change in the reaction mixture indicated the presence of antioxidant activity. The percentage reduction of the DPPH radical was calculated using the following formula:

In this formula, A0 represents the absorbance of the control, while As corresponds to the absorbance of the test sample. A reduction in test sample absorbance, compared to the positive control, indicated antioxidant activity. The half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value, representing the concentration required to inhibit 50% of the DPPH radicals, was calculated for all samples. The antioxidant activity of the plant extracts was expressed in terms of IC50 values (mg/ml), with Trolox serving as the standard control.

Statistical analysisThe data are presented as means±standard deviations based on at least three independent experiments. Significant differences between treatments were assessed using ANOVA at a significance level of p=0.05, performed with Statistica software (version 12.0, StatSoft Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). Principal component analysis (PCA), ANOVA, and correlation analysis were conducted at a significance level of α=0.05. PCA was applied to explore the relationships among variables and patterns in the data. The optimal number of principal components was determined using Cattell's scree test criterion, and the input matrix was automatically scaled for analysis.

ResultsA pathogenic strain of A. rabiei isolated from a diseased chickpea plant was preliminarily identified using the identification keys provided by a previous study23. The observations included fungal mycelium intensity, colony color and diameter (mm), as well as fungal characteristics (Figs. 1A–F). The conidiomata counts were conducted by cutting a central disc of the culture at a 1mm distance from the center after five days of incubation. The colony color ranged from white-grayish to pure white, while the pycnidia exhibited a slaty gray color with increased intensity at the margins. Quantification revealed conidia and conidiomata densities of 3.5×105 and 78.8/cm2, respectively. The measured sizes of conidia and conidiomata were 13.5μm×6.4μm and 263.5μm×180.9μm, respectively.

In this study, A. rabiei was identified through phylogenetic tree analysis (Fig. 2). The consensus sequence of A. rabiei, along with sequences from closely related species within the genus obtained from the literature and the NCBI, was used for species identification. The consensus sequence of this fungus was submitted to GenBank under accession number OR708537.

The evolutionary history was analyzed using the maximum likelihood method with the Tamura 3-parameter model39. The tree with the highest log likelihood (−1086.87) is presented, showing the percentage of trees where taxa clustered together. Initial trees were generated by the Neighbor-Join and BioNJ algorithms, selecting the topology with the best log likelihood. A rate variation model allowed for 1.80% of sites to remain evolutionarily invariable ([+I]). The tree is scaled by branch lengths representing substitutions per site. The analysis included 24 nucleotide sequences, excluding positions with less than 95% site coverage, resulting in 244 positions in the final dataset. MEGA X was used for the analyses21.

This study investigated the antifungal potential of methanolic extracts from the leaves and stems of O. tenuiflorum and O. basilicum. Data on the antifungal activity of O. tenuiflorum leaf methanolic extract against A. rabiei are presented (Fig. 3A). The highest reduction in fungal biomass (23.78%) was observed at a concentration of 3.5%. Similarly, concentrations of 2.5% and 1.5% suppressed A. rabiei biomass by 19.16%. Other tested concentrations, including 3%, 1%, and 2%, also inhibited fungal growth, with inhibition rates of 15.7%, 11.54%, and 11.54%, respectively, compared to the control treatment.

The antifungal activity of methanolic extracts from O. tenuiflorum leaves (A) and O. basilicum stems (B) on the in vitro growth of A. rabiei is shown here. Vertical bars indicate the standard error of three replicates. Different letters denote statistically significant differences, determined using the LSD test (p=0.05). (C) The impact of organic fractions (n-hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, and n-butanol) derived from O. basilicum leaf extracts on the in vitro growth of A. rabiei is presented. Vertical bars represent the standard error of three replicates, with different letters indicating significant differences, as determined by the LSD test.

For O. basilicum, the methanolic stem extract demonstrated significant antifungal activity against the test fungus. The 3.5% concentration achieved the highest biomass reduction, inhibiting fungal growth by 73%. The concentrations of 3%, 2.5%, 1.5%, and 2% also effectively suppressed fungal biomass, with inhibition rates ranging from 65% to 46%. The 1% concentration showed the least inhibition, reducing fungal growth by 42.6% (Fig. 3B).

O. basilicum leaves exhibited significant antifungal activity against A. rabiei, leading to the selection of this plant part for further investigation. Various organic fractions, including n-butanol, chloroform, ethyl acetate, and n-hexane, were isolated from the O. basilicum extract. In the in vitro bioassay, the n-hexane fraction demonstrated the strongest activity against A. rabiei compared to the other fractions. The highest reductions were observed with the two applied concentrations of n-hexane (0.1% and 0.2%), showing inhibition rates of 71% and 76%, respectively (Fig. 3C).

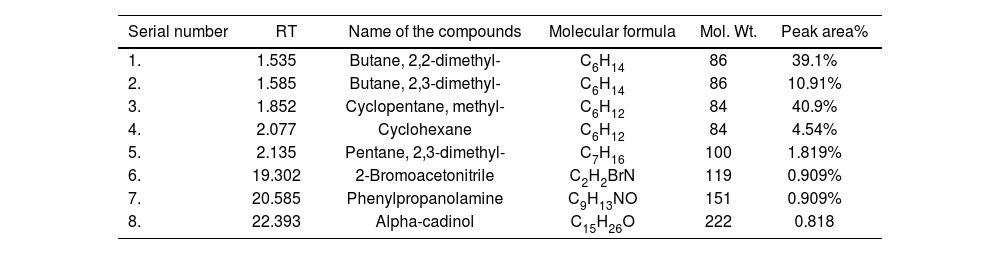

The GC–MS analysis was conducted to identify bioactive phytochemicals in the effective n-hexane fraction of O. basilicum leaves. Eight bioactive compounds were identified, along with their molecular formulas, molecular weights, and peak areas. The identified compounds include: butane, 2,2-dimethyl- (39.1%), butane, 2,3-dimethyl- (10.91%), cyclopentane, methyl- (40.9%), cyclohexane (4.54%), pentane, 2,3-dimethyl- (1.819%), 2-bromoacetonitrile (0.909%), phenylpropanolamine (0.909%), 1,3,7,2,4a,8a,4,8-octahydro, 1,6-dimethyl-4(1-methylethyl), and alpha-cadinol (0.818%) (Table 1).

GC–MS characterization of n-hexane extract of O. basilicum (leaves).

| Serial number | RT | Name of the compounds | Molecular formula | Mol. Wt. | Peak area% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 1.535 | Butane, 2,2-dimethyl- | C6H14 | 86 | 39.1% |

| 2. | 1.585 | Butane, 2,3-dimethyl- | C6H14 | 86 | 10.91% |

| 3. | 1.852 | Cyclopentane, methyl- | C6H12 | 84 | 40.9% |

| 4. | 2.077 | Cyclohexane | C6H12 | 84 | 4.54% |

| 5. | 2.135 | Pentane, 2,3-dimethyl- | C7H16 | 100 | 1.819% |

| 6. | 19.302 | 2-Bromoacetonitrile | C2H2BrN | 119 | 0.909% |

| 7. | 20.585 | Phenylpropanolamine | C9H13NO | 151 | 0.909% |

| 8. | 22.393 | Alpha-cadinol | C15H26O | 222 | 0.818 |

Antioxidants neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated during biological reactions. The antioxidant activity of the methanolic leaf and stem extracts from O. tenuiflorum and O. basilicum was assessed using the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay. At a concentration of 3.5%, the methanolic stem extracts of O. tenuiflorum and O. basilicum exhibited the highest antioxidant activities, with values of 98.58% and 88.89%, respectively. In contrast, the lower concentration (1%) showed minimal antioxidant activity, with values of 66% and 65%, respectively (Figs. 4A and B).

In the current study, the antioxidant activity of crude extracts from Ocimum species at different concentrations (mg/mL) was evaluated using the DPPH method. The antioxidant activity of all Ocimum leaf extracts was investigated, and the results were expressed as IC50 values, including those of Trolox as a standard reference. Notably, the antioxidant activity observed in these species closely resembled that of the Trolox standard, suggesting that these crude extracts contain potent antioxidant compounds that merit further investigation. The results demonstrated that O. tenuiflorum exhibited higher antioxidant activity than O. basilicum against A. rabiei. Additionally, IC50 values for both species were calculated using DPPH, with O. tenuiflorum showing an IC50 of 0.729mg/ml and O. basilicum having an IC50 of 0.411mg/mL (Figs. 4C and D).

The results of the PCA analysis describe the effects of O. tenuiflorum leaf methanolic extract and O. basilicum stem methanolic extract on the in vitro growth of A. rabiei, as well as the antioxidant activity of both species at different concentrations. Four new variables were derived, with the first two principal components accounting for 98.99% of the total variability. PC1 accounts for 94.06% of the variability, and PC2 for 4.93%. As shown in Figure 5A, all parameters significantly contribute to the variability of the system, as they fall within the red circle. A strong positive correlation was observed between the fungal biomass influenced by O. tenuiflorum leaf methanolic extract (OLME) and O. basilicum stem methanolic extract (OBE) on A. rabiei growth. Additionally, a strong positive correlation was found between the antioxidant activities of O. tenuiflorum and O. basilicum at various concentrations. A robust negative correlation was identified between fungal biomass from both extracts (OLME and OBE) and the antioxidant activity of O. tenuiflorum and O. basilicum at different concentrations. The PCA analysis indicated that the positive values of the first principal component (PC1) correspond to the zero concentration, while the negative values reflect the presence of concentrations (Fig. 5B).

(A) Loading plot and (B) score plot of the principal component analysis (PCA), illustrating the first (PC1) and second (PC2) principal components for the treatments and research parameters. Similarly, (C) loading plot and (D) score plot of the PCA display the first (PC1) and second (PC2) principal components for the treatments and research parameters.

Table S1 presents the correlation matrix showing the effect of O. tenuiflorum leaf methanolic extract and O. basilicum stem methanolic extract on the in vitro growth of A. rabiei, as well as the antioxidant activity of O. tenuiflorum and O. basilicum at different concentrations. PCA analysis was also performed to assess the impact of O. basilicum leaf organic fractions (n-hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, and n-butanol) on the in vitro growth of A. rabiei. The determinant of the correlation matrix indicates the collinearity (correlation) of the explanatory variables. A value closer to 0 suggested a lower degree of correlation, while a value closer to 1 indicated a stronger correlation. The sign of the correlation determined its direction, either positive or negative (Table S2). PCA analysis was conducted to examine the effect of O. basilicum leaf organic fraction extracts on the in vitro growth of A. rabiei for n-hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, and n-butanol. Three new variables were derived, with the first two principal components accounting for 99.98% of the total variability in the system. PC1 explained 85.91% of the variability of the system, while PC2 accounted for 14.07%. All parameters significantly influence the variability of the system, as indicated by their position within the red circle (Fig. 5C). A strong positive correlation was found between FCD n-butanol (effect of O. basilicum leaf organic fraction extracts on A. rabiei growth for n-butanol) and FCD chloroform (effect of O. basilicum leaf organic fraction extracts on A. rabiei growth for chloroform) (Fig. 5D). A slightly weaker, yet positive, correlation was observed between FCD n-butanol, FCD chloroform, FCD ethyl acetate (effect of O. basilicum leaf organic fraction extracts on A. rabiei growth for ethyl acetate), and FCD n-hexane (effect of O. basilicum leaf organic fraction extracts on A. rabiei growth for n-hexane). Positive PCI values indicate the presence of fungicide, while negative values correspond to the control. Positive PC2 values correspond to concentrations, while negative PC2 values described the control and fungicide.

Table S2 presents the correlation matrix illustrating the effects of O. basilicum leaf organic fraction extracts on the in vitro growth of A. rabiei for n-hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, and n-butanol. The determinant of the correlation matrix indicates the collinearity correlation) among the explanatory variables. A value closer to 0 denoted a lower degree of mutual correlation, while a value closer to 1 indicated a stronger correlation. The sign of the correlation determines its direction.

DiscussionThe present study investigated the antifungal and antioxidant properties of methanolic extracts from O. basilicum (Niazbo) and O. tenuiflorum against the pathogenic strain A. rabiei. Both plants exhibited significant antifungal activity, with O. basilicum methanolic leaf extract showing the highest inhibition. These findings align with earlier studies4,19, which attributed the antifungal activity of other plant extracts to their phenolic and tannin components. The strong antifungal properties of Ocimum species are likely linked to their secondary metabolites, including flavonoids, tannins, saponins, and glycosides, as suggested by previous studies3,27,28,34.

The study also highlighted the potential of O. basilicum in bioassays, particularly with its n-hexane fraction demonstrating the highest inhibitory activity against A. rabiei (71–76%) at 0.1% and 0.2% concentrations. In line with the present study, previous research37 investigated the various concentrations (1%, 2.5%, 4%, 5.5%, and 7%) of methanolic extracts from Chenopodium album leaves against A. rabiei. The highest reduction in fungal biomass (68%) was observed at a 7% concentration. Additionally, the methanolic leaf extract was partitioned into fractions based on polarity, including n-butanol, chloroform, n-hexane, and ethyl acetate. The antifungal activity of these fractions was evaluated using the serial dilution method, with the n-hexane fraction showing the most significant antifungal potential, achieving 55% biomass inhibition. The subsequent gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis of the n-hexane fraction identified 13 compounds, including aromatic hydrocarbons, saturated fatty acids, aromatic carboxylic acids, siloxanes, phosphonates, and cardiac glycosides37. Similarly, another study39 on the essential oils of O. basilicum. revealed seasonal variations in chemical composition, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities. The oil yield was highest in winter (0.8%) and lowest in summer (0.5%). Linalool was the dominant compound (56.7–60.6%), followed by epi-α-cadinol, α-bergamotene, and γ-cadinene. Winter samples were enriched with oxygenated monoterpenes (68.9%), while summer samples had higher sesquiterpene hydrocarbons (24.3%). Seasonal differences significantly influenced chemical composition (p<0.05). Notably, the essential oils showed strong antioxidant activity, assessed through DPPH scavenging, β-carotene bleaching, and inhibition of linoleic acid oxidation. Antimicrobial tests revealed effectiveness against bacterial strains (Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, and Pasteurella multocida) and fungi (Aspergillus niger, Mucor mucedo, Fusarium solani, Botryodiplodia theobromae, and Rhizopus solani). Therefore, both antioxidant and antimicrobial activities were significantly affected by seasonal changes (p<0.05)17.

In addition to antifungal effects, the study confirmed the strong antioxidant potential of both O. tenuiflorum and O. basilicum. Antioxidant activity was notably higher in the stem extracts than in the leaves. The highest antioxidant activity (98.58%) was observed in the methanolic stem extract of O. tenuiflorum. The phytochemical analysis suggests that flavonoids, alkaloids, terpenoids, and tannins are the primary contributors to antioxidant activity. Similar to the current study, a previous investigation extracted secondary metabolites from dried leaf powder of O. basilicum (green tulsi), O. gratissimum L. (jungli tulsi), and O. tenuiflorum (black tulsi) using acetone, ethanol, methanol, and water. The biological activities, including antioxidant, anti-diabetic, and anti-inflammatory properties, were evaluated in extracts prepared with these solvents. Notably, the acetone extracts of all Ocimum species exhibited the highest total antioxidant activity, ranging from 28 to 429 AAE/g DW, with black tulsi showing the maximum activity (429 AAE/g DW), followed by jungli tulsi (44 AAE/g DW) and green tulsi (28 AAE/g DW). Ethanolic extracts demonstrated the highest scavenging activity (67–85%), with green tulsi being most effective (85%), followed by jungli tulsi (75%) and black tulsi (67%). Comparatively, methanolic and aqueous extracts showed lower antioxidant and scavenging activities. The antioxidant efficacy of tulsi extracts in this study is likely attributed to phenolics, flavonoids, and other bioactive compounds, underlining their potential as therapeutic agents to mitigate oxidative stress and free radical-related diseases35. Similar to this findings, other studies also identified Ocimum species as valuable sources of natural antioxidants with therapeutic potential for combating reactive oxygen species (ROS) and preventing associated diseases2,23,31.

Overall, this study underscores the potential of O. basilicum and O. tenuiflorum as eco-friendly sources of antifungal agents and natural antioxidants. The identification of bioactive compounds with significant pharmacological properties further suggests their potential for developing natural therapeutics in agriculture and medicine. Future research could explore their synergistic effects, optimization for large-scale applications, and deeper insights into their mechanisms of action.

ConclusionThis study highlights the potential of O. tenuiflorum and O. basilicum shoots (leaves and stems) as effective antifungal and antioxidant agents. Methanolic extracts from these plants demonstrated significant inhibition of A. rabiei growth, with the highest antifungal activity observed in the 3.5% leaf methanolic extract of O. basilicum. Similarly, O. tenuiflorum methanolic shoot extracts suppressed fungal growth by 6.18–73%, further supporting their antifungal efficacy. The n-hexane fraction of O. basilicum inhibited fungal growth by 71–76%, and the GC–MS analysis identified eight bioactive compounds, including cyclopentane, cyclohexane, and alpha-cadinol, which may contribute to its antifungal properties. Moreover, antioxidant assays revealed that O. tenuiflorum methanolic stem extract exhibited the highest antioxidant activity at 98.58% with a 3.5% concentration. The maximum antioxidant activity potential for O. tenuiflorum and O. basilicum was 0.729mg/mL and 0.411mg/mL, respectively, indicating their capacity as natural antioxidants.

Overall, these findings demonstrate that O. tenuiflorum and O. basilicum possess promising antifungal and antioxidant properties, making them valuable candidates for developing eco-friendly treatments to manage A. rabiei infections and for potential applications in agriculture and food preservation. Further research could explore the synergistic effects of these bioactive compounds and their mechanisms of action.

CRediT authorship contribution statementConceptualization, TS, KJ, AU; methodology, AU, MSE, RMA; software, AU, SI, KJ; validation, TS, AU, LD; investigation, KJ; resources, MSE, SI; writing original draft preparation, all authors; writing review and editing, AU, SG, KJ; supervision, AU, SI, MSE, RI. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Consent to participateNot applicable.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

Ethical approvalNot applicable.

FundingNone declared.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availabilityThe data will be available from corresponding author on personal request. The sequences are deposited in Genbank can be provided from the first author on request.

The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2025R418), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

![The evolutionary history was analyzed using the maximum likelihood method with the Tamura 3-parameter model39. The tree with the highest log likelihood (−1086.87) is presented, showing the percentage of trees where taxa clustered together. Initial trees were generated by the Neighbor-Join and BioNJ algorithms, selecting the topology with the best log likelihood. A rate variation model allowed for 1.80% of sites to remain evolutionarily invariable ([+I]). The tree is scaled by branch lengths representing substitutions per site. The analysis included 24 nucleotide sequences, excluding positions with less than 95% site coverage, resulting in 244 positions in the final dataset. MEGA X was used for the analyses21. The evolutionary history was analyzed using the maximum likelihood method with the Tamura 3-parameter model39. The tree with the highest log likelihood (−1086.87) is presented, showing the percentage of trees where taxa clustered together. Initial trees were generated by the Neighbor-Join and BioNJ algorithms, selecting the topology with the best log likelihood. A rate variation model allowed for 1.80% of sites to remain evolutionarily invariable ([+I]). The tree is scaled by branch lengths representing substitutions per site. The analysis included 24 nucleotide sequences, excluding positions with less than 95% site coverage, resulting in 244 positions in the final dataset. MEGA X was used for the analyses21.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03257541/0000005700000002/v1_202505020500/S0325754125000306/v1_202505020500/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr2.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)