To assess the associations between EWGSOP2-defined sarcopenia and bone mineral density (BMD) loss in the past 6–16 years in community-dwelling older women from the Fracture RISk Brussels Epidemiological Enquiry (FRISBEE2) study.

MethodsRetrospective cohort design. Nine hundred seven community-dwelling older women constitute the baseline sample of the FRISBEE2 study. Participants had undergone an initial dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) evaluation for osteoporosis in the past 6–16 years prior to the study's commencement and were re-assessed at baseline. Baseline evaluations included EWGSOP2-defined sarcopenia (handgrip strength, appendicular lean soft tissue mass/height2, 4-m gait speed) and osteoporosis assessment (total hip BMD). Baseline BMD value of each participant was compared with their own value in the previous DXA evaluation in the past 6–16 years. A BMD loss>3.0% threshold was considered as “least significant change”. Adjusted multiple logistic regression models were used to evaluate associations between sarcopenia and BMD loss.

ResultsOut of 907 participants, 172 (19.0%) had EWGSOP2-defined probable sarcopenia, 76 (8.4%) had confirmed sarcopenia, and 630 (73.2%) experienced significant BMD loss. After adjustment for confounders, regression models showed that BMD loss>3% in the past years was associated to twofold higher odds of probable sarcopenia (i.e., low handgrip strength) [OR=2.23 (95%CI 1.36–3.66); p=0.002].

ConclusionsThe study found a clinically relevant association between the presence of sarcopenia and bone loss in the past 6 to 16 years in community-dwelling older women. A significant BMD loss should alert clinicians to the possible coexistence of sarcopenia.

Evaluar las asociaciones entre la sarcopenia definida por el grupo EWGSOP2 y la pérdida de densidad mineral ósea (DMO) en los últimos 6 a 16años en las mujeres mayores que viven en comunidad en el estudio FRISBEE 2 (Fracture RISk Brussels Epidemiological Enquiry).

MétodosDiseño de cohorte retrospectivo. Novecientas siete mujeres mayores que viven en comunidad constituyen la muestra basal del estudio FRISBEE2. Las participantes habían sido sometidas a un estudio inicial de DXA (absorciometría de rayos X de energía dual) para osteoporosis en los últimos 6 a 16 años previos al inicio del estudio, siendo reevaluadas al inicio. Dichas evaluaciones basales incluyeron sarcopenia definida por el grupo EWGSOP2 (fuerza de agarre, relación masa magra apendicular/altura2, velocidad de marcha de 4m) y evaluación osteoporótica (DMO de cadera total). Se comparó el valor basal de DMO de cada participante con su propio valor en la evaluación DXA previa de los últimos 6 a 16años. Se consideró como «cambio significativo mínimo» la pérdida de DMO>3%. Se utilizaron modelos de regresión múltiple ajustados para evaluar las asociaciones entre sarcopenia y pérdida de DMO.

ResultadosDe las 907 participantes, 172 (19%) tenían sarcopenia probable definida por el grupo EWGSOP2; 76 (8,4%), sarcopenia confirmada, y 630 (73,2%) experimentaron pérdida significativa de DMO. Tras ajustar los factores de confusión, los modelos de regresión mostraron que la pérdida de DMO >3% en los últimos años estuvo asociada a odds ratios doblemente superiores de sarcopenia probable (es decir, fuerza de agarre baja) (OR=2,23; IC95%: 1,36-3,66; p=0,002).

ConclusionesEl estudio encontró una asociación clínicamente relevante entre la presencia de sarcopenia y la pérdida ósea en los últimos 6 a 16años en las mujeres mayores que viven en comunidad. La pérdida significativa de DMO deberá alertar a los clínicos sobre la posible coexistencia de sarcopenia.

Osteoporosis is defined as a reduction of bone mass and an alteration of bone microarchitecture leading to an increased risk of fracture. The operational diagnosis of osteoporosis is established by measurement of bone mineral density (BMD) at the hip and spine using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). The World Health Organization (WHO) diagnostic criteria for osteoporosis is a BMD value that equals or is lower than 2.5 standard deviations below the average value in the reference population at one of these sites.1

Sarcopenia is a potentially reversible musculoskeletal disease, related to age (primary sarcopenia) or to other factors (secondary sarcopenia).2 It has been recently defined as “a loss of skeletal muscle mass and strength/function” and robust evidence about its association with falls, disability, and mortality is available.3 While awaiting the forthcoming operational definition from the newly formed Global Leadership Initiative on Sarcopenia (GLIS), the most widely acknowledged definition is the revised consensus on definition and diagnosis by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP2), where sarcopenia is considered “probable” in presence of a low muscle strength, “confirmed” when associated with low muscle mass,4 and “severe” if the physical performance is altered.

When exploring the association between sarcopenia and its components and osteoporosis, some evidence is available, mostly from cross-sectional studies e.g., in the SarcoPhAge study, Locquet et al., 2019 found associations among sarcopenia components and osteoporosis, indicating that community-dwelling older people with muscle muscle impairment had poorer bone health.5 Tiftik et al., 2023 found that postmenopausal women with low grip strength had a 1.6-fold higher risk of osteoporosis.6 Taniguchi et al., 2019 reported a significant association between osteoporosis and muscle mass, but not with muscle strength, in community-dwelling Japanese older women.7,8 Nevertheless, these associations were explored mostly in cross-sectional studies, and data on this association over time from large longitudinal studies are scarce or provides inconclusive findings. The association between bone mineral density (BMD) loss and sarcopenia remains poorly explored. The most recent meta-analysis by Gao et al., 2025, assessed the risk factors for sarcopenia in community settings across the life course, compiling evidence from longitudinal studies to date, and could not identify the BMD loss as one of the risk factors associated to sarcopenia.9 Given the emerging body of evidence linking the pathophysiology of osteoporosis and sarcopenia, it is crucial to unravel the long-term associations between the loss of BMD, as a dynamic process over time, and the presence of sarcopenia.

The Fracture RIsk Brussels Epidemiological Enquiry (FRISBEE 1) study is a cohort study of community-dwelling postmenopausal women initiated in Brussels (Belgium), in 2007.10 In 2021, all participants were invited to join a follow-up study, FRISBEE 2, whose baseline data, combined with a bone mineral density (BMD) assessment conducted at FRISBEE 1 inclusion, are analyzed and presented in this manuscript. The objective of this study is to assess the associations between the presence of sarcopenia in community-dwelling older women and BMD loss over the preceding years.

MethodsStudy design & participantsThis analysis and manuscript follow a retrospective cohort design. The manuscript follows the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement.11

The FRISBEE 1 cohort study was conducted in three university hospitals in Brussels, Belgium, and involved 3560 community-dwelling late post-menopausal women; the recruitment period spanned between 2007 and 2013 and the details about its evaluation have been described elsewhere.10 A first Dual-energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA) examination was performed during the FRISBEE 1 recruitment period.10 Thereafter, the participants were surveyed annually by telephone interview, until the end of 2023.

In 2021, a new follow-up study, the FRISBEE 2 study was developped: all the remaining 2322 participants from FRISBEE 1 were contacted and invited to participate, with no additional inclusion criteria apart of being eligible and consent to participate. Exclusion criteria consisted of (i) severe cognitive impairment (e.g., responses available only by family members), (ii) institutionalization/nursing home residents, (iii) severe comorbidities that would have prevented DXA examination and physical performance tests, (iv) having recently been bedridden (at least 3–4 weeks) due to a severe acute condition, which could influence DXA evaluation of body composition and BMD, (v) severe concomitant disease and short life expectancy, and (vi) refusal to participate.

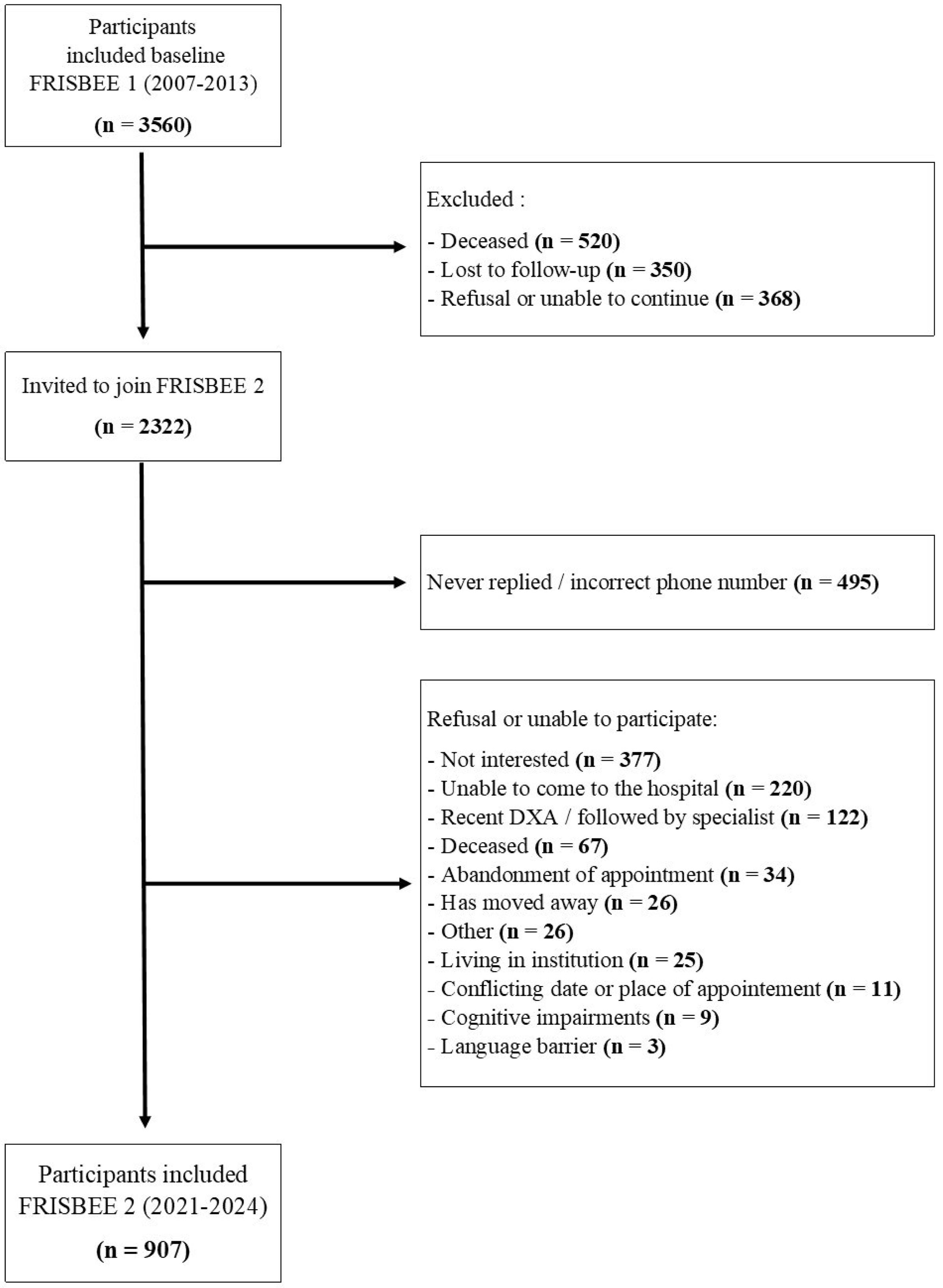

Out of the invited 2322 potential participants, 907 accepted the invitation for the new follow-up, the FRISBEE 2 study, whose the recruitment period spanned between September 2021 and January 2024. The baseline data of FRISBEE 2, combined with the initial value of the BMD from the previous osteoporosis assessment 6 to 16 years before baseline, were analyzed and presented in this manuscript (Fig. 1).

Sarcopenia components assessmentSarcopenia components were measured once, at FRISBEE 2 recruitment period (2021–2024, T2), which is considered the baseline of this retrospective cohort study.

Sarcopenia components were assessed according to the EWGSOP2 criteria, where a low handgrip strength is considered probable sarcopenia; a low handgrip strength and low muscle mass are considered confirmed sarcopenia; and the presence of low physical performance indicates severe sarcopenia.4

Muscle strength, muscle mass and physical performance were measured following the most updated recommendations.12 Handgrip strength (kg) was assessed using a Jamar® hydraulic dynamometer (Performance Health, Cedarburg, WI, USA). Strength was measured three times for both hands and the highest value was retained (Southampton protocol).13 Whole body DXA was used to measure the appendicular lean soft tissue mass (ALM), which was divided by height squared as ALMi.14 The 4-m gait speed test was assessed as part of the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB)15: participants completed a 4-meter walk, and the best performance from two timed trials was retained for analysis.

Sarcopenia was assessed with a cutoff of (i) <16kg for handgrip strength, (ii) <5.5kg/m2 for ALMi, and (iii) a 4-m gait speed test ≤0.8m/s.4

Outcome variablesAccording to the EWGSOP2 criteria, three dichotomous variables related to sarcopenia were created, (i) a variable for probable sarcopenia, taking the value 1 when handgrip strength<16kg, and 0 otherwise, (ii) a variable for confirmed sarcopenia, taking the value 1 when handgrip strength<16kg and ALMi<5.5kg/m2, and 0 otherwise, and (iii) a variable for severe sarcopenia, taking the value 1 when handgrip strength<16kg, ALMi<5.5kg/m2, and gait speed≤0.8m/s, and 0 otherwise.

Bone mineral density assessmentBMD was measured by DXA (Hologic System, Marlborough, MA, USA). BMD was measured twice, i.e., two DXA examinations were conducted for each participant:

- •

The first DXA examination was administered during the FRISBEE 1 recruitment period (2007–2013, T1).

- •

The second DXA examination was administered at FRISBEE 2 recruitment period (2021–2024, T2), which is considered the baseline of this retrospective cohort study.

Total hip BMD (TH-BMD) was the site of choice for BMD assessment. The rationale for the choice of TH-BMD was because it is optimal for defining osteoporosis by WHO standards as it is less prone to artifacts than lumbar spine BMD. Additionally, TH-BMD is considered to be more precise than femoral neck BMD, which can be influenced by positioning during DXA.16 As such, only TH-BMD was considered for the purpose of this analysis and manuscript, and the terms TH-BMD and BMD are used interchangeably in the text.

BMD loss and its least significant change thresholdDifferences in BMD between the first and the second DXA were computed as mean annual absolute difference (mg/cm2/year), i.e., the BMD value (mg/cm2) of the second evaluation (T2, baseline) was deducted from the BMD value of the first evaluation (T1), and then divided by follow-up duration (years).

A dichotomized variable for BMD change was used in the analysis. A threshold value of BMD loss>3.0% was retained as the “least significant change” (LSC), to be considered when comparing two DXA scans of the same individual.17 Therefore, based on the total difference in BMD value between T1 and T2, two groups were categorized: a first group included the participants who gained BMD, grouped with those with a BMD loss≤3.0% of their initial BMD in T1. The second group included subjects with BMD loss greater than 3.0%.

As the FRISBEE 1 and FRISBEE 2 recruitment periods spanned during several years, and the participants were not recalled in the FRISBEE 1 inclusion order, the time between the two DXA examinations of each of the participants may differ widely.

Falls and fractures assessmentThe number of self-reported falls in the past 12 months was collected during FRISBEE 2 inclusion interviews, at baseline. Reported fractures before FRISBEE 2 baseline were available, as they had been collected during each annual follow-up from 2007 to 2023 as part of the previous FRISBEE 1 study; all fractures had to be validated by written radiological and/or surgical reports. Detailed methodology is available elsewhere.18 Fragility fractures were categorized according to Major Osteoporotic Fractures (MOF, clinical spine, wrist, proximal humerus and hip) versus non-MOF (all other types of fractures).10

Other variablesA sedentary lifestyle was defined as declaring having only sedentary activities (reading, watching TV), i.e. the lowest activity level evaluated according to the 6-level scale, adapted from the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) World Health Organization score.10 Participants were considered treated for osteoporosis if they declared being under treatment with osteoporosis-specific drugs at FRISBEE 2 baseline.

Statistical analysisAll statistical analyses were performed with Stata 17.0 SE (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Descriptive analyses were performed as mean±standard deviation or median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were described as percentages. Comparisons were performed with Student's t-test, Wilcoxon rank test, Chi-square, or Fisher's exact test according to the variables’ characteristics.

Variables that were associated (p<0.3) with confirmed sarcopenia in univariate analysis were included in a stepwise backward selection procedure. Consequent multiple logistic regression models were used to evaluate associations between EWGSOP-defined sarcopenia and the presence of BMD loss in the past years, adjusting for potential confounding factors.

Model adjustments were evaluated with Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, and their classification capacities were assessed. A linktest was used to evaluate the correct specification. The colinarity between covariates was assessed by calculating the Variation Inflation Factor (VIF). All statistical tests were two-tailed and p<0.05 was considered significant.

Ethical aspectsWritten informed consent was obtained from each participant. The Local Ethics Committee approved the study protocol (CHU Brugmann reference number: CE CHUB 2021/91). This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, its further amendments (Fortaleza 2013), and the Good Clinical Practice guidelines (GCPs). Data were collected and treated according to the European Union General Data Protection Regulation 2016/679.

ResultsThe detailed flowchart of the study is depicted in Fig. 1. Nine-hundred seven community-dwelling older women were included in the FRISBEE 2 study and their data have been used for this analysis and manuscript.

Table 1 describes the participants’ characteristics in the FRISBEE 2 study at baseline. The median age was 77 (IQR 75–81) years and the median BMI was 26.2 (IQR 23.0–29.6)kg/m2. Out of 907 older women, 172 (19.0%) had EWGSOP2-defined probable sarcopenia, 76 (8.4%) had confirmed sarcopenia, and severe sarcopenia was present in 43 (4.8%) participants at baseline.

Description of the participants’ characteristics in the FRISBEE 2 study at baseline (n=907).

| Characteristic | n | Total population | Participants with EWGSOP2 “confirmed” sarcopenia76 (8.4%) | Participants without EWGSOP2 “confirmed” sarcopenia825 (91.6%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 907 | 77 (75–81) | 80 (77–85) | 77 (75–81) | 0.000 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 906 | 26.2 (23.0–29.6) | 23.4 (21.0–26.1) | 26.5 (23.1–30.1) | 0.000 |

| Probable sarcopenia/handgrip strength<16kg | 904 | 172 (19.0%) | 76 (100%) | 96 (11.6%) | 0.000 |

| ALMi<5.5kg/m2 | 904 | 348 (38.5%) | 76 (100%) | 270 (32.7%) | 0.000 |

| 4-m gait speed test≤0.8m/s | 903 | 329 (36.4%) | 43 (57.3%) | 283 (34.4%) | 0.000 |

| Severe sarcopenia | 899 | 43 (4.8%) | 43 (57.3%) | 0 (0%) | – |

| Osteoporosis (based on T-score BMD)a | 907 | 219 (24.2%) | 27 (35.5%) | 189 (22.9%) | 0.014 |

| Current osteoporosis treatment | 905 | 54 (6.0%) | 6 (7.9%) | 48 (5.8%) | 0.469 |

| Calcium and/or Vitamin D supplements intake | 904 | 788 (87.2%) | 64 (85.3%) | 720 (87.5%) | 0.592 |

| Current menopausal hormone therapy | 907 | 73 (8.1%) | 5 (6.6%) | 68 (8.2%) | 0.611 |

| Early non-substituted menopause | 907 | 33 (3.6%) | 4 (5.3%) | 29 (3.5%) | 0.438 |

| Corticoids intake (past 12 months) | 901 | 37 (4.1%) | 5 (6.7%) | 32 (3.9%) | 0.250 |

| Actively smoking | 903 | 50 (5.5%) | 2 (2.6%) | 48 (5.8%) | 0.428 |

| Excessive alcohol intake (≥3 units/day) | 905 | 37 (4.1%) | 1 (1.3%) | 36 (4.4%) | 0.358 |

| Sedentary lifestyle | 906 | 85 (9.4%) | 15 (19.7%) | 68 (8.3%) | 0.001 |

| Comorbidities | 787 | 113 (14.4%) | 16 (23.9%) | 97 (13.6%) | 0.022 |

| Annual BMD change in the past 11 years (mg/cm2/year) | 861 | 6.12±6.25 | 7.77±6.02 | 5.93±6.22 | 0.018 |

| BMD loss>3% in the past years (T1–T2)b | 861 | 630 (73.2%) | 65 (85.5%) | 606 (73.5%) | 0.021 |

| History on fracture in the past years (T1–T2) | 907 | ||||

| MOFb | 132 (14.6%) | 16 (21.1%) | 114 (13.8%) | 0.194 | |

| Non-MOF | 96 (10.6%) | 6 (7.9%) | 90 (10.9%) | ||

| One or more falls in the past 12 months | 903 | 298 (33.0%) | 30 (40.0%) | 266 (32.3%) | 0.176 |

| Two or more falls in the past 12 months | 903 | 134 (14.8%) | 11 (14.7%) | 121 (14.7%) | 0.993 |

| Follow-up duration (years) | 907 | 11 (10–13) | 11 (10–13) | 11 (10–13) | 0.126 |

ALMi: appendicular lean soft tissue mass index: appendicular lean soft tissue mass/height2 (kg/m2); BMD: bone mineral density at the total hip; EWGSOP2: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis of sarcopenia; EWGSOP2-defined probable sarcopenia: handgrip strength<16kg: EWGSOP2-defined confirmed sarcopenia: handgrip strength<16kg and ALMi<5.5kg/m2; EWGSOP2-defined severe sarcopenia: handgrip strength<16kg and ALMi<5.5kg/m2 and gait speed≤0.8m/s (Cruz-Jentoft et al., 2019); MOF: Major Osteoporotic Fracture: clinical spine, wrist, proximal humerus and hip.

The total hip BMD from two DXA scans within each same participant was compared, i.e., the BMD at baseline (T2) was compared with the BMD measured in a previous study, 6–16 years before (T1), to obtain the difference T1–T2. A total hip bone mineral density (BMD) loss>3.0% was considered the “least significant change” threshold (Tothill et al., 2007), and was used to categorize the study sample in two groups.

As expected, participants with confirmed sarcopenia were older, had a lower BMI, higher prevalence of osteoporosis, were more likely to present comorbidities, and reported a sedentary lifestyle more frequently than those participants without sarcopenia; those differences were statistically significant.

The time duration between the second DXA examination at FRISBEE 2 study baseline (T2) and the first DXA examination (T1) ranged from 6 to 16 years and its median was 11 (IQR 10–13) years. The difference (T1–T2) in BMD could not be assessed for 46 participants that had missing data for DXA: 17 individuals had missing data in T1 and 37 individuals (of which 8 are the same) had missing data in T2 (data not shown).

Overall, the mean annual BMD difference (T1–T2) in the past years was a loss of 6.12±6.25mg/cm2/year; this average annual BMD loss was higher in participants with confirmed sarcopenia (7.77mg/cm2/year) than in those without (5.93mg/cm2/year, p=0.018). A small proportion of the participants (68, 7.9%) gained more than 3% BMD between the two DXA examinations, but the majority of the participants (630, 73.2%) had experienced a BMD loss of more than 3% between the two DXA examinations. In between, 163 (18.9%) participants were considered to have stable BMD.

Table 2 shows the crude odds ratio obtained by logistic regression, estimating the association of EWGSOP2-defined probable, confirmed, and severe sarcopenia in the FRISBEE2 study baseline (T2) with a total hip bone mineral density (BMD) loss of more than 3% in the past 6–16 years. In these univariate models, a loss of more than 3% in total hip BMD over the past 6–16 years was associated with statistically significantly increased odds of EWGSOP2-defined sarcopenia (probable, confirmed, and severe).

Crude odds ratio from the logistic regression estimating the association between EWGSOP2-defined sarcopenia and BMD loss of more than 3% in the preceding 6–16 years.

| Univariate analysis | Probable sarcopenia | Confirmed sarcopenia | Severe sarcopenia | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | n | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | n | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| BMD loss>3% in the past years (T1–T2) | 859 | 2.37 (1.49–3.76) | 0.000 | 856 | 2.07 (1.07–4.02) | 0.031 | 831 | 3.46 (1.22–9.85) | 0.02 |

BMD: bone mineral density; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; EWGSOP2: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis of sarcopenia;EWGSOP2-defined probable sarcopenia: handgrip strength<16kg; EWGSOP2-defined confirmed sarcopenia: handgrip strength<16kg and ALMi<5.5kg/m2; EWGSOP2-defined severe sarcopenia: handgrip strength<16kg, ALMi<5.5kg/m2, and gaitspeed≤0.8m/s (Cruz-Jentoft et al., 2019).

The total hip BMD from two DXA scans within each same participant was compared, i.e., the BMD at baseline (T2) was compared with the BMD measured in a previous study, 6–16 years before (T1), to obtain the difference T1–T2. A total hip bone mineral density (BMD) loss>3.0% was considered the “least significant change” threshold (Tothill et al., 2007), and was used to categorize the study sample in two groups.

.

All covariates associated with confirmed sarcopenia at a significance level of p<0.3 (Table 1) were included in the backward stepwise selection procedure. The set of retained covariates varied between models, reflecting differences in their respective contributions to the outcomes examined.

Table 3 presents the estimated odds ratios (ORs) for all covariates included in the multivariable logistic regression model. The association between probable sarcopenia and BMD loss remained statistically significant after adjusting for potential confounders. Specifically, individuals who experienced a BMD loss greater than 3% over the previous years had 2.23 times higher odds of presenting probable sarcopenia, even after controlling for age, sedentary lifestyle, comorbidities, history of major osteoporotic fracture, and follow-up duration. Each of these factors independently contributed to an increased likelihood of probable sarcopenia.

Adjusted odds ration from the logistic regression estimating the association between BMD loss and EWGSOP2-defined probable sarcopenia (n=745).

| Multivariable analysis | Probable sarcopenia | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| BMD loss>3% in the past years (T1–T2) | 2.23 (1.36–3.66) | 0.002 |

| Age (years) | 1.11 (1.06–1.16) | 0.000 |

| Sedentary lifestyle | 4.06 (2.35–7.02) | 0.000 |

| Comorbidities | 1.90 (1.14–3.17) | 0.014 |

| History of MOF | 1.73 (1.04–2.88) | 0.033 |

| Follow-up duration (years) | 1.18 (1.06–1.32) | 0.003 |

.

BMD: bone mineral density; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; MOF, Major Osteoporotic Fracture: clinical spine, wrist, proximal humerus and hip; EWGSOP2: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis of sarcopenia; EWGSOP2-defined probable sarcopenia: handgrip strength<16kg (Cruz-Jentoft et al., 2019).

The total hip BMD from two DXA scans within each same participant was compared, i.e., the BMD at baseline (T2) was compared with the BMD measured in a previous study, 6–16 years before (T1), to obtain the difference T1–T2. A total hip bone mineral density (BMD) loss>3.0% was considered the “least significant change” threshold (Tothill et al., 2007), and was used to categorize the study sample in two groups.

Table 4 shows the adjusted odds ratios from the logistic regression estimating the association between BMD loss and EWGSOP2-defined confirmed sarcopenia. After adjustment for relevant covariates, a BMD loss greater than 3% was not significantly associated with confirmed sarcopenia (p=0.358). Conversely, increasing age, a sedentary lifestyle, and the presence of comorbidities were again identified as contributing factors to a higher likelihood of confirmed sarcopenia. Notably, a higher BMI was associated with significantly lower odds (OR: 0.80; p<0.001). History of Major Osteoporotic Fractures and follow-up duration were not retained in this model.

Adjusted odds ratio from the logistic regression estimating the association between BMD loss and EWGSOP2-defined confirmed sarcopenia (n=742).

| Multiple model | Confirmed sarcopenia | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| BMD loss>3% in the past years (T1–T2) | 1.41 (0.68–2.93) | 0.358 |

| Age (years) | 1.10 (1.04–1.16) | 0.002 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 0.80 (0.73–0.86) | 0.000 |

| Sedentary lifestyle | 3.66 (1.63–8.22) | 0.002 |

| Comorbidities | 2.30 (1.14–4.65) | 0.021 |

.

BMD: bone mineral density; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; EWGSOP2: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis of sarcopenia; EWGSOP2-defined confirmed sarcopenia: handgrip strength<16kg and ALMi<5.5kg/m2 (Cruz-Jentoft et al., 2019).

The total hip BMD from two DXA scans within each same participant was compared, i.e., the BMD at baseline (T2) was compared with the BMD measured in a previous study, 6–16 years before (T1), to obtain the difference T1–T2. A total hip bone mineral density (BMD) loss>3.0% was considered the “least significant change” threshold (Tothill et al., 2007), and was used to categorize the study sample in two groups.

Analysis for severe sarcopenia was not feasible due to the limited sample size of participants with this condition in the study sample (n=43).

DiscussionThe study assessed the associations between sarcopenia according to the EWGSOP2 and changes in the total hip BMD in the past 6 to 16 years, in a large population of community-dwelling older women. The presence of probable sarcopenia, i.e., low handgrip strength, was associated to a clinically significant BMD loss in the past years, also after adjustement for confounders. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study assessing the association between the dynamic process of the loss of bone mineral density in a long-term backwards timeline, and the presence of sarcopenia in community-dwelling older women.

Our results are in line with the findings about the cross-sectional association between the components of bone health, muscle health, and sarcopenia found in community-dwelling older people in the baseline of the SarcoPhAge study.5 In a longitudinal prospective study with a 5-year follow-up, the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA) and the National Institute for Longevity Sciences-Longitudinal Study of Aging (NILS-LSA) showed that bone loss and muscle loss were lost in parallel (co-occurred), and that the loss was higher in women than in men.19

Several considerations in relation to the findings and the adjusting variables should be discussed. The analysis used BMI as one of the counfounding factors, and a higher BMI was associated with significantly lower odds of confirmed sarcopenia. Lee et al., 2016, found an association between sarcopenia and osteoporosis, which was no longer significant after adjustment for body fat.20 These partially contradictory findings might be partly attributed to the inherent limitations of DXA in accurately assessing muscle mass, as it encompasses both water and fibrotic tissue alongside lean mass. The influence of BMI and body composition on musculoskeletal health remains controversial and futher longitudinal studies may be needed to clarify this association.

The study found an independent association between a self-reported sedentary lifestyle and confirmed sarcopenia, which is coherent with the evidence reporting the benefits of physical activity and reducing sedentary lifestyle. Physical activity has been found to play a key role in determining the relationship between low BMD and sarcopenia.20 Other authors found higher levels of physical activity in healthy women compared with osteoporotic women, and higher physical activity levels have shown to be associated with an increased cortical strength.21 Globally, there is robust evidence from longitudinal studies showing an inverse relationship between physical activity and bone loss.22

The presence of comorbidities was retained in the model for probable and confirmed sarcopenia, highlighting their association, which may reflect the presence and coexistance of both primary and secondary sarcopenia in the study population. Finally, the length of follow-up was also included in the statistical model, and it was found that the association was valid independently of the length of the follow-up and the timeframe between the two DXA examinations. This may be interesting to interpret the findings, showing robustness despite the large variety of duration in the timeframe between the DXA examinations. Yet the findings could not be generalized outside a 6–16 years follow-up duration.

Bone and muscle interact through a complex bidirectional crosstalk, with an emerging evidence linking the pathophysiological mechanisms of both sarcopenia and osteoporosis.23 Osteosarcopenia is a recently described geriatric syndrome, characterized by the concomitant presence of sarcopenia and osteoporosis. A recent meta-analysis showed that osteosarcopenia significantly increased the risk of falls, fracture, and mortality.24 A greater prevalence of osteosarcopenia in females compared to males, primarily attributed to postmenopausal hormonal changes affecting both bone and muscle metabolisms and to the tendency for women to have lower weight and BMD than men of the same age has been described.24 While the epidemiology of osteosarcopenia provides valuable information, the biggest potential of this newly described geriatric syndrome may lay in the possibility to develop synergistic therapeutic interventions, involving physical exercise and physical medicine and rehabilitation notably.25,26

Three strengths of our study could be highlighted. First, the study counts with the highest methodological quality, including a large sample size and a rigorous osteoporosis and sarcopenia assessment, with data obtained from systematic annual interviews, including validation of all past fractures in the radiological reports, over more than a decade. To authors’ knowledge, this is one of the largest studies including a rigourous osteoporosis and sarcopenia assessment available to date. Second, the study is highly innovative, as to the best of our knowledge, the relationship between BMD change over a decade and an objective evaluation of muscle strength and mass in a large group of postmenopausal women has not been reported before. Finally, the study is timely, as the study provides valuable data about the longitudinal relationship between the two diseases and may help to lay the grounds to unravel the crosstalk between bone and muscle.

Five limitations should be acknowledged. First, the retrospective study design does not allow to establish cause-effects relationships, but associations. Second, there is a selection bias, as the study was conducted only in those participants who were able to attend the evaluation centers on site, potentially leading to underrepresentation of frail women or those who had died in the previous years before study baseline. Moreover, the study mostly considered older white European women, which may limit the generability of the findings, and thus not be valid for men or other populations.27 Third, no validated assessment tools for the nutritional status and physical activity evaluation were used, which could also be considered as a limitation of the study. Fourth, inflammatory markers were not included, although they could be key confounders in the decline of muscle function and bone mass. Given the current evidence linking low-grade chronic inflammation to osteosarcopenia and the high potential of biomarkers, further studies incorporating inflammatory markers are warranted to better understand and treat musculoskeletal system during the aging process.28,29 Finally, there was an heterogeneity in the time between the two DXA examinations, which may vary from 6 to 16 years among participants, with 75% of the sample ranging from 10 to 13 years. Thus, the binary variable for BMD loss used in the analysis may have grouped older women with different profiles and characteristics, as their losing rate may vary widely.

In summary, we observed a two-fold higher odds for probable sarcopenia in the community-dwelling older women who lost more than 3% of their total hip BMD over the past years. Our findings also suggest that the systematic implementation of the inexpensive and easy-to-perform handgrip strength assessment into osteoporosis and comprehensive geriatric evaluations in clinical practice, particularly in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation or Geriatric Medicine, could serve as a supportive tool in osteoporosis assessment. It may help identify individuals who have experienced a clinically relevant BMD loss in recent years and are therefore at increased risk of osteoporosis and fractures. Future studies should examine concomitant changes in sarcopenia and osteoporosis in a prospective manner, identifying modifications in their components over time to provide a more accurate perspective of the relationship between bone and muscle.

Ethics approvalEthical approval for this study was obtained from the Comité d’éthique du CHU Brugmann (Approval Number: CE 2021/91).

Informed consentWritten informed consent was obtained for anonymized patient information to be published in this article.

FundingsThe study was supported by the Fondation Brugmann, CHU Brugmann, IRIS-Recherche, and Fondation Vésale.

Conflict of interestJean-Jacques Body reports financial support provided by UCB Inc. Dolores Sanchez-Rodriguez reports personal speaker fees from Nutricia, unrelated to this work. The other authors declare that they have no competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this manuscript.

The authors would like to thank all the women participating in the FRISBEE cohort since 2007 and the nuclear medicine teams of CHU Brugmann and CHU Saint-Pierre who carried out the DXA examinations and offered their full logistical support.