To evaluate the effectiveness of practical ultrasound workshops for the acquisition and consolidation of conceptual learning about the basic physics and semiology of ultrasonography aimed at third-year medical school students doing the physical examination module of their studies.

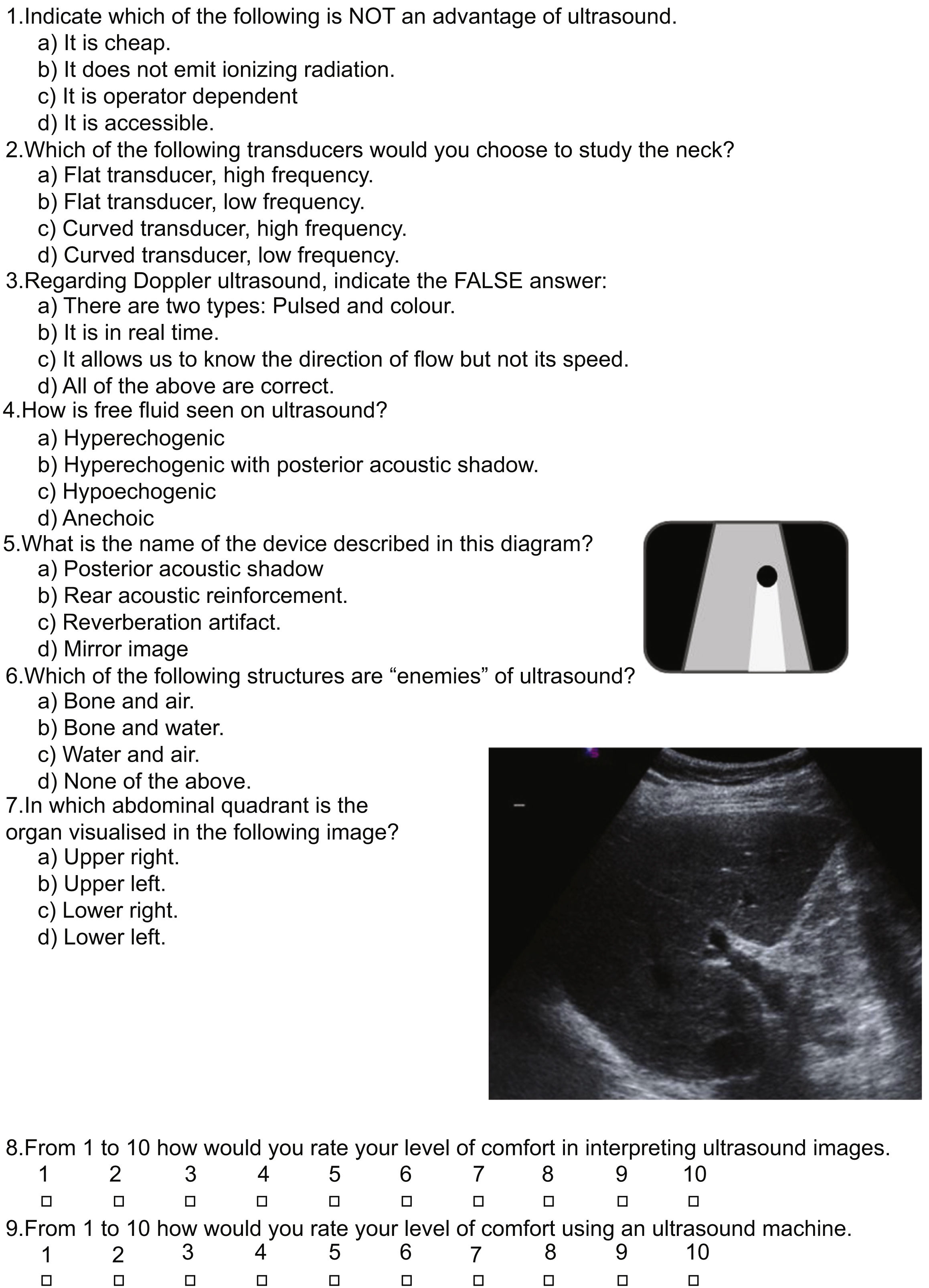

Material and methodsWe carried out practical ultrasound workshops with two groups of 177 and 175 students in two consecutive academic years. All students had taken a class in basic radiology in the previous year. Students examined each other with ultrasonography under instructors’ supervision in a 2-h session. Before and after the workshop, students did a seven-question multiple-choice test about basic semiology and answered two questions evaluating their degree of confidence in interpreting ultrasonographic images and handling the ultrasound scanner on a scale from 1 to 10.

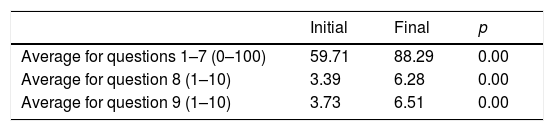

ResultsNo significant differences were found between the scores obtained in the two groups. Overall, the mean score on the multiple-choice test improved from 59.71% on the initial assessment to 88.29% on the post-workshop assessment (p<0.01). Confidence in interpreting images improved from 3.39/10 to 6.28/10 (p<0.01), and confidence in handling the equipment improved from 3.73/10 to 6.51/10 (p<0.01).

ConclusionPractical workshops were useful for learning basic concepts about ultrasound imaging, allowing students to significantly improve their scores on the multiple-choice test. Students had a low level of confidence in their ability to interpret ultrasound images and handle the equipment before starting the workshop, but their confidence improved significantly after completing the workshop.

Evaluar la efectividad de los talleres prácticos de ecografía en la adquisición y afianzamiento de conceptos de física y semiología ecográfica básica, dirigidos a estudiantes del módulo de exploración física en el tercer año del grado de Medicina.

Material y métodosSe impartieron talleres prácticos de ecografía a dos grupos de 177 y 175 alumnos durante dos cursos académicos consecutivos. Todos ellos habían cursado una asignatura de radiología básica durante el curso académico anterior. Los estudiantes realizaron exploraciones ecográficas entre ellos, bajo supervisión, en una sesión práctica de 2 horas de duración. Se realizó un examen antes de empezar el taller y, nuevamente, al concluir este. El examen constaba de siete preguntas de elección múltiple sobre semiología básica y de dos preguntas que evaluaban del 1 al 10 el grado de confianza al interpretar imágenes ecográficas y al manejar un ecógrafo.

ResultadosNo se encontraron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en las puntaciones obtenidas entre ambos cursos (p >0,05). En conjunto, la puntuación media del cuestionario inicial fue del 59,71%, que mejoró de forma significativa hasta el 88,29% tras el taller (p<0,01). La confianza inicial en la interpretación de imágenes y en el manejo del ecógrafo fue de 3,39/10 y 3,73/10, respectivamente. Después del taller mejoró significativamente hasta los 6,28/10 y 6,51/10, respectivamente (p<0,01).

ConclusiónLos talleres prácticos demostraron ser útiles en el aprendizaje de conceptos básicos de ecográfica, logrando una mejoría significativa en la puntuación final del cuestionario. Los estudiantes partieron con un bajo nivel de confianza en la interpretación de imágenes y manejo de un ecógrafo, el cual también mejoró significativamente.

The use of ultrasound is integrated into the daily clinical practice of many medical specialties aside from Radiology, such as Primary Care, Internal Medicine, Rheumatology, Paediatrics and Intensive Medicine. In addition, ultrasound training for these specialties is gradually beginning to be implemented in the Spanish specialty training pathway (MIR) for some of them.1–7 In this sense, the extension of the use of ultrasound in clinical practice has implied an increase in its use in medical schools worldwide.8,9

Ros Mendoza et al. establish that the competences in radiology that a general practitioner should have would include knowledge of different imaging methods with their indications, semiology and radiological anatomy, as well as basic pathology.10

Some studies have shown that the introduction of radiology from the earliest medicine courses favours, in the long term, a greater interest and a better perception of the field of radiology,11 as well as the valuing of its clinical importance and an improvement in the acquisition of knowledge.12

On the other hand, according to the classic concept of the “learning pyramid”, students retain approximately 75–90% of the concepts through practical activities or through teaching others, while this percentage falls to 5–10% when their time is spent exclusively attending lectures.13 However, several authors have questioned the results of this theory given its methodological errors.14 Along the same lines, Feilchenfeld et al. question the benefits of ultrasound as a learning method for anatomy or other concepts, since empirical evidence demonstrating this is still scarce.9

The objective of this work is, therefore, to evaluate the usefulness of practical ultrasound workshops in the learning and consolidation of basic knowledge about ultrasound technique and semiology in a population of third year medical students who have previously acquired these competences through lectures.

Material and methodsDevelopment of the practical workshopsThe study was conducted during the first term of the 2018–2019 and 2019–2020 academic courses, with samples of 177 and 175 third year medical students, respectively. In each course, the students were divided into eight different groups of about 20–25 people. Each group participated in a 2-h practical ultrasound workshop. These workshops were integrated into a practical physical examination model.

The contents of the workshop were the same for all the groups. The first part consisted in a theoretical explanation of about 5min on basic ultrasound concepts, fundamentally the physical bases and the basic semiology. During the previous academic year, i.e. during their second year of medicine, all the students had attended a basic radiology course on technique, semiology and radiological anatomy, so the contents of the theoretical part of the workshops were already known

Next, the students had to practice ultrasound management in pairs, by performing abdominal and cervical ultrasound scans on each other. All workshops were conducted under the supervision of two junior doctors (in MIR training) from the Radiodiagnosis specialty.

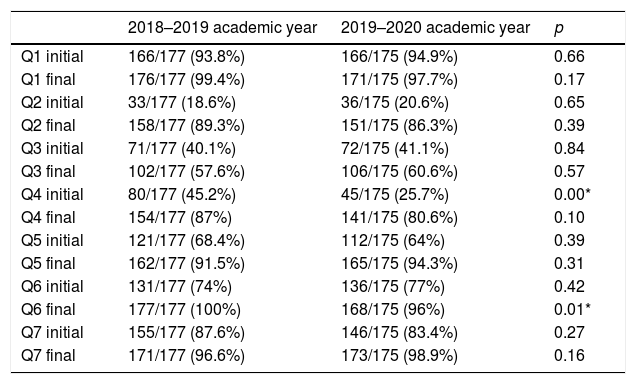

Written evaluation of the workshopsFor the evaluation of these workshops, a nine-question questionnaire was conducted at the beginning, before the theoretical explanation, in order to evaluate the students’ baseline knowledge. The first seven questions were multiple choice questions with four options, one of them correct. They were about theoretical concepts of physical bases and ultrasound semiology, two of them with an associated image. The remaining two questions were a subjective assessment of 1–10 of the level of personal confidence when interpreting ultrasound images and when handling an ultrasound scanner, respectively (Fig. 1). Students were informed beforehand that the test results had no influence on their final grade in the subject.

Once the practical part was finished, at the end of the workshop, the students answered the questions again. To enable the tests to be paired up, each student provided their university card number.

Statistical analysisTo check if there were significant differences between the results obtained in each academic year, Student's t test was used for independent samples and Pearson's χ2 test was used based on the variable studied. To analyse the differences between the results of the questionnaires before and after the workshop, Student's t test was used for paired samples, and a McNemar test.

The IBM SPSS Statistics 20 programme was used in the statistical analysis. Two-tailed p values were taken, and p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

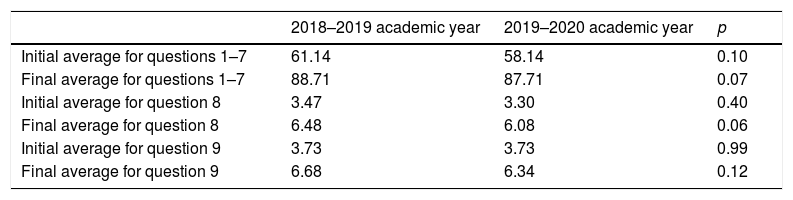

ResultsAnalysis of the differences between the coursesThe average of the exam results obtained in each academic year was compared. Although the results of the students in the 2018–2019 academic year were slightly higher than those obtained by the students in the 2019–2020 academic year these differences were not considered significant (p>0.05) in the statistical analysis (Table 1).

Results obtained by the students of each academic year, both in the initial and final evaluation.a

| 2018–2019 academic year | 2019–2020 academic year | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial average for questions 1–7 | 61.14 | 58.14 | 0.10 |

| Final average for questions 1–7 | 88.71 | 87.71 | 0.07 |

| Initial average for question 8 | 3.47 | 3.30 | 0.40 |

| Final average for question 8 | 6.48 | 6.08 | 0.06 |

| Initial average for question 9 | 3.73 | 3.73 | 0.99 |

| Final average for question 9 | 6.68 | 6.34 | 0.12 |

The averages of questions 1–7 refers to the multiple-choice theory questions, expressed on a scale of 0–100. The averages of questions 8 and 9 correspond to the questions on subjective assessment of personal confidence, scored from 1 to 10. The p value in Student's t test for paired samples was not significant.

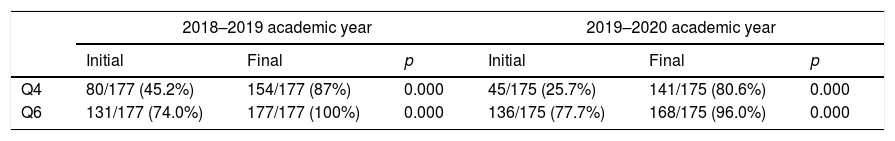

When considering multiple choice questions individually, no significant differences were found, except for the fourth question in the evaluation before the workshop (45% correct in the 2018–2019 academic year vs. 25.7% correct in the 2019–2020 academic year; p=0.00) and in the sixth question after the workshop (100% correct in the 2018–2019 academic year vs. 94.3% correct in the 2019–2020 academic year; p=0.01) (Table 2).

Comparison of the proportion of correct answers obtained in the different multiple-choice questions in each academic year, both in the initial and final evaluation.a

| 2018–2019 academic year | 2019–2020 academic year | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 initial | 166/177 (93.8%) | 166/175 (94.9%) | 0.66 |

| Q1 final | 176/177 (99.4%) | 171/175 (97.7%) | 0.17 |

| Q2 initial | 33/177 (18.6%) | 36/175 (20.6%) | 0.65 |

| Q2 final | 158/177 (89.3%) | 151/175 (86.3%) | 0.39 |

| Q3 initial | 71/177 (40.1%) | 72/175 (41.1%) | 0.84 |

| Q3 final | 102/177 (57.6%) | 106/175 (60.6%) | 0.57 |

| Q4 initial | 80/177 (45.2%) | 45/175 (25.7%) | 0.00* |

| Q4 final | 154/177 (87%) | 141/175 (80.6%) | 0.10 |

| Q5 initial | 121/177 (68.4%) | 112/175 (64%) | 0.39 |

| Q5 final | 162/177 (91.5%) | 165/175 (94.3%) | 0.31 |

| Q6 initial | 131/177 (74%) | 136/175 (77%) | 0.42 |

| Q6 final | 177/177 (100%) | 168/175 (96%) | 0.01* |

| Q7 initial | 155/177 (87.6%) | 146/175 (83.4%) | 0.27 |

| Q7 final | 171/177 (96.6%) | 173/175 (98.9%) | 0.16 |

Given the overall results obtained, it was decided to perform the paired analysis considering both populations together.

Analysis of the differences between the results before and after the workshopIn the multiple-choice questions (questions 1–7), the average score for the initial results was 59.71/100, which improved to 88.29/100 in the final questionnaire, the p value of Student's t test for paired samples being significant (p<0.05). The same trend was observed in questions about the assessment of personal confidence when interpreting ultrasound images (question 8) and when handling an ultrasound scanner (question 9). In these questions, students went from 3.39 and 3.73 points on average initially out of a total of 10 points, to 6.28 and 6.51 points on average, respectively, with statistically significant differences (p<0.05) (Table 3).

Comparison of the average obtained in the different multiple choice questions.a

| Initial | Final | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average for questions 1–7 (0–100) | 59.71 | 88.29 | 0.00 |

| Average for question 8 (1–10) | 3.39 | 6.28 | 0.00 |

| Average for question 9 (1–10) | 3.73 | 6.51 | 0.00 |

The difference in the average score in the theoretical questions (questions 1–7) are expressed on a scale from 0 to 100, while the questions on confidence assessment (questions 8 and 9) are expressed on a scale from 1 to 10. In all cases the p value obtained in Student's t test for paired samples was significant.

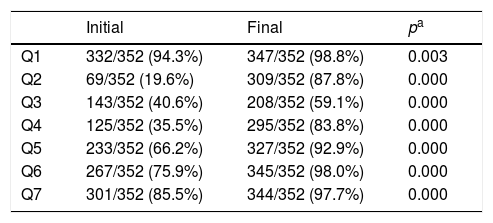

Looking at the multiple-choice questions individually, the McNemar test was significant in all of them (p<0.05), obtaining significant improvements in the final evaluation (Table 4).

Comparison of the proportion of correct answers obtained in the different multiple-choice questions in each academic year, both in the initial and final evaluations.

| Initial | Final | pa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | 332/352 (94.3%) | 347/352 (98.8%) | 0.003 |

| Q2 | 69/352 (19.6%) | 309/352 (87.8%) | 0.000 |

| Q3 | 143/352 (40.6%) | 208/352 (59.1%) | 0.000 |

| Q4 | 125/352 (35.5%) | 295/352 (83.8%) | 0.000 |

| Q5 | 233/352 (66.2%) | 327/352 (92.9%) | 0.000 |

| Q6 | 267/352 (75.9%) | 345/352 (98.0%) | 0.000 |

| Q7 | 301/352 (85.5%) | 344/352 (97.7%) | 0.000 |

Having found significant differences in the comparison of the results of the two academic years for the fourth question before the workshop and for the sixth question after the workshop, it was decided to conduct an additional analysis of these questions in each course separately, and significant improvements were also found (p<0.05) (Table 5).

Analysis by subgroups of the questions in which statistically significant differences were found.a

| 2018–2019 academic year | 2019–2020 academic year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Final | p | Initial | Final | p | |

| Q4 | 80/177 (45.2%) | 154/177 (87%) | 0.000 | 45/175 (25.7%) | 141/175 (80.6%) | 0.000 |

| Q6 | 131/177 (74.0%) | 177/177 (100%) | 0.000 | 136/175 (77.7%) | 168/175 (96.0%) | 0.000 |

The results obtained indicate that practical ultrasound workshops can be a good teaching method to strengthen basic concepts of physics and basic ultrasound semiology. The improvement in the results was significant for all the questions, even considering that the initial results in the multiple-choice questions were satisfactory given the theoretical basis that the students had when they completed the basic radiology course, since they reached a global average of over 50% correct answers. In fact, the only question that less than 100 out of 352 students answered correctly in the initial assessment was the second one, in which they were asked about the characteristics of the ultrasound probes (frequency, depth reached), a concept that probably exceeded the objectives of this course. However, in the final evaluation, the results obtained in this question were in line with the rest of the questions, with more than 80% of answers correct. The only exception was the third question, which reached 59% correct answers after completing the workshop. We believe that the reason may be in the wording of the question, since it includes an option of “all of the above are correct”, which can be considered a confounding factor in multiple choice exams.

Similar results were obtained in the subjective personal assessment questions. The students started from a low level of confidence of 3.39/10 for the interpretation of ultrasound images and 3.73/10 for ultrasound management. Despite the significant improvement, they remained relatively low, with an average of 6.28/10 and 6.51/10, respectively. One might ask whether this is due to the technique itself and if similar results would be found in workshops focused on learning the other radiological techniques.

These results are also in line with other published works. For example, in 2014 García de Casasola et al. evaluated the capabilities of 12 medical students in the acquisition of ultrasound planes and in the detection of relevant pathological findings in real patients after 15h of theoretical and practical training, and obtained satisfactory results.15 In another publication from this same working group, good results were obtained in the identification of ultrasound planes in healthy volunteers after a course taught by the medical students themselves.16

One of the study's advantages was the sample size, which had a population of 352 medical students from two different academic years. The fact that significant differences in the questionnaire results between the different academic years were not found supports the reproducibility of this type of teaching. In addition, the fact that they had completed a previous course on basic radiology allows the impact of the practical part of the workshop to be assessed, since the theoretical concepts had already been acquired in lectures. This fact is indicated in the work done by Kraft et al. in 2018, in which they assessed the impact of the introduction to radiology during the first year of medicine. There, the students’ greater interest in radiology and valuing of its impact on patient management were highlighted as positive points, with the need for greater prior knowledge of anatomy being a negative point.17 Lastly, we consider as a positive point the inclusion of questions assessing perceived personal confidence, which gives an extra focus to the work and which could be included in future work on the evaluation of other teaching methods for different radiology techniques, such as the simple X-ray.

As for disadvantages, it is worth noting the low number of questions in the questionnaire, with a total of nine. Although the overall analysis is good and no incongruous results have been found, a larger number of questions could minimise the possible biases caused by the form of the questions or enable differentiation between concepts acquired in the theoretical classes and new concepts introduced in the workshops. Another possible bias that could affect this work would be the Hawthorne effect within the subjective assessment questions, although there was an attempt to minimise this by communicating this questionnaire's lack of repercussion on the final mark to the students. Finally, it is worth noting the fact that only one teaching methodology has been evaluated. In future work, the option of dividing the sample into different groups and comparing different teaching methods in each could be considered.

Authorship- 1.

Responsible for the integrity of the study: APN, JCPV.

- 2.

Study conception: APN, PMO, JCPV.

- 3.

Study design: APN, PMO, ACIR, ISA.

- 4.

Data acquisition: APN, PMO, ACIR, ISA.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: APN, PMO, ACIR, ISA, JCPV.

- 6.

Statistical processing: APN, PMO, ISA.

- 7.

Literature search: APN, PMO, ACIR, JCPV.

- 8.

Drafting of the article: APN, PMO.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: APN, JCPV.

- 10.

Approval of the final version: APN, PMO, ACIR, ISA, JCPV.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Paternain Nuin A, Malmierca Ordoqui P, Igual Rouilleault AC, Soriano Aguadero I, Pueyo Villoslada JC. Talleres prácticos de ecografía para estudiantes de Medicina como método de enseñanza de conceptos básicos de semiología ecográfica. Radiología. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rx.2019.12.003