Image acquisition involves the use of static magnetic fields, field gradients and radiofrequency waves. These elements make the MRI a different modality. More and more centers work with 3.0 T equipment that present higher risks for the patient, compared to those of 1.5 T.

Therefore, there is a need for updating for radiology staff that allows them to understand the risks and reduce them, since serious and even fatal incidents can occur.

The objective of this work is to present a review and update of the risks to which patients are subjected during the performance of a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study.

El uso de campos magnéticos estáticos, gradientes de campo y ondas de radiofrecuencia suponen un reto de seguridad diferente a otras modalidades de imagen. Cada vez más centros trabajan con equipos de 3,0 T que presentan mayores riesgos para el paciente frente a los de 1,5 T.

Hay una necesidad de actualización para el personal de radiología que le permita entender los riesgos y disminuirlos, pues pueden producirse incidentes graves e incluso mortales.

El objetivo de este trabajo es presentar una revisión y actualización de los riesgos a los que se ven sometidos los pacientes durante la realización de un estudio de resonancia magnética (RM).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a diagnostic modality the clinical indications of which have increased in recent years, mainly thanks to technological advances.1 Compared to the 1.5 T scanners, the 3.0 T machines provide better image quality because the increased magnetic field improves the signal-to-noise ratio and this increased signal can be transformed into greater detail (increased spatial resolution) and faster acquisition (increased temporal resolution).2–4

Disadvantages include increased susceptibility to motion and flux, exposure to stronger static magnetic fields, increased tissue heating and increased noise.3,4 While MRI-related incidents are numerous, serious incidents are rare.5

With 3.0 T scanners, some safety concepts change compared to scanners with a weaker magnetic field. Some items previously considered safe on a 1.5 T scanner may not be safe on a 3.0 T scanner.6 Staff involved in performing MRI need to know about all situations requiring special attention which could compromise patient safety.1

The aim of this paper is to present the MRI risk map. For this purpose, MRI will be divided into three parts according to time: pre-procedure, during the procedure and post-procedure.

Pre-procedureBefore performing an MRI scan, the physician and radiologist should assess the risk-benefit ratio, whether the results will change the patient's management and whether they are sure it cannot be replaced by other diagnostic information.

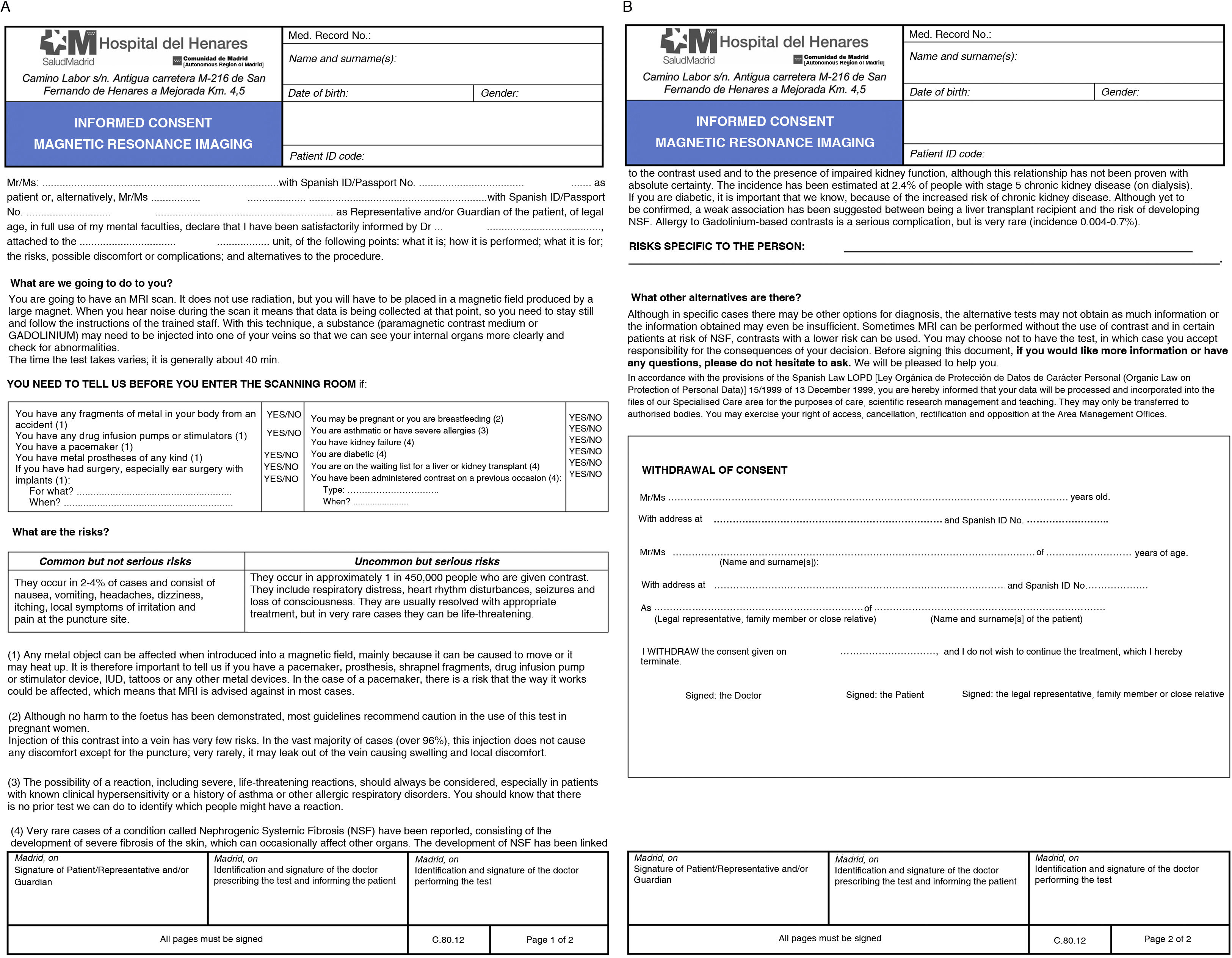

Signed written informed consent is not required in most studies, but it is necessary to explain to the patient the main risks and benefits of the test. As an example, Fig. 1 shows the informed consent form from our centre with a safety questionnaire.

The different population subgroups and possible scenarios that can be anticipated prior to screening are discussed below.

Paediatric patientAll safety criteria for the adult population should be applied to this age group, which is particularly vulnerable due to their anxiety, immaturity and limited communication skills. Anxiety is minimised by the presence of a family member in the examination room, to whom basic instructions should have been given beforehand. The study can be performed under sedation or anaesthesia with the same degree of safety as it would be done in other locations in the hospital.1 The greater speed with which scans can be obtained with 3.0 T compared to 1.5 T machines makes them a good choice for reducing sedation time.3

Pregnant patientNo harmful effects on the pregnant woman or the foetus have been demonstrated following non-contrast MRI.7,8 Testing in the first trimester of pregnancy has not shown any higher risk than in other trimesters.8 There is also no evidence of teratogenic effects or acoustic damage to the foetus.2 It is advisable to make sure that the test needs to be done at that time, that it cannot be delayed to the postpartum period and that it cannot be substituted by another examination such as ultrasound. Specific informed consent forms should be available for these patients. In pregnant women, 1.5 T scanners should be used, given the limited number of published studies on risk to the mother and foetus when using 3.0 T machines.9 Recent studies show no evidence of increased risk to the foetus in intrauterine MRI with 3.0 T scanners compared to 1.5 T.10

Patient with claustrophobiaThe physical space where the MRI is performed and the limitation of movement means there are patients who cannot tolerate being put into the machine or cannot complete the test because of claustrophobia. Series have been published in which 25% have experienced moderate or severe anxiety, 13.7% panic attacks and scans interrupted in 4% due to anxiety.11,12 The requesting physician and the radiology staff need to commit to providing a more extensive explanation to help reduce patient anxiety levels.13 The use of open MRI is not always the solution, due to limitations in the type and quality of studies which can be performed. The diameter of the gantry has been increased in the new scanners to reduce the feeling of claustrophobia.14 Sedation/anaesthesia may be an option where adequate staff and MRI-compatible anaesthetic equipment are available. Other centres opt for psychological therapy or the use of anxiolytics prior to the procedure.15 Each centre should have a protocol which assesses the best course of action for each patient.16

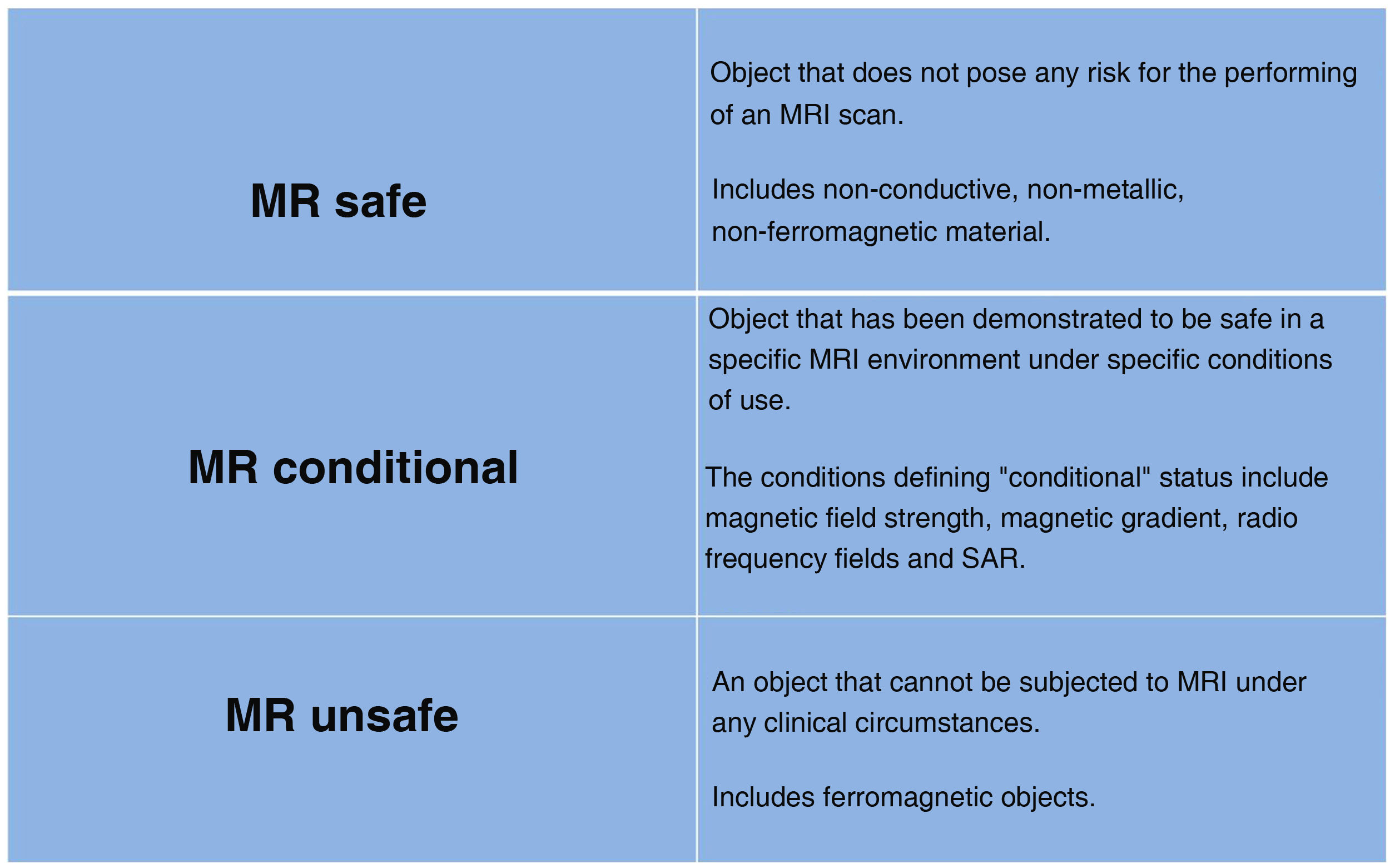

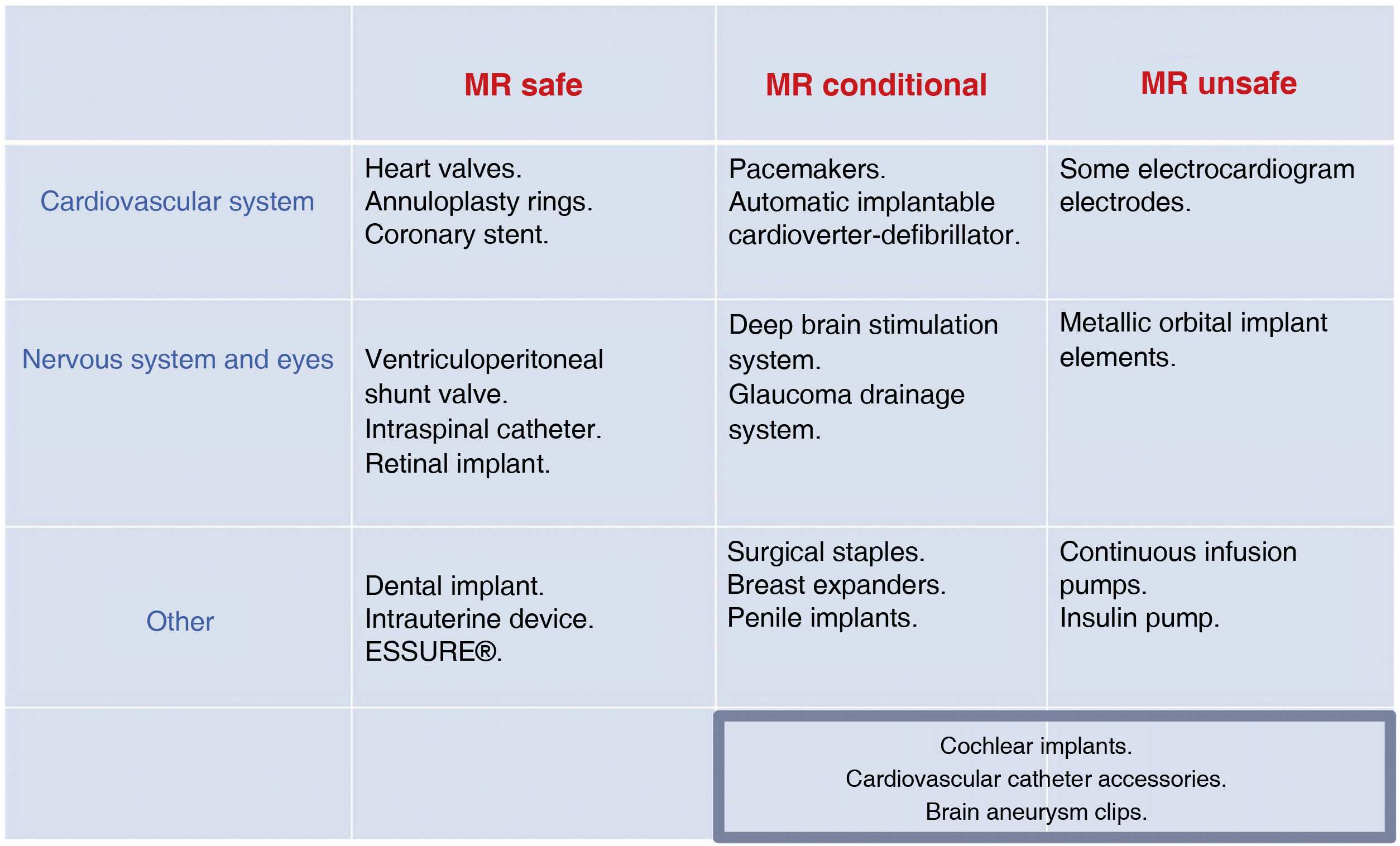

Patients with metal implants and implanted devicesA large number of MRI scans can now be performed on patients with implanted metal elements or devices. There are implants considered safe in 1.5 T scanners which are not approved, or are not known to be safe for 3.0 T. As many as 1800 objects have been tested at 1.5 T and just over 600 at 3.0 T.17 Devices should be evaluated by the manufacturer and labelled for MRI compatibility with different icons (Fig. 2). There are two online references on MRI safety (mrsafety.com and www.radiology.pitt.edu/mrrc-mri-safety.html),18,19 which can be consulted for device compatibility.

The International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection (ICNIRP) establishes limits for certain parameters to work with in MRI to ensure patient safety20: static magnetic field; gradient strength; radiofrequency power deposition (Specific Absorption Rate [SAR]); and noise level. In the case of patients with metal implants and devices, the particularly critical parameters are:

- -

Strong static magnetic fields (B0): cause an object to move, rotate or accelerate towards the magnet (missile effect).

- -

Magnetic field gradients: can cause electrical currents and neuromuscular stimulation.

- -

Radio-frequency fields: induce heat and cause burns. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and ICNIRP limit the temperature increase to less than 1 °C with a whole body SAR of 4.0 W/kg, within a maximum scan time of 30 min.21 Increased SAR leads to dilation of blood vessels, increased sweating, and the risk of burns. Therefore, extra caution should be exercised in patients with fever, and blankets, plaster casts and clothing that increase body temperature should be avoided. It should be ensured that the ventilation system is operating correctly, high SAR sequences should be interspersed with lower SAR sequences, and the use of 1.5 T rather than 3.0 T scanners should be considered in specific cases.22,23

When a patient has a device, the specific test/patient risk/benefit should be assessed, reliable information on the specific device, implantation time and manufacturer's recommendations should be obtained, the device should be removed prior to MRI, if possible, and informed consent, which reflects the type of device and possible complications, should be obtained. Tests may be performed with devices labelled “MR safe” or “MR conditional”, provided that their performance parameters are in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations.

Having a previous MRI is no guarantee of safety, as the equipment, anatomical area or type of sequence may have been changed and complications could arise which did not occur in the previous scan.23 Devices are considered as “unsafe” if labelled as such or when no information on the type or manufacturer's considerations is available.

If an element has a magnetic susceptibility different from that of the surrounding tissues, it alters the homogeneity of the local magnetic field and causes a loss of signal.22,24 To decrease metal artefacts24–26 we can decrease the magnetic field (less artefact occurs in 1.5 T scanners); increase the bandwidth; reduce the slice thickness, increase the gradient amplitude and increase the matrix, which results in a decrease in the signal-to-noise ratio; spin echo (SE) sequences produce less susceptibility artefact than gradient echo (GRE) sequences because they use spin-rephasing pulse sequences of 1.800 s, which are not included in the GRE; use fast spin echo (FSE) sequences instead of GRE, short T inversion recovery (STIR) instead of fat saturation sequences or fast spoiled gradient echo instead of steady-state free precession (SSFP); or use specific sequences such as metal artefact reduction sequence (MARS).22

Cardiovascular devicesCardiac pacing devices: pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillatorsIt is estimated that 50%–75% of patients with cardiac pacing devices will require at least one MRI in their lifetime.27 There are published consensus documents28–30 containing the safety conditions.31 Most manufacturers provide information on the devices, including on those labelled as MR conditional: the conditions of use; the region to be studied; the acquisition parameters; and the specific activation of the device before and after MRI. All device components should be from the same manufacturer, who may also advise delaying MRI for six weeks after implantation.32 Many cardiac pacing devices have been approved for 1.5 T scanners, but there are few studies in 3.0 T fields. Devices not labelled by the manufacturer as MR conditional or MR safe should be considered unsafe.31

In the case of a pacemaker-dependent patient with an MR conditional device and no implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) function, it should be programmed in DOO/VOO mode, which allows adaptation to the haemodynamic needs of the patient (demand mode).28,32,33

In self-pacing patients, reprogramming is in DDI/VVI mode, allowing the patient to have a fully functional pacing device.28

In ICD, anti-tachycardia therapies should be deactivated,28 as the currents generated when introduced into the magnetic field can be interpreted as tachyarrhythmias.32 MRI is considered contraindicated in patients with epicardial leads, abandoned electrodes and temporary pacemakers. Wireless devices such as loop recording devices (subcutaneous implantable Holter) are considered safe.28–30

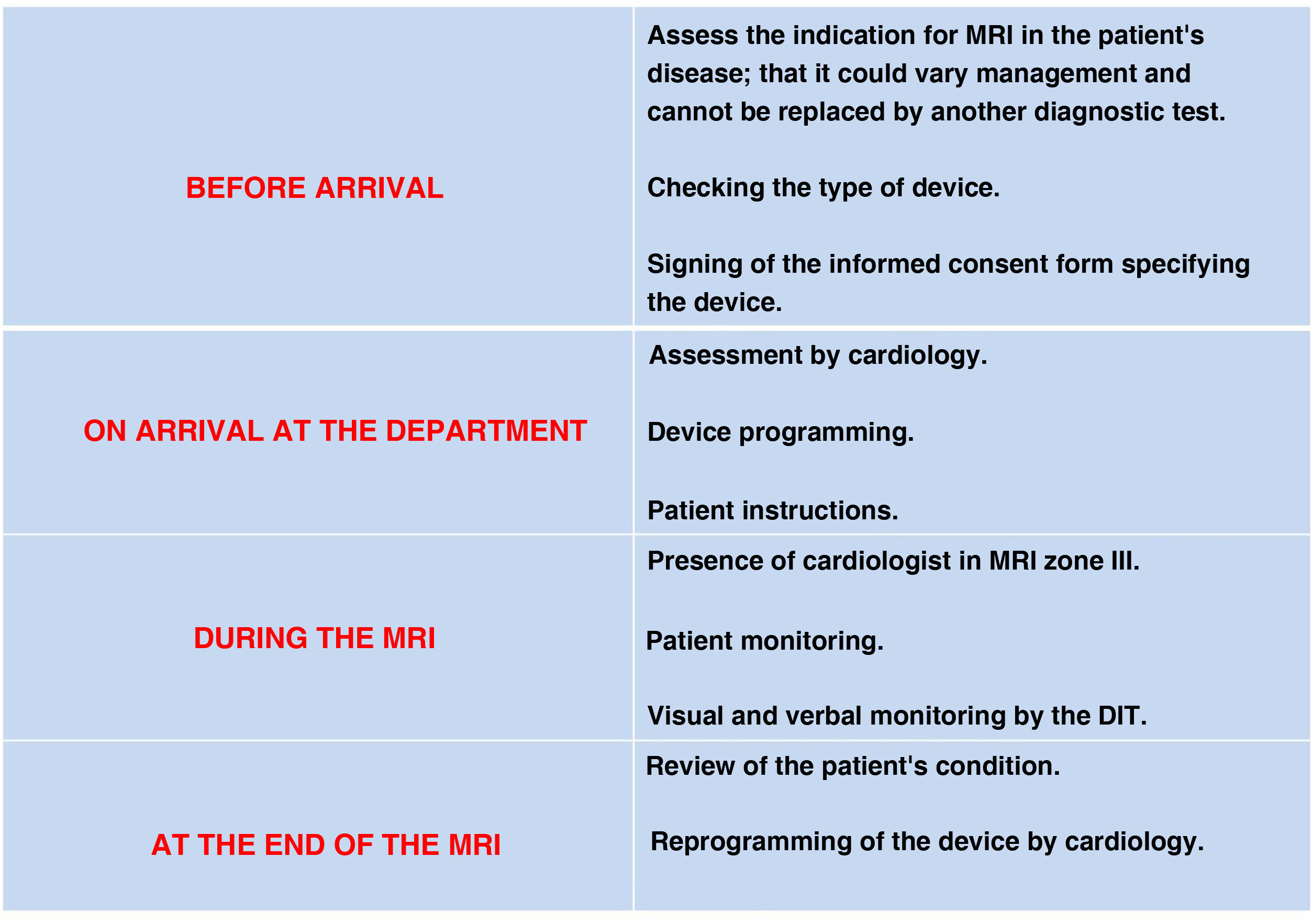

Each centre should have a protocol agreed with the cardiology department for the personalised assessment of each patient, with a prior examination to assess the device and the patient's dependence on pacing, and a subsequent examination to confirm correct functioning and perform the corresponding reprogramming. Both proceedings should be recorded. Fig. 3 shows a flowchart for the patient with a cardiac pacing device.29

Prosthetic valves, annuloplasty rings and coronary stentsThese are MR safe in 1.5 fields regardless of the time since implantation,34,35 including drug-eluting stents.36 In 3 T fields, the management of prosthetic valves and mechanical valved conduits should follow the manufacturer's instructions.28

Aortic stent graftMost are non-ferromagnetic or weakly ferromagnetic and, with the exception of a few specific types, can be introduced into fields up to 3.0 T.35,37

Monitoring and circulatory support catheters (Swan-Ganz and continuous output catheter)They do not have ferromagnetic elements, but incorporate conductive material which can cause burns and impair their function.38 They are not safe in MRI.28

Vena cava filtersIt is safe to perform 1.5 or 3.0 T MRI even immediately after placement.35 With the weakly ferromagnetic filters it is recommended to wait six weeks before introducing into 1.5 T fields.39

Neurological devicesIntracranial aneurysm clipsSome may become displaced. Others which are non-ferromagnetic can be introduced into 1.5 and 3.0 T fields.40 It is necessary to consult the manufacturer's information, and to avoid ferromagnetic clips, which were discontinued in 1997.21

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt valvesIf they are considered compatible by the manufacturer, they are compatible up to 3.0 T fields, and from the time of implantation. Some makers recommend that the proper functioning of the valve should be checked after the test.18

Intraspinal catheterThey have been shown to be safe in fields up to 1.5 T. The patient should be told to inform staff in the event of heating and neurostimulation. As a precaution the catheter should be emptied of medication (most contain morphine with the risk of overdose if a malfunction occurs) and deactivated during MRI.33

Ear, nose and throat devicesCochlear implantsOlder implants are contraindicated because they contain metal and internal magnets which made them MR unsafe.33

Some of the strategies used when MRI is necessary are the removal of the magnet from the internal component of the cochlear implant and the use of splints and head bandaging to prevent displacement of the magnet. Models are available with MR compatibility at 1.5 and 3.0 T without the need to remove the magnet or use bandaging during the examination. It is essential to know which model is implanted beforehand in order to ensure the safest practice in each case.

Contraceptive devicesESSURE® and intrauterine devices (IUD) are MR safe at 1.5 and 3.0 T.41

Dental implantsThe biggest problem is the artefact they produce when they are in the field being studied. An overview of the safety of the most common medical devices is provided in Fig. 4.

Tattoos and make-upTattoos do not contraindicate MRI, but caution should be exercised, especially with very dark inks.42 We should inform the patient of the risk, and place cold compresses or saline bags over the tattoo to absorb any heat release.

Make-up should be removed before the MRI is performed.

Jewellery and body piercingThese elements should be removed. They can burn and become displaced, and any displacement will be greater for scanners with a larger field such as 3.0 T. If they cannot be removed, they should be wrapped with gauze, tape or other similar material in such a way as to prevent contact with the skin.

Patients with known or suspected metallic foreign bodiesThese patients should be pre-assessed for the possibility of movement and heating of the foreign body. Plain X-ray is the recommended technique for detecting foreign bodies, as its sensitivity enables identification of any metallic object with a mass large enough to present a hazard on MRI.22

ClothingSome underwear or sportswear can contain metallic microfibres with an antimicrobial effect.43 Patients should undress completely, including underwear, and be provided with a hospital gown for the MRI scan.

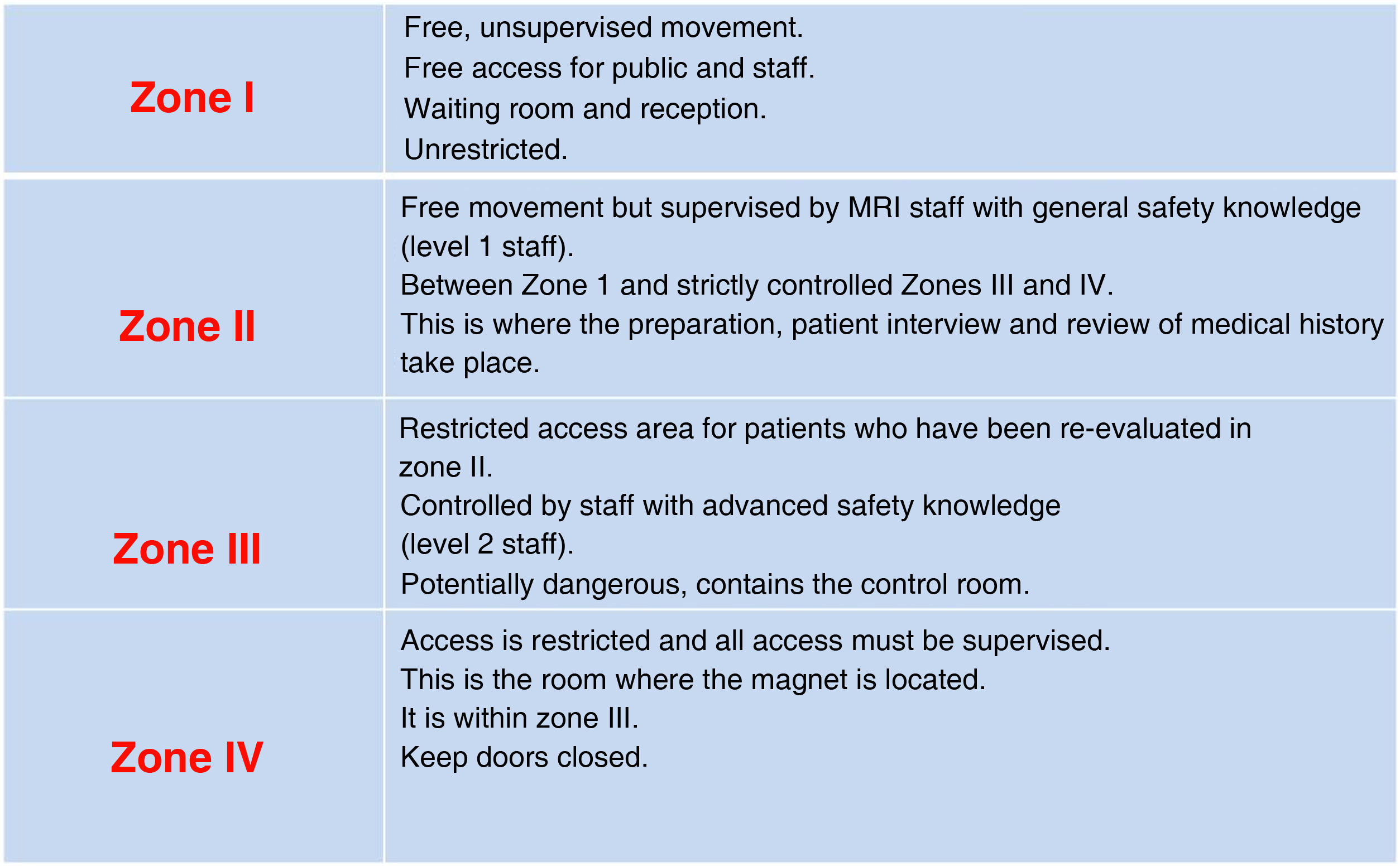

During the procedureThe patient will move through four zones with different access and restrictions (Fig. 5). Staff will give them the appropriate instructions according to the area they are in.1,22,44 The patient should be asked about possible contraindications and again provided with information about the characteristics of the test, which will increase their cooperation.

The radiologist is the person who should indicate the use of contrast. Those used are gadolinium-based, which have very high safety ranges.1,45 The standard dose of intravenous gadolinium administration is 0.1 mmol/kg body weight, which is equivalent to 0.2 ml/kg when the contrast is 0.5 molar. T1 relaxation times of soft tissues generally increase with higher magnetic field strength and the relative T1 shortening effects of contrasts, such as gadolinium, remain unchanged, leading to more pronounced contrast enhancement of gadolinium-based contrast agents against a background of tissues with longer T1 relaxation time. This effect increases the chances of potentially halving the contrast dose at 3.0 T compared to 1.5 T.46–48 There are no safety differences in relation to the use of contrast in scanners of different field strength.

Adverse reactions to gadoliniumSuch reactions are unusual and vary from 0.004% to 0.7% depending on the series.49 Most are mild (hives or urticaria) and rarely associated with bronchospasm. Possible reactions include coldness, heat or pain at the injection site, nausea with or without vomiting, headache, paraesthesia, dizziness and itching.50 Life-threatening anaphylaxis or non-allergic anaphylactic reactions are extremely rare (0.001%–0.01%).

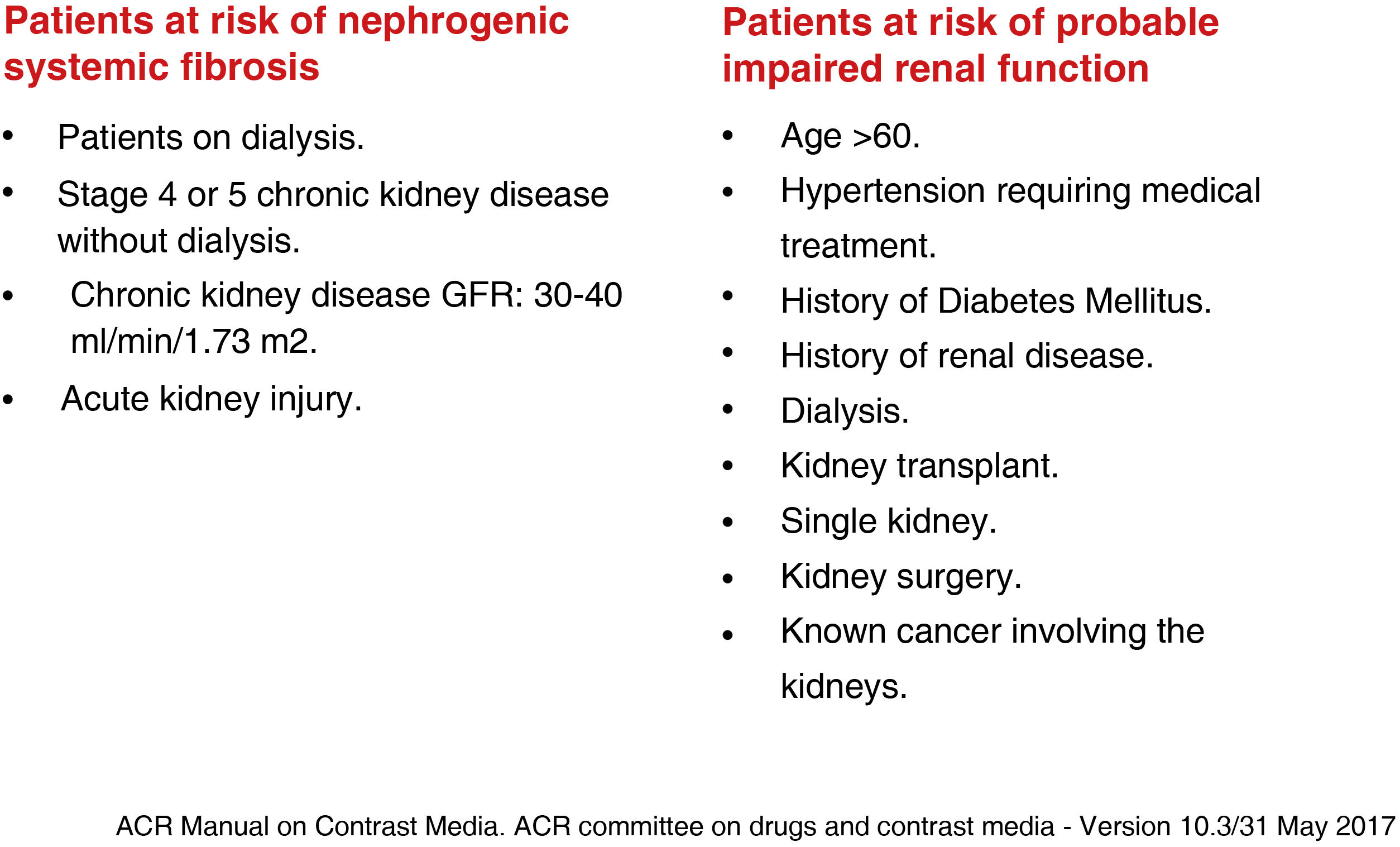

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosisDescribed in 2000 by Cowper et al.51 This is a systemic, fibrotic disease affecting the skin and internal organs, similar to scleroderma, which occurs within three months of contrast injection. It can be fatal, due to respiratory failure and limiting mobility.49–51 There is no treatment and the diagnosis is established by skin biopsy.49,50,52 It occurs in patients with severe renal impairment, with an estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 ml/min/1.73 m52 (Fig. 6). Most cases reported have been with the use of linear agents, particularly gadodiamide, which is associated with an estimated incidence of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) of 3%–18% in patients with severe renal impairment.50,51 Renal function does not need to be determined when macrocyclic agents are administered. The use of gadolinium should be avoided in children under one year of age because of their renal immaturity unless the benefit to the patient outweighs the risk.1,29 The development of nephrogenic fibrosis is very rare in this population.53 There have been few studies on the safety of gadolinium in pregnancy.54 It is known to cross into the foetus and persist in the amniotic fluid, so administration should be limited as far as possible.4,50,55

Brain depositsSeveral studies suggest that linear contrast agents (gadobenic acid, gadodiamide, gadopentetic acid and gadoversetamide) cause the formation of larger brain gadolinium deposits than macrocyclic contrasts.50,56 They are identified as regions of hyperintensity in the deep nuclei of the brain on non-contrast T1-weighted images. No neurological symptoms have been reported and the clinical significance is unknown. It occurs independent of renal function.4,49,57 The Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios (AEMPS) [Spanish Agency for Medicines and Medical Devices] has discontinued the intravenous use of all high-risk gadolinium-based contrast agents (gadodiamide and gadopentetate dimeglumine) and the marketing authorisation holder has withdrawn gadoversetamide from the European market.50,58 However, it authorises the use of high-risk linear agents (dimeglumine gadopentate) for arthrography and intermediate-risk agents (dimeglumine gadobenate and gadoxetate disodium) for hepatobiliary studies.49,50

BurnsThey are difficult to predict and although rare, can be severe and fatal. They occur because the human body is conductive and burns occur on metal-to-skin contact and because circuits are created that release energy if they form a loop. A cable coiled on the patient has a higher risk of burning than if uncoiled. Proper positioning of the patient and the use of pads are important. Wires and elongated objects can act as antennae, and produce current near their tips. Any such items measuring more than 26 cm in a 1.5 T scanner or more than 13 cm in a 3.0 T scanner are the most at risk of producing heat.59,60 The risk of burns is highest and most severe in 3.0 T scanners because the doubling of field strength quadruples the SAR,1 but they can occur in machines of any field strength.42 Extreme caution should be exercised in sedated or anaesthetised patients who are unable to report pain.61

NoiseNoise affects patients and workers, resulting in difficulties in verbal communication, increased anxiety, temporary hearing loss, and even permanent hearing impairment.62 The most susceptible patients are psychiatric patients, older adults and children, due to their auditory immaturity.63,64 The main cause of the noise is the gradient coils. The 3.0 T scanners produce noise that can double that of 1.5 T scanners and be as loud as 130 dB, so the patient should be provided with disposable earplugs or headphones.1 The FDA has set a maximum decibel level that MRI scanners should produce at 140 dB.23 New machines, 3.0 T in particular, have noise abatement techniques.65

Peripheral neurostimulationElectric currents can cause pain in extremities (arms and legs), where the magnetic field is changing most rapidly.66 The degree of involvement varies according to the individual. It is necessary to monitor the patient, asking about the presence or absence of pain.

QuenchQuenching is the controlled release or accidental leakage of helium from its circuit, which results in loss of the magnetic field.1,8 The low temperature of the helium can cause burns and expansion of the gas as it evaporates can displace oxygen and lead to asphyxiation.1 To prevent this, staff must be trained and follow the manufacturer's instructions. Installation of the scanner has to include a dedicated venting system to allow rapid expulsion of the gas to the outside.

Post-procedureAt the end of the MRI study, the technical staff should ask patients about any new abnormal sensations they may have and carry out a check of their condition.

Wound care for burnsSome patients are not aware of the burns during the scan and only report blisters, redness or pain 24 h later. A visual check of the patient should be made before they leave Zone III and a first dressing applied if they have any burns.

Contrasts and breastfeedingBeing water soluble, less than 0.004% is excreted in human milk and less than 1% of the contrast is absorbed by the infant, so it is considered safe to continue breastfeeding.45,49,50 Nevertheless, the patient should be informed so that she can decide whether or not to stop breastfeeding for the 24 h after contrast administration.1,49

Contrast extravasationAs much less contrast is used and the injection rate is much slower than with iodinated contrast, extravasation is very rare. Treatment is local, with elevation of the limb, application of cold and anti-inflammatory ointments.

Reprogramming of pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillatorsThese patients should be re-assessed by cardiology and their devices reprogrammed.

Blood tests after gadolinium injectionThe results of blood or urine tests may be altered in the first 24 h after injection of gadolinium, and for up to 48 h in patients with impaired renal function. It is recommended that blood or urine be collected prior to the administration of a contrast agent. In patients with impaired renal function (eGFR < 45 ml/min/1.73 m2) blood samples should be delayed as long as possible after administration of a contrast agent. The effects of the contrast agent on the analyses vary depending on the analytical method used.50

Preparation of the reportThe report should make specific mention of the scanner used, sequences, peculiarities of the patient and any devices they may have, type and amount of contrast and any incidents that may have occurred.67

Cleaning of the machineThe risk of acquired infections in a diagnostic radiology department is low.68 Surface cleaning should be performed between each patient, with more rigorous cleaning protocols at regular intervals.69 The introduction of metallic elements during cleaning which could cause the “missile effect” must be avoided and staff must be specifically trained.

Reporting of incidentsAny incidents that may occur during the process have to be reported through the established channels at each centre, not in an attempt to apportion blame, but with the aim of learning from mistakes and avoiding their repetition.

ConclusionsMRI is very safe compared to other imaging techniques. However, it is not without risks, which are increased in 3.0 T scanners (particularly acoustic noise and burns). It is vital that the radiologist and the technical staff performing the examination are aware of the risks to which the patient is exposed at each stage of the process.

- 1.

Responsible for study integrity: PF, JM, LG, LG and PQ.

- 2.

Study conception: PF.

- 3.

Study design: PF.

- 4.

Data acquisition: PF.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: N/A

- 6.

Statistical processing: N/A

- 7.

Literature search: PF.

- 8.

Drafting of the manuscript: PF.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually sig-nificant contributions: JM, LG, LG and PQ.

- 10.

Approval of the final version: JM, LG, LG and PQ.

This work was not subsidised and nor was any financial aid received from any public or private institution.

Conflicts of interestWe declare that there are no conflicts of interest with this work.