Obtaining CCTA images with optimal injection location such as the arm or leg is important to avoid the artifacts caused by the CM. This study compares the computed tomography (CT) numbers and visualization scores of the three-dimensional (3D) images of the lumens of the blood vessels in the arm or leg during cardiac computed tomography angiography (CCTA) in neonatal and infant patients.

Patients or Materials and MethodsBetween January 2017 and January 2020, 253 consecutive patients were considered for inclusion. We used the estimated propensity scores as a function of the demographic data, including age, body weight, and injection location (right or left side) in the arm (n = 58) and leg (n = 58) of neonatal and infant patients. We compared the mean CT numbers of the pulmonary artery, ascending aorta, and left superior vena cava; contrast–noise ratios (CNR); and visualization scores between the arm and leg as the injection locations.

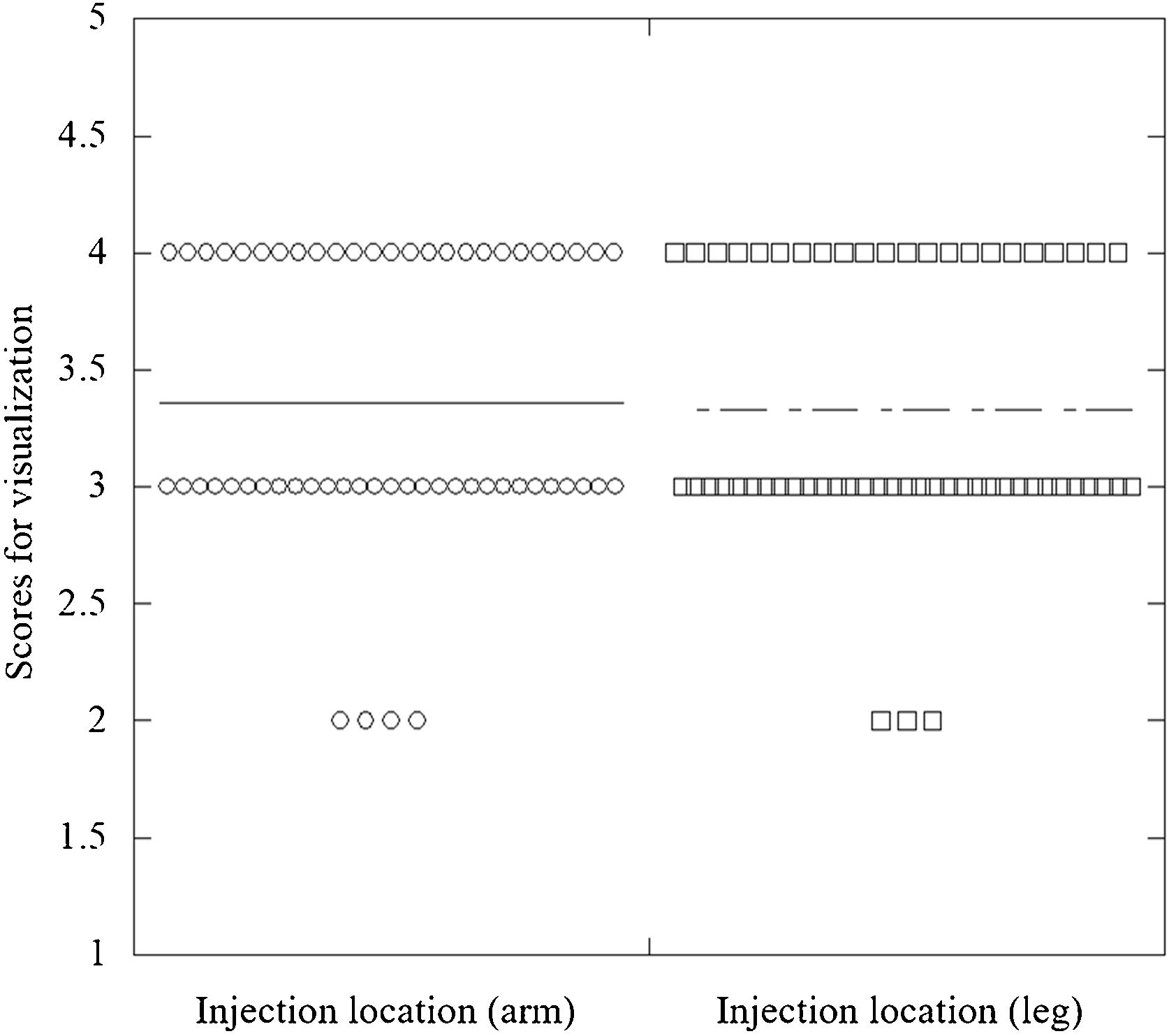

ResultsThe mean CT numbers during CCTA for the arm and leg were 479.4 and 461.3 HU in the ascending aorta, 464.2 and 448.1 HU in the pulmonary artery, and 232.8 and 220.1 HU in the left superior vena cava, respectively. The mean image noise (SD) and CNR values, respectively, were 38.9 HU and 12.1 for the arm as the injection location and 39.1 HU and 12.3 for the leg as the injection location. The median visualization scores of volume rendering of the 3D images were 3.0 and 3.0 for the arm and leg injection sites, respectively. There were no significant differences in the mean CT numbers of the ascending aorta, pulmonary artery, and left superior vena cava; SD value; CNR; and visualization scores between the arm and leg injection locations.

ConclusionsThe CT numbers of the lumen of the blood vessel and visualization scores of the 3D images of the arm and leg injection locations are equal during CCTA in neonatal and infant patients with congenital heart disease.

En la obtención de imágenes de angiografía por cardiotomografía (ACT) es importante escoger una ubicación adecuada para inyectar el medio de contraste (p. ej., el brazo o la pierna) a fin de evitar la formación de artefactos que este provoca. En este estudio se comparan los valores de tomografía computarizada (TC) y las puntuaciones de visualización de las imágenes tridimensionales (3D) de los lúmenes de los vasos sanguíneos del brazo y la pierna durante la ACT en pacientes neonatos y lactantes.

Pacientes o materiales y métodosEntre los meses de enero de 2017 y enero de 2020 se evaluaron 253 pacientes de forma consecutiva para determinar su inclusión en el estudio. Se utilizaron las puntuaciones de propensión estimadas en función de los datos demográficos, incluidos la edad, el peso corporal y la ubicación de la inyección (lado derecho o izquierdo) en el brazo (n = 58) y la pierna (n = 58) de los pacientes neonatos y lactantes. A continuación, se compararon los valores medios de TC de la arteria pulmonar, la aorta ascendente y la vena cava superior izquierda; las relaciones contraste-ruido (RCR); y las puntuaciones de visualización del brazo y la pierna como lugares de inyección.

ResultadosLos valores medios de TC durante la ACT para el brazo y la pierna fueron de 479,4 y 461,3 UH en la aorta ascendente, de 464,2 y 448,1 UH en la arteria pulmonar y de 232,8 y 220,1 UH en la vena cava superior izquierda, respectivamente. Los valores medios de ruido de la imagen (DE) y de RCR fueron, respectivamente, de 38,9 y 12,1 UH para el brazo y de 39,1 y 12,3 UH para la pierna. Las puntuaciones medias de visualización de la representación del volumen de las imágenes 3D fueron de 3,0 y 3,0 para los lugares de inyección del brazo y la pierna, respectivamente. No se observaron diferencias significativas en los valores medios de TC de la aorta ascendente, la arteria pulmonar y la vena cava superior izquierda; el valor de DE; la RCR; y las puntuaciones de visualización del brazo y la pierna.

ConclusionesLos valores de TC del lumen de los vasos sanguíneos y las puntuaciones de visualización de las imágenes 3D observados durante la realización de una ACT en pacientes neonatos y lactantes con cardiopatías congénitas son los mismos, independientemente de si el lugar de inyección es el brazo o la pierna.

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is a common condition with varying incidence rates of 4–6 cases per 1000 live births, with complex forms of the disease included.1 Pediatric patients with particularly severe CHD are detected within 1 year of birth because of severity due to the disappearance of the short circuit at neonatal and infant patients.2

Cardiac computed tomography angiography (CCTA) delineates extracardiac morphology and evaluates the airway simultaneously with a better spatial, temporal, and contrast resolution. In addition, recent advances in CT equipment and techniques have limited the radiation exposure of patients.3–11 Therefore, CCTA is widely used to evaluate CHD for its potential advantages, namely, decreased scan durations, reduced motion artifacts, and reduced need for sedation.12,13

The use of a contrast medium (CM) is effective in evaluating the structure of the heart and lumen of the blood vessels, but it can be difficult to evaluate stenosis and the microvessels near the injection site because of the artifacts caused by the CM. Consequently, pediatric patients with high radiation sensitivity must avoid rescanning.14 Therefore, obtaining CCTA images with optimal injection location such as the arm or leg is important to avoid the artifacts caused by the CM. However, it is unknown whether contrast enhancement changes when either the arm or leg was the injection location in neonatal and infant patients. If it changes, we must increase or decrease the CM dose and injection rate.

This study compares the CT numbers and visualization scores of the three-dimensional (3D) images of the lumens of the blood vessels in the arm or leg as the injection location during CCTA in neonatal and infant patients.

Materials and methodsThis retrospective study was approved by our institutional review board, and the requirement for informed consent was waived.

PatientsBetween January 2017 and January 2020, 253 consecutive patients were considered for inclusion. We used a logistic regression model to estimate the propensity scores of each patient. The propensity scores were used as a function of the patient demographic data, including age, body weight, and injection location (right or left side). Then, we performed a one-to-one matching analysis based on the estimated propensity scores of each patient to determine whether the injection location is at the arm or leg. Finally, 116 neonatal and infant patients (the injection location of 58 patients aged 0.1–12.0 months was the right side of the arm [right arm group], and the injection location of 58 patients aged 0.1–12.0 months was the right side of the leg [right leg group]) were enrolled.

The patients in the right arm group underwent CCTA to evaluate cyanotic heart disease (n = 28), acyanotic heart disease (n = 24), aortic coarctation (n = 5), and vascular ring (n = 1), whereas those in the right leg group underwent CCTA to evaluate cyanotic heart disease (n = 31), acyanotic heart disease (n = 20), aortic coarctation (n = 6), and vascular malformation (n = 1). Their serum creatinine levels were obtained within 3 months before the CCTA studies, and their estimated glomerular filtration rates were calculated using the modified isotope-dilution mass spectrometry formula.

CT scanningAll patients were scanned using a 64-row detector CT scanner (Lightspeed VCT; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA), and helical scans were acquired. The CT scanning parameters were as follows: rotation, 0.4 s; detector row width, 0.625 mm; helical pitch, 1.375 (beam pitch); table movement, 137.5 mm; scan field of view (FOV), 50 cm; kVp, 80; and mA, 40–100. Image reconstruction was in a 10–15-cm display FOV depending on the body size of the patient. All scans were from the top of the apical portion of the lung to the level of the inferior margin of the cardiac apex in the craniocaudal direction when an arm vein was the injection location and caudocranial when a leg vein was the injection location. Because for the purpose of reducing artifacts from CM.

Contrast injection protocolsWe injected a diluted CM (Omnipaque 300; Daiichi Sankyo, Tokyo, Japan) through a 24-gauge catheter into the antecubital or dorsal vein using a power injector (Dual Shot GX 7; Nemoto Kyorindo Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The administered iodine dose was 600 mg/kg body weight. In the 50% diluted CM injection protocol, the injection volume was TBW × 4.0 mL (CM: TBW × 2.0 mL and saline; BW × 2.0 mL) delivered in 16 s. After the CM was injected, 5 mL of physiological saline was flushed at the same injection rate. The acquisition of dynamic monitoring scans began 10 s after the start of the CM injection. To monitor the ascending aorta, we obtained dynamic scans (80 kVp, 10 mAs); the interscan interval was 1.0 s. Acquisition of the dynamic monitoring scans began 10 s after the start of CM injection. An ROI was placed in the ascending aorta to obtain a time attenuation curve for aortic peak-time measurements. We performed helical scans 2 s after the end of the CM injection with 5 mL of physiological saline flushing.

Data analysisWe recorded the CT dose volume index (CTDIvol) and dose length product (DLP), and they are routinely displayed on our scanner console monitor. The effective radiation dose (ED) was calculated by multiplying the total DLP by a constant (k = 0.082 mSv/mGy/cm) that is based on age-, tube voltage-, and region-specific pediatric DLP conversion coefficients from the International Commission on Radiological Protection Publication 103.15 We placed a circular region of interest with 10–20 mm diameter on the contrast-enhanced CCTA images. The mean CT numbers (in Hounsfield units [HU]) of the pulmonary artery, ascending aorta, and left superior vena cava were recorded for all neonatal and infant patients using a CT console monitor. To calculate the contrast–noise ratio (CNR),9 the mean CT number and mean image noise (SD of the CT number) of the muscle were displayed on the CT console monitor. We compared the mean CT numbers of the pulmonary artery, ascending aorta, and left superior vena cava; CNR; and radiation dose between the arm and leg as the injection locations.

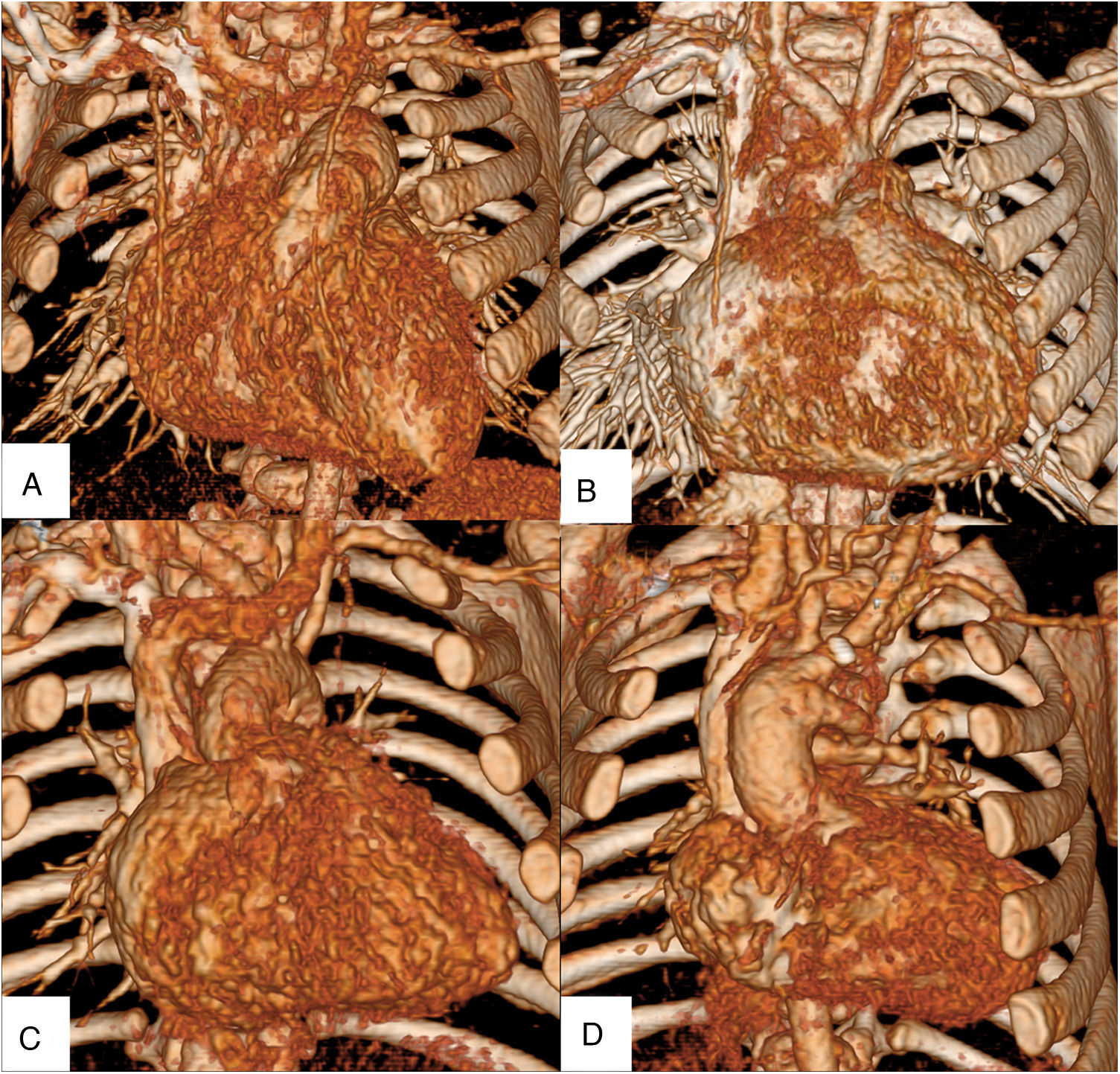

Visual inspection of the CCTA imagesA diagnostic radiologist and pediatric cardiologist with 33 and 28 years of experience, respectively, performed qualitative evaluation of the internal thoracic arteries (ITAs). They individually inspected 58 randomized volume rendering images acquired from the right arm and right leg groups. Both observers visually evaluated the ITAs using a four-point scale: grade 4, the main trunk of the ITA was completely demonstrated (Fig. 1a); grade 3, the entire ITA was demonstrated (Fig. 1b); grade 2, the ITA was partially demonstrated (Fig. 1c); and grade 1, the ITA was not demonstrated (Fig. 1d). When their initial assessment differed, the images were inspected again, and the final score was determined by consensus. All images were presented on a digital picture archiving and communication system using a diagnostic workstation (Advantage Workstation, version 4.2; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA).

A diagnostic radiologist and pediatric cardiologist individually inspected 58 randomized volume rendering images acquired from the right arm or right leg groups. Both observers visually evaluated the internal thoracic arteries (ITAs) using a four-point scale: grade 4, the main trunk of the ITA was completely demonstrated (a); grade 3, the entire ITA was demonstrated (b); grade 2, the ITA was partially demonstrated (c); and grade 1, the ITA was not demonstrated (d).

To determine the male–female ratio, we used the chi-square test. To compare the mean CT numbers of the pulmonary artery, ascending aorta, and left superior vena cava; CNR; CTDIvol; DLP; ED; and median visual evaluation scores, we used the Mann–Whitney U test. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using a free statistical software (R, version 3.0.2; http://www.rproject.org/).

ResultsThe patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the arm and leg as injection locations.

Patient Characteristics.

| Injection location | Right arm | Right leg | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of the patients | 58 | 58 | |

| Sex (male/female) | 26/32 | 30/28 | .67 |

| Age (months) | 5.1 (0.1–12.0) | 5.0 (0.1–12.0) | .86 |

| Height (cm) | 63.7 (47.0–100.0) | 63.3 (47.0–105.5) | .71 |

| Weight (kg) | 4.6 (2.0–10.0) | 4.7 (2.0–10.0) | .56 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 11.1 (7.0–17.2) | 11.5 (7.0–17.1) | .62 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 125.0 (98.0–153.0) | 127.0 (100.0–155.0) | .49 |

The mean CT numbers for the arm and leg as the injection locations were 479.4 and 461.3 HU in the ascending aorta, 464.2 and 448.1 HU in the pulmonary artery, and 232.8 and 220.1 HU in the left superior vena cava, respectively. The SD and CNR values were 38.9 HU and 12.1 when the arm was the injection location and 39.1 HU and 12.3 when the leg was the injection location. The mean CT numbers of the ascending aorta, pulmonary artery, and left superior vena cava; SD values; and CNR values had no significant differences between the arm and leg injection locations (Table 2).

Contrast enhancement, Radiation Dose, Image noise, and Contrast-to-noise ratio.

| Injection location | Right arm | Right leg | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ascending aorta (HU) | 479.4 (278.0–675) | 461.3 (280–701) | .37 |

| Pulmonary artery (HU) | 464.2 (293–701) | 448.1 (280–712) | .29 |

| Left superior vena cava (HU) | 232.8 (54–449) | 220.1 (53–512) | .45 |

| Computed tomography dose index volume (mGy) | 0.5 (0.3–0.9) | 0.5 (0.2–0.9) | .94 |

| Dose length product (mGy/cm) | 7.3 (3.8–14.5) | 7.2 (2.3–16.3) | .77 |

| Effective dose (mSv) | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) | 0.6 (0.2–1.3) | .77 |

| Standard deviation of CT number (HU) | 38.9 (34.0–48.0) | 39.1 (33.0–49.0) | .43 |

| Contrast–noise ratio | 12.1 (10.5–17.1) | 12.3 (11.0–16.4) | .41 |

The CTDIvol, DLP, and ED, respectively, were 0.5 mGy, 7.3 mGy/cm, and 0.6 mSv when the arm was the injection location and 0.5 mGy, 7.2 mGy/cm, and 0.6 mSv when the leg was the injection location. There were no significant differences in the CTDIvol, DLP, and ED between the arm and leg injection locations (Table 2).

The median visualization scores of volume rendering of the 3D images were 3.0 and 3.0 for the arm and leg injection locations, respectively (Fig. 2). The Cohen value for interobserver agreement was 0.71.

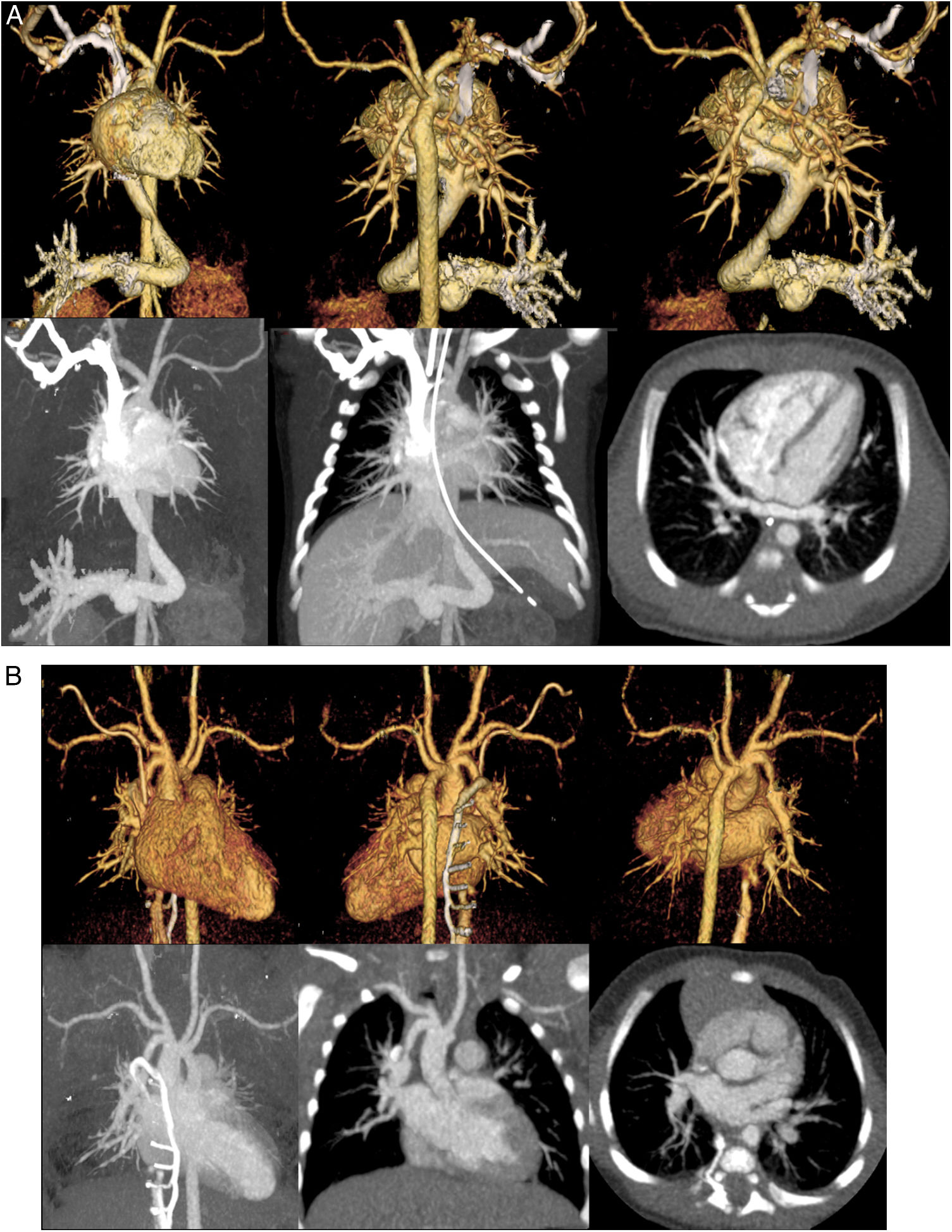

The representative volume rendering and maximum intensity projection of the CCTA images for both injection locations are shown in Figs. 3a and 3b.

a) A 4-day-old female with infracardiac anomalous pulmonary venous returns total anomalous pulmonary venous connection (TAPVC). Volume rendering for the front view (a). Volume rendering for the back view (b). Volume rendering for the back view without the descending aorta (c). Maximum intensity projection (d), slab maximum intensity projection (e), and axial image. We detected the infracardiac anomalous pulmonary venous returns using echocardiography, and we performed CCTA to understand the heart morphology. We used the right arm as the injection site. If we used the right leg as the injection location, the ductus venosus and pulmonary veins might not be evaluated. b) A 5-week-old female with vascular malformation. Volume rendering for the front view (a). Volume rendering for the back view (b). Volume rendering for the back view without the vein (c). Maximum intensity projection (d), slab maximum intensity projection (e), and axial image. We detected the vascular malformation using echocardiography, and we performed CCTA to understand the heart morphology. We used the right leg as the injection site. If we used the right arm as the injection location, the junction of the brachiocephalic artery and right pulmonary artery might not be evaluated.

This study shows that the CT numbers of the lumens of the blood vessels and the visualization scores of volume rendering of the 3D images were not significantly different between the arm and leg as the injection locations.

It is not necessary to change the amount of CM or injection rate for the arm and leg injection locations. Yang et al.16 reported that there was no significant difference in the mean attenuation among the head, arm, and leg vein injection sites of the heart chamber, pulmonary artery, and aorta, respectively, using mechanical injection of CM. It was almost similar to the results of this study. However, the difference between our study and that of Yang et al. was the patients’ age. Their study sample was from the 4–36 months age group. In pediatric patients, severe CHD is detected within 1 year of birth.2 Therefore, we used the estimated propensity scores as a function of the patient demographic data, including age, body weight, and injection location (right or left side) for the arm (n = 58) and leg (n = 58) injection sites in neonatal and infant patients. Our study is the first to evaluate CM injection location effectiveness when performing CCTA studies in neonatal and infant patients using estimated propensity scores.

The contrast enhancement at the lumen of the blood vessels in both the arm and leg was equal, which, we think, changes based on the body proportion during human growth after birth. However, in neonatal and infant patients, we believe that the distance from the arm or leg to the heart hardly changes. Consequently, CM was immediately followed by a saline flush in all patients.17 Small volumes (10–20 mL) of CM administered via the vein can be retained for some time in the dead space in the injection location and heart in adults. Therefore, the CM may have been unavailable immediately after the termination of contrast injection.18,19 However, the dead space in the injection location and heart is smaller in neonatal and infant patients than in adults. Various factors affected our results. There may have been no difference in the contrast enhancement in both injection locations.

Schooler et al. show that diagnostic quality thoracic CTA can be achieved with hand injection of IV contrast material in infants and young children independent of IV access sites.20 However, for the results of this study can be used by the radiologists who often have to make a decision regarding the use of hand injection of IV contrast material in infants and young children with a small IV catheter at various access sites when performing thoracic CTA. The injection sites in the wrong place could be change diagnostic quality.

It is necessary to change the injection location depending on the target cardiac chambers. In supracardiac total anomalous pulmonary venous connection (TAPVC), the pulmonary veins drain via the innominate vein to the right atrium.21 The injection of the CM into the arm caused image blurring with the artifacts of the ascending aorta because of the high concentration of the CM in the superior vena cava, even though the CM was immediately followed by a saline flush. In infracardiac anomalous pulmonary venous returns TAPVC, the pulmonary veins drain via the ductus venosus to the right atrium.21 The injection of the CM into the leg caused image blurring with the artifacts of the ductus venosus because of the high concentration of the CM in the superior vena cava, even though the CM was immediately followed by a saline flush. Therefore, echocardiography is the first-line diagnostic technique to determine the optimal injection location.

Some limitations in this study exist. First, the range of patient sizes might be smaller than Western populations, and the applicability of our results to populations having greater body weights needs to be verified. Second, all procedures and analyses were performed in a single center. Third, we did not investigate the relationship between contrast enhancement and image quality. Lastly, the two groups have different CHD abnormalities, which could cause different homodynamic circulations and attenuation of the heart chambers and great vessels.

ConclusionThe CT numbers of the lumens of the blood vessels and visualization scores of volume rendering of 3D images are equal for both the arm and leg used as the injection sites during CCTA in neonatal and infant patients with CHD.

Authorship- 1.

Responsible for study integrity: TM, YF

- 2.

Study conception: TM, TS, MT

- 3.

Study design: TM, TS, MT

- 4.

Data acquisition: TM, YY, SM, TY, TO

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: TM, YY, SM, TY, TO

- 6.

Statistical processing: TM, TN

- 7.

Literature search: TM, YF, TN

- 8.

Drafting of the manuscript: TM, YF

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: TS, MT, SA, JH

- 10.

Approval of the final version: KA

None.