Macrocephaly is a clinical term defined as an occipitofrontal circumference more than two standard deviations above the mean. It is present in 5% of children and is a common indication for imaging studies. There are multiple causes of macrocephaly; most of them are benign. Nevertheless, in some cases, macrocephaly is the clinical manifestation of a condition that requires timely medical and/or surgical treatment. The importance of imaging studies lies in identifying the patients who would benefit from treatment. Children with macrocephaly associated with neurologic alterations, neurocutaneous stigmata, delayed development, or rapid increase of the circumference have a greater risk of having disease. By contrast, parental macrocephaly is predictive of a benign condition. Limiting imaging studies to patients with increased risk makes it possible to optimize resources and reduce unnecessary exposure to tests.

Macrocefalia es un término clínico definido como el incremento de la circunferencia occipitofrontal por encima de dos desviaciones estándar. Se presenta en el 5% de los niños y es una indicación frecuente de estudios radiológicos. Existen múltiples causas de macrocefalia, que corresponden mayoritariamente a condiciones benignas. Sin embargo, en algunos casos es la manifestación clínica de una patología que requiere una oportuna intervención médico-quirúrgica. La relevancia del estudio radiológico radica en la identificación de estos pacientes. Aquellos niños que se presentan con macrocefalia asociada a alteraciones neurológicas, estigmas neurocutáneos, retraso del desarrollo o rápido aumento de la circunferencia craneal poseen un riesgo aumentado de presentar patología. Por el contrario, el antecedente de macrocefalia parenteral es predictivo de una condición benigna. Acotar el estudio radiológico a los pacientes de mayor riesgo permite optimizar recursos y disminuir la exposición innecesaria a exámenes.

Macrocephaly is a clinical term defined as an increase in occipitofrontal circumference by more than two standard deviations (SDs), or in the 97th percentile, for age and sex. It affects 5% of the population.1,2 Macrocephaly must be distinguished from megalencephaly, corresponding to enlargement of brain parenchyma by two SDs above the mean for age.3–6 Suitable radiological examination of patients with a diagnosis of macrocephaly requires knowledge of normal skull development and awareness of the various aetiologies of an increase in head circumference (HC). In the first 12 months of life, the brain parenchyma grows very rapidly, and therefore so does the skull. This is achieved because the cranial sutures and fontanelles are open.7 Between 12 and 24 months of age, brain growth starts to slow down; between 2 and 5 years, it is significantly slower, and after 5 years, it is minimal.8 With this, the cranial sutures start to close and the skull loses its capacity for expansion. Therefore, before the age of five, but in particular before age two, situations involving an increase in intracranial volume, such as hydrocephalus, can cause the skull to expand, as long as they develop gradually. By contrast, if the increase in intracranial volume has an acute onset, the skull does not expand and the patient will have symptoms of intracranial hypertension.9 Increased thickness of the cranial vault, as seen in some bone diseases, can also cause macrocephaly, although this is an uncommon cause.

Macrocephaly is a common indication in radiological studies; hence, the situations in which they should be performed and the techniques that should be used to perform them must be known. The objective of this article is to set out updated recommendations in relation to the radiological study of children with macrocephaly, briefly review the main entities that cause an increase in HC and propose an algorithm for the diagnosis of these entities.

Why perform radiological studies in macrocephaly?Macrocephaly is a clinical finding that may have a wide variety of causes. Its most common aetiologies are non-pathological conditions not associated with other clinical abnormalities, such as familial megalencephaly and benign enlargement of the subarachnoid space.10 Another group of patients consists of those who have an aetiological diagnosis associated with macrocephaly, such as neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) or tuberous sclerosis, usually in association with neurocutaneous stigmata.11 However, in a small group of patients, macrocephaly may be secondary to an increase in intracranial contents, as in hydrocephalus, subdural collections, cysts and intracranial tumours.12 The importance of neuroradiology studies in patients with macrocephaly lies in making a timely diagnosis in these children.

In what situations should radiological studies be performed?Given the wide variety of diagnoses that present with macrocephaly and the high rates of causes that do not signify a disease state, it is important to pursue an appropriate strategy for the radiological study of these patients. The best strategy would detect cases with significant intracranial disease, for their medical or surgical management, and would minimise unnecessary studies, which could involve exposure to ionising radiation or the use of anaesthesia, and furthermore could drive up healthcare costs. To date, no clinical guidelines have been published by the leading medical scientific associations in relation to the indications for radiological studies in children with macrocephaly. In the presence of neurological symptoms, developmental abnormalities or neurocutaneous stigmata, there is a widespread consensus that these patients must undergo radiological studies. Such were the findings of Haws et al., in whose study 30% of patients with macrocephaly and neurological deficits had pathological findings on radiological studies.13 In the same vein, Sampson et al. found in a series of 169 children with macrocephaly that patients with abnormal radiological studies had higher odds of developmental delays and neurological symptoms. For their part, Zahl et al. found that, in 46% of 298 children with intracranial expansive conditions, the initial symptom that led to diagnosis was an increase in HC. This confirms the usefulness of HC measurement in health check-ups.14 Indications for radiological studies are more heavily debated in patients with macrocephaly but none of the above-mentioned risk factors, since the cause is benign in the vast majority of cases. However, a small percentage of those patients have significant disease. This was recently found by Thompson et al. in a series of 440 infants with macrocephaly studied initially with transfontanellar brain ultrasound (US), where 2.2% showed significant findings.15 These results were similar to those of Naffaa et al., who found a corresponding rate of 1.8% in 326 infants.16 Thompson et al. suggested US in all asymptomatic infants in order to identify those 2% of abnormalities. By contrast, Naffaa et al. suggested clinical surveillance as the strategy with the best performance.

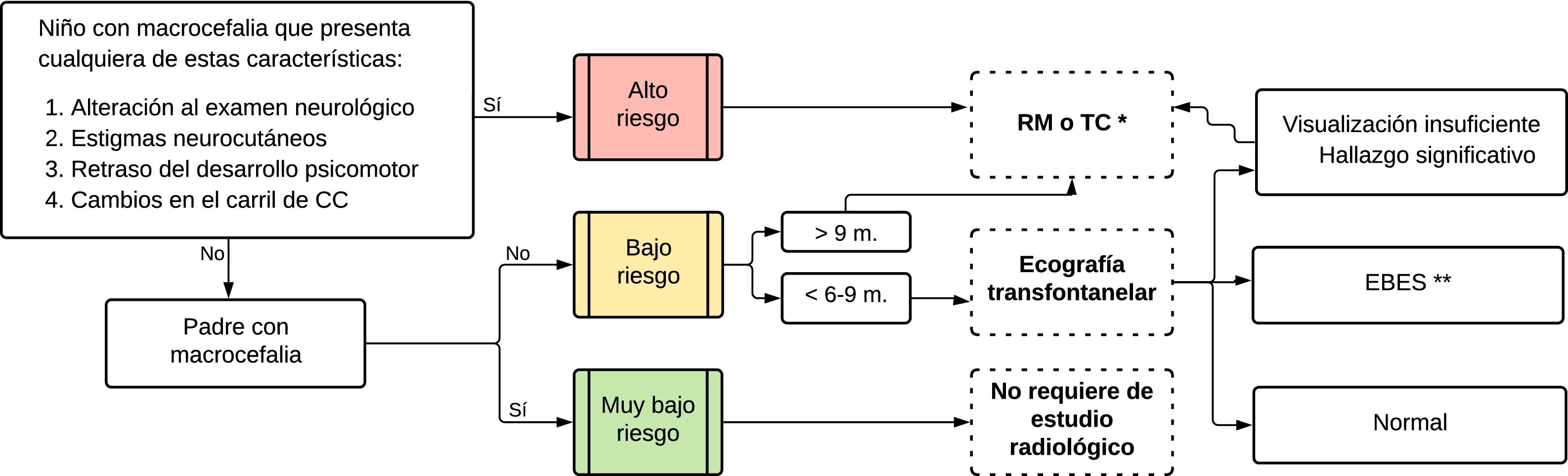

In light of the information above and based on our clinical practice, we have prepared a strategy for optimising radiological evaluation of children with macrocephaly, establishing three risk groups. The high-risk group includes children with neurological abnormalities, neurocutaneous stigmata, developmental delays and a rapid increase in HC. Unlike other groups,10,11 we considered a rapid increase in HC to be a high-risk characteristic a priori since, while it may be seen in infants with benign enlargement of the subarachnoid space (BESS), it is highly indicative of expansive conditions such as congenital hydrocephalus, certain tumours and subdural collections — sometimes as a lone clinical finding. We also established a very low-risk category, which includes patients without the above-mentioned risk factors who have at least one parent with macrocephaly, as having a parental history of macrocephaly is predictive of having a normal radiological study.12 Finally, the low-risk group features patients with no high risk factors and no parental history of macrocephaly. We recommend that only very low-risk patients may go without a radiological evaluation. In low-risk patients, a US evaluation is recommended, technique and conditions permitting. A summary of recommendations for radiological study of macrocephaly appears in Fig. 1.

What radiological technique should be used?The open anterior fontanelle, in infants six to nine months of age, makes US a reasonable initial study when there is low suspicion of disease (low-risk group). Its low cost, widespread availability, lack of radiation and absence of requirements for anaesthesia render it a good initial diagnostic tool. This technique identifies patients with BESS or subdural collections (apart from small ones in the convexity) and rules out hydrocephalus primarily. It can also, to varying extents, identify other abnormalities such as expansive conditions and parenchymal abnormalities.17,18 Should a pathological finding be identified, the study should be continued with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT). CT is the modality of choice if the patient is clinically unstable or to study bone abnormalities, such as dysplasias. MRI, given its excellent contrast resolution, is the examination of choice in the remaining situations. It carries the major advantage of not using ionising radiation, although it could require the use of anaesthesia, with the drawbacks that this entails. Abbreviated MRI protocols, based on acquisition of ultrarapid sequences, represent a suitable alternative for the evaluation of patients with macrocephaly, since they rule out abnormalities that require some sort of operation, thus avoiding the use of anaesthesia.10,19

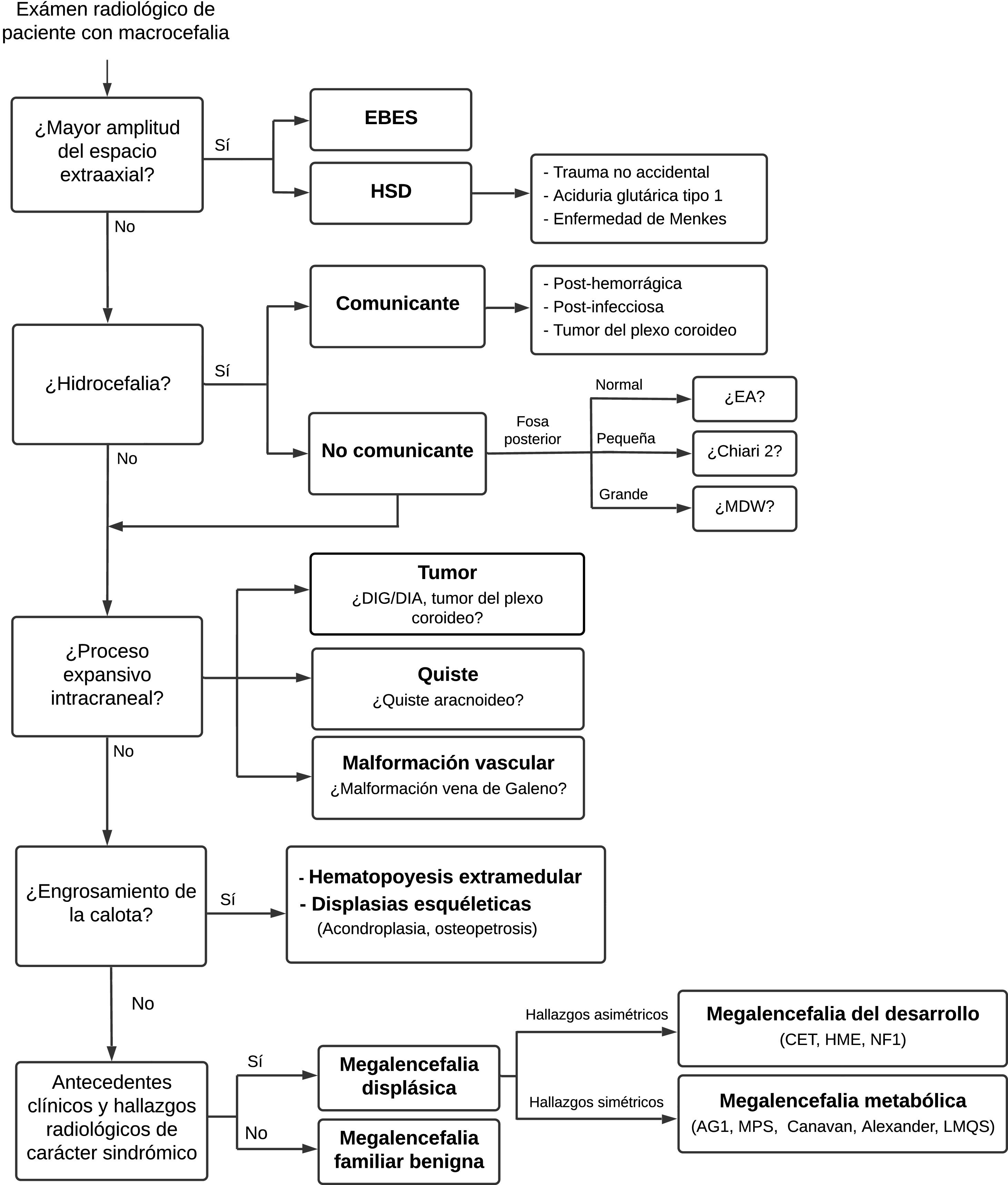

The main entities that may present with macrocephaly will be briefly reviewed and an algorithm for their diagnosis will be proposed (Fig. 2).

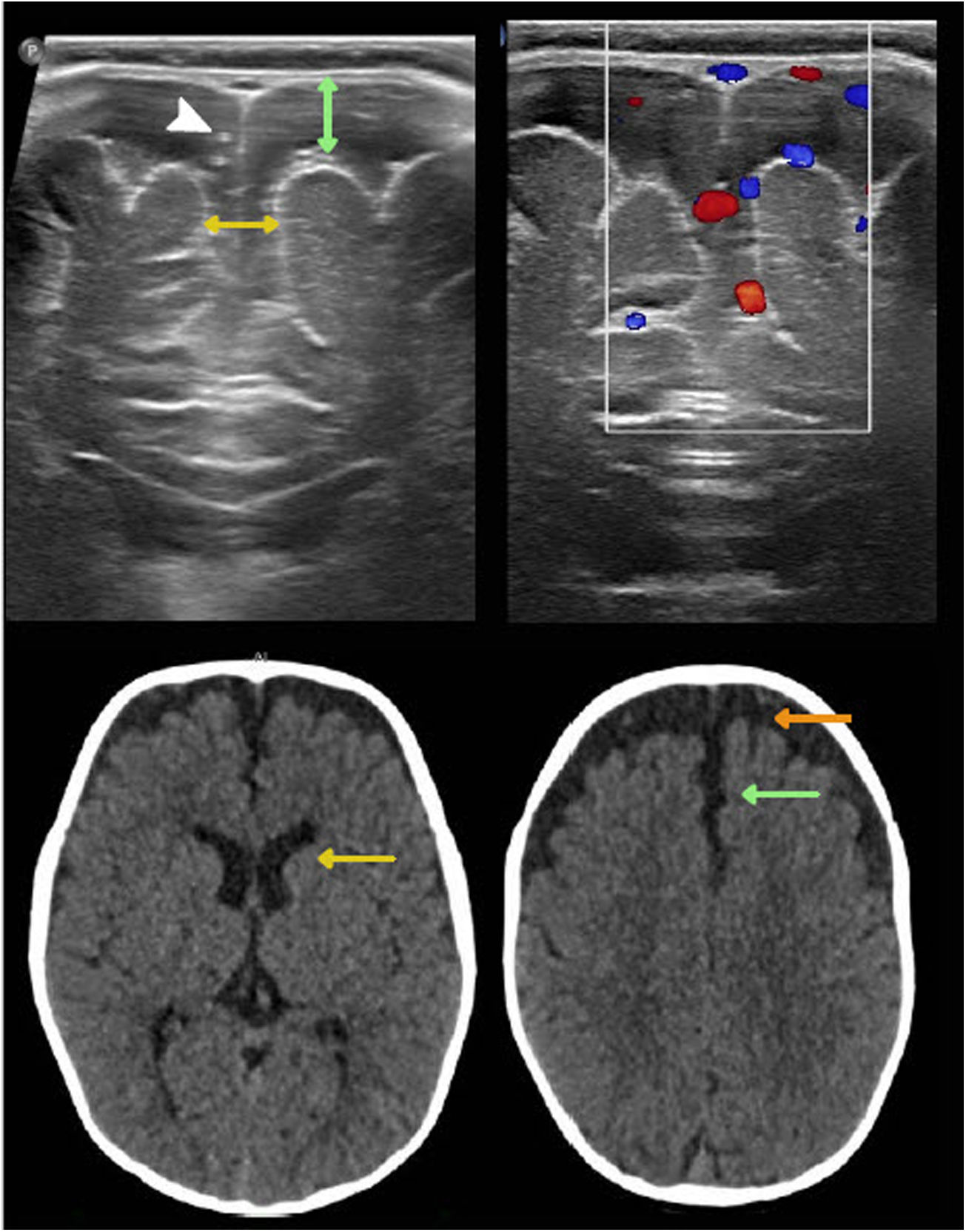

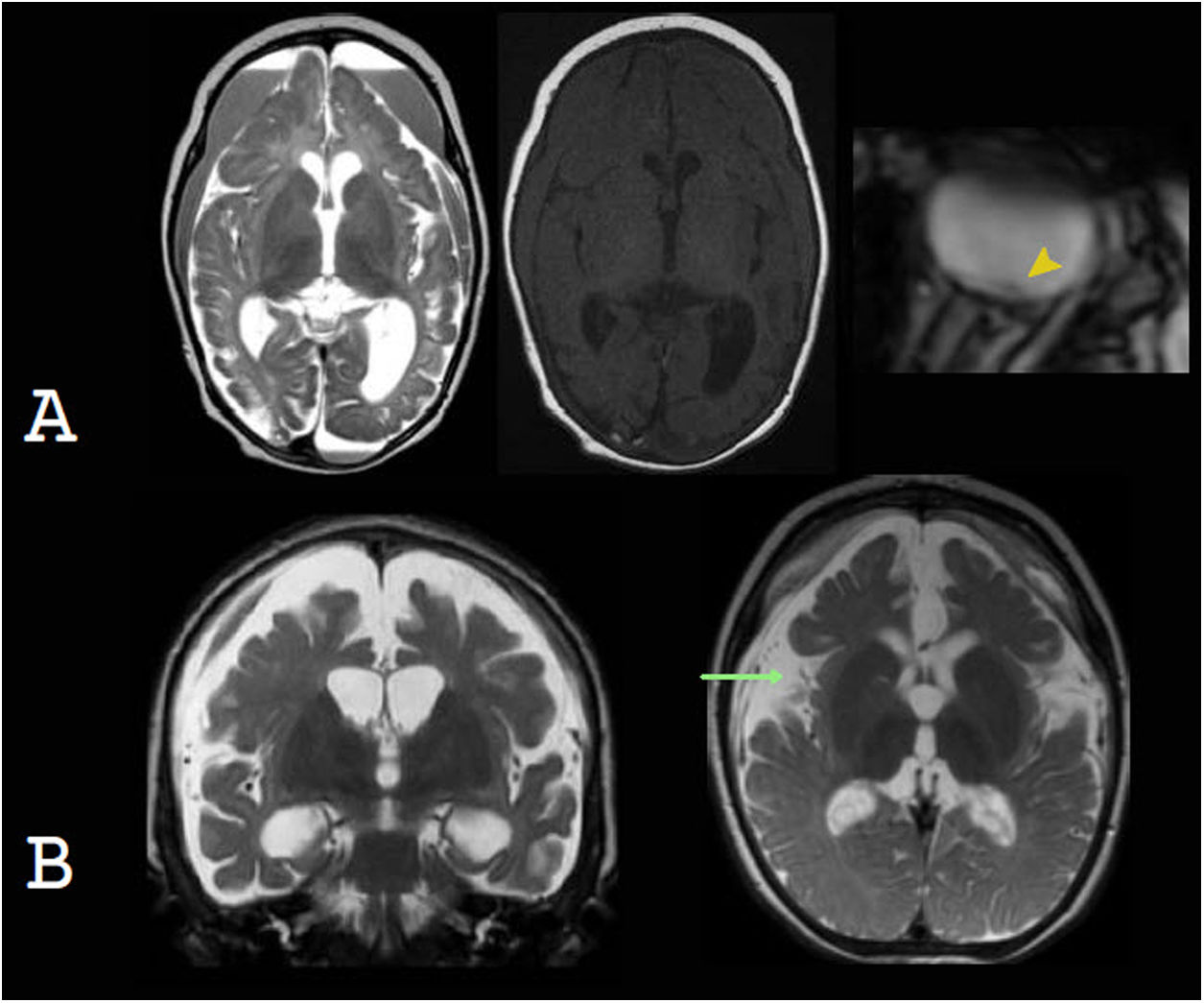

Benign swelling of the subarachnoid spaceOne of the main causes of macrocephaly, along with benign familial megalencephaly, is BESS. It may present with a rapid increase in head circumference in the first year of life.15 Its pathophysiology is linked to lower cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) absorption, due to either immaturity of the arachnoid villi or obstruction of venous drainage. This leads to an accumulation of CSF, resulting in skull distension and macrocephaly.20 Imaging shows characteristic enlargement of the frontal and temporal subarachnoid space, affecting the convexity, the anterior interhemispheric fissure and the Sylvian fissures. There may also be a slight increase in the size of the frontal horns. The echogenicity, density and signal should be the same as in the CSF and should not cause a compression effect. These findings normalise between two and three years and do not require radiological monitoring.21,22 In infants six to nine months of age, US enables suitable evaluation of this entity. To this end, the width of the subarachnoid space should be measured on the coronal plane, at the foramen of Monro. The most commonly used measurements are the distance between the inner table and the cerebral cortex and the interhemispheric width. The widths thereof vary with age but are always pathological when they exceed 10 mm.15 Echogenic vascular structures that exhibit colour Doppler flow are characteristically identified in their thickness. This allows them to be distinguished from subdural collections, which lack these structures23 (Fig. 3).

Benign enlargement of the subarachnoid space in a seven-month-old infant. Transfontanellar ultrasound shows the main determinations used to measure it: the distance between the inner table and the cerebral cortex (double green arrow) and the interhemispheric width (double yellow arrow). Above 10 mm they are pathological. Note the presence of punctiform echogenic images (white arrow tip) corresponding to vascular structures characteristic of this compartment and also seen with colour Doppler ultrasound. Computed tomography without contrast shows a greater width of the subarachnoid space of the frontal convexity (orange arrow), with compromise of the anterior interhemispheric fissure (green arrow) and a slight increase in the size of the frontal horns (yellow arrow). The density is the same as that of the cerebrospinal fluid and does not cause a mass effect.

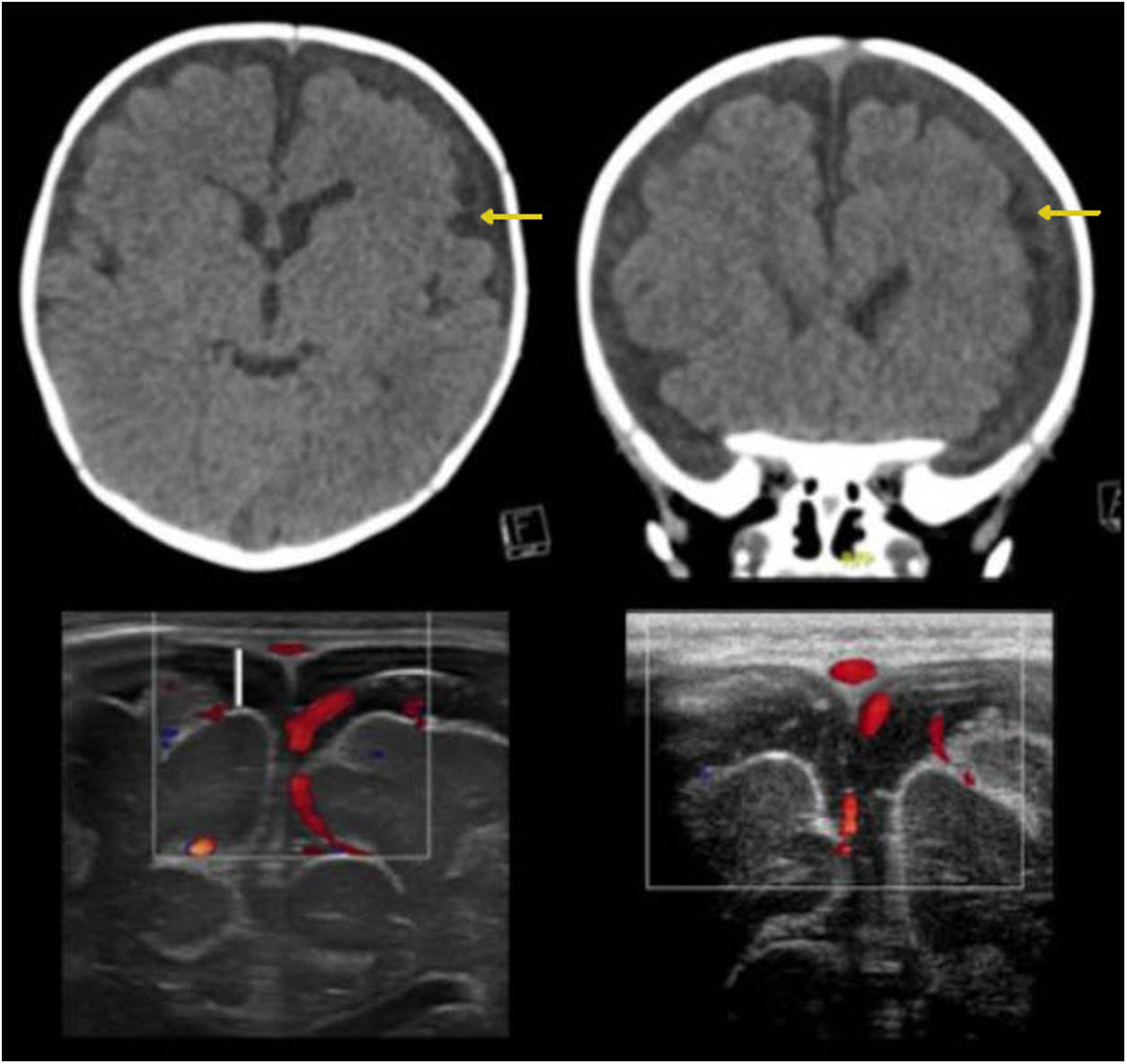

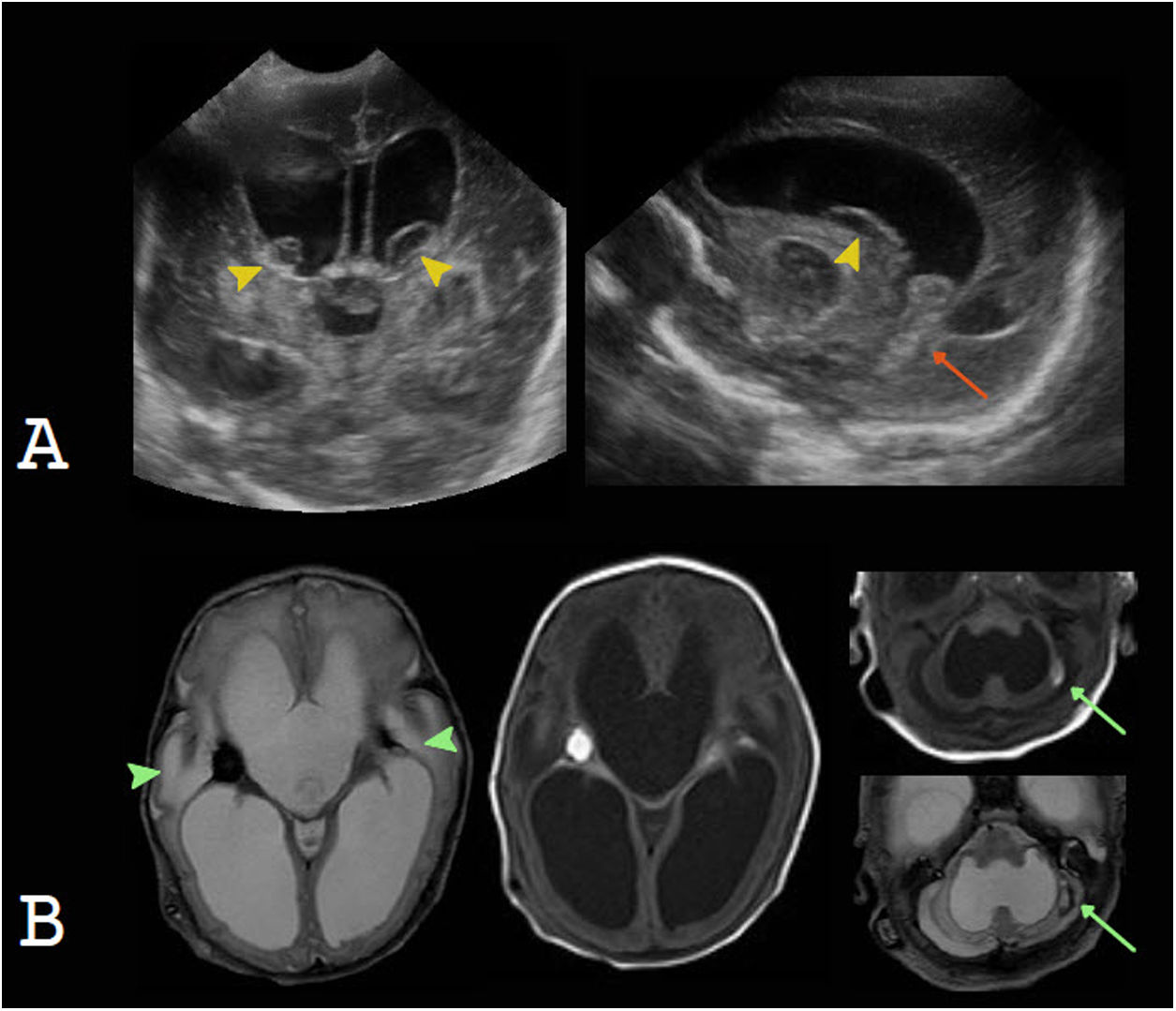

A great deal of literature has suggested that patients with BESS may develop subdural haematomas spontaneously or in the event of mild head trauma, explained by tearing of cortical veins which are found to be distended.24 This association, however, is uncommon. Thus, according to the latest consensus on abusive head trauma, published in 2018 by Choudhary et al., the presence of subdural haematomas in patients with BESS should raise suspicion of associated trauma, including non-accidental trauma25–28 (Fig. 4).

Benign enlargement of the subarachnoid space associated with bihemispheric subdural collections. The images in the top row correspond to computed tomography without contrast showing a slightly higher density of the subdural collections compared to the cerebrospinal fluid (yellow arrows). The images in the bottom row correspond to transfontanellar ultrasound. In the image on the left, bilateral subdural collections are identified as a fluid space with no vascular structures inside (white line). The image on the right corresponds to a follow-up after three months showing regression of the collections.

Subdural haematomas, in a context of non-accidental trauma (NAT), may cause macrocephaly. In a recent study of 28 children with confirmed NAT, 81% had a HC in the 90th percentile or above, and 69% had a HC in the 97th percentile or above. In fact, in some children, the only clinical sign of NAT was macrocephaly or a rapid increase in HC29,30 (Fig. 5).

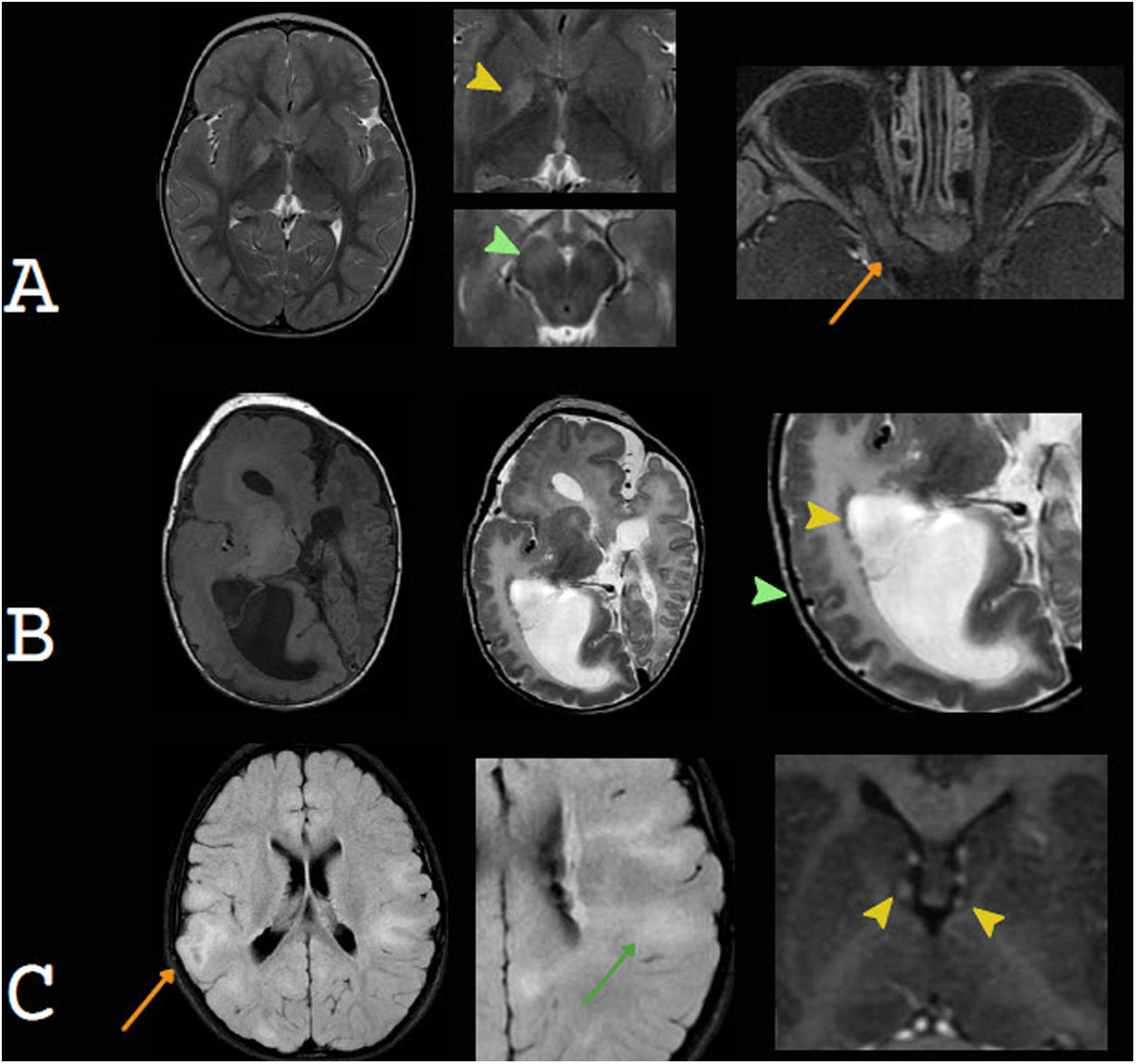

Subdural collections as a cause of macrocephaly. A) Non-accidental trauma. Despite the signs of atrophy of the brain parenchyma, the voluminous subdural collections, with blood contents, led a to a gradual increase in head circumference. Retinal haemorrhage, detected in T2* (yellow arrow tip), which is a significant element for diagnosis. B) Glutaric aciduria type 1. Bihemispheric blood collections, brain parenchymal atrophy, mild ventriculomegaly and a characteristic increased width of the Sylvian fissure are observed.

Another entity that may co-occur with subdural haematomas and macrocephaly is glutaric aciduria type 1 (GA1), an inborn error of metabolism caused by deficiency of glutaryl-coenzyme A-dehydrogenase, with deposition of organic acids in the brain. Macrocephaly presents at birth or develops soon afterwards, and is secondary to the presence of subdural collections and/or megalencephaly. The following are characteristic: a greater width of the frontotemporal subarachnoid space and of the Sylvian fissures; mild ventriculomegaly; subdural collections; and abnormalities of the basal ganglia, especially abnormalities of the putamen and late abnormalities of the white matter.31,32 The differential diagnosis should include Menkes disease, which typically presents with the triad of severe cerebral atrophy, subdural collections due to tearing of cortical veins and tortuous cerebral vessels.33–36

HydrocephalusHydrocephalus is a complication of various diseases in which the intraventricular CSF compartment is found to be enlarged. It may be congenital or acquired.20 It is caused by an imbalance between CSF production and absorption or by obstruction of CSF flow. If hydrocephalus is acute, the skull does not have the time to expand, and the patient presents signs and symptoms of intracranial hypertension. By contrast, if hydrocephalus develops gradually, the skull is able to expand, and the most consistent clinical finding is macrocephaly, with a change in the growth curve. Hydrocephalus is classified as communicating hydrocephalus when there is an obstruction in flow outside the ventricular system, as in post-haemorrhagic or post-infectious hydrocephalus, or there is overproduction of CSF, as in choroid plexus tumour, in which dilation of the entire ventricular system is observed. Non-communicating hydrocephalus is due to obstruction of CSF flow within the ventricular system or at the outlet of the fourth ventricle, and leads to ventricular dilation over the obstruction.10,20

Communicating hydrocephalusHydrocephalus occurs in 35% of premature infants with germinal/intraventricular matrix haemorrhage, and 15% of cases end up requiring a ventricular shunt.10 Germinal matrix haemorrhage is due to factors related to perinatal events and greater vessel fragility. US is the initial study of choice, since it enables evaluation of germinal matrix haemorrhage, which presents as an echogenic focus in the caudothalamic groove, with anterior extension, as well as measurement and monitoring of the course of hydrocephalus.23 Subsequent MRI can be used to evaluate foci of bleeding in other locations that are difficult to evaluate on ultrasound, such as the cerebellum, and to more accurately evaluate parenchymal lesions associated with hypoxic–ischaemic damage.37 Ventricular enlargement is due not only to hydrocephalus secondary to intraventricular haemorrhage, but also usually co-occurs with ex vacuo dilation due to periventricular white-matter damage (Fig. 6). Intraventricular haemorrhage in full-term newborns is less common than in preterm newborns, and may be due to coagulopathy, dehydration, hypoxic–ischaemic injury, venous thrombosis, infection or trauma. Radiological findings will be related to the aetiology of the bleeding and will require a specific study depending on the case.10

A and B) Intraventricular haemorrhage in a premature newborn as a cause of communicating hydrocephalus. Transfontanellar ultrasound shows blood contents in the caudothalamic groove, with a cystic appearance, in a later stage (yellow arrow tips); intraventricular blood contents (orange arrow); and severe hydrocephalus. Magnetic resonance imaging confirms these findings and enables evaluation of parenchymal involvement (green arrow tips) and a focus of cerebellar haemorrhage (green arrows).

Hydrocephalus may also be the result of a prenatal or postnatal infection, usually due to leptomeningeal compromise. The purulent contents that impede CSF circulation and inflammation of arachnoid granulations decrease CSF reabsorption, and cause hydrocephalus.10

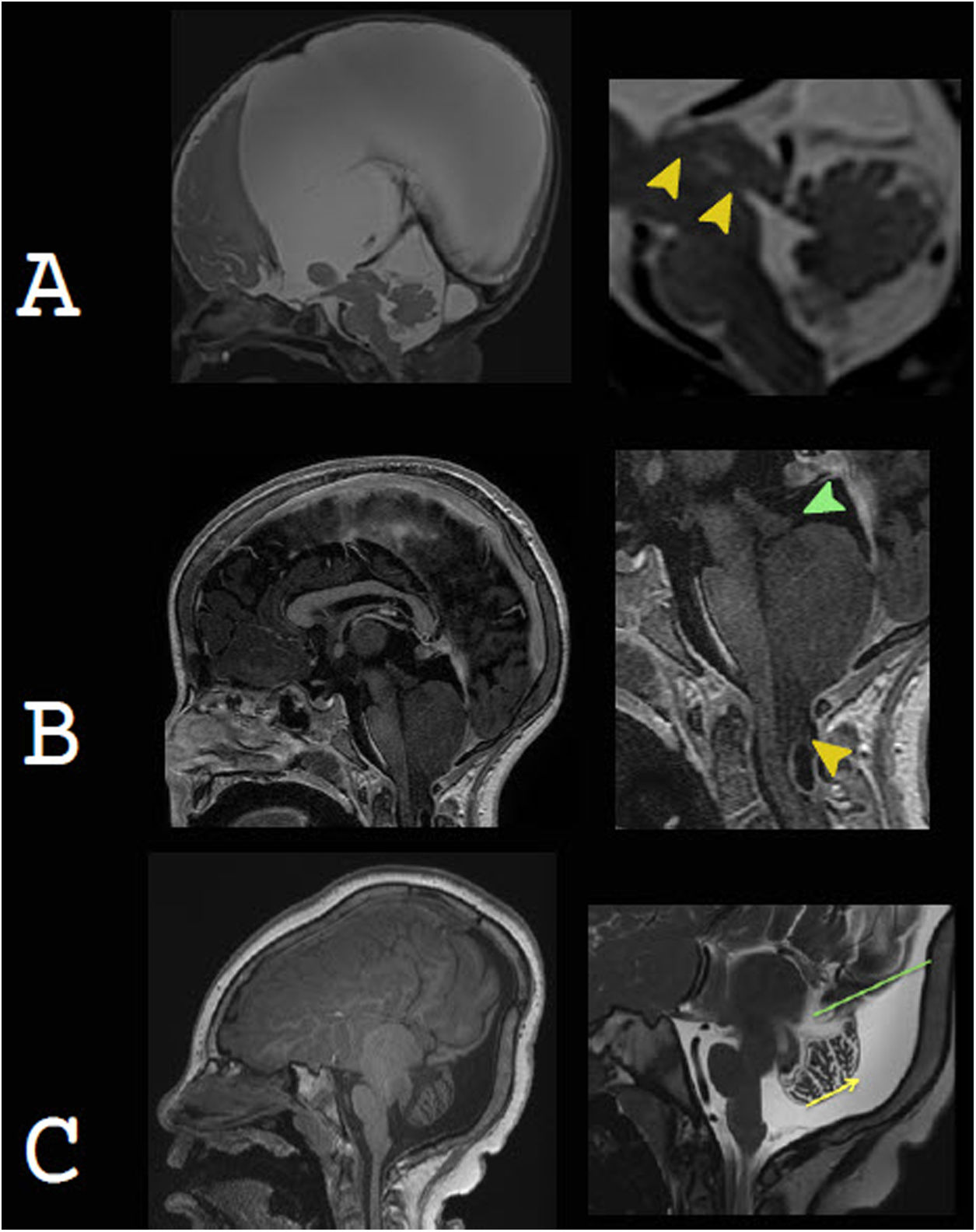

Non-communicating hydrocephalusAqueductal stenosis (AS) is the cause of approximately 20% of cases of congenital hydrocephalus, which usually present with macrocephaly, often as a sole clinical finding. AS is a generic term applied to all aqueduct obstructions, whose aetiologies are multiple and include both genetic and acquired forms.38,39 In radiological studies, isolated AS presents as supratentorial ventricular dilation and a fourth ventricle of a normal size. In addition to T1-weighted and T2-weighted conventional structural sequences, it is highly advisable to obtain T2-weighted 3D sequences, such as SPACE, CUBE or VISTA, which are sensitive to the pulsatile movement of CSF, and gradient echo 3D sequences such as CISS, FIESTA and DRIVE, which are not sensitive to pulsatile CSF movement but offer excellent spatial resolution (Fig. 7).

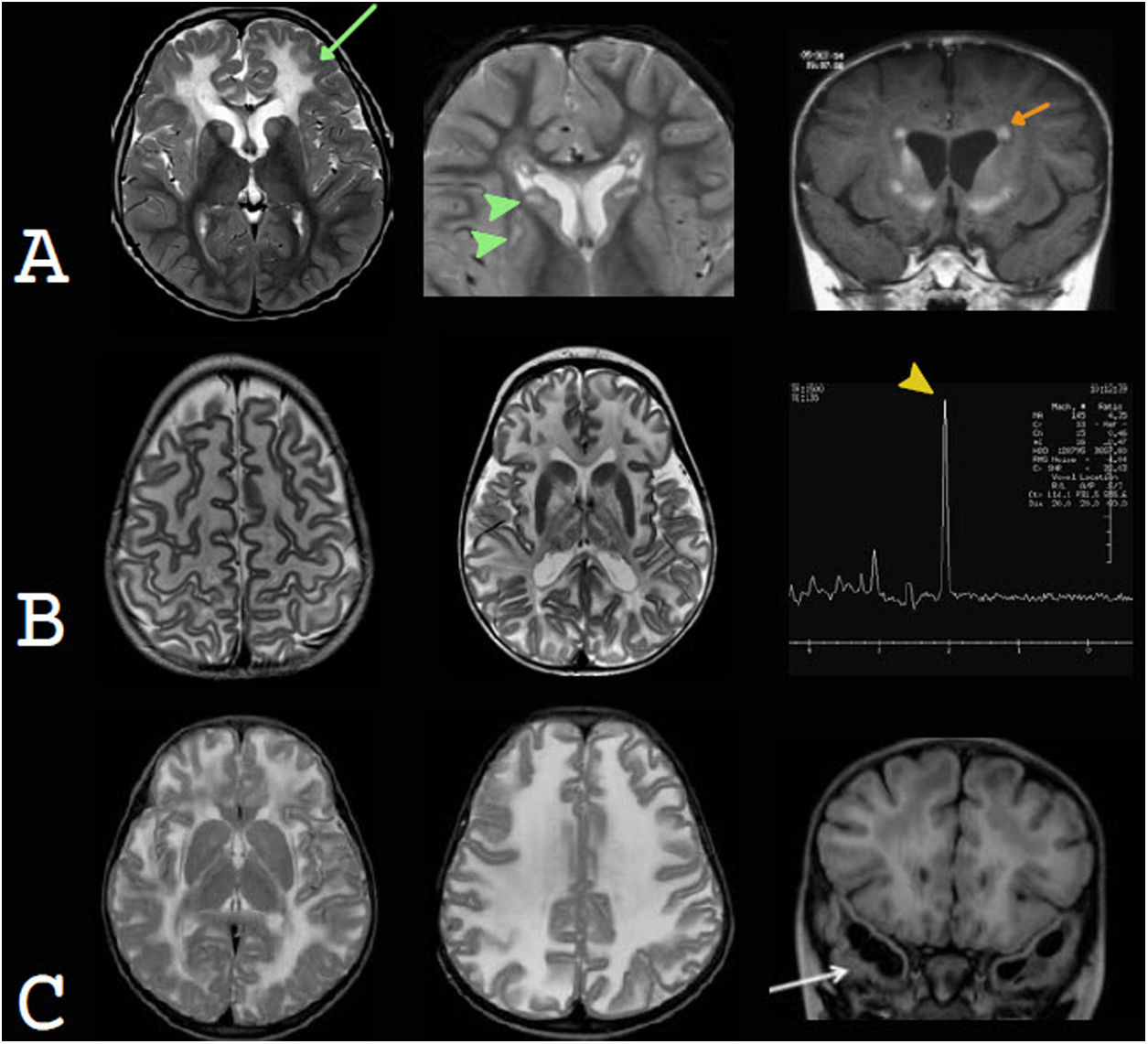

Non-communicating hydrocephalus as a cause of macrocephaly. A) Aqueductal stenosis as part of a complex brain malformation, due to mutation of the L1CAM gene, in a newborn with marked macrocephaly. The image on the right corresponds to magnetic resonance cisternography, based on steady-state gradient echo sequences. It distinguishes two areas of narrowing of the aqueduct (arrow tips). B) Chiari malformation type 2. Small posterior fossa and cerebellar tonsil descent (yellow arrow tip), leading to obstruction of cerebrospinal fluid and consequently hydrocephalus (currently shunted). Beaking of the tectal plate (green arrow tip) is characteristic. C) Dandy-Walker malformation. Enlargement of the posterior fossa with cystic dilatation of the fourth ventricle extending in a posterior direction. There is elevation of the torcula (green line), vermian hypoplasia and cephalic vermian rotation (yellow arrow). It is commonly associated with other abnormalities, as in this case, with dysgenesis of the corpus callosum and aqueductal stenosis.

Chiari malformation type 2 is the most common syndromic cause of hydrocephalus. It consists of a complex spectrum of abnormalities of the brain and skull base, almost invariably associated with a myelomeningocele. It is characterised by a small posterior cranial fossa, with hindbrain and cerebellar tonsil descent, leading to obliteration of CSF flow, which is what causes supratentorial hydrocephalus.10,40–43

Dandy-Walker malformation corresponds to a cystic malformation of the hindbrain. Its most common clinical sign is macrocephaly in the first year of life.44 Radiological studies show an enlargement of the posterior fossa, secondary to cystic dilation of the fourth ventricle, torcular–lambdoid inversion, cerebellar and vermian hypoplasia, and cephalic vermian rotation. It is associated with hydrocephalus in 70%–90% of cases.

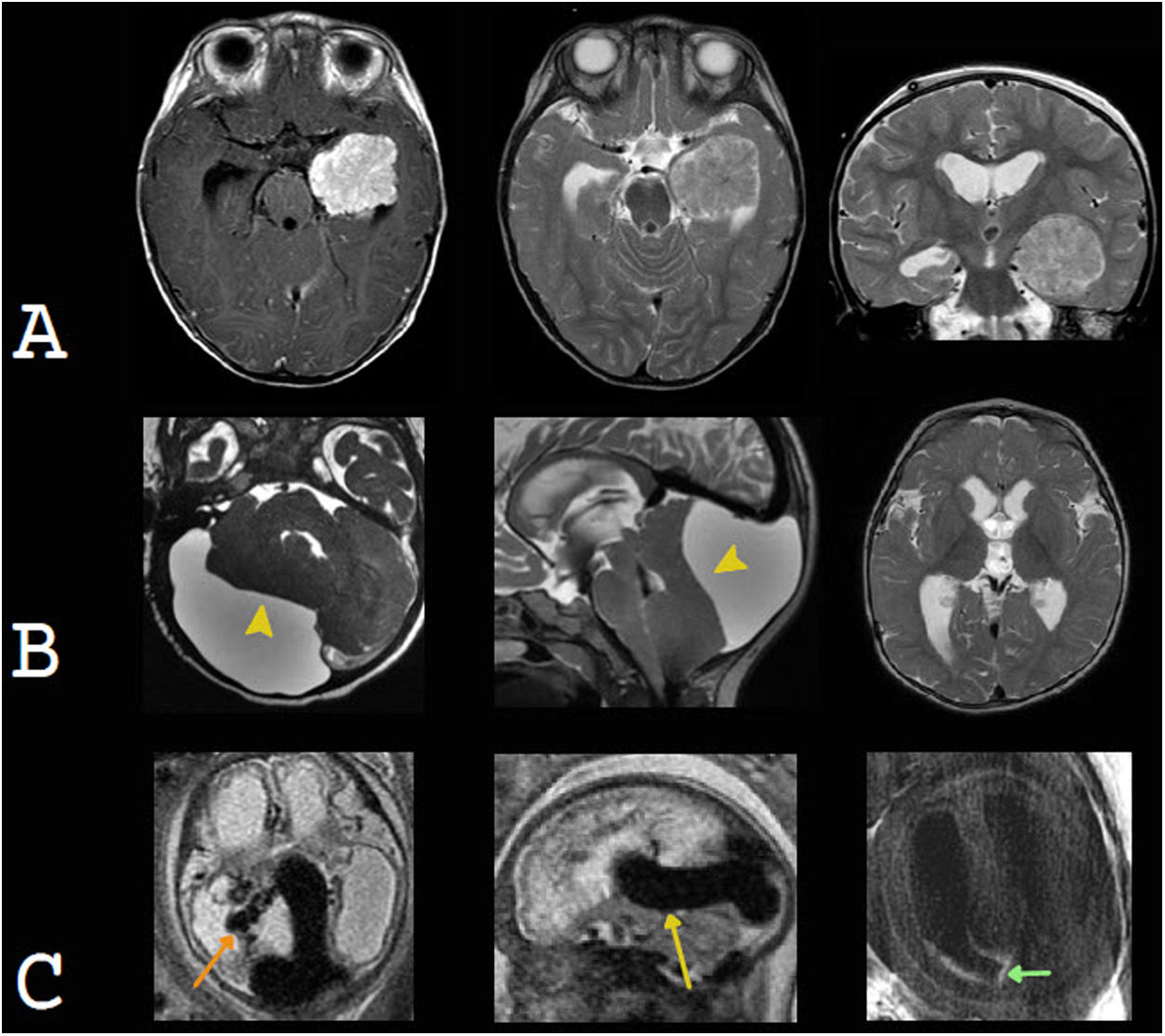

Expansive conditionsJust 5%–10% of brain tumours present with macrocephaly. If children under four years of age alone are considered, this percentage increases to 41%,45 but, in general, it is uncommon for macrocephaly to present as an isolated symptom. Tumours manifest primarily with signs of intracranial hypertension, especially of the midline and posterior fossa, and other neurological abnormalities.10,20

Exceptions are desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma (DIA) and desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma (DIG), which, due to their near-invariably supratentorial location and non-aggressive nature, reach large volumes, resulting in an increase in HC, which in some cases is the only clinical sign.15 These are uncommon, low-grade glioneuronal tumours that primarily affect infants. They present as a usually frontal and parietal, large-volume, solid-cystic cortical lesion, whose solid component is peripheral and heterogeneous and exhibits contrast uptake and enhancement, often with leptopachymeningeal extension. Oedema is usually limited or absent.46

While uncommon, choroid plexus tumours may also manifest clinically as macrocephaly secondary to hydrocephalus, either resulting from overproduction of CSF or an abnormality in CSF reabsorption or due to a mass effect of the tumour and obstruction of CSF flow. They are classified as choroid plexus papillomas (CPPs), grade I or II, or as choroid plexus carcinomas (CPCs), grade III, according to the World Health Organization. They present as an intraventricular mass, usually in the atrium, with avid, homogeneous enhancement. They may show fluid voids due to hypervascularisation and punctiform foci of calcification or bleeding.46,47 CPCs are usually more heterogeneous, with central necrosis, bleeding and invasion of the adjacent brain parenchyma, rimmed with oedema, and more commonly show leptomeningeal dissemination. However, in most cases, they are radiologically indistinguishable from CPPs10 (Fig. 8).

Examples of intracranial expansive conditions that may present with macrocephaly. A) Choroid plexus papilloma. An intraventricular neoplastic lesion is seen in the left temporal horn. It is slightly heterogeneous and exhibits avid enhancement with contrast. It causes communicating hydrocephalus due to overproduction and lower reabsorption of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Courtesy of Dr Francisco Sepúlveda, Santiago. B) Arachnoid cyst in the posterior fossa. Formation of a voluminous cyst is identified. This cyst shows the same signal as the CSF, expands and remodels the adjacent cranial vault, compresses the cerebellar parenchyma (yellow arrow tip) and obstructs the flow of CSF at the foramen magnum and fourth ventricle, resulting in supratentorial hydrocephalus. C) Vein of Galen aneurysmal malformation. A prominent median prosencephalic vein (yellow arrow) is seen compressing the cerebral aqueduct and causing supratentorial obstructive hydrocephalus. Tortuous choroidal arteries (orange arrow) are characteristic. Intraventricular blood remnants are also seen; these could also contribute to hydrocephalus (green arrow).

Less commonly, macrocephaly may be secondary to a compression effect and resulting hydrocephalus of vascular abnormalities, such as a vein of Galen aneurysmal malformation. This abnormality is characterised by an arteriovenous shunt, in which the choroid arteries supply a persistent embryonic vein, a precursor to the vein of Galen, known as a median prosencephalic vein. This structure causes hydrocephalus as it compresses the cerebral aqueduct.48

Arachnoid cysts correspond to congenital lesions consisting of a subarachnoid membrane, whose contents maintain a similar echogenicity, signal and density to CSF. On occasion, they may compress the ventricular system, especially when they are subtentorial, or they may be giant and cause macrocephaly.49

MegalencephaliesMegalencephalies correspond to a larger brain parenchyma volume and may be benign (familial), dysplastic, developmental, or metabolic.50

Benign familial megalencephaly refers to children who have an abnormally large HC. Usually this characteristic is also present in at least one of their parents. It is not associated with neurological abnormalities, and it shows no radiological signs.51

Developmental megalencephalies are secondary to abnormalities in cell proliferation pathways; the most common among them are the mTOR and Ras/MAPK pathways, affecting either cell replication or apoptosis, leading to an increase in the number and/or size of the neurons. Patients present macrocephaly at birth, which continues to increase in their growth curve. Examples of developmental megalencephalies due to impairment of the mTOR pathway include tuberous sclerosis and classic hemimegalencephaly. Among abnormalities due to impairment of the Ras/MAPK pathway (Rasopathies), the most common is NF1.52

Tuberous sclerosis complex is a neurocutaneous abnormality secondary to mutation of the TSC1 and TSC2 cell proliferation suppressor genes. Macrocephaly is due primarily to megalencephaly, but hydrocephalus may also be added due to obstruction of the foramina of Monro, to subependymal nodules or to the development of subependymal giant-cell astrocytomas (SEGAs). Radial migration bands and cortical tubers are characteristic of this entity53,54 (Fig. 9).

Examples of developmental megalencephaly. In this disease group, radiological findings are asymmetrical. A) Neurofibromatosis type 1. High-signal foci in T2 (FOCI) in the right globus pallidus and cerebral peduncle (yellow and green arrow tips, respectively). Thickening of the right optic nerve, without contrast enhancement, consistent with an optic pathway glioma, is also observed (orange arrow). B) Dysplastic complete unilateral hemimegalencephaly. Enlarged right cerebral hemisphere and lateral ventricle. Extensive abnormalities of cortical development are also seen (green arrow tip), with subependymal heterotopic nodules (yellow arrow tip). C) Tuberous sclerosis. In the T2-FLAIR sequence, cortical tubers (orange arrow) and characteristic radial migration bands (green arrow) are observed. In the contrast-enhanced T1-weighted sequence, small, non-obstructive subependymal nodules (yellow arrow tips) are seen.

Complete unilateral megalencephaly, which affects an entire cerebral hemisphere, corresponds to the classic definition of hemimegalencephaly. At present, it is recognised as a spectrum of disorders of hamartomatous overgrowth of all or part of one or both cerebral hemispheres. They may be associated with cortical malformations, in which case, they are called dysplastic megalencephaly, or with white-matter abnormalities, abnormalities of midline structures or subtentorial compromise.

NF1 is the most common phakomatosis. It is caused by mutation of the NF1 gene, which codes neurofibromin, involved in suppression of cell and/or tumour proliferation. Some 20%–45% of patients have macrocephaly, which is essentially secondary to megalencephaly.55 Foci of signal abnormality in the basal ganglia, internal capsules, brainstem and cerebellum are characteristic; they usually present before three years of age and remit during adolescence.56 These patients may develop optic nerve gliomas, usually before nine years of age, or, less commonly, gliomas in other locations.57

Metabolic megalencephalies are secondary to inborn errors of metabolism and are characterised by abnormal deposits of metabolites in the brain parenchyma. Unlike in developmental megalencephalies, abnormalities are generally symmetrical and children are born with a normal HC, but develop macrocephaly during their first few years of life. They may be classified according to the metabolic pathway affected in organic acidurias, such as GA1; lysosomal abnormalities, such as mucopolysaccharidosis; and leukoencephalopathies that present macrocephaly, such as Canavan disease, Alexander disease and megalencephalic leukoencephalopathy with subcortical cysts.50

Mucopolysaccharidosis causes multisystem accumulation of glycosaminoglycans (GSGs) in the lysosomes of different tissues. Macrocephaly occurs both due to megalencephaly secondary to GSG deposition in the brain parenchyma and due to hydrocephalus caused by GSG deposition in the meninges, with lower CSF absorption. Other radiological findings are dilation of the perivascular spaces, with predominantly periventricular white-matter abnormalities and cortical atrophy, as well as odontoid dysplasia, with atlantoaxial instability and stenosis of the spine and medulla oblongata.58,59

Alexander disease is a type of leukodystrophy caused by mutation of the GFAP gene, and the phenotype that it expresses depending on the type of mutation. The neonatal subtype of this disease classically presents with compromise of the white matter (predominantly frontal) and basal ganglia and periventricular abnormality hyperintense on T1-weighted sequences60,61 (Fig. 10).

Examples of metabolic megalencephaly. In this disease group, radiological findings are generally symmetrical. A) Alexander disease. An increase in the T2 signal of the predominantly frontal white matter (green arrow) and basal ganglia (green arrow tips) as well as periventricular T1 signal hyperintensity (orange arrows) are characteristic. Courtesy of Dr Felice D'Arco, London. B) Canavan disease. Imaging in T2-weighted sequences exhibits extensive white matter signal hyperintensity and abnormalities in the basal ganglia. Spectroscopy shows a significant, characteristic N-acetylaspartate peak (yellow arrow tip). Courtesy of Dr Luis Filipe de Souza Godoy, São Paulo. C) Megalencephalic leukoencephalopathy with subcortical cysts. In T2-weighted sequences, an extensive signal hyperintensity of the white matter is observed, in a diffuse and homogeneous form. Frontal subcortical cysts (not shown) and temporal subcortical cysts (white arrow) are recognised. Courtesy of Dr Felice D'Arco, London.

Canavan disease is a disorder caused by N-acetylaspartate (NAA) accumulation in the brain parenchyma. MRI findings are characteristic, with extensive changes in the white matter, featuring a centripetal pattern — that is, first the more cortical white matter is affected and then the deeper white matter is affected. Abnormalities in the subcortical grey matter may also be seen, especially in the globus pallidus and thalamus.62 Spectroscopy shows a significant, characteristic NAA peak.63,64 Macrocephaly usually occurs in children under one year of age.65

In megalencephalic leukoencephalopathy with subcortical cysts, there is a mutation in the membrane protein that regulates water flow, with accumulation of interstitial water. It presents as a diffuse, homogeneous abnormality of white matter, with subcortical cysts in the temporal poles and frontoparietal convexity. Macrocephaly is very marked (more than four to six SDs above the mean), and the discrepancy between the severity of radiological abnormalities and clinical compromise is striking.66

Thickening of the cranial vault and/or skull baseBone marrow expansion, as in anaemia with rapid haematopoiesis, or skeletal dysplasias such as achondroplasia or osteopetrosis, can lead to an increase in HC.

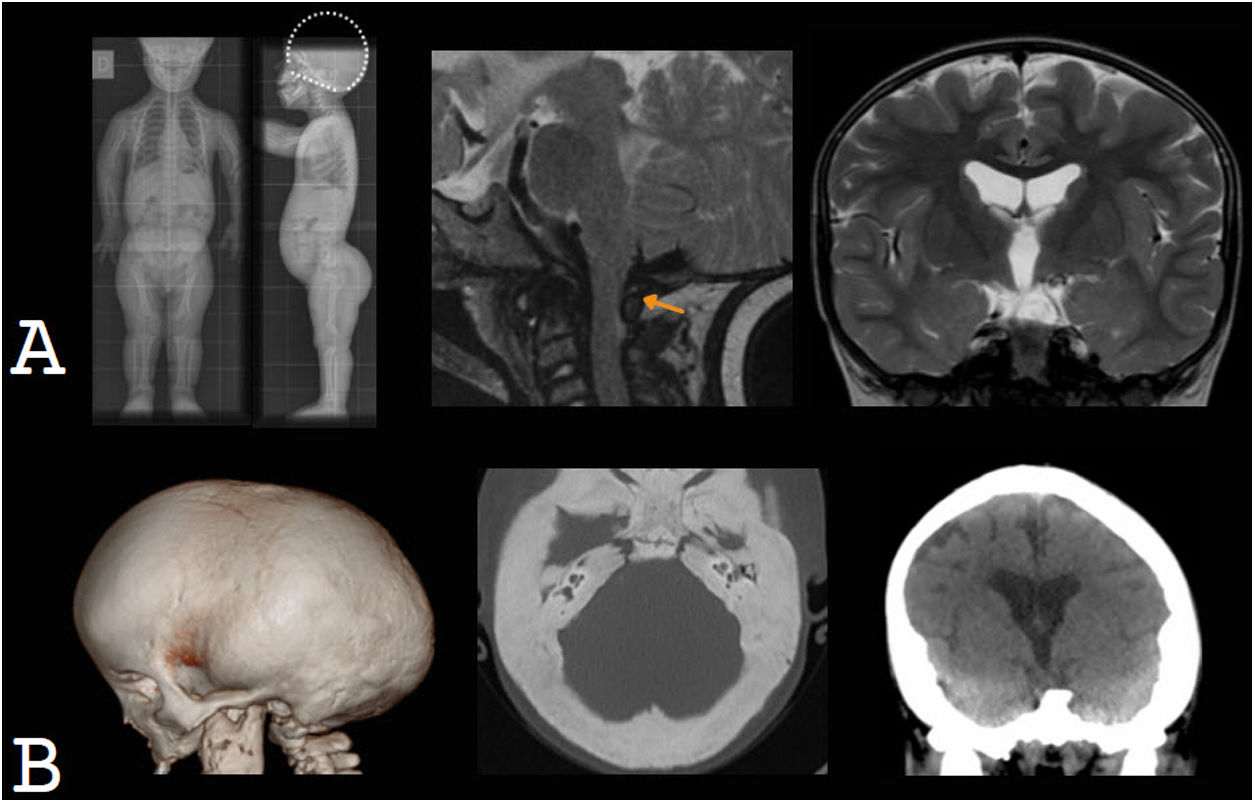

Children with achondroplasia present marked macrocephaly at birth, which progresses during the first year of life and is of multifactorial origin (Fig. 11). On the one hand, there is megalencephaly, possibly due to the direct effect of a fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR3); on the other hand, the foramen magnum and the jugular foramina are small. The latter may obstruct CSF flow and venous drainage, resulting in the onset of hydrocephalus, which contributes to the increase in HC.67,68

Skeletal dysplasias as a cause of macrocephaly. A) Achondroplasia. Plain X-ray of the entire body showing marked macrocephaly, with no skull-base compromise. Sagittal T2-weighted MRI shows that the foramen magnum is small and obstructs the flow of cerebrospinal fluid, contributing to hydrocephalus, which is mild. B) Osteopetrosis. Marked thickening of the cranial vault and skull base and moderate hydrocephalus are observed.

Osteopetrosis is a skeletal dysplasia that causes thickening and sclerosis of the cranial vault, skull base and facial bones. The most aggressive form is autosomal recessive or malignant infantile osteopetrosis.69 The thickening of the skull base leads to a reduction in the size of the foramen magnum and subsequent tearing, which can cause hydrocephalus. Enlargement of the cranial vault and hydrocephalus are involved in the development of macrocephaly, which is often mild.70,71

ConclusionMacrocephaly occurs when there is an increase in intracranial volume, provided that this happens before the cranial sutures close, gradually, allowing the skull to expand. A rapid increase in intracranial cavity volume presents as intracranial hypertension, without macrocephaly.

The main causes of macrocephaly are benign familial megalencephaly and benign enlargement of the subarachnoid space; these are non-pathological entities. Less commonly, macrocephaly is an expected component of clinical syndromes. Neuroradiology studies are aimed at identifying children with macrocephaly who have disease that requires timely clinical/surgical management, such as hydrocephalus, subdural collections and expansive conditions.

Patients with macrocephaly and risk factors such as neurological abnormalities, neurocutaneous stigmata, developmental delays or a rapid increase in HC require study with MRI or CT. Patients without risk factors who have a parental history of macrocephaly require no radiological study; however, in the absence thereof, we suggest an initial ultrasound study. Limiting radiological study to these patients and using the appropriate radiological technique optimises resource use and reduces tests involving unnecessary radiation exposure.

Authorship- 1

Responsible for study integrity: VSG

- 2

Study concept: VSG

- 3

Study design: VSG

- 4

Data collection: not applicable

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: not applicable

- 6

Statistical processing: not applicable

- 7

Literature search: VSG

- 8

Drafting of the article: VSG

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: AR

- 10

Approval of the final version: LHR

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Valeria Schonstedt G. would like to thank Dr Georg Schonstedt R. for his invaluable support in the preparation of this manuscript.

Please cite this article as: Schonstedt Geldres V, Stecher Guzmán X, Manterola Mordojovich C, Rovira À. Radiología en el estudio de la macrocefalia. ¿Por qué?, ¿cuándo?, ¿cómo? Radiología. 2022;64:26–40.