The choice of imaging techniques in the diagnosis of acute diverticulitis is controversial. This study aimed to determine radiologists’ preferences for different imaging techniques in the management of acute diverticulitis and the extent to which they use the different radiologic techniques for this purpose.

MethodsAn online survey was disseminated through the Spanish Society of Abdominal Imaging (Sociedad Española de Diagnóstico por Imagen del Abdomen (SEDIA)) and Twitter. The survey included questions about respondents’ working environments, protocolization, personal preferences, and actual practice in the radiological management of acute diverticulitis.

ResultsA total of 186 responses were obtained, 72% from radiologists working in departments organized by organ/systems. Protocols for managing acute diverticulitis were in force in 48% of departments. Ultrasonography was the initial imaging technique in 47.5%, and 73% of the respondents considered that ultrasonography should be the first-choice technique; however, in practice, ultrasonography was the initial imaging technique in only 24% of departments. Computed tomography was the first imaging technique in 32.8% of departments, and its use was significantly more common outside normal working hours. The most frequently employed classification was the Hinchey classification (75%). Nearly all (96%) respondents expressed a desire for a consensus within the specialty about using the same classification. Hospitals with >500 beds and those organized by organ/systems had higher rates of protocolization, use of classifications, and belief that ultrasonography is the best first-line imaging technique.

ConclusionsThe radiologic management of acute diverticulitis varies widely, with differences in the protocols used, radiologists’ opinions, and actual clinical practice.

La elección de las técnicas de imagen en el diagnóstico de la diverticulitis aguda (DA) es un motivo de controversia. Los objetivos del estudio fueron conocer las preferencias de los radiólogos y el grado de utilización de las distintas técnicas en su manejo radiológico.

MétodosSe difundió una encuesta por Internet a través de la Sociedad Española de Diagnóstico por Imagen del Abdomen (SEDIA) y Twitter, con preguntas sobre ámbito de trabajo, protocolización, preferencias personales y la realidad asistencial en el manejo radiológico de la DA.

ResultadosSe obtuvieron 186 respuestas. El 72% de los radiólogos encuestados trabaja en servicios organizados por «órgano y sistema» (S-OS). Existe protocolo de manejo de DA en un el 48% de los servicios, siendo en el 47,5% la ecografía la técnica de inicio. El 73% de los encuestados cree que la ecografía debería ser la primera opción diagnóstica, pero en realidad esto solo se efectúa en un 24% de los servicios, realizándose tomografía computarizada en el 32,8%, con diferencias significativas en horario de guardia. La clasificación más utilizada es la de Hinchey (75%). El 96% de los encuestados desearía un consenso de especialidad para utilizar la misma clasificación. Existe mayor tasa de protocolización, utilización de clasificaciones y mayor creencia en la ecografía como técnica inicial en S-OS y en hospitales con más de 500 camas.

ConclusionesHay una gran variabilidad en el manejo radiológico de la DA, con divergencias en los protocolos utilizados y entre las opiniones de los radiólogos y la práctica clínica real.

Acute diverticulitis (AD) is one of the most common causes for consultation due to abdominal pain in Emergency departments1 and the therapeutic management of this disease differs greatly based on the severity of its presentation.2 AD primarily affects people of advanced age, but its incidence in young patients is increasing. It is a disease with nonspecific clinical manifestations, so it requires an imaging test to establish the diagnosis with certainty, as well as its degree of severity. There is ongoing controversy about the most appropriate diagnostic technique,3 despite the apparent lack of significant differences between the efficacy of computed tomography (CT) and ultrasound for diagnosing it.4 The recommendations on the use of one technique or another for the initial diagnosis of AD are variable according to the different clinical guidelines and consensus documents consulted,5 and multiple classifications are also available to stage its severity, without the existence of a consensus regarding their use, either.6

The objective of this project is to analyse the opinion of Spanish radiologists who are members of the Sociedad de Diagnóstico de Imagen Abdominal (SEDIA) about different aspects of the radiological management of AD in Spain and to compare it with the usual practice in their department.

Material and methodsA digital survey disseminated via the Internet was designed (https://es.surveymonkey.com/r/CFRRCYQ) with 24 questions about the work environment, hospital size, possibility of organisation of the department by organ and system (D-OS) and the different options for radiological management of the AD. It also asked about the management based on working hours (assuming a standard daytime schedule), the radiologists' specialisation and the hospitals' different night shift models, as well as the existence of protocols for the study of AD and, in this case, the imaging technique of choice. When they opted for CT as the initial technique for the diagnosis of AD, it asked about the reasons why they used it. With regard to ultrasound, it asked about the degree of use as an initial technique, the opinion of those surveyed on its utility in the study of AD and their opinion on the quality of radiologists’ training in ultrasound of AD. Ultrasound with contrast was assessed (opinion on its utility and habitual use). Other questions were asked about the use of the prognostic classifications of AD and their utility for managing this pathology, as well as the need to modify them or to reach a consensus on their use.

The questionnaires were designed by a team with previous experience conducting surveys and were submitted for evaluation by a small number of experts belonging to the society involved. Simple and impartial direct questions were drafted, without ambiguities, trying to avoid directed questions. The majority were structured questions that covered all the possible alternatives, making sure that each response was unique. Several questions included general answers (like “others”) to guarantee the effective collection of the potential diversity of answers. Some questions allowed for multiple answers, and others, an optional response not listed in the predefined options (Table 1).

Survey questions.

| 1. Work environment |

| Public hospital |

| Private hospital |

| 2. Size of the hospital where you work |

| <250 beds |

| Between 250 and 500 beds |

| >500 beds |

| 3. Is the Diagnostic Imaging department where you work organised by "organ and system"? |

| Yes |

| No |

| 4. During working hours, who performs the urgent abdominal examinations? |

| Abdominal radiologists |

| General radiologists |

| Radiologists specialised in emergency care |

| 5. During working hours, the technique used for the initial diagnosis of AD is: |

| Always starts with ultrasound |

| Always starts with CT |

| Ultrasound vs. CT based on the radiologist |

| Ultrasound vs. CT based on the clinical severity |

| 6. Outside of working hours, is there a 24-h in-person radiologist on the night shift? |

| Yes |

| No |

| 7. If no, who is responsible for the radiological emergencies at your hospital outside of the radiologists' working hours? |

| In-person radiologists until a certain time and then teleradiology |

| Teleradiology from the end of working hours |

| Others (specify) |

| 8. If there is an in-person radiologist on the night shift, what technique is used for the initial diagnosis of the AD? |

| Always starts with CT |

| Always starts with ultrasound |

| One technique or another based on the radiologist who is on the night shift |

| One technique or another based on the severity of the patient |

| 9. At your hospital, is there a protocol for the diagnosis of AD? |

| Yes |

| No |

| 10. If yes, what is the protocol? |

| Always CT to start |

| Ultrasound to start and CT for undiagnosed, confusing or severe cases |

| Others (specify) |

| 11. Are residents trained in your department? |

| Yes |

| No |

| 12. If no, do you believe that your residents leave well-trained to make a diagnosis of AD via ultrasound? |

| Yes |

| No |

| 13. Indicate the degree of agreement with the following statement: "ultrasound is the technique of choice for the initial diagnosis of AD and CT must be reserved for complicated cases, inconclusive ultrasounds and diagnostic doubts" |

| 14. Do you think that ultrasound with contrast can be useful in the diagnosis or monitoring of AD? |

| Yes, both in the initial diagnosis and in the monitoring of the therapeutic response |

| Yes, only in the monitoring of the therapeutic response |

| No, I do not think it can provide additional information for making decisions |

| Other (specify) |

| 15. Do you routinely use ultrasound with contrast in your habitual practice for assessment of the severity of the AD? |

| Yes |

| No |

| Sometimes |

| Others (specify) |

| 16. Why do you think CT is used at many centres as an initial technique for the diagnosis of AD when done within working hours? Accepts multiple responses |

| Lack of experience of abdominal radiologists in ultrasound of AD |

| Lack of “organ and system” specialisation in your department |

| Lack of sufficient knowledge on the issue |

| The findings from CT of AD require less experience to be reported |

| Others (specify) |

| 17. Why do you think CT is used as an initial technique for the diagnosis of AD when done outside working hours? Accepts multiple responses |

| Lack of experience of the radiologist on the night shift (even if they are abdominal) |

| Night shift undertaken by general radiologists |

| Night shift performed by radiologists from an "organ and system" other than the abdomen |

| Teleradiology |

| Others (specify) |

| 18. Do you agree that abdominal radiologists and general radiologists should be trained in ultrasound of AD? |

| Yes |

| No |

| 19. At your hospital, do they use any classification to determine the severity of the AD regardless of the technique used to diagnose it? |

| Yes |

| No |

| 20. If yes, which of the following classifications do they use? |

| Hinchey Classification |

| Neff Classification |

| Modified Neff Classification |

| Minnesota Classification |

| Other (specify) |

| 21. Do you think that the current classifications are useful in order to make treatment decisions? Allows for multiple answers |

| Yes, they are sufficient |

| No, they are based on surgical findings |

| No, the ones that are based on imaging are only based on CT findings |

| No, they do not consider all imaging findings |

| No, there is too much variability in the grading of the severity of the AD according to the classification used |

| Other (specify) |

| 22. At your hospital, is there is agreement between radiologists and surgeons about the classification to be used to determine the severity of the AD? |

| Yes |

| No |

| 23. Do you believe that an exclusive classification for ultrasound findings should exist? |

| Yes, since the ultrasound has greater sensitivity than the CT to detect inflammatory changes of mild AD on the colon wall in the absence of peridiverticular or pericolonic phlegmon (hypoechogenicity, mural hypervascularisation, etc.) |

| No, since the findings of the CT and of the ultrasound are the same and both tests show an equal sensitivity in mild or complicated AD |

| No, if a classification capable of encompassing all the findings, both ultrasound and CT, were created |

| Other (specify) |

| 24. Since different degrees of the severity of the AD exist according to the classification used, do you believe that a consensus to use the same classification should exist? |

| Yes, the degree of severity should not vary based on the classification used |

| No, all the classifications allow for reliably grading the AD and making appropriate treatment decisions |

| Other (specify) |

AD: acute diverticulitis; CT: computed tomography.

The survey was distributed to SEDIA members via email. The survey link was also disseminated through Twitter. The invitation to the survey was kept open for two months.

The answers were entered into a computer database that was analysed via the programme SPSS (v. 10.0, Chicago, IL., USA). The description of the survey results was expressed as percentages of the total responses obtained. The statistical analysis of the data was done by means of Pearson's chi-squared test. The statistical significance of p < 0.05 was accepted.

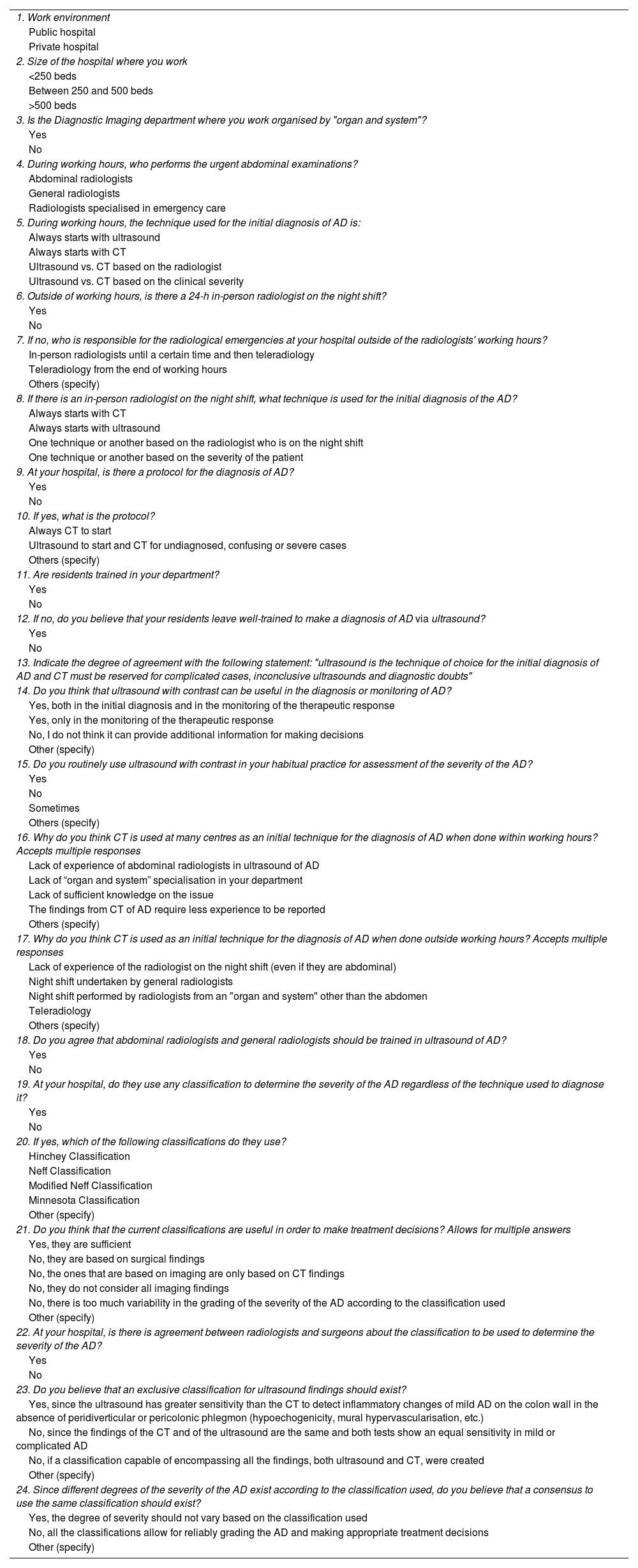

ResultsGeneral resultsWe received 186 responses. Table 2 shows a summary of the general results. 18.8% of those surveyed work in hospitals [with] <250 beds, 36.6% with 250–500 beds and 44,6% [with] >500 beds. 72.4% of those surveyed work in D-OS.

Summary of the general results of the survey.

| Work environment | Public | Private |

|---|---|---|

| 89.2% | 10.8% | |

| Organisation by "organ and system" | Yes | No |

| 72.4% | 27.6% | |

| 24-h in-person radiologist | Yes | No |

| 81.2% | 18.8% | |

| Abdominal emergencies without an in-person radiologist on the night shift | Radiologist/teleradiology | Teleradiology |

| 41% | 36% | |

| Existence of protocol | Yes | No |

| 48.4% | 51.6% | |

| Protocol | Initial CT | Initial ultrasound |

| 39.6% | 47.5% | |

| Training of residents | Yes | No |

| 74% | 26% | |

| The Resident Medical Interns are well trained in ultrasound of AD | Yes | No |

| 57.5% | 42.5% | |

| Abdominal radiologists and general radiologists should be trained in ultrasound of AD | Yes | No |

| 92.5% | 7.5% | |

| Utility of ultrasound with contrast | Useful in diagnostics or monitoring | Not useful |

| 31.1% | 51.4% | |

| Ultrasound with contrast used | Yes | No |

| 0.5% | 92.4% | |

| Use of classifications | Yes | No |

| 67.2% | 32.8% | |

| The current classifications are useful in order to make treatment decisions | Yes | No |

| 46.8% | 64.8% | |

| In your hospital there is an agreement between radiologists and surgeons about the classification to be used | Yes | No |

| 47.3% | 52.7% | |

| An exclusive classification for ultrasound findings should exist | Yes | No |

| 31.6% | 62.7% | |

| There should be a consensus to use the same classification | Yes | No |

| 95.7% | 2.7% |

AD: acute diverticulitis; MIR: resident medical intern.

Emergency abdominal examinations are performed during working hours by members of the abdomen section in 33.3% of cases, by general radiologists in 37.1% and by radiologists specialised in emergency care in 29.6%.

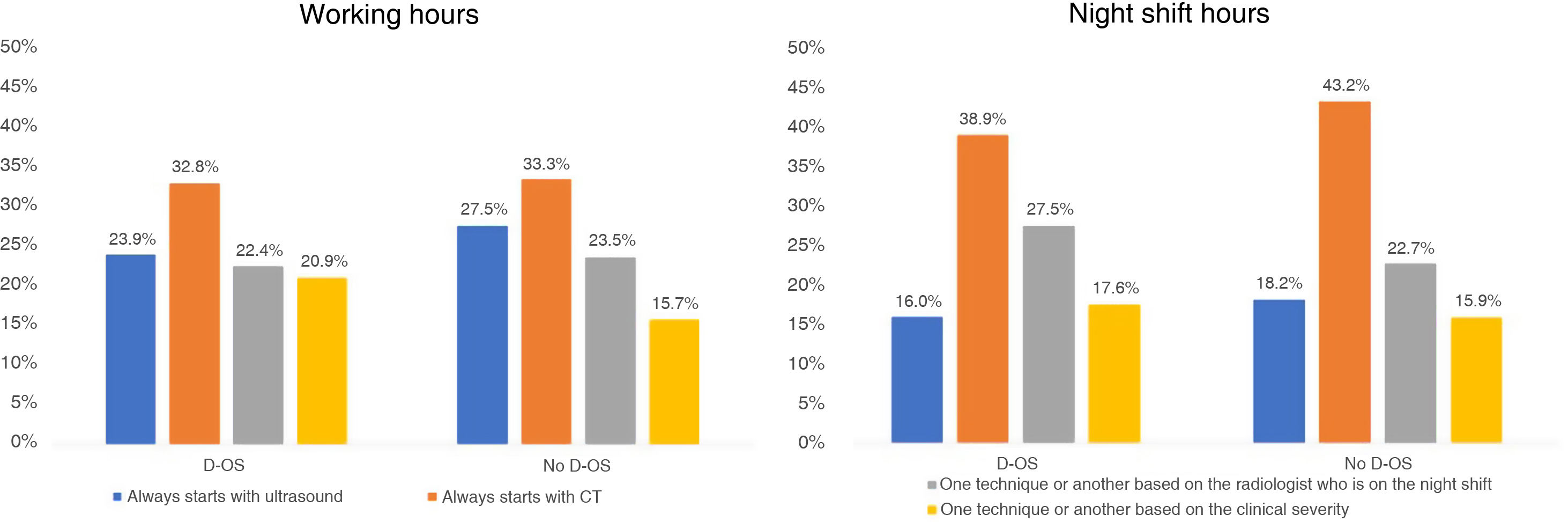

During working hours, the initial technique to study suspected AD is ultrasound in 24.7% of departments and CT in 32.8%. In the rest of the departments, the technique can be chosen according to the radiologist's preference (22.6%) or based on the clinical severity of the AD episode (19.9%). In the situation of the night shift with an in-person radiologist, the initial technique is ultrasound in 16.5% of hospitals, CT in 39.8%, and it is chosen according to the radiologist or clinical severity in 26.7% and 17.1%, respectively.

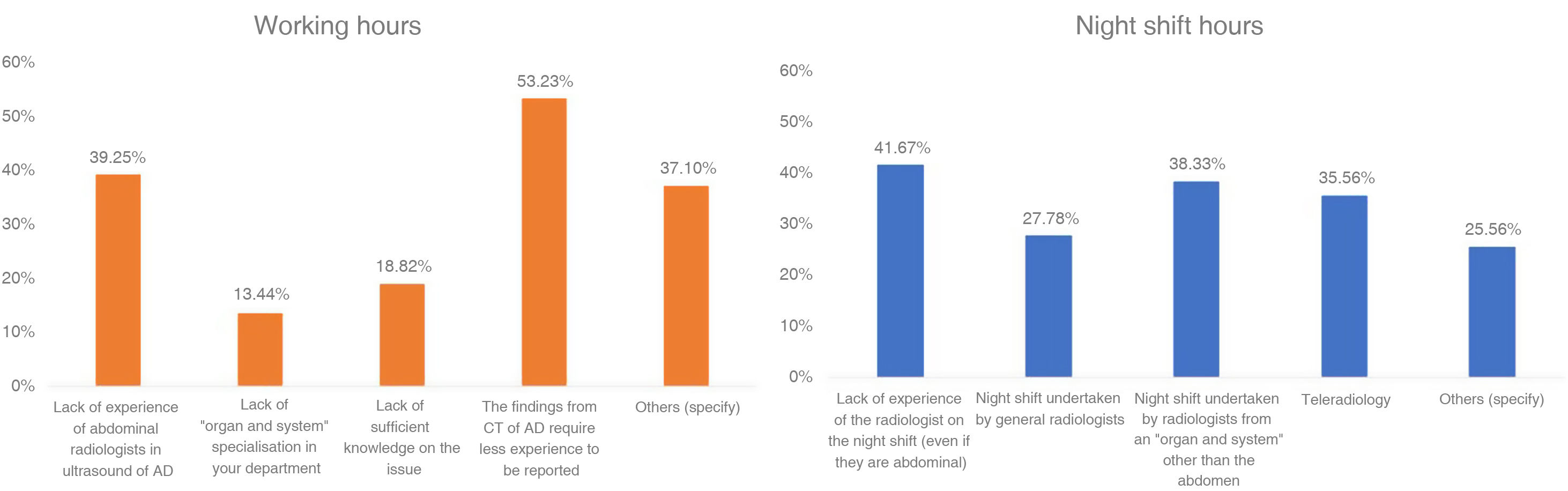

The reasons for the use of CT as the initial technique for the diagnosis of AD both during and outside of working hours are reflected in Fig. 1.

The degree of agreement with the statement “Ultrasound is the technique of choice for the initial diagnosis of AD and CT must be reserved for complicated cases, inconclusive ultrasounds and diagnostic doubts” is 73%, while 92.5% of the radiologists state that both general radiologists and abdominal radiologists must be trained in ultrasound for the diagnosis of AD. Only 57.5% of those surveyed think that the radiodiagnostic training of the resident medical interns (MIR) in ultrasound for AD is adequate.

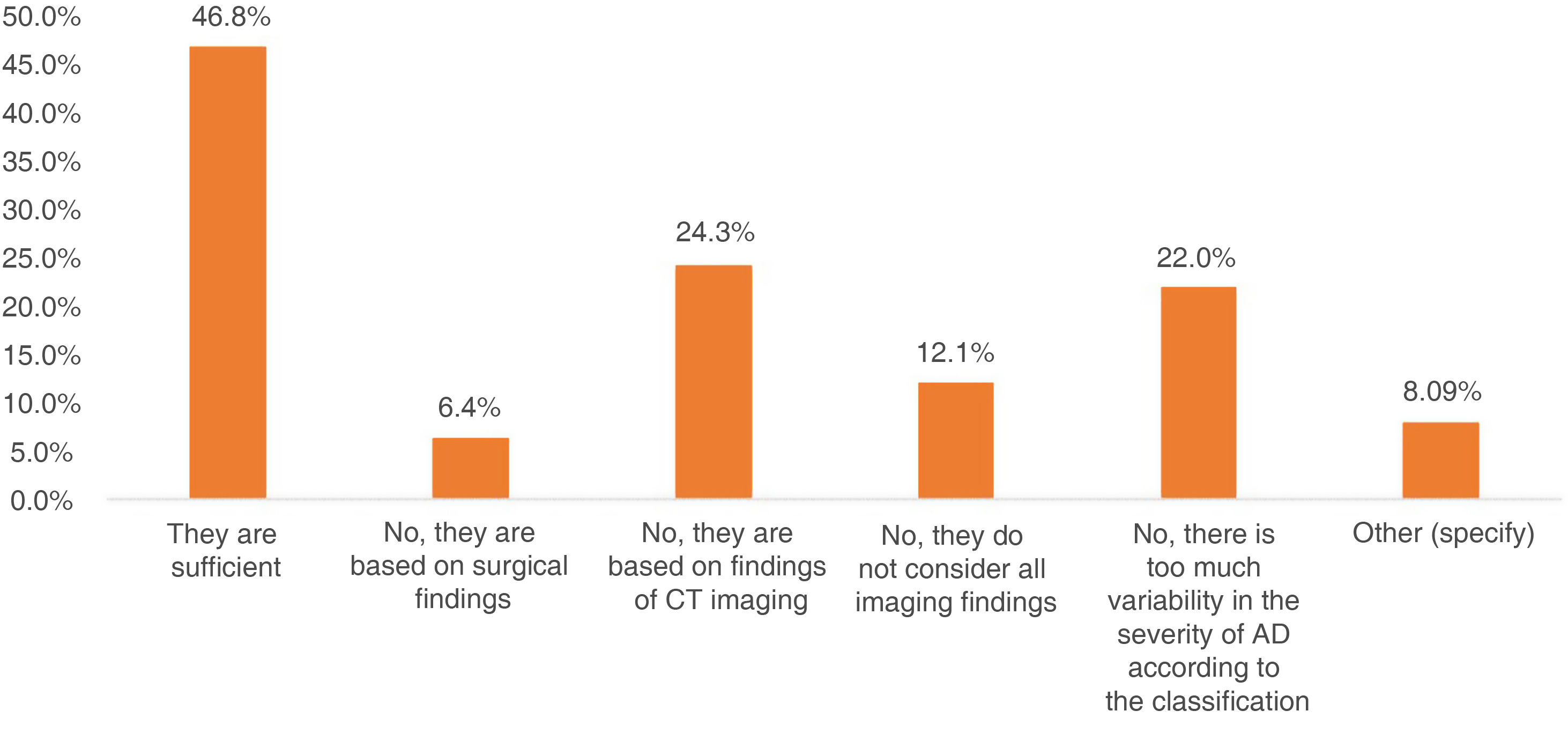

The prognostic classification used most is Hinchey et al.7 (Fig. 2). 64.8% of the radiologists believe that the current classifications are not sufficient to make treatment decisions (Fig. 3) and 95.7% advocate for an agreement between radiologists to use the same classification.

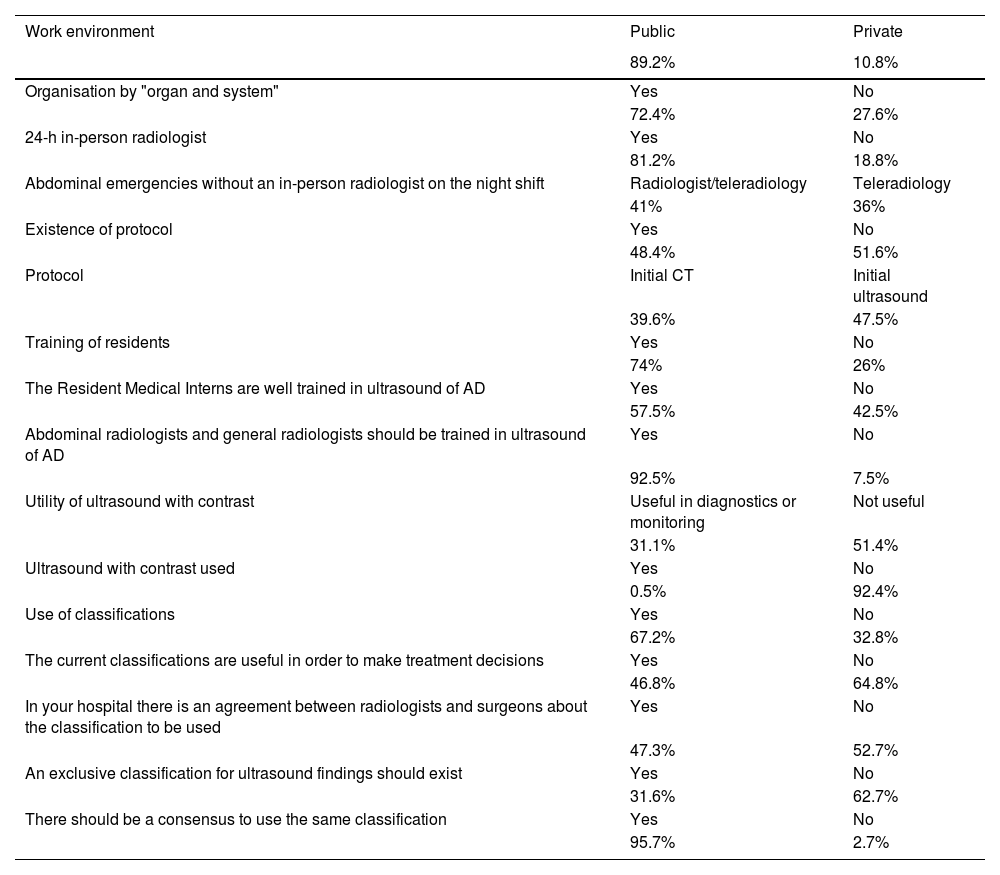

The public hospital departments are D-OS in 77% of cases, while they are 35% in private hospitals. Table 3 shows some of the results compared according to the existence of this type of organisation or not.

Comparison of results based on the organisation of the department by "organ and system".

| Yes (D-OS) | No (D-OS) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24-h in-person radiologist | 89.6% | 58.8% | <0.05 |

| A radiological protocol for AD exists | 57.0% | 25.5% | <0.05 |

| Protocol: CT to start | 40.5% | 41.7% | NS |

| Protocol: ultrasound to start | 44.9% | 58.3% | NS |

| Training Resident Medical Intern | 84.4% | 45.1% | <0.05 |

| Proper training of Resident Medical Interns in ultrasound of AD | 60.9% | 41.7% | NS |

| Ultrasound with contrast is useful | 26.1% | 26.5% | NS |

| Use of ultrasound with contrast | 0.7% | 0% | NS |

| Radiologists must be trained in ultrasound of AD | 91.9% | 94.1% | NS |

| Use any classification of AD | 75.6% | 43.14% | <0.05 |

| The current classifications are useful | 52.4% | 34.7% | NS |

| Agreement between radiologists/surgeons about the classification | 55.3% | 26.0% | <0.05 |

| An ultrasound classification for AD is necessary | 33.1% | 29.8% | NS |

AD: acute diverticulitis; MIR: resident medical intern; ns: not statistically significant; CT: computed tomography; D-OS: “organ and system” organisation.

The D-OS have greater percentages of in-person night shift [staff], of resident medical intern training, of use of classifications for AD and of protocols for management of AD, but there are no differences regarding the classification used most (mostly Hinchey, followed by modified Neff [version]8) nor on the recommended examination to start (CT or ultrasound).

There are also differences favouring the D-OS in the degree of agreement between radiologists and surgeons with respect to the classification to be used (55.3% vs. 26%).

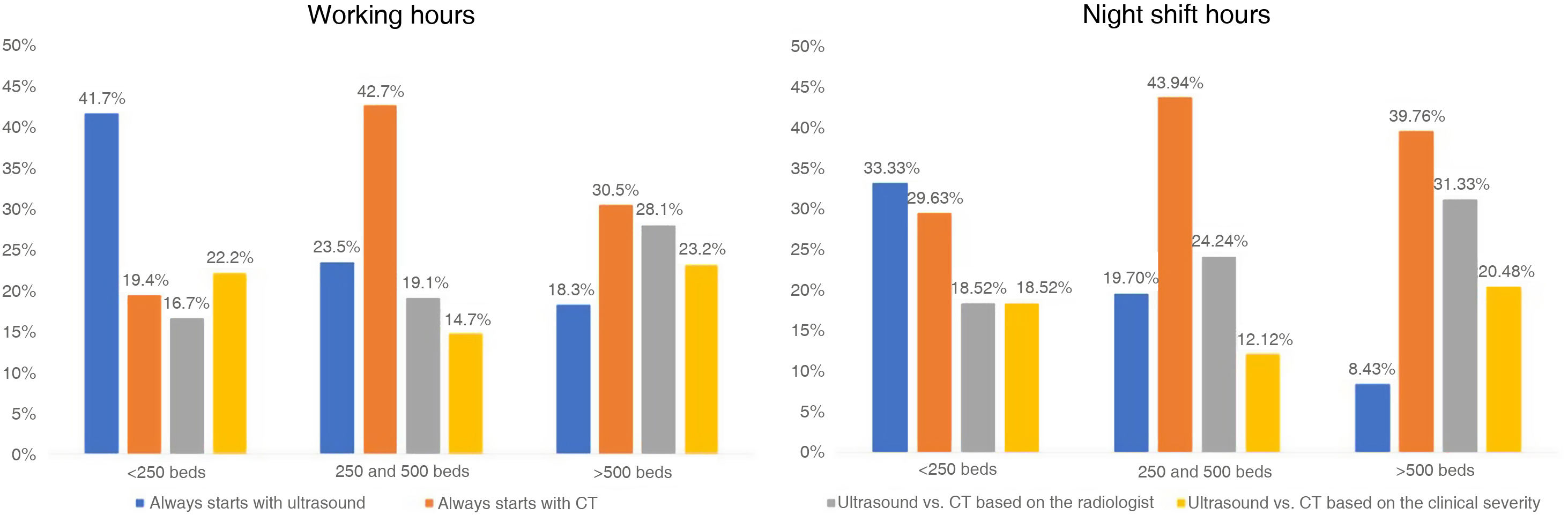

Fig. 4 shows the use of ultrasound and of CT in working hours and night shift hours with an in-person radiologist, both in D-OS and non-D-OS [departments].

Use of ultrasound and CT in the diagnosis of AD. Frequency of the different options in the use of ultrasound and CT for the initial diagnosis of AD, according to whether it is done during working hours or not and according to whether the hospital is organised by “organ and system” or not.

CT: computed tomography; D-OS: organ and system.

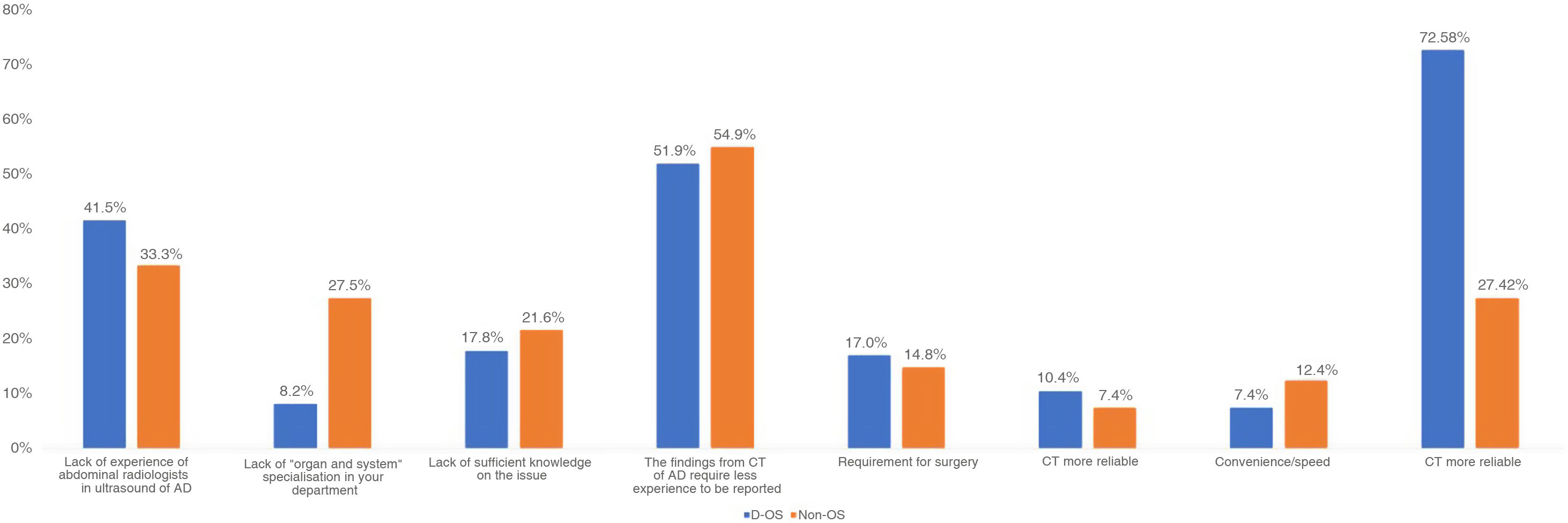

The reasons why CT was used as an initial technique for the diagnosis of AD during working hours are described in Fig. 5. During the night shift, the reasons are similar, without significant differences between D-OS and non-D-OS. The only significant differences were a greater percentage of the presence of radiologists specialised in abdominal disease in D-OS (44.7% vs. 18.8%) and a greater percentage of teleradiology in the non-D-OS hospitals (56.3% vs. 28.03%).

Reasons for the use of CT for the initial diagnosis of acute diverticulitis during working hours according to the type of organisation. Frequency of the reasons considered by those surveyed for the use of CT in the initial diagnosis of AD during working hours, according to whether it is a hospital organised by “organs and systems” or not.

AD: acute diverticulitis; CT: computed tomography; D-OS: organ and system.

Those surveyed coming from D-OS have a higher degree of agreement with the statement on ultrasound as the technique of choice for the initial diagnosis of AD (72.8%) than those from hospitals that are not organised in this manner (27.2%).

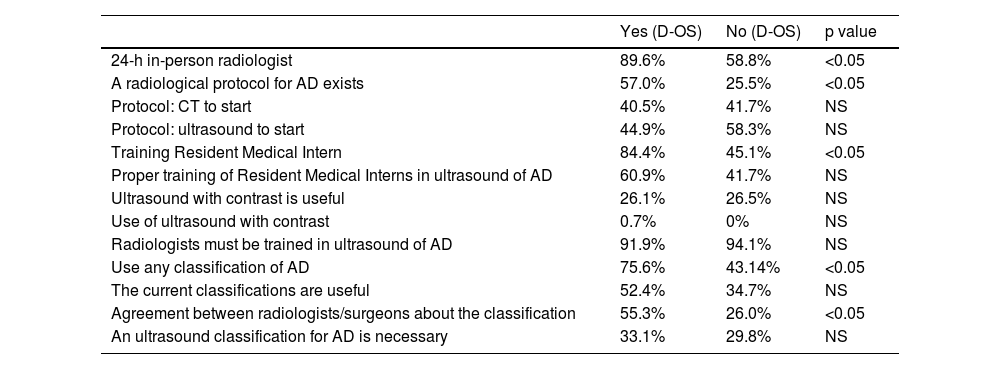

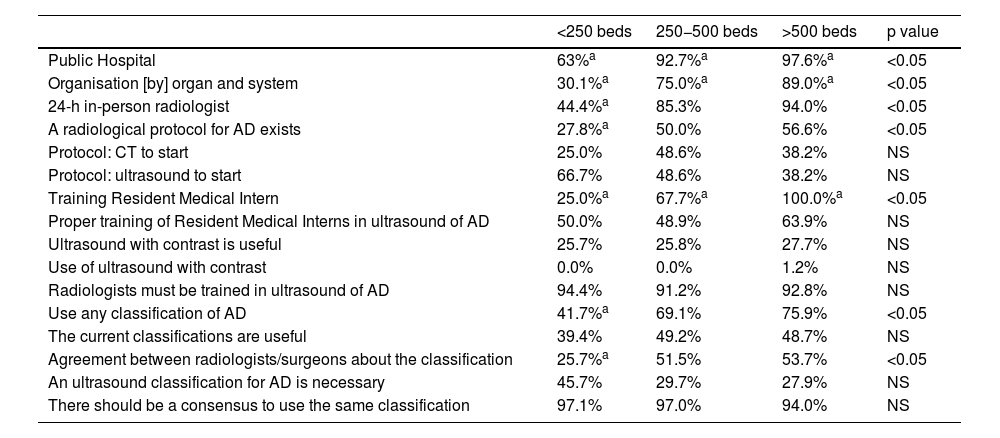

Results by hospital levels63% of hospitals with fewer than 250 beds are public, while those with 250−500 beds and more than 500 are at 92.7% and 97.6%, respectively. Table 4 shows some of the results obtained by hospital levels. In hospitals with a greater number of beds, more organisation by organ and system, a greater presence of 24-h radiologists on the night shift, a greater degree of radiological protocols for management of AD and greater use of any classification are observed. A lesser degree of agreement was also observed between radiologists and surgeons in hospitals with fewer than 250 beds.

Comparison of results according to the hospital size.

| <250 beds | 250−500 beds | >500 beds | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Hospital | 63%a | 92.7%a | 97.6%a | <0.05 |

| Organisation [by] organ and system | 30.1%a | 75.0%a | 89.0%a | <0.05 |

| 24-h in-person radiologist | 44.4%a | 85.3% | 94.0% | <0.05 |

| A radiological protocol for AD exists | 27.8%a | 50.0% | 56.6% | <0.05 |

| Protocol: CT to start | 25.0% | 48.6% | 38.2% | NS |

| Protocol: ultrasound to start | 66.7% | 48.6% | 38.2% | NS |

| Training Resident Medical Intern | 25.0%a | 67.7%a | 100.0%a | <0.05 |

| Proper training of Resident Medical Interns in ultrasound of AD | 50.0% | 48.9% | 63.9% | NS |

| Ultrasound with contrast is useful | 25.7% | 25.8% | 27.7% | NS |

| Use of ultrasound with contrast | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.2% | NS |

| Radiologists must be trained in ultrasound of AD | 94.4% | 91.2% | 92.8% | NS |

| Use any classification of AD | 41.7%a | 69.1% | 75.9% | <0.05 |

| The current classifications are useful | 39.4% | 49.2% | 48.7% | NS |

| Agreement between radiologists/surgeons about the classification | 25.7%a | 51.5% | 53.7% | <0.05 |

| An ultrasound classification for AD is necessary | 45.7% | 29.7% | 27.9% | NS |

| There should be a consensus to use the same classification | 97.1% | 97.0% | 94.0% | NS |

AD: acute diverticulitis; MIR: resident medical intern; ns: not statistically significant; CT: computed tomography.

During working hours, in the hospitals with fewer than 250 beds, emergency abdominal examinations are performed primarily by general radiologists (83.3%). In hospitals with 250−500 beds, these examinations are mostly done by radiologists specialised in abdominal disease and by general radiologists (42.7% in both cases). In hospitals with more than 500 beds they are spread between abdominal radiologists (33.7%) and radiologists specialised in emergency care (54.2%).

Outside of working hours, in-person radiologists provide emergency care on 30% of occasions in hospitals with fewer than 250 beds until a certain hour, after which teleradiology is opted for. In 50% of cases, teleradiology is done exclusively. These percentages are inverted in hospitals with 250−500 beds, where 58.3% of night shift radiologists are in person until a certain hour and then the management is through teleradiology compared to 33% where teleradiology is employed exclusively, regardless of the hour. In hospitals with more than 500 beds there is 57.1% in person and there is no use of teleradiology during night shift hours.

Fig. 6 reflects the technique used for the initial diagnosis of AD, according to the hospital size and both during working hours and night shift hours with an in-person radiologist. Regarding the reasons for the use of CT as an initial technique, there are no differences according to hospital size (Fig. 1), except with teleradiology, which represents 70% of the reasons alluded to in hospitals with fewer than 250 beds.

Technique used for the initial diagnosis of AD according to hospital size. Comparison of the technique used for the initial diagnosis of AD, both during working hours and in cases where there is an in-person radiologist on the night shift, according to the hospital size.

CT: computed tomography.

Differences are detected in the degree of agreement with the sentence on "Ultrasound as the initial technique of choice for AD", which is 34% of hospitals with fewer than 250 beds, 67% in hospitals with 250−500 beds and 83% in hospitals with more than 500 beds.

The classification used most is Hinchey et al., while modified Neff is used in 26.0% of hospitals with 250−500 beds, with statistical significance compared to those with more than 500 beds (7.9%; p < 0.05). 78.7% of radiologists in hospitals with fewer than 250 beds and 70.6% in hospitals with more than 500 beds are of the opinion that the current classifications are not sufficient for making treatment decisions, compared to 49.3% of those who work in hospitals with 250−500 beds.

DiscussionAD is an inflammatory disease that primarily affects the left colon with greater prevalence in the western world9 and it presents as mild in 75% of cases.10–12

It is a frequent cause for consultation in Emergency departments and its clinical management has changed in the last few years, given that, in mild cases, outpatient treatment is increasingly advocated for, even without administration of antibiotics.13–19

This change in clinical management, along with the presentation of the disease with symptoms that are not very specific, makes the use of imaging tests essential for confirming the diagnosis and establishing the degree of severity, as well as its prognosis. The techniques currently used for the diagnosis of acute diverticulitis of the left colon are ultrasound and CT.

In a monograph published by SERAM [Sociedad Española de Radiología Médica (Spanish Medical Radiology Society)], of literature review,5 great variability is shown in the recommendations on the technique of choice for the initial diagnosis of AD. There is a greater tendency to recommend the use of CT in countries like the US, while the European guidelines and consensuses are, in general, more in agreement with using ultrasound as the initial diagnostic technique. The sparse number of quality studies published to date is also noteworthy. Nevertheless, the authors concluded that there are no significant differences between ultrasound and CT with regard to sensitivity and specificity for the initial diagnosis of AD in addition to the lack of scientific evidence to limit the use of ultrasound, above all in mild cases. Recently, Ripollés et al. published a prospective study with 240 patients in which it was found that ultrasound is an effective technique for distinguishing between complicated and uncomplicated AD, with a sensitivity of 84% and a specificity of 95.8% for the diagnosis of complicated AD.20

After the first prognostic classification of AD, described by Hinchey in 1978, multiple classifications have been proposed.6,21,22 Based on the classification used, the severity of the AD is catalogued differently, and few categorisations consider all the imaging findings that can be found in this pathology. Only the publication in 2016 by the World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES) does this,23 although it divides the findings between uncomplicated AD and complicated AD generically, without taking intermediate stages that may have significant differences with regard to the prognosis and hospital stay into account.8,21

This study intends to learn about the reality of AD management in Spain through the knowledge and daily practice of its radiologists.

From the results extracted from the analysis of the answers, it is noteworthy that only 48.4% of radiologists admit to having a well-defined protocol for radiological management of AD in their hospital. Nevertheless, the percentage of protocol use is greater in those [with] D-OS and with a greater number of beds. However, there are no statistically significant differences with regard to the protocol that is used (CT to start or ultrasound to start and CT for non-diagnosed, confusing or severe cases) based on the hospital organisation or size, as is reflected in Tables 3 and 4, but a greater tendency to use ultrasound in non-D-OS hospitals and in hospitals with fewer than 250 beds is noteworthy. It is likely that this is due to the structure and organisation of these departments, without being able to rule out greater access to ultrasound than CT. These results reflect the variability of the clinical practice and may owe in part to the personal experience of each radiologist.

When we analyse the daily practice of the radiologists surveyed, some divergences with respect to their own protocols are observed. During working hours, hospitals with more than 500 beds use the initial ultrasound systematically only in 18.3% of cases compared to 41.7% in those with fewer than 250 beds (p < 0.05). Similarly, both D-OS and non-OS use it in less than 30% of cases. These percentages show a lower rate of use of ultrasound than what they have established in their own protocols. This is likely because 30–50% of departments, regardless of their organisation or the hospital size, leave the choice of the technique to use to the radiologist, based on their experience or on the clinical severity of the AD. These results are also observed among in-person radiologists outside of working hours.

Despite the lesser use of ultrasound as an initial diagnostic technique for AD, approximately 72% of those surveyed are in agreement with using it as an initial technique for diagnosis and reserving CT for diagnostic concerns or inconclusive ultrasounds. This tendency is observed clearly in D-OS, even though it is in this type of organisation where this technique is used less in daily practice and where there is more disparity between the established protocols and real clinical practice. Paradoxically, in hospitals with fewer than 250 beds, the degree of radiologists' agreement with the use of ultrasound as an initial technique for the diagnosis of AD is 34%; however, it is in these hospitals where the real percentage of use of ultrasound is greater in daily practice (41.7%).

When the reasons why initial CT is used during working hours are analysed, the main reason alluded to is that said technique requires less experience to be reported. Other reasons are the lack of knowledge about the issue or the lack of organisation by OS. It is likewise surprising that in 33–42% of cases the reason is that the abdominal radiologists do not have sufficient knowledge in ultrasound of AD and that in up to 17% of D-OS hospitals, CT is used by requirement of the Surgery departments. On the contrary, it seems logical that the reason for the use of CT outside of working hours is the radiologist's lack of experience, since the night shifts may be undertaken by radiologists from other specialities, especially in larger centres. On the other hand, teleradiology would explain this tendency in smaller hospitals that do not have a 24-h in-person radiologist available.

In favour of ultrasound and, despite the abovementioned results, more than 91% of those surveyed are of the opinion that both general radiologists and abdominal radiologists should be trained in the diagnosis of AD by means of ultrasound. In that case, it would likely increase the use of said technique in real clinical practice and might also increase confidence among the rest of the specialists, surgeons in particular.

Hospitals with a greater number of beds and those with D-OS are mostly the ones that train radiodiagnostic residents. However, slightly more than half of radiologists belonging to these hospitals or departments are of the opinion that their residents leave well-trained in ultrasound for diagnosis of AD. This could be explained by the high rate of use of CT as an initial technique both during and outside of working hours, as well as by the fact of leaving the choice of using one technique or another to the radiologist based on their experience. Given the frequency of this pathology, we think that the resident training programmes should ensure proper training in diagnostic ultrasound for abdominal pain in the lower left quadrant.

With regard to ultrasound with contrast, approximately a fourth of the radiologists surveyed state that it may be useful both in diagnosis and in monitoring of AD, with no differences between hospital sizes or type of organisation. Despite this, only about 1% of the radiologists surveyed use it routinely and less than 7% acknowledge using it sometimes (hospitals with fewer than 500 beds, regardless of the organisation of the Radiology department). Approximately half of the radiologists do not believe that it can contribute additional information for making decisions. This is likely due to the sparse existing experience in the use of ultrasound with contrast for the diagnosis and monitoring of AD. On the other hand, the diagnosis of AD is usually done on an emergency basis, so the use of ultrasound with contrast would involve a longer examination time, only justified if it is demonstrated that it can provide additional information that changes the subsequent management of the patient (e.g., distinction between phlegmon and abscess). We have not found publications on this issue in the literature.

The use of classifications to stage the severity of the AD is variable; however, 95% of the radiologists are of the opinion that there should be a consensus to use the same categorisation. The classifications are used more frequently in D-OS radiology departments and in hospitals with a greater number of beds, with statistically significant differences with respect to the rest.

Today, the classification used most remains the Hinchey classification, despite this being a classification based on surgical findings that does not consider all the findings from imaging studies of AD. Taking into account that the management and prognosis of the AD depends on these findings, it would be reasonable to think that we should change classification to staging AD, applying one that considered everything in detail, regardless of the technique used for diagnosis (ultrasound or CT), and allows for establishing intermediate degrees of severity between uncomplicated diverticulitis and complicated diverticulitis. In fact, less than 50% of the radiologists surveyed think that the current classifications are sufficiently useful for staging the AD. In this same sense, there should also be greater agreement between radiologists and surgeons on the classification to be used.

Limitations of the studyThe project has several limitations. First, the survey was directed only at members of an abdominal radiology society, so it is difficulty to calculate the response rate with precision, given the uncertainty about the number of radiologists that really received the invitation. However, the absolute number of responses seems sufficiently representative of the reality of our departments. In addition, there is a balanced participation of different types of hospitals (hospital size and type of organisation), which suggests that the results may be generalised to real practice in the country. Second, the study may also be limited by a self-report bias, since it has been demonstrated that self-reports overvalue their own results.24 Lastly, the study period coincided with the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, during which it was recommended by scientific societies that CT be used instead of ultrasound wherever possible. This could have introduced a bias in favour of the use of CT. Nevertheless, the questions asked about the reasons for use of CT were multiple-choice questions, with the possibility of adding open comments. 37% of those surveyed included comments in this respect, and the influence of protocol changes due to the pandemic was not mentioned in any case.

In conclusion, there is a great variability with regard to the techniques used for the initial diagnosis of AD in our environment. Divergences among the protocols for radiological management of AD that are not negligible were observed from Radiology departments and real clinical practice. The greatest discrepancy is observed between what radiologists really think this usual health care practice should be (use of ultrasound as the initial technique) and what is really carried out. These results do not cease to be a reflection of the lack of consensus in the literature that depends, primarily, on the guidelines and geographic area consulted. Given that the clinical management and prognosis of AD depend on its classification, it does not seem logical that the Hinchey classification is still used in most settings. We believe it necessary to investigate new diagnostic classifications that take the radiological findings of AD into account. Their development and dissemination through scientific societies should facilitate proper and early decision-making on treatments in AD.

FundingThis project received no specific grants from public-sector agencies, commercial-sector agencies or non-profit organisations.

Authorship- 1.

Responsible for study integrity: NR.

- 2.

Study conception: NR, JMB, AT

- 3.

Study design: NR, JMB, AT

- 4.

Data acquisition: NR

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: NR, JMB, AA

- 6.

Statistical processing: NR, JMB

- 7.

Literature search: NR

- 8.

Drafting of the article: NR, JMB, AA

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: SP, MLC, AT

- 10.

Approval of the final version: NR, AA, AT, SP, MLC, JMB

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Presented as an oral communication at the XX Congress of the Sociedad Española de Diagnóstico por Imagen del Abdomen [SEDIA, Spanish Society of Diagnostic Imaging of the Abdomen]. Madrid, 21–22 October 2020.