Duret haemorrhages are haemorrhages occurring in the midline of the brainstem and mainly affect the midbrain and pons due to lateral-lateral compression of the brainstem resulting from uncal herniation. The fact that this is rarely seen means the radiology department plays a key role in its early diagnosis, helping clinicians and surgeons to assess its extension and other associated alterations. Nevertheless, it is acknowledged as having a high mortality rate, regardless of the cause and the treatment received.

We present the case of a 77-year-old woman with a history of diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure and chronic kidney failure secondary to hyperparathyroidism, who attended A&E after an accidental fall at home, with a direct blow to the right facial and parietal regions. Approximately one hour after the impact, she started vomiting, her blood oxygen levels dropped and she lost consciousness.

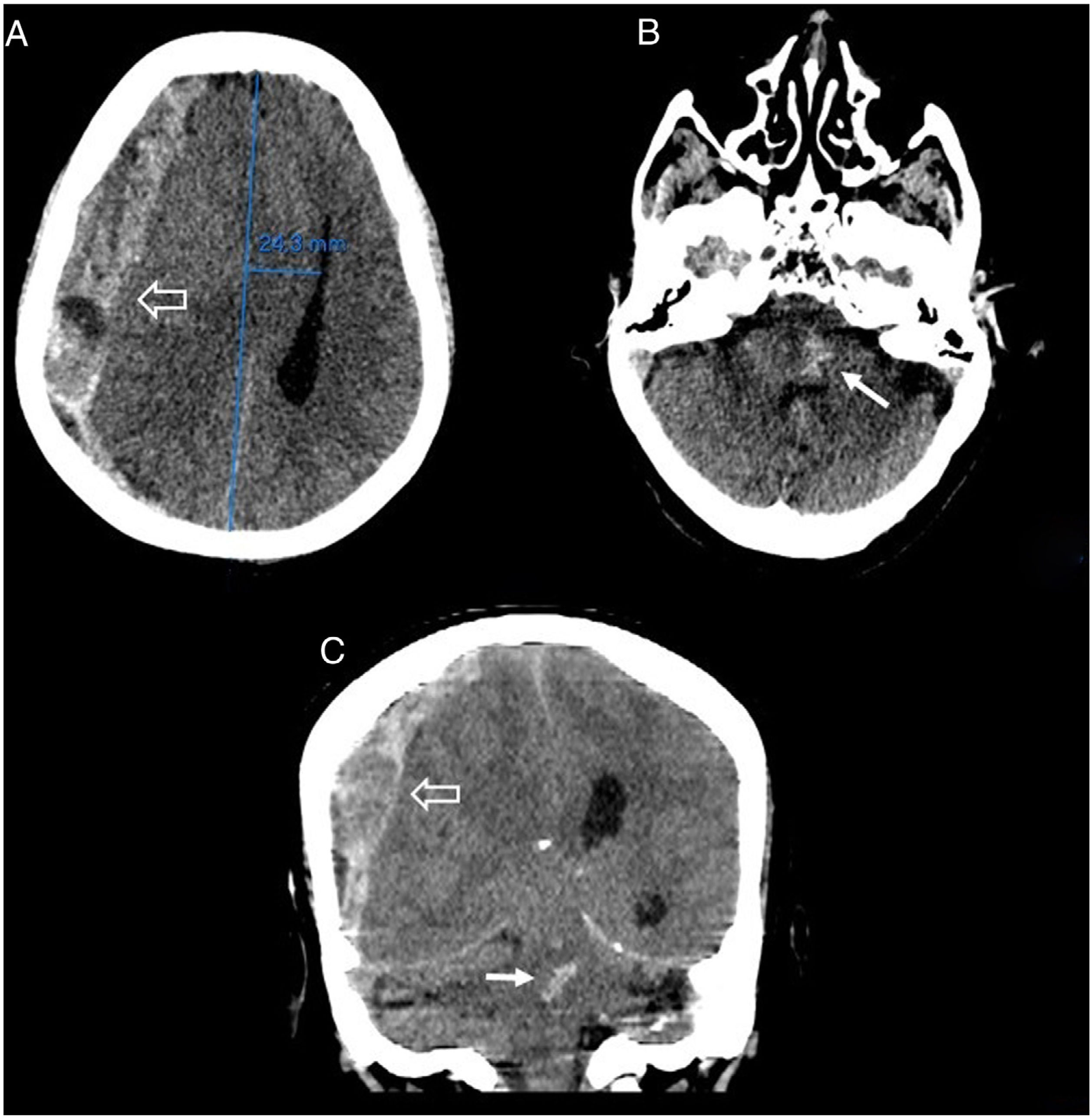

On clinical examination, the patient had a Glasgow Coma Scale of 4/15, blood pressure 223/97 mmHg, pH 7.3 and potassium 6.3 mmol/l. In view of her rapid clinical deterioration, a computed tomography (CT) brain scan without intravenous (IV) contrast was requested, showing a large acute subdural haematoma in the right hemisphere with severe signs of subfalcine and descending transtentorial herniation (Fig. 1A and C), associated haemorrhagic foci in the midbrain and pons (Duret haemorrhages), with extension to the cerebral aqueduct (of Sylvius) (Fig. 1B and C).

Brain CT images without intravenous contrast, axial (A and B) and coronal (C) slices. A right crescent-shaped extra-axial haemorrhagic collection of mixed density can be seen associated with an acute subdural haematoma in the right hemisphere, with a maximum thickness of 2 cm (hollow arrow). This collection is exerting marked expansive effects, causing subfalcine herniation with midline shift to the left of approximately 25 mm and almost complete collapse of the right ventricular system, as well as effacement of the basal cisterns in relation to descending transtentorial herniation, associated with hyperdense central foci in the pons and midbrain, suggestive of Duret haemorrhage (thin arrow), extending to the cerebral aqueduct (of Sylvius).

With these findings, Neurosurgery was contacted to assess drainage of the subdural haematoma, which was ruled out due to the patient’s poor prognosis and underlying diseases. She was admitted to Intensive Care, where she died a week later.

Traumatic brainstem haemorrhages can be grouped according to primary or secondary aetiologies. Primary aetiologies are commonly associated with the traumatic event, while secondary aetiologies are related to transtentorial herniation as a result of intractable intracranial hypertension, manifesting as Duret haemorrhages.1

Duret haemorrhages were described in 1874 by the French neurologist Henri Duret (1849–1921). They are not common and their aetiology is the subject of debate, although most authors agree that they are the result of brainstem involvement due to traumatic herniation of the uncus which, when displaced downwards, causes anterior-posterior stretching of the basilar artery and of the small vessels that penetrate through the posterior perforated substance, causing them to rupture.2 In addition, as veins are more compressible than arteries, herniation can lead to venous congestion and subsequent infarction in the draining veins of the anterior brainstem, followed by haemorrhagic transformation.1

In a study carried out from 2010 to 2021, the mean age of these patients was 69 years, with 87.5% having a previous diagnosis of high blood pressure and 75% on anticoagulant therapy, with a history of trauma in most cases.3 The general incidence in imaging studies is 5%–10% of all cerebral haemorrhages.1

In diagnosis, the initial non-contrast brain CT plays an essential role, as it shows the classic appearance of Duret haemorrhages: a small single haemorrhage located in the midline of the medulla oblongata or pons, near the pontomesencephalic junction. These haemorrhages can often be multiple or even extend to the cerebellar peduncles.4

Also appreciable will be descending transtentorial herniation, the second most common intracranial herniation, and in 75% of cases there is an associated acute subdural haematoma3 as a consequence of the high blood pressure and the herniation, seen in imaging tests as a crescent-shaped extra-axial hyperdense collection, which may also cause subfalcine herniation.5

As Duret haemorrhages have always been considered a fatal and irreversible event, and because surgical decompression can lead to more bleeding due to reperfusion, continuation of treatment is sometimes discouraged.1 However, early withdrawal of care prevents a true assessment of the outcomes of such lesions, as there have been rare cases in the literature in which good functional outcomes have been documented.

FundingThis study has not received any type of funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.