Supplement "Advances in Musculoskeletal Radiology"

More infoOur aim was to add to the small but growing body of evidence on the effectiveness of ultrasound-guided Achilles intratendinous hyperosmolar dextrose prolotherapy and introduce a novel, preceding step of paratenon hydrodissection with lidocaine in patients with chronic Achilles tendinosis resistant to rehabilitation therapy.

MethodsWe conducted a longitudinal, observational study on 27 consecutive patients diagnosed with Achilles tendinosis, in whom conservative treatment, ie, physiotherapy or shock wave therapy, had failed. A 2% lidocaine paratenon anesthesia and hydrodissection was followed by ultrasound-guided, intratendinous injections of 25% glucose every 5 weeks. Visual analogue scales (VAS) were used for pain assessment at rest, for activities of daily living, and after moderate exercise at the begining and at the end of the treatment. Moreover, tendon thickness and vascularisation were recorded at baseline and final treatment consultation. Effectiveness was estimated from scoring and relative pain reduction using a 95% CI. The non-parametric Wilcoxon test and a general linear model for repeated measures were applied. Statistical significance was established as p < 0.05.

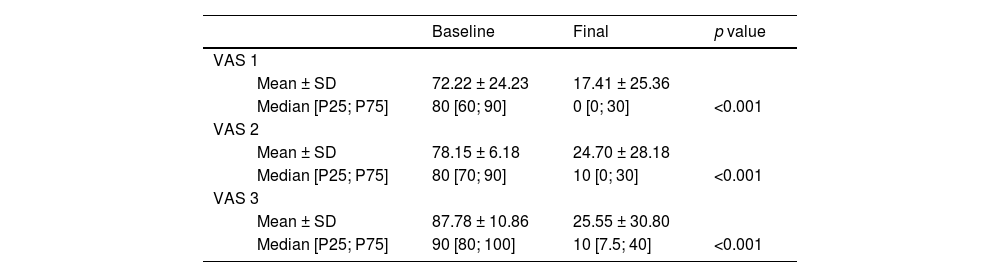

ResultsA median of 5 (1–11) injection consultations per patient were required. Pain scores decreased significantly in all three conditions (p < 0.001). Relative reductions were 75% in pain at rest (95% CI;61–93%), 69% in pain with daily living activities (95% CI; 55–83%), and 70% in pain after moderate exercise (95% CI; 57–84%). Tendon neo-vascularisation was significantly reduced (p < 0.001). We did not observe significant changes in tendon thickness (p = 0.083).

ConclusionsAchilles tendinosis treatment with paratenon lidocaine hydrodissection and subsequent prolotherapy with hyperosmolar glucose solution is safe, effective, inexpensive, and virtually painless with results maintained over time.

Nuestro objetivo era contribuir al pequeño pero creciente conjunto de datos sobre la eficacia de la proloterapia con glucosa hiperosmolar intratendinosa en el tendón de Aquiles guiada por ecografía e introducir un paso previo nuevo de hidrodisección del paratendón con lidocaína en pacientes con tendinosis aquílea crónica resistente a la fisioterapia.

MétodosLlevamos a cabo un estudio observacional longitudinal en 27 pacientes consecutivos con diagnóstico de tendinosis aquílea en los que el tratamiento conservador, es decir, fisioterapia o terapia con ondas de choque, había sido ineficaz. A la anestesia e hidrodisección del paratendón con lidocaína al 2% le siguieron inyecciones intratendinosas guiadas por ecografía de glucosa al 25% cada 5 semanas. Se utilizó la escala visual analógica (EVA) para evaluar el dolor en reposo, en las actividades de la vida diaria y después de ejercicio moderado, al inicio y al final del tratamiento. Además, el grosor y la vascularización del tendón se registraron en la consulta de inicio y final del tratamiento. La eficacia se estimó a partir de la puntuación y de la reducción del dolor relativo utilizando un intervalo de confianza (IC) del 95%. Se aplicaron la prueba de Wilcoxon no paramétrica y un modelo lineal general para medidas repetidas. La significación estadística se estableció en p < 0,05.

ResultadosSe necesitó una media de 5 (1-11) consultas para administrar inyecciones. Las puntuaciones del dolor disminuyeron significativamente en los 3 casos (p < 0,001). Las reducciones relativas fueron de un 75% para el dolor en reposo (IC del 95 %, 61-93%), un 69% para el dolor con las actividades de la vida diaria (IC del 95 %) y un 70 % para el dolor después de ejercicio moderado (IC del 95%; 57-84%). La neovascularización del tendón se redujo significativamente (p < 0,001). No observamos cambios significativos en el grosor del tendón (p = 0,083).

ConclusionesEl tratamiento de la tendinosis aquílea con hidrodisección con lidocaína del paratendón y proloterapia posterior con solución glucosada hiperosmolar es seguro, eficaz, barato y prácticamente indoloro, manteniéndose los resultados a lo largo del tiempo.

Achilles tendinosis affects the sedentary as well as the exercising population. Sports in which running is a key element provide a major focus for this kind of problem1. In the sedentary population, the lifetime cumulative incidence of tendinosis is 5.9%, whereas it rises up to 50% in elite athletes2. It is estimated that up to 29% of the Achilles tendinopathies will require surgical treatment, and thereof up to 31% of the patients will no longer do sports3,4. Pain in tendinopathy has been a matter of debate. The latest studies point to neo-vascularisation and neo-innervation as the ultimate triggers5–8. There is a large correlation between areas with intratendinous hyperaemia, as identified by Doppler ultrasound, and the zones of maximum pain reported by the patients8. Achilles tendinosis can be classified according to the affected anatomical region, ie, mid-portion tendinosis (2–6 cm from the bone insertion) and insertional tendinosis. The first is more prevalent and accounts for 66% of all injuries9. Patients with Achilles tendinosis frequently report having gone through several relapses throughout life, with increasing and increasingly difficult to control pain. Precisely this mechanism of damage, healing, and new damage by returning to daily physical activity favours injury and thus contributes to extracellular matrix degradation and changes in the collagen composition of the tendon fibre, which result in a biomechanically compromised tissue.

Although, at present, eccentric exercise is the first-line physiotherapeutic treatment for Achilles tendinosis10, this option is not enough in a non-negligible number of cases. Recently, a variety of percutaneous and extracorporeal treatments have emerged, such as shock wave therapy, infiltration treatment with platelet growth factors or stem cells, and Achilles intratendinous prolotherapy with hyperosmolar dextrose solution. The latter has been validated11,12 but still requires, according to the authors themselves, a larger body of evidence to confirm the promising, seemingly long-lasting results. The aim of this study was to evaluate Achilles tendinosis treatment with 25% dextrose intratendinous prolotherapy, preceded by ultrasound-guided paratenon hydrodissection with 2% lidocaine in patients with chronic Achilles tendinosis, resistant to rehabilitative measures, in order to add evidence to the long-term effectiveness of the technique and introduce a supportive and pain-relieving therapeutic step.

MethodsThis was a longitudinal, observational study (case series) on 27 consecutive patients diagnosed with Achilles tendinosis at the University Hospital Nuestra Señora de Candelaria (HUNSC), Tenerife, in whom conservative treatment had failed. The study was approved by the local Medical Ethics Committee for Research on Medicines (ABB- LID 2019-01) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

ParticipantsThe 27 enrolled patients (15 men and 12 women), aged 25–70 years, had suffered from Achilles tendinosis for more than three months (mean duration 28 months, range 3–120 months) with unsatisfactory treatment outcomes from one or more of the following rehabilitation techniques: eccentric exercise (n = 17), shock wave therapy (n = 9), and intra- tissue percutaneous electrolysis (n = 2). Exclusion criteria were insertional calcific tendinosis (irreversible tendinosis) and large intra-substance or tendon insertion ruptures. Patients underwent anaesthesia and hydrodissection of the paratenon with 2% lidocaine and subsequent ultrasound-guided injections with a 25%, i.e., hyperosmolar, glucose solution into the tendinous foci every 5 weeks.

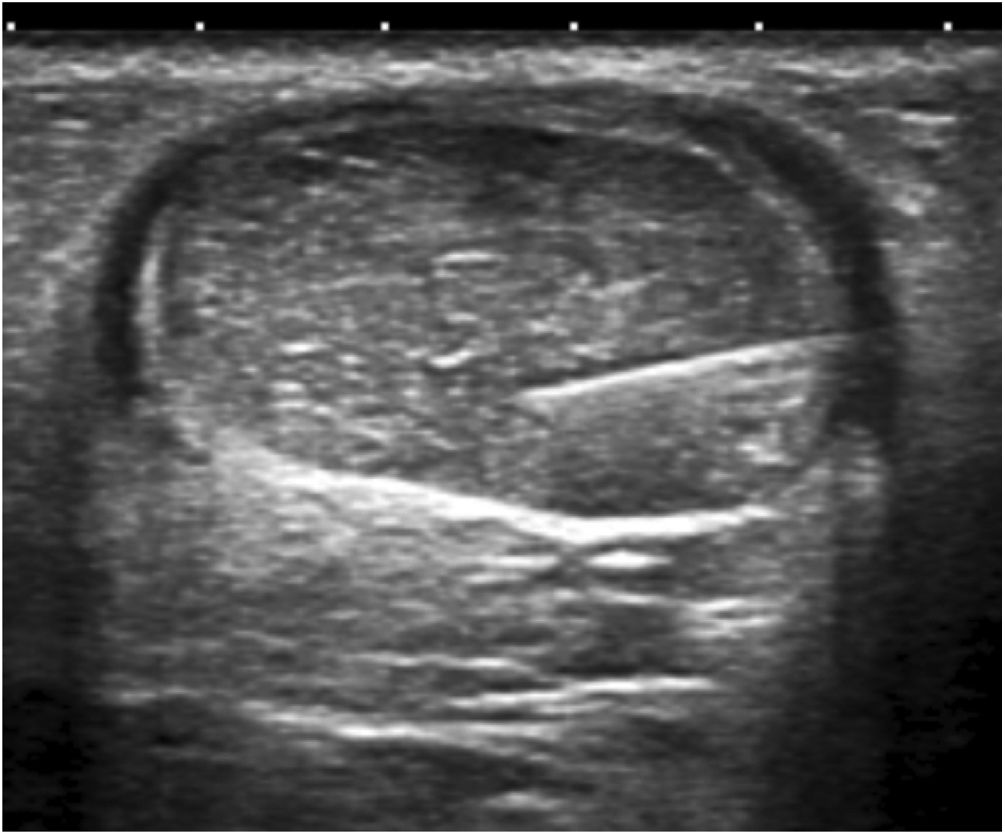

Ultrasonography: technique and applicationUltrasound studyThe diagnostic ultrasound studies as well as the percutaneous interventional procedure were performed by three experienced radiologists with a professional background of 9–20 years in musculoskeletal radiology. The technique was performed on patients in prone position with their feet hanging at the end of a table equipped with a hydraulic lift for proper height adjustment. A high-end Toshiba Aplio XG equipment (Toshiba Medical Systems, Japan) and 7-14 MHz linear transducers, 27-G needles, 10-ml luer lock syringes, sterile gloves, a sterile sleeve for the ultrasound probe, as well as material to form a sterile field were used. First, an axial and longitudinal exploration of the tendon was performed, keeping the probe parallel to the fibres in the longitudinal axis and perpendicular to the transverse axis to avoid anisotropy artefacts. Then, neo-vascularisation, calcifications, tendinous foci, and maximum thickness of each tendon were determined at baseline and after each of the interventions.

Maximum tendon thickness (in mm) was determined in the maximum anteroposterior (AP) axis. Only 2 of the 27 treated Achilles tendons exhibited insertional tendinosis, the other 25 were cases of mid-portion tendinosis.

Hydrodissection of the paratenon with 2% lidocaineTendinous foci were localised as hypoechoic areas of poorly defined margins, with or without associated hyperaemia, thus confirming the pain-producing zones upon palpation. These areas were marked on the skin, and a small bleb of 2% lidocaine was created cutaneously, subcutaneously without ultrasound guidance. Then, aseptic measures were taken, i.e., providing a sterile probe sleeve and cable, and a sterile field around the Achilles area and on the examination table. Past disinfecting the skin with povidone iodine, hydrodissection of the paratenon with 2% lidocaine was initiated. With the same luer lock 10-ml syringe used for bleb setting and under strict ultrasound control, the paratenon was separated from the adjacent subcutaneous fat tissue in order to break adhesions, mechanically destroy neo-vessels and neo-nerves that could have formed in the process of tendon degeneration, and lastly provoke an anaesthetic block to avoid any pain during the whole procedure. For an effective hydrodissection, 10 ml of 2% lidocaine were required. Figs. 1–3.

Next, the hypoechoic foci of tendinosis or collagen degeneration were infiltrated with a 25% glucose solution, mixing 1 ml of 2% lidocaine (20 mg/ml) with 1 ml of 50% glucose solution (25 g/50 ml) in a 10-ml luer lock syringe. Any air in the syringe was purged to avoid artefacts in the visual field. Each treatment consisted of infiltrating all the identified hypoechoic foci by performing a puncture technique parallel to the transducer or a free-hand technique (Figs. 4, 5). The total amount of administered solution depended on the number of foci, the resistance or intratendinous pressure, and the distribution of the solution within the tendon and towards the peritendon. Every patient was treated from 1 to 3 tendinous foci from avarage at each procedure.

At the end of the procedure, the tendon was checked for liquid distribution and leakage of the irritant solution to the peritendon. When there was considerable leakage, a discrete quantity of betamethasone (0.5 ml) was injected into this area to avoid paratenonitis, a potential complication of the procedure.

Patients were given the guidelines to adhere to during the following post-procedure weeks. These comprised avoiding non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), especially during the first 72 h, and recommended paracetamol 1 g every 8 h as the only permitted analgesic if pain occurred, as the latter does not inhibit COX-2 unlike the other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Likewise, patients were asked not to perform intense axial load exercise at least 72 h following the procedure. Thereafter, they were allowed to return to their habitual physical activity, including their routine eccentric exercise supervised by a professional.

A brief follow up by telephone or WhatsApp, asking for the patient’s current level of pain, was performed 24 months after the final treatment. VAS Assessment was included on those interviews using WhatsAPP.

Pain assessmentVisual analogue scale (VAS) grading from 0 to 100 was applied for pain assessment at baseline and the final treatment consultation. Pain at rest (VAS1), with activities of daily living (VAS2), and during or immediately after moderate exercise (VAS3) was recorded at baseline and the final treatment13. Variations were evaluated (a) as final scores of the VAS1, VAS2, and VAS3 and (b) as percentages of individual variations with respect to the baseline scores.

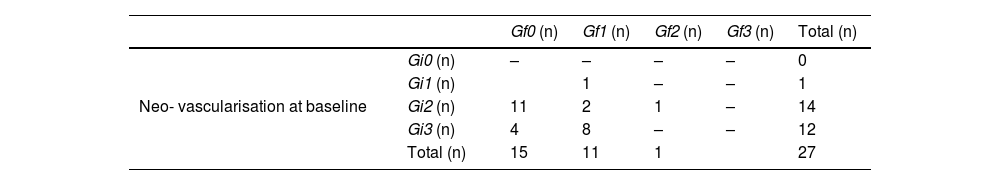

Vascularisation assessmentTo determine the progression of tendon neo-vascularisation, a classification system was applied: grade 0 (i.e., no neo-vascularisation), grade 1 (i.e., mild neo-vascularisation with 1-2 vessels entering the tendon), grade 2 (i.e., moderate neo-vascularisation with 3-4 vessels), and grade 3 (i.e., severe neo-vascularisation with more than 4 vessels). Thus, initial grades were termed Gi0, Gi1, Gi2, and Gi3 and the final grades Gf0, Gf1, Gf2, and Gf3.

Statistical analysesData for categorical variables were summarised as frequencies, and as mean ± SD and median (25th and 75th percentile, P25, P75) for numerical variables.

Treatment effectiveness was estimated applying a 95% CI, taking into account scoring and the relative decrease with respect to initial pain. Comparisons between baseline and final VAS scores and changes in tendon thickness and vascularisation were explored using the non-parametric Wilcoxon test for paired data and a general linear model (GLIM) for repeated measurements as appropriate.

Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All analyses were performed with the SPSS/PC software (V.24.0 for Windows; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and EPIDAT (V.3.0, Consellería de Sanidade Xunta de Galicia and Panamerican Health 0rganization).

Public and patient involvementNo members of the public or patients were involved in the design, conduct and interpretation of this study.

ResultsThis prospective case series included 27 consecutive patients with a mean age of 25 years, who suffered from Achilles tendinosis refractory to conventional treatment with eccentric exercise, shock wave therapy, or intra-tissue percutaneous electrolysis. Their dominant condition (91%) was a mid-portion tendinosis that contrasted with only 2 cases of insertional tendinosis. Repeating the percutaneous treatment every 5–6 weeks, a mean number of 5 treatment sessions (1–11) In other words, 25–30 weeks of treatment from average was required to achieve satisfactory results, i.e., VAS < 3.

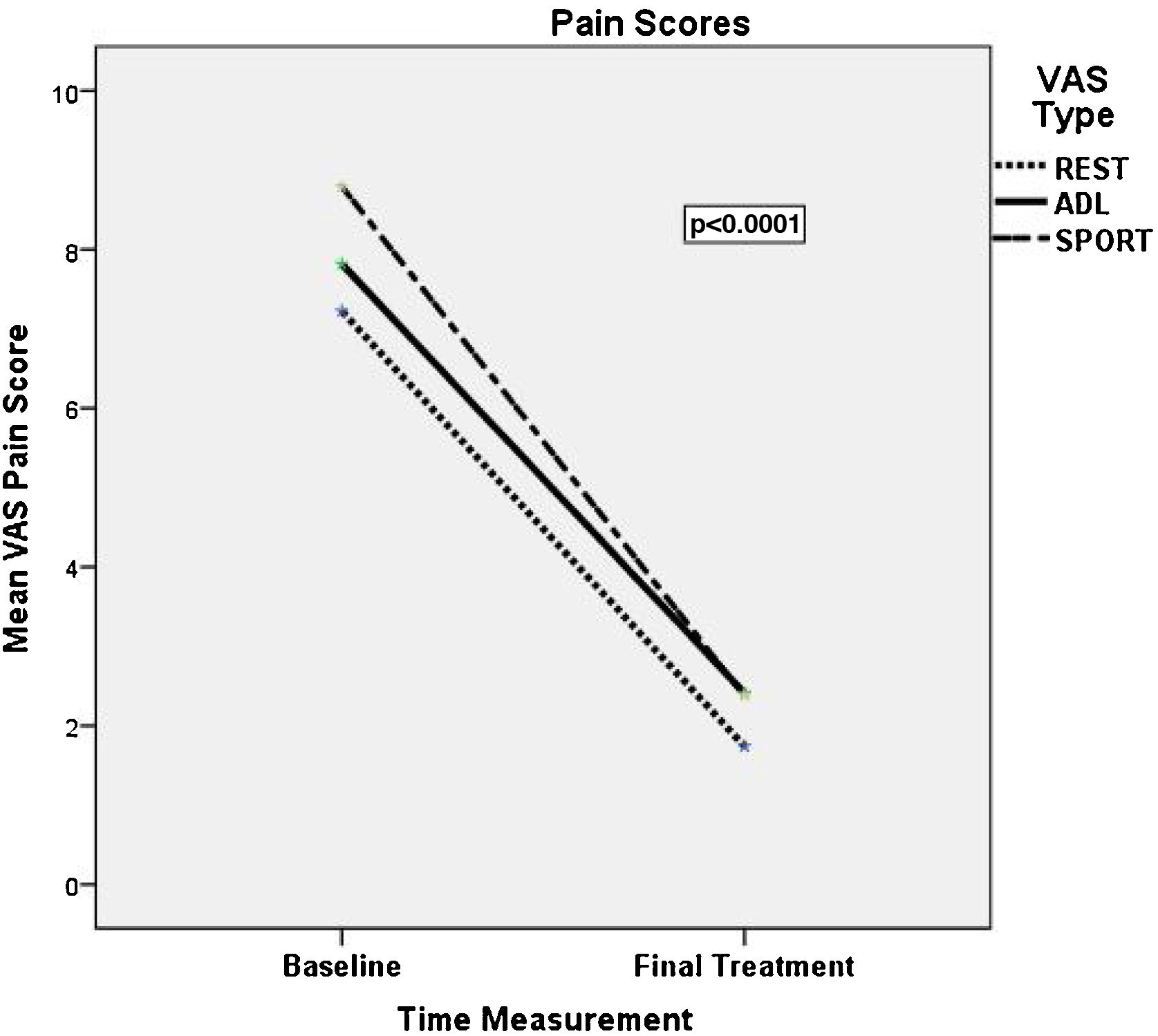

At inclusion, patients reported mean scores of 67, 76, and 86 in VAS1, VAS2, and VAS3 scale, respectively. After completing prolotherapy treatment, a statistically significant decrease (p < 0.0001) was observed in all three pain scores. The relative decrease compared to the initial resting score was 75% in VAS1 (95% CI; 61–93%), 69% in VAS2 (95% CI; 55-83%), and 70% in VAS3 (95% CI; 57–84%). Only two patients reported no change with respect to their initial pain scores. The statistics that describe the decrease in pain (mean, median, and p values) in all three conditions are given in Table 1 and Fig. 6.

Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) at the baseline and at the final treatment consultation.

| Baseline | Final | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS 1 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 72.22 ± 24.23 | 17.41 ± 25.36 | ||

| Median [P25; P75] | 80 [60; 90] | 0 [0; 30] | <0.001 | |

| VAS 2 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 78.15 ± 6.18 | 24.70 ± 28.18 | ||

| Median [P25; P75] | 80 [70; 90] | 10 [0; 30] | <0.001 | |

| VAS 3 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 87.78 ± 10.86 | 25.55 ± 30.80 | ||

| Median [P25; P75] | 90 [80; 100] | 10 [7.5; 40] | <0.001 | |

VAS1 = pain at rest, VAS2 = pain with activities of daily living, VAS3 = pain during or immediately after moderate exercises SD (standar desviation); p value* Wilcoxon NPar Test.

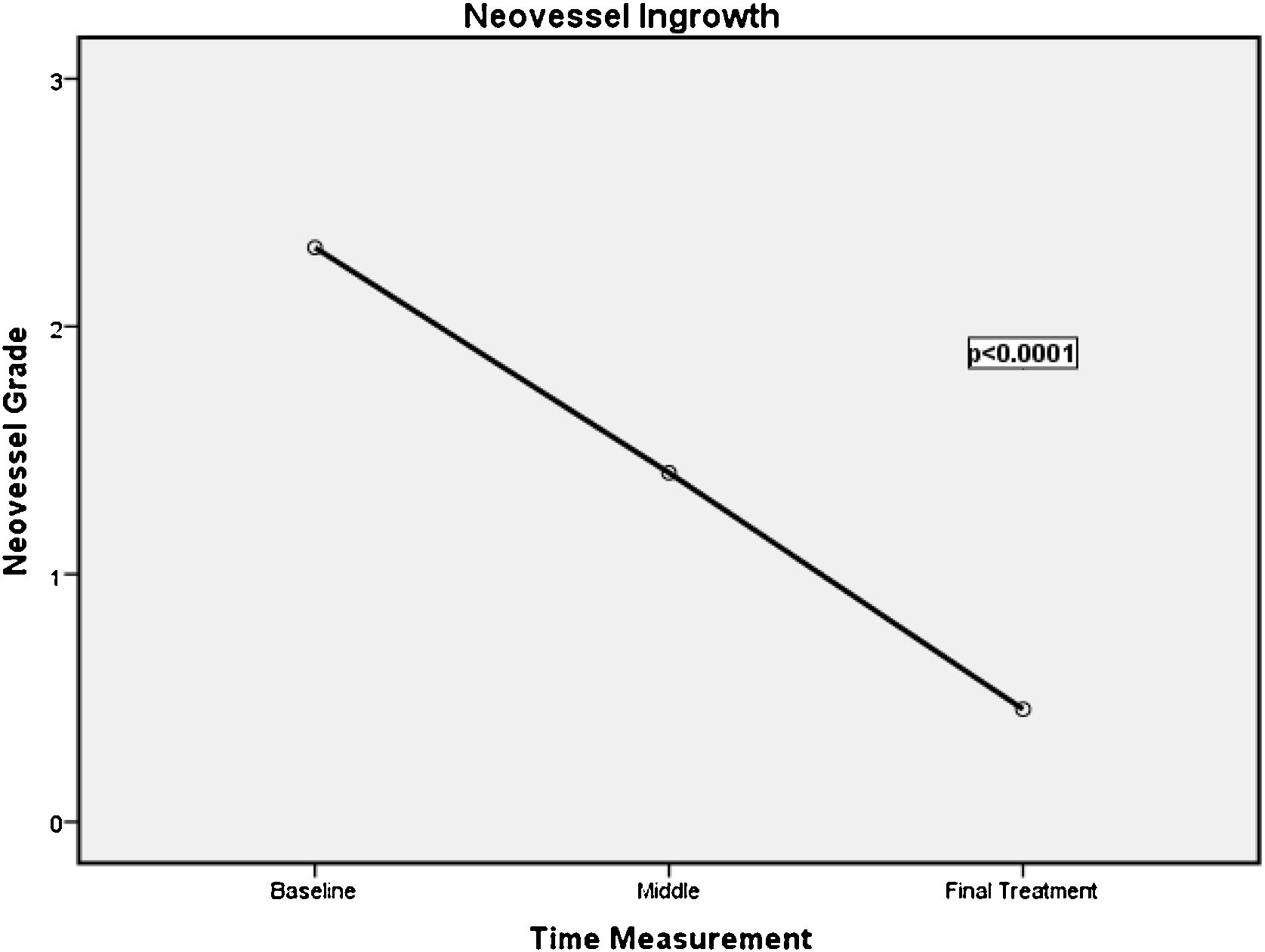

In the course of therapy, visible vessels in the hypoechoic foci diminished throughout the tendon layer; tendon neo-vascularisation reflected a statistically significant (p < 0.001) decrease (Fig. 7). Individual improvement was observed in each patient. Initial vascularisation was classified as Gi1 in 1, Gi2 in14, and Gi3 in 13 patients. Of note, 78.6% of the treated tendons changed from a vascularisation degree Gi2 to Gf0, and 100% with Gi3 passed to Gf1. Only the patient who started with Gi2 maintained the grade (Gf2). Thus, by the end of the treatment, 96% of the tendons were classified as either grade 0 or grade 1 on the vascularisation scale (Table 2, Fig. 7).

Vascularity grading at baseline and final treatment consultation Neo- vascularisation by the end of treatment.

| Gf0 (n) | Gf1 (n) | Gf2 (n) | Gf3 (n) | Total (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neo- vascularisation at baseline | Gi0 (n) | – | – | – | – | 0 |

| Gi1 (n) | 1 | – | – | 1 | ||

| Gi2 (n) | 11 | 2 | 1 | – | 14 | |

| Gi3 (n) | 4 | 8 | – | – | 12 | |

| Total (n) | 15 | 11 | 1 | 27 |

Neo-vascularisation grades at baseline: Gi0, grade 0; Gi1, grade 1; Gi2, grade 2; Gi3, grade 3; Neo- vascularisation grades by the end of treatment: Gf0, grade 0; Gf1, grade 1; Gf2, grade 2; Gf3, grade 3; n, absolute frequency; p value* Wilcoxon NPar Test.

p value <0.001*.

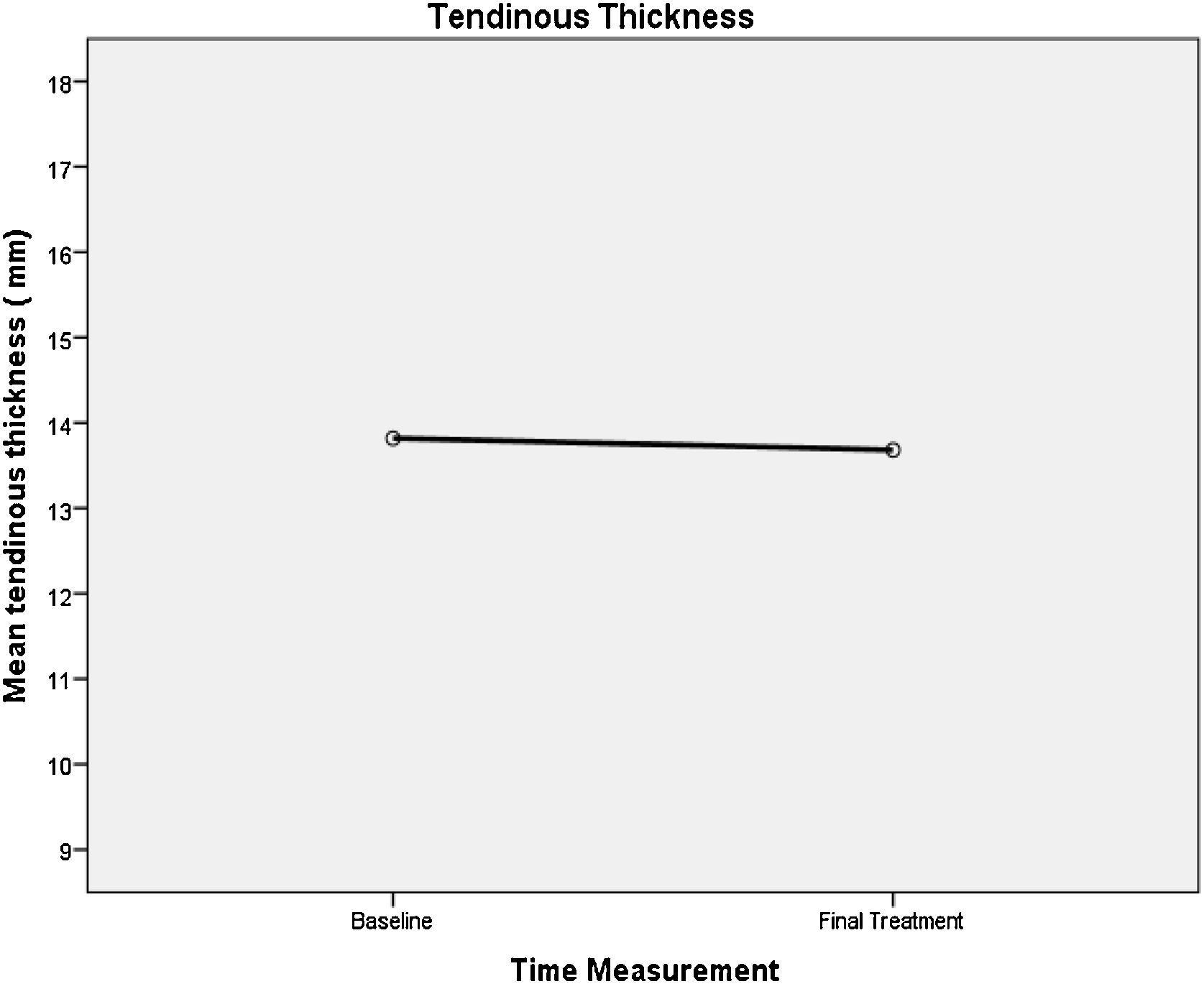

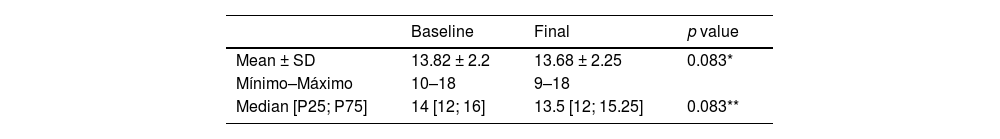

We did not observe significant changes in tendon thickness, neither between initial and final means (13.82 mm, 13.68 mm; p = 0.083) nor in medians (percentiles P25, P75; p = 0.083) of the initial (12, 14, 16) and the final maximum AP (13.5, 12, 15.25) (Table 3 and Fig. 8).

Sonographic Evaluation of the Achilles Tendon Thickness. Maximum anteroposterior diameter (mm) at baseline and at final session.

| Baseline | Final | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | 13.82 ± 2.2 | 13.68 ± 2.25 | 0.083* |

| Mínimo–Máximo | 10–18 | 9–18 | |

| Median [P25; P75] | 14 [12; 16] | 13.5 [12; 15.25] | 0.083** |

p value * T-Test Pair **Wilcoxon Singed rank NparTest.

No adverse effects or complication were observed during or after the procedure.

DiscussionThis study aimed to add evidence to the little data available on tendinosis and its possible treatment. Our work supports data, obtained by Maxwell et al and Ryan et al.11,12, which represent the largest series on treatment and follow up of Achilles tendinosis published to date and provide an excellent reference with which tocompare our results.

Reducing the severe pain patients with Achilles tendinosis suffer, not only in moderate exercise but also in their daily activity and even at rest, is the goal of conventional therapies, which as of yet have been applied with doubtful success. Today, eccentric (heel-drop) exercise is the gold standard physiotherapy for Achilles tendinosis, included in various guides and internationally validated (10). When this option is not enough and fails to mitigate the patient's pain, different recently published, percutaneous and extracorporeal treatments come into play, such as shock wave therapy, dry needle puncture, high volume injections, treatment with platelet growth factors, and prolotherapy with hyperosmolar glucose11–16. Our ultrasound-guided, percutaneous treatment method encompassed paratenon hydrodissection with 2% lidocaine and intratendinous prolotherapy with 25% dextrose and led, under these conditions, to promising results. In addition, it combined two of the described percutaneous treatment methods in one procedure, i.e., paratenon high volume hydrodissection and prolotherapy with a hyperosmolar glucose solution. Notably, our study describes for the first time paratenon hydrodissection with 2% lidocaine, fulfilling a dual purpose. On the one hand, the tendon is anaesthetised such that the patient does not experience any pain during the procedure. Importantly, pain is one of the principle handicaps attributed to prolotherapy and tendon treatments in general. On the other hand, neo-vessels that penetrate the paratenon are more likely destroyed using the highest possible volume.

Pain is known to be a subjective symptom. By using the same visual analogue scale for pain evaluation as other authors, we were able to compare results13. All three baseline mean values, VAS1, VAS2, and VAS3, were somewhat higher in our patients than in the two previously published series11,12. After completing prolotherapy, pain had decreased significantly and to similar final scores in all three conditions, also reflected by the relative decrease. Moreover, the maximum relative reduction in pain at rest resembled the data found by Maxwell et al in his series of 36 cases11.

The mean change in tendon thickness of 0.1 mm by the end of treatment was not significant, similar to the mean decrease of 0.6 mm found by Maxwell et al.11 and of mm in the 108 treated tendons reported by Ryan et al.12.

Current studies on tendinopathies and their appropriate treatment have focused on the concurrent neo-vascularisation as a probable source of pain17. Tendons by definition are virtually avascular and therefore prone to hypoxaemia, which may lead to inadequate repair in conditions of acute or chronic stress. Micro-dialysis studies have demonstrated that lactate in tendinosis persists at rest, suggesting hypoxia in tendinopathy even beyond physical stress18. In a recent work, Järvinen TAH explained the paradox of hypoxaemia despite extensive neo-vascularisation in tendinosis based on the theory of hyper-permeability19. Basically, this author discusses that hypoxia-stimulated tendon neo-vascularisation and its consequent secretion of vascular growth factors would lead to hyper-permeable vessels, probably due to an altered lumenisation, i.e., the structural integrity of endothelial cells and pericytes in the vessel wall. This in turn, would lead to poor tissue perfusion and clearing of fibrin-rich exudates from the extra-luminal tissue, thus leading to fibrinoid degeneration of the tendon19. Latest advances in genetics and vascular biology have identified genes responsible for adequate vascular stabilisation and lumenisation, among them R-Ras20. A lack of R-Ras expression is responsible for hyper-permeable neo-vessels in distinct diseases like, e.g., retinopathy, cancer, and evidently musculoskeletal ischaemia. On the contrary, restoration of R-Ras gene activity in mouse endothelial cells reverts the hypoxaemia phenomena20, which opens up a completely new and unexplored field in the treatmentof this pathology.

In our case series as well as in those published by Maxwell et al and Ryan et al.11,12, initial vascularisation grade 2 was predominant (59%), followed by grade 3 in 35% of the tendons. We would like to emphasise that by the end of treatment 100% of the tendons were grade 0 or grade 1, a significant decrease, individually presented in Table 3. The mean decrease in tendon vascularisation in the aforementioned studies was significant as well, although individual changes were not given; however, most likely none of the tendons will have worsened.

Limitations and strengthsA certain limitation of our study is the lack of a control group or groups with other therapies—as presented in the above mentioned works11,12—that would allow comparison. There are no clinical trials that assess the use of 25% glucose vs placebo or that blind patients for pain evaluation before and after treatment, taking into account the subjectivity of pain perception. In this regard, our study provides objective, ultrasound-based evidence of a significant decrease in defective neo-vessels, which would perpetuate inflammation and structurally affect tissues and which seem to correlate with pain17. All our patients had undergone other therapies without success and exhibited a high degree of pain and a high level of neo-vascularisation. As Maxwell et al mentioned in their conclusions11: “… further clinical studies comparing hyperosmolar dextrose injections with other therapies and with no therapy are required”.

Achilles tendinosis is a health problem that affects both athletes and sedentary persons. Its actual incidence is unknown. Standing for a long time supporting the body weight as well as sports based on running are recognised risk factors for this condition. Achilles tendinosis is a challenge for health care professionals, as there is still very little information available on its etiopathogenesis and adequate treatment.

Achilles intratendinous prolotherapy with a hyperosmolar dextrose solution is a cheap, safe, and long-lasting therapeutic method, validated with the longest case series (108 Achilles tendons) in this field as of yet12. The pain resulting from injecting the hypertonic, irritant solution into the Achilles tendon during prolotherapy is perhaps the most limiting factor for its regular use. Taking into account the latter and the high volume treatments with physiological saline described by Chang et al.14, we decided to incorporate a novel, foregoing step of anaesthesia and hydrodissection of the paratenon with 2% lidocaine into the originally described technique11,12. This allowed us to perform painless Achilles infiltration with hypertonic solution and, in addition, to break potential adhesions, neo-vascularisation and neo-innervation that irrigate and innervate the hypoechoic, tendinous foci, thus contributing to the outcome of the prolotherapy itself.

The histopathological changes that accompany prolotherapy had been suggested by Banks AR in 199121. The author had proposed four basic mechanisms to bring about repair and recovery of the damaged tissue: (1) The injected solution would cause osmolarity-induced cell dehydration and in consequence a local inflammatory reaction. (2) Cell debris would attract granulocytes, which in turn would secrete humoral factors and thus lead to macrophage infiltration. (3) The macrophages would phagocytise the cell debris and secrete growth factors that attract and activate fibroblasts. (4) Finally, the fibroblasts would produce collagen, resulting in a re-organised, stronger tendon connective tissue than before infiltration. However we are aware of discordant findings in animal studies regarding density, viability and recruitment of proteoblasts or tendon vascularisation after administration of prolotherapy so more Studies about histopathological mechanisms are needed.

In our study, we were able to confirm the increase in tendon resistance with each administration of hyperosmolar solution, which seems to confirm the latter point proposed by Banks. Functional MRI using T2 relaxation maps before, during, and after prolotherapy treatment could help confirm this hypothesis—a stimulus for future research.

Likewise, we have observed a continuous decrease throughout the tendon layer in numbers of visible vessels in the hypoechoic foci. This progressive decrease was reflected in reduced pain determined by VAS grading (Fig. 6). Our observation favours the hypothesis that the usually reported pain may be largely due to the neo-innervation that accompanies neo-vascularisation17.

Ultrasound-guided dry puncture, also known as percutaneous tenotomy, is a technique that has been performed with satisfactory results in recent years15,16, a fact that brings about a debate on the need of adding irritant or hypertonic solutions to percutaneous treatment. Further studies are required to compare both methods to clarify the question. We also believe that other percutaneous treatments like shock wave therapy and platelet-rich plasma infiltration should be included in such a study.

Alternatively, stabilising the damaged, malformed neo-vessels during stress-induced hypoxaemia and thus reverting hypoxia-derived phenomena could be the definitive treatment approach in this pathology. Progress in vascular biology and related therapies in the near future may finally solve these questions.

ConclusionPercutaneous Achilles tendinosis treatment combining anaesthesia and paratenon hydrodissection with subsequent prolotherapy with hyperosmolar glucose solution is a safe, cheap, and virtually painless technique. It results in a progressive reduction in neo- vessels throughout the tendon layer as well as a significant decrease in the perception of pain at rest, with daily physical activity, and during moderate exercise, which is maintained over time.

A decrease in tendinosis neo-vascularisation can be attained with percutaneous prolotherapy.

Paratenon lidocaine hydrodissection ensures an asymptomatic percutaneous procedure and releases any potential tissue adherence.

The achieved decrease in neo-vascularisation was proportional to the decrease in pain intensity assessed with visual analogue scales.

The effects of prolotherapy lasted over time within a 24-months follow up.

Ultrasound-guided, percutaneous tendinosis treatment with lidocaine paratenon hydrodissection followed by glucose infiltration into hypoechoic foci is an inexpensive and available method with seemingly excellent long-term results.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

Authorship- 1

Responsible for study integrity: ABB

- 2

Study conception: ABB

- 3

Study design: ABB

- 4

Data acquisition: ABB, MLNM, PMG y ACL

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: LIPM

- 6

Statistical processing: LIPM

- 7

Literature search: ABB

- 8

Drafting of the manuscript: ABB

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Without the invaluable help and patience of Juana María González Acosta, graduate in nursing (DUE) at the Radiology Department of the HUNSC, Tenerife, this study would not have been possible.