To describe the normal patterns of cerebellar activation in specific cerebral functions (motor, language, memory) and their topographical correlations in the cerebellar cortex on functional magnetic resonance imaging.

Materials and methodsWe evaluated 25 healthy subjects (8 women and 17 men; 23 right-handed and 2 left-handed; age range, 16–64 years), who did language, memory, and motor tasks while undergoing 1.5T functional magnetic resonance imaging.

ResultsWe assessed functional activity of the cerebellum associated with motor, language, and memory components, describing their relations with topographical regions of the cerebellum and their functional relations with areas in the cerebral cortex.

ConclusionsKnowledge of the normal patterns of morphological characteristics and functional behaviour in the cerebellum as well as their relations with the brain is important for radiologists and clinicians evaluating the cerebellum and possible pathological conditions that affect it.

Describir los patrones normales de activación en el cerebelo de funciones específicas cerebrales (motor, lenguaje, memoria) y su relación topográfica en la corteza cerebelosa utilizando resonancia magnética funcional.

Materiales y métodosSe evaluaron 25 sujetos sanos, 8 mujeres y 17 hombres de entre 16 y 64 años, 23 diestros y 2 zurdos, mediante resonancia magnética funcional basada en tareas de lenguaje, memoria, motor y visual, en equipo de resonancia de 1.5 Teslas.

ResultadosSe caracterizó la actividad funcional en el cerebelo asociada a los componentes motores, de lenguaje y memoria, describiendo la relación con las regiones topográficas, así como su relación funcional con áreas corticales cerebrales.

ConclusionesEl conocimiento sobre los patrones de normalidad de las características morfológicas y del comportamiento funcional en el cerebelo, así como su relación con el cerebro, es importante para el radiólogo y médico clínico en la evaluación del cerebelo y sus posibles condiciones patológicas.

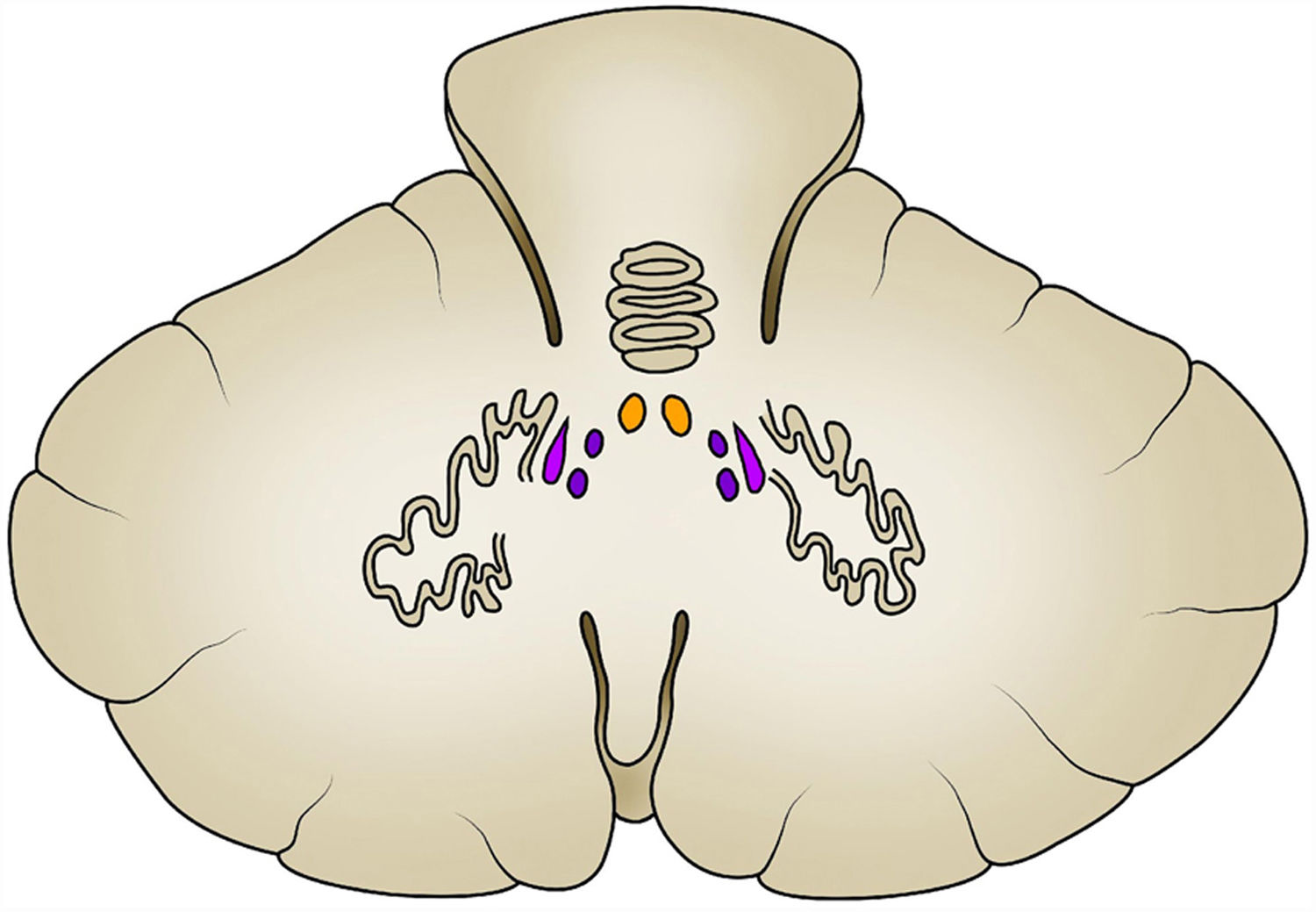

The internal configuration of the cerebellum makes it possible to identify a grey matter component called, on its surface, the cerebellar cortex and, in its interior, the deep nuclei. The cerebellar cortex is composed of three layers: the molecular layer, which is the most superficial; the middle or Purkinje cell layer, and the deep or granular layer; there are four deep nuclei known, from medial to lateral as the fastigial, emboliform, globose and dentate nuclei, respectively (Fig. 1).

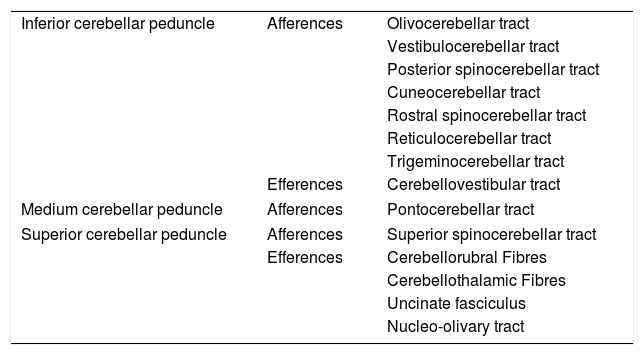

Deep in the cerebellar cortex there are also tracts of white matter that correspond to intrinsic, afferent and efferent fibres. These tracts run through the superior, middle and inferior cerebellar peduncles to structurally and functionally connect the cerebellum with the brain and spinal cord. The middle cerebellar peduncle is the largest, and the pontocerebellar fibres of the contralateral pontine nuclei and cerebral cortex pass through it; the superior cerebellar peduncle consists mainly of efferent fibres from the deep nuclei of the cerebellum, while multiple afferent tracts pass through the inferior cerebellar peduncle; its main reference comes from the deep core of the fastigial nucleus (Table 1).

Association pathways of the cerebellum.

| Inferior cerebellar peduncle | Afferences | Olivocerebellar tract |

| Vestibulocerebellar tract | ||

| Posterior spinocerebellar tract | ||

| Cuneocerebellar tract | ||

| Rostral spinocerebellar tract | ||

| Reticulocerebellar tract | ||

| Trigeminocerebellar tract | ||

| Efferences | Cerebellovestibular tract | |

| Medium cerebellar peduncle | Afferences | Pontocerebellar tract |

| Superior cerebellar peduncle | Afferences | Superior spinocerebellar tract |

| Efferences | Cerebellorubral Fibres | |

| Cerebellothalamic Fibres | ||

| Uncinate fasciculus | ||

| Nucleo-olivary tract | ||

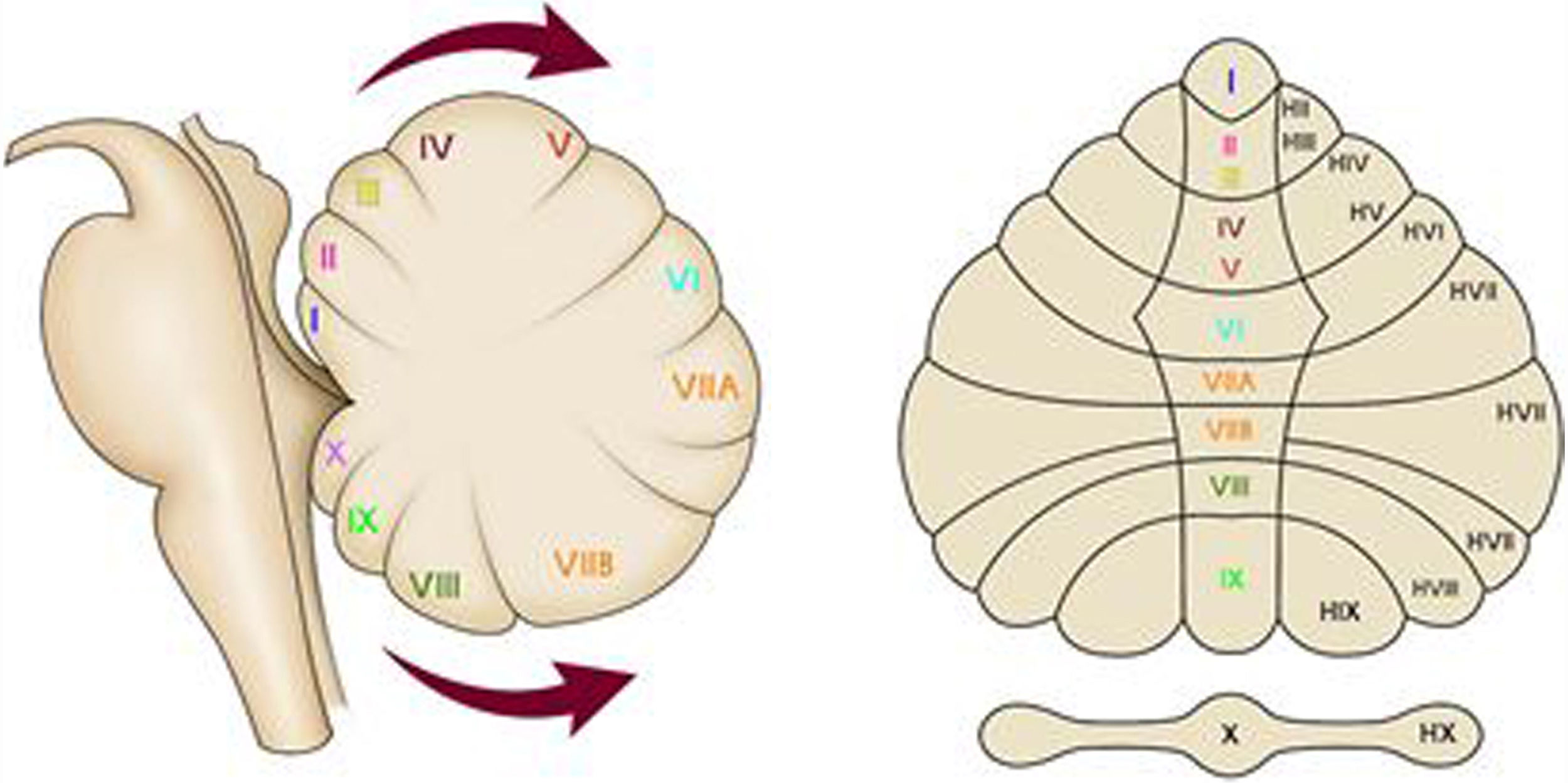

As for the external configuration of the cerebellum, it is divided into a medial structure called the vermis and two lateral structures called cerebellar hemispheres, which are organised in sheets with a transverse arrangement, situated one after the other in the face-caudal direction. These sheets are grouped into anterior, posterior and flocculonodular lobes, which have a phylogenetically different origin; the oldest is the archicerebellum, which is responsible for maintaining body balance both at rest and in motion and for the limbic control of emotions, autonomic manifestations, sexuality and memory; it is followed by the paleocerebellum, which regulates the tone of the proximal axial musculature for postural control and, finally, the neocerebellum, which coordinates the muscle groups for performing fine and precise movements, in addition to controlling planning, strategy, learning, memory and language Although there are different ways to classify the lobes of the cerebellum, for this study the nomenclature proposed by Larsell in 1951 was used, which divides the sheets into 10 segments, denominated with Roman numerals from I to X, both for the vermis and for the cerebellar hemispheres, attaching to the latter a letter “H” at the end of the Roman numeral (Fig. 2). It should be noted that the anterior cerebellar lobe comprises the vermian segments from I to V; the posterior lobe, segments VI through IX, and the flocculonodular lobe, segment X.

In recent decades, multiple investigations in humans have suggested representations of the body in the cerebellum, in the manner of somatotopic maps, as evidenced in studies of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) when applying different paradigms for the assessment of motor, cognitive, and language tasks.1–3 These studies have demonstrated the presence of two sensorimotor homunculi in the cerebellar cortex: the first, located in the anterior lobe, and the second, in lobe VIII.1 In this way, certain clinical signs and symptoms have been correlated with specific topographic areas: gait ataxia has been associated with the vermis of lobes II and III; motor incoordination in lower limbs, with lobes III and IV and in upper limbs, with lobes V and VI; and oculomotor alterations with lobes VIII and IX.4,5 More specific studies have detailed even the movements of the fingers and their sensory and motor activation in the cerebellum.6 Likewise, in previous studies we observed that when performing a motor task with an upper limb, there was activation in the cerebellum ipsilateral to the hemibody that performs the function, and contralateral to the area of activation in the cerebral cortex,7 findings similar to those described by other authors in language assessment studies, where ipsilateral cerebellar hemisphere activation has been observed in healthy right-handed adults in parallel with activations of the contralateral Broca's and Wernicke's areas.8 These findings suggest that there are specific cerebellocerebral connections for certain brain functions.

The objective of this study is to describe the activation pattern of specific functions in the cerebellum and its topographic relationship to the cerebellar cortex using fMRI.

Material and methodsSubjectsThe study included 25 healthy subjects, 17 men and 8 women between 16 and 64 years old, 23 right-handed, 2 left-handed. In the exclusion criteria, traumatic, vascular, neurological or psychiatric personal or family history that could alter brain function or study results were taken into account. The study was approved by the hospital's Ethics Committee, and written informed consent was obtained from all the patients.

Acquisition protocolThe studies were performed in a 1.5T resonance device (Avanto, SIEMENS; Erlangen, Germany). The subjects were placed in the supine position with immobilisation of the head inside the antenna. An enhanced sequence was acquired in T1, from the vertex to the posterior fossa of the brain (FOV=256mm, TE=3.37ms, TR=1900ms, angulation=15°, slice thickness=1mm, voxel size=1mm3). For the functional studies, 20 interleaved axial cuts parallel to the tentacle were acquired, from the vertex to the fourth ventricle, using gradient echo-based EPI sequences for each functional study (FOV=240, slice thickness=6mm, TE=45ms, TR=2000ms, angulation=90°, voxel size=3.75mm×3.75mm×6.00mm). The tasks were explained before the session and before the start of each functional sequence.

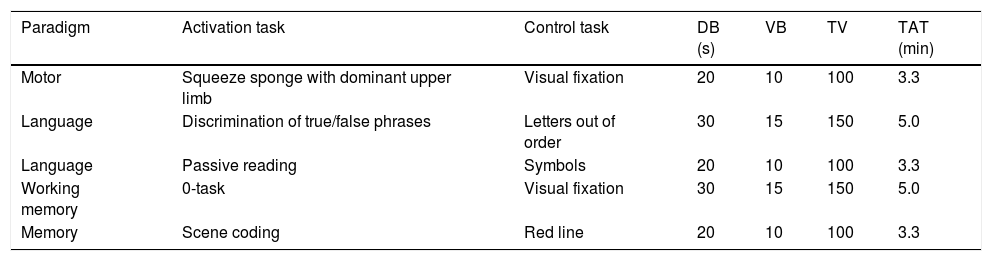

The subjects were presented with five paradigms that consisted of 10 blocks that alternated activation and control conditions, five blocks per condition, all of equal duration (Table 2). All stimuli were presented visually:

- •

Motor task. During the activation phase, an image of a hand is projected on the screen, where the subject is instructed to squeeze a sponge in the dominant hand. During the control phase, the subject must remain at rest and alert to the screen.

- •

Receptive language task. During the activation phase, a text is projected in Spanish and the subject is instructed to read it mentally. During the control phase, random symbols are projected and the subject is instructed to follow them with the eyes as though reading.

- •

Receptive/productive language task. During the activation phase, a phrase related to everyday life is projected (e.g., “A tool for cutting is a knife”) and the subject is asked to indicate with the index finger of the dominant hand when the phrase is true. In the control phase, letters are projected out of order, and the subject is asked to indicate in the same way when he/she sees the letter X.

- •

Working memory task. During the activation phase, a block of letters is projected to the subject, who is asked to memorise the first letter of each block and indicate with the index finger of the dominant hand when the letter reappears on the screen. In the control phase, a white screen is presented with a black cross in the middle and the subject is instructed to visually focus to be alert to the new block of letters.

- •

Scene coding task. In the activation phase, images of interior and exterior places are projected to the subject; the subject must indicate with the index finger of the dominant hand when the place is outside. In the control phase, images of similar colours are presented with a vertical red line, and the subject is asked to indicate with the index finger when the red line is on the right.

Detailed description of the tasks used in each paradigm.

| Paradigm | Activation task | Control task | DB (s) | VB | TV | TAT (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motor | Squeeze sponge with dominant upper limb | Visual fixation | 20 | 10 | 100 | 3.3 |

| Language | Discrimination of true/false phrases | Letters out of order | 30 | 15 | 150 | 5.0 |

| Language | Passive reading | Symbols | 20 | 10 | 100 | 3.3 |

| Working memory | 0-task | Visual fixation | 30 | 15 | 150 | 5.0 |

| Memory | Scene coding | Red line | 20 | 10 | 100 | 3.3 |

DB: duration of each block; TAT: total acquisition time; TV: total volumes; VB: volumes per block.

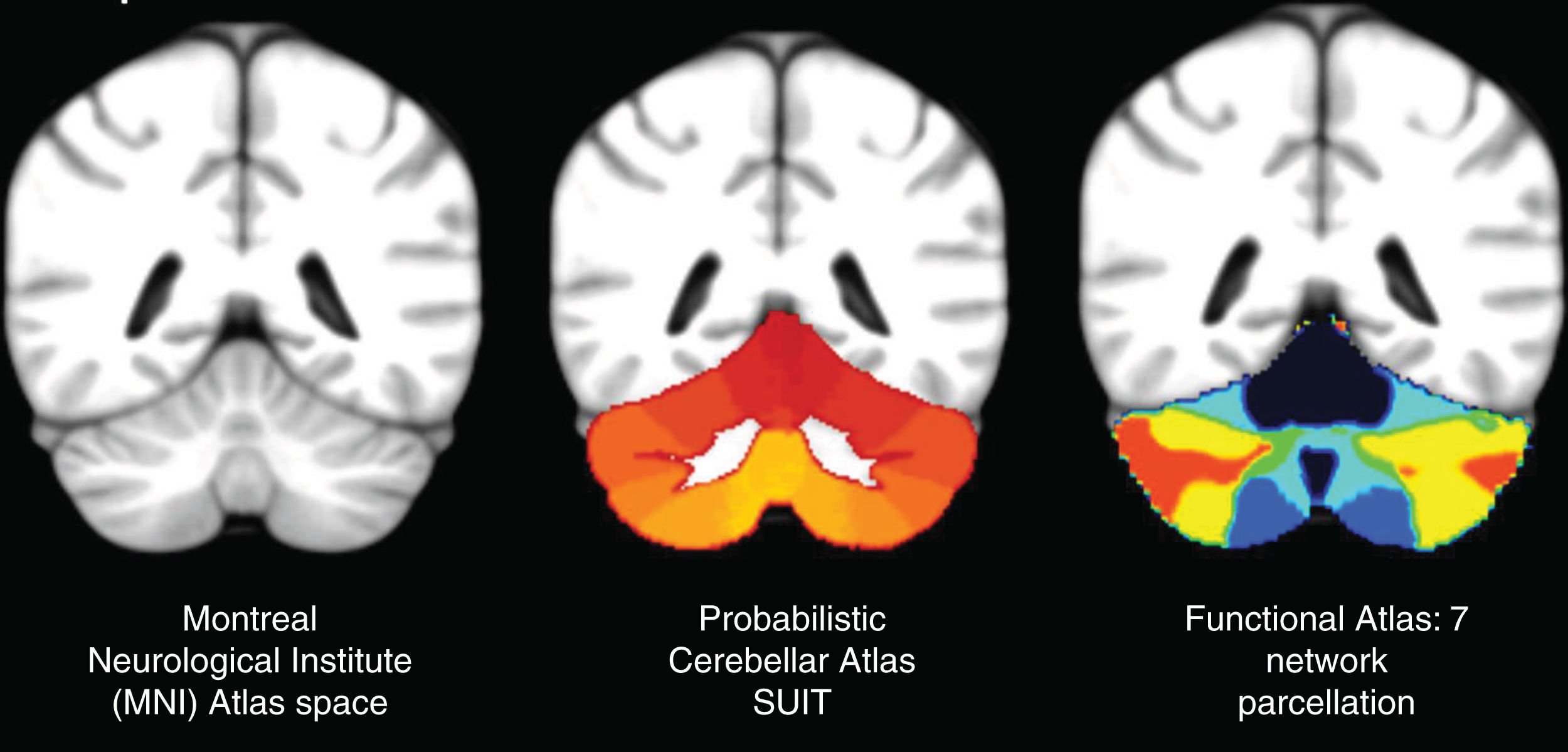

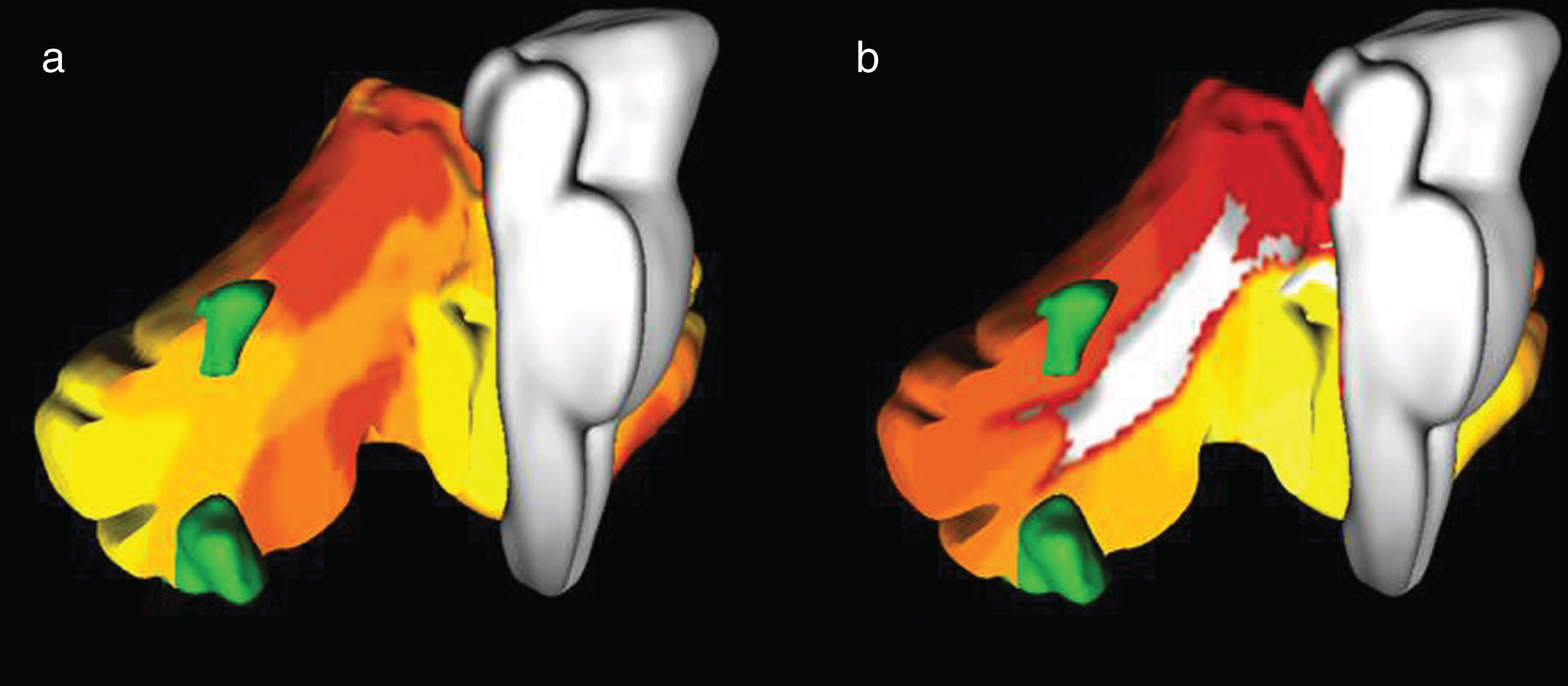

The images were converted from the DICOM format to NIFTI using the dcm2nii tool from MRIcro (McCausland Center, Columbia, SC). T1 sequences were processed using BET v2.1 (Brain Extraction Tool) to perform skull stripping using a fractional intensity threshold of FIT=0.5. The functional studies were processed using the FEAT v6.0 tool (FMRI Expert Analysis Tool), defining a cut-off value for the high-pass filter, taking into account the time period for each task. Motion correction was performed through the FLIRT tool (FMRIB's Linear Image Registration Tool), correction of the synchronisation of the cuts using the Fourier space, and spatial smoothing with a Gaussian kernel FWHM=7mm. An alignment with the structural sequence was carried out using a rigid body transform of 6 degrees of freedom using the BBR (Boundary-Based Registration) algorithm, and with the brain template of the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI152) using a related transform of 12 degrees of freedom. The activation maps were extracted with the tools of the FMRIB Software Library v5.0.8 (FSL, FMRIB Centre, Oxford, UK), carrying out a first level analysis. The statistical analysis of the time series was performed using FILM (FMRIB's Improved Linear Model) with local autocorrelation correction. A univariate analysis was performed based on the general linear model, establishing a single explanatory variable and a double gamma haemodynamic response function for convolution with the functional signal. The Z (Gaussianised T/F) statistical maps were obtained using clusters determined by Z>2.3 and a significance level of p=0.01. Subsequently, a high-level analysis was carried out using FLAME stage 1 (FMRIB's Local Analysis of Mixed Effects, FSL), including only the right-dominant subject group (n=23). The activations were described taking into account the Harvard-Oxford cortical and subcortical structural probabilistic brain atlas, created by the Harvard Centre for Morphometric Analysis. Cerebellar level activations were described taking into account the SUIT high resolution infratentorial and cerebellar probabilistic atlas,9–12 and the cortical parcellation estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity described by Yeo et al.13 (Fig. 3).

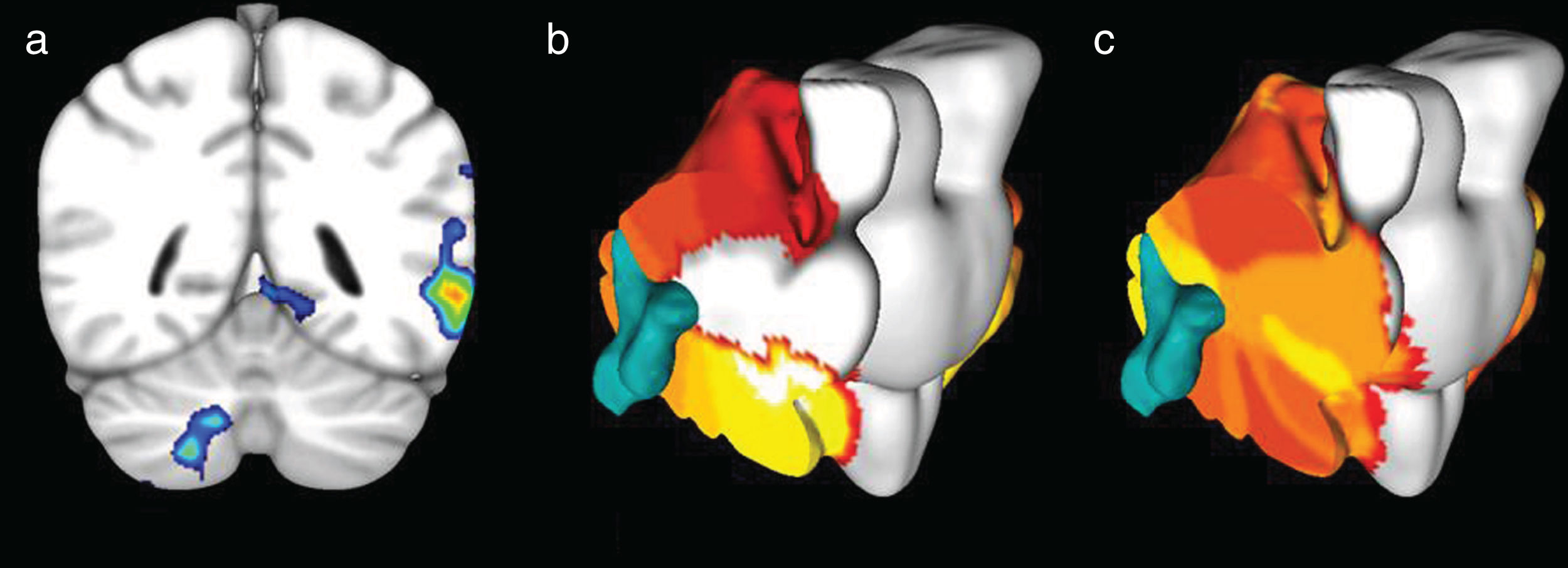

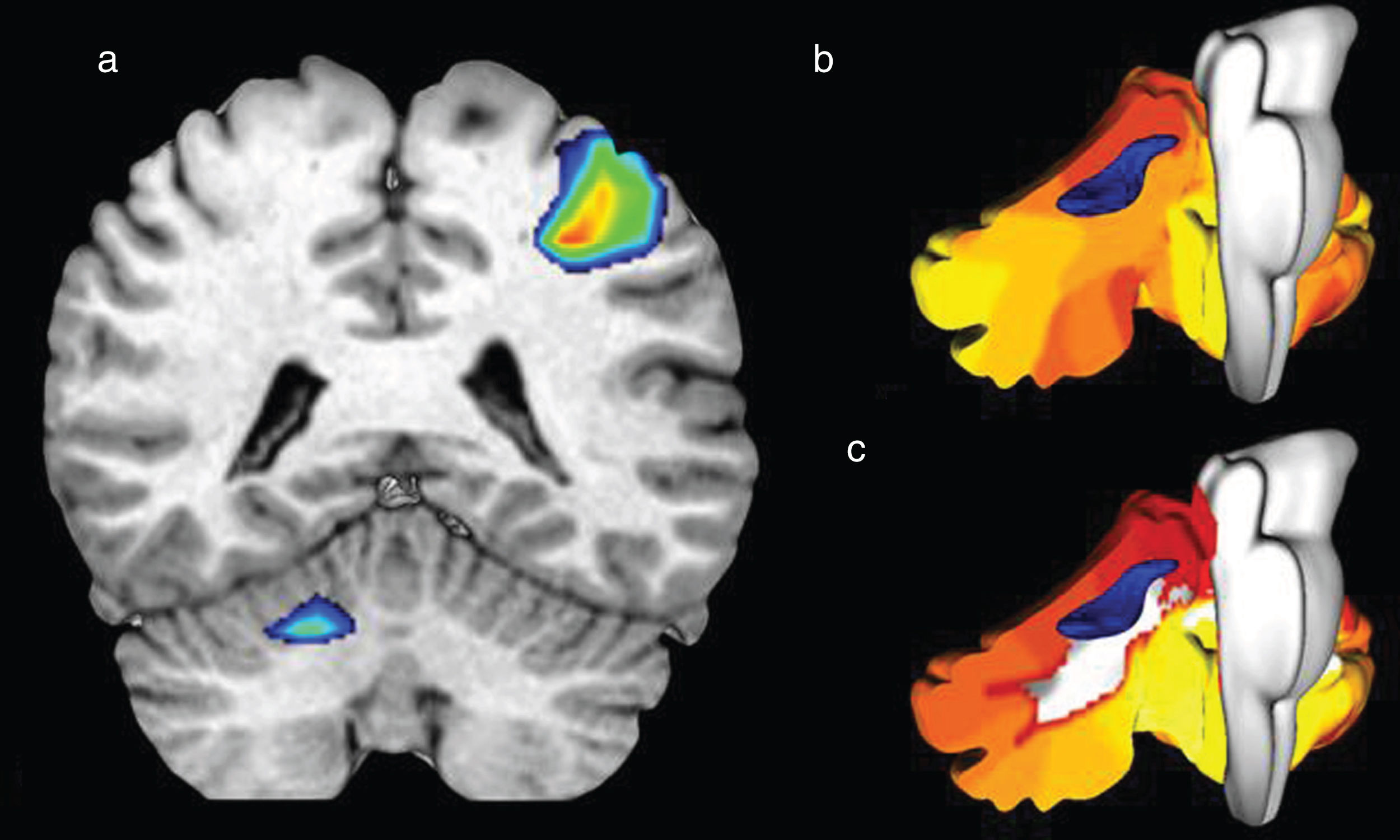

ResultsRight-dominant subjectsIn language tasks involving both productive and receptive components, at the supratentorial level, activation of the inferior frontal gyrus and of the angular, supramarginal and superior temporal gyri was observed in the left cerebral hemisphere associated with Broca's and Wernicke's areas, respectively, while in the cerebellum activation was observed in the right hemisphere of lobes Crus I, Crus II, VIIb and VIIIa, which correspond to the frontoparietal and dorsal and ventral attention networks (Fig. 4). In the receptive language task (mental reading of a story), activation of the angular, supramarginal and superior temporal gyri in the left cerebral hemisphere, associated with Wernicke's area, was evidenced, while at the infratentorial level, activation of cerebellar lobes VI, Crus I and Crus II was observed in the right hemisphere.

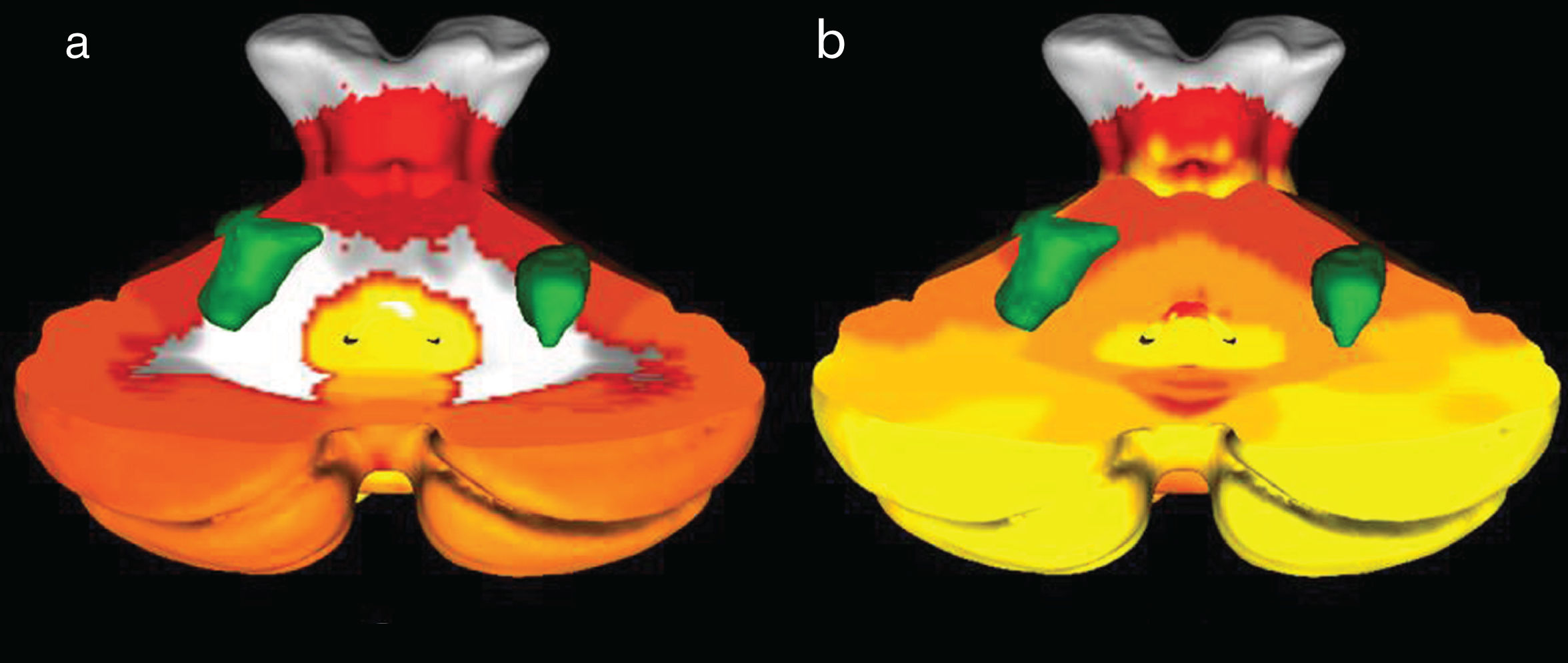

During the motor task, at the supratentorial level, activation of the pre- and post-central gyri was observed in the left hemisphere associated with the motor and sensory representation of the right upper limb. In the cerebellum, activation in the right hemisphere was observed in lobes V and VI, which correspond to the somatomotor and frontoparietal functional networks (Fig. 5).

Cerebral activation in the motor homunculus in the left hemisphere associated with the motor representation of the right upper limb (A), with contralateral activations at cerebellar level (A) in lobes V and VI (C), corresponding to the second functional network described by Yeo et al. (B), during motor tasks.

In scene coding tasks, supratentorial symmetric bilateral activation of the parahypocampal, fusiform and lingual gyri was observed, while at the infratentorial level, bilateral activation of cerebellar lobes V, VI and Crus I was observed in relation to the somatomotor functional networks and ventral attention networks (Fig. 6). On the other hand, during the execution of working memory tasks, activation of the prefrontal and parietal cortex was observed bilaterally and symmetrically. In the cerebellum, activation was observed in the right hemisphere of lobes VI, VIIb and VIIIa, corresponding to the dorsal and ventral attention networks and to the frontoparietal network (Fig. 7).

In receptive and productive language tasks, an activation pattern similar to that described in the group of subjects with right dominance was observed in one of the subjects. However, the other left-handed subject showed an activation pattern with dominance of the right cerebral hemisphere for receptive and productive language functions, observing activation of the inferior frontal gyri and the angular, supramarginal and superior temporal gyri in the right cerebral hemisphere, while In the cerebellum, activation was observed in the left hemisphere of lobes Crus I, Crus II, VIIb and VIIIa, which correspond to the frontoparietal and dorsal and ventral attention networks.

In motor tasks, supratentorially activation of the pre- and post-central gyri was observed in the right hemisphere associated with the motor and sensory representation of the upper left limb, while in the cerebellum, activation was observed in the left hemisphere in lobes V and VI that correspond to the somatomotor and frontoparietal functional networks.

In scene coding and working memory tasks, the activation pattern was similar to that of the group of subjects with right dominance, both supra- and infratentorially.

DiscussionTopographical differentiation of the regions of cerebellar activation has allowed us to characterise the different clinical signs and symptoms that occur in the pathologies in this region.4 Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is a useful tool to anatomofunctionally differentiate regions of the cerebrum and cerebellum; some studies of fMRI currently focus on checking and distinguishing topographic areas from different domains.1 In this study, the functional activation pattern and its anatomical relationship during the execution of motor, language and memory tasks were described in the cerebellum.

Motor areasDifferent studies show that motor tasks are located in the anterior lobe with secondary representation in lobes VIII and IX.1,14,15 These findings correlate with the clinical manifestations of patients with cerebral motor syndrome, where the anterior cerebellar lobe is compromised.1,16 Although this type of case does not discriminate between the types of motor tasks, other published studies show that those tasks that require greater sensorimotor coordination with sequential repetitive movements are represented in a different cerebellar area, lobes VI and VIIa.17 In our study, the motor task activated cortices V and VI, regions related to the movement of the upper limbs in the sensorimotor homunculus of the cerebellum. These findings correlate with what is observed in the scientific literature.4,16–19 Synchronous motor activation in the cerebellum has a hemispheric location contralateral to cerebral activation. The relationship between both activations is believed to be linked to the preparation, execution and coordination of the movement.1,20 In our case series, both right-dominant and left-dominant subjects achieved cerebellar activation contralateral to activation in the supratentorial cortex.

Productive and receptive language areasThe lateralisation of language in the cerebellum depends on the cerebral dominance for language. That is why, in most people, language tasks activate right cerebellar lobes VI and VII.8,14,21 In this case series, a block paradigm design is used to discriminate between receptive and productive language tasks. In the receptive language task we found activation of cerebellar lobes VI, Crus I and Crus II; in the productive language task, activation of cerebellar lobes Crus I, Crus II and VIIb was found. Some studies suggest that receptive language tasks have hemispheric activation, while language production tasks activate vermial and paravermial regions.8 The cerebellum seems to be involved in the semantic, phonetic and grammatical associations of language.8,22 The cerebellum is part of the motor component of the language network, which also involves the inferior frontal gyri, the anterior insula, the premotor cortex and the caudate nucleus. Some authors believe that the role of the cerebellum in this network is related to verbal fluency and the structuring of phonation.8,23

Working memory regionsIn our study, the activation of the cerebellum during working memory tasks shows the same activation pattern as for language tasks.14,24 The activation of lobes VI, VII and VIII, with right cerebellar predominance, may be related to the phonological component in working memory.14,25 Some authors also claim that the activation of the lateral component in lobes VI and Crus I during working memory is related to planning and preparation (the central executive component of working memory) and lobes Crus II and VIII are related to the auditory and visual information processing necessary for these tasks.26–28

ConclusionsLesions in the cerebellum have a varied spectrum of clinical manifestations. Recent advances in neuroimaging have allowed a better understanding of the anatomy, function and connectivity of the cerebellum. However, much remains to be known and understood about cerebellar activation and its pathways of connection with the cerebral cortex, especially in relation to non-motor cognitive functions. Knowledge of the normal patterns of activation through fMRI can be useful for the radiologist and the clinician in their approach to patients with a varied spectrum of pathologies with cerebellar involvement.

Authorship- 1.

Responsible for the integrity of the study: AMG.

- 2.

Study conception: AMG, JFO, GPBC, SYRT.

- 3.

Study design: AMG, JFO.

- 4.

Data acquisition: JFO, GPBC, SYRT.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: AMG, JFO, GPBC, SYRT.

- 6.

Statistical processing: AMG, JFO.

- 7.

Literature search: AMG, JFO, GPBC, SYRT.

- 8.

Drafting of the article: AMG, JFO, GPBC, SYRT.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: AMG, JFO, GPBC, SYRT.

- 10.

Approval of the final version: AMG, JFO, GPBC, SYRT.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez-Takeuchi SY, Baena-Caldas GP, Orejuela-Zapata JF, Granados Sánchez AM. Análisis del patrón de activación funcional del cerebelo y su correlación topográfica. Radiología. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rx.2019.11.009