Male nipple discharge is uncommon and highly associated with malignancy. However, it can also be due to benign processes. In addition to physical examination, all patients should undergo a radiological examination with mammography and/or ultrasound. Furthermore, we propose the use of contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM) in cases of suspicious nipple discharge due to the high negative predictive value of this technique, potentially reducing the number of unnecessary biopsies. The aim of this article is to review the imaging findings of the most common causes of male nipple discharge, both benign and malignant. Additionally, we would like to share our experience with the use of CEM in studying this condition.

La secreción mamaria en el varón es infrecuente y se encuentra altamente asociada a malignidad. Sin embargo, también puede ser debida a procesos benignos. Además de la exploración física, todos los pacientes se deben realizar un examen radiológico con mamografía y/o ecografía. Además, nosotros proponemos el uso de la mamografía con contraste en los casos de secreción mamaria sospechosa dado el alto valor predictivo negativo de esta técnica, lo que permite reducir el número de biopsias innecesarias. El objetivo de este artículo es realizar una revisión de los hallazgos por imagen de las causas más frecuentes de secreción mamaria en el varón tanto benignas como malignas. Asimismo, nos gustaría compartir nuestra experiencia con el uso de la mamografía con contraste en el estudio de esta patología.

Nipple discharge is an uncommon complaint in men,1,2 not well-documented in the literature.1,3 However, due to its strong association with underlying malignancy,1 it should always be radiologically further evaluated. Approximately 14% of male patients with breast cancer experience nipple discharge, typically serosanguineous in nature.2 In male patients, sanguineous nipple discharge is associated with carcinoma in 50%–75% of cases, which is three times higher than the risk found in women.2 Awareness of this clinical symptom by clinicians, patients, and radiologists may aid in the early detection of cancer, leading to improved survival rates.3

Although a high proportion of male patients presenting with nipple discharge have underlying malignancy such as invasive ductal carcinoma, ductal carcinoma in situ, papillary carcinoma or Paget disease, approximately 43% have a benign cause for their nipple discharge.3 Some of these benign causes include gynecomastia, mammary duct ectasia, papillomas, abscesses, and fibrocystic changes.

The aim of this article is to review some of the most common benign and malignant causes of male nipple discharge registered at our center.

Normal male breastMale breast is a rudimentary structure that consists of adipose tissue, a few subareolar ductlike structures a small nipple-areolar complex and a prominent pectoralis muscle.4,5

In contrast to the female breast, ductal system is involuted due to increase in testosterone levels, terminal ductal-lobular unit is rare due to the lack of progesterone, stromal system is smaller in size, pectoralis muscles are more prominent and cooper ligaments are absent.4

Mammographically, the male breast appears as homogenously radiolucent fat tissue with a prominent pectoralis muscle.4,5 Sonographically, it appears as isoechoic fat lobules.5 MRI of male breast has limited use.4

Workup of male nipple dischargeThe low positive and negative predictive value of physical breast examination suggests that male patients with nipple discharge should undergo a radiological examination.2 Conventional techniques (mammography and ultrasound) are useful in the first evaluation of nipple discharge with a higher predictive negative value than physical examination.2 Günhan-Bilgen et al. emphasized the importance of mammography and ultrasound in the evaluation of male breast conditions, along with physical examination.6

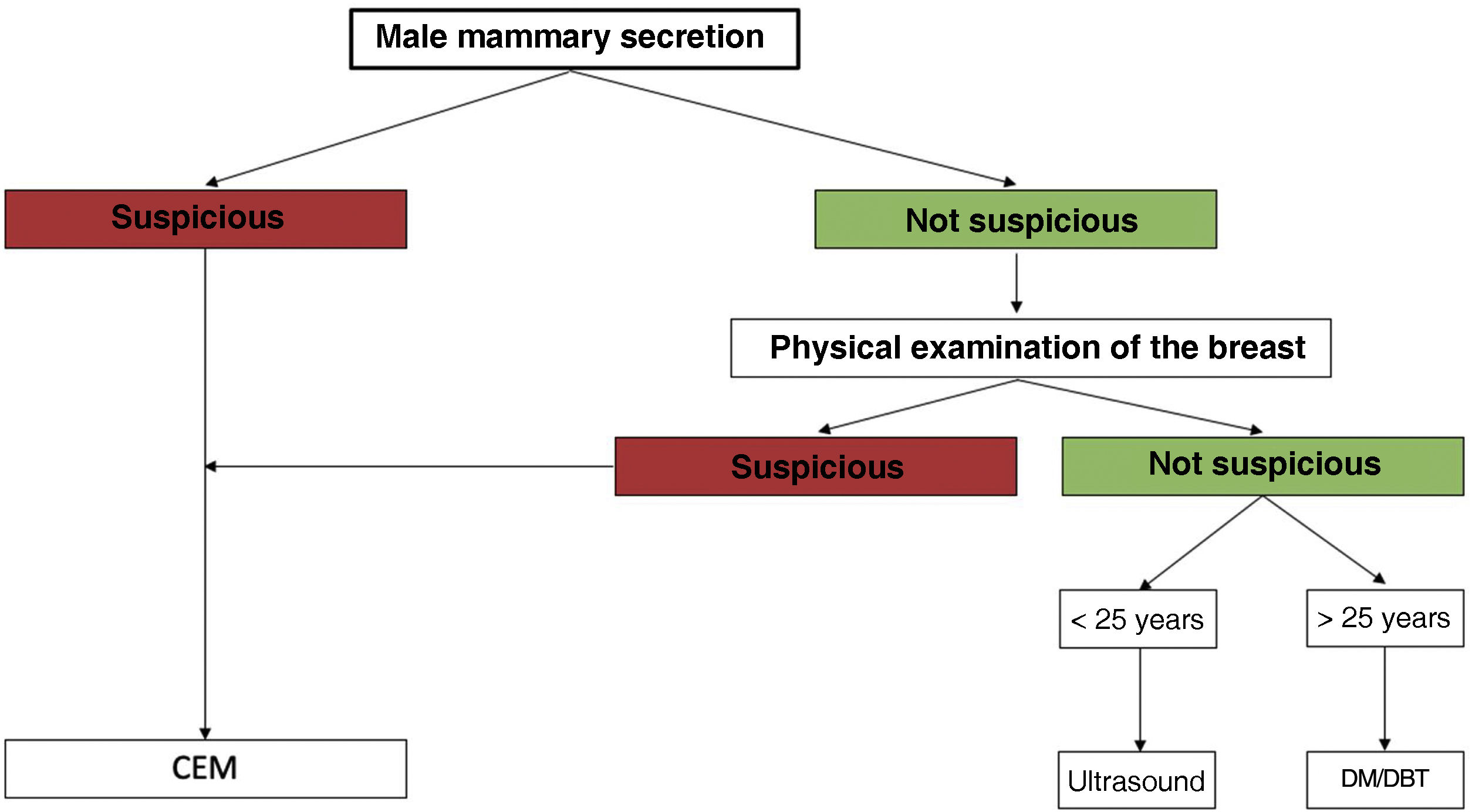

There is no accepted consensus for diagnostic imaging algorithm of the male breast.4 The ACR criteria suggest an age limit of 25 years old for first-line imaging modality. Below 25 years old, ultrasound is recommended as the first-line imaging, whereas after 25 years old, mammography is suggested.4

Since its approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2011, CEM has emerged as a new functional technique.7 Although not yet described in the literature we have found that the use of CEM could significantly impact the approach to male nipple discharge. CEM has shown a higher sensitivity and negative predictive value than mammography or ultrasound,7–9 potentially reducing unnecessary biopsies.

Even though a clinical-radiological approach is fundamental in male nipple discharge, definitive diagnosis relies on pathological assessment either with nipple fluid cytology, fine needle aspiration cytology, or core biopsy of a mass.3 However, cytological examination is only useful when positive, and can have a false-negative rate for cancer of up to 50%.1

At our institution, in cases of suspicious male nipple discharge and non-suspicious male nipple discharge with a pathological breast examination, the first-line imaging technique is CEM. In cases of non-suspicious male nipple discharge with a normal breast examination we follow the ACR criteria. Therefore, below 25 years old ultrasound is performed and above 25 years old mammography is the first-line imaging (Fig. 1). When a doubtful finding is seen on mammography or ultrasound, CEM is considered as a problem-solving tool. In the absence of morphologically suspicious lesions or pathological enhancements on CEM, BIRADS 2 may be assessed.

In the flowchart for women with pathologic nipple discharge, it is recommended to perform an MRI after negative results from diagnostic breast imaging (mammography and ultrasound).10 In our opinion, CEM could be a valuable alternative for men.

Benign entitiesGynecomastiaGynecomastia is the most common cause of a male breast lump4 and the most prevalent benign condition affecting the male breast.11 It involves the enlargement of the male breast due to benign stromal and glandular proliferation,11 and is commonly observed during pubertal period or senescence.4 Clinically, gynecomastia may be detected as a palpable, discrete area of subareolar tissue,6 which has generally persisted for months.11 In some cases, it can be accompanied by nipple discharge.2 Gynecomastia tends to be bilateral 5 and has a central symmetric location under the nipple.11 The etiology of gynecomastia includes physiological, endocrinological, metabolic, neoplastic, and drug-induced factors.4

Apart from gynecomastia related to Klinefelter’s syndrome,1 there is no association between gynecomastia and male breast cancer.12

The differential diagnosis for gynecomastia includes pseudogynecomastia (breast enlargement caused by fatty tissue without glandular or stromal involvement) and malignancy.4 Mammography has proven to be an accurate method for distinguishing between benign gynecomastia and breast carcinoma.11,13 In fact, a mammographic diagnosis of gynecomastia does not require tissue confirmation.13

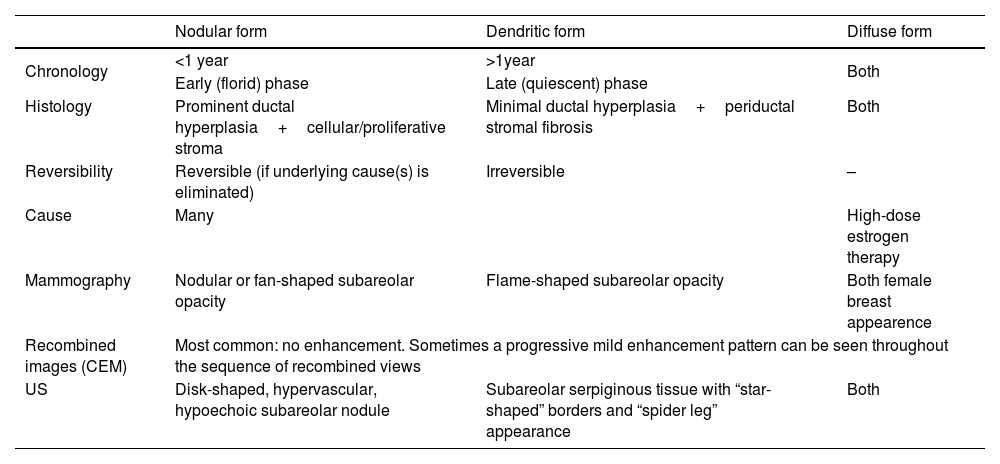

There are three mammographic patterns of gynecomastia4 (Table 1), which represent different degrees and stages of ductal and stromal proliferation.11

Gynecomatia patterns.

| Nodular form | Dendritic form | Diffuse form | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronology | <1 year | >1year | Both |

| Early (florid) phase | Late (quiescent) phase | ||

| Histology | Prominent ductal hyperplasia+cellular/proliferative stroma | Minimal ductal hyperplasia+periductal stromal fibrosis | Both |

| Reversibility | Reversible (if underlying cause(s) is eliminated) | Irreversible | – |

| Cause | Many | High-dose estrogen therapy | |

| Mammography | Nodular or fan-shaped subareolar opacity | Flame-shaped subareolar opacity | Both female breast appearence |

| Recombined images (CEM) | Most common: no enhancement. Sometimes a progressive mild enhancement pattern can be seen throughout the sequence of recombined views | ||

| US | Disk-shaped, hypervascular, hypoechoic subareolar nodule | Subareolar serpiginous tissue with “star-shaped” borders and “spider leg” appearance | Both |

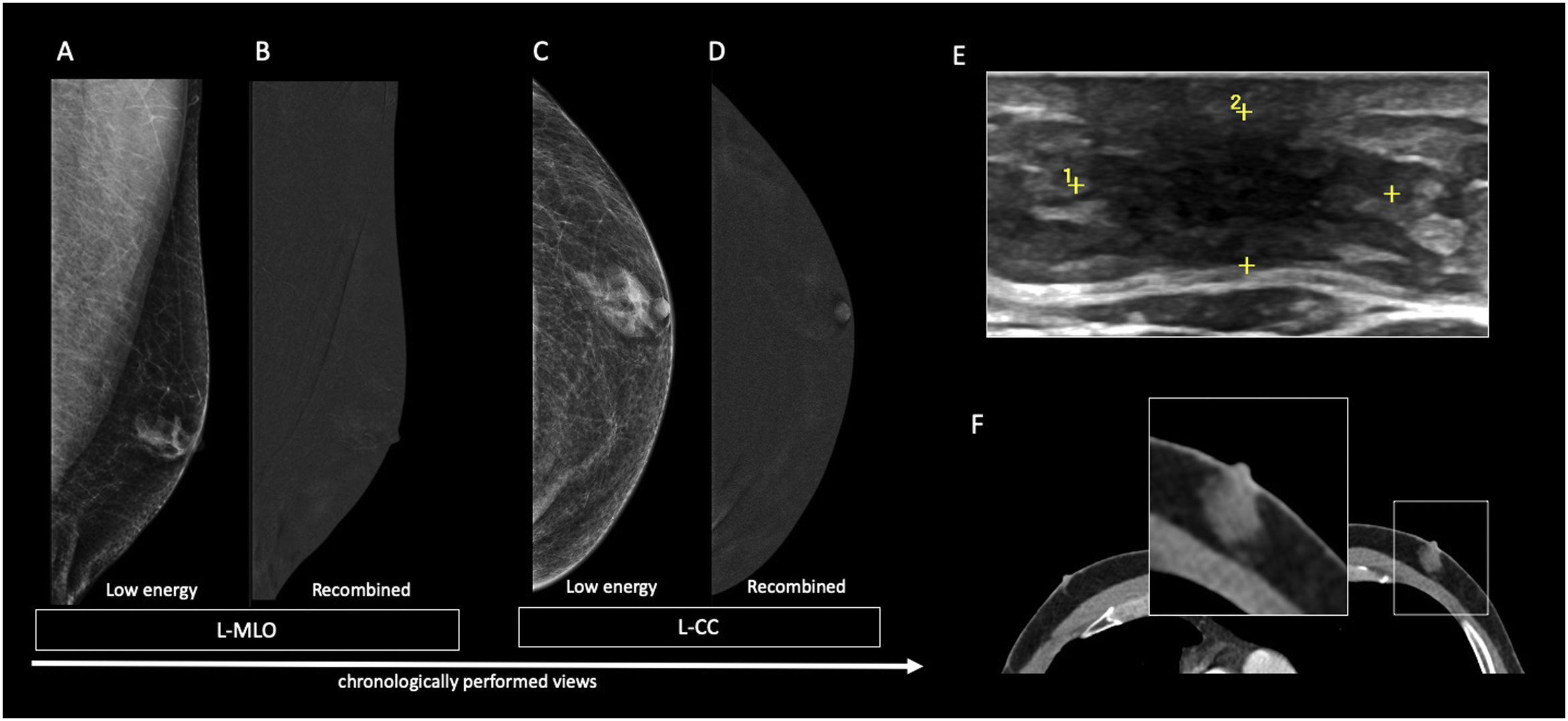

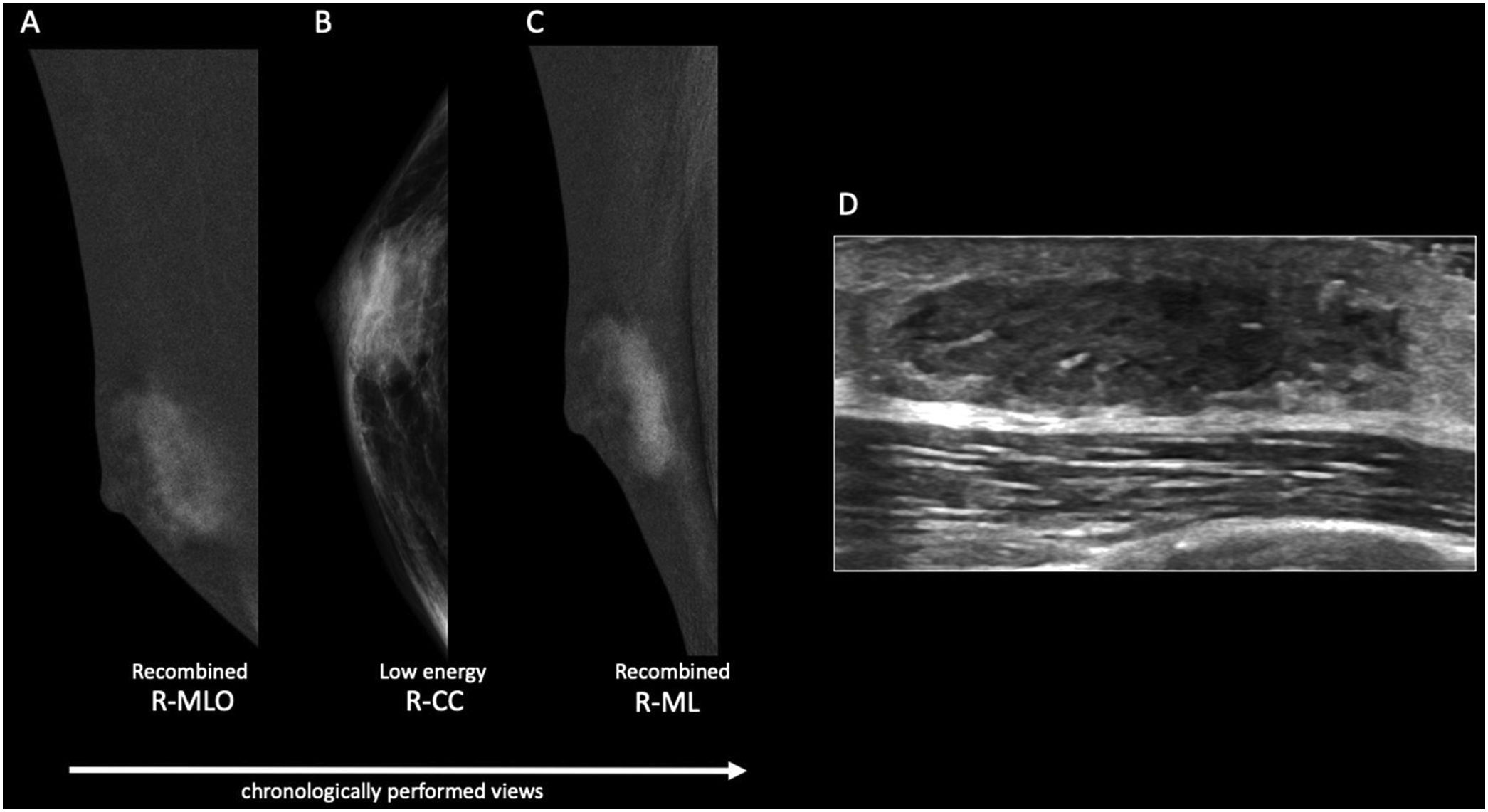

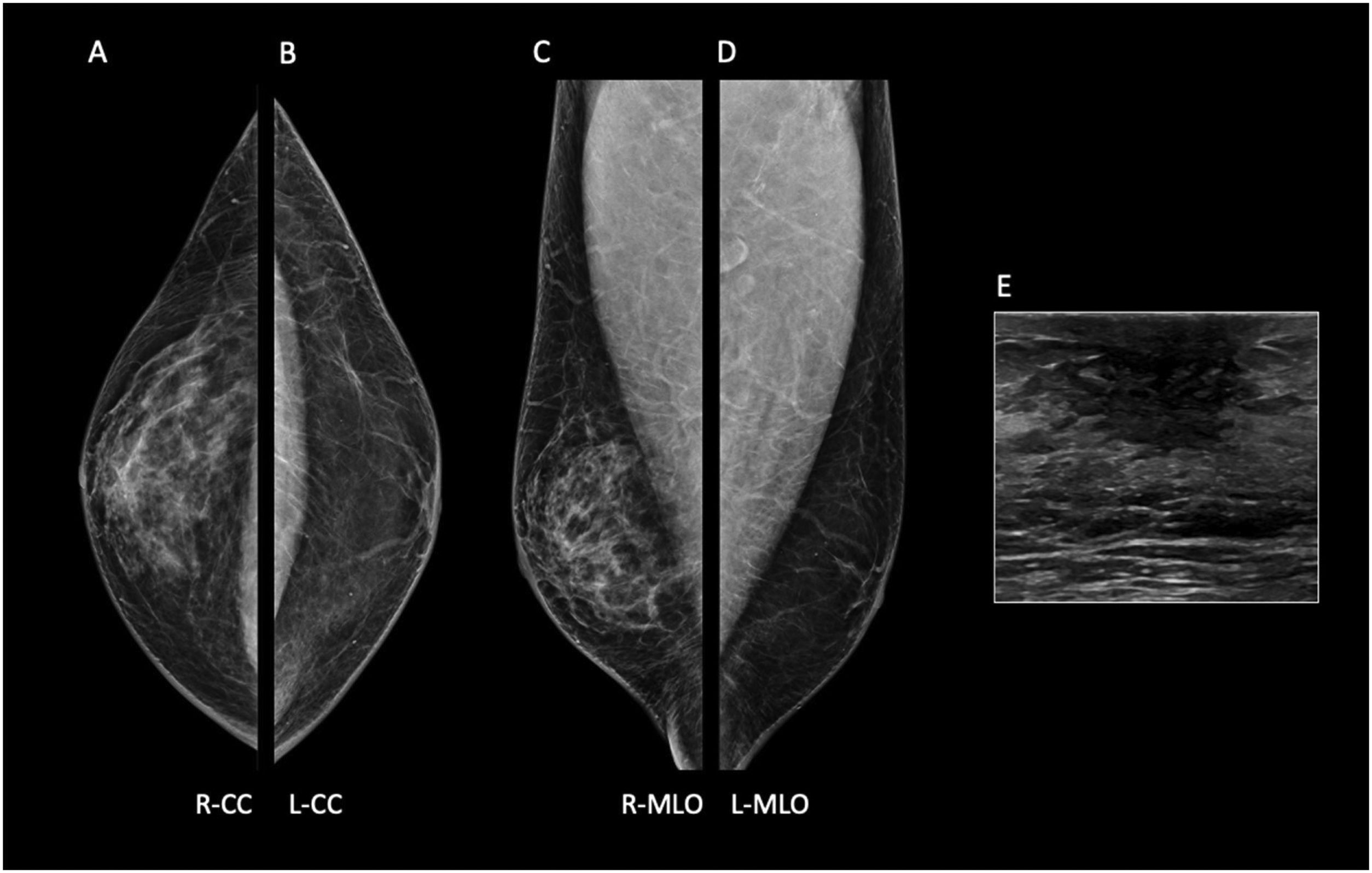

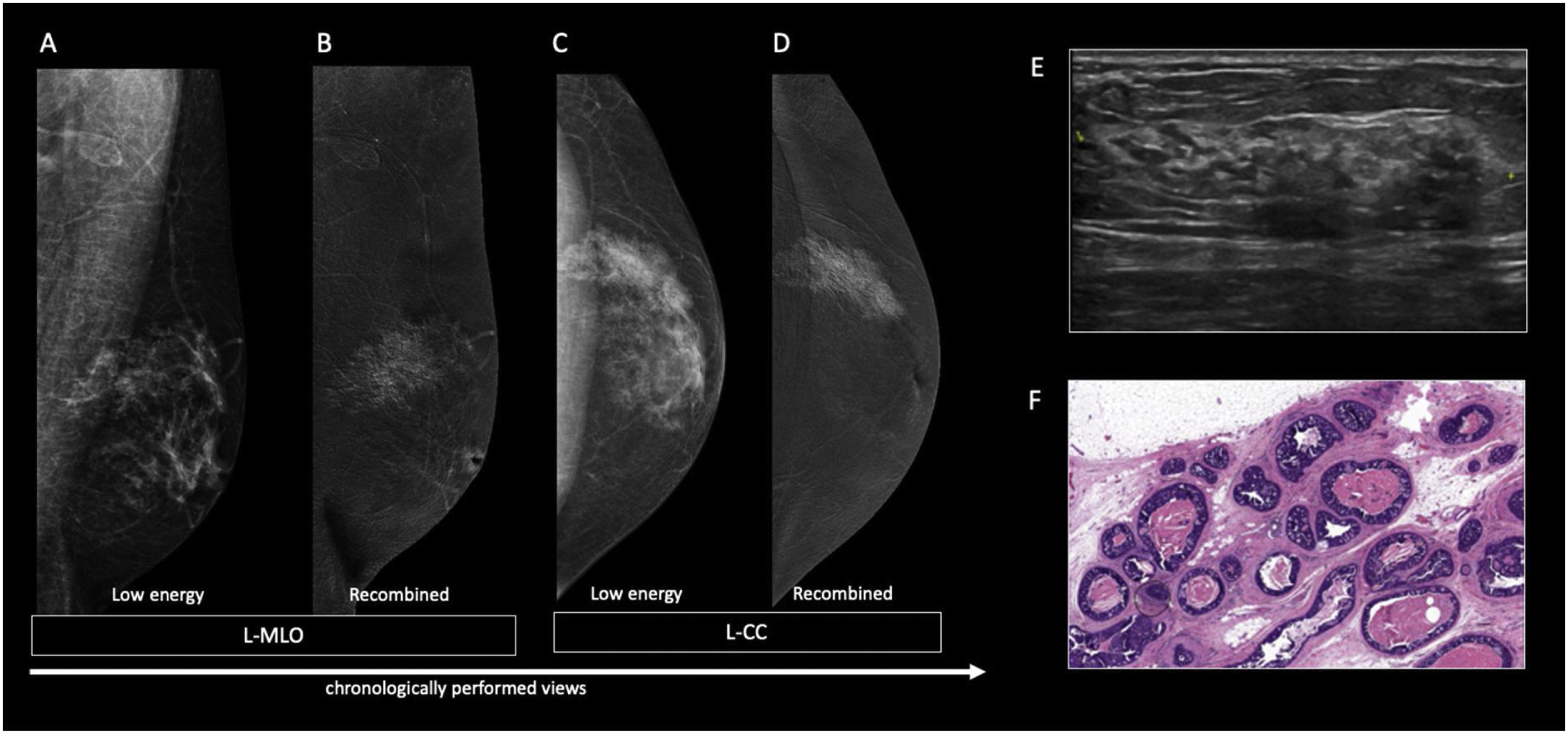

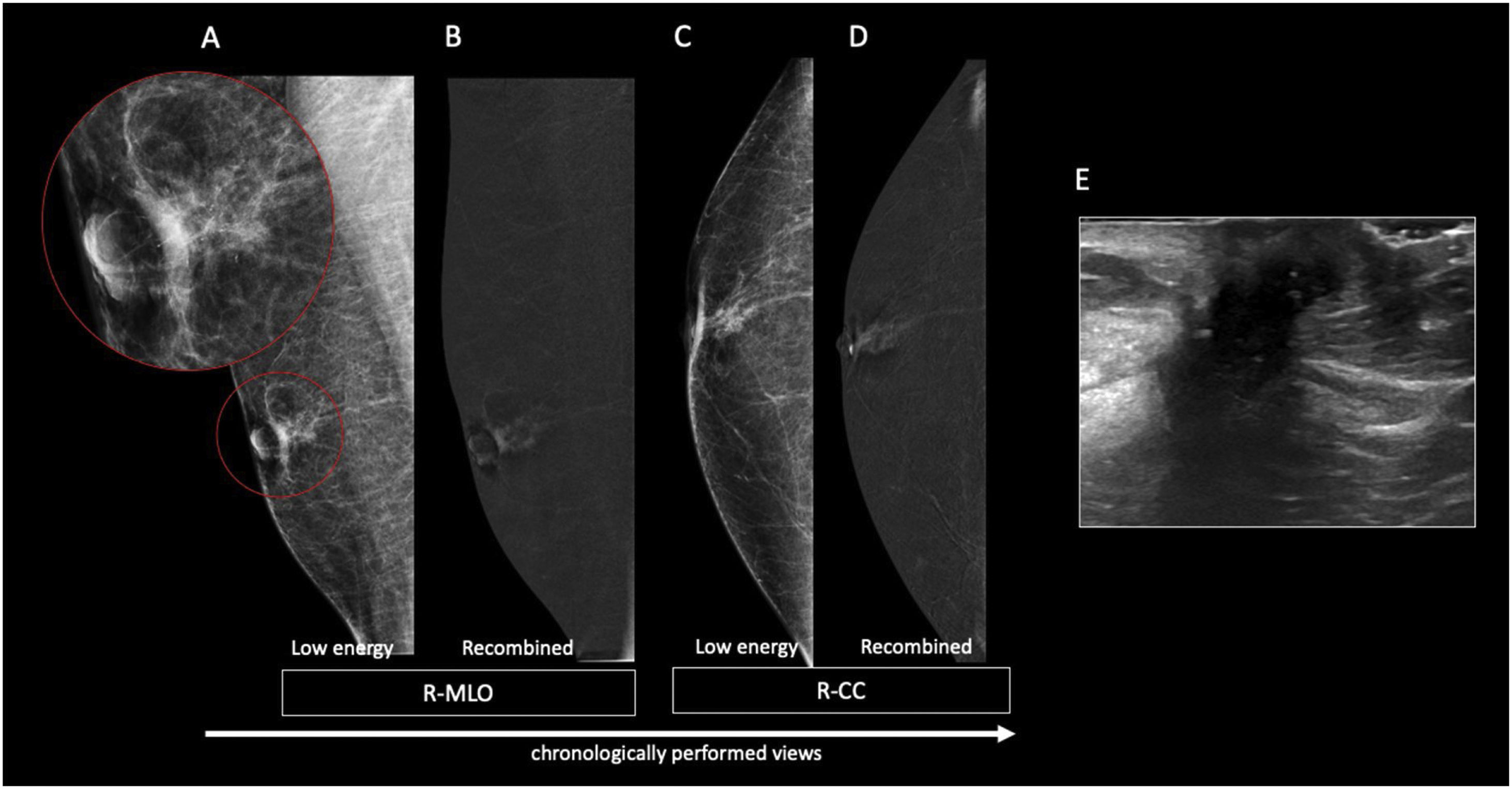

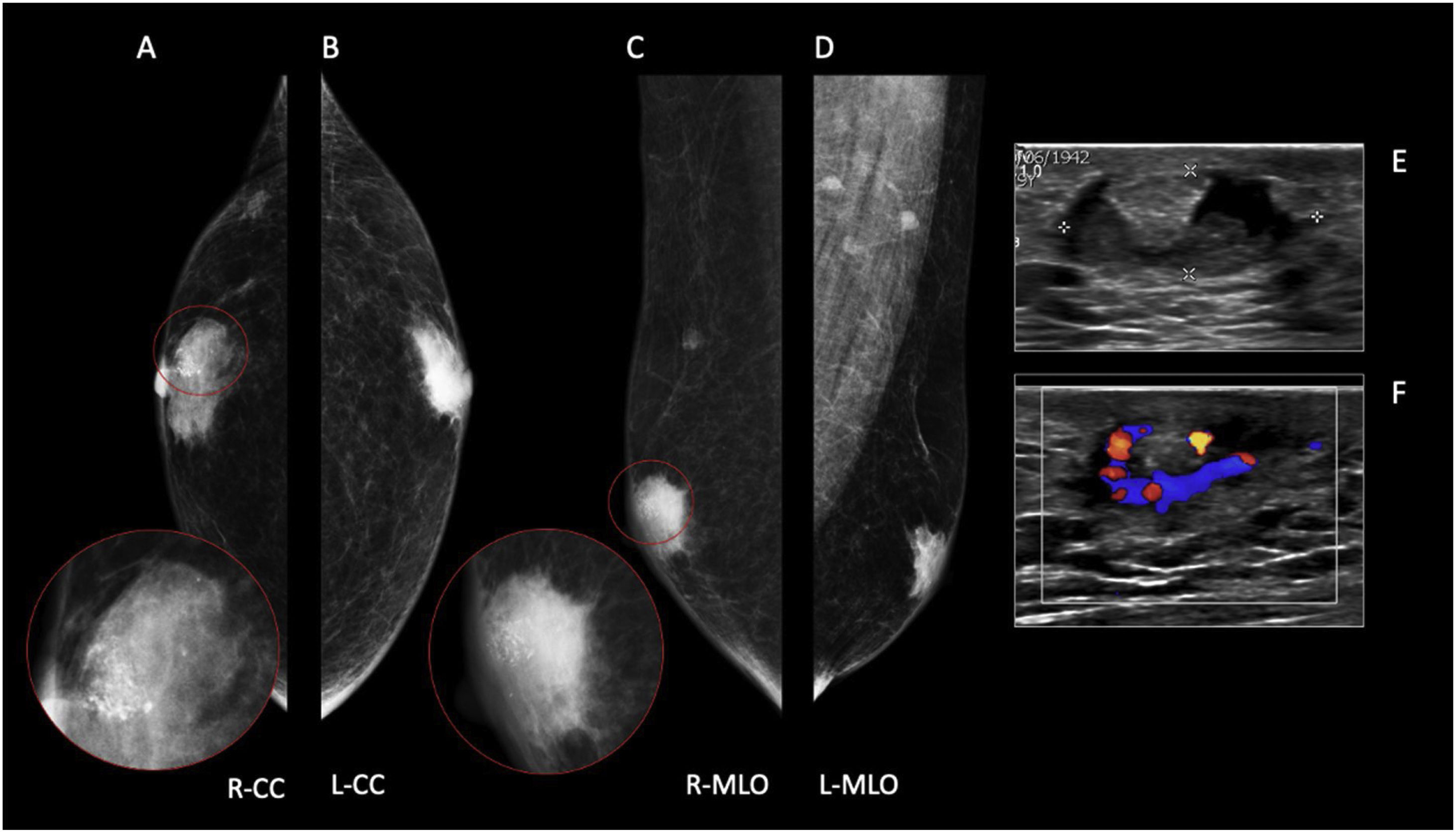

The nodular form is seen in patients with gynecomastia for less than 1 year.11 It is often referred as the early florid phase. Histologically, nodular gynecomastia is characterized by prominent ductal hyperplasia and cellular/proliferative stroma.4 It is worth noting that nodular gynecomastia is reversible if the underlying cause(s) is eliminated.4 Mammographically, it manifests as a nodular or fan-shaped subareolar opacity.4 On ultrasound, it appears as a disk-shaped, hypervascular, hypoechoic subareolar nodule surrounded by breast tissue 4,11 (Figs. 2 and 3).

60 year-old men with personal history of lung cancer presented with a left retroareolar lump and clear ipsilateral nipple discharge. On the low energy images (A, C), a nodular left subareolar opacity is seen. On the recombined images (B, D), it shows no enhancement. Sonographically (E), it corresponds to a hypoechoic subareolar nodule surrounded by breast tissue. Asymmetrical gynecomastia is also evident on CT images (F). Findings are suggestive of nodular pattern gynecomastia.

60 year-old male, HIV positive, presented with a right retroareolar mass and clear nipple discharge. No lymphadenopathies on physical exam. On the low energy right CC image (B), a nodular subareolar image can be seen. On the recombined images (A, C), a progressive mass enhancement is depicted. Note the increased in conspicuity at the last performed view (R-ML). On ultrasound (D), a hypoechoic subareolar nodule surrounded by breast tissue is shown. A 14G core needle biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of nodular gynecomastia.

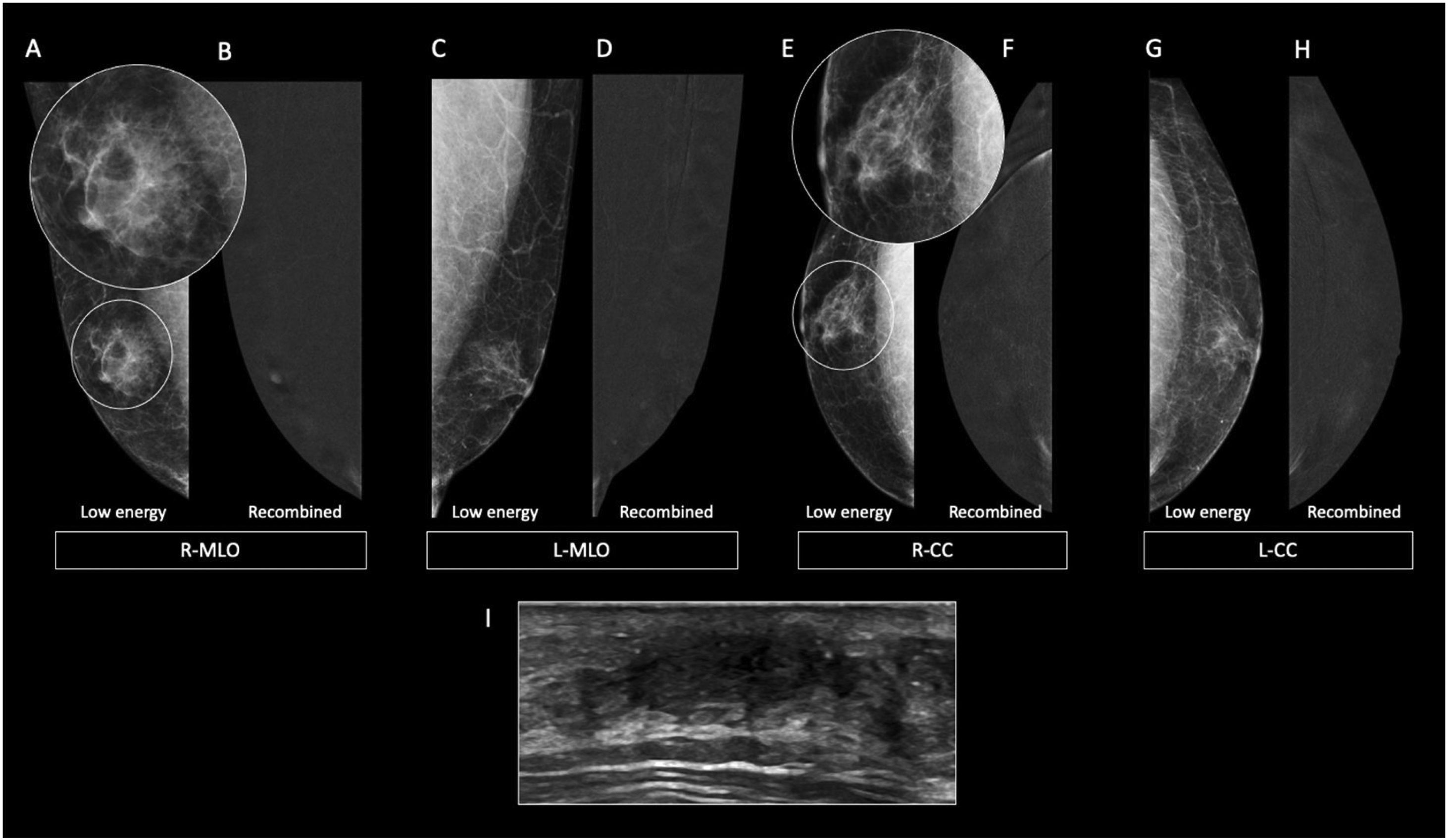

The dendritic form is seen in patients with gynecomastia for longer than 1 year.11 It is often referred as the late quiescent phase. Histologically, it is characterized by minimal ductal hyperplasia and periductal stromal fibrosis.4 In this form, fibrosis becomes the dominant process rendering the dendritic form of gynecomastia irreversible.11 Mammographically, it presents as a flame-shaped subareolar opacity4 with posterior linear projections radiating into the surrounding tissue towards the upper-outer quadrant11 (Fig. 4). On ultrasound, it presents as a subareolar serpiginous tissue with “star-shaped” borders and “spider leg” appearance.4,11

64-year-old male diagnosed with Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) who underwent surgery in his childhood for prolactinoma. Breast examination showed bilateral subareolar tissue. On the low energy images (A, C, E, G), a flame-shaped subareolar opacity is seen. On the recombined images (B, D, F, H), it exhibits no enhancement. The ultrasound of the right retroareolar region (I) shows a hypoecoic area with “star-shaped” borders.

In some cases, patients with gynecomastia may experience an acute episode in addition to the presence of chronic dendritic gynecomastia. As a result, both the acute and chronic phases can be observed simultaneously.11

Diffuse formThe diffuse form of gynecomastia has properties of both early and late phases.4 It is commonly associated to high-dose estrogen therapy4,11 and is frequently observed in transgender individuals undergoing hormone treatment.4 Mammographically, the diffuse form presents as heterogeneously enlarged breast tissue, resembling a female breast appearance4 (Fig. 5). It displays a diffuse density with both dendritic and nodular features.11 On ultrasound, nodular and dendritic features are seen surrounded by diffuse hyperechoic fibrous breast tissue.11

52 year-old male presented with increased density and mastalgia of the right breast, as well as clear nipple discharge. On DBT (A–D) bilateral asymmetrical gynecomastia can be seen. On the right breast (A, C) the fibroglandular tissue simulates a dense female breast (diffuse gynecomastia) while on the left breast (B, D) only sparse fibroglandular tissue, mainly at the subaeolar region, is seen.

Based on our experience with CEM, gynecomastia typically does not exhibit enhancement on the recombined images (Figs. 2 and 4). However, in some cases, a progressive mild enhancement pattern may be observed (Fig. 3). CEM is particularly valuable in distinguishing the nodular form of gynecomastia from malignancy when there is clinical suspicion. If no enhancement is detected, biopsy can most likely be avoided.

Mammary duct ectasiaMammary duct ectasia is a benign condition characterized by the presence of dilated ducts, often occurring in the subareolar region.14 It is accompanied by periductal fibrosis and inflammation.14,15 Within the dilated ducts, debris and secretions can accumulate, and may calcify.4 The exact cause of mammary duct ectasia remains uncertain,14 and its association with smoking remains controversial.15 Mammary duct ectasia is rare in men.14,15

On physical examination, common findings of mammary duct ectasia include nipple discharge, a subareolar tender breast mass, and nipple retraction.4,15

Common mammographic findings are subareolar ductal dilatation with intraductal calcified secretions, and coexistent mass-like opacities in subareolar location.4 The most commonly reported US findings of mammary duct ectasia include dilated ducts and tubular anechoic lesions that may contain echogenic debris within the subareolar region14 (Fig. 6).

AbscessA breast abscess is defined as an inflammatory mass that drains purulent material spontaneously or on incision. The most common cause of a breast abscess is mastitis, which is less often reported in men compared to women.16 Other potential causes include surgery, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, among others. Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis are the most commonly identified causative organisms.17 Subareolar abscess, also known as, “Zuska’s disease,” is considered a specific type of abscess in subareolar location caused by aseptic inflammation due to squamous metaplasia secondary to obstruction of lactiferous ducts.4 The clinical presentation of a breast abscess includes pain, warmth, redness, induration, palpable mass, and nipple discharge.17 Treatment options involve antibiotic therapy and percutaneous ultrasound-guided drainage.17 Adequate follow-up is essential to ensure complete resolution.18 Although extremely rare, it is important to consider the possibility of malignancy presenting as an abscess.18

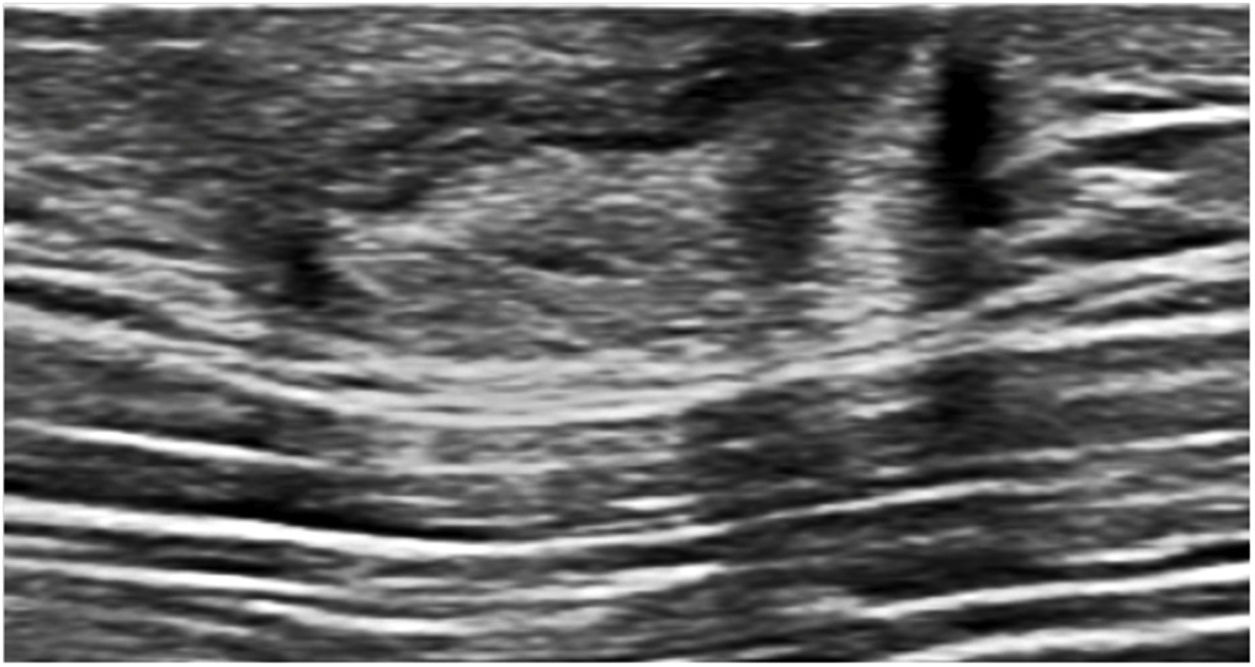

Ultrasound is considered the most useful imaging modality for evaluating breast abscesses. It is valuable to monitor progress, response to therapy and to ensure resolution. Sonographically, it normally presents as a “heterogenous, irregular, hypoechoic mass” (Fig. 7) or as a “fluid collection with internal echoes, and irregular walls.” The surrounding tissues may exhibit increased vascularity with sparse to absent internal flow.17 Thickening of skin due to inflammation, and fistulous tract formation may also be present.4

53-year-old male with a history of subcutaneous right mastectomy due to abscessed gynecomastia in 2020, presented with pain, erythema and purulent discharge after the intervention. The ultrasound exam shows findings suggestive of cellulitis with a retroareolar fluid collection with irregular walls (abscess) on the right mastectomy bed. A fistulous tract in the external periareolar area was also seen during the breast scan (not shown on the image).

Mammography is difficult to perform due to pain with breast compression.4 However, when feasible, mammographic findings of a breast abscess may include skin thickening, distortion, an ill-defined subareolar mass, and trabecular thickening.4

Malignant entitiesMale breast cancer is relatively rare, accounting for approximately 0.5%–1% of all reported breast cancers and less than 0.1% of male cancer deaths.5 The overall prognosis for men is less favorable than for women, primarily due to delayed detection. The most common clinical presentation is a centrally located, firm, painless mass. Other clinical presentations include nipple retraction and nipple discharge.5 Various risk factors have been described, with the most prevalent being increasing age, often attributed to testicular malfunction and elevated estrogen levels. Other risk factors include a family history of breast cancer, mutations in breast cancer genes (BRCA2>BRCA1), Cowden and Klinefelter syndromes (Fig. 8), alcohol consumption, liver disease,19 hyperestrogenism, and a history of chest irradiation.17

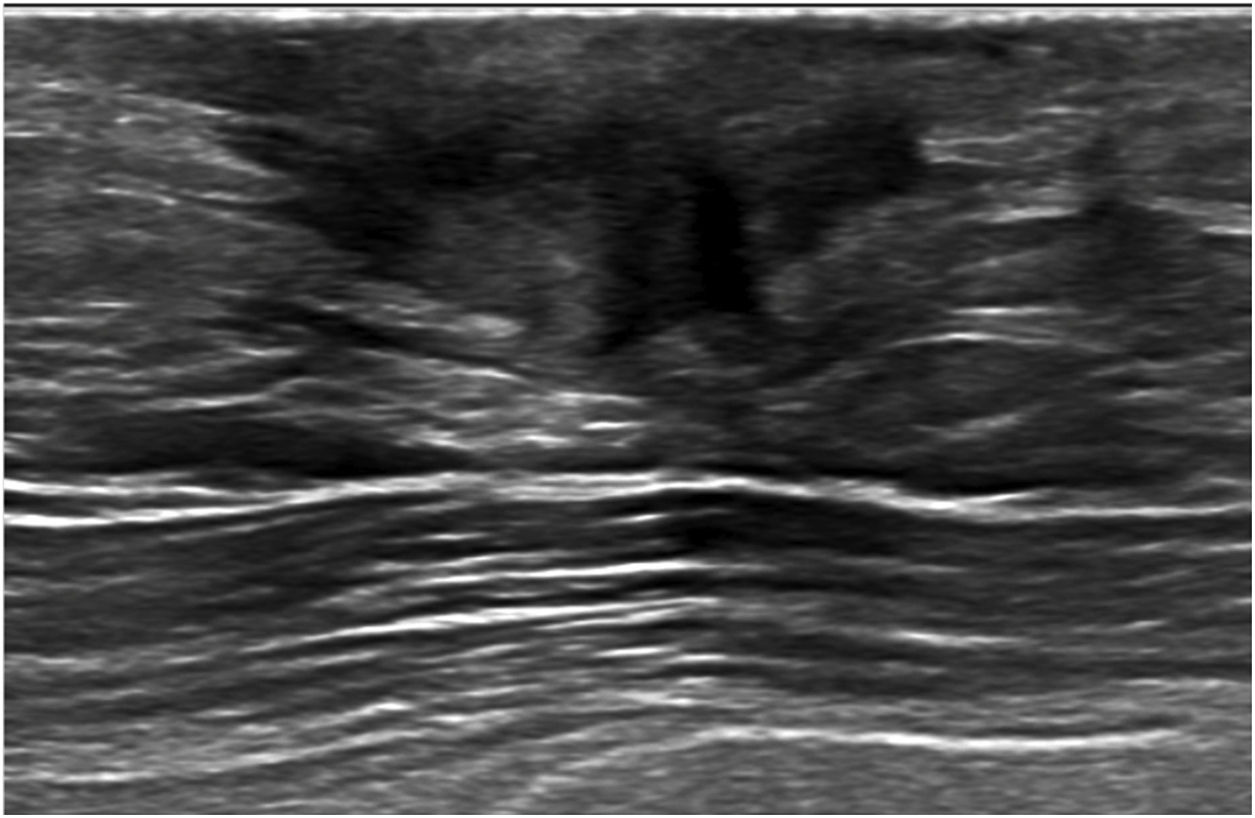

56-year-old male diagnosed with Klinefelter’s syndrome presented with long standing pain in the left breast and sudden ipsilateral sanguineous nipple discharge. On Digital Mammography (A–D), a focal asymmetry with fine pleomorphic grouped calcifications is seen at the left internal retroareolar region (B, D). On ultrasound (E), an area of duct ectasia with a solid mass and associated calcifications (white arrow) is shown. 14G core needle biopsy proved DCIS. Histology after mastectomy confirmed pure DCIS with no invasive component.

Ductal carcinoma of the male is rare and is usually associated with invasive carcinoma.19,20 Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of the male breast represents less than 0.1% of all cancers in men.19 When the in situ component is present in pure form, the histological grade is normally low to intermediate.19 The most common histological subtype of DCIS in males is papillary carcinoma.19,20

The most common presenting sign is a slowly growing subareolar mass.20 It may be accompanied by breast pain, nipple discharge, or nipple retraction.19 Nipple discharge on its own is an uncommon form of presentation.1

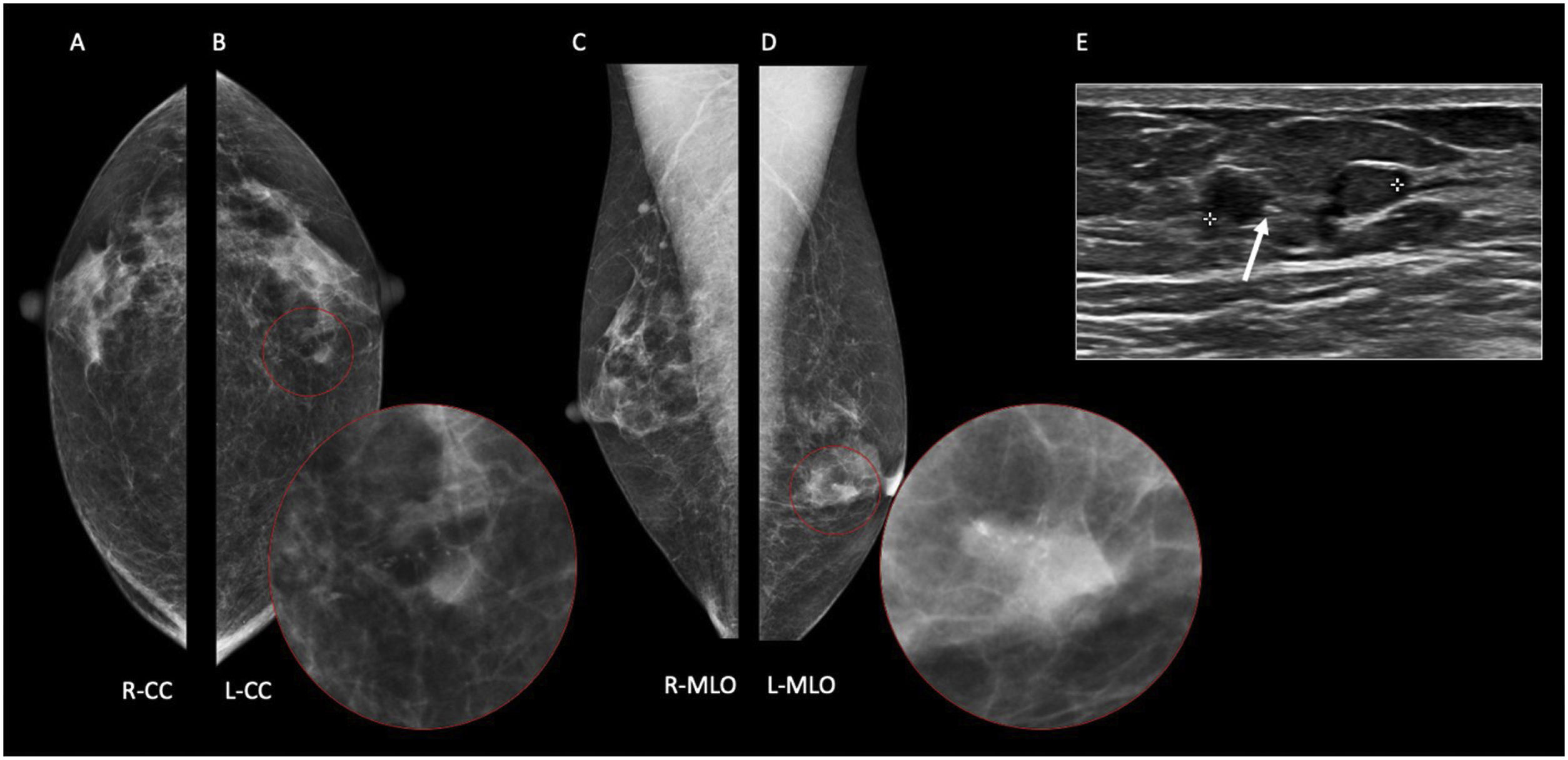

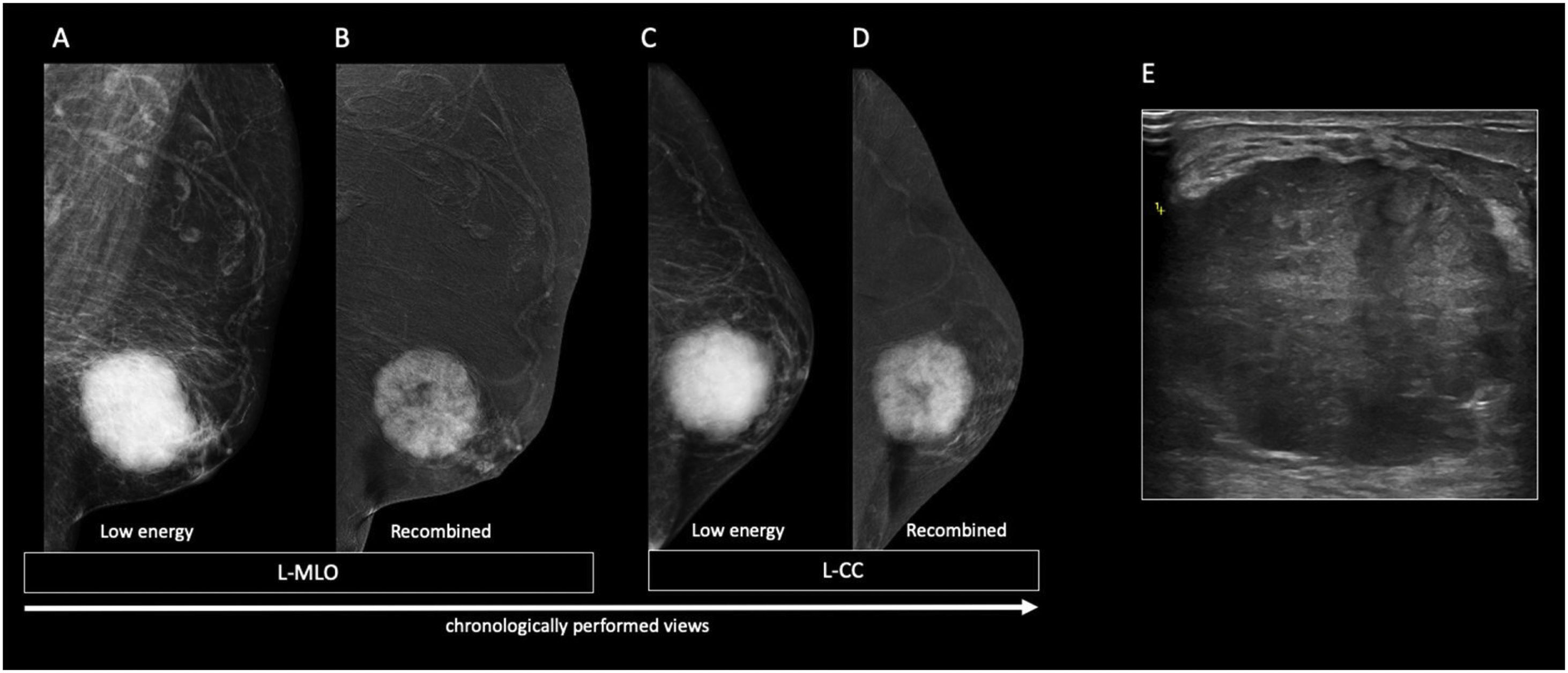

In males with gynecomastia, detecting DCIS on mammography can be challenging.19 Microcalcifications are seen less likely in male breast cancers, possibly due to the involuted ductal structure.4 When present, these calcifications often have a benign or nonspecific appearance 19 (Fig. 8). Additionally, if invasive carcinoma is present, parenchymal opacity or distortion may be seen.4 DCIS normally presents a non-mass enhancement on the recombined images of CEM (Fig. 9).

47-year-old male presented with left breast growth for 5 months and unilateral clear discharge. On the low energy images (A, C), a focal asymmetry of the entire upper-external quadrant of the left breast with associated diffuse calcifications are seen. On the recombined images (B, D), a segmental non-mass enhancement is observed. Sonographically (E), the lesion corresponds to a heterogeneous mass. 14G core needle biopsy proved DCIS (F). Histology after mastectomy confirmed pure DCIS with no invasive component.

The findings on ultrasound for DCIS in males are non-specific and not well-documented in the literature. However, coexistent invasive ductal carcinoma foci may be visualized as a mass or distortion.4

Invasive ductal carcinomaInvasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) of no special type is the most common type of male breast carcinoma, accounting for approximately 85% of cases.11,21 Unlike in women, the male breast rarely develops terminal ductal-lobular units,4,20 making lobular carcinoma very uncommon.1 The nipple tends to be affected earlier in men, due to the development of the tumor below the nipple, where rudimentary breast ducts are located.22 Nevertheless, eccentric location can occur and is highly suspicious for cancer.11 Bilateral carcinoma is less frequent in men (1,9%) compared to women (4,3%).22

It typically presents as a hard, painless, palpable mass that may be accompanied by secondary features such as nipple retraction, skin thickening, palpable axillary lymphadenopathies4 and nipple discharge.

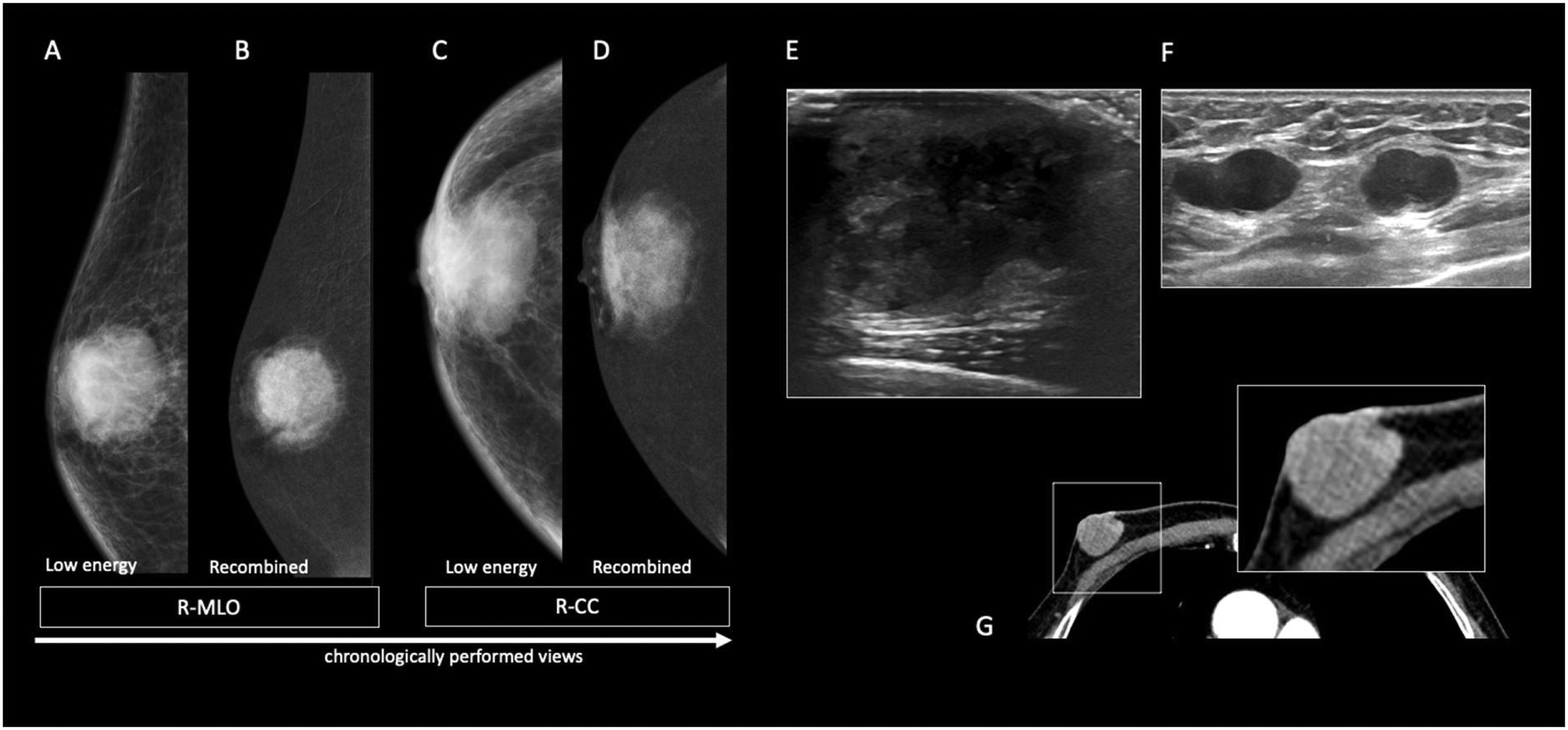

A common mammographic presentation of IDC of the male is as high-density irregular mass with well-defined contours and spiculated, lobulated, or microlobulated margins 4,11 (Figs. 10 and 11). The incidence of calcifications is lower than in female breast cancer.4,11 Bilateral mammography is recommended in case of malignity suspicion since the risk factors that predisposed the emergence of the disease in one breast have acted similarly in the contralateral breast.4,22,23 It normally presents a mass enhancement on the recombined images of CEM (Figs. 10 and 11).

71 year-old man with right nipple retraction, pain and sanguineous uniorificial discharge. On the low energy images (A, C), a right retroaerolar irregular mass with not-circumscribed margins that affects the nipple-areolar complex is seen. On the recombined images (B, D), it shows as a heterogeneous mass-like enhancement. Sonographically (E), it corresponds to a heterogeneous solid lesion with irregular shape and not-circumbscribed margins that invades the nipple-areolar complex. 14G core needle biopsy demonstrated IDC.

70 year-old man presented with a long standing retroareolar palpable mass. On breast exam sanguineous nipple discharge and right axillary lymphadenopathies were also noted. On the low energy images (A, C), a dense irregular right retroareolar mass with not-circumscribed margins and infiltration of the nipple-areolar complex is seen. On the low energy images (B, D), it presents as a heterogeneous mass enhacement. Sonographically (E), it corresponds to a solid irregular heterogeneous lesion. Two BEDI-6 (replacement of the fatty hilum) adenopathies are seen at Berg’s level 1 of the right axilla (F). 14G core needle biopsy proved IDC. Fine needle aspiration of both adenopathies was positive for malignancy.

Male breast cancers have similar ultrasound features as in women.5,11 They most commonly present as non-parallel, discrete, hypoechoic masses with irregular margins and variable vascularity that may be accompanied by secondary features.4,11 US of the axillary region should be a routine part of evaluation because up to 50% of males with breast cancer present with axillary lymphadenopathies.4,11 (Fig. 11).

Papillary carcinomaPapillary carcinoma is the second most frequent histological subtype of male breast cancer.24 It accounts for approximately 4% of breast carcinomas in men.24 In terms of gender distribution, papillary carcinomas are more common in men compared to women, with a ratio of 2–1.4 Papillary carcinoma represents 5% of breast carcinomas in men vs 1%–2% of breast carcinomas in women.5

Cysts in the male breast must be considered suspicious for malignancy11 and intracystic papillary carcinoma should be taken into account.5 Papillary carcinoma in men is more common than benign intraductal papilloma.5 Therefore, complete surgical excision and histopathologic evaluation of the lesion are required.5 Most male papillary carcinomas are intracystic and noninvasive.5 Clinically, most reported male patients with papillary carcinoma present with a breast mass or swelling, sometimes accompanied by nipple discharge.24

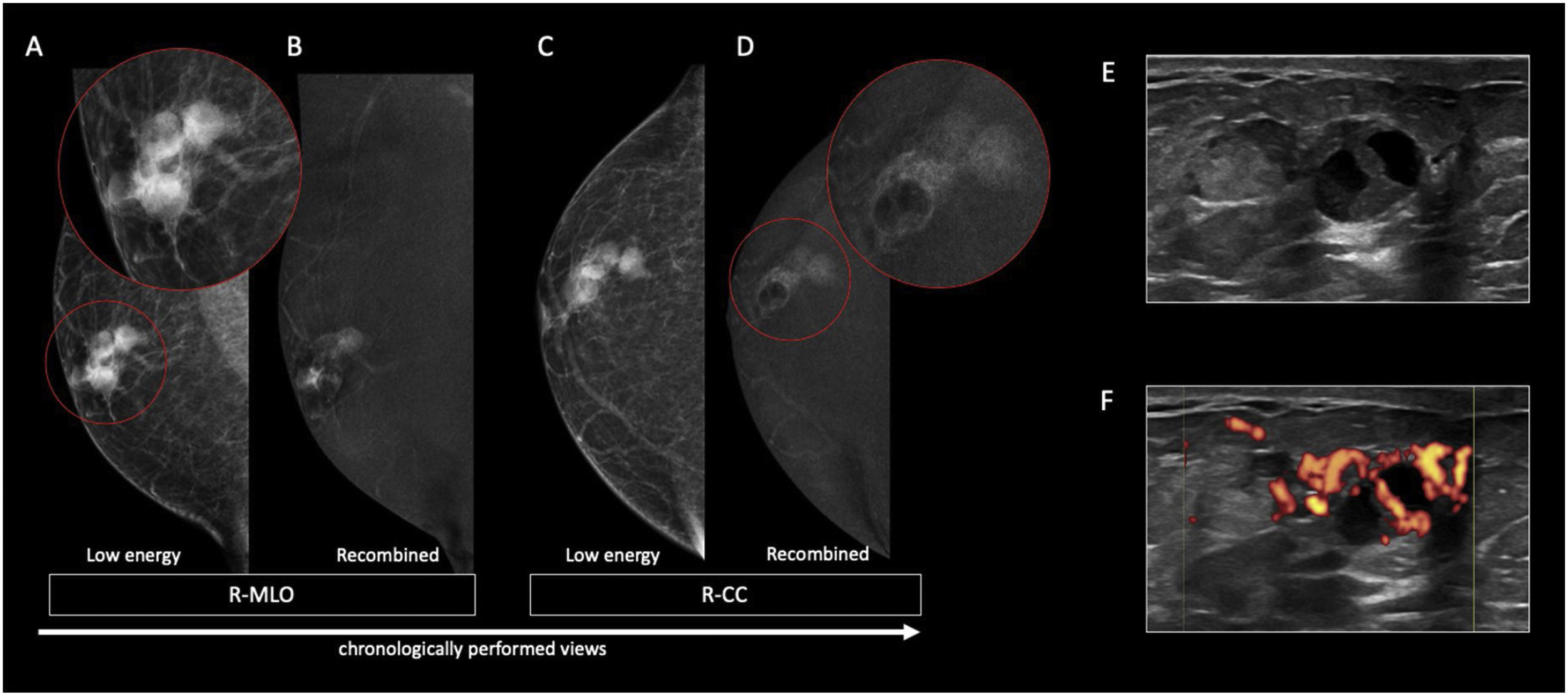

On mammography, papillary carcinoma typically presents as a circumscribed round/oval mass5 (Figs. 12 and 13). The presence of focal poorly defined borders may indicate the presence of an invasive component.5 Although rare, satellite nodules and microcalcifications can also be observed5,25 (Fig. 13). On the recombined images of CEM, papillary carcinoma may present as a mass with rim enhancement of the cyst walls, septa, and mural nodules (Fig. 12).

70 year-old male presented with a right retroareolar mass and unilateral sanguineous nipple discharge. On the low energy images (A, C), at the right external periareolar region, 3 adjacent dense rounded masses with circumscribed margins are observed. On the recombined images (B, D), they show heterogeneous mass enhancement. Central areas without enhancement relate to the cystic components of the lesions. Sonographically (E), they correspond to solid-cystic nodules with peripheral Doppler vascularization (F). 14G core needle biopsy confirmed invasive papillary carcinoma.

79-year-old male presented with a right retroareolar lump and right unilateral uniorificial bleeding (9 o’clock) to breast examination. On digital mammography (A–D), a right retroareolar dense mass with an oval shape and not-circumbscribed margins is seen (A, C). Note the presence of coarse heterogeneous calcifications within the mass. On ultrasound (E), the lesion corresponds to a solid-cystic mass, with areas of increased Doppler signal (F). 14G core needle biopsy showed papillary carcinoma.

Sonographically, it appears as a solid mass or a complex cystic mass with thick walls containing both solid and cystic components 5,26 (Figs. 12 and 13). Additionally, a hypoechoic nodule may be seen along the wall of the cyst 25 (Figs. 12 and 13).

Mucinous carcinomaInvasive mucinous carcinoma is a specific histological variant of breast carcinoma characterized by the presence of extracellular mucin surrounding neoplastic cells.4 Invasive mucinous carcinoma represents 1% of male breast cancers.4 Mucinous carcinoma is histopathologically subclassified into pure and mixed types depending on the mucinous content of the carcinoma.21,27 The pure form is defined as a lesion with a mucinous carcinoma component of over 90% of the tumor, while the mixed type is defined as having mucinous and conventional invasive ductal carcinoma components.21 It is well-established that pure mucinous carcinoma is generally associated with low rates of recurrence and excellent survival outcomes.21

Pure mucinous carcinoma is characterized by a higher volume of mucin, slower growht rate, a more benign clinical course and less frequent axillary node involvement.27,28

Physical examination is typically non-specific, a palpable hard subareolar mass may be seen.4 In our case, the patient presented with a doubtful serous nipple discharge. To our knowledge, this is the first case in the literature in which a mucinous carcinoma presented with nipple discharge.

Mammographically, pure mucinous carcinoma normally presents as a round, microlobulated, and well-circumscribed lesion 27,28 (Fig. 14). An indistinct margin favors the diagnosis of mixed mucinous carcinoma.28 On the recombined images of CEM it normally presents as a mass enhancement.

78 year-old man presented with a long-term palpable lump, that he related to a trauma and sanguineous nipple discharge in the left breast. On the low energy images (B, D), at the left retroareolar region, a dense mass with rounded morphology and microlobulated margins is seen. On recombined images (B, D), it appears as a heterogeneous mass-like enhancement. Sonographically (E), it corresponds to an isoechogenic mass, with a rounded morphology and microlobulated margins with little Doppler vascularization.

Sonographically, pure mucinous carcinoma often has well-defined margins. The tumor tends to appear isoechogenic relative to the fat surrounding the breast tissue (Fig. 14). In contrast, hypoechoic masses with an irregular shape are more suggestive of mixed mucinous carcinomas.27,28

According to some authors, the presence of a homogenous mass with both cystic and solid components, vascularity, and peripheral enhancement should raise a strong suspicion of pure mucinous carcinoma.28 Peripheral enhancement is likely a result of the high water content and the transmission of the ultrasound beam through the mucin.27 Therefore, it is more frequently observed in cases of pure mucinous carcinoma.

ConclusionNipple discharge can be caused by both benign and malignant processes. The presence of nipple discharge in a male may herald an underlying malignancy, the detection of which in its early stages, may confer a survival benefit with improved outcomes to the patient.1 However, the low suspicion of breast cancer, both among patients and doctors, has often resulted in delayed diagnoses.12

Besides physical breast examination, all male patients with nipple discharge should undergo a radiological examination.2 Conventional techniques (mammography and ultrasound) are useful in the first evaluation of nipple discharge. CEM has shown the highest negative predictive value8,9 of all tecnhiques potentially reducing unnecessary biopsies.

Although further studies are needed, we believe that CEM could be potentially used in the setting of male nipple discharge as a problem-solving tool especially in cases of nodular gynecomastia, as a screening for the contralateral breast in patients with newly diagnosed primary breast cancer instead of digital mammography of digital breast tomosynthesis, and in cases of suspicious nipple discharge without a correlate in conventional techniques.

Authorship1. Responsible for study integrity: J.A.S.

2 Study conception: J.A.S.

3. Study design: J.A.S.

4. Data acquisition: J.A.S., C.V.M.S., E.N.A.R., E.A.B., and R.A.S.

5. Data analysis and interpretation: J.A.S.

6. Statistical processing: J.A.S.

7. Literature search: J.A.S., S.M., and R.A.S.

8. Drafting of the manuscript: J.A.S., S.M., and R.A.S.

9. Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: J.A.S., S.M., and R.A.S.

FundingThis work has not received any type of funding.

Conflict of interestsNone.